Abstract

Background: Sacubitril/valsartan reduces cardiovascular death and hospitalizations for heart failure (HF). However, decision-makers need to determine whether its benefits are worth the additional costs, given the low-cost generic status of traditional standard of care.

Aims: To evaluate the cost-effectiveness of sacubitril/valsartan compared to enalapril in patients with HF and reduced ejection fraction, from the Singapore healthcare payer perspective.

Methods: A Markov model was developed to project clinical and economic outcomes of sacubitril/valsartan vs enalapril for 66-year-old patients with HF over 10 years. Key health states included New York Heart Association classes I–IV and deaths; patients in each state incurred a monthly risk of hospitalization for HF and cardiovascular death. Sacubitril/valsartan benefits were modeled by applying the hazard ratios (HRs) in PARADIGM-HF trial to baseline probabilities. Primary model outcomes were total and incremental costs and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) and the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for sacubitril/valsartan relative to enalapril

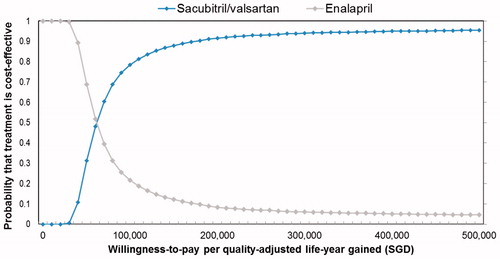

Results: Compared to enalapril, sacubitril/valsartan was associated with an ICER of SGD 74,592 (USD 55,198) per QALY gained. A major driver of cost-effectiveness was the cardiovascular mortality benefit of sacubitril/valsartan. The uncertainty of this treatment benefit in the Asian sub-group was tested in sensitivity analyses using a HR of 1 as an upper limit, where the ICERs ranged from SGD 41,019 (USD 30,354) to SGD 1,447,103 (USD 1,070,856) per QALY gained. Probabilistic sensitivity analyses showed the probability of sacubitril/valsartan being cost-effective was below 1%, 12%, and 71% at SGD 20,000, SGD 50,000, and SGD 100,000 per QALY gained, respectively.

Conclusions: At the current daily price sacubitril/valsartan may not represent good value for limited healthcare dollars compared to enalapril in reducing cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in HF in the Singapore healthcare setting. This study highlights the cost-benefit trade-off that healthcare professionals and patients face when considering therapy.

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a major public health problem worldwide with extensive burden of disease. Between 1–2% of the global population over 40 years of age have HF; this rises to 10% in those over 60–70 years old, and will continue to increase with an aging population. It is one of the major causes of hospital admissionsCitation1. After discharge, ∼ 25% have readmissions, and a further 5–10% die within 1 month. In Asia, data on HF burden is more limited; however, the available estimates are generally similar to that in the WestCitation2. Asian patients with HF have similarly poor or even worse outcomes than patients from the West, in part due to differences in clinical phenotypes and practice patternsCitation3.

Globally, the etiology of HF also varies, but hypertension and coronary artery disease (often associated with obesity and diabetes mellitus) appear to remain important, particularly so in Asia. Increase in these risk factors, related to changing lifestyles and ageing populations, is expected to drive higher burden of HF in AsiaCitation2. Despite so, Asians are often under-represented in global landmark trials of HF and, therefore, the generalizability of trial results to Asians remains uncertainCitation3. The latest PARADIGM-HF (Prospective Comparison of ARNI with ACEI to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure) trial is one of the largest and most globally representative trial in HF to date, with 18% (n = 1,487) of patients recruited in Asia. While the trial showed sacubitril/valsartan, a combination of an angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) and an angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB), reduced hospitalisations for HF and cardiovascular (CV) mortality by 20% compared with enalapril, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI), sub-group analysis by region showed the risk reduction for both endpoints were non-statistically significant in an Asian populationCitation4. Nonetheless, the study may be under-powered to detect sub-group-level effect; and statistical tests for interaction found no significant association between geographic region and the effect of treatment (p = .58)Citation5.

