Abstract

Aims: This study investigated annual medical costs using real-world data focusing on acute heart failure.

Methods: The data were retrospectively collected from six tertiary hospitals in South Korea. Overall, 330 patients who were hospitalized for acute heart failure between January 2011 and July 2012 were selected. Data were collected on their follow-up medical visits for 1 year, including medical costs incurred toward treatment. Those who died within the observational period or who had no records of follow-up visits were excluded. Annual per patient medical costs were estimated according to the type of medical services, and factors contributing to the costs using Gamma Generalized Linear Models (GLM) with log link were analyzed.

Results: On average, total annual medical costs for each patient were USD 6,199 (±9,675), with hospitalization accounting for 95% of the total expenses. Hospitalization cost USD 5,904 (±9,666) per patient. Those who are re-admitted have 88.5% higher medical expenditure than those who have not been re-admitted in 1 year, and patients using intensive care units have 19.6% higher expenditure than those who do not. When the number of hospital days increased by 1 day, medical expenses increased by 6.7%.

Limitations: Outpatient drug costs were not included. There is a possibility that medical expenses for AHF may have been under-estimated.

Conclusion: It was found that hospitalization resulted in substantial costs for treatment of heart failure in South Korea, especially in patients with an acute heart failure event. Prevention strategies and appropriate management programs that would reduce both frequency of hospitalization and length of stay for patients with the underlying risk of heart failure are needed.

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a disease that occurs mainly in elderly patientsCitation1–3. In North America and Europe, few patients with heart failure are 50 years of age or youngerCitation4 and more than 80% are 65 years of age or olderCitation5. The number of patients with heart failure is predicted to increase in countries with aging populationsCitation6. HF is also known to cause approximately 50% of re-hospitalizations within 6 months of discharge from the hospitalCitation7–10, and mortality in the hospital is about 10%Citation11–13. It is observed that 25% of patients who are hospitalized for heart failure die within a year, while 10% die within a monthCitation14.

Acute heart failure (AHF) is divided into acute decompensated heart failure, which shows one or more levels of worsened symptoms according to the New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification guidelines in patients who have already been diagnosed with heart failure, De Novo heart failure, which shows severe heart failure from the startCitation15,Citation16, and chronic heart failure or acute decompensated heart failure, which suddenly worsens from a state of declined contractility, and is mainly seen in real clinical settings. Symptoms of AHF are not to be considered as one-time events, but as worsened symptoms in patients with chronic heart failure that have manifested as AHF, and thus continued management of patients with heart failure must be considered.

The prevalence of heart failure in South Korea has increased by about 20% in 5 years from 99,708 patients in 2010 to 119,271 patients in 2014, and total medical expenses have increased by 38% during the same period from USD 50,914,022 to USD 71,231,260Citation17. The number of patients with HF has been increasing, with an average annual increase rate of 4.5% from 2009 to 2013. In the same period, the rate of increase in patients with heart failure over 80 years is 9%Citation17.

The proportion of population aged 65 years and over has increased from 7% in 1999 to 11.8% in 2012 and is expected to increase to 14% in 2017 and 20.8% in 2026Citation18. Although growth in the number of elderly people and changes in environmental factors are expected to increase the number of patients with heart failure and escalate medical costs to treat heart failure, use of medical services by patients with heart failure and the amount of direct medical expenses, which include out-of-pocket payments, are not yet identified in South Korea. In addition, criteria for diagnosing AHF must be accurate and used to find patients that meet such criteria, because the explicit criteria do not exist currently, and the treatment costs for AHF and heart failure must be confirmed by estimating the direct medical expenses of such patients. It is necessary to study the economic burden of heart failure, but it is impossible to classify acute heart failure using the claims data of the National Health Insurance. Therefore, we used medical records to diagnose acute heart failure and investigate the cost of 1 year of heart failure treatment. The aim of this study was to assess the costs of annual medical costs of patients for a year after being diagnosed with AHF, and examine the relationship between medical costs, medical utilizations, and comorbidities.

