Abstract

Aim: To characterize treatment patterns of psoriasis patients in a large US managed care database.

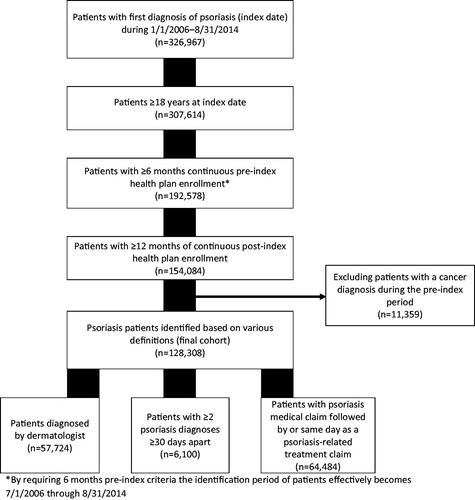

Materials and methods: Adults with newly-diagnosed psoriasis were identified from July 3, 2006–August 31, 2014. Patients had continuous enrollment with medical and pharmacy benefits for ≥6 months prior to and ≥1 year following the index date. The index date was the point at which any of the following inclusion criteria were satisfied: first psoriasis diagnosis by a dermatologist, ≥ 2 psoriasis diagnoses ≥30 days apart, or a diagnosis of psoriasis followed by a claim for psoriasis therapy. Of primary interest was to measure and describe the following psoriasis treatment patterns: utilization rates, time to treatment discontinuation, and lines of therapy for various therapeutic classes of pharmacologic therapies.

Results: From the 128,308 patients identified, 53% were female, mean ± SD age was 50 ± 16 years, with median 3 years follow-up. Topicals were received by 86% of patients, non-biologic systemics by 13%, biologics by 6%, phototherapy by 5%, and 13% received no psoriasis-related medication. Median time from index to first treatment was 0 days for topical, 6 months for non-biologic systemic, and 6 months for biologic. Of those treated, first-line therapies included topical (95%), non-biologic systemic (4%), and biologic (2%). For those with second-line treatment, non-biologic systemic (71%) and biologic (30%) therapies were more common. The most common treatment pattern was topicals only (83%), while all other patterns comprised <5% of the treatment patterns observed.

Limitations: Like other observational studies, limitations to consider when interpreting results include the 6-month pre-index period of no psoriasis or the psoriasis medication claim may not perfectly select only incident user of psoriasis medications, claims-based algorithms may not accurately represent true treatment patterns, absence of over-the-counter medications data, and having no trend analyses over time or between groups.

Conclusions: While the majority of patients with psoriasis initiated a pharmacological therapy, a significant portion did not have a claim for any psoriasis medication. Topical treatments are the most commonly used treatments for psoriasis. Non-biologic systemic and biologic therapies were rarely used first line, but became more common in later lines of treatment.

Introduction

Approximately 3.1% (6.7 million) of adults aged 20 years and older in the US have some form of psoriasisCitation1, a chronic inflammatory disease associated with psoriatic arthritisCitation2,Citation3. Skin manifestations caused by psoriasis exact considerable psychosocial stress on patients, including diminished self-esteem, self-image, and perceptions of well-beingCitation4. Furthermore, psoriasis imposes substantial economic burdenCitation5. The US annual economic burden, including direct, indirect, medical comorbidity, and intangible costs, is estimated at ∼ $112 billion in 2013 dollarsCitation6–8.

Guideline-indicated therapeutic options include topical therapiesCitation9, phototherapyCitation10, and systemic therapiesCitation11 which encompass both oral treatments and injectable biologicsCitation12. An estimated 80% of patients with psoriasis have mild-to-moderate forms of psoriasis, and can be treated solely with topical agents such as corticosteroids and vitamin D analogsCitation13. Phototherapy and systemic agents are recommended as first-line treatments for patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis, where the extent of disease makes topical treatment of all lesions impracticalCitation9.

A number of treatments for moderate-to-severe psoriasis have entered the market over the course of the past several yearsCitation8. Better penetrating and newer topical treatments have helped many patients with psoriasis, and the introduction of safe and effective biologics have revolutionized the management of moderate-to-severe psoriasis. Despite the development of new treatments, psoriasis patients remain under-treated, and many patients may feel frustratedCitation14,Citation15.