Based on evidence from PARADIGM-HF, sacubitril/valsartan has been recommended by international guidelines for HFCitation6. While management of Asian patients generally follow international practice, the uncertainty in clinical benefits of sacubitril/valsartan for Asian patients needs to be considered by payers, especially when it comes at a substantially higher upfront treatment cost compared to traditional standard of care (ACEIs) that are mostly generics. Recent cost-effectiveness studies for sacubitril/valsartan are all conducted from the US perspective, and that in the Asian healthcare setting is lackingCitation7–9. Therefore, we conducted a cost-effectiveness analysis, incorporating the treatment effects observed in the Asian sub-group of the PARADIGM-HF trial, in Singapore to assess the value for money of sacubitril/valsartan.

Methods

Model structure

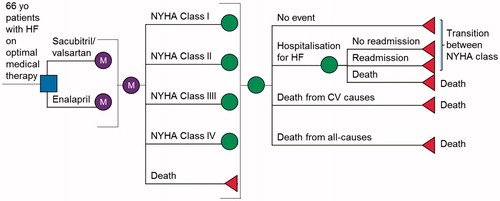

We developed a Markov model, which is a cohort-based state-transition model, to compare ARNI (sacubitril/valsartan) and ACEI (enalapril) for the prevention of hospitalizations for HF and CV mortality—the two primary endpoints of the PARADIGM-HF trial (). In line with the mean age of Singaporeans with HF, the starting age of the patient cohort was 66 yearsCitation2,Citation10,Citation11. Health states were New York Heart Association (NYHA) classes I–IV and deaths, with the majority of patients starting in classes II (72%) and III (24%), based on characteristics from PARADIGM-HF. Patients in each state incurred a monthly risk of hospitalization for HF and CV death. In addition, hospitalized HF patients were at risk of readmission for HF and in-patient deaths. While patients could experience only one readmission episode during the 1-month Markov cycle length, multiple readmissions over the time horizon were allowed to reflect clinical practice. We used a time horizon of 10 years, based on the average life expectancy of 5–10 years for patients with HFCitation12,Citation13. The analysis was conducted from Singapore healthcare payer’s perspective. All costs and health outcomes were discounted at 3% annually. Model development and analyses were performed using TreeAge Pro SuiteTM software 2016 (Williamstown, MA). shows the list of model inputs.

Figure 1. Markov model structure. Patients enter the model and are on either enalapril or sacubitril/valsartan. Patients who experience clinical events are transitioned through the health states of New York Heart Association function class I, II, III, IV, or death every month.

Table 1. Model inputs.

Data and sources

Clinical data

We estimated baseline probabilities of hospitalization for HF and CV death for the enalapril group by extrapolating published Kaplan-Meier curves from PARADIGM-HF trial using Weibull and exponential distributions, respectivelyCitation14. The clinical benefits of sacubitril/valsartan were modeled by applying the hazard ratios (HRs) to the baseline probabilities: it reduced hospitalizations for HF by 21% (HR = 0.79; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.71–0.89) and CV mortality by 20% (HR = 0.80; 95% CI = 0.71–0.89) relative to enalapril. Its treatment effect in the Asian sub-group was reflected using a HR of 1 as the upper limit in sensitivity analyses, given that the results were non-statistically significant in Asian patients: hospitalization for HF; 95% CI = 0.61–1.12 and CV mortality; 95% CI = 0.62–1.014. The treatment effect was assumed to continue beyond trial duration of 27 months over 10 years.

The probabilities of readmission for HF and in-patient deaths due to CV causes (defined as acute myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, HF, ischemic heart disease, peripheral artery disease, or stroke) within 1 month were derived from local epidemiological data (2015 data), and assumed to be the same across treatment groups. Background all-cause mortality was derived from 2016 life table data for a Singapore populationCitation15. These rates were adjusted as the cohort aged over the time horizon of the analysis. A two-fold increased risk of death, based on age-adjusted mortality ratios calculated from national case-mix data, was applied to the general all-cause mortality rates from the life tables to reflect the higher mortality burden due to HF. This risk was also assumed to be the same across treatment groups, and no treatment effect was modeled for this endpoint.

