Abstract

Aim: To elicit patients’ preferences for HIV/AIDS treatment characteristics in Colombia.

Materials and methods: A best–worst scaling case was used to provide a ranking of 26 HIV/AIDS treatment characteristics that were similar to a previous study conducted in Germany. In each choice task, participants were asked to choose the most important and the least important treatment characteristics from a set of five from the master list. Using the Hierarchical Bayes method, relative importance scores were calculated. Sub-group analyses were conducted according to sex, education, source of infection, symptoms, and age.

Results: A total of 195 patients fully completed the questionnaire. The three most important characteristics were “drug has very high efficacy” (relative importance score [RIS] = 10.1), “maximum prolongation of life expectancy” (RIS = 9.7), and “long duration of efficacy” (RIS = 7.4). Sub-group analysis showed only three significant (but minor) differences between older and younger people.

Conclusion: This study suggests that treatment characteristics regarding efficacy and prolongation of life are particularly important for patients in Colombia. Further investigation on how patients make trade-offs between these important characteristics and incorporating this information in clinical and policy decision-making would be needed to improve adherence with HIV/AIDS medication.

Introduction

The human immune deficiency virus (HIV) that causes acquired immune deficiency syndromeCitation1 continues to be a major global public health issue. Worldwide, there are currently ∼37 million people living with HIV/AIDS. In Colombia, ∼150,000 people are infected with HIVCitation1,Citation2, with incidence rates between 8–15 per 100,000Citation3. Anti-retroviral therapy can be used to prevent further progression of AIDS. However, adherence to anti-retroviral is sub-optimal, with adherence levels to HIV therapy reaching only 55% in North America and 77% in Sub-Saharan AfricaCitation4. Improving adherence is, therefore, urgently needed.

It is widely recognized that clinical and policy decisions should include the patient’s perspective. Eliciting patients’ preferences and incorporating preferences into clinical decision-making could lead to improved medication adherence, and can provide important insights for the development and appraisal of healthcare programs, alongside the clinical, economic, social, and ethical considerations.

Accordingly, stated preferences including discrete-choice experiments (DCE) and best–worst scaling (BWS) have been used increasingly to elicit preferences in healthcareCitation5–7. Several studies have already been conducted to elicit patient preferences for HIV/AIDS treatmentCitation8,Citation9. For example, the study of Terris-Prestholt et al.Citation10 suggested that people are more willing to use new prevention technologies to prevent HIV if their effectiveness is higher. Another study suggested that those living with HIV/AIDS prefer effective care and treatment over preventive programsCitation9. In addition, a DCE study conducted by Mühlbacher et al.Citation11, which assessed the importance of treatment characteristics, also used a rating scale; results suggested that effectiveness of medication, a low chance of side-effects, and the possibility of self-application of the drug are the most important characteristics for patients.

However, not much is known about the preferences regarding HIV/AIDS treatment of patients living with the infection in South America, since most research regarding patient preferences is conducted in western, developed countriesCitation5. It is also largely unknown to what extent the results of preference studies can be transferred to other countries or regions. Differences in socio-economic status, culture, cultural background, and population genetics could potentially affect patients’ preferences.

This study aimed to provide a ranking of patients’ preferred characteristics for treatment of HIV/AIDS in Bogotá, Colombia. As a first step to incorporate and assess the use of patients’ preferences into clinical and policy decision-making, it is important to assess which treatment characteristics are important for patients. The findings of our study could be included in a follow-up DCE, and would be interesting when making health policy decisions more consistent with the preferences of Colombian people living with HIV/AIDS and in helping physicians to improve adherence to therapy. In addition, this study could provide relevant information about the transferability of preference research from western developed countries to South American developing countries.

