Abstract

Objective: To describe the prevalence and costs of anxiety and depression among moderate-to-severe psoriasis (PsO) patients in a commercially-insured US population.

Methods: The IBM MarketScan Commercial database was used to select adults with moderate-to-severe PsO (≥1 PsO diagnosis and ≥1 systemic or biologic medication) within each calendar year from 2014 to 2016. Adults with no diagnosis of PsO or similar disorders were randomly selected (2014–2016) and matched 1:1 to PsO patients to compare the prevalence of anxiety and depression each year. Moderate-to-severe PsO patients identified in 2014 with continuous enrollment through 2015 were stratified into those with treated anxiety and/or depression (≥1 anxiety or depression diagnosis plus any anxiolytics, antidepressants, or antipsychotics within 30 days) vs those without anxiety/depression, and then matched 1:1 to determine the incremental burden of treated anxiety/depression among PsO patients. All-cause and PsO-related healthcare costs were compared between the matched cohorts using generalized linear models.

Results: In total, 69,644 matched PsO and non-PsO patients were identified in 2014, 61,478 in 2015, and 66,880 in 2016. The prevalence of anxiety/depression among PsO patients increased more than for matched controls, from 18.2% vs 12.2% in 2014 (p < 0.01) to 19.6% vs 13.1% in 2016 (p < 0.01). Prevalence of treated anxiety/depression followed the same trend, with increases from 14.5% vs 8.9% in 2014 (p < 0.01) to 15.9% vs 9.9% in 2016 (p < 0.01). For patients with moderate-to-severe PsO, unadjusted incremental all-cause healthcare costs associated with treated anxiety/depression were $8,077 (p < 0.01); 91% was due to utilization of medical services such as hospitalizations, ER visits, office visits, and other outpatient services (all p < 0.01).

Conclusions: The prevalence of psychiatric disorders is higher among PsO patients than the general population, and the incremental burden of treated anxiety/depression is substantial. Further research is needed, but PsO treatments that improve psychiatric symptoms such as anxiety/depression may benefit patients and reduce their economic burden.

Introduction

Psoriasis (PsO) is a chronic, immune-mediated inflammatory disease characterized by skin lesions accompanied by pain, itching, burning, and scaling. With an overall prevalence of ∼3% in the US adult population, PsO affected an estimated 7.4 million adults in 2013Citation1. The economic burden of psoriasis is substantial. A systematic review estimated the total annual cost of PsO in the US to be $112 billion in 2013 dollars, with direct costs ranging from $51.7 billion to $63.2 billionCitation2. When stratified by disease severity, moderate-to-severe PsO patients had nearly 3-fold higher outpatient costs, 10-fold higher pharmacy costs, and over 2-fold higher inpatient and emergency room (ER) visit costs compared to patients with mild PsOCitation3.

The psychosocial burden of PsO is also significant. The changes in physical appearance caused by PsO often lead to social stigmatization and psychological distress, which can increase the risk of psychiatric comorbidities, such as depression and anxiety. Systematic reviews have reported the prevalence of depression or depressive symptoms among PsO patients ranging from 4–68% based on various outcome definitions, study designs, and study populationsCitation4–6. The estimated prevalence of anxiety or anxiety symptoms varies as wellCitation4,Citation6,Citation7. Greater disease severity also correlates with an increased risk of depressionCitation8,Citation9 and patients who experience treatment failure have a higher occurrence of both depression and anxietyCitation10. Furthermore, both anxiety and depression are associated with the upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines and other inflammatory pathway components which may trigger PsO or exacerbate disease severity, resulting in even greater disease burdenCitation11,Citation12.

