Abstract

Aims: There have been no systematic literature reviews (SLRs) evaluating the identified association between outcomes (e.g. clinical, functional, adherence, societal burden) and Quality-of-Life (QoL) or Healthcare Resource Utilization (HCRU) in schizophrenia. The objective of this study was to conduct a SLR of published data on the relationship between outcomes and QoL or HCRU.

Materials and methods: Electronic searches were conducted in Embase and Medline, for articles which reported on the association between outcomes and QoL or HCRU. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to identify the most relevant articles and studies and extract their data. A summary table was developed to illustrate the strength of associations, based on p-values and correlations.

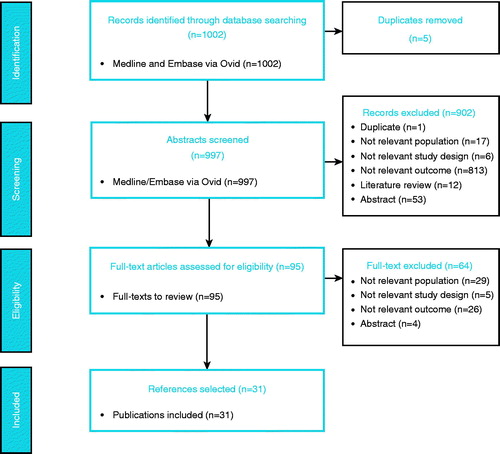

Results: One thousand and two abstracts were retrieved; five duplicates were excluded; 997 abstracts were screened and 95 references were retained for full-text screening. Thrirty-one references were included in the review. The most commonly used questionnaire, which also demonstrated the strongest associations (defined as a p < 0.0001 and/or correlation ±0.70), was the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) associated with HCRU and QoL (the SF-36, the Schizophrenia Quality-of-Life questionnaire [S-QOL-18], the Quality-of-Life Scale [QLS]). Other robust correlations included the Clinical Global Impression–Severity (CGI-S) with QoL (EQ5D), relapse with HCRU, and remission with QoL (EQ5D). Lastly, functioning (Work Rehabilitation Questionnaire [WORQ] and Personal and Social Performance Scale [PSP]) was found to be associated to QoL (QLS and Subjective Well-being under Neuroleptics Questionnaire [SWN]).

Limitations: This study included data from an 11-year period, and other instruments less frequently used may be further investigated.

Conclusions: The evidence suggests that the PANSS is the clinical outcome that currently provides the most frequent and systematic associations with HCRU and QoL endpoints in schizophrenia.

Introduction

Patients with schizophrenia present with a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations. The symptoms of schizophrenia are usually divided into “positive symptoms” and “negative symptoms”. Schizophrenia is also associated with symptoms such as cognitive and functional impairmentsCitation1. Schizophrenia is estimated to affect more than 21 million people worldwideCitation2 and ∼1.2% of Americans (3.2 million)Citation3. Schizophrenia usually persists, continuously or episodically, throughout a patient’s lifetime, with remission—a return to full premorbid functioning—being uncommon. Some individuals appear to experience a relatively stable course of disease, whereas most show a progressive worsening associated with severe disability.

The financial burden of schizophrenia relies on the need for institutionalization and the chronic use of treatments. Schizophrenia is associated with large costs for individuals and society as wellCitation4–6. Moreover, patients may not respond to treatment or even reject treatment, which ultimately entails more relapses, hospital admissions, and worsening of disease symptomsCitation7.The humanistic burden of schizophrenia must be taken into account, as it has a profound impact on a patient’s quality-of-lifeCitation8. Although it is difficult to measure accuratelyCitation9, this humanistic burden on patients and people around them appears to be worse for patients with schizophrenia than those suffering from other mental disordersCitation10. Schizophrenia is a multifactorial disease and has wide-ranging impactsCitation8, including burden on non-professional caregivers, such as familyCitation11,Citation12, lower rates of employment, marriage, and independent livingCitation13, discrimination and stigmatizationCitation14, and substance abuseCitation15. Cost-effectiveness modelsCitation16–18 have attempted to model the associations between different outcomes, yet the associations and trajectories in these models are often indirect or implicit. For example, the impact on hospitalizations due to relapses has been modeled, but not directly linked to symptoms.

Currently, there has been no systematic literature review (SLR) carried out on the study and documentation of direct associations reported between comprehensive outcomes, such as clinical measures or functioning, and Quality-of-Life (QoL) or Healthcare Resource Utilization (HRCU) in schizophrenia. In this SLR, we aim to identify direct associations—correlations or regressions—between a defined set of outcomes (e.g. symptom-related, side-effects, functioning, adherence or compliance, societal/family/caregiver burden) and HCRUor QoL, via a specific list of instruments, to ultimately obtain an overview of the evidence available directly associating these endpoints in schizophrenia.