Patients and methods

Study criteria

A total of 330 patients, aged over 19 years, who were diagnosed with AHF at six tertiary university hospitals (Chonnam National University Hospital, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital, Severance Hospital and Wonju Severance Christian Hospital) from January 1, 2011, to June 30, 2012, were selected. After the diagnosis, these patients were hospitalized or used ambulatory services for the primary diagnosis of heart failure (or AHF) treatment for 1 year between 2011 and 2013. We collected data of the subjects by retrospectively reviewing their medical records. The study was conducted from September 2014 to October 2015.

In this study, patients with AHF are defined as subjects who were hospitalized or used emergency services at the time of AHF with congestion signs (edema, pleural effusion, or pulmonary edema) of NYHA class II or higher and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) > 100 pg/ml or N-terminal proBNP (NT-ProBNP) > 300 pg/ml. Patients excluded from the study were those who suffered from sepsis, liver disease, acute cardiovascular (CV) events (such as acute stroke, hemorrhage, or myocardial infarction) in the past 3 months; those who had organ transplants or were on the waiting list; those with heart failure due to chemotherapy; pregnant women; patients participating in interventional studies during the research period; and deceased patients. The reason for this is to identify only the costs for treatment of heart failure, as expenses for conditions such as stroke treatment or stent insertion cannot be considered direct medical expenses for heart failure.

Measurements

Diagnosis of accompanied diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, and anemia were investigated, as well as that of other CV diseases such as ischemic heart diseases, valvular heart disease, and atrial fibrillation. Also confirmed were the glomerular filtration rate (GFR), creatinine clearance (CrCl), hemoglobin (Hg), N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-ProBNP), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), and the pulse levels of the diagnostic time of AHF. Severe kidney dysfunction is common in patients with heart failure. Renal function is also known to be associated with the prognosis of heart failure. Renal function was assessed using the GFR and CrCl. NT-ProBNP and LVEF confirm the cardiac function. GFR can be measured by calculating the plasma clearance of various glomerular filtration markers like inulin, ethylene-diamine-tetra-acetic-acid, diethylene-triamine-penta-acetic acid (DTPA), iothalamate, and iohexolCitation19. Calculate CrCl from a timed urine collection (time, volume, and creatinine concentration), and plasma creatinine. NT-proBNP was measured in plasma by competitive enzyme immunosorbent assayCitation20. NT-proBNP is utilized in the diagnosis of heart failure as a marker indicating cardiac damage. LVEF, which is the amount of blood ejected during the left ventricular contraction, is a universal measure of the effectiveness of cardiac motion and is used as a key indicator of heart health. In addition, we confirmed the acute heart failure with NYHA class at the diagnostic point. The NYHA classification is commonly used as a functional indicator in patients with heart failureCitation4.

Medical costs

Direct medical costs were defined as costs incurred during hospitalization, or medical costs used for ambulatory services that the research subjects spent at the hospitals. All medical statements, including for non-reimbursement services for a year after the point of registration for each patient, were collected, and the expenses were calculated. The included items were costs for consultation, bed, meal, pharmaceuticals, treatment and procedure (including procedure and surgery, radiation therapy, materials, rehabilitation and physical therapy, psychotherapy, health check fees, and others), examination (examination, interpretation, computed tomography scan (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography scan (PET), and ultrasonic), and blood. Pharmaceutical cost is associated with oral and intravenous medications at the time of admission. However, pharmaceutical costs paid for dispensing in a pharmacy outside of the hospital were not included.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis was conducted to calculate the average medical costs for a patient with heart failure after an AHF event. The medical expenses and stay duration are shown as the mean and standard deviation (mean ± SD), median, and IQR (Inter Quartile Range). Patient-level healthcare cost data rarely meet assumptions of the ordinary least squares (OLS) regression. One of the characteristics of medical expenses data is that some of the people spend a lot of money. Therefore, the distribution of expense is often highly skewed to the right. Gamma Generalized Linear Models (GLM) with log link were used to analyze the factors affecting the treatment costs of heart failure. Independent variables included sex, age, comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and anemia), other CV diseases (ischemic heart diseases, valvular heart disease, and atrial fibrillation), and NYHA class at an AHF event. In previous studies, the length of stay, re-hospitalization, and the use of intensive care unit (ICU) were reported to be related to medical costsCitation21–25. Therefore, we considered these variables together. The length of stay was calculated only in the case when patients used emergency room services, ICUs, and wards. Statistical significance was identified at a significance level of 5%, and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for statistical analysis. All cost data were originally calculated in South Korean won (KRW) and presented in US dollars (USD; exchange rate: 1 USD = 1,185.2 KRW; December 31, 2012).

