Abstract

Aims: Among patients with schizophrenia, poor adherence and persistence with oral atypical antipsychotics (OAA) often results in relapse and hospitalization. Second-generation antipsychotic long-acting injectables (SGA LAI) have demonstrated higher adherence than first-generation antipsychotic LAI and OAA therapies. This study aimed to determine whether SGA LAIs are associated with better persistency compared to OAA among Medicaid recipients with schizophrenia.

Materials and methods: From the MarketScan Medicaid Database (January 1, 2010–June 30, 2016), patients aged ≥18 years with schizophrenia and ≥2 pharmacy claims more than 90 days apart for the same SGA LAI or OAA were selected. New users of the specific antipsychotic agent were classified, based on their index agent, as: OAA, paliperidone palmitate LAI (PPLAI), aripiprazole LAI (ALAI), and risperidone LAI (RLAI). Discontinuation during 1 year of follow-up was defined as a ≥ 60-day gap in the index OAA or SGA LAI medication past the exhaustion of the previous claim’s supply. Inverse probability of treatment weights (IPTW) balanced the cohort characteristics, and weight outliers (<0.1 or >0.9) were excluded. IPTW-weighted Cox proportional hazards regression estimated hazard ratios for discontinuation.

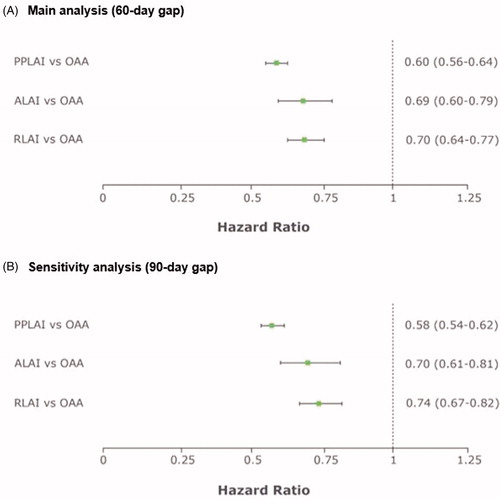

Results: Cohorts included 7,029 OAA, 4,302 PPLAI, 586 ALAI, and 1,456 RLAI patients. Mean age was 38.0–41.0 years and 44.0–46.6% were female. Persistence was significantly longer in the SGA LAI cohorts than in the OAA cohort. Adjusted hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) for discontinuation were 0.60 (0.56–0.64) for PPLAI, 0.69 (0.60–0.79) for ALAI, and 0.70 (0.64–0.77) for RLAI vs OAA.

Limitations: Results may not be generalizable to patients covered by commercial or Medicare insurance, and limitations inherent to any claims-based retrospective analysis apply.

Conclusions: SGA LAI may be a valuable option for treating schizophrenia given the improvement in persistence.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a chronic and complex neurodevelopmental disorder with a range of symptoms categorized as positive (e.g. delusions, hallucinations, thought disorders), negative (e.g. flat affect, difficulty beginning and switching activities), and cognitive (e.g. ability to understand information and use it to make decisions, trouble focusing)Citation1,Citation2. Estimates of prevalence in the US range from 0.25–0.64%Citation3,Citation4, and most of these patients are insured by MedicaidCitation5. Schizophrenia is characterized by alternating periods of full or partial remission and frequent relapsesCitation1,Citation6. Most patients have a relapse after the first episode, and there is often cognitive decline and the occurrence of negative symptoms, worsening the course of illnessCitation1,Citation6. Relapse prevention is a primary focus of treatment with antipsychotic medications and, with sustained remission, patients can have symptom control and improved vocational and social functioningCitation6–8. Poor compliance or discontinuation of therapy have been shown to lead to relapses and hospitalizationsCitation9–11. Functional capability and skills used in everyday life are important factors impacting schizophrenia treatment adherenceCitation12,Citation13.

Second-generation antipsychotic long-acting injectables (SGA LAI) offer an alternative treatment option to oral antipsychotics (OAA). SGA LAI are administered by a healthcare professional and require a less frequent administration (biweekly, monthly, or every 3 months) compared to OAACitation14–18. Additionally, SGA LAI have been shown to reduce hospitalizations compared with OAACitation19–21. SGA LAI have been included in some guidelines for treatment of the first psychotic episode and have been particularly recommended for those with frequent relapses and poor adherence as they offer improved tolerability compared to OAA and first-generation antipsychotic long-acting injectablesCitation22,Citation23. A systematic review of studies of the reasons for poor adherence found that the most common reason was lack of insight, specifically awareness of the need for treatment and awareness of the disorder, in addition to other reasons such as substance abuse, a negative attitude towards taking medication, side-effects, cognitive impairment, quality of the relationship with the physician, and family supportCitation24. A literature review has demonstrated that SGA LAI have an advantageous profile of efficacy, safety, and tolerability, thus a potential for improved adherenceCitation25,Citation26. LAI have also shown a beneficial impact on recovery of psychosocial functionCitation27.

