Abstract

Objectives: Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) is a rare genetic disorder associated with varying degrees of hyperphagia, obesity, intellectual disability, and anxiety across the affected individuals’ lifetimes. This study quantified caregiver priorities for potential treatment endpoints to identify unmet needs in PWS.

Methods: The authors partnered with the International Consortium to Advance Clinical Trials for PWS (PWS-CTC) and a diverse stakeholder advisory board to develop a best–worst scaling instrument. Seven relevant endpoints were assessed using a balanced incomplete block design. Caregivers were asked to determine the most and least important of a sub-set of four endpoints in each task. Caregivers were recruited nationally though patient registries, email lists, and social media. Best–worst score was calculated to determine caregiver priorities; ranging from 0 (least important) to 10 (most important). A novel kernel-smoothing approach was used to analyze caregiver endpoint priority variations with relation to age of the PWS individual.

Results: In total, 457 caregivers participated in the study. Respondents were mostly parents (97%), females (83%), and Caucasian (87%) who cared for a PWS individual ranging from 4–54 years. Caregivers value treatments addressing hyperphagia (score = 7.08, SE = 0.17) and anxiety (score = 6.35, SE = 0.16) as most important. Key variations in priorities were observed across age, including treatments targeting anxiety, temper outbursts, and intellectual functions.

Conclusions: This study demonstrates that caregivers prioritize hyperphagia and, using a novel method, demonstrates that this is independent of the age of the person with PWS. This is even the case for parents of young children who have yet to experience hyperphagia, indicating that these results are not subject to a hypothetical bias.

Introduction

Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) is a rare genetic disorder affecting 1 in 25,000 peopleCitation1. PWS results from the loss of expression of genes on chromosome 15q11-q13Citation2,Citation3. It is sporadic in nature, and typically occurs randomly in individuals without a family history of PWSCitation3. Common features of the syndrome include varying degrees of hyperphagia, obesity, intellectual disability, and anxiety across the affected individuals’ lifetimesCitation3–6. Lifetime care for PWS incurs 8.8-times higher medical costs compared to unaffected individuals and presents a significant economic burden for both the family and societyCitation7,Citation8. One of the most prominent characteristics of PWS is hyperphagia, which is stressful and life-threatening for people with PWSCitation9. Hyperphagia in PWS presents with an insatiable appetite and difficult behavior around foodCitation10. Uncontrolled hyperphagia can lead to obesity and other comorbidity, which constitute the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in PWSCitation9–11.

PWS is currently managed with dietary and environmental restrictions, behavioral modifications, growth hormone, and other supportive treatmentsCitation12,Citation13. PWS individuals’ clinical presentations may vary based on different genetic sub-types and age groupsCitation13,Citation14. A multidisciplinary team with age-dependent treatment plans are recommended for the management of PWSCitation12,Citation13. Growth hormone replacement therapy (GHRT) is the standard of care for children with PWS and is commonly prescribed in infants and adultsCitation11. GHRT improves growth and body composition, but has no effect on hyperphagia in PWSCitation13. Several clinical trials have been initiated to examine the effects of emergent treatment options addressing hyperphagia in PWSCitation11,Citation15. Beloranib manufactured by Zafgen showed promising results in suppressing hyperphagia, but was terminated due to severe adverse events occurring during phase IIICitation16. Bariatric surgical options such as biliopancreatic diversion (BPD) and gastric bypass have been used to promote weight loss in PWS. However, bariatric surgical options for weight loss in the PWS population resulted in poor outcomes and dire post-surgical sequelae such as fatty liver, pulmonary embolism, and deathCitation17.

There is currently no FDA-approved cure for PWS, nor effective treatment for hyperphagia in PWSCitation11. To accelerate the development and approval of PWS treatments, a rare disease patient organization called the International Prader-Willi Syndrome Clinical Trials Consortium (PWS-CTC) was launched in 2015Citation18. The Consortium is administered by the Foundation for Prader-Willi Research (FPWR), a non-profit patient organization focused on advancing the understanding and treatment of PWSCitation19. As part of an effort to explore the clinical unmet needs of the PWS community, FPWR developed and administered an online survey named “Patient Voices” through online platforms, and received 779 caregiver responsesCitation20. The results of the patient voice survey demonstrated caregiver priorities, but the methods used are less rigorous compared to standard patient preference elicitation techniquesCitation21,Citation22, and do not comply with many of the FDA recommended qualities of patient preference studiesCitation23.

