Abstract

Aims: To assess the budget impact to a US commercial health plan of providing access to the Flexitouch (FLX) advanced pneumatic compression device (Tactile Medical) to lymphedema (LE) patients with either comorbid chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) or frequent infections.

Methods: Budget impact was calculated over 2 years for a hypothetical US payer with 10-million commercial members. Model inputs were derived from published sources and from a case-matched analysis of Blue Health Intelligence (BHI) claims data for the years 2012–2016. To calculate the budget impact, the Status Quo budget (i.e. total cost for LE and sequelae-related medical treatment) was compared to the budget under each of three Alternate Payer Policy scenarios which assumed that a sub-set of patients was redistributed from their initial treatment groups to a group that received FLX. Model outputs included cumulative payer costs, net budget impact, and breakeven point. Sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the impact of model inputs on results.

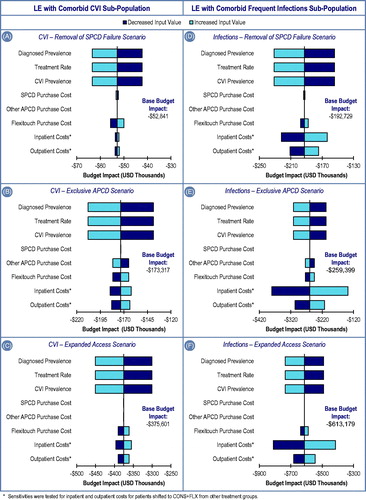

Results: Increasing access to FLX yielded a favorable budget impact in every scenario. For LE patients with comorbid CVI, the three alternate scenarios resulted in cumulative 2-year budget impacts of –$52,841, –$173,317, and –$375,601, respectively. For LE patients with comorbid frequent infections, the three alternate scenarios resulted in cumulative 2-year budget impacts of –$192,729, –$259,339, and –$613,179, respectively.

Limitations: Use of claims data assumes accurate coding and does not allow one to control for disease severity or treatment adherence. Also, the distribution of patients between treatment arms was determined using claims data from a specific payer organization, and could differ for health plans with different coverage policies.

Conclusions: While previous studies have illustrated cost savings with adoption of FLX, US commercial health plans may also achieve tangible cost savings by expanding access to FLX for LE patients with comorbid CVI and multiple infections.

Introduction

Lymphedema (LE) is a costly chronic condition caused by lymphatic dysfunction that results in a high protein edema, typically in an extremity. LE can occur as a result of congenital factors (primary), but it is more often a result of an alteration of normal lymphatic function (secondary), which in high-income countries is most commonly due to chronic venous insufficiency (CVI)Citation1 and cancer treatments involving lymph node removal or irradiationCitation2. LE is associated with both physical and psychosocial problems for patients. The swelling and subsequent fibrosis, resulting from accumulation of fluid in the dermal and subcutaneous tissues, can cause pain and disfigurement, and impair mobility and functionCitation3. LE produces a diminished immune response, which can result in painful and costly infectionsCitation4. Research into the costs of LE care to date has focused almost exclusively on cancer patients, most commonly post-breast cancer. These studies have demonstrated that medical costs for breast cancer patients who develop LE are 35–85% higher and over $20,000 greater than for those who do notCitation5,Citation6. There remains a dearth of information on the costs associated with treating non-cancer related LE.

The clinical literature suggests that certain sub-populations have increased risk of LE morbidityCitation7. Patients with phlebolymphedema, a vascular condition resulting from the combined effects of LE and chronic venous insufficiency (CVI), are known to be more difficult to manage than those with LE alone, due to the involvement of the two vascular systemsCitation8. These patients often experience significant edema, lipodermatosclerosis, and skin ulcerationCitation7. Infection, typically erysipelas, cellulitis, or lymphangitis, is also a common complication of LECitation9. Patients who experience one episode of cellulitis have a relatively high likelihood of recurrenceCitation10.

