Abstract

Aims: To assess patient and disease characteristics, treatment patterns, and associated costs in patients with advanced or metastatic gastric cancer (A/MGC) in Colombia, in both the public and private hospitals.

Materials and methods: A total of 145 patients who had received first-line chemotherapy treatment (platinum analog and/or a fluoropyrimidine) and were followed for at least 3 months after the last administration of a first-line cytotoxic agent were eligible for inclusion. Case-report forms were elaborated based on the patients’ medical records from three Colombian hospitals. Estimates of treatment costs were calculated using unit costs from the participating hospitals.

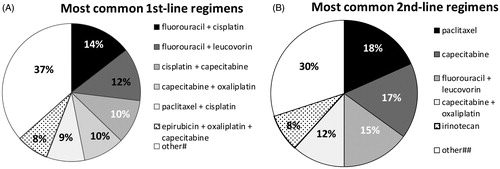

Results: Of the 145 patients, more than half (64.83%) were male, 79.56% were diagnosed with metastatic stage IV disease (mean age = 58.14 years). Prior to MGC diagnosis, 31.71% of the patients being operated on received a total gastrectomy; 66.9% of the patients received a doublet therapy, of which 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) in combination with cisplatin was the standard treatment (14%), followed by combination with leucovorin (12%). Only around 10% of the patients responded to first-line treatment. Out of 41.38% of the patients who received a second-line treatment, 71.67% were still administered a platinum analog and/or fluoropyrimidine. During the follow-up period, 52% of the patients progressed and 20% achieved stable disease. Best supportive care mostly consisted of outpatient visits after last line-therapy (72.41%), palliative radiotherapy (18.6%), and surgery (37.2%).

Limitations and conclusions: Gastric cancer is one of the main causes of cancer-related death in Colombia, as most of the patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage, when prognosis is poor. Treatment patterns are highly heterogeneous. Second-line treatments were mostly initiated with paclitaxel, capecitabine, irinotecan, or cisplatin.

Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) is the fifth most common malignancy worldwide, and ranks third in mortality among all cancersCitation1. Since the mid-1970s, when stomach cancer was the most common cause of neoplasm, its incidence rates have steadily declined in many parts of the world, possibly due to an improvement in food preservation, the availability of fresh fruit and vegetables, and the decrease in the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and smoking habitsCitation2,Citation3. Epidemiological data among countries is very heterogeneous, with the highest incidence rates seen in South America and Eastern Asia, and the lowest in North America and most of AfricaCitation4.

In Colombia, stomach cancer is the fourth most common cancer (after prostate, breast, and cervical cancers), but it is one of the top cancer-related causes of deathCitation2,Citation5,Citation6. There are also gender differences in GC incidence rates, affecting 23.4 males and 12.5 females per 100,000 populationCitation2. In Colombia, GC incidence and mortality increases with altitude in the mountainous regions along the Pacific rim, probably as a consequence of several risk factors that may cluster together in these regions (genetic, dietary, and environmental factors, as well as prevalence of more or less aggressive H. pylori strains)Citation7. Age is another risk factor, as it has been noted that gastric adenocarcinoma occurs most frequently between the ages of 55 and 80, and that it is rare in patients younger than 30Citation2.

Stomach tumors are a group of heterogeneous malignant lesions in terms of structure, growth pattern, cellular differentiation, and histogenesisCitation8. More than 95% of them are adenocarcinomas and, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) system, they may be categorized into five histological subtypes: adenocarcinoma (intestinal or diffuse), papillary, tubular, mucinous, and signet-ring cellCitation8. An alternative classification, the Láuren classification system, divides GC into two major histological types: intestinal or diffuse, on the basis of microscopic configuration and growth patternsCitation9,Citation10. Tumors that contain a mixture of both intestinal and diffuse components in similar proportions are called mixed carcinomas. Tumors that show a highly undifferentiated pattern are placed in the indeterminate categoryCitation9.

GC is still a global concern, since it often goes unnoticed, and a high proportion of patients are diagnosed with advanced-stage disease, when prognosis for most of them is poorCitation3,Citation4. The 5-year survival rate in patients with advanced GC is only between 5 and 20%Citation2. Moreover, management of these patients greatly varies among countriesCitation4,Citation11,Citation12. In general, peri- or post-operative chemotherapy has shown improved survival and quality-of-life compared with best supportive care aloneCitation13,Citation14. In first-line regimens, doublet combinations of platinum and fluoropyrimidines are generally usedCitation15–17. However, there is no global consensus across countries regarding the best therapeutic approach, especially in the second-line settingCitation4,Citation11,Citation12. Palliative care is often offered to patients with A/MGC when chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery may not be helpful at that pointCitation3.