While prior studies have examined treatment patterns for patients with psoriasis, they tended to focus on specific treatmentsCitation16,Citation17 or patient populations outside of the USCitation17. The primary objective of this study was to examine and characterize treatment patterns and the sequence of treatment classes (topical therapy, phototherapy, non-biologic systemic treatments, and biologic treatments) of newly-diagnosed psoriasis patients within a large, nationally representative US managed care database. Persistence to treatments in each line of therapy was also reported.

Methods

Study design and data sources

This observational study employed a retrospective cohort design that queried longitudinal medical and pharmacy claims data from the HealthCore Integrated Research Database (HIRDSM) between July 3, 2006 to August 31, 2014. The claims data from the HIRD are derived from more than 40 million enrollees in 14 commercial and Medicare (Medicare Advantage or Medicare Supplemental plus Part D) insurance plans representing all US census regions. All data were anonymized. Investigational Review Board (IRB) informed consent requirements were waived for this non-experimental study, which conformed with research exception provisions of the Privacy Rule, 45 CFR 164.514(e).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To distinguish newly-diagnosed from existing psoriasis patients, enrollees had a 6-month washout period of no psoriasis diagnostic code nor psoriasis therapy from start of plan enrollment. Patients had to meet any one of the following inclusion criteria: at least one medical claim with a diagnostic code for psoriasis (ICD-9-CM 696.1x) by a dermatologist, at least two claims with codes for psoriasis on separate days at least 30 days apart, or a diagnosis of psoriasis followed by a claim for topical, phototherapy, or systemic psoriasis medication (see the Appendix for full list of medications and codes) in the following year. The index date was defined as the earliest date at which a patient met the inclusion criteria for psoriasis. Included patients were at least 18 years old on the index date, and had continuous enrollment with medical and pharmacy benefits for at least 6 months prior to and at least 1 year following the index date. Hence, the study observation period was from January 1, 2006 to August 31, 2015. Patients who had at least one claim with a cancer diagnosis (ICD-9 code 140.xx–209.3x, 230.xx–234.xx) during the 6-month pre-index period were excluded from the study because they were likely to be prescribed some medications of interest for oncologic-related reasons, for example non-biologic systemics: methotrexate, cyclosporine, hydroxyurea, mycophenolate, tacrolimus, and because they would be immunosuppressed, resulting in multiple complications affecting their treatment patterns ().

Treatment pattern definitions and methodologies

The treatment classes of interest in this study were topicals, phototherapy, non-biologic systemic treatments, and biologics. Up to four lines of treatment were identified for each individual. Treatment characteristics were captured from initiation of each treatment line through discontinuation of the current treatment regimen, switching treatment, or adding a new therapy. Discontinuing therapy was defined as having no claim of the current treatment for 90 days after the date the previous therapy claim supplied would have been completed. Among patients who discontinued treatments, the discontinuation date was defined as the last medication claim date plus the days supplied for that claim. A treatment switch was defined as a patient filling a treatment class that was different from any treatment class in their current or most recent regimen without continuing on the original therapy; discontinuing a medication and then restarting the same treatment was not classified as a switch. Add-on therapy was defined as filling an additional medication class while continuing therapy of another medication class. Up to three treatment changes (adding or switching) were captured, resulting in up to the first four lines of therapy being captured.

Other variables of interest

Age, sex, geographic region, and health plan type as of the index date were captured. Individual comorbidities, the Quan-Charlson Comorbidity Index (QCI), and antibiotic medication use during the 6-month pre-index period were reported. Diagnosing physician specialty was also captured; if physician specialty was not available on the index date, the closest claim to the index date with a diagnosis of psoriasis was used to categorize the diagnosing physician.

Statistical analysis

This retrospective cohort study was descriptive in nature and analyzed treatment patterns within the entire cohort of psoriasis patients without a comparison group. Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, medians, interquartile ranges [IQR], frequencies, and percentages) were calculated for each outcome of interest. All analyses were conducted using SAS Enterprise Guide v7.1 (Cary, NC).

Results

Demographics and baseline data

The study population consisted of 128,308 patients whose mean ± SD age was 50 ± 16 years, and 53% were female. Most patients (57%) were initially diagnosed or treated by a dermatologist. Dyslipidemia, hypertension, mental illnesses, and dermatitis were some of the most common comorbid conditions (> 10% each, ).

