Abstract

Aims: To estimate healthcare resource utilization (HRU) and costs among patients with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) type 1 (SMA1) in real-world practice, overall and among patients treated with nusinersen. As a secondary objective, HRU and costs were estimated among patients with other SMA types (i.e. 2, 3, or 4 combined), overall and among patients treated with nusinersen.

Materials and methods: Patients with SMA were identified from the Symphony Health’s Integrated Dataverse (IDV) open claims database (September 1, 2016–August 31, 2018) and were classified into four cohorts based on SMA type and nusinersen treatment (i.e. SMA1, SMA1 nusinersen, other SMA, and other SMA nusinersen cohorts). The index date was the date of the first SMA diagnosis after December 23, 2016 or, for nusinersen cohorts, the date of nusinersen initiation. The study period spanned from the index date to the earlier among the end of clinical activity or data availability.

Results: Patients in the SMA1 (n = 349) and SMA1 nusinersen (n = 45) cohorts experienced an average of 59.4 and 56.6 days with medical visits per-patient-per-year (PPPY), respectively, including 14.1 and 4.6 inpatient days. Excluding nusinersen-related costs, total mean healthcare costs were $137,627 and $92,618 PPPY in the SMA1 and SMA1 nusinersen cohorts, respectively. Mean nusinersen-related costs were $191,909 per-patient-per-month (PPPM) for the first 3 months post-initiation (i.e. loading phase) and $36,882 PPPM thereafter (i.e. maintenance phase). HRU and costs were also substantial among patients in the other SMA (n = 5,728) and other SMA nusinersen (n = 404) cohorts, with an average of 44.5 and 63.7 days with medical visits PPPY and total mean healthcare costs (excluding nusinersen-related costs) of $49,175 and $76,371 PPPY, respectively.

Limitations: The database may contain inaccuracies or omissions in diagnoses, procedures, or costs, and does not capture medical services outside of the IDV network.

Conclusions: HRU and healthcare costs were substantial in patients with SMA, including in nusinersen-treated patients.

Introduction

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a severe neuromuscular disease characterized by the degeneration of alpha motor neurons in the spinal cord, resulting in progressive proximal muscle weakness and paralysisCitation1,Citation2. It is the leading genetic cause of infant mortality, affecting ∼1/10,000–1/11,000 live birthsCitation1,Citation2. The disease is caused by mutations in the survival motor neuron 1 gene (SMN1), which leads to loss of motor neurons with resulting muscular atrophy and subsequent impairment of motor neuron functionCitation2,Citation3. SMA is clinically classified into five phenotypes (SMA types 0–4) according to the age at disease onset and motor function achievedCitation1,Citation2. SMA type 0 is the most severe and is typically fatal in utero or shortly after birth. SMA type 1 (SMA1; also named Werdnig-Hoffmann disease) is the most common type, accounting for ∼50–60% of all SMA casesCitation2,Citation4. Infants with SMA1 usually have onset of clinical signs within the first 6 months of life, and fail to reach basic developmental motor milestones, such as the ability to sit without assistanceCitation4,Citation5. In the absence of external intervention, patients with SMA1 generally do not survive beyond the first 2 yearsCitation1,Citation6. SMA types 2, 3, and 4 are associated with progressively later disease onsets and are generally less severe and more stable in disease course, with minimal to no change in life expectancyCitation1,Citation2.

Although the genetic cause of SMA has been established for some time, there have been no effective treatments until recentlyCitation3,Citation6. Historically, the management of SMA relied on supportive care, including neuromuscular, respiratory, orthopedic, and nutritional support. While the collective implementation of these management strategies have had an unequivocal impact on survival, they do not attenuate the underlying neuromuscular declineCitation7,Citation8. On December 23, 2016, nusinersen became the first disease-modifying therapy approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of SMACitation9. This approval was based on the results from the phase III ENDEAR (nusinersen in infants with early-onset SMA)Citation6 and CHERISH (nusinersen in later-onset SMA) trialsCitation10, which demonstrated the impact of this treatment on the clinical outcomes of patients with SMA such as motor function and/or overall survival.