One-month transition probabilities between NYHA health states were derived from an established matrix in cost-effectiveness studies for HF ()Citation7. Patients could transition to a lower NYHA class, for example, from NYHA class II to class I, except post-hospitalizations or readmissions where they either remained within the same NYHA class or progressed, for example from NYHA class II to class III. These probabilities were fixed over time. Conservatively, the probabilities were assumed to be the same for both treatment groups, because it was unclear how sacubitril/valsartan altered the progression between health states relative to enalapril.

Table 2. NYHA transition probabilities per 1-month cycle.

Utility data

Utilities describe the quality-of-life for different NYHA classes according to individuals’ preferences and range from 1 (perfect health) to 0 (death). They are combined with life expectancy to generate quality-adjusted life years (QALYs). The utilities for NYHA classes were derived from the Care-HF (Cardiac Resynchronization in Heart Failure) trial, in which health-related quality-of-life was captured in patients with chronic HF and reduced LVEF (≤35%) on optimal medical therapy with the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions instrumentCitation16. Lower estimates for NYHA class IV (0.51) compared to class II (0.82) indicated poorer quality-of-life. A one-time disutility of 0.1 was applied, by subtracting patient’s utility in each NYHA class by 0.1, for each hospitalization or readmission eventCitation7,Citation17. Utilities were varied over their 95% CIs in sensitivity analyses.

Resource use and cost data

Only direct medical costs were used, in accordance with the model’s perspective. Medication costs were based on prices charged to patients at a tertiary national heart centre in Singapore for enalapril 10 mg twice daily (SGD 6.00/month) and sacubitril/valsartan 200 mg twice daily (SGD 270.00/month). These costs were varied widely (50% in each direction) in one-way sensitivity analyses to account for wide variations across different settings. The costs of additional HF medications and associated doctor visits were not considered; they were assumed to be equivalent between groups.

Costs of events were obtained from the national database with a case-mix of 6,663 patients with HF. The costs incurred during hospitalizations for HF of SGD 4,537 comprised doctor consultations, hospitalizations (average 5 days’ LOS), ICU stay (average 2–3 days’ LOS), procedures, investigations, and laboratory tests. The costs for readmissions for HF of SGD 4,317 were similar to the index hospitalization, given that clinical management is similar. The costs of in-patient deaths was higher, at SGD 7,170, because these patients required more intensive care and expensive treatment such as dialysis, on top of the costs of hospitalization.

Main outcome measures

The main outcome measures were the number of first hospitalizations for HF and CV deaths prevented, total and incremental costs and QALYs, and the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for sacubitril/valsartan relative to enalapril. The ICER is a ratio of incremental healthcare costs to incremental health outcomes or QALYs gained and expressed in terms of cost per QALY gained. It is typically compared against a cost-effectiveness threshold that reflects willingness-to-pay (WTP). In Singapore, there is no fixed WTP threshold to determine cost-effectiveness. To address this, sensitivity analyses were conducted for various WTP thresholds of between SGD 20,000 and SGD 100,000 per QALY gained.

Sensitivity analyses

We performed one-way sensitivity analyses and generated a Tornado diagram to present the relative impact of varying the model inputs on outcomes (i.e. ICERs). We conducted multivariate probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA), using 10,000 Monte Carlo simulations, to evaluate how the simultaneous uncertainties about model inputs across their distributions might influence outcomes.

Results

Base-case analysis

Among 1,000 66-year-old patients with HF treated with enalapril, our model predicted 306 hospitalizations for HF and 426 CV deaths over 10 years. Relative to enalapril, sacubitril/valsartan prevented an additional 37 hospitalizations for HF and 65 CV deaths (). The effectiveness of sacubitril/valsartan in reducing hospitalizations for HF and CV deaths translated into a mean gain of 0.21 QALYs per person. The total projected costs for enalapril and sacubitril/valsartan groups over the 10 years’ time horizon were SGD 2,197 and SGD 17,857, respectively. The additional mean cost of SGD 15,660 for treatment with sacubitril/valsartan was attributable to its substantially higher cost compared to enalapril (additional SGD 3,168 per surviving person annually, for 10 years), which was partially offset by fewer events in the sacubitril/valsartan group. These resulted in a base-case ICER for sacubitril/valsartan vs enalapril of SGD 74,592 (USD 55,198; based on SGD1 = USD0.74 as of September 2017) per QALY gained ().