This study was conducted after receiving approval from the Institutional Review Boards of all the institutes that participated.

Results

Characteristics of patients

Among the total of 330 patients used as study subjects, there were 170 male patients (51.52%) and 160 female patients (48.48%), and the average age was 70.37 (± 13.68) years. The number of patients whose NYHA class was II at the time of diagnosis of AHF was 48 (14.55%), 165 patients were class III (50%), and 117 patients were class IV (35.45%). This shows that the percentage of patients whose NYHA class was III or above was high. A total of 198 patients had hypertension (60%), 97 had diabetes mellitus (29.39%), and 88 had anemia (26.76%). Among them, 81 had ischemic heart diseases (24.55%), 62 had valvular heart disease (18.79%), and 144 had arterial fibrillation (34.55%; ).

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients (n = 330).

At the time of acute heart failure diagnosis, the median LVEF of 330 patients was 37% (IQR = 28.00–51.60%), average NT-ProBNP was 1252.29 pg/mL (± 1154.38), average GFR was 94.60 (± 32.30) ml/min/1.73 m2, and the median CrCl was 77.10 ml/min (IQR = 53.75–101.85 ml/min).

Medical costs and service utilizations

Each patient spent an average of USD 4,300 (± 5,664) on AHF treatment, while the median value was USD 2,731. The average annual medical expense used by 330 patients from the point of diagnosis for treatment of heart failure (including AHF) was USD 6,199 (± 9,676). The average amount of money spent on hospitalizations for a year by each patient was USD 5,904 (± 9,666), and the median value was USD 3,101.

Taking into account the medical services for hospitalization used by 330 patients, the average number of hospitalizations during a year for each patient was 1.32 times (± 0.77). The average amount of money spent on each hospitalization was USD 4,462 (± 6,957), the median value was USD 2,598, and the average period of hospitalization for each time was 9.97 days (± 7.50). The average number of visits to ambulatory care was 5.87 (± 1.96) times a year, and the average amount of money used for outpatient services for a year was USD 282 per patient (± 205). Thus, each patient spent an average of USD 48 (± 70) for each visit to ambulatory care [].

Table 2. Per patient medical costs during 1-year follow-up.

There were 16 patients with a record of visiting the emergency room and being discharged from there during a year for treatment of heart failure. By checking details on the use of the emergency room, it was confirmed that the average cost for each visit was USD 508 (± 444), with the median value of USD 332, and the average annual emergency room expenses per patient were USD 603 (± 462), with the median value of USD 505.

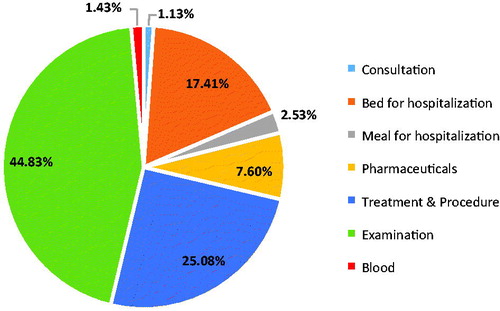

The results of the investigation of medical expenses used for each item for a year are given in . shows the proportion of each item is accounted hospitalization expenses. Treatment and procedure cost is an average of USD 1,482 per patient, and examination fees is USD 2,852. Examination cost accounts for the biggest portion of hospitalized costs, with USD 2,515 (44.83%), and treatment and procedure fees take up the next biggest portion, with USD 1,410 (25.08%).

