Abstract

Aims: To describe healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) and costs among biologic-treated psoriasis patients in the US, overall and by disease severity.

Materials and methods: IQVIA PharMetrics Plus administrative claims data were linked with Modernizing Medicine Data Services Electronic Health Record data and used to select adult psoriasis patients between April 1, 2010 and December 31, 2014. Eligible patients were classified by disease severity (mild, moderate, severe) using a hierarchy of available clinical measures. One-year outcomes included all-cause and psoriasis-related outpatient, emergency department, inpatient, and pharmacy HCRU and costs.

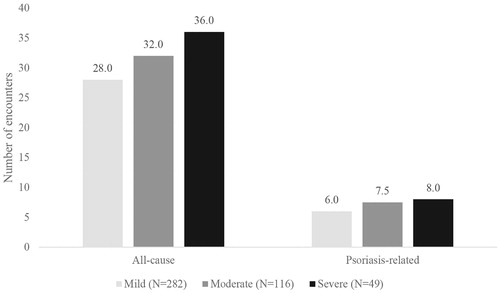

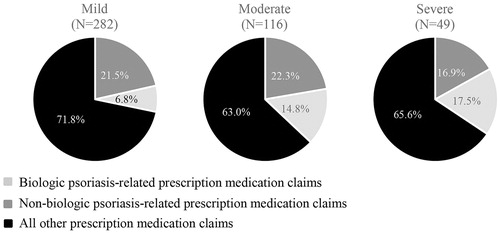

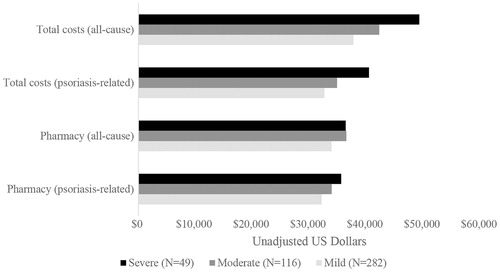

Results: This study identified 2,130 biologic-treated psoriasis patients: 282 (13%) had mild, 116 (5%) moderate, and 49 (2%) severe disease; 1,683 (79%) could not be classified. The mean age was 47.6 years; 45.4% were female. Relative to mild psoriasis patients, patients with moderate or severe disease had more median all-cause outpatient encounters (28.0 [mild] vs 32.0 [moderate], 36.0 [severe]), more median psoriasis-related outpatient encounters (6.0 [mild] vs 7.5 [moderate], 8.0 [severe]), and a higher proportion of overall claims for medications that were psoriasis-related (28% [mild] vs 37% [moderate], 34% [severe]). Relative to mild psoriasis patients, patients with moderate or severe disease had higher median all-cause total costs ($37.7k [mild] vs $42.3k [moderate], $49.3k [severe]), higher median psoriasis-related total costs ($32.7k [mild] vs $34.9k [moderate], $40.5k [severe]), higher median all-cause pharmacy costs ($33.9k [mild] vs $36.5k [moderate], $36.4k [severe]), and higher median psoriasis-related pharmacy costs ($32.2k [mild] vs $33.9k [moderate], $35.6k [severe]).

Limitations: The assessment of psoriasis disease severity may not have necessarily coincided with the timing of biologic use. The definition of disease severity prevented the assessment of temporality, and may have introduced selection bias.

Conclusions: Biologic-treated patients with moderate or severe psoriasis cost the healthcare system more than patients with mild psoriasis, primarily driven by higher pharmacy costs and more outpatient encounters.

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder, with the plaque type characterized by plaques that are usually painful, itchy, thick, red, and scalyCitation1,Citation2. Recent studies estimate that the age-adjusted prevalence of psoriasis among adults in the US is 3% (∼6.7 million adults), although estimates as low as 1% have been reportedCitation3,Citation4. Of all psoriasis patients, ∼18% have moderate-to-severe forms of the diseaseCitation3.

