Abstract

Objectives: There is a lack of data in Panama on the potential differences in total healthcare professional (HCP) time between routine administrations of short-acting erythropoietin simulating agents (ESAs) (i.e. epoetin alfa) and continuous erythropoietin receptor activator (CERA) (i.e. methoxy polyethylene glycol–epoetin beta). This study aimed to quantify the HCP time associated with a single administration of epoetin alfa and CERA for the treatment of anemic patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) on hemodialysis.

Methods: This was a multi-center, cross-sectional study, using a time-and-motion methodology. Costs related to HCP time and consumables usage associated with administration of epoetin alfa and CERA were estimated.

Results: Based on 60 administrations of either CERA or epoetin alfa, the estimated savings in mean total active HCP time were 2.34 (95% confidence interval = 1.87–2.81) min (–30%) per administration. When extrapolating to a full year’s treatment with intravenous ESA, it would require a total of 20.3 (95% CI = 19.90–20.71) h of HCP time for epoetin alfa vs 1.1 (95% CI = 1.01–1.19) h for CERA per patient per year. Estimated savings in active HCP time per patient per year were 19.20 (95% CI = 19.20–19.21) h (–95%). This, in turn, translates into staff cost efficiency that favors Mircera with an estimated annual saving of $78.24 (95% CI = 78.24–78.28) (–95%) per patient.

Conclusions: Data from a real-world setting showed that the adoption of CERA could potentially lead to a reduction in active HCP time.

Few comparative data have explored the costs and potential savings of using long-acting erythropoietin–stimulating agents (ESA) instead of short-acting ESAs to treat anemia in CKD patients on hemodialysis.

This time-and-motion study shows that use of CERA reduces total healthcare professional time and could represent a save for an institution in a real-world setting in Panama.

Highlights

Introduction

The prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) including end-stage renal disease (ESRD, i.e. CKD stage 5 requiring dialysis) was estimated to be 8–16% worldwide in 2013Citation1, and is expected to increase due to an aging populationCitation2. The number of patients being treated for ESRD globally was estimated to be 3.2 million at the end of 2013, of which more than 2.5 million received dialysis treatmentCitation3. Incidence of ESRD increases at a significantly higher annual rate of 6% compared to the global population growth rate of 1.1%Citation3. In Panama, the estimated crude prevalence of CKD was 12% by 2017, and it is considered a major health problem in such a countryCitation4.

Erythropoietin-stimulating agents (ESAs) are standard treatments for renal anemia secondary to CKD in patients undergoing dialysisCitation5. They correct and maintain hemoglobin (Hb) levels within recommended target ranges. Maintaining adequate Hb levels typically requires frequent administration (up to 3-times weekly) of a short-acting ESA, such as epoetin alfa (Epocim) or epoetin beta (NeoRecormon). Previous reports have shown that frequent administration of short-acting ESAs can greatly impact the workload of renal healthcare teamsCitation6. Mircera (methoxy polyethylene glycol-epoetin beta) is a continuous erythropoietin receptor activator (CERA) that has proved to maintain Hb levels within the desired target range when administered once monthly in patients with CKD with or without dialysisCitation7,Citation8.

There are abundant clinical data reporting the benefits of conversion from short-acting ESAs to CERAsCitation9,Citation10. However, few reports have determined the potential annual efficiency gains in terms of time being freed up with the adoption of a long-acting ESA from a short-acting ESA in patients with CKD receiving hemodialysisCitation6,Citation11–13. In typical cost analysis studies, only the drug acquisition expenses are considered in the mathematical modelCitation11–13. However, the real cost of this therapy includes the costs associated with the preparation and administration of each dose, as well as other supplies and consumables needed for the application of each drug. Therefore, in this time and motion study we aimed to quantify the observed Health Care Professional (HCP) time dedicated to ESA administration, and to estimate the costs of labor hours spent by HCPs during this process and consumables usage for the treatment of anemia in patients who underwent hemodialysis for CKD in two Panamanian public centers. Since routine administration of short acting ESA is the standard of care in many centers in Panama, this study also aimed to determine the potential economic benefit of implementing CERA in the management of anemia in chronic hemodialysis patients.