Methods

A specific list of the outcomes and associations of interest was defined as the scope of this review and were divided into main outcomes, QoL outcomes, and HCRU outcomes. The main outcomes were comprised of clinical outcomes, side-effects, functioning, compliance/adherence and satisfaction, and societal/family/caregiver burden. For each of these outcome dimensions, a list of specific outcomes and/or instruments was defined based on the most frequently used and validated instruments. The comprehensive list of these main outcomes can be found in . QoL instruments were selected in the same manner and are listed in . HCRU outcomes were not limited, but were defined as any resource utilization or costs, such as the number of hospital visits, cost of treatments, and length of hospitalizations. When reporting the results, a distinction was made between healthcare costs, which were reported directly, and resource utilization, where no mention of the actual cost was made.

Table 1. Main outcomes.

Table 2. Quality-of-life outcomes.

A search strategy was defined to combine disease-related keywords, main outcomes, and QoL outcomes or HCRU. The full search strategy is detailed in the Supplementary materials. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined () according to the PICOS tool. Studies included were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies. Studies were excluded if the population included other psychiatric or central nervous system disorders, or if they did not report subgroup results for the schizophrenia population exclusively. Review articles and articles reporting on psychometric validation studies were excluded, as associations between outcomes are not analyzed or reported in these types of study. No geographical limits were applied on this search. The search timeframe applied was from January 2007 to January 2018.

Table 3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Searches were conducted on February 1, 2018 in Medline and EMBASE databases (via the OVID interface), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and the clinicaltrials.gov website. The titles and abstracts of retrieved studies were screened by two independent reviewers, and relevant articles were selected according to the defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any discrepancies between the two reviewers were resolved by a third, independent reviewer. References were either included as potentially relevant, included as no abstract was available, or excluded, with primary reasons for exclusion recorded. Additionally, SLRs that met all other inclusion criteria were retained, all reported references were exported, and their abstracts were obtained, which were also screened.

Once full publications were obtained, they were screened by two independent reviewers, with any discrepancies resolved by a third reviewer. Primary reasons for exclusion were recorded. The same exclusion criteria applied to abstracts; references only available in poster format were also excluded. The relevant data, from references that met inclusion criteria and were finally classified as “included” following full-text screening, were then extracted in Excel spreadsheets, with quality checks executed for all extractions.

Risk of bias was assessed for RCTs using the Cochrane risk of bias tool. To summarize and qualitatively assess the associations, the p-value or correlation was used to create a score representing the strength of the association. These scores were used to develop a table providing an overview of the strength of the association of the results identified, defined as follows: very strong (+++), strong (++), weak (+), or no significant association (–). If the p-value was given for the association, the association strength was determined on this basis, according to the following criteria: p < 0.0001 (+++); p < 0.01 (++); p < 0.05 (+); p ≥ 0.05 (–). If the p-value was not available for correlation results, the strength on the association was determined as follows: ±0.70 +++; ±0.50 ++; ±0.30 +. For cost results, the strength was reported as (++) if the difference was higher than 20% between the two groups compared in the article.

Results

The PRISMA flow diagram in presents in detail the study selection process along with exclusion reasons for each screening phase. In total, the search yielded 1,002 records. Five of these were duplicates and were excluded. Nine hundred and ninety-seven abstracts were screened. A total of 31 publications, reporting on 24 studies, were included in this review. When references were excluded due to irrelevant outcomes, this was most often because, although relevant outcomes were included as study endpoints, no association between these was studied or reported. When references were excluded due to irrelevant population, this was most often because the schizophrenia population was pooled with patients with schizoaffective disorder and/or major depressive disorder, and results were not reported separately.

Studies

Of the 24 studies included in this SLR, nine were conducted in more than one country. The highest number of studies was conducted in Germany (six studies), followed by Italy (five studies), and then by the US, France, and Spain (four studies each). More than two-thirds (22 of 31) of the included articles were published within a 5-year period between 2012 and 2017. A total of 21 (88%) out of the 24 studies reported inclusion criteria related to the schizophrenia diagnosis. Two studies relied on both the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) and the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD 10) definitions of schizophrenia to include patients. Other inclusion criteria were related to age and previous or current treatments. Twenty-one (88%) out of the 24 studies reported on non-interventional studies. Information on follow-up duration was available for 11 studies (45%). The most common lengths of follow-up were 12 and 24 months (two studies each). The duration of follow-up ranged from 12 weeks to 41.5 months. Regarding sample size, 13 (48%) of 27 articles enrolled between 100 and 500 participants, while four articles did not mention the sample size. Four studies (17%) enrolled less than 100 patients, four enrolled between 1,000 and 2,000 patients, and three studies (13%) enrolled more than 10,000 patients.

The drugs that were most frequently used by patients while participating in studies were olanzapine (four studies; 17%), followed by risperidone and quetiapine (two studies; 16%, each), ziprasidone, perphenazine, clozapine, palperidone palmitate, amisulpride, and aripiprazole (one study; 4%, each). Most studies included more than one drug. A total of 26 articles provided information on respondents’ ages.