Assessments of the real-world economic burden of SMA, including the healthcare resource utilization (HRU) and healthcare costs associated with the disease, remain limited in the USCitation11–19. In a study conducted by Dabbous et al.Citation13, which evaluated the economic burden of patients with SMA1 in the US, healthcare costs in the first month following SMA diagnosis averaged $27,063 per patient compared to $274 among matched patients without SMA. Similarly, Goble et al.Citation14 conducted a retrospective analysis of pediatric and adult patients with SMA (any type) and reported mean healthcare costs of $65,490 PPPY. This figure was notably high in patients aged <2 years old, for whom it reached $159,227 PPPYCitation14. However, prior studies included data collected before the approval of nusinersen and, thus, did not capture the impact of this recent development on the disease burdenCitation11–19. Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to provide contemporary estimates of the HRU and healthcare costs among patients with SMA1 in real-world US practice, overall and following the initiation of nusinersen among treated patients. As a secondary objective, this study aimed to provide estimates of the HRU and healthcare costs among patients with SMA types other than 1 (i.e. types 2, 3, or 4 combined), overall and following the initiation of nusinersen among treated patients.

Methods

Data source

The Symphony Health’s Integrated Dataverse (IDV) open claims database was used to conduct this study, with data covering the period that spanned from September 1, 2016 to August 31, 2018. The IDV database is a longitudinal patient data source, which captures prescription claims, medical utilization, and costs across the US. This administrative claims database covers all payment types, including commercial plans, Medicare Part D, cash, assistance programs, and Medicaid. Data were de-identified and complied with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Therefore, no reviews by an institutional review board were required.

Study design and study population

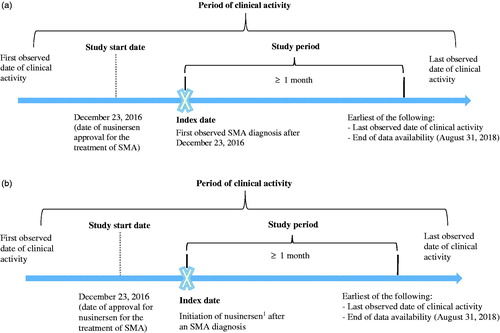

A retrospective cohort study design () was used to assess the HRU and healthcare costs of patients with SMA. Patients were classified into four non-mutually exclusive study cohorts based on their SMA type and nusinersen treatment status. Patients aged <2 years as of their first observed SMA diagnosis and who had no procedure codes for braces, walker, or wheelchair were considered to have SMA1 and were, thus, included in the SMA1 cohort. Patients with SMA1 treated with nusinersen were further included in the SMA1 nusinersen cohort. For the secondary analyses, patients with SMA types other than 1 (i.e. types 2, 3, or 4) were included in the other SMA cohort and those treated with nusinersen were further included in the other SMA nusinersen cohort. Patients aged 21 years or above as of their first SMA diagnosis who underwent gastrostomy were considered as non 5q-SMA and were further excluded from the other SMA cohorts.

Figure 1. Study design (a) SMA1 and other SMA cohorts; (b) SMA1 nusinersen and other SMA nusinersen cohorts. Abbreviations. SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; SMA1, spinal muscular atrophy, type 1. 1The initiation of nusinersen was identified based on the first indicator for treatment with nusinersen.

The study start date was defined as December 23, 2016 (i.e. the date when nusinersen was approved for the treatment of SMA in pediatric and adult patients). The index date was defined as the date of the first observed SMA diagnosis after December 23, 2016 or, for the nusinersen-treated cohorts, as the date of initiation of nusinersen. The study period spanned from the index date to the earlier among the last observed date of clinical activity or end of data availability (i.e. August 31, 2018).