Han et al.Citation13 found that healthcare costs among patients with moderate-to-severe PsO increased from $10,363 without a comorbid psychiatric disorder to $17,638 with the presence of a psychiatric disorder. This increase was the result of more than 3-fold higher inpatient and ER visit costs, 1.8-fold higher outpatient costs, and 1.2-fold higher prescription costs among PsO patients with psychiatric disorders compared to PsO patients without psychiatric disorders. In addition, PsO patients with comorbid anxiety or depression reported significantly worse QoL and higher overall work impairment in comparison to PsO patients without anxiety or depressionCitation14. Limited data are available on contemporary prevalence rates and economic burden of psychiatric comorbidities among moderate-to-severe PsO patients in the real-world setting. This study aimed to describe anxiety and depression prevalence trends as well as the incremental direct costs associated with treated anxiety/depression among patients with moderate-to-severe PsO in a commercially-insured US population from 2014 to 2016. In addition, analyses were performed to evaluate indirect costs (due to absenteeism or short-term disability) among a sub-group of PsO patients with vs without treated anxiety/depression.

Methods

Data sources

Data were extracted from the IBM MarketScan Commercial Claims (Commercial) database and the Health and Productivity Management (HPM) database from 1 January 2014 to 31 December 2016. The Commercial database is a fully adjudicated medical and pharmacy insurance claims database that contains pharmacy prescription drug and medical (inpatient admission and outpatient service) claims of ∼138 million unique de-identified employees and their dependents since 1995. It provides detailed healthcare outcome measures including resource utilization and associated costs for individuals covered annually by a geographically diverse group of self-insured employers and private insurance plans across the US. The HPM database contains workplace, short-term, and long-term disability data, and information about workers’ compensation for a sub-set of enrollees in the Commercial database. Absenteeism is derived from individual employee time reporting records collected through employers. Short-term and long-term disability data consist of case records that include case dates, payment, and clinical information, collected by employers who offer disability benefits to their employees. Case-level worker’s compensation information includes date(s) that an employee was absent from work, payments, and information describing the nature of the worker’s compensation case. Approximately 70 employers contribute data to the HPM database. The HPM data are linkable to the corresponding medical and pharmacy claims data for employees in the Commercial database. Data in both the Commercial and HPM databases are de-identified and compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations.

Study patients

Prevalence of anxiety/depression

For analysis of the prevalence of anxiety and depression, adults with moderate-to-severe PsO in 2014, 2015, and 2016 were matched to adults with no diagnoses for PsO during the same time period. Adult moderate-to-severe PsO patients were identified based on the presence of ≥1 PsO diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [ICD-9]: 696.1, 696.8; Tenth Revision [ICD-10]: L40.0, L40.8, and L40.9) in combination with ≥1 prescribed systemic or biologic PsO medication (Supplementary Appendix 1) within the individual calendar years of 2014, 2015, or 2016. PsO patients were required to be ≥18 years of age at the beginning of each respective year (cases, PsO cohort). Adults with no diagnosis of PsO or disorders similar to PsO (ICD-9: 696; ICD-10: L40) from 2014 to 2016 (controls, Non-PsO cohort) were randomly selected and matched to patients with moderate-to-severe PsO in a 1:1 ratio on age (birth year and month), gender, health plan type, and region using the exact attribute matching method to ensure comparability and reduce potential confounding caused by demographic characteristics. All patients were required to have continuous enrollment in the corresponding calendar year. The study definition of anxiety and depression is provided in the following section.