We sought to quantify caregiver priorities for possible treatment endpoints to identify unmet needs and to investigate how clinical endpoint prioritization varies across the natural history of the disorder. Our work builds on previous efforts by the PWS community to raise awareness of the unmet clinical needs. As such, we contribute to the growing literature demonstrating methods to foster a culture of patient-focused drug developmentCitation24,Citation25.

Methods

We utilized current best practices for community-engagement research to guide this studyCitation23,Citation26. A Community Advisory Board (CAB) was assembled with PWS patients (2), PWS caregivers (6), and clinicians specializing in PWS (2)Citation23,Citation26. The CAB provided guidance throughout the study. We also engaged caregivers in the PWS community to develop a patient-centered patient preference surveyCitation27. This engagement impacted the design, length, and wording of the instrument. In addition to the choice tasks, the survey also included demographic questions, and a set of standardized questions and free text section to assess the respondents’ level of acceptance of the instrument. The standardized questions ask the respondents whether they agree with the following three statements using a Likert scale for assessment: (a) I found it easy to understand the questions; (b) I found it easy to answer the questions; and (c) My answers showed my real preferences. The free text section asked the caregivers to provide their feedback on the survey.

Best–worst scaling (BWS) case 1 was chosen among several stated-preference methods considered, due to its simplicity, low respondent burden, and strengths in measuring prioritiesCitation28–30. Respondents were asked to compare a sub-set of treatment benefits in each task and determine the most and least important benefits for their family member with PWSCitation21. The instrument was first tested in “proof of concept” and then underwent a pre-test and pilot prior to the national launch. We evaluated the feasibility of the methods and ensured the patient-centeredness of the survey through these study activitiesCitation22.

Proof of concept

The objective of the “proof of concept” was to examine the feasibility of employing stated-preference instruments in the PWS population. We designed a survey using the best–worst scaling method with 13 objects. The 13 objects were chosen based on a literature review, previous research from FPWR, and input from the PWS community advisory board. A balanced incomplete block design (BIBD) was used to construct 13 choice tasks to evaluate the priority of the 13 objects. The “balanced” in the BIBD means that each object appears the same number of times and each pair of objects appears together the same number of times in choice tasks (blocks), while the “incomplete” indicates that not all objects are included in each choice taskCitation31. The respondents were presented with four outcomes in each task, where they were asked to pick one as the most important and one as the least important. The choice tasks were framed using a community perspective where caregivers were asked to select the most and least important outcome when considering a treatment for the PWS individual in general.

We tested the survey in the PWS community using a novel method called research as an eventCitation25, by attending the 2016 FPWR Annual Family conference to conduct qualitative interviews and distribute the survey. Fifteen caregivers participated in the interviews and 53 caregivers completed the survey. The findings of the qualitative interviews showed that the caregivers understood the survey design and framing of the question. The results of the initial pilot demonstrated the feasibility of implementing stated-preference methods in the PWS population.

Pre-test and pilot

We conducted a series of pre-test interviews to ensure the caregivers were able to understand the survey questions and answer accordingly. We also refined the object list so that it would be relevant to the community. Pre-test participants were caregivers recruited through the communication channels of PWS-CTC. Pre-test interviews were conducted in the format of ‘read through’ cognitive interviews where participants were asked to review the survey page-by-page and provide input on the design, clarity, and relevance of the surveyCitation32. Specifically, the participants were asked to review the instructions and inform the interviewer how they would answer the survey without any coaching from the interviewer. The participants were also asked if the objects are all relevant to the community and if the descriptions of the object list were easy to understand.