Study population

The mean age of the study populations at inclusion ranged from 28.4–46.8 years. Most of these studies (77%) included patients whose mean age was between 33 and 40.8 years. Out of 24 studies, only threeCitation48–50 (13%) expressed clearly that both men and women were included in the samples. Out of the six articles (25%) that provided information on previous treatments, four (17%) of them mentioned the use of antipsychoticsCitation49,Citation51–53; one (4%) described the use of clozapineCitation54, and one (4%) the use of more than three psychotropic medicationsCitation55. A distinction was made between whether it was a first or second generation drug in one of the studiesCitation53. The use of antidepressants and mood stabilizers is mentioned in two studiesCitation51,Citation53 concomitantly with antipsychotics. A total of 12 studiesCitation49,Citation51–53,Citation55–61,Citation69 (50%) provided information on employment among the study population. TwoCitation57,Citation60 of these 12 studies included details about the percentage of patients employed depending on relapse status, and another studyCitation62 detailed the employment status of the patients. Out of the 24 studies, 14Citation49,Citation52–54,Citation56–58,Citation60,Citation61,Citation62–66 (58%) mentioned the duration of the disease, which ranged from 10–20 years, with a median of 11.8 years. Five studies (21%) gave information based on the sub-groups studied, including the relapse status for two of themCitation57,Citation60, the out/inpatient status for one otherCitation65, the refractory or super-refractory status for another oneCitation54, and the negative symptom status for the lastCitation62 study.

Associations

summarizes the associations determined, the strength of associations, and the articles reporting associations.

Table 4. Summary of associations, strength of associations, number of associations, and references.

Patterns in associations reported

The Positive and Negative Symptom Score (PANSS) was the scale most often used and the scale for which the highest number of associations were reported, particularly for the PANSS negative score associated with HCRU/Costs, QoL, and employment status. There is more evidence available for associations between the PANSS-negative and PANSS-positive scores individually than there is for the PANSS total score. Several strong associations were identified between the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) and QoL, but not between the CGI and HCRU. Some strong associations were identified between relapse (various definitions) and HCRU or costs, but far fewer associations were identified between relapse and QoL. Only one association was found between remission and resource utilization, one between remission and QoL, but none were found between remission and costs or remission and employment. An association was identified between functioning and HCRU, but not directly with costs themselves. Associations were identified between functioning and QoL. Only one association was reported between medication adherence and costs, and one association between medication adherence and QoL. Employment status showed associations with HCRU, costs, and QoL.

Clinical endpoints associated with HCRU

presents the associations identified between clinical endpoints and HCRU, the strength of associations, the articles reporting associations, and the study countries.

Table 5. Summary of associations between clinical outcomes and HCRU/cost.

Several strong associations were identified between the PANSS (total score and the positive and negative sub-scales) and HCRU. The PANSS general psychopathology sub-scale was associated with HCRU, but not with costs directly. No associations were available between any other clinical/symptom scales and cost or HCRU (other than those used to define relapse or remission). When looking at costs specifically, two studiesCitation62,Citation69 reported relatively strong associations between the PANSS negative and total costs as well as some other specific costs. One articleCitation67 reported very strong associations between the PANSS total score and both inpatient costs and psychiatric care total costs. Data associating the PANSS with resource use were also availableCitation59,Citation62,Citation65,Citation67,Citation71, with the most and the strongest associations with hospitalizations (duration)Citation59,Citation65. Only one articleCitation59 reported the association between change in PANSS scores over time and HCRU, with a decrease in PANSS total and PANSS positive sub-scale associated with a significant decrease in the risk of psychiatric hospitalizations. Considerable dataCitation60,Citation74,Citation77,Citation81 were also available on the association between relapse and HCRU, notably with a direct association with costs. It should be noted that a number of different definitions of relapse were used. The studies that reported the most robust associations between relapse and costCitation60,Citation69 used a definition of an increase in the CGI score or hospitalizations or inpatient admissions/hospitalizations. In studies that used the CGI without scores employed to define remission or relapse, no data was available to support the association between the CGI and HCRU. Only one studyCitation52 demonstrated an association between remission and resource utilization. Only two studiesCitation52,Citation74 that reported associations between clinical outcomes and costs or HCRU took place outside Europe and the US; the only studyCitation52 to report the link between remission and HCRU took place in Malaysia, and one studyCitation74 linking relapse to HCRU took place in Japan.

Clinical endpoints associated with QoL

presents the associations identified between clinical endpoints and QoL, the strength of associations, the articles reporting associations, and the study countries.

Table 6. Summary of associations between clinical outcomes and QoL.

