Abstract

Background: Residential step-up/step-down services provide transitional care and reintegration into the community for individuals experiencing episodes of subacute mental illness. This study aims to examine psychiatric inpatient admissions, length of stay, and per capita cost of care following the establishment of a step-up/step-down Prevention And Recovery Care (PARC) facility in regional Australia.

Methods: This was a pragmatic before and after study set within a participatory action research methodology. The target sample comprised patients at a PARC facility over 15 months. Six-month individual level data prior to study entry, during, and over 6-months from study exit were examined using patient activity records. Costs were expressed in 2015–2016AU$.

Results: An audit included 192 people experiencing 243 episodes of care represented by males (58%), mean age = 39.3 years (SD = 12.7), primarily diagnosed with schizophrenia (48%) or mood disorders (30%). The cost of 1 day in a psychiatric inpatient unit was found to be comparable to an average of 5 treatment days in PARC; the mean cost difference per-bed day (AU$1,167) was associated with fewer and shorter inpatient stays. Reduced use of inpatient facility translated into an opportunity cost of improved patient flow equivalent to AU$12,555 per resident (bootstrapped 95% CI = $5,680–$19,280). More noticeable outcomes were observed among those who stayed in PARC for longer during index admission (rs = 0.16, p = 0.024), who have had more and lengthy inpatient stays (rs = 0.52, p < 0.001 and rs = 0.69, p < 0.001), and those who stepped-down from the hospital (p < 0.001). This information could be proactively used within step-up/step-down services to target care to patients most likely to benefit. Despite early evidence of positive association, the results warrant further investigation using an experimental study design with alongside economic evaluation.

Conclusion: Efforts should be directed toward the adoption of cost-effective alternatives to psychiatric inpatient facilities that provide comparable or improved patient outcomes.

Introduction

In recent decades, a number of community-based alternatives to inpatient care have been implemented to meet the rising demand for mental health servicesCitation1,Citation2. Prevention And Recovery Care (PARC) is a subacute step-up/step-down community-based model of service delivery introduced to metropolitan Melbourne and regional Victoria in Australia in 2003Citation3. In the service continuum, PARC sits between psychiatric inpatient units and provision of intensive community treatment. PARC services support individuals with subacute symptoms who are in the community, experiencing a change in their mental health, and those who are in the early stages of recovery from an acute illness and need a short period of support to strengthen and consolidate their community transition and treatment plansCitation3–5.

Recovery-oriented practice is a core focus of current Australian mental health policyCitation6. Recovery support refers not only to processes and conditions of the person to reclaim meaning and purpose of life, healing, wellbeing, and control of symptoms, but also to external conditions and social processes such as skills training, peer support, and vocational servicesCitation7–9. The PARC model falls within a stepped care framework, which is a contemporary theory guiding mental health system design in Australia and internationallyCitation10,Citation11.

Although step-up/step-down care services are proliferating, only a few have been evaluatedCitation1,Citation12,Citation13, with most of the evaluations being reported in the grey literatureCitation14,Citation15. A systematic literature review that examined clinical and cost-effectiveness of acute and subacute residential mental health services found that most studies of acute residential units demonstrated clinical improvements equal to those of inpatient units and similar readmission rates, as well as cost benefitsCitation1. According to the same review, the evidence for subacute residential units was lacking, as the number and quality of studies with subacute units was limited and not sufficient to evaluate their effectiveness. The present study aims to examine the cost of a subacute step-up/step-down residential mental health service and inpatient cost-offsets associated with the service and contribute to the sparse evidence base.

This article reports on the findings of a project designed in collaboration with a mental health provider, Mind Australia; a local hospital, Cairns and Hinterland Hospital and Health Service (CHHHS); and a research group. The CHHHS is a major health provider in the far north Queensland region of Australia. As a result of increasing demand and limited resources, mental healthcare in the region was under increasing pressure to enhance its efficiencyCitation16,Citation17. The need for care transitions as an intervention for reducing readmission rates had become critical in the region and led to the establishment of the first PARC facility in Cairns in 2015Citation18.