Sample selection

Patients were included in the study if they met the following criteria: had ≥1 SMA diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM] codes: G12.0, G12.1, G12.8, G12.9) recorded on or after the study start date; and were observed for ≥1 month after their first SMA diagnosis after the study start date. Since patients were not further selected based on survival status, the final sample intended to include a combination of patients who may have survived or died after the first month of observation. In addition, for patients that were not treated with nusinersen, other criteria were applied to reduce the likelihood of including patients with rule-out diagnoses and/or genetic testing during pregnancy: ≥2 SMA diagnoses at any time, and no pregnancy-related diagnoses (ICD-10-CM codes: Z33.x, Z34.x, Z36.x, Z37.x, Z3A, A34.x, O00.x-O9A.x) at any time.

Furthermore, patients treated with nusinersen (i.e. SMA1 nusinersen and other SMA nusinersen cohorts) were required to be initiated on nusinersen after an SMA diagnosis, with the initiation date after December 23, 2016, and to be observed for ≥1 month after nusinersen initiation.

Identification of treatment with nusinersen

Treatment with nusinersen was identified based on the records of one of the following codes: ≥1 nusinersen-specific Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) code (i.e. C9489 as of June 17, 2017; J2326 as of December 16, 2017) or ≥1 nusinersen-specific drug code (National Drug Code 64406-058-01 and 71860-396-01). Since the HCPCS codes associated with nusinersen were introduced only several months after its approval, treatment with nusinersen prior to the availability of the nusinersen-specific codes was identified based on the following algorithm: ≥1 HCPCS code for unclassified drug or biologic treatment (C9399, J3490, J3590) along with an SMA diagnosis on the same claim as the procedure and a charged amount of ≥$90,000 for the procedure.

Study outcomes

Study outcomes were measured during the study period and included disease profile, HRU, and healthcare costs. Disease profile characteristics included SMA-related comorbidities and SMA-related services (i.e. mechanical ventilation support, nutritional support, physical/occupational therapy or rehabilitation, speech therapy, sleep studies, orthopedic surgeries, acupuncture, osteopathic services, and chiropractic services)Citation13.

HRU included inpatient (IP) stays (i.e. number of IP days), outpatient (OP) visits (i.e. office and clinic visits), and other visits (e.g. laboratory encounters, home health encounters, specialized treatment centers). In addition, medical visits with SMA-related events were also reported separately, overall (any setting) and during IP stays. SMA-related events were identified based on adverse events that occurred in ≥20% of patients in either treatment arm of nusinersen pivotal trialsCitation6,Citation10.

Healthcare costs were reported per-patient-per-year (PPPY) and inflated to 2018 US dollars using the medical care portion of the consumer price index. Total healthcare costs were evaluated and stratified into medical service costs (reported as charged amounts for the procedures) and pharmacy costs (reported as final paid amounts). Medical service costs were further stratified into IP, OP, and other visit costs. For IP stays, facility costs were imputed using hospital adjusted expenses per IP day for each US state reported by the Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation, the patient’s US state, and the length of the IP stayCitation20.

In addition, costs associated with SMA-related services (defined above), costs associated with SMA-related events (overall and during IP stays), and monthly nusinersen-related costs in the first year of treatment (calculated separately for the loading phase [i.e. months 1–3] and maintenance phase [i.e. months 4–12]) were also evaluated. Nusinersen-related costs included the costs of the drug and any other procedures recorded on the same claim (e.g. administration/injection, anesthesia).

Statistical analyses

Patient characteristics and study outcomes were summarized using descriptive statistics. Mean, standard deviation, and median were presented for continuous variables. Frequency counts and proportions were presented for categorical variables.

For HRU, incidence rates PPPY were calculated as the number of events divided by patient-years of observation. No statistical comparisons between cohorts were conducted.