The PANSS is the endpoint for which the most convincing data were available to support the link between symptoms and QoL. The Quality-of-Life Scale (QLS) was the outcome for which the most data was available, both for associations with the PANSS and with the CGI. Although the PANSS is the critical scale used to measure symptoms in this population, several different QoL instruments have been used in studies, both generic (EuroQol -5D (EQ5D), Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-36 (SF36)), and disease-specific (the Subjective Well-Being Under Neuroleptics Scale short form (SWN-K), the Quality of Life for Schizophrenics Scale (S-QOL), and the QLS). The studies using the QLS provided the highest number of strongest links between the PANSS (total, negative, positive, and general psychopathology sub-scales) and QoLCitation55,Citation58,Citation68,Citation71–73. One studyCitation78 demonstrated a very strong link between remission (defined as a score lower than 3 on the CGI for 6 months, and no hospitalizations) and the EQ5D. Strong links between relapse and the SWN-KCitation51 (relapse defined as no more than moderate severity on a set of PANSS items), and between relapse (relapse defined as no less than moderate severity on a set of PANSS items, and as hospitalization or a re-emergence of symptoms such as delusions, hallucinations, or bizarre behavior, or a thought disorder lasting 7 days or more) and the SF36 physical and mental component summary scoresCitation75 were also demonstrated. The studies demonstrating links between clinical endpoints and QoL were carried out across a diverse range of countries; these studies notably used the PANSS and were conducted in Europe, the US, Russia, Taiwan, and Brazil. Only one studyCitation53 using the CGI was carried out outside Europe, in Taiwan.

Clinical endpoints associated with employment

presents the associations identified between clinical endpoints and Employment, the strength of associations, the articles reporting associations, and the study countries.

Table 7. Summary of associations between clinical endpoints and employment status.

One studyCitation50 showed strong associations between the PANSS negative and positive sub-scales and employment status, which was carried out in Bangladesh. Another studyCitation61 also showed some associations between the PANSS total score, negative and positive sub-scales, and employment status; this study was carried out in Malaysia. A European studyCitation60 showed a significant association between relapse (defined as an increase in the CGI overall severity score or hospitalization) and employment status.

Functioning endpoints associated with HCRU, QoL, and employment status

No evidence was available for associations between functioning and costs, or between functioning and employment status. One studyCitation49 conducted in Italy demonstrated a limited association between functioning (the Personal and Social Performance Scale (PSP)) and HCRU (hospitalization), and another studyCitation53 in Taiwan showed a strong association between the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) and HCRU (a difference in the frequency of psychiatric admissions and in the number of psychiatric admissions). Regarding QoL, studies with the PSPCitation49,Citation63 showed more and stronger associations with functioning than other scales, although evidence of associations was also available with the Work Rehabilitation Questionnaire (WorQ)Citation80 and the GAFCitation58. Most of this evidence came from cross-country studies.

Treatment adherence associated with HCRU, QoL, and employment status

No studies provided evidence of associations between adherence and costs, or between adherence and employment status. Only one studyCitation69 demonstrated a weak association between the Medical Adherence Rating Scale (MARS) and the frequency of admission in France, Germany, and the UK, and one studyCitation61 demonstrated a weak association between the MARS and the S-QLS, in China.

Employment status associated with HCRU and QoL

One Japanese studyCitation77 provided evidence of a strong association between employment status and HCRU (hospitalization), and another studyCitation69 from France showed a weak association between employment and (day clinic) costs. Two studiesCitation55,Citation58, in Brazil and Italy, showed stronger associations between employment status and QoL (using the QLS).

Discussion

There is extensive literature available on the burden of schizophrenia, both regarding QoL burden on patients and their families or caregiversCitation82 and economic burdenCitation83,Citation84. However, no previous review has examined the evidence available for the association between specific clinical or functioning endpoints and QoL or HCRU endpoints. It was hypothesized that the study design (interventional or observational), population (inclusion criteria), interventions, and outcomes would be very disparate, and that a systematic review would be more relevant than a meta-analysis. These hypotheses were confirmed in our findings. Our review identified a number of associations, and the most commonly used questionnaires to measure the endpoints used in establishing these associations.

The PANSS was the most frequently used schizophrenia symptom endpoint, which provided the most substantial and highest level of evidence that negative and/or positive symptoms specifically are associated with certain HCRU and QoL endpoints. This conclusion must be interpreted with caution, as the most substantial evidence is available for this scale also because it is the most commonly used symptoms scale. The high frequency of PANSS as an outcome may be linked to its separate positive and negative symptoms scales, which mean it is more sensitive to change than other scales. The PANSS negative sub-scale seems to be of particular value in demonstrating an impact on QoL, where it was also the most commonly reported used sub-scale. The most commonly impacted HCRU endpoint associated with the PANSS was hospitalization. Associations between the PANSS and actual cost were limited, with two studiesCitation62,Citation69 failing to demonstrate a significant association. It is interesting to note that strong associations can be demonstrated between a number of QoL instruments (SWN, EQ5D, SD36, QLS, S-QOL) and other endpoints (clinical, relapse status, functioning, employment status), whereas the PANSS, and in some cases the CGI, were the only instruments measuring symptoms for which associations with other endpoints were demonstrated.