Part of the remit of the project was to develop an evaluation framework for the service intervention and to measure whether the model met its objectives as viewed by staff members, residents, their families, and carers. The results were reported elsewhereCitation19. This paper reflects the value of resources used by the service and captures wider systems effects by assessing whether establishment of the step-up/step-down service resulted in reduced psychiatric inpatient admissions, shortened average length of stay, and reduced per capita cost of care. Hospital admission rate has been used as an indicator of the effectiveness of the service and its ability to provide continuous care across servicesCitation20,Citation21. We tested the following five research hypotheses:

PARC was associated with a reduction in number of psychiatric inpatient admissions.

PARC was associated with a reduction in the length of psychiatric inpatient admissions.

PARC residents were more likely to be readmitted to the facility from the community (stepping up) vs inpatient psychiatric unit (stepping down).

There was a difference in the length of subsequent inpatient admissions following index PARC stay by the type of diagnoses.

PARC residents incurred cost reduction in psychiatric admissions.

Methods

Study design

This was a pragmatic uncontrolled before and after study design set within a participatory action research methodologyCitation22–24. The principles of participatory action research guided the evaluation team, who acted as facilitators, engaging with stakeholders to determine the scope of the evaluation, define research questions, identify data sources, and inform the data collection processCitation25.

The target sample comprised consecutively admitted patients to the PARC facility in Cairns (regional Queensland, Australia) over 15 months, between May 2015 and July 2016 (inclusive). Exclusion criteria were admissions for electroconvulsive therapy or transfers to a community care unit. These cases were excluded on the grounds that PARC acted as an intermediary, rather than a recovery facility.

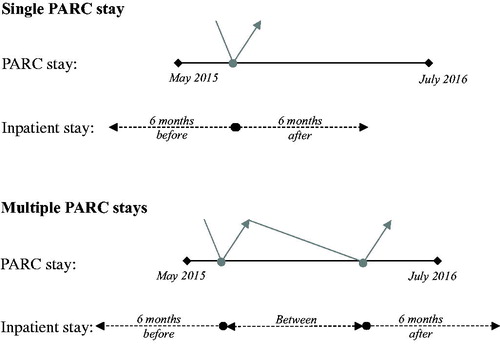

Individual level data were tested for differences in the number, length of stay, and cost of psychiatric admissions in the 6 months prior to study entry (PARC index admission), during the study, and over 6 months from study exit date. Separate analyses were performed for those who experienced one PARC admission vs those who experienced two or more readmissions during the study period. Because the number of PARC stays during the study period appeared to have clinically relevant implications, data for study participants as single and multiple stay residents were analyzed and reported separately. This decision was made a priori, on the assumption that multiple readmissions to PARC may indicate severe manifestation of a disorder and act as a possible confounding factor ().

Setting

The PARC service is provided to the CHHHS district with catchment population of ∼235,000 residents. PARC operates a 24-h multidisciplinary staffed home-like facility with 11 self-contained individual apartments and one shared studio apartment on a residential street in central Cairns. All apartments are fully equipped. The complex includes a communal living area, barbeque, and recreational areas. There is no charge for accommodation or meals. Residents are expected to contribute to the running of the facility, including assisting with cooking of shared meals, and cleaning. The service provides a mixture of structured activity and individual one-on-one support time. With residents’ consent, families and carers are actively involved in care planning, psycho-education, and referral to community support services.

PARC admissions are voluntary. People with increased illness acuity can enter as a step-up from community, while inpatients still requiring residential level of care can step-down from inpatient units with the aim of averting psychiatric hospital admissions and reducing inpatient length of stay. The Supplementary Appendix contains a schematic of the PARC service.

Measures

De-identified data on readmissions and lengths of stay were provided by the PARC service manager and retrospectively extracted from CHHHS computerized patient activity records. The following outcome variables were investigated by the type of stay (single or multiple): number, length and cost of stay at a hospital psychiatric unit. Covariates included age, sex, entry destination (step-down/step-up), length of stay at the PARC facility, and primary diagnosis coded according to the 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10)Citation26. The Business Finance and Performance team provided the average unit cost of a bed-day at the CHHHS Psychiatric Adult Acute Unit. All unit costs related to the financial year 2015–2016.

