Abstract

Aims: Patients with classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma (cHL) who have relapsed after or are ineligible for autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) have limited treatment options and generally a poor prognosis. Pembrolizumab was recently approved in the US for the treatment of such patients having demonstrated clinical benefit and tolerability in relapsed/refractory cHL; however, the cost-effectiveness of pembrolizumab in this population is currently unknown.

Materials and methods: A three-state Markov model (progression-free [PF], progressed disease, and death) was developed to assess the cost-effectiveness of pembrolizumab (200 mg) vs brentuximab vedotin (BV; 1.8 mg/kg) in patients with relapsed/refractory cHL after ASCT who have not received BV post-ASCT over a 20-year time horizon from a US payer perspective. PF survival was modeled using a naïve indirect treatment comparison of data from KEYNOTE-087 and the SG035-003 trial. Post-progression survival was modeled using data from published literature. Costs (drug acquisition and administration, disease management, subsequent treatment, and adverse events) and outcomes were discounted at an annual rate of 3.0%. Uncertainty surrounding cost-effectiveness was assessed via probabilistic, deterministic, and scenario analyses.

Results: In the base case, pembrolizumab was predicted to yield an additional 0.574 life-years (LYs) and 0.500 quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) vs BV and cost savings of $63,278. Drug acquisition costs were the biggest driver of incremental costs between strategies. Pembrolizumab had a 99.6% probability of being cost-effective compared with BV at a willingness-to-pay threshold of $20,000/QALY and dominated BV in all scenarios tested.

Limitations: The analysis was subject to potential bias due to the use of a naïve indirect treatment comparison and, given the current immaturity of OS in KEYNOTE-087, PPS was assumed equivalent across both treatments.

Conclusion: Pembrolizumab is a cost-effective alternative to BV for patients with relapsed/refractory cHL after ASCT.

Introduction

Classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma (cHL) accounts for ∼95% of all Hodgkin’s lymphoma casesCitation1 and is characterized by the proliferation of abnormal B lymphocytes. It is a rare tumor type, accounting for ∼0.6% of all new cancer cases in the developed world. In the US, there are an estimated 8,400 new cases of cHL annually, comprising 8.7% of all lymphomasCitation2,Citation3. The first line of treatment for cHL is combination chemotherapy, where a 12-year progression-free survival rate of up to 92% in early favorable stage diseaseCitation4 and 10-year progression-free survival rates of up to 82% in advanced stage diseaseCitation5,Citation6 have been observed. For patients with primary relapse or refractory disease, the standard of care is salvage chemotherapy, followed by high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT)Citation7. ASCT is associated with relatively positive outcomes, with long-term progression-free survival achieved in ∼50–60% of relapsed patients and 30–40% of primary refractory patientsCitation8–15. Nonetheless, patients with relapsed or refractory cHL (RRcHL) following ASCT currently have limited treatment options and a poor prognosis, with median overall survival of ∼1–2 yearsCitation16–18. Until recently, brentuximab vedotin (BV) and nivolumab were the only approved options for treatment after ASCT.

Pembrolizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that blocks the interaction between the programmed death 1 (PD-1) receptor and its ligands. Pembrolizumab was granted accelerated approval by the FDA in March 2017 for the treatment of adult and pediatric patients with refractory cHL or those who have relapsed after three or more prior lines of therapy based on a Phase II, open-label multicenter study, KEYNOTE-087Citation19. Due to the high unmet need in cHL, pembrolizumab was approved for a broader patient population than that investigated in the trialCitation19.

The objective of this analysis was to estimate the cost-effectiveness of pembrolizumab vs BV in a patient population relevant to the approved population from a US payer perspective.

Methods

A model-based decision-analytic analysis was developed to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of treating RRcHL patients with pembrolizumab compared with BV. The results are presented as an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) using the quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained.

Treatment population

The model population adopted the demographic and clinical profile of select patients enrolled in cohort 3 of the KEYNOTE-087 study. Trial eligibility criteria included patients with RRcHL who had failed to achieve a response or progressed after ASCT and had not received BV post-ASCT. The baseline population characteristics applied in the base case model were (n = 60): mean age = 36.8 years; 43.3% female; mean body surface area = 1.90 m2 (SD = 0.28); and mean weight = 76.14 kg (SD = 20.64).