Table 3. Projected clinical events per 1,000 patients with HF over 10 years’ modeled time horizon.

Table 4. Projected costs, benefits and incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

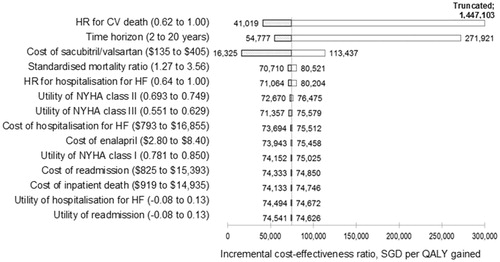

Sensitivity analysis

Deterministic sensitivity analysis showed that the effectiveness of sacubitril/valsartan in reducing the risk of CV death compared with enalapril was the key model driver. When the HR for CV death was varied across the 95% CI from 0.62–1.00—the upper limit reflecting the non-statistically significant treatment effect in the Asian sub-group—the ICER ranged from SGD 41,019 (USD 30,354) to SGD 1,447,103 (USD 1,070,856) per QALY gained. The modeled time horizon also had considerable impact; when the time horizon was shortened to the median follow-up duration of PARADIGM-HF trial (27 months), the cost per QALY increased to SGD 271,921 (USD 201,222). Conversely, modeling over a longer time horizon (20 years) resulted in an ICER of SGD 54,777 (USD 40,535). The cost of sacubitril/valsartan resulted in the third biggest impact on ICER, followed by background all-cause mortality rates and HR for hospitalization for HF. Other variables, including costs of events or quality-of-life values, had little impact on the cost-effectiveness of the treatment (<±SGD 3,000 in terms of cost per QALY) ().

Figure 2. One-way sensitivity analyses (Tornado diagram). The change in incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of sacubitril/valsartan vs enalapril associated with varying key model inputs are shown. The vertical line represents the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio in the base-case analysis. HF, heart failure; QALY, quality-adjusted life-year.

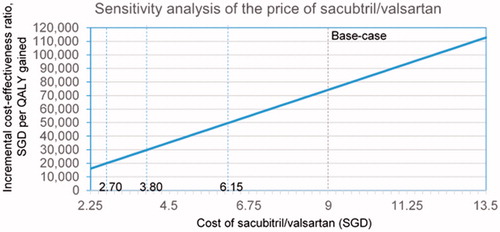

Additional analyses on cost of sacubitril/valsartan

Given the cost of sacubitril/valsartan—which can be variable depending on country and timing—was among the top three drivers of cost-effectiveness, we performed additional analyses to examine the impact of pricing on model results (). The daily cost of sacubitril/valsartan was set to SGD 9.00 in the base-case, based on current price. The price would need to drop by 70%, 58%, and 32% to SGD 2.70, SGD 3.80, and SGD 6.10, respectively, for sacubitril/valsartan to cost SGD 20,000, SGD 30,000, and SGD 50,000 per QALY gained.

Probabilistic sensitivity analyses

The average ICER per QALY gained from multivariate probabilistic sensitivity analyses, which took into account uncertainty of treatment effect in the Asian sub-group, was SGD 74,897 (USD 55,490). Out of 10,000 Monte Carlo simulations, sacubitril/valsartan were cost-effective below 1% of the time, at a WTP of SGD 20,000 or SGD 30,000 per QALY. This increased to 12% and 71% when WTP was increased to SGD 50,000 and SGD 100,000 per QALY gained, respectively ().