Statistical methods

Because some of the data were skewed, non-parametric tests were employed where required. Pre–post service use data were reported descriptively and analyzed using comparisons of independent samples. For continuous dependent variables, the tests included t-tests, robust Welch t-tests for non-equal variances, or non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-tests for excessively skewed data as required, and Chi-square tests of independence were employed for categorical dependent variables. In order to avoid violation of the χ2 expected count assumption, ICD codes with expected counts less than five, including F00–F09, F10–F19, F40–F49, F50–F59, F60–F69, F80–F89, and F99–F99, were collapsed into one category. Spearman correlation analyses were applied to determine factors that likely relate to the number of admissions and length of stay following PARC exit. Non-parametric Wilcoxon tests were conducted to compare average length of stay, and reduction in length of stay prior to and after PARC admission, based on number of visits. A non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was conducted to determine whether the reduction in length of stay was related to any particular diagnosis. The threshold for statistical significance was p < 0.05. To derive the mean cost per person, the cost per-bed day at the CHHHS Psychiatric Adult Acute Unit (in 2015–2016 AU$) was multiplied by the total length of stay 6 months preceding study entry and 6 months following study exit. Bootstrap resampling (10,000 draws) was applied to test robustness of the results by estimating 95% confidence intervals for the mean cost and mean change in cost, where the sampling unit for the bootstrap was the person. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 24 (Chicago, IL: SPSS Inc., 2016) and Microsoft Excel (2013).

Ethics

This study is a quality assurance activity and was granted an exemption from ethical clearance by the Far North Queensland Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/15/QCH/108 – 1006 QA).

Results

Sample characteristics

A total of 192 PARC residents experiencing 243 episodes of care were included in the study. On average, the PARC service supported 11 people or 14 episodes of care per month. Of the 192 persons, 112 (58.3%) were male. Ages ranged from 18–72 years (M = 39.3, SD = 12.7, median = 38).

The most commonly reported condition was schizophrenia, schizotypal, and delusional disorders (n = 93, 48.4%), followed by mood (affective) disorders (n = 58, 30.2%), neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders (n = 13, 6.8%), disorders of adult personality and behavior (n = 11, 5.7%), and mental and behavioral disorders due to psychoactive substance use (n = 9, 4.7%). A small number of respondents were also admitted for organic, including symptomatic, mental disorders (n = 3, 1.6%), behavioral syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors (n = 2, 1.0%), disorders of psychological development (n = 1, 0.5%), or unspecified mental disorders (n = 2, 1.0%).

Length of stays at the PARC facility is listed in . The majority (n = 151, 78.6%) had a single stay at PARC during the observed period, and the remainder had two (n = 32, 16.7%), three (n = 8, 4.2%) or four (n = 1, 0.5%) stays. Length of stay did not differ significantly over the first two (Wilcoxon Z = –0.98, p = 0.326) or three (Wilcoxon Z = –5.60, p = 0.575) stays. No test of significance could be conducted for four stays, as only one patient stayed four times.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for length of stay in PARC by number of stays during the study period between May 2015 and July 2016 (inclusive).

No significant differences were observed between those who stayed at PARC for a single stay compared to multiple stays in terms of gender (χ2(1, n = 192) = 0.00, p = 0.976), age (t(190) = 0.14, p = 0.888), primary diagnosis (χ2(4, n = 192) = 8.17, p = 0.086), length of stay (Mann-Whitney U = 2,967, Z = –0.40, p = 0.682), or destination after index PARC admission (χ2(1, n = 192) = 3.67, p = 0.055).

Cost per-bed day

Using activity based funding pricing data, the average cost of an inpatient psychiatric admission was estimated at $1,521 in 2015–2016 dollars. The per-diem cost of the PARC facility was derived by dividing the total annual residential care budget for 2015–2016 by the average number of bed-days per resident, and estimated at $354. The difference in the cost per-bed day at PARC vs psychiatric inpatient unit was derived at $1,167.

Hypothesis testing

Hypothesis 1: PARC was associated with a reduction in number of psychiatric inpatient admissions

Mean number of admissions and number of days admitted to hospital 6 months preceding study entry (before PARC), during, and 6 month following study exit (after PARC) are provided in . Single stay residents had significantly fewer psychiatric admissions over 6 months following study exit (Wilcoxon Z = –4.21, p < 0.001); but not multiple stay residents (Wilcoxon Z = –1.39, p = 0.165). Averaged over both groups (single and multiple stays), the number of hospital admissions after PARC was significantly different to the number of hospital admissions before PARC (Wilcoxon Z = –4.40, p < 0.001).

Table 2. Mean (and SD) number and length of admissions prior to, between, and after PARC admissions.