Model structure

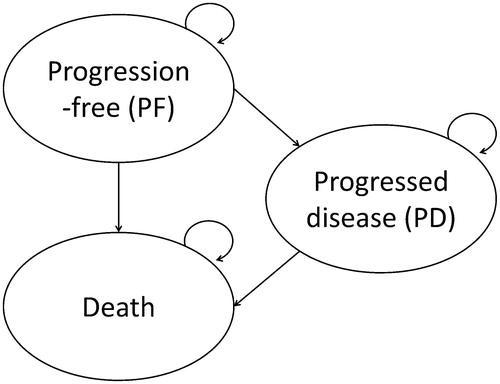

A Markov health state simulation model was developed with a 1-week cycle length to estimate health outcomes and costs for each treatment. The model included three mutually exclusive health states: progression-free (PF), progressed disease (PD), and death ( In KEYNOTE-087, progression was defined by independent review committee (IRC) assessment using International Working Group criteriaCitation20.

Figure 1. Transition state Markov model. All patients with RRcHL enter the model in the progression-free state. Patients are initiated on pembrolizumab or BV. In each model cycle, patients can remain progression-free, transition to progressed disease, or die. Patients with progressed disease can only transition to the death state.

All patients entered the model in the PF state and received treatment with either pembrolizumab (200 mg every 3 weeks until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity or up to 24 months in patients without disease progression) or BV (1.8 mg/kg every 3 weeks until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity for up to 16 cycles)Citation19,Citation21.

In KEYNOTE-087, an insufficient number of death events were observed (n = 4) to permit a reliable prediction of long-term overall survival (OS), parametric models fitted to the observed KEYNOTE-087 data predicted OS ranging from 8.6–85.9% at 40 years. For this reason, a Markov state transition model was preferred over the traditional, more commonly used partitioned survival model for the base case analysis. The Markov model was able to overcome the issue of limited OS data by modeling death as an event that was conditional on patient status (PF or PD). The transition from PF to PD was modeled using progression-free survival (PFS) from KEYNOTE-087, while external evidence was used to model the transition from PF to death and PD to deathCitation22,Citation23. Importantly, the Markov model was found to yield plausible projections of long-term survival in RRcHL based on the available data. The base case OS modeling approach projected <1% of the population remained alive in the analysis, which is more plausible from a clinical aspect.

The base case analysis adopted a time horizon of 20 years to accommodate the life expectancy of this indicated population. Time horizons of 10 years and 30 years were tested as scenario analyses. Total costs and health outcomes over the time horizon were estimated by combining the number of patients in each health state with the costs and utilities associated with that health state. Costs and health outcomes were discounted at 3.0% per year, in line with US guidelinesCitation24. All costs were adjusted to 2017 USD. Discount rates were varied between 0.0% and 6.0% in the deterministic sensitivity analysis.

Clinical inputs

In the absence of head-to-head clinical trial data comparing pembrolizumab with BV, effectiveness parameters were estimated from KEYNOTE-087 patient-level data and a naïve indirect treatment comparison (ITC), which compared outcomes for BV in SG035-003 vs pembrolizumab in cohort 3 of KEYNOTE-087 without adjustment for differences in cohort characteristics or study design. Population-adjusted ITCs were attempted, including the use of a simulated treatment comparisonCitation25 approach to predict pembrolizumab outcomes in a group with comparable characteristics to the BV trial cohort. However, only a limited number of relevant prognostic factors and effect modifiers were identified for inclusion in the adjustment. Therefore, given the additional uncertainty associated with predictive models and the minimal difference in the results compared with the naïve analysis, the naïve analysis was applied in the base case. The naïve comparison ITC was conducted using Cohort 3 from KEYNOTE-087 with a data cut-off of September 25, 2016Citation26 and SG035-003, an open-label, Phase II trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of BV in patients with RRcHL after ASCTCitation27.

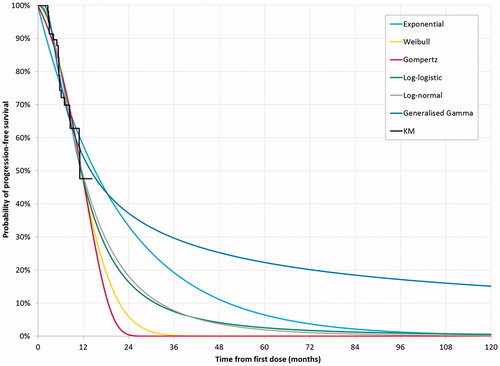

The Markov model requires three sets of transition probabilities: from PF to PD; from PF to death; and from PD to death. The transition probabilities from PF to PD were modeled using various parametric models fitted to the PFS data from KEYNOTE-087 and assessed in alignment with published methods, considering statistical fit, visual fit, and clinical plausibilityCitation28. The parametric models assessed included Weibull, exponential, log-normal, log-logistic, generalized gamma, and the Gompertz distributions. The distribution selection was first based on Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), the visual fit to the observed data and comparison of the long-term extrapolation trend to external data, after which clinical plausibility of the extrapolated results was verified by clinical experts.