Table 1. Baseline patient characteristics (n = 128,308).

Treatment patterns

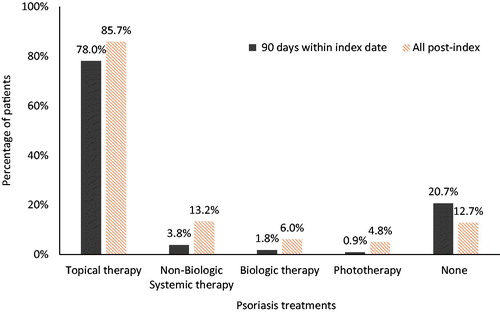

Patients were followed for a median of 3 years following their initial psoriasis diagnosis (). Approximately 13% of patients did not receive any of the specified psoriasis-related treatments (). Overall, the most prevalent treatments were topical therapy (85.7%). Non-biologic systemic therapy (13.2%), biologic therapy (6.0%), and phototherapy (4.8%) were less common.

Figure 2 First line medication use within 90 days of the index date (solid bars) and at any time during the post-index period (striped bars) (n = 128,308).

Table 2. Follow-up times and time to treatment among individuals newly diagnosed with psoriasis (n = 128,308).

Patients filling a topical at any point during follow-up did so within a median (IQR) of 0 (1) days after index date, indicating that more than half of patients with topical therapy filled the therapy on the index date. The median time to first fill of non-biologic systemic treatments was 181 (510) days and for biologic therapy it was 196 (578) days ().

Treatment sequences

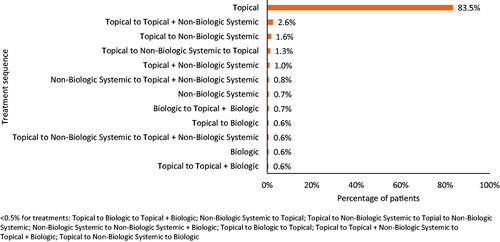

In the sub-group of patients who received treatment (n = 111,962), 83.5% received only topical therapy for the duration of follow-up (), 2.6% started with a topical and later added a non-biologic systemic, and 1.6% initiated topical therapy and subsequently switched to non-biologic systemic therapy. Switching from topical to non-biologic systemic and back to topical occurred in 1.3% of patients, while 1.0% of patients started their treatments with a combination of topical and non-biologic systemic therapies. Other observed sequences, including switching or adding biologics, accounted for less than 1% of the treatment patterns observed.

Figure 3 Top treatment sequences across all lines of treatment among treated individuals with psoriasis (n = 111,962). Drugs taken in combination during the same line of therapy are depicted via the “+” symbol, and different lines of therapy are separated by the word “to”. For example “Topical to Topical + Systemic” indicates a regimen of first line topical monotherapy to a second line therapy of topical therapy and the addition of systemic therapy.

Characteristics by line of therapy

Switching or adding on therapy to first-line treatment was observed in 11.0% of topical users, 56.1% of non-biologic systemic users, and 72.5% of first-line biologic users (). Under first-line treatment the proportion of patients discontinuing therapy was high among those initiating topicals (69.7% discontinuation rate), followed by non-biologic systemic (26.8%) and biologic (8.1%) users. The longest persistence observed during first-line treatment was with topicals, with a mean ± SD of 658 ± 712 days followed by non-biologic systemics with 469 ± 570 days and biologic with 431 ± 486 days.

Table 3. Treatment line characteristics based on first treatment received in patients newly-diagnosed with psoriasis and treated with a psoriasis therapy (n = 111,962).

Of all patients receiving treatment, 14% (n = 15,841) moved to a second-line therapy, 6.1% (n = 6,808) further moved to a third-line therapy, and 1.9% (n = 2,090) moved to a fourth-line therapy. Non-biologic systemics were the most common treatment class among second-line therapies, observed in 70.6% of patients. Diminishing numbers of patients moved on to each subsequent line of therapy in the observed period. Biologics became progressively more common with each additional line of therapy, increasing from 2.2% of first-line therapies, to 30.0% of second-line, 43.6% of third-line, and 55.8% of fourth-line therapies. The most common treatment change among those who moved from first- to second-line therapy was switching from topical to non-biologic systemic (33.0%). Among those who moved from second- to third-line, the most common treatment change was a switch from non-biologic systemic to topical (28.4%), and for those who moved from third- to fourth-line, the most common change was switching from topical to non-biologic systemic (14.0%).