Figure 4. Probabilistic sensitivity analyses (cost-effectiveness acceptability curve). The curves show the proportion of the 10,000 model simulations at which sacubitril/valsartan was cost-effective across a range of thresholds. The analyses were performed by independently sampling each model input parameter from its distribution.

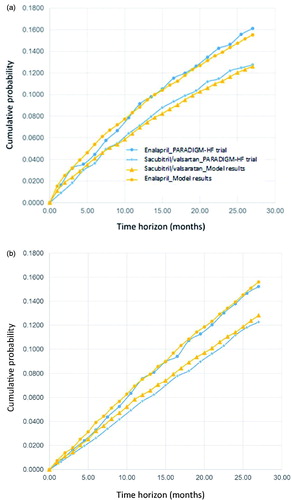

Model calibration

We calibrated the model by comparing the model simulation results to that observed in PARADIGM-HF for both hospitalizations for HF and CV mortality. Using micro-simulation with tracker variables, our model produced estimates of hospitalizations for HF and CV death that compared well with the rates observed in PARADIGM-HF (). These results suggest the model structure and baseline probabilities reflect current best estimates of the comparative effects of sacubitril/valsartan and enalapril on hospitalization for HF and CV death rates.

Discussion

As the final common pathway of a myriad of heart diseases, the burden of HF increases with the growing prevalence of CV disease. The World Health Organization has projected that the largest increases in CV disease worldwide are occurring in Asia. Sacubitril/valsartan offers an effective means to reduce the burden of HF. However, given the low-cost generic status of ACE inhibitors, decision-makers and payers need to determine whether the extra benefit with sacubitril/valsartan observed in PARADIGM-HF is worth the additional costs. This study is the first to examine the cost-effectiveness of sacubitril/valsartan vs enalapril, based on costs and resources used in Singapore, a developed country in Asia, to inform decision-making in healthcare.

Our study found that, relative to enalapril, sacubitril/valsartan prevented an additional 37 hospitalizations for HF and 65 CV deaths over 10 years. Sacubitril/valsartan costs payers SGD 74,592 (USD 55,198) per QALY gained compared with enalapril in the Singapore healthcare setting. Locally, the healthcare system is a combination of government healthcare subsidies, mandatory healthcare savings accounts, and health insurance. While there is no fixed WTP threshold, sacubitril/valsartan may not be considered cost-effective use of the finite healthcare budget, when benchmarking against other CV drugs in the Singapore healthcare setting with ICER of SGD 10,000 per QALY gainedCitation18. A price reduction of 32–70%, from the current price of SGD 9.00/day, will be needed for sacubitril/valsartan to cost between SGD 20,000 and SGD 50,000 per QALY gained and be considered cost-effective compared with other drugs in a similar therapeutic area. This will also improve the affordability for patients with HF who currently have no access to the drug due to cost barriers. Given the large and growing number of patients with HF, this will also ensure the sustainability of the healthcare system from a budgetary perspective.

The key model driver was the effectiveness of sacubitril/valsartan in reducing the risk of CV death that was assumed to last over the time horizon of 10 years. Of note, the uncertainty in its treatment effect in the Asian sub-group translated into an ICER of SGD 1,447,103 103 (USD 1,070,856) per QALY gained in sensitivity analyses. However, sub-group analyses are inherently under-powered. On the other hand, the effectiveness of sacubitril/valsartan in reducing the risk of hospitalizations for HF did not have a significant impact on the model. HF is a condition with significant mortality, so the modeled population declined over time due to increasing mortality. As a result, sacubitril/valsartan’s benefit for averting hospitalizations for HF diminished in the latter years. Correspondingly, the model simulated fewer hospitalizations for HF averted compared to CV deaths and was less sensitive to impact of hospitalization for HF. Accordingly, that the model did not incorporate endpoints such as reduction in emergency department readmissions for HF or ICU stays was unlikely to affect the cost-effectiveness results, given the relatively small impact of other benefits compared to CV death reductionCitation19.