Table 3. Composition of per patient medical costs during 1 year (USD).

Multivariate analysis for medical expenditure

shows the results of GLM with gamma distribution and log link function performed to determine the factors affecting heart failure treatment costs for 1 year.

Table 4. Results of generalized linear model with gamma distribution.

Those who are re-admitted have 88.5% higher medical expenditure than those who have not been re-admitted (p < .001) in 1 year, and patients using ICUs have 19.6% higher expenditure than those who do not (p < .001). When the number of hospital days increased by 1 day, medical expenses increased by 6.7% (p < .001). Those with ischemic heart diseases had 25.5% higher expenditure than those who did not (p < .001). The higher the NYHA class, the lower the medical costs (p < .001).

Discussion

According to the study results, a patient with AHF was hospitalized approximately 1.32 times a year, and most of the medical expenses spent during a year are for hospitalization, which accounts for more than 95% of the average annual medical expenses. The average number of hospital days was 9.95 days. The mean length of stay (LOS) of AHF patients was 8.3 days in the Czech RepublicCitation26, and other studies showed that medical expenses for hospitalization account for more than two-thirds of the total medical costs for 1 year for the treatment of heart failureCitation27–30.

In this study, we examined the factors affecting the medical cost of heart failure during the 1-year period from the time the patient suffered AHF. There was no significant association between age and medical costs for heart failure. No gender differences were identified in the analysis. While some studies reported a significant relationship between gender and older age with higher costsCitation31. Nationwide study from the Netherlands, age and gender were not significantly associated with treatment costsCitation32. Our results imply that the severity of the disease has a significant impact on healthcare costs.

When the patient was readmitted, the total medical expenditure increased. Further, using ICU, hospitalization periods were longer, total medical expenditure increased-> Using ICU and longer stay of hospitalization further increased medical expenditure. In other studies on cardiovascular disease, readmission is reported to have the greatest impact on the size of healthcare costsCitation21–25. In a Turkish study that identified factors affecting hospitalization costs for patients with angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, and heart failure, the cost of medical care for patients requiring the ICU was statistically significantCitation33. Large amounts of resources are consumed for hospitalization in an ICU. This study also confirmed that those with ischemic heart diseases had 25.5% higher expenditure than those who did not. Ischemic heart disease is the principal etiology of heart failure in the Western world. Ischemic heart disease confers a significantly worse prognosis in patients with left ventricular dysfunctionCitation34. Therefore, patients with heart failure who have ischemic heart disease can be considered to have a high degree of severity.

The higher the NYHA class, the lower the medical costs. There was no statistically significant difference in the medical expenses according to the NYHA class (p = .73). There might be two possible explanations. First, NYHA class is an indicator of the patient’s symptoms, and does not seem to determine treatment intensity. The second is the misclassification of the NYHA class. Raphael et al.Citation35 showed that the NYHA classification system is subjective and poorly reproducible. There is no widespread agreement on how to assign a patient to an NYHA class in clinical practice, with much inter-operator variation, and clinical trials rarely reference the criteria used. High-severity patients with HF will pay a lot of medical expenses.

Joshi et al.Citation36 state that length of stay in a hospital also increased with a higher Charlson’s comorbidity index (CCI) score. Such results show that inadequate chronic disease management will lead to longer periods of hospitalization. Thus, based on these results, there is a need for strategies to manage patients at high risk of a cardiovascular event, as well as patients with heart failure.

This study has some limitations. There is a possibility that medical expenses for AHF may have been under-estimated. The cost of outpatient prescription medicines was not included. Also, none of the 330 patients has an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) or cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) device inserted. These results indicate that the proportion of CRT/ICD procedures in Korea is not popular. Further studies are necessary concerning the proportion of devices in heart failure medical costs.

However, prices of prescription drugs for heart failure are not high in Korea. For example, the price of the renin-angiotensin drug is USD 0.44 per day, that of the mineralocorticoid drug is USD 0.04 per day, and that of the β-blocker is USD 0.35 per day. We considered the omission of the outpatient drug costs were minimal. Regarding the ICD and CRT, those procedures are not popular and there is strictly limited coverage within the National Health Insurance in South Korea.