Moreover, both generic and specific QoL instruments demonstrated associations with other endpoints. ThreeCitation50,Citation57,Citation61 of the fourCitation50,Citation57,Citation60,Citation61 studies reporting associations between the PANSS or relapse and employment were carried out in Asian countries. It is likely that the environment for the employment of individuals with schizophrenia in these countries differs from that in Europe and the US. No studies from the US reported an association between the PANSS or relapse and employment.

Various definitions of relapse status were used: daycare outcomes (either completing daycare and entering employment/training, or relapse and hospitalization); inpatient admission; an increase in the CGI-overall severity score; or having had a hospitalization. Relapse seems to be strongly associated with costs, mainly when CGI scores or hospitalizations were used as the definition of relapse. However, one studyCitation69 did not define relapse. Two different definitions of remission were also used: achieving a score of 3 on the CGI -Schizophrenia scale, maintained for 6 months and without hospitalization; >60 score on the PSP. Given the varied definitions of relapse and remission used in the studies, it may be valuable to gain further understanding of the impact of the varied definitions on different outcomes.

Furthermore, no studies were identified that examined associations with incarceration, family burden, side-effects, or satisfaction. Incarceration is a known issue within the schizophrenia populationCitation85, and it is interesting to note that there have been no studies investigating the associations between symptoms and incarceration, or incarceration and HCRU. The association between schizophrenia and incarceration has been reported in other studies, but not detailed at the symptom level. There was a lack of evidence of the association between remission and HCRU and remission and QoL being studied, despite the fact that patients in remission should have improved QoL and use fewer resources. There is a clear need for evidence generation on the impact of remission on these outcomes.

Limitations

We limited our search to articles published between 2007 and 2018 and may, therefore, have missed relevant data from studies published earlier than this. However, changes in healthcare systems, schizophrenia management, availability of treatment, and scales no longer used limit the potential consequences of this time limitation. When screening abstracts, those that did not mention the associations of interest were excluded. Yet, it may be that the articles reported associations, while the abstracts made no mention of these associations. Specific instruments were listed for our search strategy and inclusion criteria and were included in the protocol. It is possible that associations using other instruments were published, but excluded from this search. We used the p-value to provide a summary of the assessment. While the p-value is linked to the strength, it is only one element, and the strength of the association as measured by the correlation or regression coefficient is also needed for full assessment. As for any endpoint, the more an instrument is used, the more data is available to provide evidence for the instrument and its ability to establish solid endpoints and strong associations. Conclusions regarding the ability of certain instruments to demonstrate stronger associations should be made with caution, as some instruments were used far more frequently than others.

Conclusions

The PANSS was the endpoint applied most often in studies, and the scale for which the highest number of associations were linked to HCRU (duration of hospitalizations and costs showing the strongest associations) and QoL (particularly strong associations using the QLS). The CGI was also associated with QoL (particularly using the EQ5D), but no data were identified demonstrating associations with HCRU. Other clinical outcomes such as relapse seem to be strongly associated with costs and HCRU, but remission had limited associations with HCRU and QoL.

Other types of outcomes and their association with HCRU and QoL also revealed some interesting insights. Functioning outcomes as measured by the PSP and GAF seem to be associated with HCRU and QoL, with particularly strong associations identified between the PSP and QoL. There was limited evidence of an association between adherence (MARS) and costs, and adherence and QoL (one study per outcome). Employment status also seems to be associated with HCRU, costs, and QoL. However, no associations with HCRU or QoL were identified for incarceration, family burden, side-effects, or satisfaction.

The direct associations and correlations of HCRU or QoL with clinical, social, adherence, and functional outcomes identified in this study will be further explored using quantitative methods in an early endpoint model to predict changes on health economic outcomes based on changes in the PANSS scores.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Lundbeck.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

Creativ-Ceutical received professional fees from Lundbeck for the conduct of this study. NG, CF, and AJ are employed by Creativ-Ceutical. JW, SK and EL are employed by Lundbeck. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Previous presentations

Part of this study was presented as a poster at ISPOR Barcelona, November 10–14, 2018.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Magali Desroches for her work on screening, data extraction, and preparing the manuscript, and to Monique Dabbous for her support in preparing the manuscript.

References

- Reichenberg A, Harvey PD, Bowie CR, et al. Neuropsychological function and dysfunction in schizophrenia and psychotic affective disorders. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:1022–1029.

- Martin P, Caci H, Azorin JM, et al. [A new patient focused scale for measuring quality of life in schizophrenic patients: the Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale (SOL)]. Encephale. 2005;31:559–566.