Sensitivity analyses

Analyses were replicated among patients with newly diagnosed SMA as of their first observed SMA diagnosis after December 23, 2016. The date of the first recorded SMA diagnosis in the database was considered as the date of the first SMA diagnosis. For patients aged ≥2 years, a 6-month washout period was implemented to increase the likelihood that patients were newly-diagnosed as of their first recorded SMA diagnosis (i.e. a period of ≥6 months was required between the first month of clinical activity and the first observed SMA diagnosis; otherwise the date of the first SMA diagnosis was considered as unknown, and the patient was not considered newly-diagnosed).

Results

Baseline characteristics and disease profile among patients with SMA type 1

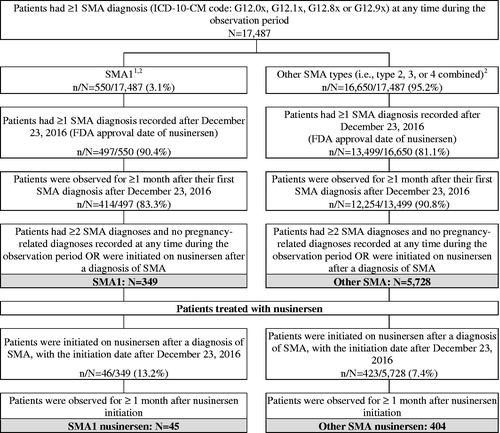

A total of 349 patients with SMA1 and 45 patients with SMA1 treated with nusinersen were included in the study (). On average, patients in the SMA1 cohort were aged 9.2 months and 55.6% were female; on average, patients in the SMA1 nusinersen cohort were aged 12.2 months and 62.2% were female (). The majority of patients in the SMA1 cohort were commercially insured (74.2%); this proportion reached 88.9% for patients in the SMA1 nusinersen cohort (). Patients in the SMA1 and SMA1 nusinersen cohorts were observed for an average of 9.7 months and 8.3 months, respectively (). In the SMA1 cohort, dyspnea and respiratory anomalies (42.1%), feeding difficulties and mismanagement (33.2%), and acute respiratory failure (32.4%) were the most common SMA-related comorbidities observed in the study period (). In the SMA1 nusinersen cohort, dyspnea and respiratory anomalies (44.4%), feeding difficulties and mismanagement (42.2%), and dysphagia (42.2%) were the most common comorbidities observed (). With regards to SMA-related services, mechanical ventilation support (46.4% and 42.2%), nutritional support (46.1% and 57.8%), and physical and/or occupational therapy/rehabilitation (22.6% and 42.2%) were the most commonly observed in the SMA1 cohort and SMA1 nusinersen cohort, respectively ().

Figure 2. Sample selection. Abbreviations. FDA, Food and Drug Administration; HCPCS, Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System; ICD-10-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification; SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; SMA1, spinal muscular atrophy type 1. 1Patients were considered to have SMA1 if there were aged <2 years as of their first observed SMA diagnosis and had no procedure codes for braces, walker, or wheelchair. 2Of note, 287 patients (1.6%) patients aged 21 years or above as of their first SMA diagnosis who underwent gastrostomy were considered as non 5q SMA and were further excluded from the study.

Table 1. Characteristics and disease profile of patients with SMA1.

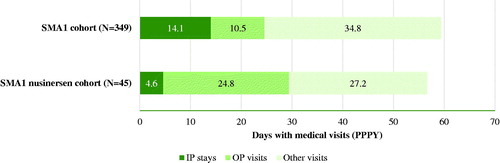

HRU among patients with SMA type 1

During the study period, 39.3% and 42.2% of patients in the SMA1 cohort and SMA1 nusinersen cohort had ≥1 IP stay, with an average of 1.9 and 1.7 admissions PPPY, respectively. Patients in the SMA1 and SMA1 nusinersen cohorts experienced an average of 59.4 and 56.6 days with medical visits PPPY in any setting, respectively, with IP visits accounting for 14.1 and 4.6 days PPPY (). On average, 22.9 and 18.5 days with medical visits for SMA-related events were observed PPPY in the SMA1 and SMA1 nusinersen cohorts, respectively. Of these, 8.8 days PPPY occurred in the IP setting for the SMA1 cohort, and 3.4 days PPPY in the SMA1 nusinersen cohort (). For both cohorts, respiratory failure was the SMA-related event associated with the highest incidence of medical visits PPPY, both overall (SMA1: 13.4 days, SMA1 nusinersen: 11.4 days) and in the IP setting (SMA1: 6.6 days, SMA1 nusinersen: 2.5 days; ).