There is little information available about the treatment of patients with advanced or metastatic GC (A/MGC) tumors in Colombia. Although there are clinical guidelinesCitation5,Citation6,Citation18, the degree of their implementation is largely unknown. The cost implications of the treatments provided are also unknown. Here, we report patient and disease characteristics, first- and second-line treatment patterns, and associated costs for patients with A/MGC in Colombia, using information collected through a chart review approach from a sample of hospitals in the country.

Methods

Study design

This study is an observational retrospective analysis of treatment patterns and costs for patients with A/MGC in Colombia based on a medical chart review. Information on a cohort of 145 patients was collected from one public hospital (Instituto Nacional de Cancerología E.S.E.) and two private hospitals (Instituto de Cancerología S.A and HematoOncólogos S.A.). Inclusion criteria were: (1) patients with a confirmed diagnosis of A/MGC (including gastroesophageal junction) between January 1, 2009 and June 1, 2016; (2) patients who have completed the first-line treatment with chemotherapy that includes a platinum analog (cisplatin, carboplatin, oxaliplatin) and/or a fluoropyrimidine (5-fluorouracil (5-FU), capecitabine, TS-1) with or without any other medication (biologic or cytotoxic agent), followed by either second-line treatment or palliative therapy; (3) patients aged 18 or older at the time of diagnosis; and (4) availability of medical records including a follow-up of at least 3 months after the last administration of a cytotoxic agent in the first-line treatment (except those recording a documented death) in order to analyze the type of agents used in the second-line treatment. Exclusion criteria were: (1) patients who have participated or were currently participating in any controlled clinical study during the course of the disease; and (2) patients with other malignant disease before or after the diagnosis of A/MGC.

Data collection

De-identified data were collected from patient medical records and analyzed in the selected hospitals after presentation of the protocol and approval from the ethics committee and/or investigation committee. A data collection procedure was developed to retrospectively collect patient level data from the different healthcare institutions. Case report files for each patient were filled in by designated researchers from each center. Quality control monitoring visits were established to assure the validity and reliability of data collection. Patients’ personal data were treated and processed with the appropriate precautions to ensure the confidentiality and compliance with the national laws and regulations. The financial resources to conduct this study were provided by Eli Lilly, and a partnership agreement was signed with each participating institution.

Statistical analysis

The specific objectives of this study were to identify and to describe the patient and disease characteristics as well as the treatment patterns and associated costs in standard clinical practice. Descriptive statistical analysis was conducted for sociodemographic characteristics (e.g. age, sex, etc.), clinical information (e.g. clinical stage, place of original tumor, existence and place of metastases, HER2 status, etc.), and variation in first- and second-line regimens. Patterns for diagnosis and patients’ clinical characteristics were compared with national/institutional guides. Frequency and proportion for categorical variables, and mean and standard deviation for continuous variables are reported. The treatment combinations (regime) for each line and best supportive care are shown. The most frequent combination was defined as the standard treatment. For each regime of the first- and second-line therapy and supportive care method, the specific agents, frequency of administration, and number of patients are described.

We have estimated direct costs for first-line, second-line, and overall. Costs were computed using 2017 unit costs from the Instituto Nacional de Cancerología [National Cancer Institute] (public costs) and costs from the participating private hospitals (private costs). The Appendix includes the unit costs. At the time of cost calculation, one US$ was equivalent to 2.92 COP Colombian pesos (January 31, 2017).

The analysis was performed using SAS (version 9.4) procedures.

Results

Patient, disease, and tumor characteristics

A total of 145 patients were included in this study after applying all inclusion and exclusion criteria (). At diagnosis of A/MGC, the mean patient age was 58.14 (SD = 11.74) years, and 64.83% of patients were male. Slightly more than half (56.1%) of the study population had a history of smoking, and a rather small proportion (18.35%) reported a history of alcohol abuse or dependence. At the index date, the majority of patients (57.38%) were symptomatic, but completely ambulatory (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status [ECOG PS], (1) yet approximately 25% of them were already unable to carry out any work activities (ECOG PS, 2; 23.77%) and capable of only limited self-care (ECOG PS, 3; 1.64%).

