Abstract

Aims: To determine the clinical effectiveness and safety of venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis using US- and Europe-approved anticoagulants relative to extended-duration VTE prophylaxis with betrixaban. Low molecular weight heparins (LMWHs), unfractionated heparin (UFH), fondaparinux sodium and placebo were each compared to betrixaban, as standard-duration VTE prophylaxis for hospitalized, non-surgical patients with acute medical illness at risk of VTE.

Materials and methods: A systematic literature review was conducted up to June 2019 to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of VTE prophylaxis in hospitalized, non-surgical patients with acute medical illness at risk of VTE. Studies that reported the occurrence of VTE events (including death) and, where possible, major bleeding, from treatment initiation to 20–50 days thereafter were retrieved and extracted. A Bayesian fixed effect network meta-analysis was used to estimate efficacy and safety of betrixaban compared with standard-duration VTE prophylaxis.

Results: Seven RCTs were analyzed which compared betrixaban, LMWHs, UFH, fondaparinux sodium, or placebo. There were significantly higher odds (median odds [95% credible interval]) of VTE with LMWHs (1.38 [1.12–1.70]), UFH (1.60 [1.05–2.46]), and placebo (2.37 [1.55–3.66]) compared with betrixaban. There were significantly higher odds of VTE-related death with placebo (7.76 [2.14–34.40]) compared with betrixaban. No significant differences were observed for the odds of major bleeding with all comparators, VTE-related death with any active standard-duration VTE prophylaxis, or of VTE with fondaparinux sodium, compared with betrixaban.

Limitations and conclusions: In this indirect comparison, betrixaban was shown to be an effective regimen with relative benefits compared with LMWHs and UFH. This indicates that betrixaban could reduce the burden of VTE in at-risk hospitalized patients with acute medical illness who need extended prophylaxis, though without direct comparative evidence, stronger conclusions cannot be drawn.

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a common cause of morbidity and mortality, particularly in patients hospitalized with an acute medical illness. A model developed in the US estimated that 196,134 VTE-related events occurred in US acutely ill hospitalized patients in 2003Citation1. Approximately one third of all symptomatic VTE results in deathCitation2. Though many patients survive VTE, some require intensive care and treatment which can last for several months. Furthermore, not all survivors of VTE are restored to their previous state of health; approximately 30% of surviving patients will experience a recurrent VTE episode within 10 years of their first episodeCitation3. Additionally, surviving patients can experience severe complications including chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) and post-thrombotic syndrome (PTS), which reduce quality-of-life and are costly to treatCitation4,Citation5.

Though the highest risk of VTE in the acute medically ill population occurs during hospitalization, the risk persists following discharge. It is reported that 45–75% of all VTEs in the acute medically ill population occur post-dischargeCitation6–9. Therefore, it is necessary that thromboprophylaxis continues beyond hospitalization in many patients, when standard-duration thromboprophylaxis typically ends, to minimize the risk of VTE. This is particularly important among those who have multiple risk factors for VTE, including previous hospitalization for an acute medical illness, increased age, reduced mobility, history of cancer or VTE, and obesity. Previous studies have investigated extended-duration VTE prophylaxis in patients hospitalized with an acute medical illness to address the risk of VTE after hospital dischargeCitation10–12. However, in these studies extended-duration prophylaxis led to increased major bleeding, causing the treatment’s harms to exceed its benefits. The duration of hospitalization for patients with an acute medical illness has fallen in the USCitation13–16. At the same time, the number of medical hospitalizations in patients aged 45–74 has increasedCitation17, and is likely to increase further as the population agesCitation18. These changes increase the need for a VTE prophylaxis regimen which may protect high risk patients from VTE events following hospital discharge, without raising their risk of major bleeding.

Betrixaban is a factor Xa inhibitor which was the first and only direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) to be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for extended-duration VTE prophylaxis of hospitalized, acutely ill medical patientsCitation19. Whilst there have been studies of extended-duration VTE prophylaxis with other DOACs, none have been approved in any market. Hence, it is of great interest to understand how standard-duration VTE prophylaxis compares to betrixaban. In the Acute Medically Ill VTE Prevention with Extended Duration Betrixaban (APEX) study (NCT01583218), betrixaban demonstrated effective extended-duration VTE prophylaxis lasting up to 42 days without an increase in the risk of major bleeding, compared with standard-duration VTE prophylaxis lasting up to 14 days with enoxaparin, a low molecular weight heparin (LMWH)Citation20. However, no studies have compared betrixaban with alternative VTE prophylaxis (including LMWHs other than enoxaparin, unfractionated heparin (UFH), fondaparinux sodium), or placebo. LMWHs other than enoxaparin are of interest since they are also recommended for prophylactic use in the US, the UK, and other marketsCitation21–23.