A variety of methods are used to assess psoriasis disease severityCitation5,Citation6. While the psoriasis area severity index (PASI) is the most commonly used method in clinical trials, it is typically not used in the clinical practice settingCitation5,Citation7. Other disease severity measures include body surface area (BSA), Physician’s Global Assessment (PGA), and Patient-Reported Global Assessment (PtGA)Citation6,Citation8. Disease severity, as determined by BSA, affected by psoriasis can be categorized into the following three groups: less than 3% is considered mild, 3–10% moderate, and more than 10% severeCitation9. PGA and PtGA, as assessed by a physician and patient, respectively, are used to measure plaque severity and have many variations, including 5-, 6-, or 7-point scales ranking plaques from “clear” to “severe”Citation8,Citation10.

The burden of psoriasis extends beyond skin manifestations to include associated comorbidities (most notably psoriatic arthritis found in up to 43% of psoriasis patientsCitation11,Citation12), decreased quality-of-life (QoL) and productivity, and increased cost of careCitation13–15. The burden of cardiovascular and related diseases, some malignancies, and other autoimmune conditions is particularly high among psoriasis patientsCitation13,Citation16–18. Psoriasis is also associated with depression and other mental health conditionsCitation19. Annual psoriasis direct costs in the US have been estimated to range from $52–$63 billion (2013 US dollars)Citation14, with moderate-to-severe patients accruing disproportionately high annual healthcare cost when compared to mild patients ($10,593 vs $5,011, respectively, using 2007 US dollars)Citation15.

The use of biologic therapies to treat moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis was first approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2003 and has resulted in improved treatment outcomes, higher clearance, acceptable safety profiles, and better health-related quality-of-lifeCitation2,Citation20,Citation21. However, the costs associated with biologic treatments are highCitation22,Citation23, and we have identified no publications of health care resource utilization (HCRU) and costs among biologic-treated psoriasis patients stratified by disease severity in the US. The objective of this study was to describe healthcare resource utilization and costs among psoriasis patients treated with biologics overall and by disease severity.

Methods

Study design

This was a retrospective study of adult psoriasis patients in the US using IQVIA PharMetrics Plus adjudicated medical and pharmacy claims data linked with Modernizing Medicine Data Services, Inc. (MMDS) Electronic Health Record (EHR) data. The study period was from January 1, 2010 to December 31, 2015. Patients were followed from first qualifying biologic prescription medication claim to the end of the 360-day follow-up period. This study was conducted using de-identified data, in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA).

Data sources

The IQVIA PharMetrics Plus database contains adjudicated claims for more than 130 million unique enrollees across the US, with both medical and pharmacy coverage since 2006, and with diverse representation of geography, payers, providers, and therapy areas. PharMetrics Plus was used to provide de-identified patient data on prescription medication use, medical history, healthcare resource utilization and costs, and patient age and sex.

The MMDS EHR contains encounter data from EHRs for more than 35 million patients in the US across eight medical specialties, including dermatology. As of the third quarter of 2017, more than 70 million visits to dermatologists have been recorded. Psoriasis patients were defined on a de-identified basis as those patients with a provider-recorded clinical diagnosis of psoriasis in the MMDS EHR. The MMDS EHR was also used to provide de-identified patient data on psoriasis disease severity and patient race/ethnicity.

These two databases were linked using a proprietary encryption algorithm and a deterministic matching algorithmCitation24,Citation25. Using a trusted third party, a patented encryption algorithmCitation26–28 that ensured compliance with HIPAA regulations was configured and deployed at MMDS to generate irreversible, hashed, and concatenated patient tokens. All identifiable EHR data remained at MMDS. At the trusted third party, the patient tokens then underwent a deterministic matching process to be assigned unique and persistent IQVIA patient IDs. The deterministic algorithm uses specific data points (e.g. first name, last name, sex, date of birth, street address, zip code) rather than statistical probability to ensure continuity of patient records across datasets. Once the IQVIA patient IDs were received from the trusted third party, patients with matching IQVIA patient IDs in both data sources were then assembled into a combined database.