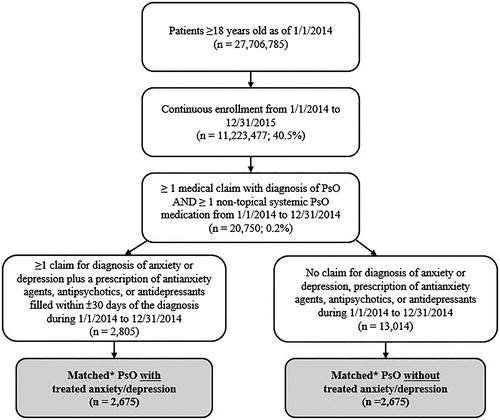

Burden of treated anxiety/depression among PsO patients

For analysis of the incremental costs associated with treated anxiety/depression, adults with moderate-to-severe PsO in 2014 (patient identification period) were stratified into two cohorts consisting of patients with treated anxiety and/or depression and those without any evidence of anxiety or depression. Adult moderate-to-severe PsO patients were identified based on the presence of ≥1 diagnosis of PsO in combination with ≥1 prescribed systemic or biologic PsO medication within 2014 and were required to be ≥18 years of age as of 1 January 2014 and have continuous health plan enrollment from January 1, 2014 to December 31, 2015. Patients with treated anxiety and/or depression were further required to have ≥1 diagnosis of anxiety (ICD-9: 300.0; ICD-10: F41) and/or depression (ICD-9: 296.2, 296.3, 300.4, 311; ICD-10: F32, F33, F34.1) in combination with a prescription for antianxiety, antipsychotic, or antidepressant agents (Supplementary Appendix 2) filled within ±30 days of a diagnosis code (cases, PsO with Treated Anxiety/Depression cohort). Moderate-to-severe PsO patients with no diagnoses of anxiety or depression as well as no prescription claims for anti-anxiety, antipsychotic, or antidepressant agents (controls, PsO without Anxiety/Depression cohort) were randomly selected and matched with cases in a 1:1 ratio based on age, gender, health plan type, and region using the exact attribute matching method displays patient attrition of the study population.

Study measures

Prevalence of anxiety/depression

The number of matched moderate-to-severe PsO patients and non-PsO control patients who had the following psychiatric comorbidities in 2014, 2015, and 2016, respectively, was described: any anxiety/depression, treated anxiety/depression, treated major depressive disorder (MDD), and untreated anxiety/depression. Any anxiety/depression was defined as the presence of ≥1 diagnosis of anxiety and/or depression in each calendar year. Treated anxiety/depression was defined as the presence of ≥1 diagnosis of anxiety and/or depression accompanied by ≥1 prescription claim for any anxiolytic, antipsychotic, or antidepressant filled within ±30 days of a diagnosis code for anxiety/depression. Treated MDD was defined as the presence of ≥1 diagnosis of MDD (ICD-9: 296.2, 296.3; ICD-10: F32, F33) accompanied by ≥1 prescription claim for an antidepressant filled within ±30 days of a diagnosis code for MDD. Untreated anxiety/depression was defined as the presence of ≥1 diagnosis of anxiety and/or depression with no evidence of a prescription for any anxiolytic, antipsychotic, or antidepressant pharmacotherapy during the identification period. The prevalence was calculated by dividing the number of comorbid patients with the total cohort population of interest.

Burden of treated anxiety/depression among PsO patients

In order to determine the incremental burden associated with treated anxiety/depression among PsO patients, all-cause and PsO-related healthcare costs in 2015 were evaluated for the matched moderate-to-severe PsO cohort with treated anxiety and/or depression vs the cohort without any anxiety or depression. All-cause healthcare costs were defined as the sum of plan-paid and patient-paid costs associated with any conditions incurred from inpatient admissions, ER visits, outpatient services, and outpatient pharmacy prescriptions. PsO-related medical costs included those associated with a PsO diagnosis and costs for PsO-related biologics and other systemic medications incurred from either medical claims or pharmacy claims. All-cause and PsO-related healthcare costs in 2015 were compared between the cohort with treated anxiety/depression vs the cohort without anxiety or depression. Patients in the treated anxiety/depression cohort were further stratified into those with both anxiety and depression, anxiety only, or depression only, and costs for each group were also assessed.

Among a sub-group of patients who could be linked with the HPM database, lost time due to absenteeism or short-term disability was reported. Indirect costs associated with absenteeism were calculated by multiplying the number of hours absent in 2015 with an average hourly wage. Wages were based on the 2015 age–gender adjusted wage rate from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS)Citation15. Since employers typically pay 70% of wages as part of a short-term disability (STD) benefitCitation16, indirect costs associated with STD were estimated by multiplying the number of lost days by 70% of the 2015 BLS age-gender stratified daily wage rate.