The purpose of this study was to determine the relative clinical effectiveness of extended-duration VTE prophylaxis with betrixaban from hospitalization through post-discharge compared with standard-duration VTE prophylaxis regimens which cease during hospitalization or at hospital discharge, using other available interventions, including LMWHs, UFH, fondaparinux sodium, and placebo, for hospitalized, non-surgical patients with acute medical illness at risk of VTE evaluated 20–50 days following the initiation of prophylaxis.

Methods

A systematic literature review (SLR) was performed to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of betrixaban and standard-duration VTE prophylaxis. This SLR was conducted to identify studies to be considered for inclusion in a network meta-analysis (NMA).

Identification of relevant studies

We sought studies which answered the following review question: What is the efficacy and safety of betrixaban, LMWHs, UFH, fondaparinux sodium, and placebo in adults who are hospitalized for an acute medical condition and are at risk of VTE?

We identified and updated a clinical evidence review performed in December 2008, which related to interventions for thromboprophylaxis in hospitalized patients and was performed by the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE)Citation24. Three search iterations were undertaken to update the 2008 NICE SLR, with the first performed in December 2016, the second performed in December 2017, and the third performed in June 2019. The search strategy presented in Supplementary Appendix 1 was used to search EMBASE, Medline, Medline® In-Process, HTA Database, NHS Economic Evaluation Database, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (Cochrane Library). Complementary “grey” literature sources were also searched to identify data from recent or ongoing trials during the past 3 years that had not been archived in a database. Unpublished or non-journal “grey” literature sources included: clinicaltrials.gov, the manufacturer’s repository of evidence, manufacturers of comparator products’ websites, and conference proceedings. All references identified were deduplicated after search compilation. The first and second iteration of searches were reviewed by two independent health economists. Reviewers identified relevant search results by assessing: title and abstract in the first pass of search results, and the entire publication during the second pass. Any discrepancies between the reviewers in the first and second iterations were discussed and resolved with a third, independent reviewer, in alignment with the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination’s guidance for undertaking reviews in healthcareCitation25. The third iteration of searches was a pragmatic SLR update to ensure that the search is up to date at the time of preparing for this manuscript and all essential studies were included in the analyses. As such, it was reviewed by one health economist only at first and second pass.

The studies were assessed by applying eligibility criteria, which were defined according to the PICOS (population, interventions, comparators, outcomes and study type) principleCitation25. Included studies were performed in acute, medically ill hospitalized adult patients at risk of VTE; compared a combination of betrixaban, fondaparinux sodium, LMWHs, UFH, no treatment or placebo; reported mortality, VTE incidence or adverse events; and were RCTs. The full eligibility criteria can be found in Table S1 (Supplementary Appendix 2).

Data extraction and quality assessment

All studies identified by the SLR were extracted by one reviewer and assessed independently by another reviewer. A pre-prepared extraction grid was designed to collect data from each study regarding: primary study reference, eligibility criteria, settings, trial drugs, concomitant medications, statistical methods, participant baseline characteristics, and all relevant recorded outcomes. During the feasibility assessment which followed extraction, studies were assessed according to Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC) guidance to identify heterogeneity across studies. This entailed a comparison of: study designs, population characteristics, treatment types and durations, and outcomes, to ensure comparability with the APEX studyCitation26. Baseline demographics which informed the assessment of heterogeneity are shown for all studies considered in Table S2 (Supplementary Appendix 3). The studies were then assessed for bias using the Cochrane guidanceCitation27,Citation28.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed using WinBUGS (version 1.4.3, Imperial College and Medical Research Council, UK) and RStudio (version 1.0.143, RStudio, Inc., Boston, MA)Citation29,Citation30. WinBUGS was run via RStudio using the package R2WinBUGSCitation31. The outcomes considered were: VTE, VTE-related death, major bleeding, pulmonary embolism (PE), asymptomatic deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and symptomatic DVT reported 20–50 days following the initiation of thromboprophylaxis. For each outcome analyzed, median odds ratios with 95% credible intervals (CrI) for each comparator were generated relative to betrixaban, since it was of interest to know how other treatments compared to betrixaban. Uncertainty was quantified using 95% credible intervals, which are the Bayesian analog of CrIs, in accordance with NICE Decision Support Unit guidance which used this approach to quantify uncertainty of model results. All outcomes were evaluated using a standard Bayesian fixed effect NMA on the logit scaleCitation32. The treatment effects of all LMWHs were assumed identical, aligning with NICE clinical guidelines for VTE which assume a class effect among LMWHsCitation22. Standard non-informative priors were used for treatment effects and study-specific baseline effectsCitation32. Convergence of all parameters (including treatment effects, study-specific baseline effects and odds ratios) were assessed using trace plots and Brooks-Gelman-Rubin plots for each modelCitation33. If there were zero events, and hence convergence issues, a continuity correction was madeCitation32. To handle other issues with convergence, the variance of the prior distributions were reduced. Model fit was assessed using median residual deviance and number of unconstrained data points.