PFS and OS

Median PFS for pembrolizumab was numerically greater than for BV (11.3 months vs 5.6 months). The PFS hazard ratio (HR) for the naïve indirect treatment comparison of BV compared with pembrolizumab was 1.79 (95% CI = 1.1–2.89), indicating that BV is associated with a significantly higher risk of progression than pembrolizumabCitation29.

Transition probabilities for PFS and OS

The log-normal distribution was applied for PFS in the base case model as it had the best statistical fit and a good visual fit to the observed data ( The log-normal curve was also the most clinically plausible extrapolation in the context of the PFS data from KEYNOTE-013 (a single-arm Phase Ib study that included a cohort of patients with RRcHLCitation29). The flattening of the PFS curve was supported by long-term PFS data from SG035-0003 for complete responders (CR) and non-CRCitation30.

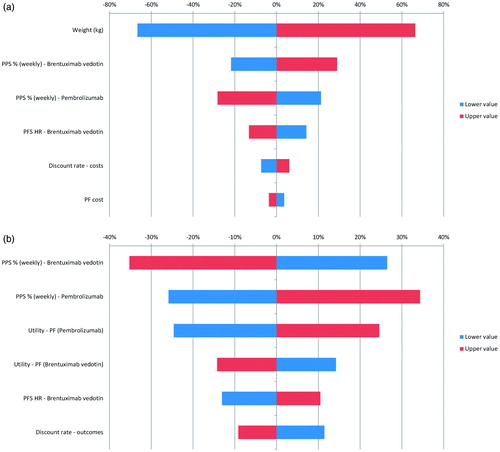

Figure 3. Deterministic sensitivity analysis results. (a) Incremental costs of pembrolizumab vs BV; (b) Incremental QALYs of pembrolizumab vs BV.

The generalized gamma was also considered as a plausible long-term extrapolation compared to the observed long-term data from SG035-0003, which established that a small proportion (9%) of patients treated with BV remained in long-term remission without additional lymphoma-directed therapyCitation30. However, given that the log-normal provided a more conservative incremental survival benefit, the generalized gamma was explored in scenario analysis.

Since there were too few deaths in KEYNOTE-087 at the time of the analysis to assess mortality, pre-progression mortality in the model was assumed to be the same as general population mortality, and was obtained from the US Life TablesCitation23.

At the time of analysis, the number of patients who progressed in KEYNOTE-087 was insufficient to support a robust analysis of post-progression survival (PPS). Instead, mortality data for patients with RRcHL who had progressed on treatment were taken from a study by Cheah et al.Citation22, a retrospective analysis of an institutional database that assessed the outcomes of 97 patients who received contemporary treatments after progression on BV. The reported median OS of 25.2 months was converted into a weekly probability of survival using standard techniques, and applied equally to both arms.

Adverse events

The model included the rates of all-cause adverse events (AEs) that had a severity grade of 3 or above and occurred in ≥5% of patients across the two studies ( Widening the inclusion criteria was not possible due to only limited adverse events being reported from SG035-003 (>10% any grade). However, this was likely to have a minimal impact on the analysis, given that no two patients experienced the same adverse event with severity grade of 3 or more on pembrolizumab (KEYNOTE-087 Cohort 3), demonstrating that there were no significant immunotherapy-related adverse events that would impact the costs or QALYs. AEs considered in the model included neutropenia, peripheral sensory neuropathy, thrombocytopenia, and anemia. The incidences of AEs for pembrolizumab and BV were obtained from KEYNOTE-087Citation26 and SG035-0003Citation27, respectively.

Table 1. Summary of model inputs.

Subsequent treatments

The distribution of patients across treatment options for subsequent therapy, after failure of BV or pembrolizumab, was assumed to be the same for both arms. Treatment options included: BV, 12.8% of patients; gemcitabine plus vinorelbine or gemcitabine plus vinorelbine plus pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, 10.5%; gemcitabine alone, 6.8%; and bendamustine, 4.6%Citation31. Some patients were not eligible to receive subsequent treatment, for reasons such as frailty, patient choice, or physician choice.