Table 1. Patient and disease characteristics.

Upon initial GC diagnosis, a large proportion of patients already had metastatic stage IV disease (79.56%) (). The second most represented stage was stage III (16.06%), predominantly with tumors invading the subserosal, serosal, or adjacent structures and at least one lymph node (10.95%). The most frequent primary tumor location was the antrum, and the pylorus of the stomach (29.41%), followed by the greater and lesser curvature (14.71%), and fundus and corpus (13.24). According to the Laurén classification system, intestinal histology was the most frequently-reported type (59.42%). The method used by the hospitals to test the HER2 status was fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) or/and the immunohistochemistry.

Among the 44 patients tested for HER2 positivity, only nine of them (20.93%) had positive status. About one fourth of the patients (24.62%) carried locally unresectable tumors and, for those that had metastasized, the peritoneum (45.38%) and the liver (30.77%) were the most commonly affected organs ().

Treatment patterns

Patients had received different treatments before the diagnosis with A/MGC (). About one in three patients (41, 28.47%) of the study population had undergone surgery, of which about one third (13, 31.71%) suffered total gastrectomy. Less commonly, patients had followed chemotherapy (10.42%), radiotherapy (6.21%), or adjuvant chemoradiotherapy with 5-FU (4.26%) or another drug (1.42%).

Table 2. Therapies prior to A/MGC diagnosis and number of patients per line of treatment.

Upon A/MGC diagnosis, and according to the inclusion criteria, all patients initiated first-line therapy with a platinum analog and/or a fluoropyrimidine. Less than half of them (41.38%) followed a second-line of treatment, and much less of them underwent a third- (9.66%) or fourth-line (2.76%) (). presents all first- and second-line treatment combinations followed by the 145 and 60 patients, respectively. shows the first and second line treatments with a specified number/percentage for each drug, separately.

Figure 1. Most common treatment regimens in (A) first- (n = 145) and (B) second-line (n = 60). #Other: capecitabine (6%), epirubicin + cisplatin + 5-FU (6%), carboplatin + 5-FU (6%), leucovorin + oxaliplatin + 5-FU (3%), carboplatin + capecitabine (3%), docetaxel + cisplatin + 5-FU (2%), epirubicin + cisplatin + capecitabine (2%), docetaxel + cisplatin (1%), paclitaxel + carboplatin (1%), trastuzumab + cisplatin + 5-FU (1%), docetaxel + carboplatin + 5-FU (1%), 5-FU (1%), trastuzumab + oxaliplatin + capecitabine (1%), docetaxel + pegfilgastrin + cisplatin (1%), docetaxel + cisplatin + 5-FU + capecitabine (1%), doxorubicin + cisplatin + capecitabine (1%), leucovorin + etoposide + 5-FU (1%), docetaxel + pegfilgastrin + leucovorin + oxaliplatin + 5-FU (1%). ##Other:irinotecan + cisplatin (5%), irinotecan + leucovorin + 5-FU (3%), cisplatin + capecitabine (2%), epirubicin + oxaliplatin + capecitabine (2%), carboplatin + 5-FU (2%), leucovorin + oxaliplatin + 5-FU (2%), paclitaxel + carboplatin (2%), paclitaxel + cisplatin (2%), trastuzumab + capecitabine (2%), carboplatin + capecitabine (2%), cisplatin (2%), trastuzumab + leucovorin + irinotecan +c 5-FU (2%), oxaliplatin + 5-FU (2%), trastuzumab + carboplatin + 5-FU (2%), palliative therapy (2%). Abbreviation. 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil.

Table 3. Drug treatments per line.

First-line treatment

At the start of the therapy, more than half of the patients (59.17%) had an ECOG PS rating of 1, one quarter of them had a rating of 2, and a few of them (15%) had a perfect performance status (ECOG PS, 0). There were virtually no patients (0.83%) with an ECOG PS of 3 ().

Table 4. Patient characteristics prior to initiation of first- and second-lines treatments, and best response to treatment.