Methods

In this study, preferences were elicited using BWS. In BWS, developed by Finn and LouviereCitation12, participants need to select the most important and least important characteristic from a list of characteristics. BWS case 1 (also called BWS object case) was specifically used to assess the preferences of people living with HIV/AIDS regarding HIV/AIDS treatment. BWS case 1 provides the relative values associated with each of a list of objects, and allows the incorporation of a larger set of items or factors for eliciting preferencesCitation7.

List of factors and questionnaire

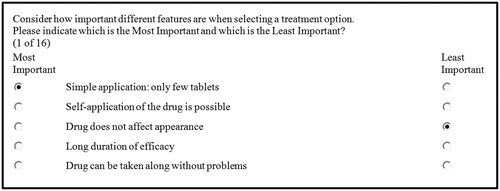

For this research, we used 26 AIDS treatment characteristics, similar to those used by Mühlbacher et al.Citation11. These characteristics were constructed by a qualitative research approach in Germany. In total, the questionnaire included 16 different BWS questions. In each BWS question, the respondent was asked to select the most important and least important treatment characteristics from a list of five attributes derived from the master list of 26 characteristics. A sample question is shown in . Four different versions of the BWS were developed to increase the efficiency of the experiment. Accordingly, the efficient design comprises 64 BWS questions that have been blocked into four groups. The choice sets were designed using Sawtooth Software’s SSI Web platform, resulting in fractional, efficient designs, which are characterized by orthogonality, minimal overlap, and positional balance.

The questionnaire consisted of the BWS survey and some socio-demographic questions and disease-related questions. The questionnaire was initially developed in English and translated into Spanish by a native speaker. The translation was validated by one additional Spanish native researcher. Furthermore, a focus group with five local patients was conducted to assess whether the questionnaire was clear enough for the patients and to assess if the 26 characteristics used corresponded to the experience and desires of local patients. Some minor changes in the wording were made after this pilot. At the end of the questionnaire, participants were asked to rate how difficult it was on a scale from 1 (very easy) to 7 (very difficult) and they were asked to provide any missing treatment characteristics; these were analyzed by one researcher (AH) and discussed with a second researcher (MH).

Participants and data collection

The study was conducted between April and May 2016 in Bogotá, Colombia. People living with HIV/AIDS were approached to participate in the study. Data collection was done at two HIV clinics, i.e. the Asistencia Cientifica de Alta Complejidad clinic and the Infecto Clinico, both located in Bogotá, Colombia. Both clinics are specialized, and treat only HIV patients, all corresponding complications, and sometimes comorbidity. Patients were approached by the researchers (AH or RvE) while waiting for their appointment. If a medical appointment interrupted the completion of the questionnaire, patients were instructed to continue after returning from their appointment. The researcher (AH or RvE) provided support and explanations where needed. This study was approved by the Asistencia Cientifica de Alta Complejidad’s scientific board and with written consent from the patients.

Analysis

Every questionnaire has 16 BWS questions and, thus, 32 possible answers (including 16 best answers and 16 worst answers). Questionnaires with more than five missing or incorrect entries or without demographic data were excluded from the analysis. Data was analyzed using the Hierarchical Bayes methodCitation7,Citation13 from Sawtooth Software’s SSI Web platform. The mean relative score of importance (RIS) was calculated for each of the 26 characteristics. Based on the raw coefficient of the preference function, rescaled scores were estimated which represent the relative importance of the factors. The RIS of all factors combined for each individual sum up to 100, in which a higher score indicates higher importance of the factor. The total of the relative importance scores always sums up to 100. If all aspects were to be equally important, the relative importance score for each item would be 3.84 (100/26). A score of 8 means a 2-fold higher importance than a score of 4. Fit statistic was used to identify inconsistent responders. We included only respondents with a fit statistic above 0.247, given that a fit statistic lower than 0.247 indicates purely random responses to the choice tasks (Sawtooth 2016). Another modeling approach (logit model) was also tested and provided similar results.