Sensitivity analysis

In the base case, studies with a placebo arm which were performed prior to the year 2000 were excluded. The year 2000 was an arbitrary threshold between the two earliest identified placebo-controlled studies (Belch et al., 1981, and PREVENT 2002), which were conducted over 20 years apartCitation34,Citation35. The threshold was applied to avoid exclusion of more recent studies conducted, since best supportive care had improved relative to older studies. These more recent studies were expected to show relatively smaller additional benefits of pharmacological prophylaxis compared to best supportive care, and therefore show newer treatments to be relatively less efficacious compared to placebo.

To examine this threshold’s effect, studies performed prior to 2000 that included a placebo arm were included in a sensitivity analysis. Additionally, to understand differences in treatment effect across all definitions of DVT, a sensitivity analysis was performed combining all DVT outcomes reported 20–50 days after initiation of thromboprophylaxis in one measure. If a study reported multiple definitions of DVT, each type of recorded DVT was considered to be from a unique study and was added to the composite measure. Finally, to examine the effect of only using full dose betrixaban, a sensitivity analysis was performed excluding all betrixaban patients with severe renal impairment or those that received a concomitant P-glycoprotein inhibitor who received half-doses of the study medications in the APEX study.

Results

Systematic literature review

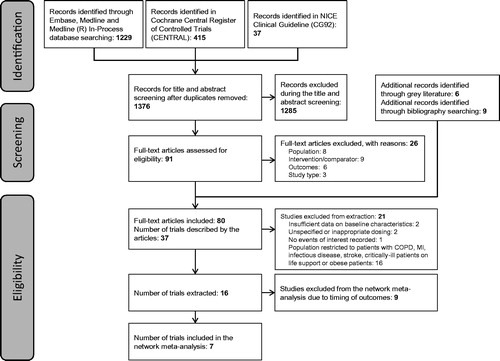

The SLR identified 1,681 references. shows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram demonstrating the flow of reference identification to NMA inclusion. The 16 unique studies identified from the SLR which were considered for NMA inclusion evaluated betrixaban, LMWHs (enoxaparin, nadroparin, dalteparin, and certoparin), UFH, fondaparinux sodium, and placebo.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Among the 16 studies identified, the timing of outcomes was a major confounding factor identified in the heterogeneity assessment. In order to appropriately compare outcomes reported across studies with outcomes reported for betrixaban for extended-duration VTE prophylaxis in APEX, it was determined that outcomes not reported 20–50 days following the initiation of pharmacological thromboprophylaxis would not be suitable for inclusion in the NMA. Therefore, nine studies were excluded from inclusion in the NMA on this basisCitation36–44. Whilst study design, population characteristics, treatment arms, and outcomes were thoroughly compared, there were no aspects that were deemed to be major confounding factors in the heterogeneity assessment. There was mild concern about variation in duration of active treatment and follow-up time, however this was not deemed to be limiting as all treatment durations received were within their license. Hence, heterogeneity assessment did not prompt exclusion of any further studies.

provides a summary of the studies included in the NMA. Supplementary Table S3 provides definitions of each of the outcomes included in or excluded from the analysis, by study. Additionally, Supplementary Table S2 provides a summary of the demographics of patients enrolled in each study included in the analysis. The definitions of acute medically ill; average population age; and average population weight were identified as minor confounding factors in the heterogeneity assessment, though no study was excluded from the NMA on this basis.

Table 1. Summary of studies included in the network meta-analysis.

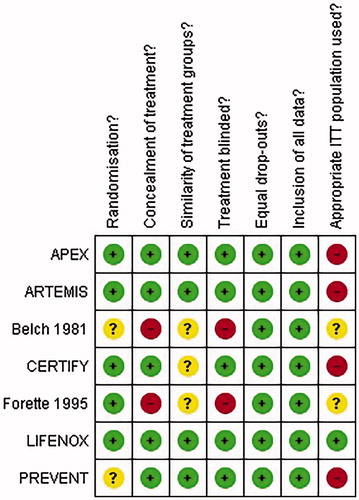

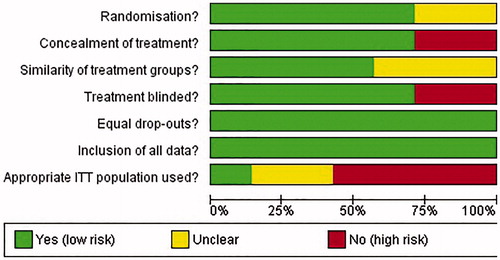

The results of the bias assessment are summarized in . All studies were randomized, and randomization method was evaluated as appropriate where reportedCitation20,Citation45–48; Belch 1981 and PREVENT did not report the method of randomization so appropriateness was unclearCitation34,Citation35. Concealment of treatment was adequate in all studiesCitation20,Citation35,Citation45,Citation46,Citation48, except Belch et al.Citation34 and Forette and WolmarkCitation47, which were open label. In most studies, the groups enrolled were similar at baselineCitation20,Citation35,Citation45,Citation48; though information on baseline characteristics was inadequate in Belch et al.Citation34, CERTIFYCitation46 and Forette and WolmarkCitation47. There were similar drop-out rates amongst the study arms included and it does not appear that any data has been omitted from the reported resultsCitation20,Citation34,Citation35,Citation45–48. The intention-to-treat (ITT) populations were reported in LIFENOXCitation48. In APEX, ARTEMIS, CERTIFY, and PREVENT, the ITT populations were restricted by results of a venographyCitation20,Citation35,Citation45,Citation46. The appropriate use of the ITT populations was not clear in Belch et al.Citation34 and Forette and WolmarkCitation47. The graph displaying the risk of bias amongst studies included in the NMA is presented in .