Patient selection

Adult (≥18 years of age at any point during the calendar year of the index medication) psoriasis patients with ≥1 prescription medication claim for a biologic for the treatment of psoriasis were selected for study inclusion. The index medication was the first biologic prescription medication claim occurring on or after the date of the patient’s first MMDS EHR visit with continuous medical and pharmacy benefit eligibility in PharMetrics Plus throughout the baseline period (90 days prior to the claim date) and the follow-up period (360 days after the claim date). The index date was the date of the index medication claim. Patients with a single MMDS (or PharMetrics Plus) patient ID linking to multiple PharMetrics Plus (or MMDS) patient IDs and patients with data not meeting quality standards in PharMetrics Plus (e.g. missing year of birth or sex; payer type with high probability of incomplete claims information, suspect enrollment dates) were excluded.

Study measures

Patients were classified into disease severity cohorts based on their first recorded severity measure in the MMDS EHR during the follow-up period using a hierarchical methodology of available measures of PGA, BSA, or PtGA. Mild disease severity was defined as PGA 0–2; if no PGA available, BSA <3%; if no PGA and no BSA available, PtGA 0–2. Moderate disease severity was defined as PGA 3; if no PGA available, BSA 3–10%; if no PGA and no BSA available, PtGA 3. Severe disease severity was defined as PGA 4–5; if no PGA available, BSA >10%; if no PGA and no BSA available, PtGA 4–5. Prescription medications were identified using National Drug Codes (NDC) and the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS). Phototherapy was identified via HCPCS or the American Medical Association’s Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes.

The primary study outcomes included outpatient, emergency department (ED), inpatient, and pharmacy healthcare resource utilization and costs, which were reported from adjudicated medical and pharmacy claims. Outpatient healthcare resource utilization and costs included physician office visits, laboratory, radiology, surgical services, and ancillary/other outpatient services. Psoriasis-related healthcare resource utilization and costs were defined as any claim associated with a diagnosis or medication for psoriasis. Costs were presented overall and by costs to the payer and costs to the patient.

Patient demographics included age, sex, and race/ethnicity. Clinical characteristics were assessed during the 90-day baseline period prior to the index date and included body mass index (BMI), Charlson-Deyo Comorbidity Index (CCI) scoreCitation29, and top 10 comorbidities (recorded using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] codes at the 3-digit level).

Statistical analysis

All study variables, including baseline and outcomes measures, were analyzed descriptively using percentage distributions for categorical variables and descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation [SD], median, interquartile range [IQR], minimum, and maximum) for continuous and count variables. Unless otherwise specified, all patients were included in the descriptive statistics presented. SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) was used for constructing the analytic dataset and for statistical analyses.

Results

Sample selection and baseline characteristics

Of the 94,682 psoriasis patients present in the MMDS EHR database that linked to the PharMetrics Plus database, 49.5% (n = 46,859) had ≥1 claim during the study period. After applying the study inclusion and exclusion criteria, our final biologic-treated cohort consisted of 2,130 patients: 282 (13.2%) had mild, 116 (5.4%) moderate, and 49 (2.3%) severe psoriasis; 1,683 (79.0%) were unable to be classified. The average length of time from the index date to the date of the first recorded disease severity measurement during the follow-up period was 153.0 (SD =106.2) days for the overall biologic cohort, 161.7 (SD =99.6) days for biologic patients with mild psoriasis, 138.7 (SD =113.3) days for biologic patients with moderate psoriasis, and 137.2 (SD =121.4) days for biologic patients with severe psoriasis.

The mean age of the biologic cohort was 47.6 (SD = 11.7) years; 45.4% were female; and 73.7% were white. The average CCI score was 0.3 (SD =0.6). Of the biologic-treated cohort, 1.6% (n = 35) had ≥1 ICD-9/10 code for comorbid PsA during the study period (1.4%, n = 4 [mild], 2.6%, n = 3 [moderate], and 4.1%, n = 2 [severe]). The top five comorbidities recorded during the baseline period were essential hypertension (18.3%, n = 389), disorders of lipid metabolism (16.3%, n = 348), other and unspecified joint disorders (12.0%, n = 255), general symptoms such as fatigue or sleep disturbances (11.5%, n = 244), and other dermatoses (10.4%, n = 221). The top five comorbidities recorded during the follow-up period were essential hypertension (36.0%, n = 767), disorders of lipid metabolism (34.5%, n = 734), general symptoms such as fatigue or sleep disturbances (27.9%, n = 594), other and unspecified joint disorders (24.7%, n = 526), and respiratory system symptoms and other chest symptoms (24.5%, n = 521) (see for a full list of the top 10 comorbidities recorded during the baseline and follow-up periods).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics for the biologic cohort, overall and stratified by disease severity.