Sub-group analyses were done for gender (male vs female), education (higher education vs lower education); heterosexual source of infection vs homosexual source of infection vs other source of infection; older age vs younger age; and no symptoms vs symptoms. The median age (37 years) was used as the cut-off point for older and younger age. For each sub-group analysis, a one-way MANOVA was first conducted to see whether there was an overall difference between sub-groups in the RIS values of the 26 characteristics. When this was the case, one-way ANOVAs were conducted to see if the difference for each characteristic between the sub-groups was significant (0.05 was used as level).

Results

A total of 283 patients returned the questionnaire, of which 75 were excluded for the analysis because more than five entries were missing or incorrect, or the demographic data were lacking. Of the 205 completed questionnaires, eight were further excluded for having a fit-statistic score lower than 0.247, which suggests random and inconsistent responses (Sawtooth, 2016). These patients did not markedly differ from the included cases. A total of 195 cases were then included for the analysis. On average the task was seen as a relatively easy 3.14 on a scale from 1–7 (1 being easy, 7 being difficult). Approximately 50% of patients were interrupted in the completion of the survey by their appointment, and completed the survey afterwards.

The demographic characteristics of included respondents are described in . The majority of the participants were males (83%), and the main route of infection was sexual contact, of which 51% was through homosexual contact (100 out of 195) and 29% through heterosexual contact (57 out of 195). The mean age of the participants was 37.2 (SD = 11.2). Our population is similar to the overall HIV/AIDS population in Colombia, with most cases being aged between 35–39 years, and 72.83% of cases being maleCitation14.

Table 1. Patients’ characteristics.

Best–worst scaling

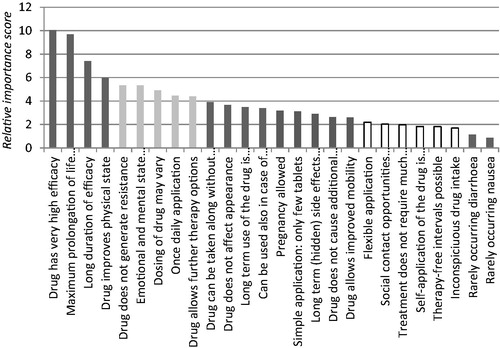

In , the results of the RIS per characteristic are shown, together with their 95% confidence interval. The most important characteristics were “drug has very high efficacy” (10.1), “maximum prolongation of life expectancy” (9.7), and “long duration of efficacy” (7.4). Statistically significant differences between importance scores are obtained with non-overlapping intervals.

Table 2. Group average relative importance score per HIV/AIDS treatment characteristic.

identified five groups of characteristics. Four characteristics regarding treatment efficacy/effects are included in the most important group. Five characteristics are insignificantly or close to insignificantly different from a score of 4.9. Nine features are insignificantly or close to insignificantly different from scores ranging from 2.9–3.4. Six features are insignificantly or close to insignificantly different from 1.9. All these three middle groups contain mixtures of outcome and convenience features. The last group contains two rare minor side-effects (“rarely occurring diarrhea” (1.2) and “rarely occurring nausea” (0.9)).

Sub-group analysis

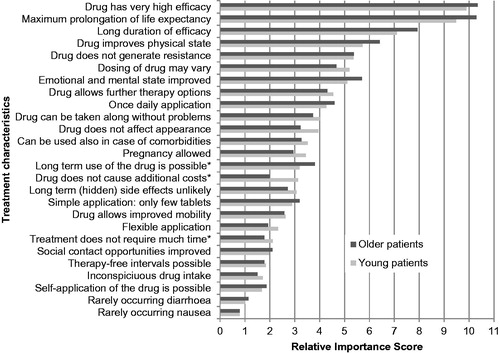

No significant differences in RIS were found for: male (156 cases) vs female (34 cases); higher education (96 cases) vs lower education (93 cases); heterosexual source (57 cases) of infection vs homosexual source of infection (100 cases) vs other source of infection (33 cases); and no symptoms (99) vs symptoms (79 cases). A significant difference was observed for younger vs elderly, with a Pillai’s trace of 0.014. Only three characteristics that were significantly different were associated with statistically significant differences in RIS, with two of them with a RIS change of less than 1.00. In comparison with the younger group, the older group has a larger RIS for “long-term use of the drug is possible”; this was perceived as more important by the older participants (see ), while the younger group had a higher RIS for “drug does not cause additional costs” and “treatment does not require much time” in comparison with the older group.