Patient demographics such as age, gender, geographic region (US census division), and type of insurance at the time of patient identification were determined. The Quan-Charlson Comorbidity Index (QCI) was used to measure general comorbid conditions during the identification period. The proportion of patients with the following comorbid conditions during the identification period was also determined: other psychiatric conditions (bipolar/manic depression, dementia, schizophrenic/delusional disorders, substance use disorders, suicidal ideation), other immunological conditions (psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, juvenile chronic polyarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, hidradenitis suppurativa, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis), diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, liver cirrhosis, obesity, thyroid disease, and uveitis (Supplementary Appendix 3). Concomitant use of the following drug classes during the follow-up period were determined: anticholinergic agents, respiratory medications, and opioids/narcotics (Supplementary Appendix 4).

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for study measures and outcomes. Mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for all continuous variables; frequencies and percentages were reported for categorical variables. Statistical significance of differences in terms of baseline characteristics between the matched moderate-to-severe PsO cohort with treated anxiety and/or depression and the cohort without any anxiety or depression was assessed using the t-test for continuous variables and Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Generalized linear models with gamma distribution and logarithm link function were used to estimate the incremental costs attributable to treated anxiety/depression after adjusting for patient demographic characteristics and comorbid conditions. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS Enterprise Guide 7 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Among adult members with continuous enrollment in 2014, 2015, or 2016, the percentage of PsO patients was 0.8% for each of the 3 years. Among eligible patients with PsO, the percentage with moderate-to-severe PsO (≥1 systemic PsO medication) was 23.4%, 25.8%, and 27.4% in 2014, 2015, and 2016, respectively. A total of 34,822 patients were included in each of the matched moderate-to-severe PsO and non-PsO cohorts in 2014, while 30,739 patients were included in each cohort in 2015, and 33,440 patients were included in each cohort in 2016. The mean age of patients was 48 years and was similar across cohorts. Based on measurement of the Quan-Charlson Comorbidity index, patients with moderate-to-severe PsO had significantly higher overall burden of disease than controls for each year (all p < 0.01).

Prevalence of anxiety/depression

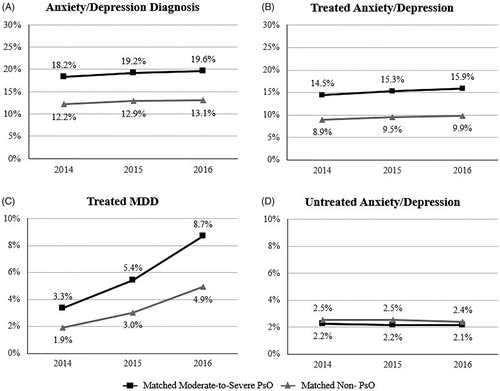

The prevalence of patients with an anxiety and/or depression diagnosis among moderate-to-severe PsO patients increased from 18.2% in 2014 to 19.6% in 2016, as compared with an increase from 12.2% (p < 0.01) in 2014 to 13.1% (p < 0.01) in 2016 for matched controls ().

Prevalence of treated anxiety/depression

The prevalence of treated anxiety and/or depression among moderate-to-severe PsO patients increased from 14.5% in 2014 to 15.9% in 2016, as compared with an increase from 8.9% (p < 0.01) in 2014 to 9.9% (p < 0.01) in 2016 for matched controls (). The prevalence of treated MDD among moderate-to-severe PsO patients was higher than that for their matched non-PsO counterparts; increasing from 3.3% vs 1.9% in 2014 (p < 0.01) to 8.7% vs 4.9% in 2016, respectively (p < 0.01) (). The percentage of patients with untreated anxiety and/or depression was ∼2–3% for PsO and non-PsO patients across the 3-year study period ().