Hypothesis 2: PARC was associated with a reduction in the length of psychiatric inpatient admissions

In terms of number of days admitted, a significant reduction was observed when averaging over single and multiple stay residents (Wilcoxon Z = –5.21, p < 0.001). When examining this effect by group, the result was only statistically significant for single stays (Wilcoxon Z = –4.95, p < 0.001), but not for multiple stay patients (Wilcoxon Z = –1.84, p = 0.065); however, the interaction effect for reduction in number of days admitted by group was not statistically significant (Mann-Whitney U = 2,966, Z = –0.412, p = 0.680) ().

Hypothesis 3: PARC residents were more likely to be readmitted to the facility from the community (stepping up) vs inpatient psychiatric unit (stepping down)

Patients could enter PARC after being discharged from the hospital (stepped down) or from the community (stepped up). Of those who had a single stay at PARC, 62.9% were discharged from the hospital, as were 46.3% of multiple stay residents for their first stay. provides details about entry destination to PARC, either stepping up or down.

Table 3. Entry destination to PARC by number of stays.*

Table 4. The reduction in number of days admitted to hospital after PARC for each diagnosis.

Of interest to the PARC personnel was whether residents were significantly more likely to step-up rather than step-down for their second visit to PARC. We tested this in two ways. First, a Chi-square goodness-of-fit test comparing the proportion of those stepping up vs stepping down on their second visit indicated that there was no significant difference between the proportion stepping up or down (χ2(1, n = 41) = 2.95, p = 0.086). Second, for those who had multiple stays, we compared the proportion stepping up for their first stay (46.3%) compared to their second (36.6%), using a McNemar test. The difference between stepping down or up on their second visit was not statistically significant (OR, 95% CI = 0.60–6.64, p = 0.388).

A difference variable was created to calculate the reduction in number of days admitted to hospital after PARC, compared to before. Those who experienced a significant reduction in number of days admitted were significantly more likely to stay in PARC for longer on their first visit (Spearman rho = 0.16, p = 0.024), and to have had more admissions and more days admitted prior to PARC (Spearman rho = 0.52, p < 0.001 and Spearman rho = 0.69, p < 0.001, respectively). Those who stepped up from the community for their first stay did not experience a significant reduction in number of days admitted (Mdifference = –2.8, SD = 27.2, t(77) = –0.93, p = 0.355), while those who stepped down from the hospital for their first stay experienced a significant reduction in number of days admitted afterwards (Mdifference = 15.9, SD = 32.8, t(113) = 5.17, p < 0.001), and the difference between the groups was statistically significant (Welch t(182.87) = –4.31, p < 0.001).

Hypothesis 4: There was a difference in the length of subsequent inpatient admissions following index PARC stay by the type of diagnoses

Table 4 shows the reduction in number of days admitted to hospital after PARC for each diagnosis. Overall, the reduction was not significantly different across ICD-10 codes (Kruskal-Wallis H(4) = 2.38, p = .666).

Hypothesis 5: PARC residents incurred a cost reduction in psychiatric admissions

Total costs per resident are reported in . A significant cost reduction was observed for single stay residents (–$14,312, 95% bootstrapped CI = –$21,776 to –$7,031 per resident) and the averaged group (–$12,555, bootstrapped 95% CI = –$19,280 to –$5,680) when 6 months of psychiatric admission costs before the study (or index PARC admission) were compared with 6 months of costs after exiting the study. For multiple stay residents, the cost of subsequent psychiatric readmission was reduced from $33,904, to $24,701 during the study, to $27,821 6 months after leaving the study, but did not result in a significant cost saving (–$6,083, 95% bootstrapped CI = –$21,922–$11,572).

Table 5. Cost per PARC resident 6 months preceding study entry, during, and 6 months following study exit.

Discussion

This study reflects the value of resources used by the PARC service and captures wider systems effects by testing five hypotheses, such as whether introduction of the step-up/step-down service to a far north Queensland region resulted in reduced psychiatric inpatient admissions, shortened average length of stay, and reduced per capita cost of care. This study involved no manipulation of participants or experimental procedures. Rather, it measured and documented what occurred 6 months preceding the study entry, during the study, and 6 months after the study exit in a naturalistic manner using patient activity records. Study participants served as their own control subjects.

Demographics of the service users were similar to the PARC sites in VictoriaCitation12,Citation14,Citation15. Number of stays at PARC was not associated with sex, age, primary diagnosis, PARC index admission destination (such as hospital or community), or length of stay at PARC. This finding suggests that the service is likely to support recovery across a range of conditions.

