Abstract

Introduction: The patient cost burden of oral anticancer medicines has been associated with prescription abandonment, delayed treatment initiation, and poorer health outcomes in the US. Since 2011, several small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors have been approved for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients with rearrangement of the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene. The objective of this study was to measure the impact of copay assistance on patient cost sharing and treatment patterns in patients prescribed oral ALK inhibitors (ALKi’s).

Methods: Patterns of claims approval/rejection and payment/reversal, out-of-pocket (OOP) costs, and treatment persistence were reported for patients identified in the IQVIA Formulary Impact Analyzer database from January 2013 to August 2017 linked to a medical claims database. The primary study cohorts were patients with copay assistance, including manufacturer’s copay cards, other discount cards, or free-trial vouchers, on the index ALKi claim, and patients without copay assistance at any time during the follow-up period.

Results: In total, 3,143 patients were included in analyses related to claim patterns, and 1,685 patients were included in analyses related to treatment persistence. Copay assistance decreased the OOP cost for the first approved ALKi by $1,930, on average. Patients with copay assistance picked up ALKi prescriptions from the pharmacy sooner than patients without copay assistance (2.6 days vs 25.7 days). In adjusted analyses, patients with copay assistance had 88.2% lower risk of abandoning their first approved prescription and 24.3% lower risk of discontinuing treatment with the first observed ALKi (all p < 0.001).

Conclusion: Copay assistance reduced the patient cost burden for ALKi’s and was associated with patients picking up their ALKi prescriptions, beginning ALKi treatment sooner, and remaining on treatment.

Introduction

Oral anticancer medications (OAMs) have had a notable impact on patient out-of-pocket (OOP) spending, which accounted for $6.3 billion in payments for cancer care from 2010 to 2012 in the USCitation1. Despite insurance coverage, the cost of cancer care can be unmanageable for many, and patients may resort to cost-saving mechanisms such as not filling prescriptions, taking less than the prescribed amount, discontinuing treatment, or delaying treatmentCitation2–4.

To help patients better manage the cost of cancer care, patient assistance programs (PAPs) sponsored by drug manufacturers or private foundations can help eligible patients reduce their OOP costs by providing free medications, discounts using copay cards, or direct payments to pharmaciesCitation5. According to a recent report on oncology trends, 37% of the prescriptions for OAMs filled with commercial insurance used a manufacturer coupon in 2017, reducing the cost of each prescription by $526, on averageCitation6. Furthermore, lowering OOP costs may also improve patient outcomes by reducing time to receipt of the drug and by increasing treatment adherence. In two studies using Medicare data, patients that received cost-sharing subsidies initiated OAMs faster than patients without these subsidies, suggesting that high OOP costs may delay treatmentCitation7,Citation8. Findings from studies of rheumatoid arthritisCitation9, chronic myeloid leukemiaCitation8,Citation10, and type 2 diabetesCitation11 patients indicate that treatment adherence decreases with higher OOP costs. Through these pathways of reducing the time to treatment initiation and improving treatment adherence, reduced OOP costs may lessen unnecessary healthcare utilization. For example, an evaluation of a pilot program that facilitated enrollment in prescription assistance found that patients had a 51% decline in the rate of emergency department and hospital utilization after receiving assistance across a range of drug types (including antihyperglycemic, psychotropic, and cardiovascular medications)Citation12.

Among the recently approved OAMs are targeted therapies for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with rearrangement of the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene, which is present in 2–7% of all NSCLC patientsCitation13, and can be targeted using small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors to block oncogenic activityCitation14. In clinical trials, patients treated with the first-generation ALK inhibitor (ALKi) crizotinib demonstrated longer median progression-free survival than patients treated with standard cytotoxic chemotherapyCitation15,Citation16. With the approval of the second-generation ALKi’s ceritinib, alectinib, and brigatinib, treatment options for ALK-positive NSCLC have increased. Despite the clinical benefits of ALKi’s, as with other OAMs, the cost of treatment may deter use of these therapiesCitation17–19. To help lower OOP costs, copay assistance is available to eligible patients, including copay cards that can reduce copays to between $0 and $25 per monthCitation20–23.