Although LE is a known cause of physical and psychosocial morbidity, treatment for chronic care patients can be challenging, and effective measures are seldom prescribedCitation3,Citation11,Citation12. In the absence of a permanent cure, LE patients must rely on long-term treatment strategies that improve symptoms and reduce complications. Initial conservative treatment of LE focuses on reduction of swelling. This phase of treatment may include manual lymphatic drainage (MLD), multilayer bandaging, compression garments, decongestive exercises, and/or elevation of the limb. For most patients, a subsequent maintenance phase of treatment is employed, usually in the home, which some studies suggest should include the use of a pneumatic compression device (PCD) to maintain edema reductionCitation13,Citation14. There are two types of PCDs commonly employed to treat LE: segmented PCDs without calibrated gradient pressure (also known as simple PCDs or SPCDs, HCPCS code E0651), and segmented PCDs with calibrated gradient pressure (also known as programmable multi-chamber PCDs, advanced PCDs, or APCDs, HCPCS code E0652). In the US, Medicare and most commercial payers restrict access to any type of PCD to patients with severe, chronic LE whose condition is not responsive to some or all of the initial conservative therapy treatments listed aboveCitation15–20. Private payers typically enforce further restrictions on APCDs, requiring providers to either identify unique patient characteristics that would preclude the use of an SPCD or to demonstrate failure to respond to treatment with such a deviceCitation15–20.

APCDs have been found to provide significant clinical benefit, including reduced edemaCitation9 and lower incidence of cellulitisCitation21. In addition, side-effects of PCD use are rareCitation22 and newer APCDs may reduce the risk of complications, such as genital edema, observed with older devicesCitation23. A specific APCD, Flexitouch (Tactile Medical), was chosen for evaluation in this study due to its robust efficacy dataCitation9,Citation21, including proof of its ability to stimulate the lymphatic system, which has not been proven for any other PCDsCitation14. The efficacy of Flexitouch has been hypothesized to be related to its design, which includes up to 32 inflatable chambers (compared to eight chambers with other APCDs) and 18 treatment program options, as well as its unique compression therapy profile, which closely simulates the optimally-performed MLD technique (compared to the higher pressure “squeeze-and-hold” technique employed by other devices)Citation24. In this study, we sought to evaluate the budget impact of treating specific LE patient populations with Flexitouch, instead of with other APCDs, SPCDs, or conservative therapy alone in a representative, privately insured US population.

Study design and methods

Model overview

An economic model was developed to evaluate the plan-level budget impact of shifts in patient distributions between LE treatment modalities under alternate US payer coverage policy scenarios. Outputs included cumulative costs, net budget impact, and breakeven point (i.e. the time required for payers to recoup PCD acquisition costs). The model calculated net budget impact annually for each of 5 consecutive years following the initiation of LE treatment, but cumulative results were reported at 2 years following treatment initiation to represent the usual time frame of interest to a commercial health plan. All costs and outputs were reported in US dollars. The model perspective is that of a hypothetical US insurer with 10 million commercial members.

Patient population

The model evaluated LE- and sequelae-related costs to the payer for patients with non-filarial LE and either comorbid chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) or frequent infections (≥2 per year), both of which represent sub-populations at risk for complications and attendant high medical costs. The modeled patient populations reflect the demographics and characteristics of patients from an analysis of subsequently case-matched LE patients in the Blue Health Intelligence (BHI) Research Database, a de-identified HIPAA-compliant commercial administrative claims dataset, which contains data on over 165 million covered lives in the US. Claims from this database were analyzed for the complete years 2012–2016. About 81,000 patients with non-filarial LE were initially defined as having one inpatient or two outpatient claims that included LE diagnosis codes. From that sample, 27,000 patients who were continuously enrolled with medical benefits for at least 12 months prior to and 6 months following LE diagnosis were included in the analysis.

The distribution of patients across LE treatment modalities was also derived from the BHI claims analysis. Specifically, among diagnosed and treated LE patients, 86.6% received conservative care (CONS), 1.7% received CONS + SPCD (HCPCS E0651), and 11.6% received CONS + APCD (HCPCS E0652, includes Flexitouch and other APCDs). We applied the same distribution of patients across treatment options to the CVI and 2+ infection sub-populations.

Additionally, and uniquely, the BHI dataset enabled reliable identification of claims for a specific APCD, Flexitouch (FLX, Tactile Medical). This was principally due to direct distribution of the device by the manufacturer and submission of claims linked to the company’s unique NPI number. In contrast, other APCDs are generally distributed through third-party durable medical equipment (DME) vendors, which typically sell devices from multiple manufacturers; those claims are, therefore, linked to the NPI of the DME provider. As a result, we were able to divide patients receiving an APCD (11.6%) into two mutually exclusive treatment groups. Among patients in the BHI dataset, 57% of those receiving an APCD received CONS + FLX and 43% received CONS + Other APCDs. The calculated distribution of patients across the four treatment groups in the Status Quo scenario is shown in .