Lessons learned

People with mental illness generally stay in hospital longer and have high associated costs of careCitation27. Hence, reducing the length of hospital stay by providing an alternative cost-effective care which delivers comparable or improved patient outcomes can have important economic implications. According to our analysis, the cost of 1 day in a psychiatric unit was comparable to an average of five treatment days in PARC.

There is an ongoing debate in the literature as to the validity of a psychiatric inpatient readmission rate as an indicator of hospital or community performanceCitation20,Citation21. One of the main reasons are the risk factors associated with readmissions, such as homelessness, living alone, or being unemployedCitation28. These risk factors are naturally out of the control of health service providers; nonetheless, they may affect the likelihood of readmissions. It is commonly accepted that “readmissions are multifactorial and cover a range of personal, illness, organizational and community issues”Citation20,Citation28. Given this fact, we saw the value in further exploring this issue and contributing to the debate.

Consistent with prior researchCitation9,Citation28,Citation29, we found that complexity of the patients’ health state as measured by a proxy of PARC service use, such as single or multiple stay, was significantly associated with the likelihood of being readmitted to hospital. However, service use is not the only factor. Social, economic, and environmental factors, such as stable housing, employment, support of family and friends, and availability of health services play an important role. Over 80% of the returned PARC residents identified stable accommodation as a need for their recoveryCitation19.

In this study, we did not detect statistically significant differences in the number and length of inpatient admissions for multiple stay PARC residents. There are a number of possible reasons for the lack of association. Multiple stay residents might have experienced more severe functional or emotional decline during the observed period, which resulted in their relapse and readmissions to the facility and back to a hospital psychiatric unit. Readmissions may also happen due to a lack of adherence with outpatient care and medication non-compliance; they may also be a result of unemployment, or simply a lack of accommodation as noted above. An alternative explanation to the lack of a significant reduction in the number and length of inpatient admissions for multiple stay residents is the relatively small sample size (21% of total or 41 residents). At this point, this interpretation is somewhat speculative and necessitates further exploration. Future studies should consider a follow-up with a larger sample over a longer period to ensure statistical power of the results and inclusion of socio-demographics factors. The results for each hypothesis are detailed below.

Hypothesis 1: PARC was associated with a reduction in number of psychiatric inpatient admissions

The study findings partially support the first research hypothesis that PARC was associated with a reduction in the number of inpatient psychiatric readmissions. The overall and within group analyses showed that study participants, on average, and those who had single PARC admission had significantly fewer inpatient readmissions (0.4 fewer admissions), when 6 months data after leaving PARC was compared to 6 months before entering the PARC facility. Further, our analysis did not find that quality of care was compromised by reducing the length of inpatient stay and instead providing recovery care within the community settingsCitation19.

Hypothesis 2: PARC was associated with a reduction in the length of psychiatric inpatient admissions

The second research hypothesis that PARC was contributing to the reduction in the number of days admitted to the hospital was also partially supported. The overall reduction in the average length of stay (8.3 fewer inpatient days), as well as among single PARC stay residents (9.4 fewer inpatient days) was statistically significant and of similar magnitude to the findings of the two previous Australian studiesCitation12,Citation15.

Prior and lengthy admission, intake destination (specifically, stepping down from hospital), and longer stay during index PARC admission were positively associated with the risk of lengthy inpatient stays. This information could be used proactively within step-up/step-down services to target care to the patients most likely to benefit.

Hypothesis 3: PARC residents were more likely to be readmitted to the facility from the community (stepping up) vs inpatient psychiatric unit (stepping down)

The question of whether PARC residents were more likely to be readmitted to PARC from the community (stepping up) vs inpatient psychiatric units (stepping down) requires further examination. The number of those who returned to PARC was too small to draw strong conclusions. It is worth noting that, while the results were inconclusive for general inferences, in this particular sample, residents who returned to PARC were more likely to step up than step down to the facility (46.3% vs 53.7%). The data showed that even more patients returned to PARC from the community vs hospital for their second stay (36.6% vs 63.4%). PARC proved a potential in reaching out to populations with multiple and complex needs, who otherwise might have waited until their health deteriorates and inevitably returned to hospital inpatient treatment. This interpretation is also somewhat speculative and requires further examination.