Using real-world data, this study aimed to characterize copay assistance for ALKi’s, measure patient OOP payments, and measure how copay assistance impacts ALKi utilization, including describing claims approval, claims reversal, and treatment persistence among patients with and without copay assistance. This study adds to the current body of research on the impact of copay assistance programs, and measures the benefit of these programs in helping patients receive treatment.

Methods

Data sources

This was a retrospective cohort study of patients prescribed ALKi’s approved for the treatment of ALK-positive NSCLC (crizotinib, ceritinib, alectinib, and brigatinib). Patients were identified from the IQVIA Formulary Impact Analyzer (FIA) database, a transactional claims database sourced from retail and mail-order pharmacies that captures the full lifecycle of claims. A complete prescription claim cycle in FIA has a final decision of rejected by the health plan or approved by the health plan, and then either accepted (paid and picked up from the pharmacy) or reversed (abandoned/left at the pharmacy) by the patient. A claim in FIA also has information on whether there is a manufacturer’s copay card, other discount card, or free-trial voucher transaction associated with payments, and patient’s OOP cost before and after any copay card transactions. However, the use of e-coupon vouchers and denial conversion programs were not captured in our dataset. Details on insurance plan benefit design, reasons for treatment discontinuation, and use and costs of other medications were also not available. The FIA database covers 63% of prescriptions dispensed from retail pharmacies and 52% of prescriptions dispensed from specialty pharmacies in the US. Data from the FIA database was linked to the IQVIA Medical Claims (Dx) database, which includes International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) and ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes, outpatient medical and service procedures, and patient demographic information.

Patient selection

The study period was from January 1, 2013 to August 31, 2017 for the FIA database and January 1, 2012 to August 31, 2017 for the Dx database. All patients had a 12-month baseline period and variable follow-up period with a minimum of 1 month. Two analytic datasets were created for this study: (1) patients with evidence of ≥1 complete claim cycle for an ALKi were included in analyses related to patterns of claims approval/rejection and payment/reversal, and were indexed on the date of the first claim cycle (irrespective of the final claim status, i.e. whether the claim was rejected, paid, or reversed); and (2) patients with evidence of ≥1 completed paid claim cycle for an ALKi were included in the treatment persistence analysis, and were indexed on the date of the first paid claim cycle. Additionally, patients included in the persistence analysis were required to have ≥6 months of active claim activity in the FIA database (i.e. minimum 6 months follow-up period). All patients were 18–85 years of age on the index date. Patients with missing age, sex, payer, or other data quality issues were excluded.

The study cohorts were patients with copay assistance at the index claim cycle and patients without copay assistance at any time in the study period. Copay assistance was identified using a variable that captured free trial vouchers and discount cards from the manufacturer or other sources. Patients who did not have copay assistance at the index claim cycle, but had evidence of copay assistance at a later claim cycle, were excluded from each dataset, since they may represent a distinct group that required more time to receive copay assistance.

Outcome measures

Among patients with ≥ 1 ALKi claim, the number and proportion of patients with either approved or rejected claims on the index claim cycle and for subsequent claim cycles during the follow-up period were identified in the FIA data. Patients with an approved claim were further described as having either a paid or reversed claim. OOP costs for the first approved claim were described, including initial OOP cost, the amount of the copay subsidy applied to the transaction (for copay assistance cohort only), and the final OOP cost to the patient. Reasons for claim rejection were reported using the last observed ALKi claim cycle, given that the first ALKi claim may be rejected due to administrative errors that are corrected on a subsequent claim. Additionally, time to the first approved claim and time to the first paid claim was described for these patients with ≥ 1 paid claim. Among patients with ≥ 1 paid ALKi claim, OOP costs and persistence (days on therapy) to the first paid ALKi over 1 year were reported.