Real-world evidence is needed on the length of continuation of antipsychotic therapy with SGA LAI. The objective of this study was to examine the time to discontinuation of SGA LAI compared to OAA in patients with schizophrenia covered under Medicaid.

Methods

Data source and time frame

This retrospective longitudinal cohort study used US administrative healthcare claims data from the IBM Watson Health MarketScan Multi-State Medicaid Database from January 1, 2009 through June 30, 2017. The patient selection timeframe was January 1, 2010 through June 30, 2016. Patients were followed for a 12-month fixed post-index period, and covariates were assessed during a 12-month baseline period.

The MarketScan Multi-State Medicaid Database contains longitudinal records of inpatient and outpatient services and prescription drug claims for Medicaid enrollees in geographically-dispersed states, including 8.2 million people in 2016. All database records are de-identified and fully compliant with US patient confidentiality requirements set forth in Sections 164.514 (a)–(b)1ii of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regarding the determination and documentation of statistically de-identified data. Because this study used only de-identified patient records and did not involve the collection, use, or transmittal of individually identifiable data, Institutional Review Board approval was not necessary.

Patient selection

Patients aged ≥18 with ≥2 claims indicative of the same SGA LAI or with ≥2 claims indicative of the same OAA within 90 days of each other during the period January 1, 2010 through June 30, 2016 were selected. The index date was the date of the first of the two either SGA LAI or OAA claims. Study treatments of interest included aripiprazole, asenapine, clozapine, iloperidone, lurasidone, olanzapine, olanzapine/fluoxetine, paliperidone (monthly or every 3 months), quetiapine, risperidone, ziprasidone. SGA LAI were identified on outpatient claims using Healthcare Common Procedure Codes (HCPCS) and on pharmacy claims using National Drug Codes (NDC). OAA were identified on pharmacy claims using NDC codes. Patients were required to have at least 12 months of continuous Medicaid enrollment with medical and pharmacy benefits during both the 12-month baseline and 12-month post-index periods. All patients had ≥1 inpatient claim or ≥2 outpatient medical claims with a diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-9-CM 295.xx or ICD-10-CM F20.x) between January 1, 2010 and June 30, 2016, including one during the baseline period. Patients were assigned to the OAA or SGA LAI cohorts based on their index treatment. The SGA LAI cohort was divided into three sub-cohorts: paliperidone palmitate LAI (PPLAI), aripiprazole LAI (ALAI), and risperidone LAI (RLAI).

Patients were excluded if they had any claim for their index agent during the baseline period. Patients in the OAA cohort were excluded if they had any claim for an SGA LAI during the 12-month post-index period. This study focused on PPLAI, ALAI, or RLAI as index SGA LAI.

Outcome

The study outcome was the number of days from the index date until discontinuation of the index agent. Discontinuation was defined as the lack of subsequent claims for the index medication for ≥60 days following the exhaustion of the previous claim’s “days’ supply”. An additional sensitivity analysis used a 90-day gap rather than a 60-day gap to define discontinuation. Days’ supply is provided on pharmacy claims along with the drug’s NDC code. When injectable drugs are billed by a provider, HCPCS codes are used and days’ supply is not available. When days’ supply was not provided on the drug claim, the days’ supply was assigned using the dosing information on the drug product label, as shown in the product label ().

Table 1. Assigned days’ supply for LAI anti-psychotics.

Covariates

Patients’ age, gender, insurance plan type, and race were assessed on the index date. Comorbidities, the Deyo-Charlson Comorbidity IndexCitation28, and the number of unique mental health diagnoses (at the 5-digit ICD-9-CM level and 6-digit ICD-10 level) were assessed during the baseline period using ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM codes. The use of antipsychotic agents and concomitant mental health medications were assessed during the baseline period using pharmacy and medical claims ().

Table 2. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the final IPTW-weighted cohorts.