Table 1. Status quo and alternate payer policy patient treatment distributionsTable Footnotea.

Modeled strategies

To evaluate the budget impact of payer adoption of FLX under various conditions, we modeled the impact of changes to current commercial coverage for FLX (Status Quo) on the proportion of patients likely to receive FLX. The study assumes that the Status Quo coverage policy requires failure of an SPCD prior to allowing access to APCDs, as is seen in many plansCitation15,Citation17,Citation18. We then designed three Alternate Payer Policy scenarios (): (1) SPCD Failure Removal Scenario; (2) Exclusive APCD Scenario; and (3) Expanded Access Scenario.

Table 2. Description of status quo and alternate payer policy scenarios.

We modeled Status Quo and Alternate Payer Policy patient distributions across treatment groups as follows: The SPCD Failure Removal Scenario shifted all patients from the CONS + SPCD treatment group in the Status Quo scenario to CONS + FLX in the Alternate Payer Policy scenario; the Exclusive APCD Scenario shifted all patients from the CONS + Other APCD treatment group in the Status Quo scenario to CONS + FLX in the Alternate Payer Policy scenario; and the Expanded Access Scenario shifted 10% of patients from the CONS treatment group in the Status Quo scenario to CONS + FLX in the Alternate Payer Policy scenario. Because it may be unlikely that a majority of conservatively managed patients would require maintenance therapy with a PCD, we selected 10% as a conservative estimate. The distributions of patients between treatment groups in each Alternate scenario (i.e. after shifts in treatment) are shown in .

Model inputs

The treatment rates and sub-population prevalence inputs for the model were obtained from the analysis of BHI claims (). Specifically, patients with at least one claim for active LE treatment (including manual lymphatic drainage, LE education, and/or LE-related physical therapy/occupational therapy [PT/OT]) were identified to determine a representative treatment rate for diagnosed patients. Within the treated population, we identified the diagnosed prevalence of comorbid CVI or two or more LE-related infections within 12 months of the index LE-related claim.

Table 3. Status quo inputs.

All cost inputs for the Status Quo scenario, including device acquisition and annual LE- and sequelae-related medical costs, are described in . Because device acquisition costs for commercial payers are not publicly available, we used Medicare reimbursement rates as a proxyCitation25. We also assumed that PCD costs were incurred by the payer, in full, at the start of year 1. This reflects the design of the claims analysis in which a PCD claim triggered the enumeration of subsequent costs, but it also reflects payer accounting for device purchases, in which costs are incurred up-front rather than amortized over the useful life of the device.

Per patient costs of medical care components for each treatment group were estimated from the analysis of BHI claims (). The claims analysis included costs associated with LE and relevant sequelae, as identified by a claim with a diagnosis code for primary or secondary LE, cellulitis, ulcers, septic shock, erysipelas, lymphangitis, or other local skin infection. Only costs following index treatment were included. Index treatment was defined for patients in the CONS treatment group as the first active LE treatment (e.g. compression garment, MLD, physical therapy) following the patient identification, and for patients in other treatment groups as receipt of a PCD following identification. These costs were then annualized, and mean costs were reported for each setting in which costs were incurred: i.e. inpatient, outpatient, emergency, physician office, home health, physical therapy, laboratory, and other service locations. Mean per patient per year costs were applied to all patients in the treatment group.

In the model, PCD costs were incurred as one-time costs at the beginning of year 1, but LE- and sequelae-related medical costs were calculated for the 12-month period following the initiation of treatment with conservative or PCD therapy. Because LE is a chronic condition, we assumed that medical costs would continue to be incurred beyond the first year. In the absence of information on the long-term cost consequences of LE, we assumed that medical costs remained constant for each subsequent year in the model.

Three case-matched cohorts were developed from the BHI claims dataset to control for differences in patient characteristics while evaluating the cost of treating patients with CONS + FLX vs each of the other three treatment modalities (CONS, CONS + SPCD, CONS + Other APCD). A stepwise propensity score matching approach was used to account for differences in clinical and demographic characteristics of the study cohorts. Cohorts were matched on Elixhauser comorbidity index components, age, gender, region of country, insurance type, and dummy indicators for the following clinical conditions: breast cancer, melanoma, uterine cancer, ovarian cancer, prostate cancer, cervical cancer, vaginal cancer, vulvar cancer, lymphoma, soft tissue sarcoma, congestive heart failure, CVI, venous leg ulcers, diabetes, iliac vein disorders, pulmonary hypertension, and postphlebitic syndrome. These case-matched comparisons were performed for both the CVI and recurrent infections sub-populations.