Outcomes

Healthcare resource utilization

Relative to patients who had mild psoriasis, patients with moderate or severe disease had more median all-cause outpatient encounters (28.0 [mild] vs 32.0 [moderate], 36.0 [severe]), more median psoriasis-related outpatient encounters (6.0 [mild] vs 7.5 [moderate], 8.0 [severe]), a higher proportion of overall claims for medications that were psoriasis-related (28.2% [mild] vs 37.0% [moderate], 34.4% [severe]), and a higher proportion of overall claims for non-biologic psoriasis medications (6.8% [mild] vs 14.8% [moderate], 17.5% [severe]). Relative to patients with severe psoriasis, patients with mild or moderate disease had a higher proportion of overall claims for biologic psoriasis medications (21.5% [mild], 22.3% [moderate] vs 16.9% [severe]) (; and ).

Figure 1. Median number of outpatient encounters (all-cause and psoriasis-related) during the follow-up period, stratified by disease severity.

Figure 2. Proportion of prescription medication claims that were psoriasis-related during the follow-up period, stratified by disease severity.

Table 2. Healthcare resource utilization during the follow-up period, overall and stratified by disease severity.

Healthcare costs

Considering overall costs (i.e. costs to the payer plus costs to the patient), relative to patients who had mild psoriasis, patients with moderate or severe disease had higher: median all-cause total costs ($37.7k [mild] vs $42.3k [moderate], $49.3k [severe]), median psoriasis-related total costs ($32.7k [mild] vs $34.9k [moderate], $40.5k [severe]), median all-cause pharmacy costs ($33.9k [mild] vs $36.5k [moderate], $36.4k [severe]), and median psoriasis-related pharmacy costs ($32.2k [mild] vs $33.9k [moderate], $35.6k [severe]) (; ). Costs to the payer were also substantially higher for patients with moderate or severe psoriasis relative to patients with mild disease ().

Figure 3. Median total and pharmacy costs (all-cause and psoriasis-related) during the follow-up period, stratified by disease severity.

Table 3. Healthcare resource costs during the follow-up period, overall and stratified by disease severity (payer and patient combined).

Table 4. Healthcare resource costs during the follow-up period, overall and stratified by disease severity (payer only).

When breaking out the overall costs by costs to the patient, relative to patients who had mild or moderate psoriasis, patients with severe disease had higher: median all-cause total costs ($2.1k [mild], $2.1k [moderate] vs $2.7k [severe]), median psoriasis-related total costs ($0.8k [mild], $0.9k [moderate] vs $1.2k [severe]), median all-cause pharmacy costs ($1.1k [mild], $0.9k [moderate] vs $1.3k [severe]), and median psoriasis-related pharmacy costs ($0.6k [mild], $0.6k [moderate] vs $0.7k [severe]) ().

Table 5. Healthcare resource costs during the follow-up period, overall and stratified by disease severity (patient only).