Methods

This was a multi-center (two sites), observational, and cross-sectional study conducted in Panama. Time and motion methodologyCitation14 was used to identify all relevant steps in both epoetin alfa and CERA IV administration processes and collect time actively spent by HCPs on pre-specified ESA administration tasks. Usage of consumables was also recorded. Data on active HCP time were monetized. Patients received hemodialysis and treatments for anemia as per standard of care (SOC) according to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelinesCitation15. Observations of these treatment sessions were performed by independent observers. Chronic hemodialysis patients were eligible if they had been diagnosed with renal anemia secondary to CKD and treated with an ESA as recommended by the treating nephrologist. No exclusion criteria were made depending on iron status, cause of nephropathy, or any other clinical variable.

Data collection

The study was conducted in the outpatient hemodialysis units at two sites in Panama (Complejo Hospitalario (attached to the Social Security), where the SOC for anemic renal patients is epoetin alfa 3-times per week exclusively; and Hospital Santo Tomás (attached to the Ministry of Health), where the SOC is CERA (methoxy polyethylene glycol-epoetin beta) once-monthly exclusively. Data collection occurred between November and December 2017.

Prior to treatment process, HCPs were interviewed at each site to map out the site’s usual ESA administration process into discrete and chronologic tasks including: preparation, distribution, administration, and record keeping (See Supplementary Appendix for details). Personnel were also asked to identify tasks they thought might change if patients were converted from epoetin alfa 3-times weekly (according to manufacturer's recommendation) to a once-monthly methoxy polyethylene glycol-epoetin beta regimen (according to manufacturer’s recommendation), assuming 100% adherence to both therapies and constant doses for each patient. All tasks related to epoetin alfa and CERA administrations were performed by 23 Registered Nurses (RNs) in both centers.

Data were collected during hemodialysis sessions or during shifts, where one or more patients received epoetin alfa or methoxy polyethylene glycol-epoetin beta. Time collected from observations of tasks performed for multiple patients was divided by the number of observed patients to obtain process/task per patient. For the time and motion determination we recorded the time for each phase of the ESA administration process (preparation, distribution, administration, and record keeping) (available as a Supplementary Appendix). A local Contract Research Organization (INDICASAT) was responsible for conducting the observation and data entry into the ClinCapture electronic database by different trained observers.

Statistical analysis

The primary descriptive analysis was time-associated with a single administration of epoetin alfa or methoxy polyethylene glycol-epoetin beta. Mean total active HCP time (composite of mean active HCP time of all pre-specified tasks) was derived based on the observations of total active HCP time per patient. Per individual site/per study drug (since each site utilizes one type of ESA exclusively) data on active HCP time, and consumables usage per ESA administration session were transferred to medical costs using HCP salary data, as well as consumables purchasing costs. Publicly available data from La Gaceta Oficial for HCP salaries and Care Medical Supplies Panamá for consumables were used in the cost estimation of ESA administrationCitation16.

HCP costs were defined by the amount of money earned by each Registered Nurse (RN) per minute during the administration of ESA, assuming 2,496 h worked per year. Costs are expressed in US dollars. Subsequently, time and medical cost per single ESA administration session were multiplied by the anticipated annual administration sessions, assuming 100% adherence to both therapies (expected 156 sessions for Epocim and 12 sessions for Mircera) to yield time and projected cost per patient per year (PPPY) for short-acting epoetin alfa and CERA in a hemodialysis setting. Annual time and costs were also extrapolated to an average site population. Potential time and cost savings (PPPY and per site per year) were calculated as the difference between the study drugs, and the percentage reduction in time was calculated. Given that both therapies are administered intravenously we assumed that flushing IV lines associated costs were equal.

Per individual site/per study drug mean time per pre-specified task, mean total active HCP time, and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI), were calculated using gamma distribution because of the positive skewed distribution characteristics of time data.

The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee of each participating center.

Results

Two Panamanian sites that provide outpatient hemodialysis participated in this study: Complejo Hospitalario (197 attended cases per yearCitation17), which utilized short-acting epoetin alfa exclusively, and Hospital Santo Tomás (203 attended cases per yearCitation17), which utilized methoxy polyethylene glycol-epoetin beta exclusively. Seven nephrologists in Complejo Hospitalario and five specialists in Hospital Santo Tomás were in charge of each hemodialysis unit. The dose of CERA ranged from 100 to 200 µg. Sixty patients (30 in Complejo Hospitalario and 30 in Hospital Santo Tomás) were enrolled into the study. All included patients underwent three hemodialysis sessions per week.