The duration of subsequent therapy was assumed to be the same across all treatments (4.47 monthsCitation22), given the nature of RRcHL whereby subsequent lines of therapy may be palliative in nature. The only exception was bendamustine, which was assumed to be given for a maximum treatment duration of six treatment cycles (3.70 months)Citation22.

Utility data

For the PF state, the utility value was derived from EQ-5D-3L domain scores from KEYNOTE-087, converted to a single utility value using published methods ()Citation32–34. The EQ-5D-3L was administered at treatment cycles 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 (that is, every 3 weeks), and then every 12 weeks thereafter until progression, while patients were receiving treatment with pembrolizumab. The same utility value was applied to the PF health state for both pembrolizumab and BV. The KEYNOTE-087 EQ-5D-3L data did not show a meaningful difference between PF and PD, because EQ-5D data were only collected 30 days post-treatment discontinuation, and were, therefore, judged to inadequately cover symptom burden expected during progressed disease. Therefore, utility for the PD state was taken from a published study in which subjects valued vignettes describing various health states associated with RRcHL and systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma using the time trade-off methodCitation35.

Table 2. Summary of model utility inputs.

Disutilities and mean durations for the AEs considered in the model were obtained from previous technology assessments (). AE disutilities were applied once at the start of the model’s time horizon.

Resource utilization and costs

Drug acquisition

The wholesale acquisition cost prices of the interventions were obtained from Analysource (). The duration of pembrolizumab and BV treatment was modeled using occupancy of the PF health state, since time on treatment (ToT) data were not available from SG035-003 for BV, and ad hoc analysis showed a minimal difference between the observed PFS and ToT data from KEYNOTE-087. The use of ToT to model treatment acquisition costs was tested in the scenario analysis. The base case analysis assumed full dosage; no adjustments were made for dose intensity.

The majority of chemotherapies, including gemcitabine, can be dispensed using a combination of different vial sizes to minimize vial wastage. With maximum dose limits and the need to consider the optimal vial mix to minimize drug costs, an optimal vial calculator was used within the base case analysis. This calculator estimated the optimal mix of vials required across the weight and body surface area following the log-normal distribution of the modeled population. Vial sharing was not considered in the base case. This information was aggregated into a single estimate of the numbers of each vial size needed to minimize waste for each therapy.

Drug administration

For the base case analysis, administration costs were set at $279.30 (CPT code 96413) for the first hour and $53.20 per hour after the first hour (CPT code 96415), applied according to the product label/dosage source (). This corresponds to the cost of intravenous administration in an outpatient setting. The costs of treatment-specific monitoring were excluded.

Disease management

Disease management costs (per patient per month) for outpatient and inpatient care (excluding the cost of medication) were sourced from a Truven database analysis of all-cause resource usage in patients during and after treatment with BV ()Citation36. Terminal care costs were not included to avoid potential double counting with disease management costs.

Adverse event costs

The costs of AEs were applied once at the start of the model’s time horizon, as it was assumed that AEs would occur within the first year of treatment. The unit costs for AEs were obtained from the 2014 HCUPnet - Hospital Inpatient National StatisticsCitation37 and adjusted to 2017 USD. As all-cause progression-free costs included no inpatient costs, the potential for double-counting adverse event cost was not a cause for concern.

Subsequent treatment costs

Costs of subsequent treatment were included in the analysis ().

Sensitivity analysis

Uncertainty surrounding the base case results was evaluated using deterministic sensitivity analysis (DSA), probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA), and scenario analyses. The DSA comprised one-way sensitivity analyses to assess the impact of changing key parameters on the incremental costs and QALYs. The PSA was performed with 10,000 simulations. Scenario analyses examined the effect of varying a variety of model parameters on costs and outcomes (the scenarios considered are presented in ).

Table 3. Scenario analysis of incremental costs and QALYs for pembrolizumab vs BV.

Results

Base case analysis

Pembrolizumab was more effective and less costly than BV and, therefore, dominated BV over a 20-year time horizon in the base case analysis. Treatment with pembrolizumab was predicted to yield an additional 0.574 LYs and an incremental gain of 0.500 QALYs compared with BV ( Treatment with pembrolizumab was also cost-saving, with an incremental cost of –$63,278 compared with BV.

Table 4. Costs and outcomes for treatment with pembrolizumab or BV.