Hypothesis 4: There was a difference in the length of subsequent inpatient admissions following index PARC stay by the type of diagnoses

Hypothesis 4 results were inconclusive for general inferences and required further examination. However, according to the descriptive analysis, residents with neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders (F40–F48) experienced a greater reduction in number of subsequent inpatient admission (16.3 days), compared to residents diagnosed with schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders (F20–F29) (5.5 days), mood [affective] disorders (F30–F39) (7.4 days), or disorders of adult personality and behaviour (F60–F69) (13.1 days).

Hypothesis 5: PARC residents incurred cost reduction in psychiatric admissions

The findings partially support the last research hypothesis. In the 6 months following PARC exit, single stay residents had significantly fewer (by 0.4 stay) and shorter (by 9.4 days) stays in the psychiatric unit, that resulted in a significant cost reduction ($14,312 per resident) associated with an opportunity cost of improved inpatient flow. The cost reduction for “an average” PARC resident was also statistically significant, $12,555 per resident, when averaged across the single and multiple stay groups. Overall, the introduction of the step-up/step-down community mental health service to the region was associated with significant cost saving equivalent to improved inpatient flow.

Limitations

It should be noted that this analysis was undertaken at a relatively early stage in the implementation and evolution of the PARC service in regional Australia. While some positive short-term associations were demonstrated, long-term follow-up would be required to assess whether the associations maintained and resulted in a sustainable impact. It was not possible to ascertain data on all characteristics that might have influenced the association between the service and the outcome measures. Studying the effect of care transitions on subsequent admissions and length of stay is challenging, because of the thread of reverse causality and confounding by health status. However, statistical techniques were used to adjust for possible confounding. This study utilized administrative records of patients’ admissions and discharges, and, thus, it did not succumb to biases associated with self-report data.

Future follow-up studies are necessary, including those that control for socio-demographics, including indigeneity; history of involuntary admissions; psychosocial functioning and quality-of-life; medications; and stress factors prior to and following index PARC admission. Since this was an observational study, a causal relationship cannot be inferred from the results of this study. An experimental study with alongside economic evaluation of the PARC service, including the impact on productivity losses is warranted.

Conclusion

The research found that the PARC step-up/step-down service, delivered in partnership between a public and non-government mental health service, contributed to transitioning patients from hospital to the community across a range of conditions. More noticeable outcomes were observed among those who stayed in PARC for longer during index admission (rs = 0.16, p = 0.024), who have had more and lengthy inpatient stays (rs = 0.52, p < 0.001 and rs = 0.69, p < 0.001), and those who stepped-down from the hospital (p < 0.001). This information could be proactively used within step-up/step-down services to target care to patients most likely to benefit. Such an approach could be used to address other healthcare areas with capacity constraints; and where services reconfiguration is considered. Efforts should be directed toward the adoption of cost effective alternatives that provide comparable or improved treatment outcomes.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This project was supported by Mind Australia and CQUniversity SHHSS Engaged Research Grant.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

JJ and TW are employees of Mind Australia. The authors report no additional competing interests. The findings and conclusions presented in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Mind Australia or CHHHS. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work, but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (159.7 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge NHMRC Centre for Research Excellence in Integrated Quality Improvement and Cairns and Hinterland Health and Hospital Service (CHHHS) for in-kind support. We deeply appreciate the considerable support, commitment, and contributions of the Cairns PARC team. We acknowledge the following individuals for their contribution to this project: Jade Varcoe, Joe Petrucci, Steve Morton, Catherine Sharpe, John Weaver, Denise Cumming, Heather Thompson, and Margaret Grigg. We thank Lisa Brophy for helpful comments.

References

- Thomas KA, Rickwood D. Clinical and cost-effectiveness of acute and subacute residential mental health services: a systematic review. PS. 2013;64:1140.

- Lloyd-Evans B, Slade M, Jagielska D, et al. Residential alternatives to acute psychiatric hospital admission: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195:109–117.

- Department of Health. Adult prevention and recovery care (PARC) services framework and operational guidelines. Melbourne, Victoria: Mental Health, Drugs and Regions Division; 2010.

- Council of Australian Governments. COAG National Action Plan on Mental Health 2006–2011. Canberra, Australia: COAG; 2006.

- Department of Health and Ageing. National Mental Health Report 2007: Summary of Twelve Years of Reform in Australia’s Mental Health Services under the National Mental Health Strategy 1993–2005. Canberra, Australia: Commonwealth of Australia; 2007.