Active HCP times

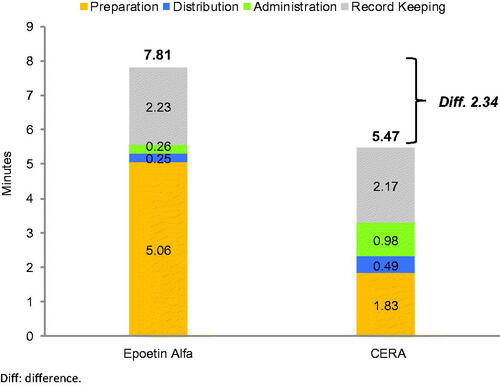

The mean total active HCP time was 7.81 min (95% CI = 7.65–7.97) for a single epoetin alfa administration and 5.47 min (95% CI = 5.05–5.93) for CERA administration. Estimated savings in mean total active HCP time were 2.34 min (95% CI = 1.87–2.81) (–30%) ( and ). The distribution of mean total active HCP time by task is shown in . Preparation time for CERA was 66% lower than for epoetin alfa. Given that epoetin alfa is administered 3-times a week for patients on dialysis, 156 sessions per year are anticipated for patients receiving short-acting epoetin alfa, while 12 monthly sessions per year are anticipated for patients receiving long-acting CERA, assuming 100% adherence. Therefore, a total of 20.3 (95% CI = 19.90–20.71) h and 1.1 (95% CI = 1.01–1.19) h of HCP time would be required, respectively, to treat one patient per year with epoetin alfa and CERA. Estimated savings in active HCP time per patient per year were 19.2 (95% CI = 19.20–19.21) h (–95%) if one switches from epoetin alfa to CERA.

Figure 1. Mean active HCP time per patient per administration by tasks. Abbreviation. Diff, difference.

Table 1. Mean active healthcare professional time (HCP) per patient per session.

Consumables usage

Of a single administration of epoetin alfa, only one syringe was reported; while for CERA one syringe, and two cotton balls were used.

Costs

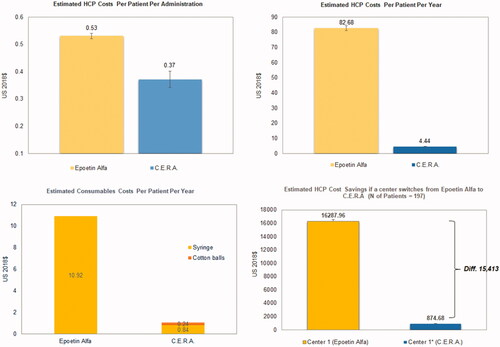

Given the mean total active HCP time was 7.81 min for a single epoetin alfa administration and 5.47 min for CERA administration, and the hourly rate of a registered nurse is ∼$4.08Citation16, the estimated HCP cost for a single administration of epoetin alfa was $0.53 (95% CI = 0.52–0.54), and $0.37 (95% CI = 0.34–0.40) for CERA. When extrapolating to a patient’s yearly ESA treatment (156 applications for epoetin alfa vs 12 applications for CERA), estimated staff costs were $82.68 (95% CI = 81.12–84.24) and $4.44 (95% CI = 4.08–4.80) for epoetin alfa and CERA, respectively (). The estimated savings in annual staff cost were $78.24 (–95%) (95% CI = 78.24–78.28) and attributable to registered nurses exclusively.

Figure 2. Estimated HCP costs per patient per administration (a), HCP costs per patient per year (b), estimated consumables costs during erythropoietin-stimulating agent administration per patient per year (c), and estimated HCP cost savings if a center switches from Epoetin Alfa to CERA for 1 year (US Dollars year 2018).

Consumable costs for a single administration of epoetin alfa and CERA were $0.07 and $0.09, respectively. When extrapolating to the yearly consumption of consumables usage, estimated consumables costs were $10.92 and $1.08 for epoetin alfa and CERA, respectively (). The estimated cost savings in annual consumables usage were $9.84 (–90%), given that 197 patients were treated during 2017 in Complejo Hospitalario (where epoetin alfa is SOC).

Discussion

The present study showed a trend of reduced total active HCP time when comparing methoxy polyethylene glycol–epoetin beta vs epoetin alfa administration. The lack of overlap in the 95% CI (epoetin alfa = 7.65–7.97 vs CERA = 5.05–5.93) may suggest a potentially true difference in active HCP time spent on IV administrations of epoetin alfa and CERA. However, CIs only reflect differences between the two sites that participated, which may not be representative of all sites in Panama; therefore, generalization and interpretation of these results for the whole country need to be done with caution. The estimated unused time and savings show the potential for increasing the capacity of available hemodialysis units with use of CERA instead of epoetin alfa. Additionally, healthcare managers could spend their budget in other relevant tasks and equipment for patient management. Therefore, the incorporation of CERA could contribute to improving the cost-effectiveness of hemodialysis units in Panama.