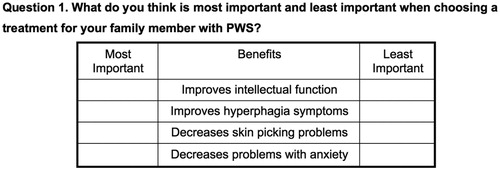

The pre-test findings demonstrated that the caregivers had an excellent understanding of the survey questions and instructions (an example of the question is shown in ). The caregivers preferred a change in the framing of the question (from what’s most/least important for a “PWS individual in general” to “PWS family member”), because PWS individuals may have different manifestations of the disorder, thus it was challenging for the caregivers to take on a community perspective and determine the priorities for a “PWS individual in general”. They also preferred the objects to be named “treatment benefits” instead of “treatment outcomes”.

The pre-test findings also showed that some of the objects were less relevant to the community, or could be combined, which resulted in a refinement of the object list (from 13 to 7 items, listed in ). A pilot was conducted prior to the national launch, and pilot findings demonstrated face validity based on the feedback from the community advisory board.

Table 1. List of treatment benefits and description.

Recruitment

Caregivers were qualified for the national survey if they were adult primary caregivers. Adult primary caregivers are defined as (1) a parent, grandparent, sibling, or legal guardian of a family member with PWS; (2) having a family member with PWS who is 4 years old or older; and (3) have been involved in the decision-making process for the care and treatment of the person with PWS. The cut-off point was set at 4-years-old, since individuals with PWS start to experience major PWS symptoms such as hyperphagia beginning around the age of 4 yearsCitation33.

The respondents completed seven BWS choice tasks to assess the seven objects (treatment benefits) in the national survey. The 7-object survey was administered online nationally via Qualtrics and deemed exempt by the IRB at JHSPH (IRB00007769). We recruited PWS caregivers through the digital platform on PWS-CTC’s website, the Global PWS Registry, PWS-associated Facebook groups, E-mail lists, blogs, and newsletters of the Foundation for Prader-Willi Research (FPWR) and Prader-Willi Syndrome Association (USA) (PWSA (USA)). No incentives were provided for caregivers who participated in our study.

Data analysis

The contents of the qualitative interviews were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using thematic analysisCitation34,Citation35. STATA version 14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) was used to compute the demographics and the best–worst scores per object. A best–worst (BW) score was calculated by adding the number of times a benefit was voted as best, and subtracting the number of times the benefit was chosen as worst, accumulating across all respondents. This was then divided by the number of the times each benefit was shown to all respondentsCitation36. As all benefits were considered to have positive utility, we rescaled each score to range from 0 (the least possible benefit) to 10 (the highest possible benefit).

To assess the sensitivity of our results across our sample, we modeled this score across the age of the person with PWS. This is important, as the natural history of PWS is that manifestations vary across the lifetime of an affected individual, and this may impact caregivers’ assessment of unmet needCitation3,Citation5,Citation6. We used a kernel-weighted local polynomial smoothing technique to graph these variationsCitation37.

Results

Demographics and survey assessment

A total of 457 caregivers completed the BWS choice tasks. The mean age of caregivers was 48.8 years (range = 20–85). Most of the caregivers were parents (97%), females (83%), and Caucasian (87%). Half of the caregivers had an annual household income over $100,000 (50%). Caregivers were well-educated and well-informed; 70% of caregivers had at least a bachelor’s degree, and 46% were at least somewhat familiar with the FDA; 89% of caregivers were located in the US.

The caregivers provided information about their PWS family member and offered their feedback on the survey using the assessment questions and the free text section. The average age of the PWS individual was 15.6 years (range = 4–54 years). Most of the PWS patients were diagnosed through genetic testing (97%); deletion (50%) and uniparental disomy (37%) were the most common genetic sub-types. When asked the assessment questions, 85% of the caregivers found it easy to understand the questions, 72% found it easy to answer the questions, and 84% of the caregivers agreed that the answers showed their real preferences. The free text section showed that some of the caregivers considered the best–worst scaling challenging, stating “I find the preference questions hard to answer because we want it all for our daughter”. Results of the demographics of caregiver and the PWS individual are documented in .

Table 2. Demographics of the participants (n = 457).