Statistical analyses

Inverse probability of treatment weights (IPTW) were used to help balance the characteristics across the cohortsCitation29–31. The purpose of this technique was to ensure that the observed differences in the outcome were due to drug treatment rather than confounding factors. A multinomial logistic regression model estimated the probability that a patient would be treated with PPLAI, ALAI, RLAI, or OAA. The estimated probabilities were used to compute the weights. Patients with weight outliers (<0.1 or >0.9) were excluded to achieve balance across cohorts (i.e. standardized difference <10). Kaplan-Meier curves were created to visually inspect the differences in time to discontinuation between the three SGA LAI cohorts and the OAA cohort. An IPTW-weighted Cox proportional hazards model was estimated for days to discontinuation, controlling for the baseline demographic, clinical, and medication characteristics listed in as well as inpatient admissions, emergency room visits, outpatient visits, and total healthcare costs during the baseline period.

Results

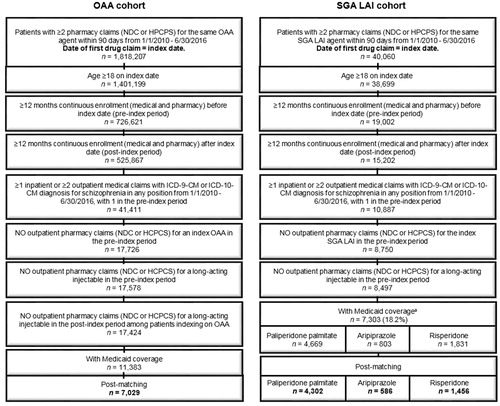

A total of 11,383 OAA and 7,303 SGA LAI patients initially met the selection criteria in the Medicaid database. After the exclusion of patients with weight outliers, there were 7,029 OAA, 4,302 PPLAI, 586 ALAI, and 1,456 RLAI patients included in the analyses (). The mean age was 38.0–41.0 years and 44.0–46.6% were female. The mean comorbidity burden, as measured by the Deyo-Charlson Comorbidity Index, was slightly higher for SGA LAI than for OAA (OAA: 0.7, PPLAI: 0.8, ALAI: 0.8, RLAI: 0.9). The most common baseline comorbidities were cardiovascular disease (OAA: 40.4%, PPLAI: 41.9%, ALAI: 42.9%, RLAI: 47.7%), hypertension (35.2%, 36.4%, 37.2%, 41.5%), and substance abuse (31.2%, 34.1%, 32.3%, 34.8%). The number of unique mental health diagnoses ranged from 3.8–4.7, with OAA patients having the lowest number ().

Figure 1. Patient selection. aSeventy-two patients with LAI other than paliperidone palmitate, aripiprazole, and risperidone were excluded due to small sample size. Abbreviations. HCPCS, Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System; ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; ICD-10-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification; LAI, Long-acting injectable, NDC, National Drug Codes; OAA, Oral atypical antipsychotics, SGA, Second generation antipsychotics.

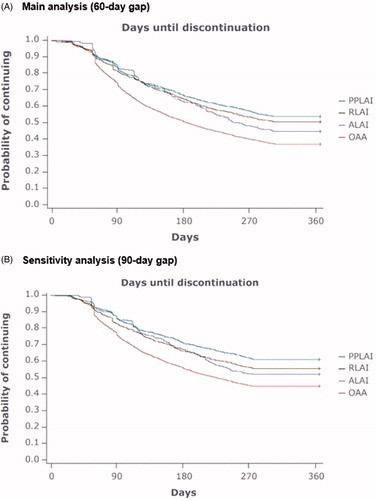

Kaplan-Meier curves showed a significant difference in the time to discontinuation between the OAA cohort and each of the SGA LAI cohorts in both the main analysis (60-day gap) and sensitivity analysis (90-day gap) (). The log rank test for the significance of a difference among all cohorts had a p < 0.001. The probability of discontinuing was similar among the three SGA LAIs for the first 180 days. However, beyond 180 days, PPLAI maintained the lowest probability of discontinuation among the three SGA LAIs in both the main analysis and the sensitivity analysis.

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier curves for time to discontinuation of antipsychotic therapy. Abbreviations. ALAI, Aripiprazole LAI; LAI, Long-acting injectable; OAA, Oral atypical antipsychotics; PPLAI, Paliperidone palmitate LAI; RLAI, Risperidone LAI.