Status Quo scenario medical cost inputs for CONS, CONS + SPCD, and CONS + APCD treatment groups were estimated from these case-matched comparisons for each group vs CONS + FLX. Model inputs for annual costs in the Status Quo scenario are shown in and for each Alternate Payer Policy scenario in .

Table 4. Alternate payer policy medical cost inputs (mean per patient per year).

To estimate the medical cost inputs for the sub-set of patients shifted to the CONS + FLX treatment group in each Alternate Payer Policy scenario, we performed case-matched comparisons of costs for CONS + FLX patients vs the treatment group from which the patients originated. For example, in the SPCD Failure Removal scenario, a group of patients were shifted from the CONS + SPCD treatment group to the CONS + FLX treatment group. Costs for these patients were derived from the case-matched analysis of patients treated with CONS + SPCD vs CONS + FLX. Each Alternate Payer Policy scenario is independent and, therefore, no individual patient is affected by more than one scenario. This assumption of independence allows us to evaluate the additive effects when multiple Alternate Payer Policies are enacted simultaneously.

Sensitivity analysis

One-way sensitivity analyses were performed for each model input to evaluate the impact of each parameter on budget impact and on model conclusions. Specifically, we varied estimates for LE and sub-population prevalence, treatment distributions, and the largest patient medical cost input buckets (inpatient and outpatient costs), by ±20%. PCD costs were varied across the range of the SPCD and APCD Medicare reimbursement rates.

Results

CVI sub-population

Budget impact results are shown in . In the Status Quo scenario, the total cumulative 2-year cost for LE- and sequelae-related care for all phlebolymphedema patients covered by the hypothetical payer is $8,957,911. Over the same 2-year time frame, the Alternate Payer Policy SPCD Failure Removal, Exclusive APCD, and Expanded Access scenarios cost the plan $8,905,070, $8,784,594, and $8,582,310, respectively. The difference between the two states result in a 2-year budget impact of –$52,841, –$173,317, and –$375,601, respectively, or net cost-savings.

Table 5. Cumulative total 2-year budget impact.

In each of the three Alternate Payer Policy scenarios in which patients are granted access to FLX, the cost savings are realized primarily due to lower inpatient costs, with additional cost savings from lower outpatient costs. In the SPCD Failure Removal scenario, additional device acquisition costs for FLX are offset by healthcare cost savings at 0.71 years, while, in the Expanded Access scenario, breakeven occurs at 0.65 years.

Frequent infections sub-population

The total cumulative costs for LE and sequelae-related care incurred over 2 years by the hypothetical insurer for all patients within the sub-population of LE patients who contract two or more infections per year are $27,785,492 in the Status Quo scenario. Over the same 2-year time frame, the total cost of treating the same LE sub-population with frequent infections in the Alternate Payer Policy SPCD Failure Removal, Exclusive APCD, and Expanded Access scenarios was modeled to be $27,592,761, $27,526,091, and $27,172,311, respectively. The difference between the two states results in a 2-year budget impact of –$192,729, –$259,339, and –$613,179, respectively, or net cost-savings.

For the frequent infections population, cost-savings under the three policy scenarios are mostly due to lower inpatient costs. In the SPCD Failure Removal scenario, additional device acquisition costs for FLX are offset by healthcare cost savings at 0.41 years and in the Expanded Access scenario breakeven occurs at 0.67 years.

Sensitivity analysis

The results of the one-way sensitivity analyses demonstrate that the model was most influenced by diagnosed LE prevalence, treatment rate, and sub-population prevalence, followed by FLX acquisition costs. Because diagnosed LE prevalence, treatment rate, and sub-population prevalence are directly correlated with the size of the impacted population, the change in budget impact directly reflects the sensitivity multiplier. For instance, when each of these parameters is decreased by 20%, the budget impact is also decreased by 20%. Upward variation by 20% of FLX acquisition costs, inpatient costs, and outpatient costs result in less than a 6% increase in budget impact (i.e. reduction in cost savings). Despite variations in model input parameters, we found consistent cost savings across each Alternate Payer Policy scenario.