Base case analyses results

The network diagrams for each analysis can be found in Figures S1–S8 (Supplementary Appendix 5).

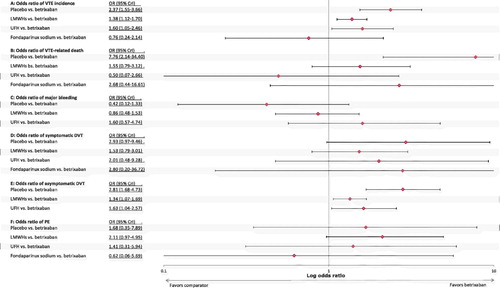

Four studies and a total of 14,024 participants were included in the analysis of VTECitation20,Citation35,Citation45,Citation46. There were significantly higher odds (median odds [95% CrI]) of a VTE with LMWHs (OR = 1.38; 95% CrI = 1.12–1.70), with UFH (OR = 1.60; 95% CrI = 1.05–2.46), or with placebo (OR = 2.37; 95% CrI = 1.55–3.66), relative to betrixaban (). There was no significant difference between betrixaban and fondaparinux sodium in the odds of VTE.

Five studies and a total of 23,346 participants were included in the VTE-related death analysisCitation20,Citation35,Citation45,Citation46,Citation48. There were significantly higher odds of a VTE-related death with placebo relative to betrixaban (OR = 7.76; 95% CrI = 2.14–34.40) (). The odds of a VTE-related death with LMWHs, UFH, and fondaparinux sodium were not significantly different to betrixaban.

Four studies and a total of 14,283 participants were included in the major bleeding analysisCitation20,Citation35,Citation46,Citation47. There were no significant differences in the odds of major bleeding with placebo, LMWHs, or UFH compared with betrixaban (). It was not possible to form a comparison against fondaparinux sodium, as major bleeding was only reported as an outcome in ARTEMIS up to 2 days after treatment, which is a maximum of 16 days—outside of the Day 20–50 inclusion.

Four studies and a total of 14,855 participants were included in the symptomatic DVT analysisCitation20,Citation35,Citation45,Citation46. There was no significant difference in the odds of symptomatic DVT with betrixaban compared with any of the included comparators. The median odds ratio of comparators relative to betrixaban was greater than 1.5 in all cases (), suggesting higher (albeit non-significant) odds of symptomatic DVT with placebo, LMWHs, UFH, and fondaparinux sodium compared with betrixaban.

Three studies and a total of 13,142 participants were included in the asymptomatic DVT analysisCitation20,Citation35,Citation46. There were significantly higher odds of an asymptomatic DVT with LMWHs (OR = 1.34; 95% CrI = 1.07–1.69), UFH (OR = 1.63; 95% CrI = 1.04–2.57), and placebo (OR = 2.81; 95% CrI = 1.68–4.73) (). It was not possible to form a comparison against fondaparinux sodium as asymptomatic DVT was only measured to Day 15 in ARTEMIS.

Five studies and a total of 14,898 participants were included in the PE analysisCitation20,Citation35,Citation45–47. The odds of a PE were not significantly different with betrixaban compared with any of the included comparators (). The median odds ratio of LMWHs, UFH, and placebo relative to betrixaban was greater than 1.0 (), suggesting higher (albeit non-significant) odds of PE with placebo, LMWHs, and UFH compared with betrixaban. On the other hand, the median odds ratio of fondaparinux sodium relative to betrixaban was less than 1.0 (), suggesting lower (albeit non-significant) odds of PE with fondaparinux sodium compared with betrixaban.

For each outcome, the median residual deviance (7.4, 10.1, 6.6, 5.3, and 10.1 for VTE, major bleeding, symptomatic DVT, asymptomatic DVT, and PE, respectively) was close to the number of data points used (8, 8, 8, 6, and 10, respectively). This indicates that the models are a good fit to the data. For VTE-related death, the median residual deviance was 21.2, which is much higher than the number of data points used (10). This indicates that the VTE-related death model may not be a good fit to the data.

Sensitivity analysis results

Only one study, Belch et al.Citation34, was completed before 2000 with a placebo arm. The only outcome that this study contributed to was PE. Therefore, the PE analysis was rerun, with Belch et al.Citation34 included as a sensitivity analysis, including a total of 14,998 participantsCitation20,Citation35,Citation45–47. The odds ratio of a PE with placebo relative to betrixaban was greater than in the base case, though it was lower for the other comparators. The significance of the results did not change and neither did the preference for any treatment over betrixaban.