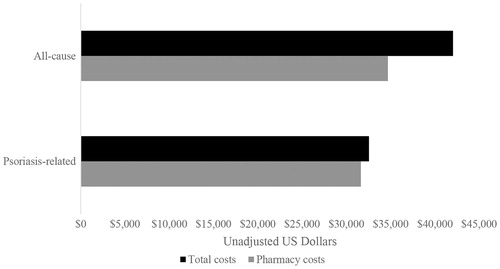

Looking at overall costs for the biologic-treated cohort, all-cause pharmacy costs represented 82.5% of all-cause total costs (84.5% [mild], 86.0% [moderate], and 73.9% [severe]) and psoriasis-related pharmacy costs represented 97.2% of psoriasis-related total costs (96.2% [mild], 96.3% [moderate], and 92.9% [severe]) (). While <50% of all-cause pharmacy claims were psoriasis-related (), 91.2% of all-cause pharmacy costs were psoriasis-related (92.5% [mild], 95.3% [moderate], and 90.4% [severe]). Psoriasis-related pharmacy costs represented 75.3% of all-cause total costs (78.1% [mild], 82.0% [moderate], and 66.8% [severe]). All-cause outpatient costs represented 12.1% of all-cause total costs (9.5% [mild], 9.2% [moderate], 10.7% [severe]), all-cause inpatient costs represented 4.8% of all-cause total costs (5.6% [mild], 3.6% [moderate], 14.7% [severe]), and all-cause ED visits represented 0.7% of all-cause total costs (0.4% [mild], 1.2% [moderate], 0.7% [severe]). Proportions similar to the ones presented above for the overall costs were seen when breaking out the overall costs by costs to the payer ().

Figure 4. Average total healthcare and pharmacy costs (all-cause and psoriasis-related) during the follow-up period (n = 2,130).

When breaking out the overall costs by costs to the patient, all-cause pharmacy costs represented 62.6% of all-cause total costs (70.8% [mild], 65.5% [moderate], 71.4% [severe]) and psoriasis-related pharmacy costs represented 91.5% of psoriasis-related total costs (90.6% [mild], 87.4% [moderate], 91.4% [severe]). Psoriasis-related pharmacy costs represented 80.0% of all-cause pharmacy costs (81.9% [mild], 84.5% [moderate], 85.4% [severe]) and 50.1% of all-cause total costs (58.0% [mild], 55.4% [moderate], 61.0% [severe] ().

Discussion

Using a large US administrative claims database linked with dermatology EHR data, this study assessed healthcare resource utilization and costs in a cohort of adult psoriasis patients being treated with biologics, overall and by disease severity. Our findings suggest that the economic burden of patients with moderate or severe psoriasis is higher relative to patients with mild disease. Our descriptive analyses revealed that, relative to patients who had mild psoriasis, patients with moderate or severe disease had more all-cause and psoriasis-related outpatient encounters, higher all-cause and psoriasis-related total costs, and higher all-cause and psoriasis-related pharmacy costs. Previous studies conducted in the US and Europe, using administrative claims, survey, or prospective observational data, have shown similar findings of increased healthcare resource utilization and costs with increased disease severityCitation15,Citation30–34. However, no prior studies have used both a direct measure of disease severity (i.e. defining disease severity based on clinical measures as opposed to a claims-based algorithm that assigns disease severity based on psoriasis therapies received) and adjudicated administrative claims; ours is the first contribution to the literature to do so.

Additionally, we found that pharmacy-related costs were the main driver of total costs (83%), specifically psoriasis-related pharmacy (75%), followed by costs associated with outpatient visits (12%). Notably, while inpatient stays represented only 5% of total costs in the overall biologic cohort, they represented 15% of total costs for patients with severe psoriasis. Pharmacy-related costs (63% and 84%) and outpatient visit costs (32% and 11%) were also the main drivers of total costs for patient and payer costs, respectively. These drivers of cost are slightly different than what has been reported previously. Major drivers of total healthcare costs in psoriasis patients were reported to be medical resource costs (71%)Citation15, outpatient services (44%)Citation30, and hospitalizations (30%)Citation33. Prescription drug costs were the primary driver of overall healthcare costs in one study in Spain (47%)Citation32, and were a minor driver in a study in Italy (18%)Citation33. These differences in findings could be due to the inclusion of patients who were only treated with non-biologic drugs and/or received no treatment for their psoriasis, differences in type of costs assessed, the operational definitions of costs that were used, and/or differences in the healthcare systems and healthcare costs in Spain and Italy as compared to the US. Al Sawah et al.Citation30 also found that total all-cause healthcare costs for psoriasis patients with moderate-to severe disease (as defined by use of any systemic therapy and/or phototherapy) were 2.5-times the total all-cause healthcare costs of those with mild disease, and that all-cause total healthcare costs for psoriasis patients treated with biologics were 3.2-times the total all-cause healthcare costs of those who did not receive biologics. These differences were primarily driven by outpatient pharmacy costs, which accounted for 52% and 63% of total all-cause costs among psoriasis patients with moderate-to-severe disease and among psoriasis patients treated with biologics, respectively.