Discussion

Drawing on administrative claims data and other sources, we evaluated the 2-year budget impact of increased utilization of FLX by private US payers for specific LE sub-populations. Our model indicates that increasing access to FLX yielded a favorable budget impact in every modeled scenario. Thus, private health plans may achieve cost savings by granting or improving access to FLX for certain identifiable LE patient populations. Even though FLX adds one-time PCD acquisition costs of ∼$5,500 and ∼$4,500 for conservatively managed and SPCD patients (based on CMS reimbursement rates), respectively, net cost savings are achieved in less than 1 year due to lower costs of subsequent LE and sequelae-related medical care, primarily inpatient LE and sequelae-related expenditures. These findings cast doubt on the benefits of payer guidelines requiring both conservative therapy and documented failure of an SPCD prior to approving access to an APCD, specifically FLX, for patients in the studied sub-populations. While utilization of FLX following failure of an SPCD could not be evaluated in this study due to the small sample, other studies have demonstrated that early treatment reduces complications and halts progression of LECitation26,Citation27, suggesting effective treatment options should be employed as early as possible.

While several studies have evaluated the costs associated with LE treatment, to our knowledge this is the first study to model the costs of receiving different LE treatment options in case-matched cohorts. Existing literature has demonstrated the clinical and economic benefits of PCDsCitation28 and, specifically, FLXCitation21, most commonly in cancer patients. Brayton et al.Citation28 identified reductions in medical costs of ∼ $12,000 for cancer-related LE patients for the 12 months after receiving a PCD compared to the previous 12 months. By comparing the medical costs for patients on CONS () to the medical costs for patients shifted from CONs to CONS + FLX (), our study suggests that per-patient annual medical costs are reduced by > $8,000 for patients who undergo this payer policy shift, thus confirming the substantial savings achievable with PCD use. Similarly, drawing on a large administrative claims dataset, Karaca-Mandic et al.Citation21 found that costs declined for patients receiving FLX by 37% and 36% for cancer-related and non-cancer-related LE patients, respectively. Of note, the study designs differ substantially: while Brayton et al.Citation28 and Karaca-Mandic et al.Citation21 compare medical costs for the 12 months before and after initiation of PCD treatment, our study compared costs for case-matched cohorts treated with FLX vs other treatment modalities, including conservative treatment, SPCDs, and other APCDs.

Our results also demonstrate annual per patient medical cost savings for these other comparator arms, suggesting savings for patients shifted from CONS + SPCD to CONS + FLX ($6,336 and $11,000 for CVI and infections sub-populations, respectively) and from CONS + Other APCD to CONS + FLX ($4,549 and $4,001 for CVI and infections sub-populations, respectively). Lerman et al.Citation29 found similar results in patients with LE and comorbid CVI.

Finally, our study is the first to evaluate the budget impact of PCDs in LE patients with comorbid CVI or frequent infections from a US private payer perspective. Our model suggests that cost savings can be achieved in these sub-populations with greater use of FLX when compared to all other treatment modalities.

Our study has several limitations. First, the use of claims data assumes accurate coding and does not allow for detailed understanding of the exact clinical circumstances of LE treatment. Although treatment arms were case-matched, we were not able to determine the LE severity through claims. Second, while it is not possible to determine the level of adherence to therapy based on claims (i.e. a claim for receipt of a PCD does not guarantee prescribed use), the data as analyzed reflect costs observed in real-world management of LE. Third, the distribution of patients between treatment arms in this study was determined using claims from the BHI database, comprised of members of Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association (BCBS) health plans. This distribution may differ for other health plans, particularly as some BCBS plans have less restrictive coverage policies regarding APCDsCitation16,Citation19 than other known policiesCitation15,Citation17,Citation18,Citation20. Fourth, pharmaceutical costs for LE patients were excluded from the model. Pharmaceutical costs are likely to be covered by a patient’s pharmacy benefit, while the costs included in our model are medical and DME costs most likely to be covered within the plan’s medical benefit. As further support for the exclusion of pharmaceutical costs, Brayton et al.Citation28 also found that pharmaceutical costs related to LE care were negligible for both patients treated with PCDs and those not treated with PCDs. Finally, while there is known to be significant under-diagnosis and under-treatment of LECitation30,Citation31, it is unclear in which direction improved diagnosis of LE would impact our model results.