Characteristics of study patients

A total of 5,350 moderate-to-severe PsO patients were matched based on whether or not they had treated anxiety/depression (n = 2,675 in each case and control cohort). These study patients had a mean (± SD) age of 49 (± 10) years, and 66% were female (). In comparison to their matched controls, PsO patients with treated anxiety/depression had a significantly higher overall burden of comorbidity, as measured by the Quan-Charlson Comorbidity Index score (QCI score of 0.7 vs 0.4, p < 0.01). In addition, a significantly higher percentage of PsO patients with treated anxiety/depression had comorbid hypertension, hyperlipidemia, or psoriatic arthritis (Supplementary Appendix 5) than their matched controls. The top three most commonly used concomitant medications were opioids/narcotics, respiratory medications, and anticholinergic agents. Concomitant use of opioids/narcotics was 1.9-fold higher (p < 0.01) among PsO patients with treated anxiety/depression than PsO patients without anxiety/depression. Similarly, anticholinergic use was 2-fold higher (p < 0.01) and respiratory medication use was 1.5-fold higher (p < 0.01) among PSO patients with treated anxiety/depression.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of matched moderate-to-severe PsO patients with treated anxiety/depression vs without anxiety/depression.

Costs attributable to treated anxiety/depression among PsO patients

On average, PsO patients with treated anxiety/depression incurred $8,077 (p < 0.01) higher unadjusted annual all-cause healthcare costs, with an incremental difference of $7,314 (91%) due to medical costs and $763 (9%) due to prescription costs (). Differences in costs were driven by a higher percentage of treated anxiety/depression PsO patients with all-cause hospitalizations (16.6% vs 8.6%, p < 0.01), ER visits (24.1% vs 12.2%, p < 0.01), physician office visits (99.6% vs 98.4%, p < 0.01), and other outpatient services (99.1% vs 97.2%, p < 0.01) than their matched controls. After adjusting for comorbid conditions, the incremental all-cause healthcare costs associated with treated anxiety/depression were $5,781 (p < 0.01).

Table 2. Annual all-cause and PsO-related healthcare costs of matched moderate-to-severe PsO patients with treated anxiety/depression vs without anxiety/depression.

No significant difference in total unadjusted PsO-related healthcare costs (p = 0.24) were observed between PsO patients with treated anxiety/depression and those with no anxiety/depression, although PsO patients with treated anxiety/depression had higher PsO-related medical costs ($2,489 vs $1,934, p < 0.01). Results were consistent after adjusting for comorbid conditions.

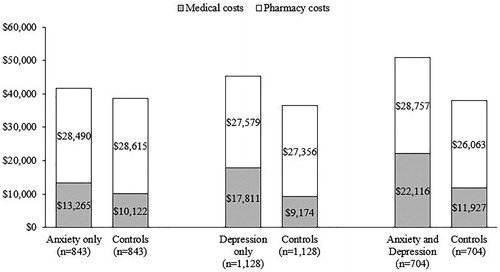

In the stratification analysis of PsO patients with treated anxiety/depression, costs associated with both anxiety and depression, depression only, or anxiety only were assessed. Compared with PsO patients without anxiety or depression, unadjusted total all-cause healthcare costs were $12,884 (p < 0.01) higher for patients with both anxiety and depression, $8,859 (p < 0.01) higher for patients with depression only, and $3,018 (p = 0.09) higher for patients with anxiety only ().

Among the relatively small sub-set with absenteeism records (n = 122), PsO patients with treated anxiety/depression had a mean of 97 (373 vs 276, p = 0.04) more work hours lost and $1,773 ($7,919 vs $6,146, p = 0.02) higher indirect costs due to absenteeism than matched PsO controls. Among patients with available short-term disability records (n = 110), PsO patients with treated anxiety/depression had a mean of 8 (59 vs 50, p = 0.42) more lost workdays and $1,195 ($6,836 vs $5,641, p = 0.26) higher indirect costs due to disability than matched PsO controls.