Best–worst scaling

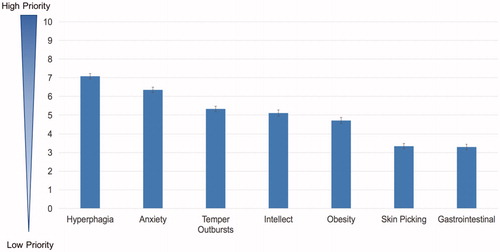

demonstrates the results of the best–worst score and their 95% confidence intervals. A best–worst score of 0 is considered as lowest priority and 10 is considered as highest priority. The best–worst score showed that the respondents, on average, considered a treatment that “improves hyperphagia symptoms” (score = 7.08, SE = 0.07) and “decreases problems with anxiety” (score = 6.35, SE = 0.07) as most important for their family member with PWS, which is consistent with the pilot findings. The least important of the treatment benefits are “decreases skin picking problems” (score = 3.33, SE = 0.08) and “decreases gastrointestinal problems” (score = 3.29, SE = 0.07). The least important treatment benefits do not imply that those issues are not relevant or important to the community, but, rather, they are of lower priority compared to other treatment benefits on the list. One caregiver stated in the free text section, “the items I marked ‘least important’ were actually items that all matter to me and … my daughter’s quality-of-life and that of all the family”.

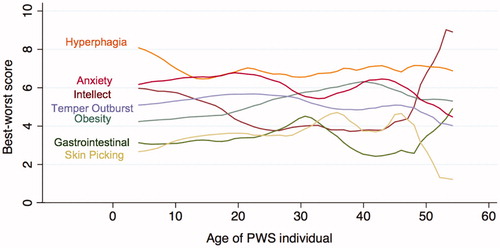

shows the result of the best–worst score mapped against the age of the PWS family member using kernel smoother for estimation. This figure demonstrates the variation of caregiver priorities throughout the natural history of the disorder. “Improves hyperphagia symptoms” (Hyperphagia) is consistently considered most important by caregivers caring for all age groups. “Decreases problems with anxiety” (Anxiety) is closely tied with hyperphagia and ranked high on the caregivers’ list. “Decreases overweight problems” (Obesity) rises in importance as the individual ages. “Improves intellectual function” (Intellect) drops in significance between the 20–40 age group, but was considered very important after the age of 42. The priority of “Decreases temper outbursts” (Temper outburst) slowly begins to decline when the individual reaches the 30+ age group. “Decreases skin picking problems” (Skin picking) and “Decreases gastrointestinal problems” (Gastrointestinal) were considered by all age groups as the least important of the benefits listed. The changes in priorities as the PWS individual ages were consistent with the free text feedback from the caregivers, where one caregiver stated, “the importance of the different categories changes as the child ages”.

Discussion

The significance of hyperphagia as an unmet need is well known in the PWS community. This study helps to rigorously quantify the importance of hyperphagia and demonstrates that it is independent of the age of the person with PWS. This work also adds to the growing literature demonstrating the value of quantitative stated-preference methods to foster patient-focused drug development and focused endpoint selectionCitation24,Citation26,Citation38.

In this work, we demonstrated that hyperphagia is the highest priority treatment benefit in the PWS community and is distinct from obesity in caregiver priorities. Without diet control and environmental restrictions, hyperphagia and obesity in PWS go hand in handCitation9. However, with dietary and environmental restrictions in place (such as locking the food cabinets and refrigerators), PWS individuals can present with a normal body mass index (BMI) and still be greatly affected by hyperphagiaCitation39, preventing these individuals from being truly independent in life. Current medication trials have targeted hyperphagia, but many have excluded PWS individuals without obesityCitation11. It is clear from our study that hyperphagia is an unmet need in the PWS community, warranting an effective treatment option for PWS individuals with and without obesity. This is also an example of how patient and caregiver perspectives could be beneficial in clinical trial endpoint selections, echoing the calls of more patient involvement in clinical researchCitation40,Citation41.