Results of the IPTW-weighted regression model showed that, compared to the OAA cohort, patients on SGA LAI had a significantly lower hazard ratio of discontinuing therapy (95% confidence intervals in parentheses): 0.60 (0.56–0.64) for PPLAI, 0.69 (0.60–0.79) for ALAI, and 0.70 (0.64–0.77) for RLAI (p < 0.05 in all comparisons) (). Results of the sensitivity analysis were consistent.

Discussion

This study found that patients with schizophrenia who initiated an SGA LAI had significantly lower risk of discontinuation during 1 year of follow-up than those who initiated an OAA, as evidenced by significantly lower hazard ratios of discontinuing therapy.

Improved persistence has been reported for SGA LAI compared with OAA in other studies conducted in Medicaid claims databases. One study found that patients who initiated LAI were 20% less likely to discontinue after 1 year than those who initiated an oral antipsychoticCitation32. Another reported that patients initiating SGA LAI had higher odds of continuing during a year than those initiating OAA. The odds ratios were 1.24 (1.13–1.36), 1.45 (1.33–1.58), and 1.39 (1.28–1.51) for defined gaps of ≥30, ≥60 and ≥90 days, respectively. As with our study, the examination of three SGA LAIs separately found that PPLAI had the highest odds of continuing when persistence was defined using a gap of ≥60 or ≥90 days. When using claims data to study medications that are administered by intramuscular injections that must be delivered by a healthcare provider, improved persistence observed via claims translates to actual patient behavior, since a patient must show up to a pharmacy or physician’s office to receive an additional injection. The injectable nature of SGA LAI presents an opportunity for the provider to connect with the patient to discuss any potential issues with effectiveness and tolerability, encouraging continued persistence with the medication. The benefit of more frequent interaction with a healthcare professional is supported by other investigations comparing SGA LAI to OAA.

In addition to our finding that SGA LAIs have improved persistence, several studies have shown that adherence to the dosing schedule is also better with LAI than with OAACitation17,Citation19,Citation32–35. Together, the improved adherence and persistence with antipsychotic medications are expected to lead to improved outcomes, particularly a reduction in the rate of relapse. This improvement has been shown to be the case in studies that use real world data and have found that the use of LAI reduces the rate of all cause hospitalization and schizophrenia-related hospitalization. Pesa et al.Citation20 found that Medicaid patients treated with PPLAI had statistically significant lower risks of all-cause and mental health-related hospitalization compared with OAA (36% and 38%, respectively). Another study of commercially-insured patients found that all-cause and schizophrenia-related hospitalizations were reduced more after patients initiated LAI than OAACitation21. These findings were echoed in an investigation conducted by MacEwan et al.Citation36 where Medicaid patients who received an LAI were much less likely to have a re-hospitalization in 60 days post-discharge than patients who received an OAA. Similarly, a different analysis of Medicaid enrollees who received a first-generation antipsychotic (FGA) LAI or a SGA LAI after a schizophrenia-related hospitalization found that only patients who received a SGA LAI had a significant reduction in the odds of re-hospitalization in 6 months compared with OAACitation19.

Both improved adherence and lower hospitalization rates support early treatment with SGA LAI. In addition, it has been shown that SGA LAI may improve neuroplasticity, prevent neurodegenerationCitation37–39, and reduce substance abuse or misuseCitation40,Citation41.

Our study is subject to a number of limitations. It was conducted using Medicaid data. While it is the source of the majority of data on schizophrenia patients in the US, it may not be reflective of the behavior of commercially-insured patients who are more likely to have a higher socioeconomic status. The study required two injections or two dispensed prescriptions of antipsychotics; hence, by design, patients who discontinued after one administration of the drug were not included. Due to the nature of the insurance claims data, there is uncertainty whether the patients who were dispensed the oral medications actually consumed these medications and when they took them, while the data on the injectable medications has much more precise timing provided by the date of the injection. There was also no information on the reasons for discontinuation. It should also be noted that a switch to a different antipsychotic was considered to be a discontinuation, so some patients who “discontinued” may still have been covered by another antipsychotic. As in other studies using naturalistic data, patients cannot be randomly assigned to one treatment or another. It is possible that patients may have been channeled to orals or LAI based on factors that could also be related to the outcome. For example, LAI may be prescribed particularly to patients who have been known to have adherence problems in the past. In this study, we adjusted for potential bias using IPTW methods, including removing a large number of outliers so that we could compare the LAI patients with the most similar OAA patients. A higher percentage of outliers were removed from the other cohorts (ALAI, RLAI, and OAA) than from the PPLAI cohort, which may also reflect the possibility that physicians prescribed drugs based on patients’ characteristics that are potential predictors of efficacy and adherence. In addition, OAA patients in general had lower rates of baseline comorbidities and lower rates of medication use than LAI patients, even after IPTW weighting. This low severity proxy of health status combined with the highest discontinuation rate seemed to suggest a correlation of disease severity and adherence. Future research will be needed to better understand this relationship. A study with a time frame longer than 1 year could provide additional useful information about persistence. Finally, due to the lack of information on safety and tolerability in claims data, their impact on persistence could not be examined in this study.