Discussion

Findings from this study add to the evidence that the prevalence and burden of psychiatric comorbidity, such as anxiety and depression, is significant among patients with moderate-to-severe PsO. Among the commercially-insured study population identified in years 2014–2016, prevalence of anxiety and depression increased overall and was significantly higher among patients with moderate-to-severe PsO compared with matched controls without PsO, ranging from 18.2–19.6% vs 12.2–13.1%. Our findings are higher, but directionally consistent with those from Han et al.Citation13, in which the prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities (based on diagnoses codes present in claims data, as well as treatments) among moderate-to-severe PsO patients matched to non-PsO controls, was examined from 2003 to 2004. In this earlier study, the prevalence of depression and anxiety were 9.2% and 6.9%, respectively, which were 3.9% and 2.5% higher, respectively, than rates reported for matched non-PsO controls. In addition, the proportions of patients with treated depression (6.1% vs 0.9%) and treated anxiety (5.0% vs 0.8%) were also higher among patients with moderate-to-severe PsO vs matched controls, respectivelyCitation13. Another retrospective claims database analysis of moderate-to-severe PsO patients identified between January 2007 and March 2012 by Feldman et al.Citation17 reported a 1-year prevalence of depression and anxiety of 9.1% and 6.3%, respectively, both of which were significantly higher than observed in the matched non-PsO cohorts. In our study examining more recent claims data, prevalence for anxiety and depression was higher than those reported by Han et al. and Feldman et al. among both PsO patients and matched non-PsO controls. This is consistent with data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health showing the prevalence of depression has increased from 2005 to 2015 in the USCitation18, and may explain the somewhat higher rates of anxiety and depression observed in the current study. Trends observed in our study from years 2014 to 2016 are consistent with continuation of this national trend.

We also measured the prevalence of MDD, one of the most common mental disorders in the US. While our results were generally consistent with those from a previous study in which a prevalence of 5.7% for MDD was reported among PsO patients during the time period of 2008–2014Citation19, our study found the prevalence of MDD among patients with moderate-to-severe PsO is increasing. Other studies using administrative claims data have also reported higher incidence rates of anxiety and depression for those with the autoimmune diseases of rheumatoid arthritisCitation20 and irritable bowel syndromeCitation21 compared to the general population.

Our findings also show that PsO patients with treated anxiety/depression incur substantial economic burden relative to PsO patients without treated anxiety/depression (unadjusted incremental all-cause healthcare cost: $8,077). In particular, all-cause healthcare costs were $12,884 higher for patients with both anxiety and depression, $8,859 higher for patients with depression only, and $3,018 higher for patients with anxiety only, all compared to PsO patients without anxiety or depression. Han et al.Citation13 also found all-cause healthcare costs to be $7,275 higher for moderate-to-severe PsO patients with psychiatric disorders (anxiety, depression, as well as others, such as bipolar disorder) compared to those of PsO patients without psychiatric disorders. Feldman et al.Citation9 reported incremental all-cause healthcare costs of $6,765 (2011 USD) for PsO patients with depression and $4,181 (2011 USD) for PsO patients with anxiety; however, 76% of the population in this study had mild disease, so it is less comparable with the population in our study.

For comparison of costs attributed to anxiety and depression in another patient group, Wallace et al.Citation22 reported, for patients with comorbid diabetes and hypertension, incremental all-cause healthcare costs of $8,709 for those who also have depression and anxiety, $4,607 for those who have depression only, and $2,481 for patients who have anxiety only relative to those who do not have depression or anxiety. Wallace et al.Citation22 collected study sample data during 2013–2015 from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, which includes patients with other insurance types, such as Medicare and Medicaid, and may account for the lower costs observed compared to those of the all commercially-insured population of the current study. Additionally, prescription costs in our study accounted for the major component of costs among PsO patients. However, these costs were similar between patients with treated anxiety/depression vs those without anxiety/depression, indicating the difference in total healthcare costs between the two groups was due largely to the use of medical services.

We also assessed the indirect costs associated with absenteeism and short-term disability in a sub-group of patients. Patients with treated anxiety and/or depression lost more days due to absence or short-term disability, resulting in higher indirect costs than patients with no anxiety or depression. Feldman et al.Citation9 reported significantly higher indirect costs due to short-term disability; $997 (2011 USD) higher among PsO patients with comorbid depression than those without depression. However, while patients with anxiety had higher short-term disability costs of $268 than those without anxiety, the difference was not statistically significant. The indirect costs reported by Feldman et al.Citation9 were likely lower than those from the current study because they were assessed among the overall PsO population, rather than a population diagnosed with PsO and receiving treatment for this condition.