For both treatments, drug acquisition costs accounted for the largest share of the total costs (pembrolizumab: 54%, BV: 63%). Drug acquisition costs were higher for BV than pembrolizumab because of the differences in total drug cost per cycle. AE costs were higher for BV compared with pembrolizumab, a consequence of the high rates of neutropenia, peripheral sensory neuropathy, thrombocytopenia, and anemia. The PF health state costs were higher for pembrolizumab due to the longer time spent by patients in the PF health state compared with BV. This increase in time spent in the PF health state for pembrolizumab was also the main driver for the QALY gain.

Deterministic sensitivity analysis

As shown in , factors that impacted on drug acquisition costs had the greatest impact on incremental costs. For example, variation in the population-level body weight assumptions had a large impact on the weight-based dose and costs of BV, but had no influence on costs for fixed dosing of pembrolizumab. Despite testing a lower bound body weight of 60.91 kg in the DSA, BV was still associated with higher total costs compared with pembrolizumab. Other drivers included PPS and the PFS HR. For incremental QALYs, the main drivers were PPS, the utility values applied in the PF state for both treatments, and the PFS HR.

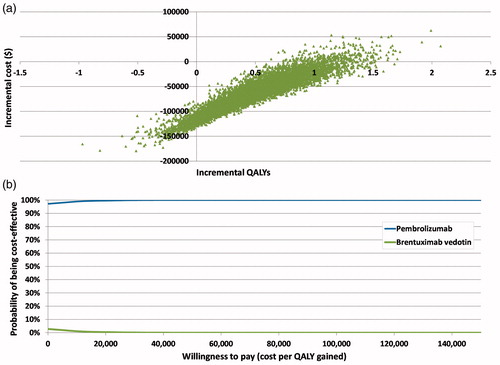

Probabilistic sensitivity analysis

The cost-effectiveness plane with 10,000 PSA simulations shows that the majority of iterations lay in the southeast quadrant where pembrolizumab was dominant over BV, with lower total costs and higher QALYs (). Pembrolizumab was associated with a mean incremental cost saving of $64,719 and mean QALY gain of 0.487 vs BV. Pembrolizumab had the greater probability of being cost-effective at all willingness-to-pay thresholds. At a willingness-to-pay threshold of $20,000 per QALY, pembrolizumab has a 99.6% probability of being cost-effective compared with BV ().

Scenario analysis

Pembrolizumab dominated BV in all scenarios tested (). The greatest impact on incremental costs was observed with the assumption of vial sharing, which reduced the costs of BV and, hence, cost savings associated with pembrolizumab by 61% ($24,857) compared with the base case ($63,278). Similarly, the greatest reduction in incremental QALYs (base case 0.500) associated with pembrolizumab occurred when the PFS HR was set to 1 (no difference between treatments) beyond 24 months, which reduced the QALY gain by 30% (0.352). PFS assessment by investigator report also reduced the QALY gain by 24% (0.379). Furthermore, changing the PFS survival function from log-normal to generalized gamma distribution resulted in the greatest increase in incremental QALYs (0.925).

Discussion

Pembrolizumab presents an alternative therapy option to BV for BV-naïve patients with RRcHL who have failed ASCT. The model predicts that mean survival would increase from an estimated 46.9 months with BV to an estimated 54.9 months with pembrolizumab. In this cost-effectiveness analysis, pembrolizumab was a dominant treatment strategy compared with BV due to a QALY gain (0.500) and lower costs ($63,278). The QALY gain was attributed to increased time spent in the PF state for the pembrolizumab-treated cohort, while cost savings vs BV were primarily driven by the difference in acquisition cost between treatments, despite a higher maximum number of cycles received with pembrolizumab (pembrolizumab: $9,026 per cycle, maximum 35 cycles; BV: $22,145 per cycle, maximum 16 cycles).

Broadly, the results of the analysis represent the extrapolation of outcomes for KEYNOTE-087. Through sensitivity analysis, we demonstrate that the results are insensitive to variation in key input parameters, indicating that our conclusions are generalizable to clinical practice, where outcome, cost, and quality-of-life parameters may differ to KEYNOTE-087.