Statistical methods

All measures were reported as descriptive statistics by the copay assistance cohort using frequency and percentage distributions for categorical variables and descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation [SD]) for continuous and count variables. Statistical differences between cohorts were assessed using a two-sided t-test comparing means of continuous variables and Pearson’s Chi-square test for categorical variables.

The association between copay assistance and reversal of the first approved claim was estimated using a Poisson regression model in the sample of patients with ≥ 1 ALKi claim. Among patients with ≥ 1 paid ALKi claim, the probability of treatment discontinuation was estimated using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and compared using a log-rank test. Patients who did not discontinue treatment were censored when switching to a different ALKi, at the end of follow-up, or 1 year, whichever occurred first.

Persistence was defined as the number of consecutive days from the index date until discontinuation of the first paid ALKi, switch to a different ALKi, end of follow-up, or 1 year, whichever occurred first. Discontinuation was defined as a gap in medication supply (days between run-out date of the ALKi and the next fill date) of > 60 days, similar to previous studies on persistence OAMs in NSCLCCitation24 and colorectal cancerCitation25. A sensitivity analysis was also conducted where discontinuation was defined using a shorter gap of > 30 days. The association between copay assistance on persistence to the first paid ALKi at 1 year was estimated using a Cox proportional hazards model.

Both multivariable models were adjusted for the following baseline characteristics: age (continuous), sex, payer type (Commercial, Medicare Part D, other), provider specialty (oncologist, internal medicine, other), Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI, continuous), prior use of chemotherapy, and the initial OOP cost for the first approved ALKi (for reversal analysis) or index paid ALKi (for persistence analysis) before copay assistance (continuous, in $100 units). Patients with missing data on initial OOP cost were excluded from regression analyses (n = 71 excluded for analysis related to prescription reversal and n = 51 excluded for analysis related to persistence).

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

Results

Sample

A total of 3,385 individuals with ≥ 1 ALKi claim were identified; 242 (7.1%) patients with evidence of copay assistance only on claims after the first ALKi claim (non-first claim copay assistance) were excluded, and the final sample consisted of 3,143 patients. Of this, 570 (18.1%) had copay assistance on the index claim, and 2,573 (81.9%) had no copay assistance at any time during the follow-up period. Patients with copay assistance were older, on average (mean = 65.0 years vs 60.0 years, p < 0.001), more likely to be enrolled in Medicare Part D (58.8% vs 30.2%, p < 0.001), and more likely to have had an oncologist prescribe the index ALKi (43.3% vs 35.4%, p < 0.001). Both cohorts demonstrated similar distributions for sex, CCI, brain metastasis diagnosis, and prior use of chemotherapy. The distribution of ALKi’s on the index claim was also similar in both copay assistance and no copay assistance cohorts, with more than 85% of patients indexed on the 1st generation ALKi crizotinib. Baseline characteristics of patients with ≥ 1 ALKi claim are described in .

Table 1. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics for patients with ≥ 1 ALKi claim (n = 3,143) and patients with ≥ 1 paid ALKi claim (n = 1,687).

In total, 1,825 individuals with ≥ 1 paid ALKi claim were identified; 138 (7.6%) with non-first claim copay assistance were excluded. Of the final sample of 1,687 patients, 652 (38.7%) had copay assistance on the index claim, and 1,035 (61.4%) had no copay assistance at any time during the follow-up period. Baseline characteristics of patients indexed on the first paid ALKi claim (n = 1,687) are also described in .

Patterns of approved and rejected claims

A higher proportion of patients with copay assistance had an approved ALKi claim during the follow-up period (98.4% of patients with copay assistance vs 55.3% of patients with no copay assistance, p < 0.001). More patients with copay assistance also had their first ALKi claim approved compared to patients with no copay assistance (99.1% vs 91.8%, p < 0.001). Among patients whose first ALKi claim was rejected, most patients in both cohorts (copay assistance and no copay assistance) were eventually able to get the same ALKi they attempted to fill as their first approved ALKi (100.0% vs 67.5%, p = 0.32). The time from index claim to first insurance approval of an ALKi prescription was shorter for patients with copay assistance compared to patients without copay assistance (mean [SD] days = 0.5 [7.6] vs 15.2 [86.6], p < 0.001).