Although we didn’t take into account the price and dose of each drug in our analysis due to the design of a time and motion study, our findings are in accordance with previous reportsCitation9,Citation11–13. Indeed, previous studies have showed a potential cost reduction when using CERA instead of epoetin alfa in patients with CKD on hemodialysis. For example, Maouujoud et al.Citation11,Citation13 performed a cost-effectiveness analysis to compare epoetin beta vs methoxy polyethylene glycol-epoetin beta and concluded that use of CERA was more cost-effective. Similarly, Gonzalez et al.Citation12 reported superior cost-effectiveness of CERA in Mexican patients with CKD. These previous studies have acknowledged the variability in treatment practices between sites, which may bias the external validity of such resultsCitation6. The external validity of our findings can also be compromised due to the participation of only two centers from Panama. However, we consider that our findings are valuable to determine the potential economic benefit of using CERA instead of short-acting ESA in this particular region.

The reported magnitude of cost reductions (−95%) is higher than the −79% described by Schiller et al.Citation18, who performed a similar time and motion study with these two drugs in five US hemodialysis centers. In accordance with these findings, our study also suggests that HCP time accounts for the larger part of overall costs of ESA treatment. Hence, the incorporation of this drug into standard practice could potentially lower the costs related to the administration of ESA in patients with CKD undergoing hemodialysis. An extrapolation of our findings could potentially save a total of $15,413.28 (95% CI = 15,413.19–15,421.16) in 1 year of treatment with methoxy polyethylene glycol-epoetin beta instead of epoetin alfa ().

However, we must acknowledge that these costs may be overestimated because we assumed a 100% adherence to both hemodialysis sessions and ESA treatment. Moreover, our saving estimates are based on a fixed dose of ESA without taking into account dose changes according to hemoglobin levels and iron status. Despite these caveats, adherence to hemodialysis is considered to be high in the majority of hemodialysis unitsCitation19, and the effect of CERA on hemoglobin levels is usually stable among CKD patientsCitation20.

Our study has some limitations. In terms of study conceptualization, although process mapping was performed prior to the design of observation data collection form, it was not possible to define or control some factors such as systematic bias (in which one site performed one type of ESA administration exclusively) and the Hawthorne effect (“the consequent awareness of being studied, and possible impact on behavior”Citation21). In addition, it is likely that “site” impacts time variables, due to site-specific process flow, the layout of the treatment unit and preparation area, and/or the scope of activities as per usual site standard.

Another potential limitation of this study is the lack of clinical information. Hence, this study was not able to evaluate any potential association between active HCP time and patient characteristics (e.g. age, disease severity, hemoglobin levels, iron profiles, and comorbidities or complications during treatment). However, “patient” variables are expected to be of less importance in time and motion task time measurements due to a discrepancy between what practitioners do and what patients perceive was done, as previous authors suggestedCitation18. Besides, we did not take into account some other relevant clinical variables associated with the interdisciplinary management of anemia in these patients, such as: time spent on laboratory examinations, nutritional and pharmaceutical counseling for patients, and visits to the Emergency Department due to anemia-related complications.

Another source of variability is “measurement-related” in terms of: (1) accounting for all relevant tasks within Epocim and Mircera administrations, and (2) the accuracy of task measurements. We aimed to minimize measurement errors by a thorough evaluation of all tasks by clearly defining the concept of active HCP time, and by developing clear and unambiguous descriptions of each task. To mitigate the inter-observer variability in manual stopwatch measurement, we offered clear and standardized observer training. In terms of data collection and quality control, time data are unique and quickly elapse after observations, making it challenging to retrieve or query a potential problematic time data entry. This was mitigated through a clear quality control algorithm based on early transfer of complete paper case report forms to electronic database.

Despite these caveats, we showed for the first time in a Latin-American country that the adoption of long-acting methoxy polyethylene glycol-epoetin beta (compared to short–acting epoetin alfa) could potentially lead to a reduction in active HCP time of 19.2 h per year. Translating the saved active HCP time into cost could indicate an annual opportunity cost saving of $78.24 for a single patient. From the payers’ perspective, this approach could represent significant time and costs savings as a result of switching from short-acting epoetin alfa to long-acting CERA in a developing country with scarce resources. Further studies may be warranted to confirm the cost-effectiveness of this strategy.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Roche.