Researchers have developed metrics to measure hyperphagia to demonstrate the effect of the emerging treatments for hyperphagia, acknowledging that BMI is not a valid index for measuring hyperphagiaCitation39,Citation42. Several methods have been developed, including behavioral observations, visual analog interview scales, self- or caregiver administered questionnaires, and an eye-tracking deviceCitation39,Citation42. The hyperphagia questionnaire for clinical trials (HQ-CT), in particular, has been considered by PWS-specialized clinicians as the gold standard to assess hyperphagiaCitation16. HQ-CT asks PWS caregivers to assess their family members on nine food-related behaviors during the past 2 weeks, and generates a score ranging from 0–36Citation9. However, there has been little data as to whether or not an improvement on each of the food-related behaviors listed on the HQ-CT represent the same improvement in hyperphagia from the caregivers’ or the patients’ perspective. Furthermore, a clinical meaningful benefit or a statistically significant impact may not necessarily equate to a meaningful impact on quality-of-life, or, possibly more likely, a relatively trivial improvement in the HQ-CT score may represent a large improvement in quality-of-life for the person with PWS and their caregivers. It is, therefore, critical to engage patients and their caregivers to understand and measure what matters to them. Further research is needed to evaluate current methods of measuring hyperphagia from the patients’ and caregivers’ perspective.

There has been an on-going debate of the extent of hypothetical bias in stated-preference studies, especially as it relates to economic values such as willingness to payCitation43,Citation44. Stated-preference (SP) research methods are methods used by researchers to understand how individuals behave in a controlled settingCitation45. Generally, SP methods provide participants with a hypothetical scenario to understand what the participants value and what decisions they would make under certain circumstancesCitation45. It helps the researcher to understand what motivates an individual’s behavior and can predict how the individual would make decisions in the real worldCitation45. However, because of the hypothetical nature of SP studies, questions have been raised on whether the individual’s decision would differ in a hypothetical scenario compared to a real-life situationCitation43,Citation44. We hope to shed some light on the question of hypothetical bias through our study.

In this study, we demonstrated through the sensitivity analysis that hyperphagia is the most prioritized treatment benefit in PWS, independent of the age of the PWS individual (). This is especially significant given the average onset of full-on hyperphagia is 8 years oldCitation33, meaning that some caregivers in the study have not yet experienced hyperphagia or hyperphagia to its full extent. In this study, whether it is a hypothetical scenario (caregivers who have not experienced hyperphagia) or a real-life situation (caregivers with hyperphagia experience), there was no difference in how caregivers answered the question, implying that there was no hypothetical bias in this study population.

Additionally, we showed how patient preference information could change over time as the disease progresses (). In general, treatment endpoint prioritization has been shown to be highly correlated with clinical manifestation of a disorderCitation46. Clinical manifestations and problems in PWS vary over the age span of the affected individual, so it is not surprising that caregiver treatment priorities would vary over time, as demonstrated in . The clinical experts on the advisory board endorse these results based on their clinical observations.

There are several limitations of our study. First, we used caregivers as surrogates, and the patients’ perspectives have not been fully explored. In the planning phase of our study, we explored the possibility of eliciting patients’ perspectives as well as the caregivers’. However, PWS individuals commonly present with a lower than average IQCitation3, which begs the question of whether or not they can truly consent. There is no doubt that the patient population of PWS has yet to be fully empowered and activated. In future studies, we hope to engage the patient population and to better understand their point of view, recognizing that the constant sense of hunger ensures that there will be conflict between what is needed to maintain reasonably good health (reduced intake of calories) and what the priority felt by the patient would be (increased intake of calories). That said, individuals with PWS can articulate that the constant sense of hunger is distressing to them.

We set a screening criteria for primary adult caregivers, but we did not use measures to prevent multiple respondents (i.e. both parents in a family) to answer the survey about the same individual with PWS. In pre-testing and piloting the survey, we learned that caregivers caring for the same PWS individual may have different insight toward the unmet needs and have distinct treatment priorities. It is a unique characteristic of stated-preference research that, given the same facts (symptoms and conditions of the same PWS individual), respondents may have different perspectives (treatment priorities). This mirrors real-life situations, in that different factors personal to each individual (i.e. background, knowledge, personality) drives his/her decision-making process. We believe that, by not turning away any primary caregivers in the family, we could further empower caregivers in the PWS community to engage and become their own advocates.