The sensitivity analysis that considered all types of recorded DVT included 11 different DVT results from five studiesCitation20,Citation35,Citation45–47. There were 37,249 participants included in the analysis. The odds of any type of DVT were significantly greater with LMWHs (OR = 1.36; 95% CrI = 1.10–1.70), UFH (OR = 1.63; 95% CrI = 1.20–2.21), and placebo (OR = 2.74; 95% CrI = 1.90–4.00) compared with betrixaban. Though the median odds ratio of any DVT relative to betrixaban was above one for fondaparinux sodium, the difference in odds was not significant.

For the sensitivity analyses considering only patients on the full study dose from the APEX study, the total number of studies included in each analysis remained the same. There were, however, fewer patients for each analysis due to the exclusion of betrixaban patients with severe renal impairment and patients taking P-glycoprotein inhibitors from the APEX study. There were 12,387, 21,709, 12,738, 11,505, 13,218, and 13,261 participants included in the analysis of VTE, VTE-related death, major bleeding, asymptomatic DVT, symptomatic DVT, and PE, respectively. Mostly, the significance of differences between treatments remained the same as in the full-population analyses. The only changes were of the odds ratio of a symptomatic DVT with placebo (OR = 3.08; CrI = 1.05–9.28) and of a PE with LMWH (OR = 3.74; CrI = 1.36–13.32) relative to betrixaban. This sensitivity analysis showed significantly lower odds of a VTE for betrixaban compared with placebo and LMWH.

Discussion

The results of the NMA showed a significant reduction in VTE morbidity and mortality with betrixaban compared with LMWH, UFH, and placebo. Reducing VTE events would reduce recurrent VTE morbidity and complications such as CTEPH and PTS, which are very costly to manage and severely impact quality-of-lifeCitation49,Citation50. This further indicates that extended VTE prophylaxis with betrixaban may lead to prolonged patient health benefits.

Additionally, the results showed a significant reduction in asymptomatic DVT with betrixaban compared with LMWHs, UFH, and placebo. Asymptomatic DVT is associated with chronic complications such as PTSCitation51, and may progress to symptomatic DVTCitation52, which requires anticoagulation treatment lasting months and leads to rehospitalization for many patients. Symptomatic DVT is also associated with a risk of recurrent VTE and complications such as PTS. It is evident that reducing asymptomatic DVT may reduce risk of future, more serious events which are associated with poorer quality-of-life and increased healthcare costs. Furthermore, following an asymptomatic DVT event, patients have an increased risk of death compared with patients who have not experienced a DVT eventCitation53.

There was a strong trend of fewer symptomatic DVT and PE events with betrixaban compared with the other treatments available, with the point estimate of all odds ratios favoring betrixaban with few exceptions. Many of the results from the analysis did not achieve statistical significance, which may be due to a lack of head-to-head evidence. The conclusions of the analysis could have been stronger had direct evidence comparing betrixaban to placebo, UFH, or fondaparinux sodium been available.

This analysis demonstrated no significant difference between betrixaban and any of the comparators for the occurrence of major bleeding. This benefit in safety was also seen in the APEX study, as there was no significant difference in major bleeding between betrixaban and enoxaparinCitation20. Adverse events which are associated with VTE prophylaxis such as major bleeding (which includes intracranial hemorrhage) can be costly to treat and are associated with reduced long-term quality-of-life. However non-major bleeding is increased in extended prophylaxis and, therefore, appropriate management of the risk-benefit ratio and identification of at-risk patients for extended VTE-prophylaxis are essential in addressing the growing need for VTE prophylaxis extending beyond hospitalizationCitation54–56.

The results of the NMA for betrixaban vs fondaparinux sodium are uncertain. The analysis showed no significant difference between the two regimens. This may indicate that betrixaban is not superior to fondaparinux sodium as extended-duration prophylaxis. However, the treatment effect of fondaparinux sodium was based only on the ARTEMIS trial. This trial had fewer participants compared with other trials included in the NMA. All DVT events recorded in the first 15 days were asymptomatic DVT detected by venography and the only symptomatic events recorded in the primary outcome of the trial were adjudicated fatal PE. Furthermore, there were no asymptomatic events recorded after the first 15 days that could be included in the analysis. Therefore, inclusion of ARTEMIS focused on reports of symptomatic events which were measured until Day 32. At the end of follow-up, the placebo arm reported twice as many fatal PE and 4-times more non-fatal PE events than the fondaparinux sodium arm, and both arms reported zero incidence of symptomatic DVT. These factors have contributed to uncertainty in the results for fondaparinux sodium in the NMA and may have led to an over-estimation of the treatment effect associated with fondaparinux sodium as the incidence of asymptomatic events has not been considered due to incompatible timing. Of note, however, a larger proportion of patients in the fondaparinux sodium arm experienced fatal PE (0.7% fatal PE for fondaparinux patients compared to, for example, 0.3% fatal VTE for betrixaban patients in APEX); as such, fewer patients in this arm remained alive for the duration of the trial to be at risk of non-fatal VTE events, possibly causing the burden of such events to be under-represented relative to the placebo armCitation39.