The use of a naive ITC to generate a PFS HR for BV vs pembrolizumab is a potential source of bias in the study. In combining data from KEYNOTE-087 and SG035-003, no adjustment was made for baseline factors; therefore, any difference in outcomes across studies may have been partly due to differences in prognostic factors and effect modifiers between the study populations as opposed to the effect of drug. However, the baseline characteristics of the two trials were considered sufficiently comparable to justify the use of the naïve treatment comparison. The baseline characteristics that appeared to differ across study populations included prior use of radiation therapy (KEYNOTE-087, 40%; SG035-003, 66%) and the proportion of patients with refractory disease (KEYNOTE-087, 32%; SG035-003, 42%). Furthermore, previous BV therapy prior to ASCT was not allowed in SG035-003, but was permitted in Cohort 3 from KEYNOTE-087.

An additional assumption related to the model structure was that of a weekly PPS rate across treatment arms in the PD health state. The assumption of equivalence was considered reasonable, as it was not possible to estimate any difference in survival after disease progression, due to the lack of deaths currently observed in KEYNOTE-087, or account for the potential sequential use of pembrolizumab and BV given the dearth of relevant clinical dataCitation7. This lack of evidence on the sequential use leads to the scope of the analysis focusing on a head-to-head comparison of pembrolizumab and BV alone and determined that subsequent treatment costs were also applied equally in both arms. When this assumption was tested in sensitivity analysis by increasing the weekly rate of BV PPS to 99.47% (equivalent to ∼7 months gain for BV post-progression compared to pembrolizumab), pembrolizumab remained dominant.

A number of assumptions were made with regard to cost inputs for treatment and disease management, many of which were tested in scenario analyses. The base case analysis assumed drug wastage for BV, but incorporated an algorithm to optimize the number of vials needed based on the distribution of weight in the cohort. When the assumption of BV vial sharing (no wastage) was tested, pembrolizumab remained dominant vs BV.

The generalizability of this study outside the US and to individual centers is conditional on the goal of therapy. Following the failure of ASCT, the goal within US clinical practice is not to achieve responses to then treat with an allogeneic stem cell transplantation (“bridging therapy”)Citation38, but to continue targeted therapy with the aim of achieving long-term remission in some patientsCitation30 without the high treatment related mortality associated with allogeneic stem cell transplantation, even with reduced-intensity conditioningCitation39. Therefore, the costs and outcomes of allogenic stem cell transplantation were not considered within this cost-effectiveness analysis. Given the fixed PPS, there was no allowance for survival gains following allogeneic stem cell transplantation. In the two multi-national trials supporting this economic model, there was a higher proportion of allogenic stem transplantation within the BV trial (3% [n = 2/60] vs 8% [n = 8/102]) than KEYNOTE-087Citation22,Citation29; however, this proportion may have been protocol driven, as the trial was not designed to “bridge” to allogeneic stem cell transplant. Therefore, with the rates observed in the trials, including only the cost of stem cell transplantation costs, would have biased the results in favor of pembrolizumab.

A number of the limitations outlined relate to the absence of randomized controlled clinical trials in RRcHL, and the subsequent need to compare results from single arm studies to derive comparative efficacy. These comparisons contribute to uncertainty, as differences in outcomes between studies may not be fully attributed to drug effect and could be partly due to differences in population characteristics. The completion of the KEYNOTE-204 study, an ongoing confirmatory Phase III head-to-head study of pembrolizumab vs BV, will help address this uncertainty by providing evidence of drug effect with adequate control for population characteristics.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the study demonstrates that pembrolizumab is a cost-effective treatment option compared with BV for patients with RRcHL in the US. It is predicted that the clinical benefit of pembrolizumab in terms of an enhanced mean PFS results in survival gains with an estimated cost saving of $63,278 vs BV. In a therapy area with low survival and limited treatment options, providing pembrolizumab to RRcHL patients following ASCT may offer a cost-effective therapy with potential long-term PFS that will likely also benefit US payers.

Transparency

Declaration of financial/other relationships

EW, AB, and RHB are employees of Merck & Co., Inc., the sponsor of this study and manuscript; SL and RH provided advisory and consultancy services paid for by Merck & Co., Inc. A peer reviewer on this manuscript discloses receipt of research funding from Takeda and BMS. The remaining peer reviewers have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kate C. Young, Jessica R. May, Kiran Davé, and Nicholas Rusbridge of PAREXEL for editorial support during the preparation of this manuscript, and Sam Keeping of Precision Health Economics for conducting the indirect comparison.