Table 2. ALKi claim decisions, among patients with ≥ 1 ALKi claim (n = 3,143).

Compared to patients without copay assistance, fewer patients with copay assistance had rejected ALKi claims only during the follow-up period (1.6% vs 44.7%, p < 0.001). For patients without copay assistance, the most common reasons for rejection were prior authorization requirement (23.5%) and product not covered (13.1%).

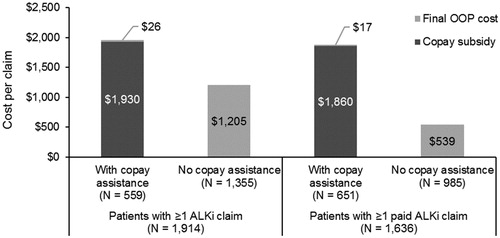

OOP costs

For patients with at least one approved ALKi claim, the initial OOP cost tended to be higher among patients with copay assistance compared to those without copay assistance (mean [SD] = $1,956 [$1,605] vs $1,210 [$3,543], p < 0.001). After adjusting with copay assistance (mean copay subsidy [SD] = $1,930 [$1,606]), patients with copay assistance had lower mean OOP costs for their first approved ALKi than patients without copay assistance (mean [SD] = $26 [$229] vs $1,205 [$3,543], p < 0.001). OOP costs for the first paid ALKi claim are shown in .

Figure 1. Out-of-pocket cost and copay subsidy amount for first approved ALKi, among patients with approved ALKi (n = 1,914) and patients with paid ALKi claims (n = 1,636). Data on OOP costs were available for 559 (99.6%) patients with copay assistance and 1,355 (95.2%) patients without copay assistance in the sample of patients with ≥1 ALKi claim and for 651 (99.8%) patients with copay assistance and 985 (95.2%) patients without copay assistance with ≥1 paid ALKi claim.

Patterns of picked up and reversed claims

Patients with copay assistance were less likely to abandon their initial ALKi prescription than patients without copay assistance (4.3% vs 33.3%, p < 0.001). In the adjusted analysis, patients with copay assistance had an 88.2% lower risk of abandoning their first approved claim (risk ratio, RR [95% confidence interval, CI] = 0.12 [0.08–0.18]). Patients with higher initial OOP costs (RR [95% CI] = 1.01 [1.00–1.01]) were also significantly more likely to reverse their first approved claim. Furthermore, for patients who picked up their ALKi prescription (paid claim), the time from the index claim to the first picked up prescription was shorter for patients with copay assistance compared to patients without copay assistance (unadjusted mean [SD] days = 2.6 [28.7] vs 25.7 [115.3], p < 0.001).