Despite these limitations, our study provides clear evidence of cost savings achieved through increased utilization of FLX in specific lymphedema populations. We recognize that models such as this one are only a representation of reality and that payers may not shift all patients at once to FLX. For example, it may be the case that, under some plans, when a step edit is removed, patients may get a variety of APCDs. However, our objective was to estimate the budget impact of moving specific LE sub-populations to FLX, and, because medical cost savings outweigh additional device costs for these patients, shifting an even greater share of patients to FLX over time should generate even greater cost savings. The observed lower LE and sequelae-related medical costs may also under-estimate the true impact of shifting patients to FLX, as unrelated healthcare costs as well as non-healthcare costs may be reduced with improvement in overall health.

Conclusion

This analysis provides important insights for individuals involved in the development of medical policies for private US payers. The primary finding of this study, that near-term cost savings can be achieved by shifting specific LE sub-populations to FLX, calls into question current US payer coverage policies that restrict access to PCDs in general, and to FLX specifically. The clinical benefits of FLX, including reduction in episodes of cellulitisCitation21, reduced limb volume and edemaCitation9,Citation13,Citation14, and improvement in skin fibrosis and functionCitation9,Citation13,Citation14, have been demonstrated in several publications, but, until now, the budget impact and return on investment has remained uncertain. Our results suggest that US health plans may achieve near-term cost savings by removing existing requirements for failure of SPCDs and other restrictions to FLX and instead granting faster access to FLX for the identified LE patient populations.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was sponsored by Tactile Medical (Minneapolis, MN), the company that manufactures the Flexitouch pneumatic compression device for the treatment of lymphedema.

Declaration of financial/other interests

TO is a consultant to Tactile Medical, a company that manufactures a product to treat lymphedema, where he serves as Chief Medical Officer. He holds stock options as part of the compensation plan. AMC, JAG, JI, and LG received consultative reimbursement from Tactile Medical for their independent performance of the analysis. TN received consultative reimbursement from Health Advances for his independent performance of the statistical analysis. No other disclosures are reported. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

No assistance in the preparation of this article is to be declared.

Data availability statement

The claims data that support the findings of this study are available via purchase from Blue Health Intelligence. The methodology section contains description of the specific claims data utilized. Medicare fee schedule data is openly available from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services at https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/DMEPOSFeeSched/DMEPOS-Fee-Schedule-Items/DME17-D.html.

References

- Dean S, editor Differential diagnosis of lower limb edema. The American College of Phlebology 30th Annual Congress; 2016. Available from https://lymphaticnetwork.org/symposium-series/differential-diagnosis-of-lower-limb-edema [Accessed: 8 January 2018]

- Douglass J, Graves P, Gordon S. Self-care for management of secondary lymphedema: a systematic review. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2016;10(6):e0004740. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004740.

- Warren AG, Brorson H, Borud LJ, et al. Lymphedema: a comprehensive review. Ann Plast Surg. 2007;59:464-72.

- Preston N, Seers K, Mortimer P. Physical therapies for reducing and controlling lymphoedema of the limbs. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;18:Cd003141.

- Shih YC, Xu Y, Cormier JN, et al. Incidence, treatment costs, and complications of lymphedema after breast cancer among women of working age: a 2-year follow-up study. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:2007–14.

- Basta MN, Fox JP, Kanchwala SK, et al. Complicated breast cancer-related lymphedema: evaluating health care resource utilization and associated costs of management. Am J Surg 2016;211:133-41.

- The diagnosis and treatment of peripheral lymphedema: 2013 Consensus Document of the International Society of Lymphology. Lymphology 2013;46:1-11.

- Lee BB, Andrade M, Antignani PL, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of primary lymphedema. Consensus document of the International Union of Phlebology (IUP)-2013. Int Angiol 2013; 32(6): 541-74.

- Fife CE, Davey S, Maus EA, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing two types of pneumatic compression for breast cancer-related lymphedema treatment in the home. Support Care Cancer 2012;20:3279-86.

- Oh CC, Ko HC, Lee HY, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for preventing recurrent cellulitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infection 2014;69:26-34.

- Fu MR, Ridner SH, Hu SH, et al. Psychosocial impact of lymphedema: a systematic review of literature from 2004 to 2011. Psycho-oncology 2013;22:1466-84.

- Ridner SH. The psycho-social impact of lymphedema. Lymphat Res Biol 2009;7:109-12

- Muluk SC, Hirsch AT, Taffe EC. Pneumatic compression device treatment of lower extremity lymphedema elicits improved limb volume and patient-reported outcomes. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2013;46:480-7.