Some may view BWS as a simple ranking technique. While this could be debated, our results do not indicate how much more important hyperphagia is than other outcomes. As such, it may be less informative for structured benefit–risk analysis or economic evaluation of an eventual therapy targeting hyperphagia. Other stated-preference techniques, such as a discrete-choice experiment, could be used to explore the tradeoffs that caregivers are willing to make in order to treat hyperphagia. Likewise, traditional health state utility measures, such as time-trade off, could be used to demonstrate the effects of treating hyperphagia on overall quality-of-life. Our goal was to highlight the unmet clinical need in PWS. As such, we are targeting decisions earlier in the project lifecycle, such as choice of target in early stage development and clinical trial designCitation47.

We interpreted the findings of caregivers prioritizing hyperphagia consistently across all age groups, as there is no hypothetical bias in this population. Other factors may have influenced the findings. For instance, we recruited caregivers through partnering with various PWS patient organizations where caregivers connect and exchange information. Patient organizations provide a platform for caregivers to receive latest published research, clinical trial information, and emotional support. Caregivers of younger children may have received information of the significance of hyperphagia or learned of their hyperphagia experiences from caregivers of older children in the community through their patient organization connections. However, we specifically framed the survey questions so that caregivers were asked to choose the treatment benefit “for their family member”. Also, we learned in the pre-test interviews that caregivers actually preferred considering treatments “for their family member” over “PWS individual in general”. They mentioned that, even when we framed the question and asked them to choose the treatment benefit for “PWS individuals in general”, most of them would still consider their family member because it is personal to them. They have also acknowledged that, since PWS is a broad-spectrum disorder and each individual presents differently, it would be a challenge for them to decide for someone else.

Another explanation could be that caregiver priorities of younger children could present with a higher variability, but were masked when the results were aggregated. In order to map the treatment priorities over time, caregiver priorities of PWS individuals of the same age were aggregated and estimated. Hyperphagia has been ranked consistently high, but there could be variability within caregiver priorities of the same age. High variability could occur in caregivers with younger children, where caregivers with hyperphagia and non-hyperphagia experiences may have behaved differently. We included 457 caregiver responses in this study, which is a relatively significant sample size given that this is a rare disease population. However, by dissecting their priorities using the age of the PWS individual, we further segmented the sample. The validity of the results would be challenged if we attempt to further dissect and investigate the variability of caregiver priorities by age. Future research with a larger sample size would be beneficial to address the concerns of caregiver priority variability.

In our sensitivity analysis, we hope to answer the question of how priorities would change over time. However, this study is a cross-sectional study and serves only as an estimation of how priorities can change throughout the lifetime of a PWS individual. Fully investigating treatment priorities across the lifetime of a PWS individual would require following PWS individuals throughout their lifetime, which is not realistic in the time frame of meaningful treatment development now. One of the main findings of our sensitivity analysis is to demonstrate that hyperphagia is regarded as the most important treatment benefit by all age groups. The findings of our study showed no indication that a longitudinal follow-up study spanning over the lifetime of a PWS individual would behave differently, however it cannot be generalized for other populations. A longitudinal study would be beneficial to further investigate the effects of preference changing over time.

Conclusions

In this first study to map preferences across the lifetime, we demonstrate the importance of hyperphagia, even in patients who are too young to have experienced it, quelling concerns about hypothetical bias. While we also pave the way for larger and longitudinal studies of preference, we illustrate that preferences for endpoints do not vary as much as some have assumed.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by a grant from the International Consortium to Advance Clinical Trials for PWS (PWS-CTC). The purpose of this funding is to understand patient perspectives.

Declaration of financial/other interests

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from that disclosed. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Previous presentations

This study was presented at the 22nd and 23rd Annual Meeting of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research as poster presentations.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the leadership and dedication of the community advisory board, including Theresa Strong, Nathalie Kayadjanian, Ann Scheimann, Shawn McCandless, Lauren Roth, Emma Roth, Sara Cotter, Maria Picone, Rob Lutz, Vonnie Sheadel, John Heybach, Conner Heybach, and Mark Greenberg, that contributed in the study design and the survey development. We are grateful for the caregivers who responded to the survey, and Winter Maxwell Thayer, who assisted in the recruitment, qualitative interviews, and survey data imputation. Special thanks to the Prader-Willi Syndrome Association and Foundation for Prader-Willi Research for assisting with recruitment.