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Cancer Society. Lymphoma. Atlanta, Georgia: ACS; 2015; Available at: http://www.cancer.org/cancer/hodgkindisease/detailedguide/hodgkin-disease-what-is-hodgkin-disease [Last accessed November 7, 2017]

- Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, et al. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN. Int J Cancer 2010;127:2893-917

- Jemel A, Siegel R, Xu J, et al. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer 2010;60:277-300

- Meyer RM, Gospodarowicz MK, Connors JM, et al. ABVD alone versus radiation-based therapy in limited-stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2012;366:399-408

- Merli F, Luminari S, Gobbi PG, et al. Long-term results of the HD2000 trial comparing ABVD versus BEACOPP versus COPP-EBV-CAD in untreated patients with advanced Hodgkin lymphoma: a study by Fondazione Italiana Linfomi. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:1175-81

- Engert A, Diehl V, Franklin J, et al. Escalated-dose BEACOPP in the treatment of patients with advanced-stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma: 10 years of follow-up of the GHSG HD9 study. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:4548-54

- Nikolaenko L, Chen R, Herrera AF. Current strategies for salvage treatment for relapsed classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Ther Adv Hematol 2017;8:293-302

- Sweetenham JW, Carella AM, Taghipour G, et al. High-dose therapy and autologous stem-cell transplantation for adult patients with Hodgkin’s disease who do not enter remission after induction chemotherapy: results in 175 patients reported to the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Lymphoma Working Party. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:3101-9

- Lazarus HM, Rowlings PA, Zhang MJ, et al. Autotransplants for Hodgkin’s disease in patients never achieving remission: a report from the Autologous Blood and Marrow Transplant Registry. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:534-45

- Viviani S, Di Nicola M, Bonfante V, et al. Long-term results of high-dose chemotherapy with autologous bone marrow or peripheral stem cell transplant as first salvage treatment for relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma: a single institution experience. Leuk Lymphoma 2010;51:1251-9

- Gerrie AS, Power MM, Shepherd JD, et al. Chemoresistance can be overcome with high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem-cell transplantation for relapsed and refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Ann Oncol 2014;25:2218-23

- Lavoie JC, Connors JM, Philips GL, et al. High-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation for primary refractory or relapsed Hodgkin lymphoma: long-term outcome in the first 100 patients treated in Vancouver. Blood 2005;106:1473-8

- Chopra R, McMillan AK, Linch DC, et al. The place of high-dose BEAM therapy and autologous bone marrow transplantation in poor-risk Hodgkin’s disease. A single-center eight-year study of 155 patients. Blood 1993;81:1137-45

- Tarella C, Cuttica A, Vitolo U, et al. High-dose sequential chemotherapy and peripheral blood progenitor cell autografting in patients with refractory and/or recurrent Hodgkin lymphoma: a multicenter study of the intergruppo Italiano Linfomi showing prolonged disease free survival in patients treated at first recurrence. Cancer 2003;97:2748-59

- Schmitz N, Pfistner B, Sextro M, et al. Aggressive conventional chemotherapy compared with high-dose chemotherapy with autologous haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation for relapsed chemosensitive Hodgkin’s disease: a randomised trial. Lancet 2002;359:2065-71

- Moskowitz AJ, Perales MA, Kewalramani T, et al. Outcomes for patients who fail high dose chemoradiotherapy and autologous stem cell rescue for relapsed and primary refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Br J Haematol 2009;146:158-63

- Sureda A, Constans M, Iriondo A, et al. Prognostic factors affecting long-term outcome after stem cell transplantation in Hodgkin’s lymphoma autografted after a first relapse. Ann Oncol 2005;16:625-33

- Kewalramani T, Nimer SD, Zelenetz AD, et al. Progressive disease following autologous transplantation in patients with chemosensitive relapsed or primary refractory Hodgkin’s disease or aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant 2003;32:673-9

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Pembrolizumab (KEYTRUDA) for classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Washington, D.C.: US FDA; 2017. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/InformationOnDrugs/ApprovedDrugs/ucm546893.htm [Last accessed November 24, 2017]

- Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, et al. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:579-86

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. ADCETRIS: highlights of prescribing information. Washington, D.C.: US FDA; 2017. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/125388_S056S078lbl.pdf [Last accessed November 8, 2017]

- Cheah CY, Chihara D, Horowitz S, et al. Patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma experiencing disease progression after treatment with brentuximab vedotin have poor outcomes. Ann Oncol 2016;27:1317-23

- National Center for Health Statistics. Life Tables. Hyattsville, MD: NCHS; 2014. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/life_tables.htm [Last accessed November 7, 2017]