The main limitation of this analysis is the small number of studies that were available for comparison. In particular, studies of DOACs for extended VTE prophylaxis were not considered as they are not approved in this indication in any market, and many studies identified by the SLR were not suitable for comparison with the results of the APEX study as outcomes were not reported within the interval of 20–50 days following prophylaxis initiationCitation36–44. Overall, however, the timeframe of 20–50 days following the initiation of VTE prophylaxis enabled the selection of the most suitable and comparable studies based on the time at which patients were assessed in the APEX study (following completion of their extended-duration VTE prophylaxis regimen), enabling comparisons to be drawn with betrixaban.

Another limiting factor was the lack of head-to-head data available for betrixaban; had there been more studies completed for betrixaban against other treatments there would have been more data to form stronger conclusions.

Additionally, no adjustment was made for the duration of treatment in the different studies. This may have caused over-estimation of the benefits of longer-duration treatment, since such regimens provided a longer timeframe for treatment benefit to be observed. However, the treatment durations compared were all within their licensed indication, and therefore the differences in treatment duration are inherently linked to the differences in treatment effect.

Finally, the exclusion of studies containing placebo treatment conducted prior to the year 2000 to account for changing clinical practice in best supportive care may have overlooked bias due to changing methods to confirm clinical endpoints in studies over time. However, as all treatment arms within a study would use the same diagnostic measures, systematic differences in the method of diagnosing patients should not have affected the estimates of incremental treatment effect observed. Moreover, a feasibility assessment was conducted to investigate such heterogeneity, among other factors, and no major differences in the endpoint measures between studies were identified for relevant endpoints for each study. A sensitivity analysis including the Belch et al.Citation34 study confirmed that results were robust to the year of publication among studies included. The use of a fixed effect NMA enabled estimation of treatment effects in the included studies. A random effects model would be required to generalize the results beyond the included studies and remove any bias that may be attributed to anticipated confounding factors between the studies. However, due to the small number of studies and nature of VTE events, informative priors using external information would be needed for this kind of analysis. As such, fixed effect models have been used, limiting assessment of between-study heterogeneity, possibly producing artificially small credible intervals for results. The small number of studies also restricted the use of funnel plots for robust bias and quality assessment.

Conclusions

In this indirect comparison, extended-duration VTE prophylaxis from hospital admission through post-discharge with betrixaban was a comparatively safe and effective regimen. Results showed that betrixaban extended-duration VTE prophylaxis provides relative benefit with respect to the efficacy and safety outcomes considered, when compared to regimens for standard VTE prophylaxis. Given the need for an effective extended-duration VTE prophylaxis with a good safety profile, betrixaban shows potential to contribute to reducing the burden of VTE in hospitalized, non-surgical patients with acute medical illness at risk of VTE, however in the absence of direct comparative evidence stronger conclusions cannot be drawn.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This research was supported by Portola Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

VL, HG, and MF are employees of FIECON Ltd, a health-economics outcomes research agency, which performed the analyses presented in the manuscript, funded by Portola Pharmaceuticals, Inc. RN and IB were employees of Portola Pharmaceuticals, Inc, at the time of the research project. SR is a Research Fellow at The University of Sheffield and performed the analyses presented in the manuscript in collaboration with FIECON Ltd, funded by FIECON Ltd. ATC has received consulting fees, research support, and honoraria from AbbVie, ACI Clinical, Aspen, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boston Scientific, CSL Behring, Daiichi-Sankyo, GlaxoSmithKline, GLG, Guidepoint Global, Johnson and Johnson, Leo Pharma, Medscape, McKinsey, Navigant, ONO, Pfizer, Portola, Sanofi, Takeda, Temasek Capital, and TRN. A peer reviewer on this manuscript has disclosed receiving grants and honoraria from various pharma companies, including those developing, manufacturing, and marketing anti-coagulants. The peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Acknowledgements

Augusta Connor is thanked for her editing to bring the publication to press.

Previous presentations

The base case results were presented in a poster submitted to both the American College of Clinical Pharmacy (ACCP) and the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy in 2018. The abstract for the poster was published in the abstract book of the conference of ACCP. There has not yet been a full publication of the results.

Data availability statement

Raw data were generated at Portola Pharmaceuticals. Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (VL) on request.

Supplemental data for this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1080/13696998.2019.1645679.

Download MS Word (357 KB)References

- Piazza G, Fanikos J, Zayaruzny M, et al. Venous thromboembolic events in hospitalised medical patients. Thromb Haemost. 2009;102:505–510.

- Heit JA, Cohen AT, Andersen FA. Jr., Estimated annual number of incident and recurrent, non-fatal and fatal venous thromboembolism (VTE) events in the US. Blood. 2005;910.