In addition, there are constraints of representation because data from only six tertiary hospitals were used. Considering that most Korean patients with severe diseases tend to go to a large general hospitalCitation37, we collected all patients who met the criteria of AHF from the six tertiary hospitals distributed nationwide.

Conclusion

Medical expenses for hospitalization accounted for the majority of medical expenses for patients with heart failure for 1 year. The cost of treatment and examination accounted for about 50% of the annual medical expenses. The length of stays, ICU utilization, and re-admission were associated with an increase in medical expenses. Fundamentally, efforts for reducing CV diseases must come first, and appropriate strategies for management of patients who already have heart failure symptoms are needed. Such strategies must include reducing hospitalization and ambulatory care visits and improving the quality-of-life of patients.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Novartis Korea.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

The authors have no conflicts to declare. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

Approval of IRB: Graduate School of Public Health, Seoul National University, 1409/002-016; Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, B-1406/256-103; Seoul National University Hospital, H-1406-086-589; Wonju College of Medicine, Yonsei University, CR314013-002; Department of Internal Medicine, Yonsei University, 4-2014-0264; Cheonnam National University, CNUH-2014-151; The Catholic University of Korea Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital, KC14RSMI0413.

References

- Lakatta EG, Levy D. Arterial and cardiac aging: major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises part ii: the aging heart in health: links to heart disease. Circulation 2003;107:346-54

- Tsutsui H, Tsuchihashi-Makaya, M, Kinugawa, S, Goto, D, Takeshita, A. Clinical characteristics and outcome of hospitalized patients with heart failure in Japan. Rationale and design of Japanese Cardiac Registry of Heart Failure in Cardiology (JCARE-CARD). Circ J 2006;70:1617-23

- Iacoviello M, Antoncecchi V. Heart failure in elderly: progress in clinical evaluation and therapeutic approach. J Geriatr Cardiol 2013;10:165-77

- Holland R, Rechel B, Stepien K, et al. Patients’ self-assessed functional status in heart failure by New York Heart Association class: a prognostic predictor of hospitalizations, quality of life and death. J Card Fail 2010;16:150-6

- Bui AL, Horwich TB, Fonarow GC. Epidemiology and risk profile of heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol 2011;8:30-41

- Mosterd A, Hoes AW. Clinical epidemiology of heart failure. Heart 2007;93:1137-46

- Krumholz HM, Merrill AR, Schone EM, et al. Patterns of hospital performance in acute myocardial infarction and heart failure 30-day mortality and readmission. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2009;2:407-13

- Joynt KE, Jha AK. Who has higher readmission rates for heart failure, and why? Implications for efforts to improve care using financial incentives. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2011;4:53-9

- Chun S, Tu JV, Wijeysundera HC, et al. Lifetime analysis of hospitalizations and survival of patients newly-admitted with heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 2012;5:414-21

- Krumholz HM, Parent EM, Tu N, et al. Readmission after hospitalization for congestive heart failure among Medicare beneficiaries. Arch Intern Med 1997;157:99-104

- Abraham WT, Adams KF, Fonarow GC, et al. In-hospital mortality in patients with acute decompensated heart failure requiring intravenous vasoactive medications: an analysis from the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE). J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;46:57-64

- Haldeman GA, Croft JB, Giles WH, et al. Hospitalization of patients with heart failure: National Hospital Discharge Survey, 1985 to 1995. Am Heart J 1999;137:352-60

- Aranda JM Jr, Johnson JW, Conti JB. Current trends in heart failure readmission rates: analysis of Medicare data. Clin Cardiol 2009;32:47-52

- Harjola VP, Follath, F, Nieminen, MS, Brutsaert, D, Dickstein, K, Drexler, H, Hochadel, M, Komajda, M, Lopez-Sendon, JL, Ponikowski, P, Tavazzi, L, . Characteristics, outcomes, and predictors of 1-year mortality in patients hospitalized for acute heart failure. Eur Heart J 2006;27:3011-17