- Adams KE, Rasmussen JC, Darne C, et al. Direct evidence of lymphatic function improvement after advanced pneumatic compression device treatment of lymphedema. Biomed Optics Express 2010;1:114-25.

- Aetna. Lymphedema medical clinical policy bulletin: Policy number 0069. August 25, 2017. Available from http://www.aetna.com/cpb/medical/data/1_99/0069.html [Accessed: 20 December 2017]

- BlueCross BlueShield of North Carolina. Pneumatic compression pumps for treatment of lymphedema and venous ulcers. Corporate Medical Policy. May 2017. Available from https://www.bluecrossnc.com/sites/default/files/document/attachment/services/public/pdfs/medicalpolicy/pneumatic_compression_pumps_for_lymphedema_and_venous_ulcers.pdf [Accessed: 20 December 2017]

- Cigna. Pneumatic compression devices in the home setting. Medical coverage policy number 0363. February 13, 2013. Available from Website: https://www.cigna.com/assets/docs/health-care-professionals/future_coverage_positions/mm_0363_coveragepositioncriteria_pneumatic_compression_devices.pdf [Accessed: 8 January 2018]

- Humana. Pneumatic compression pumps. Medical coverage policy: Policy number HGO-0478-012. May 25, 2017. Available from http://apps.humana.com/tad/tad_new/Search.aspx?criteria=pneumatic+compression+pumps&searchtype=freetext&policyType=both [Accessed: 8 January 2018]

- Massachusetts BCBSo. Pneumatic compression pumps for treatment of lymphedema and venous ulcers. Medical policy: Policy number 354. January 1, 2017. Available from https://www.bluecrossma.com/common/en_US/medical_policies/354%20Pneumatic%20Compression%20Pumps%20for%20Treatment%20of%20Lymphedema%20and%20Venous%20Ulcers%20prn.pdf [Accessed: 20 December 2017]

- Anthem. Pneumatic compression devices for lymphedema cverage guideline: Guideline number CG-DME-06. December 27, 2017. Available from https://www.anthem.com/medicalpolicies/guidelines/gl_pw_a053537.htm [Accessed: 20 December 2017]

- Karaca-Mandic P, Hirsch AT, Rockson SG, et al. The cutaneous, net clinical, and health economic benefits of advanced pneumatic compression devices in patients with lymphedema. JAMA Dermatol 2015;151:1187-93.

- Zaleska M, Olszewski WL, Durlik M. The effectiveness of intermittent pneumatic compression in long-term therapy of lymphedema of lower limbs. Lymphat Res Biol 2014;12:103-9.

- Cannon S. Pneumatic compression devices for in-home management of lymphedema: two case reports. Cases J 2009;2:6625. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-2-6625.

- Mayrovitz HN. Interface pressures produced by two different types of lymphedema therapy devices. Phys Ther 2007;87:1379-88.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 2017 Durable medical equipment, prosthetics/orthotics, and supplies fee schedule. CMMS; 2017

- Kilgore L, editor. Reducing breast cancer related lymphedema (BCRL) through prospective surveillance monitoring using bioimpedance spectroscopy (BIS) and patient directed self-interventions. Orlando, FL: American Society of Breast Surgeons; 2018

- Moffatt CJ, Franks PJ, Doherty DC, et al. Lymphoedema: an underestimated health problem. QJM : monthly journal of the Association of Physicians. 2003 Oct;96(10):731-8. PubMed PMID: 14500859; eng.

- Williams AF, Franks PJ, Moffatt CJ, et al. Lymphoedema: estimating the size of the problem. Palliative medicine 2005 Jun;19(4):300-13. doi:10.1191/0269216305pm1020oa. PubMed PMID: 15984502; eng.

- Lerman M, Gaebler JA, Hoy S, et al. Health and economic benefits of advanced pneumatic compression devices in patients with phlebolymphedema. J Vasc Surg 2018 Jun 15. pii: S0741-5214(18)30983-2. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2018.04.028. PubMed PMID: 29914829; eng.

- Sayko O, Pezzin LE, Yen TW, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of lymphedema after breast cancer: a population-based study. PM & R 2013;5:915-23.

- Yost KJ, Cheville AL, Al-Hilli MM, et al. Lymphedema after surgery for endometrial cancer: prevalence, risk factors, and quality of life. Obstet Gynecol 2014;124(2 Pt 1):307–15.