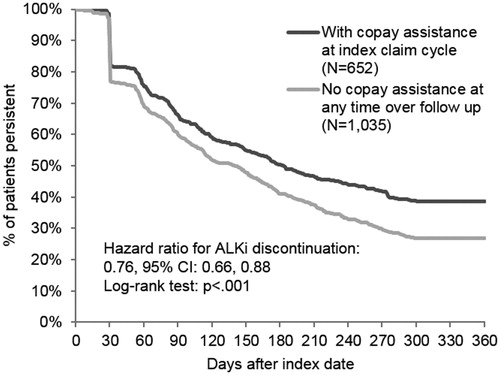

Persistence to ALKi treatment

The Kaplan-Meier curve in demonstrates that patients with copay assistance were more likely to remain on their first ALKi over the 1-year follow-up compared to patients without copay assistance (median days on treatment [95% CI] = 183 [158–215] vs 140 [115–154]; log-rank test p-value < 0.001). In the adjusted analysis, patients with copay assistance had a 24.3% lower risk of ALKi discontinuation than patients without copay assistance (hazard ratio, HR [95% CI] = 0.76 [0.66–0.88]). Additionally, patients with commercial payers compared to patients with Medicare Part D (HR [95% CI] = 1.30 [1.11–1.52]) and patients with higher initial OOP costs (HR [95% CI] = 1.00 [1.00–1.01]) were significantly more likely to discontinue treatment. All other covariates were not significantly associated with the risk of ALKi discontinuation. The results of the sensitivity analysis using a > 30-day gap definition of ALKi discontinuation were consistent with the findings from the main analysis. Under this more stringent definition, time to ALKi discontinuation remained longer for patients with copay assistance compared to those without copay assistance (median days on treatment [95% CI] = 111 [94–133] vs 90 [83–99]; log-rank test p-value < 0.001) and patients with copay assistance had a lower risk of ALKi discontinuation (HR [95% CI] = 0.82 [0.73–0.93]).

Discussion and conclusion

The findings of this study suggest that copay assistance programs in the US and the large copay subsidies they provide may encourage ALKi treatment. Patients with copay assistance were more likely to pick up their ALKi prescriptions than patients without copay assistance, as shown by an 88.2% lower risk of prescription reversal. Patients with copay assistance also picked up their prescriptions sooner than those without copay assistance (2.6 days vs 25.7 days). Finally, patients with copay assistance were more likely to remain on treatment, with a 24% lower risk of discontinuing treatment than those without copay assistance.

Prior studies of institutional assistance programs have suggested they have had a growing role in helping patients, including those with private or public insurance, overcome financial barriers in access to OAMsCitation26,Citation27. Our study is one of the first to examine the association between PAPs and OAM treatment persistence. Using a database with broad coverage of paid claims in retail and specialty/mail order pharmacies that also captures the full lifecycle of claims enabled us to identify the use of copay assistance and describe patterns of ALKi approvals, payments, and reversals. Our findings regarding OOP costs and prescription reversals are consistent with the previously published literature, although the heterogeneity of patient populations and the types of financial assistance examined impairs direct comparisons between studies. In our sample, copay assistance yielded large OOP cost reductions and reduced the OOP costs of approved ALKi claims to 1% of the initial cost (from $1,956 to $26, on average) and other studies of manufacturer- or foundation-sponsored financial assistance and low-income subsidies for Medicare patients have also demonstrated large savings, ranging from $411 to more than $2,000Citation7,Citation28,Citation29. Our findings that patients with copay assistance had lower rates of claim reversal were also in line with previous studies suggesting that higher OOP costs may deter patients from filling their prescriptions or continuing treatmentCitation3,Citation7,Citation8,Citation30,Citation31. Doshi et al.Citation31, for example, reported that the rate of claim reversal for OAMs was 67% in patients with OOP costs exceeding $2,000, and 13% in patients with OOP costs of $10 or less. In our adjusted analyses, higher initial OOP cost, regardless of copay assistance, also predicted claim reversal.

We found patients with copay assistance stay on their first ALKi treatment longer than patients without copay assistance. Patients with higher initial OOP costs had significantly higher risks of discontinuing their first ALKi, as well, although the effect estimate was small. These findings are consistent with previous research on predictors of adherence to OAMsCitation32,33. Further investigation is needed to understand the clinical implications of these results, given improved overall survival and progression-free survival demonstrated with the use of ALKi’sCitation34. Furthermore, the overall estimate of time to discontinuation should be interpreted in the context of the time period of the study (2013–2017), as we observed that crizotinib was the predominant index ALKi and the standard of care has recently shifted toward the 2nd generation ALKi alectinib in 2018Citation35. In the phase III ALEX study, alectinib more than doubled median progression-free survival compared to crizotinib and, hence, the overall treatment duration in this study may underestimate the current treatment durations in practiceCitation36,Citation37, and future studies should assess treatment persistence by an individual ALK inhibitor. Although it was unclear how copay assistance itself would determine clinical outcomes, mediating factors, such as reducing the adverse effects of financial stressCitation38, influencing the patient’s decision to pick up their ALKi’s from the pharmacy, or shortening the time to treatment initiation, could play a role in improving ALKi treatment rates and patient outcomes.