- Nemade R, Dombeck M. Schizophrenia symptoms, patterns, statistics and patters 2009 [updated 2017 Dec 19]. Available from: www.mentalhelp.net/poc/view_doc.php?type=doc&id=8805

- Abouzaid S, Jutkowitz E, Foley KA, et al. Economic impact of prior authorization policies for atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia. Popul Health Manag. 2010;13:247–254.

- Willis M, Svensson M, Lothgren M, et al. The impact on schizophrenia-related hospital utilization and costs of switching to long-acting risperidone injections in Sweden. Eur J Health Econ. 2010;11:585–594.

- de Silva J, Hanwella R, de Silva VA. Direct and indirect cost of schizophrenia in outpatients treated in a tertiary care psychiatry unit. Ceylon Med J. 2012;57:14–18.

- Voruganti LN, Awad AG, Oyewumi LK, et al. Assessing health utilities in schizophrenia. A feasibility study. Pharmacoeconomics. 2000;17:273–286.

- Millier A, Schmidt U, Angermeyer MC, et al. Humanistic burden in schizophrenia: a literature review. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;54:85–93.

- Awad AG, Voruganti LN. Impact of atypical antipsychotics on quality of life in patients with schizophrenia. CNS Drugs. 2004;18:877–893.

- Bobes J, Arango C, Aranda P, et al. Cardiovascular and metabolic risk in outpatients with schizophrenia treated with antipsychotics: results of the CLAMORS Study. Schizophr Res. 2007;90:162–173.

- Brain C, Kymes S, DiBenedetti DB, et al. Experiences, attitudes, and perceptions of caregivers of individuals with treatment-resistant schizophrenia: a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:253.

- Shamsaei F, Cheraghi F, Bashirian S. Burden on family caregivers caring for patients with schizophrenia. Iran J Psychiatry. 2015;10:239–245.

- Nanko S, Moridaira J. Reproductive rates in schizophrenic outpatients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1993;87:400–404.

- Schomerus G, Schwahn C, Holzinger A, et al. Evolution of public attitudes about mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;125:440–452.

- Winklbaur B, Ebner N, Sachs G, et al. Substance abuse in patients with schizophrenia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2006;8:37–43.

- O’Day K, Rajagopalan K, Meyer K, et al. Long-term cost-effectiveness of atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of adults with schizophrenia in the US. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;5:459–470.

- Graham CN, Mauskopf JA, Lawson AH, et al. Updating and confirming an industry-sponsored pharmacoeconomic model: comparing two antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia. Value Health. 2012;15:55–64.

- Furiak NM, Ascher-Svanum H, Klein RW, et al. Cost-effectiveness model comparing olanzapine and other oral atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia in the United States. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2009;7:4.

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–276.

- Iancu I, Poreh A, Lehman B, et al. The Positive and Negative Symptoms Questionnaire: a self-report scale in schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry. 2005;46:61–66.

- William G. Clinical global impressions. ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology—Revised. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; Public Health Service, Alcohol; Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration: National Institute of Mental Health; Psychopharmacology Research Branch; Division of Extramural Research Programs; 1976; p. 218–222. OCLC 2344751. DHEW Publ No ADM 76–338 – via Internet Archive.

- Axelrod BN, Goldman RS, Alphs LD. Validation of the 16-item Negative Symptom Assessment. J Psychiatr Res. 1993;27:253–258.

- Beck AT, Baruch E, Balter JM, et al. A new instrument for measuring insight: the Beck Cognitive Insight Scale. Schizophr Res. 2004;68:319–329.

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, et al. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571.

- Day JC, Wood G, Dewey M, et al. A self-rating scale for measuring neuroleptic side-effects. Validation in a group of schizophrenic patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;166:650–653.

- Lindstrom E, Lewander T, Malm U, et al. Patient-rated versus clinician-rated side effects of drug treatment in schizophrenia. Clinical validation of a self-rating version of the UKU Side Effect Rating Scale (UKU-SERS-Pat). Nord J Psychiatry. 2001;55 :5–69.

- Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, et al. The global assessment scale. A procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1976;33:766–771.

- Birchwood M, Smith J, Cochrane R, et al. The Social Functioning Scale. The development and validation of a new scale of social adjustment for use in family intervention programmes with schizophrenic patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;157:853–859.

- Morosini PL, Magliano L, Brambilla L, et al. Development, reliability and acceptability of a new version of the DSM-IV Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) to assess routine social functioning. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101:323–329.

- Ustun TB, Chatterji S, Kostanjsek N, et al. Developing the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0. Bull WHO. 2010;88:815–823.

- Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4:353–365.

- Potkin S B-KD, Edgar C, Luo S. PRM30 evaluating readiness for work in patients with schizophrenia: “The Readiness for Work Questionnaire” (WoRQ). Value Health. 2012:15;A650.

- Kemp R, Kirov G, Everitt B, et al. Randomised controlled trial of compliance therapy. 18-month follow-up. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172:413–419.