Of the 145 patients enrolled in this retrospective study, 97 of them (66.9%) received a two-drug combination, 36 of them (24.8%) a three-drug combination, and 10 of them (6.9%) a single drug treatment (monotherapy). 5-FU in combination with cisplatin was the most frequent treatment (14%), followed by 5-FU + leucovorin (12%), capecitabine + cisplatin (10%), capecitabine + oxaliplatin (10%), paclitaxel + cisplatin doublet (9%), and epirubicin + oxaliplatin + capecitabine triplet (8%). Other mono, double and triple therapies are described in . Approximately 10% (10.31%) of the patients responded to treatment, either completely (0.79%) or partially (9.52%). The majority of them presented progressive (53.97%) and stable (17.46%) disease.

Second-line treatment

In the second-line setting, a higher percentage of patients (72.34%) had an ECOG PS rating of 1 prior to therapy initiation (). Second-line initiators mostly received monotherapy (45%) with paclitaxel (18.33%), capecitabine (16.67%), 5-FU (15%), and irinotecan (8.33%) (). Overall, treatment regimens based on a platinum analog and/or a fluoropyrimidine were still administered to 43 of them (71.67%). Among the patients that received second-line chemotherapy, there were no total responders. Of these patients, over half (52%) progressed, 20% stabilized, and 8% partially responded ().

Supportive care and treatment-related costs

After the diagnosis of A/MGC, best supportive care most frequently consisted in outpatient visits after last line-therapy (72.41%) (). Overall, 18.6% of the patients received palliative radiotherapy, and a high percentage of them (37.24%) also underwent surgery ().

Table 5. Supportive care received.

shows the mean and the median of patient treatment costs, either for the first-, second-, or for all therapy lines using the prices indicated in the public system, and presents the costs using the unit costs from the private system. There was a high difference in the estimated costs. The mean cost per patient using the public system costs for all lines was COL $5,487,409 (Colombian Pesos) (US$1,879,249) (SD = COL $3,861,700, US$132,250), of which COL $1,229,037 (US$42,090) and COL $1,589,710 (US$544,421) were invested in radiology and nuclear medicine and in overall procedures, respectively (). The mean cost per patient using the private system costs for all lines was COL $25,545,372 (US$874,841) (SD = COL $21,849,591, US$748,227) (). Most of these costs were in radiology and nuclear medicine (COL $16,105,116, US$551,545).

Table 6. Treatment costs (using public unit costs).

Table 7. Treatment costs (using private unit costs).

Discussion

Discrepancies among GC clinical guidelines and limited availability of clinical trial data

Early GC have a good prognosis after surgery (about 90% of patients survive 10 years)Citation8. Endoscopic limited resection is only appropriate for select, very early tumorsCitation15,Citation16. Nevertheless, almost all patients of our cohort had already been diagnosed with advanced stage disease at first diagnosis of GC. On a worldwide scale, the 5-year survival rate of advanced GC is only 5–20%Citation2. Globally, limited clinical data are available for the most appropriate management of advanced-stage patients. A recent work by Bauer et al.Citation12 pooled the results of a literature search of six different guidelines published after 2010 and across countries, including the EU, USA, Japan, UK, and Canada. The authors found that the results of identical studies on the management of advanced GC had been interpreted differently in different countries, leading to discrepancies in international guideline recommendationsCitation12. The most important studies on which these guidelines are based included four to 11 clinical trials, case-control studies, and cohort studies like the MAGIC, ACCORD, CLASSIC, and ACTS-GC3, which investigated the benefits of perioperative and adjuvant chemotherapy and radiochemotherapyCitation12.

For stage IB–III gastric cancer, radical gastrectomy accompanied by lymphadenectomy is indicatedCitation15–17. Perioperative (pre- and post-operative) chemotherapy with a platinum/fluoropyrimidine combination is recommended by the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) clinical guidelines for these patients undergoing surgeryCitation16. In the US, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) considers surgery as the selected choice, followed by adjuvant chemoradiotherapyCitation15. In Japan, post-operative adjuvant chemotherapy is recommendedCitation17. The extent of nodal dissection accompanying radical gastrectomy has been extensively debated tooCitation16. In Asian countries, observational and randomized trials could show that D2 resection (removal of perigastric lymph nodes plus those along the left gastric, common hepatic and splenic arteries, and the celiac axis) implies higher outcomes compared with D1 resection (removal of the perigastric lymph nodes)Citation17. However, consensus in Western countries is that only medically fit patients should undergo D2 dissection, as trials have failed to prove any survival advantage of the latter typeCitation16. In conclusion, the therapeutic intervention of choice for advanced GC notably differs across countries. Thus, considerable effort is required to improve comparability of the existing guidelines and to create an international consensusCitation12.