- Heit JA, Spencer FA, White RH. The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;41:3–14.

- Pengo V, Lensing AWA, Prins MH, et al. Incidence of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension after pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2257–2264.

- Prandoni P, et al. The clinical course of deep-vein thrombosis. Prospective long-term follow-up of 528 symptomatic patients. Haematologica. 1997;82:423–428.

- Spyropoulos AC, Anderson FA, FitzGerald G, et al. Predictive and associative models to identify hospitalized medical patients at risk for VTE. Chest. 2011;140:706–714.

- Amin AN, Varker H, Princic N, et al. Duration of venous thromboembolism risk across a continuum in medically ill hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:231–238.

- Pendergraft T, Atwood M, Liu X, et al. Cost of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized medically ill patients. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70:1681–1687.

- Heit JA, Crusan DJ, Ashrani AA, et al. Effect of a near-universal hospitalization-based prophylaxis regimen on annual number of venous thromboembolism events in the US. Blood. 2017;130:109–114.

- Cohen AT, Spiro TE, Büller HR, et al. Rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:513–523.

- Goldhaber SZ, Leizorovicz A, Kakkar AK, et al. Apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis in medically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2167–2177.

- Hull RD, et al. Extended-duration venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients with recently reduced mobility: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:8–18.

- Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A, for Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Overview of hospital stays in the United States, 2012. 2014 [cited 2018 March 20]. Available from: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb180-Hospitalizations-United-States-2012.pdf

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Health at a glance 2017: OECD indicators. [cited 2018 March 20]. Available from: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/health_glance-2017-en.pdf?expires=1536312324&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=9A2183B01DA4247F63CA207618BB50BB

- US Department of Health and Human Services. CMS Statistics 2015. [cited 2018 May 24]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/CMS-Statistics-Reference-Booklet/Downloads/2015CMSStatistics.pdf

- US Department of Health and Human Services. CMS Statistics 2016. [cited 2018 May 24]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/CMS-Statistics-Reference-Booklet/Downloads/2016_CMS_Stats.pdf

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. Statistical Brief #225: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). 2017 [cited 2018 June 28]. Available from: www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb225-Inpatient-US-Stays-Trends.jsp.

- Jacobsen LA, Kent M, Lee M, et al. America’s aging population. Popul Bull. 2011;66(1):1–17. Available from: https://assets.prb.org/pdf11/aging-in-america.pdf (accessed 2018 June 28).

- Food and Drug Administration. FDA approved betrixaban (BEVYXXA, Portola) for the prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in adult patients. [cited 2018 March 20]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/InformationOnDrugs/ApprovedDrugs/ucm564422.htm

- Cohen AT, Harrington RA, Goldhaber SZ, et al. Extended thromboprophylaxis with betrixaban in acutely ill medical patients. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:534–544.

- ASH Clinical Practice Guidelines on Venous Thromboembolism, 04-Feb-2019. [Online]. Available from: /VTE/. [Accessed: 26-Feb-2019].

- NICE. Clinical Guideline. Venous thromboembolism in over 16s: reducing the risk of hospital-acquired deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism (Update) [Online]. 2017. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/indevelopment/gid-cgwave0795/consultation/html-content-2.

- Johnston A, Hsieh S-C, Carrier M, et al. A systematic review of clinical practice guidelines on the use of low molecular weight heparin and fondaparinux for the treatment and prevention of venous thromboembolism: Implications for research and policy decision-making. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0207410.

- NICE. Venous thromboembolism: reducing the risk for patients in hospital: clinical guideline. 2010, 2015 [cited 2016 October 27]. Available from: nice.org.uk/guidance/cg92

- Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Systematic reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. 2009 [cited 2016 October 20]. Available from: https://www.york.ac.uk/media/crd/Systematic_Reviews.pdf

- Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee. Guidelines for preparing a submission to the PBAC. 2010 [cited 2017 June 26]. Available from: https://pbac.pbs.gov.au/content/information/files/pbac-guidelines-version-5.pdf

- Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.3. Copenhagen (Denmark): The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration; 2014.

- Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC, et al. Chapter 8: assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, Altman DG, et al, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Version 5.1.0. 2011 [cited 2018 June 5]. Available from: www.handbook.cochrane.org

- Lunn DJ, Thomas A, Best N, et al. WinBUGS – a Bayesian modelling framework: concepts, structure, and extensibility. Stat Comput. 2000;10:325–337.

- RStudio Team. RStudio: integrated development for R. Boston (MA): RStudio, Inc; 2016. Available from: http://www.rstudio.com/.

- Sturtz S, Ligges U, Gelman A. R2WinBUGS: a package for running WinBUGS from R. J Stat Soft. 2005;12:1–16.

- Dias S, Welton NJ, Sutton AJ, et al. NICE DSU Technical Support Document 2: a generalised linear modelling framework for pairwise and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials; 2016 Sept [cited 2017 July 78]. Available from: http://scharr.dept.shef.ac.uk/nicedsu/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2017/05/TSD2-General-meta-analysis-corrected-2Sep2016v2.pdf.