- Weinstein MC, Siegel JE, Gold MR, et al. Recommendations of the panel on cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. JAMA 1996;276:1253-8

- Phillippo DM, Ades AE, Dias S, et al. NICE DSU technical support document 18: methods for population-adjusted indirect comparisons in submission to NICE. Sheffield, UK: NICE; 2016. Available at: http://www.nicedsu.org.uk [Last accessed November 7, 2017]

- Merck, KEYNOTE-087 CSR. Kenilworth, NJ; Data on file; 2016

- Younes A, Gopal AK, Smith SE, et al. Results of a pivotal phase II study of brentuximab vedotin for patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:2183-9

- National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Lymphoma (Hodgkin's, CD30-positive) - brentuximab vedotin [ID722]. London, UK: NICE; 2016. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/indevelopment/gid-tag467

- Merck, Kenilworth, NJ; Data on file. 2016

- Chen R, Gopal AK, Smith SE, et al. Five-year survival and durability results of brentuximab vedotin in patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 2016;128:1562-6

- Shao C, Liu J, Zhou W, et al. Utilization patterns and resource use in relapse/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma (rrHL) patients treated with brentuximab vedotin (BV). Blood 2016;128:2377

- Dolan P. Modeling valuations for EuroQol health states. Med Care 1997;35:1095-108

- Shaw JW, Johnson JA, Coons SJ. US valuation of the EQ-5D health states: development and testing of the D1 valuation model. Med Care 2005;43:203-20

- Greiner W, Weijnen T, Nieuwenhuizen M, et al. A single European currency for EQ-5D health states. Results from a six-country study. Eur J Health Econ 2003;4:222-31

- Swinburn P, Shingler S, Acaster S, et al. Health utilities in relation to treatment response and adverse events in relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma and systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma 2015;56:1839-45

- Szabo SM, Hirji I, Johnston KM, et al. Treatment patterns and costs of care for patients with relapsed and refractory Hodgkin lymphoma treated with brentuximab vedotin in the United States: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS One 2017;12:e0180261

- National Inpatient Sample 2017, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Kenilworth, NJ: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2017.

- Merck, US Market Research. Kenilworth, NJ; Data on file. 2017

- Rashidi A, Ebadi M, Cashen AF. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in Hodgkin lymphoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bone Marrow Transplant 2016;51:521-8

- Bartlett NL, Niedzwiecki D, Johnson JL, et al. Gemcitabine, vinorelbine, and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (GVD), a salvage regimen in relapsed Hodgkin's lymphoma: CALGB 59804. Ann Oncol 2007;18:1071-9

- Shang EY, Solimando DA Jr, Waddell JA. Gemcitabine and vinorelbine (GemVin) regimen. Hosp Pharm 2014;49:508-16

- Moskowitz AJ, Hamlin PA Jr, Perales MA, et al. Phase II study of bendamustine in relapsed and refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:456-60

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. GEMZAR (gemcitabine for injection): Highlights of prescribing information. Washington, D.C.: US FDA; 2017. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/020509s077lbl.pdf [Last accessed November 17, 2017]

- Nafees B, Stafford M, Gavriel S, et al. Health state utilities for non small cell lung cancer. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2008;6:84

- Tolley K, Goad C, Yi Y, et al. Utility elicitation study in the UK general public for late-stage chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Eur J Health Econ 2013;14:749-59

- National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Paclitaxel as albumin-boundnanoparticles with gemcitabine for untreated metastatic pancreatic cancer. London, UK: NICE; 2017. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta476/resources/paclitaxel-as-albuminbound-nanoparticles-with-gemcitabine-for-untreated-metastatic-pancreatic-cancer-pdf-82604969382085 [Last accessed November 7, 2017]

- National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Pixantrone monotherapy for treating multiply relapsed or refractory aggressive non-Hodgkin’s B-cell lymphoma. London, UK: NICE; 2014. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta306/resources/pixantrone-monotherapy-for-treating-multiply-relapsed-or-refractory-aggressive-nonhodgkins-bcell-lymphoma-pdf-82602369336517 [Last accessed November 7, 2017]

- Best JH, Garrison LP, Hollingworth W, et al. Preference values associated with stage III colon cancer and adjuvant chemotherapy. Qual Life Res 2010;19:391-400

- Beusterien KM, Davies J, Leach M, et al. Population preference values for treatment outcomes in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a cross-sectional utility study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010;8:50