References

- Orphanet: Prader Willi syndrome [Internet]. Paris, France; 2007. Available at: http://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/OC_Exp.php?Expert=739 [Last accessed 31 August 2018]

- Goldstone AP, Aronne LJ. Prader-Willi syndrome: advances in genetics, pathophysiology and treatment. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2003;15:12-20

- Cassidy SB, Driscoll DJ. Prader-Willi syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet 2009;17:3-13

- Angulo MA, Butler MG, Cataletto ME. Prader-Willi syndrome: a review of clinical, genetic, and endocrine findings. J Endocrinol Invest 2015;38:1249-63

- Griggs JL, Sinnayah P, Mathai ML. Prader–Willi syndrome: from genetics to behaviour, with special focus on appetite treatments. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2015;59:155-72

- Cohen M, Hamilton J, Narang I. Clinically important age-related differences in sleep related disordered breathing in infants and children with Prader-Willi syndrome. PLoS One 2014;9:e101012

- López-Bastida J, Linertová R, Oliva-Moreno J, et al. Social/economic costs and health-related quality of life in patients with Prader-Willi syndrome in Europe. Eur J Heal Econ 2016;17:99-108

- Chevreul K, Berg Brigham K, Clément M-C, et al. Economic burden and health-related quality of life associated with Prader-Willi syndrome in France. J Intellect Disabil Res 2016;60:879-90

- Dykens EM, Maxwell MA, Pantino E, et al. Assessment of hyperphagia in Prader-Willi syndrome. Obesity 2007;15:1816-26

- Goldstone AP, Holland AJ, Butler J V, et al. Appetite hormones and the transition to hyperphagia in children with Prader-Willi syndrome. Int J Obes 2012;36:1564-70

- Miller J, Strong T, Heinemann J. Medication trials for hyperphagia and food-related behaviors in Prader–Willi syndrome. Diseases 2015;3:78-85

- Goldstone AP, Holland AJ, Hauffa BP, et al. Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Prader-Willi syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:4183-97

- Cassidy SB, Schwartz S, Miller JL, et al. Prader-Willi syndrome. Genet Med 2012;14:10-26

- Butler MG, Thompson T. Prader-Willi syndrome: clinical and genetic findings. Endocrinologist 2000;10:3S-16S

- Prader-Willi Syndrome Association (USA). Summary of active clinical trials for Prader-Willi syndrome hyperphagia [Internet]. Sarasota, FL; c2016. Available at: https://www.pwsausa.org/summary-active-clinical-trials-prader-willi-syndrome-hyperphagia/ [Last accessed 31 August 2018]

- McCandless SE, Yanovski JA, Miller J, et al. Effects of MetAP2 inhibition on hyperphagia and body weight in Prader-Willi syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Obes Metab 2017;19:1751-61

- Scheimann A, Butler M, Gourash L, et al. Critical analysis of bariatric procedures in Prader-Willi syndrome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2008;46:80-3

- PWS Clinical Trials Consortium [Internet]. c2016. Available at: https://www.pwsctc.org/ [Last accessed 4 May 2017]

- Foundation for Prader-Willi Research [Internet]. Walnut, CA, USA; c2018. Available at: https://www.fpwr.org/ [Last accessed 14 April 2017]

- Theresa S. PWS Patient Voices [Internet]. Walnut, CA, USA: Foundation for Prader-Willi Research; 2014. Available at: https://www.fpwr.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/PatientVoices_presentationWebinarFinal.pdf [Last accessed 10 July 2018]

- Flynn TN, Louviere JJ, Peters TJ, et al. Best–worst scaling: what it can do for health care research and how to do it. J Health Econ 2007;26:171-89

- Janssen EM, Segal JB, Bridges JFP. A framework for instrument development of a choice experiment: an application to type 2 diabetes. Patient 2016;9:465-79