Our findings should be interpreted in the context of study limitations. As with other retrospective claims database studies, there is potential for data entry error, upcoding, under-coding of metastasesCitation39 and chemotherapy use, and misclassification of outcomes. For example, we are unable to confirm if patients had picked up their prescriptions outside the FIA pharmacy network, so our reported persistence may be under-estimated. Additionally, since the use of other PAPs (e.g. e-coupon vouchers and denial conversion programs) are not identifiable in our FIA dataset, the estimates of differences in OOP costs and outcomes (claims reversal and treatment persistence) by copay assistance may be even larger. Unobserved factors such as patient financial circumstances, the physician’s decision-making process to prescribe treatments based on costCitation40, switching treatments due to physician’s recommendation, or other characteristics which determine copay assistance eligibility and patient’s copay assistance/treatment seeking behavior may also confound the study findings. Given that the distribution of payer types differed significantly between the copay assistance cohorts, identification of differences in pharmacy benefit design could provide further context for our findings, including patterns in claims approval and rejection that would not necessarily be explained by the use of copay assistance and the higher initial OOP costs observed among patients with copay assistance. Other factors not investigated in the current study, including the first ALKi prescription fill months and use and OOP costs of other prescription drugs, may also help explain the differences in the initial OOP costs between the cohorts. Patients who filled their first ALKi prescription later in the calendar year or had filled and paid for other medications earlier in the year may have met their deductible requirement, contributing to the lower initial OOP costs of their ALKi prescription. Moreover, given only OOP costs for the first approved or first paid ALKi were identified in this study, it is unknown whether changes in OOP costs over time may have influenced treatment persistence. Further examination of cost data would be warranted, especially for Medicare Part D enrollees, as their OOP costs vary depending on their drug coverage phaseCitation41. Finally, the exclusion of patients that received copay assistance only for a later claim (non-first claim support) in our study lowers the generalizability of these findings to other forms of financial assistance that require longer processing times. In one institutional study, a substantial proportion of patients with cancer received copay assistance via a patient advocacy or private foundation which can require a time-consuming application process for determining eligibilityCitation27. Despite potential differences between this patient group and our analytic cohorts, fewer than 8% of individuals in our sample fell under this non-first claim support category.

Although this study demonstrated that copay assistance can greatly reduce patient OOP costs for ALKi’s, continued research is needed on methods to alleviate patient financial burden as the US healthcare system evolves over time. For example, in 2018, shortly after the end of our study period, some pharmacy benefit managers began adopting copay accumulator programs, a benefit design that prevents copay assistance payments from counting towards a patient’s deductibleCitation42, and this may change the impact of copay assistance payments on treatment rates. The real-world impact of copay accumulator programs remains unknown, and studies of copay assistance using newer data, once available, would need to consider these programs as a source of confounding. Potential legislative approaches to improve the affordability of new OAMs in the long-term, such as value-based pricing and encouraging a more competitive drug marketCitation43, would also require consideration in future studies.

To conclude, copay assistance can dramatically decrease short-term patient financial burden and, through reducing the risk of prescription reversals and treatment discontinuation, may increase the use of ALKi’s and improve patient outcomes. Additional real-world studies are needed to evaluate the long-term benefits of PAPs on ALKi use and clinical outcomes.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This paper, including medical writing, was funded by Genentech Inc.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

AS, JT, and CB were contracted by Genentech Inc. to conduct this study. WW is an employee of Genentech Inc. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Previous presentations

This study was previously presented at the AMCP Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy Annual Meeting, Boston, MA, April 23–26, 2018.