Limitations

Results of this study should be interpreted in light of certain limitations. As with all retrospective claims database analyses, administrative claims data are collected for the purpose of facilitating payment for healthcare services; therefore, definitive diagnoses and data on disease severity are not available. To mitigate misclassification bias, patients in the treated anxiety and/or depression group were required to have both a diagnosis and related medications to ensure patients truly had PsO and anxiety/depression. Such definitions are widely used in retrospective claims-based studiesCitation23,Citation24. However, prevalence estimates from this study are still likely lower than the actual prevalence due to undiagnosed or untreated patients. For this study, we did not exclude patients with PsA from the PsO cohorts since greater than one-third of PsO patients also had a diagnosis of PsA (Supplementary Appendix 5). This may have been a source of confounding regarding the main comparison groups of the cost analyses. However, other recent studies of PsO patients have also retained patients with PsACitation9,Citation10,Citation17.

Indirect costs may be under-estimated in our study as information regarding presenteeism was not available in the database and were based on reported absenteeism and short-term disability only. Information on specific work activities are not available in the claims data and the sub-set of patients linked to the HPM data was small compared to the full analysis. Thus, our findings on absenteeism and short-term disability should be interpreted with this in mind. Furthermore, prescriptions paid entirely out of pocket may not be captured in the data, which may lead to potential under-estimation of prescription costs. In addition, while the claims database used for this study is large, it includes only the commercially insured population with health plans sponsored by employers. Thus, findings from our study may not apply to other real-world populations such as PsO patients with other or no insurance coverage, and the prevalence of anxiety and depression among PsO patients reported may not reflect populations with elderly or younger patients that are not sufficiently represented in the data source.

The strengths of this study include the large sample size of patients from the IBM MarketScan Commercial database, which is national in scope and contains claims information from many of the largest employer-sponsored commercial health plans in the US. The database is constructed to create a large sample with a high level of diversity, while also representing the overall population in the managed care setting. The administrative claims data also provide the most up-to-date longitudinal information, allowing exploration of questions of interest using recent data.

Conclusions

In a commercially insured US population, the prevalence of anxiety and/or depression was higher in moderate-to-severe PsO patients than those without PsO. Moderate-to-severe PsO patients with anxiety and/or depression incurred greater economic burden compared to matched PsO patients without anxiety/depression, which was primarily driven by greater use of medical services. While further research is needed to confirm, PsO treatments that help relieve psychiatric symptoms, such as anxiety and depression, have the potential to further improve patient quality-of-life and reduce the incremental economic burden associated with such comorbid conditions.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was supported by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

Declaration of financial/other interests

QC, AT, BW, and EM are employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, and hold stock in Johnson and Johnson. The peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work. In addition, a reviewer on this manuscript has disclosed receiving support from Janssen, as well as research, speaking and/or consulting support from a variety of companies, including Galderma, GSK/Stiefel, Almirall, Alvotech, Leo Pharma, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Mylan, Celgene, Pfizer, Ortho Dermatology, Abbvie, Samsung, Janssen, Lilly, Menlo, Merck, Novartis, Regeneron, Sanofi, Novan, Qurient, National Biological Corporation, Caremark, Advance Medical, Sun Pharma, Suncare Research, Informa, UpToDate, and National Psoriasis Foundation. This reviewer also consults for others through Guidepoint Global, Gerson Lehrman, and other consulting organizations. Another reviewer on this manuscript discloses serving as a consultant for BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen Biologics, Novartis Corp, UCB (DSMB), Sanofi, and Pfizer Inc.; receiving research grants (to the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania) from Abbvie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Novartis Corp, Celgene, Ortho Dermatologics, and Pfizer Inc.; and receiving payment for continuing medical education work related to psoriasis that was supported indirectly by Lilly, Ortho Dermatologics, and Novartis. The reviewers have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Previous presentations

Partial data were presented at the Fall Clinical Dermatology Conference October 18–21, 2018 in Las Vegas, NV.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (52.5 KB)Acknowledgements

Jay Lin, Novosys Health, Greenbrook, NJ, and Christopher D. Pericone, Janssen Scientific Affairs, provided medical writing support.