- Department of Health. Mental health policy. Canberra, Australia: Australian Government; 2017.

- Bruce J, McDermott S, Ramia I, et al. Evaluation of the Housing and Accommodation Support Initiative (HASI) Final Report. Sydney. NSW, Australia: NSW Health and Housing; 2012.

- Jacobson N, Greenley D. What is recovery? A conceptual model and explication. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:482.

- Schon U-K, Denhov A, Topor A. Social relationships as a decisive factor in recovering from severe mental illness. Int J Psychaitry. 2009;55:347.

- Meurk C, Harris M, Wright E, et al. Systems levers for commissioning primary mental healthcare: a rapid review. Australian J Primary Health. 2018;24(1):29–53.

- Department of Health. Stepped care. Canberra: Australian Government; 2016 [cited 2018, March 1]. Available from: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/2126B045A8DA90FDCA257F6500018260/%24File/1PHN%20Guidance%20-%20Stepped%20Care.PDF

- Lee SJ, Collister L, Stafrace S, et al. Promoting recovery via an integrated model of care to deliver a bed-based, mental health prevention and recovery centre. Australas Psychiatry. 2014;22:481–488.

- Kinchin I, Tsey K, Heyeres M, et al. Systematic review of youth mental health service integration research. Aust J Prim Health. 2016;22:304–315.

- Forwood A, Reed C, Reed M, et al. Evaluation of the Prevention and Recovery Care (PARC) Services Project. Melbourne VIC: Dench McClean Carlson; Prepared for Mental Health & Drugs Division Department of Human Services; 2008.

- White C, Chamberlain J, Gilbert M. Examining the outcomes of a structured collaborative relapse prevention model of service in a Prevention and Recovery Care (PARC) Service Phase Two: Research Report. Victoria, Australia: SNAP Gippsland Inc.; 2012.

- Cluff R, Kim S, Egan I. Cairns Hospital in mental health 'crisis': ABC Far North Queensland; 2013 [cited 2016, January 18]. Available from: http://www.abc.net.au/local/stories/2013/09/16/3849701.htm

- Keegan B. Demand for Cairns Hospital mental health unit review: The Cairns Post; 2015 [cited 2016, January 18]. Available from: http://www.cairnspost.com.au/lifestyle/demand-for-mental-health-unit-review/news-story/0b37d2f94af49a21e0f6ca1b1028634b

- Queensland health. Cairns and Hinterland Hospital and Health Service: Queensland Government; 2015 [cited 2016, January 18]. Available from: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/cairns_hinterland/html/about_us.asp

- Heyeres M, Kinchin I, Whatley E, et al. Evaluation of a Residential Mental Health Recovery Service in North Queensland. Front Public Health. 2018;6:123. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2018.00123.

- Callaly T, Hyland M, Trauer T, et al. Readmission to an acute psychiatric unit within 28 days of discharge: identifying those at risk. Aust Health Review. 2010;34:282–285.

- Mark T, Tomic KS, Kowlessar N, et al. Hospital readmission among medicaid patients with an index hospitalization for mental and/or substance use disorder. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2013;40:207–221.

- Sutton M, Garfield-Birkbeck S, Martin G, et al. Economic analysis of service and delivery interventions in health care. Southampton (UK): Health Services and Delivery Research; 2018.

- Sedgwick P. Before and after study designs. BMJ. 2014;349:g5074. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g5074.

- Koshy E, Koshy V, Waterman H. Action research in healthcare. London, UK: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2011.

- Jagosh J, Macaulay AC, Pluye P, et al. Uncovering the benefits of participatory research: implications of a realist review for health research and practice. Milbank Quart. 2012;90:311–346.

- World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems 10th revision. 10th ed. Switzerland: WHO Press; 2011.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Expenditure on specialised mental health services. 2016 [cited 2016, February 4]. Available from: https://mhsa.aihw.gov.au/resources/expenditure/specialised-mh-services/

- Oiesvold T, Saarento O, Sytema S, et al. Predictors for readmission risk of new patients: the Nordic Comparative Study on Sectorized Psychiatry. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101:367–373.

- Psychiatric Disability Services of Victoria. Housing and support: a platform for recovery. 2008 Available from: http://vicserv.org.au/pdf/pathways/paper4.pdf (last accessed 2018 Feb 4).