Discussion

This study provides insights into the treatment patterns of newly-diagnosed psoriasis patients within a large population of commercially insured enrollees. Although patients were followed for a median of 3 years, ∼ 13 of every 100 patients had no claim for a prescription treatment during that period. Of the patients who received prescription therapy, the vast majority received topical agents, followed by a much smaller proportion who received non-biologic systemic therapies, and an even smaller proportion who received biologic agents. These findings are consistent with prior research reporting that the three most common psoriasis medications were topical corticosteroids (accounting for 81% of all psoriasis treatmentCitation18) and another study which reported the large majority of first line use is with topical therapies and over the counter medications, while biologic and non-biologic systemic therapies become more common during the third and fourth linesCitation19. These observations are likely driven by clinical guidelinesCitation9–12 and formulary restrictionsCitation20.

Overall, more than 85% of patients received topical therapy only (72.8%) or either were not prescribed or did not fill a prescription for therapy at all (12.7%). While more intensive systemic therapies are used for moderate-to-severe psoriasis, topical therapies may be sufficient for patients with limited diseaseCitation21. Thus, the relatively low use of biologic and other systemic therapies may correlate with the high proportion of psoriasis patients without extensive disease for which topical therapies would be impractical. However, because disease severity was not available in the claims data, we were not able to measure treatment patterns separately by the level of disease severityCitation9,Citation11. While our study was not designed to examine treatments against disease severity, a study by Patel et al.Citation22 shows some broad similarities between our study and how dermatologists manage psoriasis. In a study cohort of 895 patients, the authors noted that dermatologists prescribed topical therapy to 86% of patients, non-biologic systemics to 14%, and biologics to 19%; patients with severe psoriasis had a much higher rate of biologic use (41%) compared with those with moderate disease (19%)Citation22. While we found similar rates of topical and non-biologic systemic use, the use of biologics was much lower in our study, likely indicative of the broad representativeness of the large, commercially-insured patient population used in our study, as well as our inclusion of only incident psoriasis patients compared with the prevalent population studied by Patel et al.

Although these results provide insights on this patient population, there are general study limitations, which should be considered while interpreting the results. The study was designed to identify new psoriasis patients employing a 6-month clean period (no psoriasis or psoriasis medication claim prior to the index claim); however, this may not necessarily capture true incident use of psoriasis medicationsCitation8. Furthermore, reliance on a claims-based algorithm might not accurately represent the true treatment patterns, as an analysis of prescription fills do not account for prescription-free distribution of medications (e.g. samples) to patients, nor does the presence of such fills certify that medication was taken as prescribed. In terms of the former point, it may be reasonable to assess the treatment patterns presented in this study in light of the provision of such free medications, depending on how strongly the reader believes such behaviour is prevalent and substantial in volume to the patient. Additionally, in class switching—such as going from one topical to another—was not captured as a treatment change. Claims databases are not equipped to capture medications acquired over-the-counter, such as low dose steroid creams, or as provider samples. Also, variations in the treatment patterns observed in this study are likely to be impacted by the severity of the psoriatic disease, and such severity measures are not available or well defined through the use of an administrative claims database alone. Future studies evaluating real-world treatment patterns in psoriasis would benefit from integrating this clinical perspective, as well as treatment of common comorbidities. Finally, the outcomes of this study are based on data from commercially insured and Medicare (Medicare Advantage and Medicare Supplemental plus Part D) members insured by 14 plan-states in the US between January 1, 2006 and August 31, 2015. Therefore, the results may not be generalizable to individuals with other types of health insurance, and represent only psoriasis treatments approved by FDA before August 31, 2015. Statistical testing or trend analyses were not performed, precluding any inferences on differences in trends over time or between groups.