Additional treatment characteristics

Reading the comments participants left after filling in the questionnaire, 11 comments could be used to support the creation of seven new characteristics. These characteristics were: “less than daily intake of medication”; “medication does not cause sleep problems”; “medication protects newborns from mother to child transmission”; “it is possible to receive better treatment abroad”; “medication does not cause side effects on the skin”; “medication does not cause lipotrofia (degeneration of fat-tissue)”; and “personalized treatment is possible”.

Discussion

This study provides a ranking of treatment characteristics that are important for HIV/AIDS patients in Bogotá. It suggests that patients prefer treatments which have long and high efficacy and maximum increase of life expectancy. Next it was perceived important that treatment improves mental, emotional, and physical states. All these characteristics were more important than characteristics regarding the price, availability, usage, or side-effects of treatments. No substantial differences were found in sub-group analyses in terms of the overall ranking of RIS.

These findings are consistent with understanding of how patients in many other studies value medical technologies. The results of our study are similar overall to the study of Mühlbacher et al.Citation11, which used another approach to estimate the importance of the same 26 treatment characteristics in Germany. Only some differences that would not have a significant impact on intervention design or adherence were observed. The importance of “self-application of the drug is possible” and “long-term (hidden) side-effects unlikely” were considered as less important by the patients included in our study. However, improvement in mental and emotional state was more important in our study than in the German study. Possible explanations for these differences could be sought in cultural differences between Germany and Colombia, or in differences in study design, recruiting strategies, or elicitation methods. It should also be noted that the German study used the ranking only as a guide to designing a DCE.

The results of this study will be used in a follow-up DCE that will further elicit how HIV/AIDS patients make trade-offs between the most important treatment characteristics. BWS is an interesting methodology to determine which medication characteristics are important for inclusion in a DCECitation15. In addition, the results from this study could already be useful for health professionals and decision-makers, especially given the poor adherence to HIV/AIDS treatment. Having a clear idea of the patients’ expectations about their antiretroviral treatment is decisive for the clinician because their intervention is linked to that perception and must guarantee adherence based on that objective. It is the physician’s duty to educate the patient based on the actual facts. By knowing their preferences it is possible to create a link between them and the benefits offered by the treatment to improve adherence and final results. Accordingly, our study provides relevant information on the treatment characteristics that will need to be discussed during consultations with doctors.

In addition, although our study suggests no major differences in preferences between Colombian and Dutch patients, transferring preferences results between countries should be done with caution. Some differences in patients’/professionals’ preferences between countries have been reported elsewhereCitation16–18. Further international as well as methodological work on the transferability of preference data between countries would be needed.

When interpreting the results of this study, several limitations must be considered. First, we used treatment characteristics from another study. Even though a pilot study validated the characteristics for the context of Colombia, we cannot exclude that some characteristics could have been missed in the BWS questionnaire. So, some new characteristics have been added at the end of the questionnaire, in response to respondents’ input. Second, for comparability, the characteristics in the questionnaire were not explained very explicitly, in line with the previous German study. This could have confused the participants, e.g. “rarely occurring diarrhea” could be perceived as only once a month or only once a day. This could result in different preferences being given from patient to patient based on one’s perception and interpretation of a characteristic. Third, a limited number of participants were accompanied by friend or family, also when completing the questionnaire, which could have led to answers being more “socially desirable”. All the questionnaires were completed in the clinics and not at home. Participants might have experienced stress because of this, which could have affected results. Fourth, although a BWS case 1 offers the advantage of including a large list of treatment characteristics, the scale or intensity of the characteristics cannot be included. Further work including the intensity/level of characteristics will need to be done by means of a DCE for the most important treatment characteristics identified in this study. Perceived correlations among multiple features could also be possible, for example for high efficacy and life expectancy, and long duration of efficacy. Finally, we did not test differences in RIS on respondent rankings for patients who were interrupted by the consultation while completing the survey.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study suggests that, for HIV/AIDS patients in Colombia, treatment efficacy and prolongation of life are the most important treatment characteristics. This information could be important for policy decisions about HIV treatment and for helping clinicians in improving their patients’ adherence to therapy. In addition, our study suggests that, when compared with a similar study conducted in Germany, some differences were observed which could limit the transferability of preferences data between countries.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