- Thompson K, Kulkarni J, Sergejew AA. Reliability and validity of a new Medication Adherence Rating Scale (MARS) for the psychoses. Schizophr Res. 2000;42:241–247.

- Hogan TP, Awad AG, Eastwood R. A self-report scale predictive of drug compliance in schizophrenics: reliability and discriminative validity. Psychol Med. 1983;13:177–183.

- Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care. 1986;24:67–74.

- Vernon MK, Revicki DA, Awad AG, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Medication Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ) to assess satisfaction with antipsychotic medication among schizophrenia patients. Schizophr Res. 2010;118:271–278.

- Levene JE, Lancee WJ, Seeman MV. The perceived family burden scale: measurement and validation. Schizophr Res. 1996;22:151–157.

- Richieri R, Boyer L, Reine G, et al. The Schizophrenia Caregiver Quality of Life questionnaire (S-CGQoL): development and validation of an instrument to measure quality of life of caregivers of individuals with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2011;126:192–201.

- EuroQol G. EuroQol–a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208.

- Naber D. A self-rating to measure subjective effects of neuroleptic drugs, relationships to objective psychopathology, quality of life, compliance and other clinical variables. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1995;10:133–138.

- Heinrichs DW, Hanlon TE, Carpenter WT, Jr. The Quality of Life Scale: an instrument for rating the schizophrenic deficit syndrome. Schizophr Bull. 1984;10:388–398.

- Auquier P, Simeoni MC, Sapin C, et al. Development and validation of a patient-based health-related quality of life questionnaire in schizophrenia: the S-QoL. Schizophr Res. 2003;63:137–149.

- Wilkinson G, Hesdon B, Wild D, et al. Self-report quality of life measure for people with schizophrenia: the SQLS. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:42–46.

- Isjanovski V, Naumovska A, Bonevski D, et al. Validation of the Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale Revision 4 (SQLS-R4) among patients with schizophrenia. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2016;4:65–69.

- Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, et al. Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire: a new measure. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1993;29:321–326.

- Ware JE Jr., Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483.

- Montemagni C, Rocca P. Second-generation long-acting injectable antipsychotics in schizophrenia: patient functioning and quality of life [Review]. Neuropsych Dis Treat. 2016;12:917–929.

- Rocca P, Montemagni C, Zappia S, et al. Negative symptoms and everyday functioning in schizophrenia: a cross-sectional study in a real world-setting. Psychiat Res. 2014;218:284–289.

- Mazumder AH, Alam MT, Yoshii H, et al. Positive and negative symptoms in patients of schizophrenia: a cross sectional study. Acta Med Int. 2015;2:48–52.

- Karow A, Moritz S, Lambert M, et al. Remitted but still impaired? Symptomatic versus functional remission in patients with schizophrenia [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. Eur Psychiat. 2012;27:401–405.

- Dahlan R, Midin M, Shah SA, et al. Functional remission and employment among patients with schizophrenia in Malaysia. Compr Psychiat. 2014;55:S46–S51.

- Chang LR, Lin YH, Chang HC, et al. Psychopathology, rehospitalization and quality of life among patients with schizophrenia under home care case management in Taiwan [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. J Formos Med Assoc. 2013;112:208–215.

- Neto JH, Elkis H. Clinical aspects of super-refractory schizophrenia: a 6-month cohort observational study. Revista de Psiquiatria do Rio Grande do Sul. 2007;29:228–232.

- da Silva TFC, Mason V, Abelha L, et al. Quality of life assessment of patients with schizophrenic spectrum disorders from psychosocial care centers [Avaliacao da qualidade de vida dos pacientes com transtorno do espectro esquizofreico atendidos nos centros de atencao psicossocial na cidade do rio de janeiro.]. J Bras Psiquiatria. 2011;60:91–98.

- Wang XQ, Petrini MA, Morisky DE. Predictors of quality of life among Chinese people with schizophrenia. Nurs Health Sci. 2017;19:142–148.

- Razali SM, Yusoff MZ. Medication adherence in schizophrenia: a comparison between outpatients and relapse cases [Comparative Study; Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. East Asian Arch Psy. 2014;24:68–74.

- Rocca P, Montemagni C, Mingrone C, et al. A cluster-analytical approach toward real-world outcome in outpatients with stable schizophrenia. Eur Psychiat. 2016;32:48–54.

- Glick HA, Li P, Harvey PD. The relationship between Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) schizophrenia severity scores and risk for hospitalization: an analysis of the CATIE Schizophrenia Trial. Schizophr Res. 2015;166:110–114.

- Hong J, Windmeijer F, Novick D, et al. The cost of relapse in patients with schizophrenia in the European SOHO (Schizophrenia Outpatient Health Outcomes) study [Comparative Study; Multicenter Study; Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. Prog Neuro-Psychopha. 2009;33:835–841.

- Midin M, Razali R, ZamZam R, et al. Clinical and cognitive correlates of employment among patients with schizophrenia: a cross-sectional study in Malaysia. Int J Ment Health Sy. 2011;5 (no pagination)(14).