Compliance with ethical standards

This study was based on secondary, de-identified data, which comply with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Institutional review board approval was not required for this study.

Acknowledgements

Programming assistance was provided by Jing He and Estella Yi Wang of IQVIA. Medical writing assistance was provided by Michael Behling of IQVIA.

References

- Lee JA, Roehrig CS, Butto ED. Cancer care cost trends in the United States: 1998 to 2012. Cancer. 2016;122:1078–1084.

- Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: a pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient's experience. Oncologist. 2013;18:381–390.

- Kaisaeng N, Harpe SE, Carroll NV. Out-of-pocket costs and oral cancer medication discontinuation in the elderly. JMCP. 2014;20:669–675.

- Streeter SB, Schwartzberg L, Husain N, et al. Patient and plan characteristics affecting abandonment of oral oncolytic prescriptions. JOP. 2011;7:46s–51s.

- Yezefski T, Schwemm A, Lentz M, et al. Patient assistance programs: a valuable, yet imperfect, way to ease the financial toxicity of cancer care. Semin Hematol. 2017;55:185–188.

- IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science. Global Oncology Trends 2018 Parsippany, NJ2018 [cited 2019 January 4]. Available from: https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/institute-reports/global-oncology-trends-2018.pdf

- Li P, Wong Y-N, Jahnke J, et al. Association of high cost sharing and targeted therapy initiation among elderly medicare patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2018;7:75–86.

- Winn AN, Keating NL, Dusetzina SB. Factors associated with tyrosine kinase inhibitor initiation and adherence among medicare beneficiaries with chronic myeloid leukemia. JCO. 2016;34:4323–4328.

- Curkendall S, Patel V, Gleeson M, et al. Compliance with biologic therapies for rheumatoid arthritis: do patient out-of-pocket payments matter? Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1519–1526.

- StCharles M, Bollu VK, Hornyak E, et al. Predictors of treatment non-adherence in patients treated with imatinib mesylate for chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2009;114:2209.

- Bibeau WS, Fu H, Taylor AD, et al. Impact of out-of-pocket pharmacy costs on branded medication adherence among patients with type 2 diabetes. JMCP. 2016;22:1338–1347.

- Burley MH, Daratha KB, Tuttle K, et al. Connecting patients to prescription assistance programs: effects on emergency department and hospital utilization. JMCP. 2016;22:381–387.

- Kwak EL, Bang YJ, Camidge DR, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1693–1703.

- Koivunen JP, Mermel C, Zejnullahu K, et al. EML4-ALK fusion gene and efficacy of an ALK kinase inhibitor in lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4275–4283.

- Shaw AT, Kim D-W, Nakagawa K, et al. Crizotinib versus chemotherapy in advanced ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2385–2394.

- Solomon BJ, Mok T, Kim DW, et al. First-line crizotinib versus chemotherapy in ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2167–2177.

- Chustecka Z. Price of new cancer drugs as high as market can bear: medscape; 2014 [cited 2017 Sep 26]. Available from: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/830145

- Elliot W, Chan J. Brigatinib tablets (alunbrig): AHC media; 2017 [cited 2017 October 17]. Available from: https://www.ahcmedia.com/articles/140851-brigatinib-tablets-alunbrig

- Levitan D. First-Line alectinib tops crizotinib in ALK-Positive NSCLC: cancer network; 2016 [cited 2017 Sep 26]. Available from: http://www.cancernetwork.com/lung-cancer/first-line-alectinib-tops-crizotinib-alk-positive-nsclc

- Novartis. About the Co-Pay Card; 2018 [cited 2018 Jul 25]. Available from: https://www.us.zykadia.com/patient-support/financial-resources/

- Pfizer Oncology Together. Financial assistance XALKORI (critonib); 2018 [cited 2018 July 25]. Available from: https://www.pfizeroncologytogether.com/patient/xalkori/patient-financial-assistance

- Takeda Oncology. Alunbrig co-pay card; 2017 [cited 2018 Jul 25]. Available from: https://sservices.trialcard.com/Coupon/Alunbrig

- Genentech. Referrals to the genentech biooncology co-pay card; 2018 [cited 2018 Jul 25]. Available from: https://www.genentech-access.com/hcp/brands/alecensa/find-patient-assistance/co-pay-cards.html

- Hess LM, Louder A, Winfree K, et al. Factors associated with adherence to and treatment duration of erlotinib among patients with non-small cell lung cancer. JMCP. 2017;23:643–652.