- Brooks S, Gelman A. General methods for monitoring convergence of iterative simulations. J Comput Graphical Stat. 1998;7:434–455.

- Belch JJ, Lowe GD, Ward AG, et al. Prevention of deep vein thrombosis in medical patients by low-dose heparin. Scott Med J. 1981;26:115–117.

- Leizorovicz A, Cohen AT, Turpie AGG, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of dalteparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in acutely ill medical patients. Circulation. 2004;110:874–879.

- Bergmann JF, Neuhart E. A multicenter randomized double-blind study of enoxaparin compared with unfractionated heparin in the prevention of venous thromboembolic disease in elderly in-patients bedridden for an acute medical illness: the enoxaparin in medicine study group. Thromb Haemost. 1996;76:529–534.

- Mahé I, Bergmann JF, d’Azémar P, et al. Lack of effect of a low-molecular-weight heparin (nadroparin) on mortality in bedridden medical in-patients: a prospective randomised double-blind study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;61:347–351.

- Harenberg J, Roebruck P, Heene DL. Subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin versus standard heparin and the prevention of thromboembolism in medical inpatients: the heparin study in internal medicine group. Pathophysiol Haemos Thromb. 1996;26:127–139.

- Ishi SV, et al. Randomised controlled trial for efficacy of unfractionated heparin (UFH) versus low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) in thrombo-prophylaxis. J Assoc Phys India. 2013;61:882–886.

- Samama MM, Cohen AT, Darmon J-Y, et al. A comparison of enoxaparin with placebo for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in acutely ill medical patients: prophylaxis in medical patients with enoxaparin study group. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:793–800.

- Kleber F-X, Witt C, Vogel G, et al. Randomized comparison of enoxaparin with unfractionated heparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in medical patients with heart failure or severe respiratory disease. Am Heart J. 2003;145:614–621.

- Lechler E, Schramm W, Flosbach CW. The venous thrombotic risk in non-surgical patients: epidemiological data and efficacy/safety profile of a low-molecular-weight heparin (enoxaparin). The Prime Study Group. Pathophysiol Haemos Thromb. 1996;26:49–56.

- Lederle FA, Sacks JM, Fiore L, et al. The prophylaxis of medical patients for thromboembolism pilot study. Am J Med. 2006;119:54–59.

- Schellong SM, Haas S, Greinacher A, et al. An open-label comparison of the efficacy and safety of certoparin versus unfractionated heparin for the prevention of thromboembolic complications in acutely ill medical patients: CERTAIN. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11:2953–2961.

- Cohen AT, Davidson BL, Gallus AS, et al. Efficacy and safety of fondaparinux for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in older acute medical patients: randomised placebo controlled trial. BMJ. 2006;332:325–329.

- Riess H, Haas S, Tebbe U, et al. A randomized, double-blind study of certoparin vs. unfractionated heparin to prevent venous thromboembolic events in acutely ill, non-surgical patients: CERTIFY Study. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:1209–1215.

- Forette B, Wolmark Y. Calcium nadroparin in the prevention of thromboembolic disease in elderly subjects: Study of tolerance (translated by EMBASE). Presse Med. 1995;24:567–571.

- Kakkar AK, Cimminiello C, Goldhaber SZ, et al. Low-molecular-weight heparin and mortality in acutely ill medical patients. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2463–2472.

- Lanitis T, Leipold R, Hamilton M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of apixaban versus low molecular weight heparin/vitamin k antagonist for the treatment of venous thromboembolism and the prevention of recurrences. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:74.

- Pesavento R, Prandoni P. Prevention and treatment of the post-thrombotic syndrome and of the chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2015;13:193–207.

- Kelly J, Rudd A, Lewis RR, et al. Screening for subclinical deep-vein thrombosis. QJM. 2001;94:511–519.

- Dennis M, Mordi N, Graham C, et al. The timing, extent, progression and regression of deep vein thrombosis in immobile stroke patients: observational data from the CLOTS multicenter randomized trials. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:2193–2200.

- Vaitkus PT, Leizorovicz A, Cohen AT, et al. Mortality rates and risk factors for asymptomatic deep vein thrombosis in medical patients. Thromb Haemost. 2005;93:76–79.

- Christensen MC, Mayer S, Ferran J-M. Quality of life after intracerebral hemorrhage: results of the factor seven for acute hemorrhagic stroke (FAST) trial. Stroke. 2009;40:1677–1682.

- Hütter BO, Gilsbach JM, Kreitschmann I. Quality of life and cognitive deficits after subarachnoid haemorrhage. Br J Neurosurg. 1995;9:465–476.

- Shah A, Shewale A, Hayes CJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness of oral anticoagulants for ischemic stroke prophylaxis among nonvalvular atrial fibrillation patients. Stroke. 2016;47:1555–1561.