Heterogeneity of treatment regimens

In the advanced/metastatic gastric cancer scenario, therapeutic options are reduced. The majority of patients eligible for our study fell into this category at first diagnosis of GC. Lymphatic and vascular invasion and metastasis lead to poor prognosis, as the efficacy of surgery and current therapies is seriously compromisedCitation11. Worldwide, approximately one million GC new cases are diagnosed every year, with 800,000 GC-related deathsCitation11. Except for Korea and Japan, where extensive screening programs are run, about two thirds of GC patients are already diagnosed at an advanced stageCitation11. In Colombia, where GC is usually unresectable when it is clinically discoveredCitation5, mortality figures are similar to incidence (17.4–48.2 per every 100,000 inhabitants)Citation6.

It has been demonstrated that chemotherapy is more effective in terms of survival and quality-of-life than best supportive care alone for patients with advanced/metastatic tumorsCitation19–21. The ESMO guidelines do not recommend resecting the primary tumor. However, this procedure may be reconsidered if there is a good response to chemotherapyCitation16. Platinum-based agents in combination with fluoropyrimidines are the gold standard of systemic treatment in the first-line settingCitation13,Citation15,Citation16. Globally, although 5-FU is still the most frequently administered fluoropyrimidineCitation13, oral capecitabine and S-1 were at least equivalent to intravenous 5-FU in terms of overall survivalCitation13,Citation22,Citation23. In our study, although 5-FU in combination with cisplatin was the standard first-line treatment, we observed a remarkable variability in treatment choices, both in doublet and triplet regimens, and in combination with taxanes and/or anthracyclins.

The use of triplets is controversial, and they are not generally accepted as standards of careCitation13,Citation16. A meta-analysis has shown significant benefit from the addition of an anthracycline to a platinum/fluoropyrimidine first-line doubletCitation24. However, this combination may have serious tolerability problems. Among triplets containing an anthracycline, EOX (epirubicin, oxaliplatin, capecitabine) was associated with a longer median overall survival (OS) than ECF (epirubicin, cisplatin, 5-FU)Citation25. In our study cohort, 15% of patients in the first-line setting received an epirubicin-containing triplet, either in combination with oxaliplatin or cisplatin. Several trials have demonstrated a non-inferiority of oxaliplatin vs cisplatin in combination with epirubicin and a fluoropyrimidineCitation26–28. Therefore, oxaliplatin may be considered as an appropriate cisplatin replacement, reducing the cisplatin-associated toxicities. However, oxaliplatin is also associated with significant neuropathy.

Irinotecan constitutes another alternative to platinum derivates. In combination with 5-FU, irinotecan did not show an improved time-to-progression compared to cisplatin + 5-FU, but had a better tolerability profileCitation29,Citation30. Also, there are randomized phase II and III trials on the use of FOLFIRI triplet (irinotecan plus leucovorin and 5-FU) in GCCitation29,Citation31and guidelines suggest its use for either selected patientsCitation16 or second-line therapiesCitation15. In spite of this evidence, no patients in our cohort received irinotecan in the first-line of treatment.

In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, Shi et al.Citation32 showed that first-line therapies for metastatic gastric cancer that include a taxane may be good candidates for the combined treatment. Several GC guidelines also recommend the use of taxanesCitation15–17. However, several modified DCF (docetaxel, cisplatin, 5-FU) regimens have been developed in order to minimize taxane-related adverse events, especially in the elderly populationCitation13. The majority of taxane-containing first-line therapies of our study are doublets with either cisplatin or oxaliplatin, and not triplets.

In patients with appropriate PS (0–2), second-line treatment improved OS and quality-of-life compared with best supportive careCitation33–36. Based on the development of recent medications, guidelines have included ramucirumab, as a single agent or in combination with paclitaxel as options for second-line therapy. Irinotecan, paclitaxel, and docetaxel are also included as monotherapy for second-line therapy if not used beforeCitation13,Citation15,Citation16. Our results are partially in line with these recommendations, as 18% and 8% of patients under second-line chemotherapy received paclitaxel and irinotecan as single drugs, respectively. Nevertheless, we observed that the rest of the regimens administered in the second-line setting were highly heterogeneous too, as doublets and triplets with platinum-based drugs and fluoropyrimidines were also used. It remains unclear if a proportion of patients were re-challenged with the same first-line regimens after the follow-up periodCitation16. Finally, only around 10% of them continued with a third- or fourth-line of treatment. In fact, there is no evidence supporting any benefit beyond the second lineCitation16.