There are several potential explanations for the increase in healthcare resource utilization and costs with increasing disease severity found in our study. For example, patients classified as having moderate or severe psoriasis may be more likely to need or seek medical attention due to the severity of the disease itself (as seen across other diseases). Alternatively, moderate or severe psoriasis patients may be more likely to experience an inadequate treatment response due to treatment failure or treatment intolerance, leading to increased healthcare resource utilization and costs. Finally, patients with moderate or severe psoriasis may have a greater number and/or severity of comorbidities, leading to increased healthcare resource utilization and costs. While it did not appear that the prevalence of comorbidities differed appreciably between the disease severity groups in our study, it is possible that some comorbidities, such as psoriatic arthritis, were not captured in the 90-day baseline period or 360-day follow-up period or that chronic conditions were not always recorded on an annual basis. Additionally, since ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes do not capture severity, it is possible that moderate or severe patients may have had more severe comorbidities, leading to increased healthcare resource utilization and/or costs. Feldman et al.Citation35 and Kimball et al.Citation36 found that psoriasis patients with comorbidities had higher healthcare resource utilization and costs than psoriasis patients without comorbidities, and Crown et al.Citation37 found that psoriasis patients with select comorbidities had higher total healthcare costs as compared to non-psoriasis patients with the same comorbidities. This suggests that comorbidities and psoriasis may be independent predictors of the increased healthcare resource utilization and costs observed among psoriasis patients with comorbidities. However, it is important to note that 75% of total costs consisted of psoriasis-related pharmacy costs, most likely driven by the relatively high cost of biologicsCitation22,Citation23, and the role that potentially uncaptured comorbidities played in regards to total costs was most likely small-to-moderate.

Finally, we note here that our study does not address the role that indirect costs plays on the economic burden of psoriasis, overall or by disease severity. Previous studies have shown that indirect costs have a significant impact on total healthcare costs, and that they also can increase with greater disease severityCitation32,Citation38. As a result, we have most likely under-estimated the true economic burden of psoriasis. However, the strength of our study lies in the ability to assign disease severity using EHR data as opposed to prescription claims for treatment received (or other claims-based algorithm) and report healthcare resource utilization and cost data based on adjudicated claims as opposed to surveys, which are subject to low-response rates, recall bias, and inaccurate reporting of healthcare resource utilization and costs due to patient perception.

Limitations

All retrospective database analyses are subject to certain limitations. For example, claims data are collected primarily for payment purposes and are subject to coding errors. Additionally, the data used for this study came from a primarily commercially insured population of patients, a large proportion of whom were less than 65 years old; therefore, the results of this analysis may not be applicable to other populations, such as patients who are uninsured, younger, or covered through Medicaid/Medicare.

Limitations of this analysis include that the study sample consisted of both biologic-experienced and biologic-naïve patients, that the assessment of psoriasis disease severity may not have necessarily coincided with the timing of biologic use, and that the recording of disease severity was performed on a voluntary basis by healthcare providers. Due to the sparseness of the data, disease severity was defined as the first available measure following the index date. This definition precluded our ability to assess temporality, and may have introduced selection bias, where severe patients could have selectively been non-responders of their biologic.