- Joseph SM, Cedars AM, Ewald GA, et al. Acute decompensated heart failure: contemporary medical management. Tex Heart Inst J 2009;36:510-20

- Hummel A, Empe K, Dörr M, et al. De novo acute heart failure and acutely decompensated chronic heart failure. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2015;112:298-310

- National Health Insurance Service. National Health Insurance statistical yearbook. Seoul, Korea: National Health Insurance Service; 2010–2014

- Statistics Korea. 2013. Population projections for Korea. Daejeon: Statistics Korea; 2013.

- Rahn KH, Heidenreich S, Bruckner D. How to assess glomerular function and damage in humans. J Hypertens 1999;17:309-17

- Magnusson M, Melander O, Israelsson B, et al. Elevated plasma levels of Nt-proBNP in patients with type 2 diabetes without overt cardiovascular disease. Diabetes Care 2004;27:1929-35

- Claesson L, Gosman-Hedström G, Johannesson M, et al. Resource utilization and costs of stroke unit care integrated in a care continuum: a 1-year controlled, prospective, randomized study in elderly patients: the Göteborg 70+ Stroke Study. Stroke 2000;31:2569-77

- Chang KC, Tseng MC. Costs of acute care of first-ever ischemic stroke in Taiwan. Stroke 2003;34:e219-21

- Diringer MN, Edwards DF, Mattson DT, et al. Predictors of acute hospital costs for treatment of ischemic stroke in an academic center. Stroke 1999;30:724-8

- Tu F, Tokunaga S, Deng Z, et al. Analysis of hospital charges for cerebral infarction stroke inpatients in Beijing, People’s Republic of China. Health Policy 2002;59:243-56

- Tu F, Anan M, Kiyohara Y, et al. Analysis of hospital charges for ischemic stroke in Fukuoka, Japan. Health Policy 2003;66:239-46

- Ondrackova B, Miklik, Roman, et al. In hospital costs of acute heart failure patients in the Czech Republic. Cent Eur J Med 2009;4:483-9

- Stewart S, Jenkins, A, Buchan, S, McGuire, A, Capewell, S, McMurray, JJ. The current cost of heart failure to the National Health Service in the UK. Eur J Heart Fail 2002;4:361-71

- Berry C, Murdoch DR, McMurray JJ. Economics of chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2001;3:283-91

- Neumann T, Biermann J, Erbel R, et al. Heart failure: the commonest reason for hospital admission in Germany: medical and economic perspectives. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2009;106:269-75

- Parissis J, Athanasakis K, Farmakis D, et al. Determinants of the direct cost of heart failure hospitalization in a public tertiary hospital. Int J Cardiol 2015;180:46-9

- Bramkamp M, Radovanovic D, Erne P, et al. Determinants of costs and the length of stay in acute coronary syndromes: a real life analysis of more than 10,000 patients. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2007;21:389-98

- Soekhlal RR, Burgers LT, Redekop WK, et al. Treatment costs of acute myocardial infarction in the Netherlands. Neth Heart J 2013;21:230-5

- Sözmen K, Pekel Ö, Yılmaz TS, et al. Determinants of inpatient costs of angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, and heart failure in a university hospital setting in Turkey. Anatol J Cardiol 2015;15:325-33

- Remme WJ. Overview of the relationship between ischemia and congestive heart failure. Clin Cardiol 2000;23(Suppl4):IV4-8

- Raphael C, Briscoe C, Davies J, et al. Limitations of the New York Heart Association functional classification system and self-reported walking distances in chronic heart failure. Heart 2007;93:476-82

- Joshi AV, D’Souza AO, Madhavan SS. Differences in hospital length-of-stay, charges, and mortality in congestive heart failure patients. Congest Heart Fail 2004;10:76-84

- Doo Ri K. The effect of having usual source of care on the choice among different types of medical facilities. Health Policy Manag 2016;26:195-206