Targeted therapies may drive us to a real improvement of the treatment of A/MGCpatientsCitation13,Citation15,Citation16. So far, trastuzumab and ramucirumab (targeting HER2 and VEGFR2, respectively) are the only targeted therapies that have succeeded in clinical trialsCitation37. In fact, the last update of the NCCN guidelines includes the use of single-agent ramucirumab, or the combination with paclitaxel, for second-line therapy after recurrence or progression of GCCitation15. Administration of trastuzumab is also recommended in different guidelines for HER2-positive GC patientsCitation15,Citation16, but only in first-line treatment. Of note, our data show that only three patients received trastuzumab in the first scheme, even though nine of the 44 patients tested for the HER2 showed positive expression.

Poor response to treatment

Currently, second-line treatment is administered to up to 50% and 80% of GC patients in European and in Asian clinical trials, respectivelyCitation13. In our study, only ∼1% of first-line initiators showed complete response and ∼10% partially responded during the 3-months follow-up period. This may explain the high percentage (∼40%) of patients initiating a second-line of treatment.

It is estimated that the median survival rate of patients with advanced GC is still less than 12 months, and the clinical response rate for advanced or metastatic GC ranges between 28% and 54%Citation27,Citation38–42. In some cases, novel combined chemotherapy treatments have a good response for A/MGC gastric cancer and allow the undertaking of potentially curative gastrectomyCitation43–45. Nevertheless, a pathological complete response is a rare event, even under these regimensCitation43–45. In our report, the percentage of patients with disease progression still remained at ∼50%, and no complete response or little partial response were observed.

The findings from this report and others suggest that treatment of advanced GC, especially A/MGC, is still a major challenge. Recommendations of clinical management and therapeutic intervention among different clinical guidelines are not comparable, although they are based on the same and limited number of trials. Only modest clinical improvements have been achieved in the last years by integrating second-line regimens and targeted therapies in the routine. However, overall current therapies have limited curative efficacy and, therefore, new treatment strategies are urgently needed.

In Colombia, there are a limited number of studies describing the management of patients with A/MGCCitation5,Citation6,Citation18. Besides, none of them has systematically described the treatment received by patients in a sample of hospitals in the country. Here, we shed light on the current care and treatment for A/MGC in this country. Future research could build on this initial work to improve individual and institutional decisions about the therapies provided to these patients to ameliorate their clinical outcome. On the other hand, it would also contribute to better identifying associated costs that would eventually impact on the country’s health system.

The findings of this study need to be interpreted with the understanding that it is based on a retrospective collection of data from clinical charts. As such, some information may be missing or incomplete.

Conclusions

Our observational study was designed to determine patient and disease characteristics, and treatment patterns of Colombian patients with A/MGC. Overall, we observed highly heterogeneous treatment patterns for these patients. 5-FU in combination with cisplatin was the standard first-line treatment for A/MGC. Patients who initiated second-line therapy (less than 50% of our cohort) mostly received monotherapy with paclitaxel, capecitabine, irinotecan, or cisplatin, although regimens based on a platinum analog and/or a fluoropyrimidine were still administered to a considerable number of patients. The observed response rate to treatment was poor, with most of the patients having documented responses of progressive disease or stable disease after both regimens. Around 10% of patients responded to first-line chemotherapy, and 8% responded only partially to the second-line one. Treatment patterns were highly heterogenous and costs of treatment were high. There is a need for further studies on the treatment patterns of patients with gastric cancer in Colombia, given the heterogeneity of treatments provided.

Transparency

Declaration of financial/other relationships

DN, FL, and EDLKP are Eli Lilly employees. JMH has received honoraria for participating in Eli Lilly and Co., Roche, Otsuka, and Lundbeck advisory boards or educational presentations. The authors and JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial or other relationships apart from those disclosed.

Acknowledgements

None reported.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–E386.

- Piazuelo MB, Correa P. Gastric cancer: overview. Colomb Med. 2013;44:192–201.

- Torpy JM, Lynm C, Glass RM. JAMA patient page. Stomach cancer. JAMA. 2010;303:1771.

- Bang YJ, Yalcin S, Roth A, et al. Registry of gastric cancer treatment evaluation (REGATE): I baseline disease characteristics. Asia-Pac J Clin Oncol. 2014;10:38–52.