These findings were consistent with recent cost-effectiveness analyses of sacubitril/valsartan conducted in the US setting. King et al.Citation7 found the cost-effectiveness of sacubtril/valsartan highly dependent on the duration of treatment effect, ranging from USD 249,411 per QALY at 3 years to USD 50,959 per QALY gained over a lifetime. Gaziano et al.Citation8 reported similar findings, with ICER of USD 135,964 per QALY gained when the benefit only lasting 27 months (trial duration) was modeled. Sandhu et al.Citation9 also reported ICER of USD 120,623 per QALY gained if the treatment was effective only for 27 months, with no subsequent reduction in event risks or improvement in quality-of-life, but continued costs. These analyses adopted a longer time horizon up to 30 years that inherently had greater uncertainty, given that the effectiveness results were extrapolated from a trial with a duration of 2 years. None of these analyses applied a treatment effect observed in the Asian population of PARADIGM-HF trial.

What set our work apart from these studies was contextualizing the cost-effectiveness analysis of sacubitril/valsartan in the local healthcare setting. Our modeled population reflected the average age of patients with HF in Singapore and incorporated the treatment effects using results from the Asian sub-group of PARADIGM-HF trial in sensitivity analyses. We used Singapore-specific all-cause mortality rates, with age-adjusted ratios derived from national epidemiological data to reflect higher mortality burden due to HF. Based on national epidemiological data, we applied 16% readmission rates for HF among hospitalized cases and 4% in-patient deaths due to CV causes within 1 month that were consistent with international figuresCitation20. We applied quality-of-life values for various NYHA classes; our utility inputs correlated well with the reported scores of 0.78 (SD = 0.18) to 0.51 (SD = 0.21) for mild-to-severe disease in patients with HF in a systematic review of utilities for CV diseaseCitation21. Local costs of hospitalizations and readmissions, however, were lower, at SGD 4,537 (USD 3,357) and SGD 4,317 (USD 3,195), respectively, compared to reported figures of USD 10,698 and USD 11,361 in the USCitation7. Such differences in costs of care in each country highlight the importance of conducting local cost-effectiveness analyses.

Our findings should be interpreted within the limitations of our analysis. First, we extrapolated the treatment benefits of sacubitril/valsartan for reducing hospitalizations for HF and CV mortality from PARADIGM-HF over 10 years. It remains to be known whether the assumption of sustained treatment effect of sacubitril/valsartan over enalapril beyond the trial and throughout the time horizon holds true. Second, the trial included an active run-in period so our results assumed that patients follow the recommended dose of each medication. Dose reduction is associated with higher risk for major CV eventsCitation22. In fact, local clinical experts have provided feedback about hypotensive episodes in real-life patients who are unable to tolerate sacubitril/valsartan’s hemodynamic effects at target dose, especially the older and frailer ones. This early clinical experience mirrored PARADIGM-HF trial data where sacubitril/valsartan was associated with significantly higher rates of hypotension than enalapril (17.6% vs 12.0%), but they rarely required discontinuation of treatment. Other common AEs such as hyperkalemia and renal impairment were not modeled. Given that the discontinuation of study medications due to these events was numerically lower among patients taking sacubitril/valsartan (10.7%) than among patients taking enalapril (12.3%) in PARADIGM-HF, the results from our analysis may be conservative. Furthermore, the analysis did not factor in the potential impact of chronic neprilysin inhibition with sacubitril/valsartan on the risk of developing dementia. Studies are currently ongoing to assess its effects on cognitive function.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study reports the long-term cost-effectiveness of sacubitril/valsartan vs enalapril for patients with HFrEF in the Singapore healthcare setting. Benchmarking against the ICERs of other drugs in the same setting, sacubitril/valsartan may not represent good value for limited healthcare dollars at its current price. This highlights the cost-benefit trade-off that healthcare professionals and patients face when considering HF therapy. Ultimately, the clinical decision on whether to use this novel agent should be individualized and based on shared decision-making that reflects treatment-related benefits, risks, costs, and patient preferences.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

No sponsorship/funding requires declaration.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

The authors have no financial relationships to declare. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work, but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Previous presentation

An abstract of the work was accepted for oral presentation at the HTAi 2017 Meeting in Rome, Italy.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Niti Matthew and Ms Mok Wei Ying for providing the national case-mix data.