Conclusion

Within a population of Medicaid recipients with schizophrenia, overall SGA LAI (PPLAI, ALAI, and RLAI) users had a significantly lower risk of discontinuing therapy than OAA users. PPLAI users had a numerically lower risk of discontinuing therapy than ALAI and RLAI users when all were compared to OAA users. This study demonstrates that SGA LAI therapy for treating schizophrenia represents a valuable tool in increasing persistence on medication.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This work was supported by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. This study was conducted by IBM Watson Health, USA.

Declaration of financial/other interests

XS, MB, and DS are employees of IBM Watson Health which received compensation from Janssen for the overall conduct of the study and preparation of this manuscript. ACEK and KJ are employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC and stockholders of Johnson & Johnson, Co. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work. In addition, a reviewer on this manuscript declares working for a company that co-markets one of the comparators in this manuscript. The reviewers have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Acknowledgements

Programming for this manuscript was conducted by Puja A. Bishwal and Aswin Kalyanaraman. Editorial/medical writing assistance for the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Suellen Curkendall. The study was funded by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

References

- Lieberman JA. Is schizophrenia a neurodegenerative disorder? A clinical and neurobiological perspective. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:729–739.

- National Institutes of Mental Health. Schizophrenia overview. 2016. [cited 2018, September 19]. Available from: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/schizophrenia/index.shtml

- National Institutes of Mental Health. Schizophrenia statistics. 2018. [cited 2018, September 19]. Available from: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/schizophrenia.shtml

- Simeone JC, Ward AJ, Rotella P, et al. An evaluation of variation in published estimates of schizophrenia prevalence from 1990 horizontal line 2013: a systematic literature review. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:193.

- Khaykin E, Eaton WW, Ford DE, et al. Health insurance coverage among persons with schizophrenia in the united states. PS. 2010;61:830–834.

- Muller N. Mechanisms of relapse prevention in schizophrenia. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2004;37(Suppl 2):S141–S147.

- Kane JM. Treatment strategies to prevent relapse and encourage remission. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(Suppl 14):27–30.

- American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. 2nd ed. 2004. [cited 2018, September 19]. Available from: http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/schizophrenia.pdf

- Leucht S, Barnes TR, Kissling W, et al. Relapse prevention in schizophrenia with new-generation antipsychotics: a systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1209–1222.

- Simpson GM. Atypical antipsychotics and the burden of disease. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11:S235–S241.

- Leucht S, Tardy M, Komossa K, et al. Antipsychotic drugs versus placebo for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379:2063–2071.

- Galderisi S, Rucci P, Kirkpatrick B, et al. Interplay among psychopathologic variables, personal resources, context-related factors, and real-life functioning in individuals with schizophrenia: a network analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:396–404.

- Iasevoli F, Giordano S, Balletta R, et al. Treatment resistant schizophrenia is associated with the worst community functioning among severely-ill highly-disabling psychiatric conditions and is the most relevant predictor of poorer achievements in functional milestones. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2016;65:34–48.

- Otsuka Pharmaceutical. Abilify Maintena® (aripiprazole) package insert. Revised March 2018 [cited 2018, September 19]. Available from: https://www.otsuka-us.com/media/static/Abilify-M-PI.pdf?_ga=2.215623319.1485705347.1537414018-937491225.1537414018

- Janssen Pharmaceuticals. Invega Sustenna® (paliperidone palmitate) package insert. Revised July 2018 [cited 2018, September 19]. Available from: http://www.janssenlabels.com/package-insert/product-monograph/prescribing-information/INVEGA+SUSTENNA-pi.pdf

- Janssen Pharmaceuticals. Invega Trinza® (paliperidone palmitate) package insert. Revised July 2018 [cited 2018, September 19]. Available from: http://www.janssenlabels.com/package-insert/product-monograph/prescribing-information/INVEGA+TRINZA-pi.pdf

- Pilon D, Joshi K, Tandon N, et al. Treatment patterns in Medicaid patients with schizophrenia initiated on a first- or second-generation long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotic. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:619–629.