- Daza DE. Cáncer Gástrico en Colombia entre 2000 y 2009 [Gastric Cancer in Colombia between 2000 and 2009]. 2012. Spanish.

- Restrepo AF, Riveros JH. Guías de Práctica Clínica-GPC Para el Cancer Gastrico [Practice guidelines for Gastric Cancer]. 2014. Spanish.

- Torres J, Correa P, Ferreccio C, et al. Gastric cancer incidence and mortality is associated with altitude in the mountainous regions of Pacific Latin America. Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24:249–256.

- Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, et al. WHO Classification of tumours of the digestive system. 4th ed. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2010.

- Lauren T. The two histologic main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. An attempt at a histo-clinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31–49.

- Hu B, El Hajj N, Sittler S, et al. Gastric cancer: classification, histology and application of molecular pathology. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2012;3:251–261.

- Kim R, Tan A, Choi M, et al. Geographic differences in approach to advanced gastric cancer: is there a standard approach? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;88:416–426.

- Bauer K, Schroeder M, Porzsolt F, et al. Comparison of international guidelines on the accompanying therapy for advanced gastric cancer: reasons for the differences. J Gastric Cancer. 2015;15:10–18.

- Digklia A, Wagner AD. Advanced gastric cancer: current treatment landscape and future perspectives. WJG. 2016;22:2403–2414.

- Janowitz T, Thuss-Patience P, Marshall A, et al. Chemotherapy vs supportive care alone for relapsed gastric, gastroesophageal junction, and oesophageal adenocarcinoma: a meta-analysis of patient-level data. Br J Cancer. 2016;114:381–387.

- The National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) for Gastric Cancer (version 2). 2016. [cited 2018 Dec 9]. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/gastric.pdf

- Smyth EC, Verheij M, Allum W, et al. Gastric cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:v38–v49.

- Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese Gastric Cancer treatment guidelines 2014 (version 4). Gastric Cancer. 2017;20(1):1–19. doi:10.1007/s10120-016-0622-4.

- López-Moncayo H, Ospina-Nieto J, Rubiano-Vinueza J, et al. Cáncer Gástrico [Gastric Cancer]. Guías de Manejo en Cirugía [Surgical Management Guidelines]. Bogotá, Colombia: Asociación Colombiana de Cirugía; 2009. Spanish.

- Wagner AD, Grothe W, Haerting J, et al. Chemotherapy in advanced gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis based on aggregate data. JCO. 2006;24:2903–2909.

- Glimelius B, Ekstrom K, Hoffman K, et al. Randomized comparison between chemotherapy plus best supportive care with best supportive care in advanced gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 1997;8:163–168.

- Bouche O, Raoul JL, Bonnetain F, et al. Randomized multicenter phase II trial of a biweekly regimen of fluorouracil and leucovorin (LV5FU2), LV5FU2 plus cisplatin, or LV5FU2 plus irinotecan in patients with previously untreated metastatic gastric cancer: a Federation Francophone de Cancerologie Digestive Group Study–FFCD 9803. JCO. 2004;22:4319–4328.

- Cassidy J, Saltz L, Twelves C, et al. Efficacy of capecitabine versus 5-fluorouracil in colorectal and gastric cancers: a meta-analysis of individual data from 6171 patients. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:2604–2609.

- Aguado C, Garcia-Paredes B, Sotelo MJ, et al. Should capecitabine replace 5-fluorouracil in the first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer? WJG. 2014;20:6092–6101.

- Okines AF, Norman AR, McCloud P, et al. Meta-analysis of the REAL-2 and ML17032 trials: evaluating capecitabine-based combination chemotherapy and infused 5-fluorouracil-based combination chemotherapy for the treatment of advanced oesophago-gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1529–1534.

- Starling N, Rao S, Cunningham D, et al. Thromboembolism in patients with advanced gastroesophageal cancer treated with anthracycline, platinum, and fluoropyrimidine combination chemotherapy: a report from the UK National Cancer Research Institute Upper Gastrointestinal Clinical Studies Group. JCO. 2009;27:3786–3793.

- Yamada Y, Higuchi K, Nishikawa K, et al. Phase III study comparing oxaliplatin plus S-1 with cisplatin plus S-1 in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:141–148.