References

- Ambrosy AP, Fonarow GC, Butler J, et al. The global health and economic burden of hospitalizations for heart failure: lessons learned from hospitalized heart failure registries. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:1123-33

- Reyes EB, Ha JW, Firdaus I, et al. Heart failure across Asia: same healthcare burden but differences in organization of care. Int J cardiol 2016;223:163-7

- Mentz RJ, Roessig L, Greenberg BH, et al. Heart failure clinical trials in East and Southeast Asia: understanding the importance and defining the next steps. JACC Heart Failure 2016;4:419-27

- Kristensen SL, Martinez F, Jhund PS, et al. Geographic variations in the PARADIGM-HF heart failure trial. Eur Heart J 2016;37:3167-3174

- McMurray JJV, Packer M, Desai AS, et al. Angiotensin–neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2014;371:993-1004

- Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2016 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update on new pharmacological therapy for heart failure: an update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:1476-1488

- King JB, Shah RU, Bress AP, et al. Cost-effectiveness of sacubitril-valsartan combination therapy compared with enalapril for the treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. JACC Heart Failure 2016;4:392-402

- Gaziano TA, Fonarow GC, Claggett B, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of sacubitril/valsartan vs enalapril in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. JAMA Cardiology 2016

- Sandhu AT, Ollendorf DA, Chapman RH, et al. Cost-effectiveness of sacubitril-valsartan in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Ann Intern Med 2015;163:401-8

- Lee R, Chan SP, Chan YH, et al. Impact of race on morbidity and mortality in patients with congestive heart failure: a study of the multiracial population in Singapore. Int J Cardiol 2009;134:422-5

- Leong KT, Goh PP, Chang BC, et al. Heart failure cohort in Singapore with defined criteria: clinical characteristics and prognosis in a multi-ethnic hospital-based cohort in Singapore. Sing Med J 2007;48:408-14

- Allen LA, Yager JE, Funk MJ, et al. Discordance between patient-predicted and model-predicted life expectancy among ambulatory patients with heart failure. JAMA 2008;299:2533-42

- Alter DA, Ko DT, Tu JV, et al. The average lifespan of patients discharged from hospital with heart failure. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:1171-9

- Hoyle MW, Henley W. Improved curve fits to summary survival data: application to economic evaluation of health technologies. BMC Med Res Method 2011;11:139

- Yearbook of Statistics Singapore. Population. Department of Statistics, Singapore; 2016. http://www.singstat.gov.sg/publications/publications_and_papers/reference/yearbook_of_stats.html

- Calvert MJ, Freemantle N, Cleland JG. The impact of chronic heart failure on health-related quality of life data acquired in the baseline phase of the CARE-HF study. Eur J Heart Failure 2005;7:243-51

- Yao G, Freemantle N, Flather M, et al. Long-term cost-effectiveness analysis of nebivolol compared with standard care in elderly patients with heart failure: an individual patient-based simulation model. PharmacoEconomics 2008;26:879-89

- Chin CT, Mellstrom C, Chua TS, et al. Lifetime cost-effectiveness analysis of ticagrelor in patients with acute coronary syndromes based on the PLATO trial: a Singapore healthcare perspective. Sing Med J 2013;54:169-75

- Packer M, McMurray JJ, Desai AS, et al. Angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibition compared with enalapril on the risk of clinical progression in surviving patients with heart failure. Circulation 2015;131:54-61

- Desai AS, Stevenson LW. Rehospitalization for heart failure. Predict or prevent? Circulation 2012;126:501-6

- Dyer MTD, Goldsmith KA, Sharples LS, et al. A review of health utilities using the EQ-5D in studies of cardiovascular disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010;8:13

- Vardeny O, Claggett B, Packer M, et al. Efficacy of sacubitril/valsartan vs enalapril at lower than target doses in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: the PARADIGM-HF trial. Eur J Heart Failure 2016;18:1228-34