- Patel AK, Duh MS, Barghout V, et al. Real-world treatment patterns among patients with colorectal cancer treated with trifluridine/tipiracil and regorafenib. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2018;17:e531–e539.

- Felder TM, Lal LS, Bennett CL, et al. Cancer patients’ use of pharmaceutical patient assistance programs in the outpatient pharmacy at a large tertiary cancer center. Community Oncol. 2011;8:279–286.

- Mitchell A, Muluneh B, Patel R, et al. Pharmaceutical assistance programs for cancer patients in the era of orally administered chemotherapeutics. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2017;24:1078155217719585.

- Wong Y-N, Meeker C, Doyle J, et al. Human capital costs of obtaining oral anticancer medications. JCO. 2016;34:6506.

- Zullig LL, Wolf S, Vlastelica L, et al. The role of patient financial assistance programs in reducing costs for cancer patients. JMCP. 2017;23:407–411.

- Doshi JA, Li P, Huo H, et al. High cost sharing and specialty drug initiation under medicare Part D: a case study in patients with newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22:s78–s86.

- Doshi JA, Li P, Huo H, et al. Association of patient out-of-pocket costs with prescription abandonment and delay in fills of novel oral anticancer agents. JCO. 2018;36:476–482.

- Sedjo RL, Devine S. Predictors of non-adherence to aromatase inhibitors among commercially insured women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;125:191–200.

- Neugut AI, Subar M, Wilde ET, et al. Association between prescription co-payment amount and compliance with adjuvant hormonal therapy in women with early-stage breast cancer. JCO. 2011;29:2534–2542.

- Li G, Dai WR, Shao FC. Effect of ALK-inhibitors in the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2017;21:3496–3503.

- NCCN Guidelines Version 6; 2018. Non-small cell lung cancer: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2018 [cited 2018 Aug 24]. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nscl.pdf

- Camidge DR, Peters S, Mok T, et al. Updated efficacy and safety data from the global phase III ALEX study of alectinib (ALC) vs crizotinib (CZ) in untreated advanced ALK + NSCLC. JCO. 2018;26:9043–9043.

- Peters S, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, et al. Alectinib versus crizotinib in untreated ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med.. 2017;377:829–838.

- Carrera PM, Kantarjian HM, Blinder VS. The financial burden and distress of patients with cancer: understanding and stepping-up action on the financial toxicity of cancer treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:153–165.

- Nordstrom BL, Whyte JL, Stolar M, et al. Identification of metastatic cancer in claims data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21:21–28.

- Neumann PJ, Palmer JA, Nadler E, et al. Cancer therapy costs influence treatment: a national survey of oncologists. Health Aff. 2010;29:196–202.

- Shen C, Zhao B, Liu L, et al. Financial burden for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia enrolled in medicare part D taking targeted oral anticancer medications. JOP. 2017;13:e152–e162.

- Erman M, Humer C. U.S. drug prices hit by insurer tactic against copay assistance: analysis. Reuters; 2 August 2018. Available from: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-healthcare-drugpricing/u-s-drug-prices-hit-by-insurer-tactic-against-copay-assistance-analysis-idUSKCN1J2005

- Policy Strategies For Aligning Price And Value For Brand-Name Pharmaceuticals. Health Affairs Policy Options Paper, March 15, 2018. DOI: 10.1377/hpb20180216.92303