- Sicras-Mainar A, Maurino J, Ruiz-Beato E, et al. Impact of negative symptoms on healthcare resource utilization and associated costs in adult outpatients with schizophrenia: a population-based study [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:225.

- Mohr P, Rodriguez M, Bravermanova A, et al. Social and functional capacity of schizophrenia patients: a cross-sectional study. Int J Soc Psychiatr. 2014;60:352–358.

- Lambert M, Naber D, Eich FX, et al. Remission of severely impaired subjective wellbeing in 727 patients with schizophrenia treated with amisulpride [Clinical Trial; Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. Acta Psychiat Scand. 2007;115:106–113.

- Gorwood P. Factors associated with hospitalisation of patients with schizophrenia in four European countries [Multicenter Study; Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. Eur Psychiat. 2011;26:224–230.

- Alessandrini M, Lancon C, Fond G, et al. A structural equation modelling approach to explore the determinants of quality of life in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2016;171:27–34.

- Jager M, Weiser P, Becker T, et al. Identification of psychopathological course trajectories in schizophrenia [Multicenter Study; Ui - 52933903]. Psychiat Res. 2014;215:274–279.

- Witte MM, Case MG, Schuh KJ, et al. Effects of olanzapine long-acting injection on levels of functioning among acutely ill patients with schizophrenia [Multicenter Study; Randomized Controlled Trial; Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28:315–323.

- Sarlon E, Heider D, Millier A, et al. A prospective study of health care resource utilisation and selected costs of schizophrenia in France [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:269–276.

- Siani C, de Peretti C, Millier A, et al. Predictive models to estimate utility from clinical questionnaires in schizophrenia: findings from EuroSC [Multicenter Study]. Qual Life Res. 2016;25:925–934.

- Mohamed S, Rosenheck R, Swartz M, et al. Relationship of cognition and psychopathology to functional impairment in schizophrenia [Randomized Controlled Trial; Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. Am J Psychiat. 2008;165:978–987.

- Llorca PM, Blanc O, Samalin L, et al. Factors involved in the level of functioning of patients with schizophrenia according to latent variable modeling. Eur Psychiat. 2012;27:396–400.

- Rabinowitz J, Levine SZ, Garibaldi G, et al. Negative symptoms have greater impact on functioning than positive symptoms in schizophrenia: analysis of CATIE data. Schizophr Res. 2012;137:147–150.

- Karve SJP, J. M, Dirani RG, Candrilli SD. Health care utilization and costs among medicaid-enrolled patients with schizophrenia experiencing multiple psychiatric relapses. Health Out Res Med. 2012;3:e183–e194.

- Boyer L, Millier A, Perthame E, Aballea S, Auquier P, Toumi M. Quality of life is predictive of relapse in schizophrenia [Multicenter Study; Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:15.

- Bosia M, Marino E, Anselmetti S, et al. Influence of catechol-O-methyltransferase Val158Met polymorphism on neuropsychological and functional outcomes of classical rehabilitation and cognitive remediation in schizophrenia. Neurosci Lett. 2007;417:271–274.

- Miyaji S, Yamamoto K, Morita N, et al. The relationship between patient characteristics and psychiatric day care outcomes in schizophrenic patients. Psychiat Clin Neuros. 2008;62:293–300.

- Haro JM, Novick D, Perrin E, et al. Symptomatic remission and patient quality of life in an observational study of schizophrenia: Is there a relationship? Psychiat Res. 2014;220:163–169.

- Novick D, Haro JM, Suarez D, et al. Recovery in the outpatient setting: 36-month results from the Schizophrenia Outpatients Health Outcomes (SOHO) study. Schizophr Res. 2009;108:223–230.

- Potkin SG, Loze JY, Forray C, et al. Relationship between response to aripiprazole once-monthly and paliperidone palmitate on work readiness and functioning in schizophrenia: A post-hoc analysis of the QUALIFY study. PLoS One. 2017;12 (no pagination)(e0183475).

- Sarikaya Varlik DG, Uzun, UE, Varlik C, et al. Factors associated with re-hospitalizations in schizophrenia: a community mental health service research [Conference Abstract]. Eur Neuropsychopharm. 2015;2:S536–S537.

- Caqueo-Urizar A, Gutierrez-Maldonado J, Miranda-Castillo C. Quality of life in caregivers of patients with schizophrenia: a literature review. Health Qual Life Out. 2009;7:84.

- Chong HY, Teoh SL, Wu DB, et al. Global economic burden of schizophrenia: a systematic review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:357–373.

- Cloutier M, Aigbogun MS, Guerin A, et al. The economic burden of schizophrenia in the United States in 2013. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77:764–771.

- Hawthorne WB, Folsom DP, Sommerfeld DH, et al. Incarceration among adults who are in the public mental health system: rates, risk factors, and short-term outcomes. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63:26–32.