Conclusions

Topical therapies were the most common treatment choice in this cohort of newly-diagnosed psoriasis patients, while a small proportion of patients received non-biologic systemic or biologic medications as first line therapy. Few patients moved beyond a single line of therapy, and treatment with biologic therapy, while uncommonly seen in first line therapy, increased as patients reached second, third, and fourth lines. Future research may build upon these findings by examining the utilization of advanced treatments of psoriasis according to the severity of the disease.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was supported by Eli Lilly and Company.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

MJM, WNM, TMM, and ABA are employees and stockholders of Eli Lilly and Company. LC was an employee of Eli Lilly and Company at the time this work was performed. DMK, KS, and RAQ are employees of HealthCore, Inc., which received funding from Eli Lilly and Company to conduct the research. SRF is an employee of The Wake Forest University School of Medicine. SRF has received research, speaking, and consulting support from Abbvie, Celgene, Janssen, Lilly, and Norvatis. One peer reviewer on this manuscript has declared working as a consultant for Novartis, Janssen, and Pfizer and as an investigator for Novartis, Janssen, Abbvie, Pfizer, Celgene, Amgen, Regeneron, and Leo Pharma. The remaining peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Previous presentation

AMCP Nexus 2016 abstract and poster.

Acknowledgments

Bernard Tulsi and Mukul Singhal, employees of HealthCore, Inc., provided writing support for this manuscript.

References

- Helmick CG, Lee-Han H, Hirsch SC, et al. Prevalence of psoriasis among adults in the U.S.: 2003–2006 and 2009–2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Am J Prev Med 2014;47:37–45

- Kurd SK, Gelfand JM. The prevalence of previously diagnosed and undiagnosed psoriasis in US adults: results from NHANES 2003–2004. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009;60:218–24

- Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014;70:512–16

- Kimball AB, Jacobson C, Weiss S, et al. The psychosocial burden of psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol 2005;6:383–92

- Feldman SR, Burudpakdee C, Gala S, et al. The economic burden of psoriasis: a systematic literature review. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2014;14:685–705

- Yeung H, Takeshita J, Mehta NN, et al. Psoriasis severity and the prevalence of major medical comorbidity: a population-based study. JAMA Dermatol 2013;149:1173–9

- Brezinski EA, Dhillon JS, Armstrong AW. Economic burden of psoriasis in the United States: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol 2015;151:651–8

- Takeshita J, Gelfand JM, Li P, et al. Psoriasis in the US medicare population: prevalence, treatment, and factors associated with biologic use. J Invest Dermatol 2015;135:2955–63

- Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Section 3. Guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009;60:643–59

- Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: Section 5. Guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with phototherapy and photochemotherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol 2010;62:114–35

- Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 4. Guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with traditional systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009;61:451–85

- Menter A, Gottlieb A, Feldman SR, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: Section 1. Overview of psoriasis and guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008;58:826–50

- Moghadam-Kia S, Werth VP. Prevention and treatment of systemic glucocorticoid side effects. Int J Dermatol 2010;49:239–48

- Armstrong AW, Robertson AD, Wu J, et al. Undertreatment, treatment trends, and treatment dissatisfaction among patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in the United States: findings from the National Psoriasis Foundation surveys, 2003–2011. JAMA Dermatol 2013;149:1180–5

- Horn EJ, Fox KM, Patel V, et al. Are patients with psoriasis undertreated? Results of National Psoriasis Foundation survey. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007;57:957–62

- Bonafede M, Johnson BH, Fox KM, et al. Treatment patterns with etanercept and adalimumab for psoriatic diseases in a real-world setting. J Dermatolog Treat 2013;24:369–73

- Svedbom A, Dalen J, Mamolo C, et al. Treatment patterns with topicals, traditional systemics and biologics in psoriasis - a Swedish database analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2015;29:215–23

- James SM, Hill DE, Feldman SR. Costs of common psoriasis medications, 2010–2014. J Drugs Dermatol 2016;15:305–8

- DiBonaventura M, Wagner S, Waters H, et al. Treatment patterns and perceptions of treatment attributes, satisfaction and effectiveness among patients with psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol 2010;9:938–44

- Malatestinic W, Amato D, Feldman SR. Formulary decisions and the evolution of psoriasis treatment. J Clin Pathways 2015;1:43–7

- Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 6. Guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: case-based presentations and evidence-based conclusions. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011;65:137–74

- Patel V, Horn EJ, Lobosco SJ, et al. Psoriasis treatment patterns: results of a cross-sectional survey of dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008;58:964–9