Additionally, there could have been differences between the disease severity groups that we were unable to capture and/or observe through the claims and EHR data, patient demographics and baseline clinical characteristics were not matched or controlled for between the disease severity groups, some of the disease severity groups were very small, no formal statistical tests were performed to compare strata of disease severity, and outliers were not removed. Psoriasis patients with comorbid psoriatic arthritis were not excluded from our study. These patients can have higher healthcare resource utilization and costs compared to psoriasis patients without comorbid psoriatic arthritisCitation30,Citation35. While less than 2% of our biologic-treated cohort had a diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis, it is possible that we did not capture all cases due to the limitations associated with claims data. This may have had an impact on our findings if there were a significant number of patients with uncaptured (or undiagnosed) psoriatic arthritis in our cohort, and if the proportion of psoriatic arthritis patients differed appreciably across the disease severity cohorts. Finally, we did not address costs associated with a decrease in quality-of-life or lost productivity; therefore, the full economic burden of psoriasis may be under-estimated.

Conclusions

In this study that included the unique linkage of adjudicated medical and pharmacy claims with EHR data, we found that biologic-treated patients with moderate or severe psoriasis appear to cost the healthcare system more than mild psoriasis patients. The cost was primarily driven by higher pharmacy costs and more outpatient encounters. This study highlights the importance of decreasing disease severity in order to potentially decrease the economic burden of psoriasis. For those patients on biologic therapy who remain with moderate-to-severe disease, newer biologic medications with different mechanisms of action and higher clearance levels have the potential to result in a greater proportion of patients with mild psoriasis and, thus, a potential reduction in the economic and clinical burden of psoriasis on the US healthcare system.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Eli Lilly and Company (Lilly). MJM, CKO, TMM, and ABA are employees of Lilly. AA, SAO, and DC are employees of IQVIA. JFM is an employee of Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

MJM, TMM, CKO, and ABA are employees and stock owners of Eli Lilly and Company. JFM is a consultant and/or investigator for Eli Lilly, Biogen IDEC, AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Incyte, Janssen, UCB, Samumed, Science 37, Celgene, Sanofi Regeneron, Merck, and GSK. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Previous presentations

AMCP Nexus 2017 abstract and poster.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Magdaliz Gorritz (IQVIA) for her contributions to the programming and data analysis.

References

- Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014;70:512–16

- Menter A, Gottlieb A, Feldman SR, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: Section 1. Overview of psoriasis and guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008;58:826–50

- Helmick CG, Lee-Han H, Hirsch SC, et al. Prevalence of psoriasis among adults in the U.S.: 2003–2006 and 2009–2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Am J Prev Med 2014;47:37–45

- Robinson D Jr, Hackett M, Wong J, et al. Co-occurrence and comorbidities in patients with immune-mediated inflammatory disorders: an exploration using US healthcare claims data, 2001–2002. Curr Med Res Opin 2006;22:989–1000

- Naldi L, Svensson A, Diepgen T, et al. Randomized clinical trials for psoriasis 1977–2000: the EDEN survey. J Invest Dermatol 2003;120:738–41

- Puzenat E, Bronsard V, Prey S, et al. What are the best outcome measures for assessing plaque psoriasis severity? A systematic review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010;24(Suppl 2):10–16

- Langley RG, Ellis CN. Evaluating psoriasis with Psoriasis Area and Severity Index, Psoriasis Global Assessment, and Lattice System Physician's Global Assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol 2004;51:563–9

- Griffiths CE, Vender R, Sofen H, et al. Effect of tofacitinib withdrawal and re-treatment on patient-reported outcomes: results from a Phase 3 study in patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017;31:323–32

- Horn EJ, Fox KM, Patel V, et al. Are patients with psoriasis undertreated? Results of National Psoriasis Foundation survey. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007;57:957–62

- Chow C, Simpson MJ, Luger TA, et al. Comparison of three methods for measuring psoriasis severity in clinical studies (Part 1 of 2): change during therapy in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index, Static Physician’s Global Assessment and Lattice System Physician’s Global Assessment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2015;29:1406–14

- Brockbank JE, Schentag C, Rosen C, et al. Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is common among patients with psoriasis and family medicine clinic attendees [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:S94

- Gladman DD, Antoni C, Mease P, et al. Psoriatic arthritis: epidemiology, clinical features, course, and outcome. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64(Suppl 2):ii14–17

- Helmick CG, Sacks JJ, Gelfand JM, et al. Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: a public health agenda. Am J Prev Med 2013;44:424–6