No funding was used for this study.

Declaration of financial/other interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with regard to this study.

Acknowledgments

None.

References

- UNAIDS. UNAIDS Global report. UNAIDS; 2013

- WHO. People living with HIV (all ages). WHO; 2010

- Murray CJ, Ortblad KF, Guinovart C, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence and mortality for HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014;384:1005-70

- Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Buchan I, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa and North America: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2006;296:679-90

- Clark MD, Determann D, Petro S, et al. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: a review of the literature. PharmacoEconomics 2014;32:883-902

- Lancsar E, Louviere J. Conducting discrete choice experiments to inform healthcare decision making. PharmacoEconomics 2008;26:661-77

- Cheung KL, Wijnen BF, Hollin IL, et al. Using best–worst scaling to investigate preferences in health care. PharmacoEconomics 2016;34:1195-209

- Gazzard B, Ali S, Muhlbacher A, et al. Patient preferences for characteristics of antiretroviral therapies: results from 5 European countries. J Int AIDS Soc 2014 Nov 2;17(4 Suppl 3):19540

- Youngkong S, Baltussen R, Tantivess S, et al. Criteria for priority setting of HIV/AIDS interventions in Thailand: a discrete choice experiment. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:1

- Terris-Prestholt F, Hanson K, MacPhail C, et al. How much demand for new HIV prevention technologies can we really expect? Results from a discrete choice experiment in South Africa. PLoS One 2013;8:e83193

- Mühlbacher AC, Stoll M, Mahlich J, et al. Patient preferences for HIV/AIDS therapy – a discrete choice experiment. Health Econ Rev 2013 May 11;3(1):14

- Finn A, Louviere JJ. Determining the appropriate response to evidence of public concern: the case of food safety. J Public Policy Market 1992;11:12-25

- Muhlbacher AC, Zweifel P, Kaczynski A, et al. Experimental measurement of preferences in health care using best-worst scaling (BWS): theoretical and statistical issues. Health Econom Rev 2016;6:5

- Situación del VIH en Colombia 2015 – Cuenta de Alto Costo. http://cuentadealtocosto.org/site/images/Publicaciones/Situación%20del%20VIH%20en%20Colombia%202015.pdf

- Kremer IE, Evers SM, Jongen PJ, et al. Identification and prioritization of important attributes of disease-modifying drugs in decision making among patients with multiple sclerosis: a nominal group technique and best–worst scaling. PLoS One 2016;11:e0164862

- Hiligsmann M, Dellaert B, Dirksen C, et al. Patients’ preferences for anti-osteoporosis drug treatment: a cross-European discrete-choice experiment. Rheumatology 2017;56:1167-76

- Hifinger M, Hiligsmann M, Ramiro S, et al. Economic considerations and patients’ preferences affect treatment selection for rheumatoid arthritis patients: a discrete choice experiment among European rheumatologists. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:126-32

- Cheung KL, Evers SMAA, De Vries H, et al. Most important barriers and facilitators of HTA usage in decision-making in Europe. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2018 Jan 5:1-8. doi: 10.1080/14737167.2018.1421459. [Epub ahead of print]