- Al-Batran SE, Hartmann JT, Probst S, et al. Phase III trial in metastatic gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma with fluorouracil, leucovorin plus either oxaliplatin or cisplatin: a study of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1435–1442.

- Cunningham D, Starling N, Rao S, et al. Capecitabine and oxaliplatin for advanced esophagogastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:36–46.

- Dank M, Zaluski J, Barone C, et al. Randomized phase III study comparing irinotecan combined with 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid to cisplatin combined with 5-fluorouracil in chemotherapy naive patients with advanced adenocarcinoma of the stomach or esophagogastric junction. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1450–1457.

- Moehler M, Kanzler S, Geissler M, et al. A randomized multicenter phase II study comparing capecitabine with irinotecan or cisplatin in metastatic adenocarcinoma of the stomach or esophagogastric junction. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:71–77.

- Guimbaud R, Louvet C, Ries P, et al. Prospective, randomized, multicenter, phase III study of fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan versus epirubicin, cisplatin, and capecitabine in advanced gastric adenocarcinoma: a French intergroup (Federation Francophone de Cancerologie Digestive, Federation Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer, and Groupe Cooperateur Multidisciplinaire en Oncologie) study. JCO. 2014;32:3520–3526.

- Shi J, Gao P, Song Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of taxane-based systemic chemotherapy of advanced gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:5319.

- Thuss-Patience PC, Kretzschmar A, Bichev D, et al. Survival advantage for irinotecan versus best supportive care as second-line chemotherapy in gastric cancer–a randomised phase III study of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie (AIO). Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:2306–2314.

- Ford HE, Marshall A, Bridgewater JA, et al. Docetaxel versus active symptom control for refractory oesophagogastric adenocarcinoma (COUGAR-02): an open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:78–86.

- Kang JH, Lee SI, Lim DH, et al. Salvage chemotherapy for pretreated gastric cancer: a randomized phase III trial comparing chemotherapy plus best supportive care with best supportive care alone. JCO. 2012;30:1513–1518.

- Roy AC, Park SR, Cunningham D, et al. A randomized phase II study of PEP02 (MM-398), irinotecan or docetaxel as a second-line therapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1567–1573.

- Apicella M, Corso S, Giordano S. Targeted therapies for gastric cancer: failures and hopes from clinical trials. Oncotarget. 2017;8:57654–57669.

- Koizumi W, Narahara H, Hara T, et al. S-1 plus cisplatin versus S-1 alone for first-line treatment of advanced gastric cancer (SPIRITS trial): a phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:215–221.

- Van Cutsem E, Moiseyenko VM, Tjulandin S, et al. Phase III study of docetaxel and cisplatin plus fluorouracil compared with cisplatin and fluorouracil as first-line therapy for advanced gastric cancer: a report of the V325 Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4991–4997.

- Ohtsu A, Shimada Y, Shirao K, et al. Randomized phase III trial of fluorouracil alone versus fluorouracil plus cisplatin versus uracil and tegafur plus mitomycin in patients with unresectable, advanced gastric cancer: The Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study (JCOG9205). JCO. 2003;21:54–59.

- Boku N, Yamamoto S, Fukuda H, et al. Fluorouracil versus combination of irinotecan plus cisplatin versus S-1 in metastatic gastric cancer: a randomised phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:1063–1069.

- Yamaguchi K, Shimamura T, Hyodo I, et al. Phase I/II study of docetaxel and S-1 in patients with advanced gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:1803–1808.

- Wang Y, Yu YY, Li W, et al. A phase II trial of Xeloda and oxaliplatin (XELOX) neo-adjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery for advanced gastric cancer patients with para-aortic lymph node metastasis. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;73:1155–1161.

- Okabe H, Ueda S, Obama K, et al. Induction chemotherapy with S-1 plus cisplatin followed by surgery for treatment of gastric cancer with peritoneal dissemination. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:3227–3236.

- Suzuki T, Tanabe K, Taomoto J, et al. Preliminary trial of adjuvant surgery for advanced gastric cancer. Oncol Lett. 2010;1:743–747.

- Instituto Nacional de Cancerología [National Cancer Institute]. Bogotá, Colombia. [cited 2018 Jul 20]. Available from: http://www.cancer.gov.co/. Spanish

- Instituto de Cancerología S.A. [Cancer Institute]. Medellín, Colombia. [cited 2018 Jul 20]. Available from: https://institutodecancerologia.lasamericas.com.co/. Spanish.