Declaration of financial/other interests

D.R., F.R., and A.R. have received grant support from Roche. S.T. received consultancy fees from Roche for her contribution to this work. M.C. is an employee of Roche. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work, but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgements

None reported.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (50.2 KB)References

- Jha V, Garcia-Garcia G, Iseki K. Chronic kidney disease: global dimension and perspectives. Lancet. 2013;382:260–267.

- Tonelli M, Riella M. Chronic kidney disease and the aging population. Am J Nephrol. 2014;39:248–251.

- Fresenius Medical Care. ESRD patients in 2013: a global perspective. Bad Homburg, Germany: Fresenius Medical Care AG & Co. KGaA; 2014.

- Moreno-Velásquez I, Castro F, Gómez B, et al. Chronic kidney disease in Panama: results from the PREFREC study and national mortality trends. Kidney Int Rep. 2017;2:1032–1041.

- KDOQI. National Kidney Foundation. KDOQI clinical practice guidelines and clinical practice recommendations for anemia in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;47:S11–S145.

- De Cock E, Dellanna F, Khellaf K, et al. Time savings associated with CERA once monthly: a time-and-motion study in hemodialysis centers in five European countries. J Med Econ. 2013;16:648–656.

- Carrera F, Lok CE, de Francisco A, et al. Maintenance treatment of renal anaemia in haemodialysis patients with methoxy polyethylene glycol-epoetin beta versus darbepoetin alfa administered monthly: a randomized comparative trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:4009–4017.

- Mann JF, de Francisco A, Nassar G, et al. Fewer dose changes with once-monthly CERA in patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin Nephrol. 2011;76:9–15.

- Cases A, Portolés J, Calls J, et al. Beneficial dose conversion after switching from higher doses of shorter-acting erythropoiesis-stimulating agents to CERA in CKD patients in clinical practice: MINERVA study. Int Urol Nephrol. 2014;46:1983–1995.

- Fliser D, Kleophas W, Dellanna F, et al. Evaluation of maintenance of stable haemoglobin levels in haemodialysis patients converting from epoetin or darbepoetin to monthly intravenous CERA: the MIRACEL study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26:1083–1089.

- Maoujoud O, Ahid S, Dkhissi H, et al. The cost-effectiveness of continuous erythropoiesis receptor activator once monthly versus epoetin thrice weekly for anaemia management in chronic haemodialysis patients. Anemia. 2015;2015:189404.

- Gonzalez P, Gomez E, Vargas J. PSY25 renal anemia (RA) treatment in Mexican public health care institutions: an evaluation of the costs and consequences. Value Health. 2009;12:A379–A380.

- Maoujoud O, Ahid S, Cherrah Y. The cost-utility of treating anemia with continuous erythropoietin receptor activator or Epoetin versus routine blood transfusions among chronic hemodialysis patients. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2016;9:35–43.

- Barnes RM. Motion and time study: design and measurement of work, 7th edn. Wiley; 1980. ISBN: 978-0-471-05905-9

- Mikhail A, Brown C, Williams JA. Renal association clinical practice guideline on anaemia of chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18:345.

- Government of Panama. La Gaceta Oficial. 2015. [cited 2018 Oct 2]. Available from: https://www.gacetaoficial.gob.pa/pdfTemp/27921/GacetaNo_27921_20151203.pdf

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censo. Contraloría General de la República de Panamá. 2016. [cited 2018 Oct 9]. Available from: https://www.contraloria.gob.pa/inec/Publicaciones/Publicaciones.aspx?ID_SUBCATEGORIA=37&ID_PUBLICACION=831&ID_IDIOMA=1&ID_CATEGORIA=5

- Schiller B, Doss S, De Cock E, et al. Costs of managing anemia with erythropoiesis stimulating agents during hemodialysis: a time and motion study. Hemodial Int. 2008;12:441–449.

- Chan KE, Thadhani RI, Maddux FW. Adherence barriers to chronic dialysis in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:2642–2648.

- Sulowicz W, Locatelli F, Ryckelynck JP, et al. Once-monthly subcutaneous CERA maintains stable hemoglobin control in patients with chronic kidney disease on dialysis and converted directly from epoetin one to three times weekly. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:637–646.

- Parsons H. What happened at Hawthorne? New evidence suggests the Hawthorne effect resulted from operant reinforcement contingencies Science. 1974;183:922–932.