- Janssen Pharmaceuticals. Risperdal Consta® (risperidone) package insert. Revised July 2018 [cited 2018, September 19]. Available from: http://www.janssenlabels.com/package-insert/product-monograph/prescribing-information/RISPERDAL+CONSTA-pi.pdf

- Marcus SC, Zummo J, Pettit AR, et al. Antipsychotic adherence and rehospitalization in schizophrenia patients receiving oral versus long-acting injectable antipsychotics following hospital discharge. JMCP. 2015;21:754–768.

- Pesa JA, Muser E, Montejano LB, et al. Costs and resource utilization among Medicaid patients with schizophrenia treated with paliperidone palmitate or oral atypical antipsychotics. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2015;2:377–385.

- Offord S, Wong B, Mirski D, et al. Healthcare resource usage of schizophrenia patients initiating long-acting injectable antipsychotics vs oral. J Med Econ. 2013;16:231–239.

- Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, et al. Strategies for addressing adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness: recommendations from the expert consensus guidelines. J Psychiatr Pract. 2010;16:306–324.

- Llorca PM, Abbar M, Courtet P, et al. Guidelines for the use and management of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in serious mental illness. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:340.

- Velligan DI, Sajatovic M, Hatch A, et al. Why do psychiatric patients stop antipsychotic medication? A systematic review of reasons for nonadherence to medication in patients with serious mental illness. PPA. 2017;11:449–468.

- Orsolini L, Tomasetti C, Valchera A, et al. An update of safety of clinically used atypical antipsychotics. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016;15:1329–1347.

- De Berardis D, Marini S, Carano A, et al. Efficacy and safety of long acting injectable atypical antipsychotics: a review. CCP. 2013;8:256–264.

- Olagunju AT, Clark SR, Baune BT. Long-acting atypical antipsychotics in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analyses of effects on functional outcome. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2019.

- Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with icd-9-cm administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619.

- Hirano K, Imbens GW. Estimation of causal effects using propensity score weighting: an application to data on right heart catheterization. Health Serv Outcomes Res Methodol. 2001;2:259–278.

- Kurth T, Walker AM, Glynn RJ, et al. Results of multivariable logistic regression, propensity matching, propensity adjustment, and propensity-based weighting under conditions of nonuniform effect. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:262–270.

- Curtis LH, Hammill BG, Eisenstein EL, et al. Using inverse probability-weighted estimators in comparative effectiveness analyses with observational databases. Med Care. 2007;45:S103–S107.

- Greene M, Yan T, Chang E, et al. Medication adherence and discontinuation of long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. J Med Econ. 2018;21:127–134.

- Pilon D, Tandon N, Lafeuille MH, et al. Treatment patterns, health care resource utilization, and spending in Medicaid beneficiaries initiating second-generation long-acting injectable agents versus oral atypical antipsychotics. Clin Ther. 2017;39:1972–1985. e2.

- Kaplan G, Casoy J, Zummo J. Impact of long-acting injectable antipsychotics on medication adherence and clinical, functional, and economic outcomes of schizophrenia. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2013;7:1171–1180.

- Lin J, Wong B, Offord S, et al. Healthcare cost reductions associated with the use of LAI formulations of antipsychotic medications versus oral among patients with schizophrenia. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2013;40:355–366.

- MacEwan JP, Kamat SA, Duffy RA, et al. Hospital readmission rates among patients with schizophrenia treated with long-acting injectables or oral antipsychotics. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67:1183–1188.

- Chen AT, Nasrallah HA. Neuroprotective effects of the second generation antipsychotics. Schizophr Res. 2019;pii:S0920-9964(19)30134-3.

- Diamond G, Siqueland L. Current status of family intervention science. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2001;10:641–661.

- McCormick L, Decker L, Nopoulos P, et al. Effects of atypical and typical neuroleptics on anterior cingulate volume in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2005;80:73–84.

- Rubio G, Martínez I, Ponce G, et al. Long-acting injectable risperidone compared with zuclopenthixol in the treatment of schizophrenia with substance abuse comorbidity. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51:531–539.

- Koola MM, Wehring HJ, Kelly DL. The potential role of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in people with schizophrenia and comorbid substance use. J Dual Diagn. 2012;8:50–61.