- Brezinski EA, Dhillon JS, Armstrong AW. Economic burden of psoriasis in the United States: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol 2015;151:651–8

- Yu AP, Tang J, Xie J, et al. Economic burden of psoriasis compared to the general population and stratified by disease severity. Curr Med Res Opin 2009;25:2429–38

- Sommer DM, Jenisch S, Suchan M, et al. Increased prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res 2006;298:321–8

- Gelfand JM, Gladman DD, Mease PJ, et al. Epidemiology of psoriatic arthritis in the population of the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005;53:573

- Kimball AB, Gladman D, Gelfand JM, et al. National Psoriasis Foundation clinical consensus on psoriasis comorbidities and recommendations for screening. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008;58:1031–42

- Schmitt J, Ford DE. Psoriasis is independently associated with psychiatric morbidity and adverse cardiovascular risk factors, but not with cardiovascular events in a population-based sample. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010;24:885–92

- Rich SJ, Bello-Quintero CE. Advancements in the treatment of psoriasis: role of biologic agents. J Manag Care Pharm 2004;10:318–25

- Wasilewska A, Winiarska M, Olszewska M, et al. Interleukin-17 inhibitors. A new era in treatment of psoriasis and other skin diseases. Postepy Dermatol Alergol 2016;33:247–52

- Feldman SR, Goffe B, Rice G, et al. The challenge of managing psoriasis: unmet medical needs and stakeholder perspectives. Am Health Drug Benefits 2016;9:504–13

- Shahwan KT, Kimball AB. Managing the dose escalation of biologics in an era of cost containment: the need for a rational strategy. Int J Womens Dermatol 2016;2:151–3

- Eichler GS, Cochin E, Han J, et al. Exploring concordance of patient-reported information on PatientsLikeMe and medical claims data at the patient level. J Med Internet Res 2016;18:e110

- Risson V, Ghodge B, Bonzani IC, et al. Linked patient-reported outcomes data from patients with multiple sclerosis recruited on an open internet platform to health care claims databases identifies a representative population for real-life data analysis in multiple sclerosis. J Med Internet Res 2016;18:e249

- Ober NS, Grubmuller J, Farrell M, et al. System and method for generating de-identified health care data. Google Patents; 2004

- Ober NS, Grubmuller J, Farrell M, et al. System and method for generating de-identified health care data. Google Patents; 2008

- Zubeldia K, Romney GW. Anonymously linking a plurality of data records. Google Patents; 2002

- Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 2005;43:1130–9

- Al Sawah S, Foster SA, Goldblum OM, et al. Healthcare costs in psoriasis and psoriasis sub-groups over time following psoriasis diagnosis. J Med Econ 2017;20:982–90

- Feldman SR, Fleischer AB Jr, Reboussin DM, et al. The economic impact of psoriasis increases with psoriasis severity. J Am Acad Dermatol 1997;37:564–9

- Carrascosa JM, Pujol R, Dauden E, et al. A prospective evaluation of the cost of psoriasis in Spain (EPIDERMA project: phase II). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2006;20:840–5

- Colombo G, Altomare G, Peris K, et al. Moderate and severe plaque psoriasis: cost-of-illness study in Italy. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2008;4:559–68

- Navarini AA, Laffitte E, Conrad C, et al. Estimation of cost-of-illness in patients with psoriasis in Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly 2010;140:85–91

- Feldman SR, Tian H, Gilloteau I, et al. Economic burden of comorbidities in psoriasis patients in the United States: results from a retrospective U.S. database. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:337

- Kimball AB, Guerin A, Tsaneva M, et al. Economic burden of comorbidities in patients with psoriasis is substantial. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2011;25:157–63

- Crown WH, Bresnahan BW, Orsini LS, et al. The burden of illness associated with psoriasis: cost of treatment with systemic therapy and phototherapy in the US. Curr Med Res Opin. 2004;20:1929–36

- Fowler JF, Duh MS, Rovba L, et al. The impact of psoriasis on health care costs and patient work loss. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008;59:772–80