- Patient Preference Information – Voluntary submission, review in premarket approval applications, humanitarian device exemption applications, and de novo requests, and inclusion in decision summaries and device labeling guidance for industry, food and drug administration staff, and other stakeholders. Silver Spring, MD, USA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration; 2016

- Perfetto EM, Burke L, Oehrlein EM, et al. Patient-focused drug development: a new direction for collaboration. Med Care 2015;53:9-17

- Tsai J-H, Janssen E, Bridges J. Research as an event: a novel approach to promote patient-focused drug development. Patient Prefer Adherence 2018;12:673-9

- Peay HL, Hollin I, Fischer R, et al. A community-engaged approach to quantifying caregiver preferences for the benefits and risks of emerging therapies for duchenne muscular dystrophy. Clin Ther 2014;36:624-37

- Hollin IL, Young C, Hanson C, et al. Developing a patient-centered benefit-risk survey: a community-engaged process. Value Heal 2016;19:751-7

- Severin F, Schmidtke J, Mühlbacher A, et al. Eliciting preferences for priority setting in genetic testing: a pilot study comparing best-worst scaling and discrete-choice experiments. Eur J Hum Genet 2013;1202-8

- van Dijk JD, Groothuis-Oudshoorn CGM, Marshall DA, et al. An empirical comparison of discrete choice experiment and best-worst scaling to estimate stakeholders’ risk tolerance for hip replacement surgery. Value Heal 2016;19:316-22

- Krucien N, Watson V, Ryan M. Is best-worst scaling suitable for health state valuation? A comparison with discrete choice experiments. Health Econ 2017;26(12):e1–e16

- Kuhfeld WF. Marketing research methods in SAS. Cary, NC, USA: SAS Institute Inc.; 2010. Available at: https://support.sas.com/techsup/technote/mr2010.pdf [Last accessed 9 March 2017]

- DeMuro CJ, Lewis SA, DiBenedetti DB, et al. Successful implementation of cognitive interviews in special populations. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2012;12:181-7

- Miller JL, Lynn CH, Driscoll DC, et al. Nutritional phases in Prader-Willi syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 2011;155A:1040-9

- Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci 2013;15:398-405

- Braun V, Clarke V. Qualitative research in psychology using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77-101

- Louviere JJ, Flynn TN, Marley AAJ. Best-worst scaling: theory, methods and applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2015

- Wand MP, Jones MC. Kernel smoothing. Boca Raton, FL, USA: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 1995

- Janssen EM, Benz HL, Tsai J-H, et al. Identifying and prioritizing concerns associated with prosthetic devices for use in a benefit-risk assessment: a mixed-methods approach. Expert Rev Med Devices 2018;15:385-98

- Key AP, Dykens EM. Eye tracking as a marker of hyperphagia in Prader-Willi syndrome. Dev Neuropsychol 2018;43:152-61

- Mullins CD, Vandigo J, Zheng Z, et al. Patient-centeredness in the design of clinical trials. Value Heal 2014;17:471-5

- Sacristán JA, Aguarón A, Avendaño-Solá C, et al. Patient involvement in clinical research: why, when, and how. Patient Prefer Adherence 2016;10:631-40

- Dykens EM, Roof E. Behavior in Prader-Willi syndrome: relationship to genetic subtypes and age. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2008;49:1001-8

- Murphy JJ, Allen PG, Stevens TH, et al. A meta-analysis of hypothetical bias in stated preference valuation. Environ Resour Econ 2005;30:313-25

- Loomis J. What’s to know about hypothetical bias in stated preference valuation studies? J Econ Surv 2011;25:363-70

- Bridges JF, Wu AW, Jodi Segal F, et al. White paper #1: Stated-preference methods Baltimore, MD, USA: The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; 2014

- Pituch KA, Green VA, Didden R, et al. Parent reported treatment priorities for children with autism spectrum disorders. Res Autism Spectr Disord 2011;5:135-43

- Medical Device Innovation Consortium. Medical Device Innovation Consortium (MDIC) Patient Centered Benefit-Risk Project (PCBR) Appendix A: catalog of methods for assessing patient preferences for benefits and harms of medical technologies. Arlington, VA, USA: Medical Device Innovation Consortium; 2015