References

- Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:512–516.

- Brezinski EA, Dhillon JS, Armstrong AW. Economic burden of psoriasis in the United States: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:651–658.

- Vanderpuye-Orgle J, Zhao Y, Lu J, et al. Evaluating the economic burden of psoriasis in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:961–967 e5.

- Ferreira BR, Pio-Abreu JL, Reis JP, et al. Analysis of the prevalence of mental disorders in psoriasis: the relevance of psychiatric assessment in dermatology. Psychiat Danub. 2017;29:401–406.

- Dowlatshahi EA, Wakkee M, Arends LR, et al. The prevalence and odds of depressive symptoms and clinical depression in psoriasis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1542–1551.

- Dauden E, Castaneda S, Suarez C, et al. Clinical practice guideline for an integrated approach to comorbidity in patients with psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1387–1404.

- Fleming P, Bai JW, Pratt M, et al. The prevalence of anxiety in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review of observational studies and clinical trials. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:798–807.

- Kurd SK, Troxel AB, Crits-Christoph P, et al. The risk of depression, anxiety, and suicidality in patients with psoriasis: a population-based cohort study. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:891–895.

- Feldman SR, Tian H, Gilloteau I, et al. Economic burden of comorbidities in psoriasis patients in the United States: results from a retrospective U.S. database. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:337.

- Foster SA, Zhu B, Guo J, et al. Patient characteristics, health care resource utilization, and costs associated with treatment-regimen failure with biologics in the treatment of psoriasis. JMCP. 2016;22:396–405.

- Ferreira BI, Abreu JL, Reis JP, et al. Psoriasis and associated psychiatric disorders: a systematic review on etiopathogenesis and clinical correlation. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016;9:36–43.

- Connor CJ, Liu V, Fiedorowicz JG. Exploring the physiological link between psoriasis and mood disorders. Dermatol Res Pract. 2015;2015:1.

- Han C, Lofland JH, Zhao N, et al. Increased prevalence of psychiatric disorders and health care-associated costs among patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:843–850.

- Griffiths CEM, Jo SJ, Naldi L, et al. A multidimensional assessment of the burden of psoriasis: results from a multinational dermatologist and patient survey. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:173–181.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. Median Usual Weekly Earnings: United States Department of Labor; 2018 [updated October 16, 2018; cited 2018]. Available from: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/wkyeng.toc.htm

- Soliman AM, Surrey E, Bonafede M, et al. Real-world evaluation of direct and indirect economic burden among endometriosis patients in the United States. Adv Ther. 2018;35:408–423.

- Feldman SR, Zhao Y, Shi L, et al. Economic and comorbidity burden among patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. JMCP. 2015;21:874–888.

- Weinberger H, Gbedemah M, Martinez AM, et al. Trends in depression prevalence in the USA from 2005 to 2015: widening disparities in vulnerable groups. Psychol Med. 2018;48:1308–1315.

- Shah K, Mellars L, Changolkar A, et al. Real-world burden of comorbidities in US patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:287–292 e4.

- Marrie RA, Hitchon CA, Walld R, et al. Increased burden of psychiatric disorders in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2018;70:970–978.

- Bernstein CN, Hitchon CA, Walld R, et al. Increased burden of psychiatric disorders in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25:360–368.

- Wallace K, Zhao X, Misra R, et al. The humanistic and economic burden associated with anxiety and depression among adults with comorbid diabetes and hypertension. J Diabetes Res. 2018;2018:4842520.

- Dobson-Belaire W, Goodfield J, Borelli R, et al. Identifying psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis patients in retrospective databases when diagnosis codes are not available: a validation study comparing medication/prescriber visit-based algorithms with diagnosis codes. Value Health. 2018;21:110–116.

- Marrie RA, Walker JR, Graff LA, et al. Performance of administrative case definitions for depression and anxiety in inflammatory bowel disease. J Psychosom Res. 2016;89:107–113.