Figure 3. HRU among patients with SMA1. Abbreviations. HRU, healthcare resource utilization; IP, inpatient; OP, outpatient; PPPY, per patient per year; SMA1, spinal muscular atrophy type 1.

Table 2. HRU and healthcare costs associated with SMA-related events for patients with SMA1.

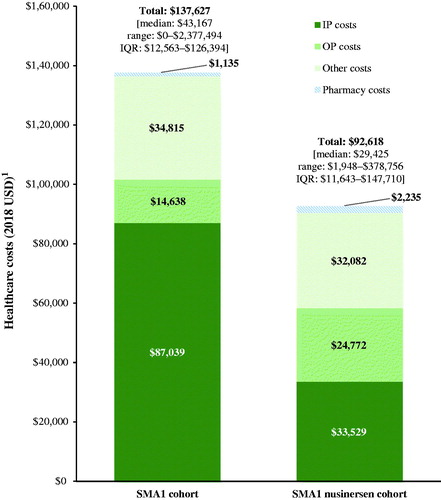

Healthcare costs among patients with SMA type 1

Excluding nusinersen-related costs, total mean healthcare costs were $137,627 (median = $43,167) PPPY in the SMA1 cohort and $92,618 (median = $29,425) PPPY in the SMA1 nusinersen cohort (). Costs for IP, OP, and other visits accounted for 63.2%, 10.6%, and 25.3% of total healthcare costs in the SMA1 cohort, respectively. In the SMA1 nusinersen cohort, these proportions were 36.2%, 26.7%, and 34.6%, respectively.

Figure 4. Healthcare costs (excluding nusinersen-related costs) among patients with SMA1. Abbreviations. IP, inpatient; IQR, interquartile range; OP, outpatient; SMA1, spinal muscular atrophy type 1; USD, United States dollars. 1Costs for procedures recorded on the same claim as a nusinersen injection were excluded.

On average, charged costs associated with SMA-related services (excluding facility costs for IP stays, as these cannot be imputed to a specific service) were $10,656 (median = $640) PPPY in the SMA1 cohort and $13,821 (median = $3,140) PPPY in the SMA1 nusinersen cohort. Furthermore, charged costs associated with SMA-related events reached on average $63,800 (median = $8,822) PPPY for patients in the SMA1 cohort (46.4% of the total healthcare costs, excluding nusinersen-related costs), and $46,723 (median = $7,367) PPPY for those in the SMA1 nusinersen cohort (50.4% of total healthcare costs, excluding nusinersen-related costs) (). For both the SMA1 and SMA1 nusinersen cohorts, respiratory failure was the SMA-related event associated with the highest charged costs on average (SMA1 = $45,518, SMA1 nusinersen = $31,461 PPPY). In the SMA1 nusinersen cohort, mean nusinersen-related costs were $191,909 (median = $144,487) per patient per month (PPPM) for the first 3 months post-initiation (i.e. loading phase) and $36,882 (median = $16,132) PPPM for months 4–12 (i.e. maintenance phase). This would translate into a mean cost per-patient of $907,665 (median = $578,649) in the first year following treatment initiation.

Secondary analyses—patients with other SMA types (i.e. types 2, 3, or 4 combined)

A total of 5,728 patients with other types of SMA and 404 patients with other types of SMA treated with nusinersen were included in the secondary analyses (). On average, patients in the other SMA cohort were aged 30.9 years and 47.5% were female; on average, patients in the other SMA nusinersen cohort were aged 14.8 years and 51.2% were female (Supplementary Table S1).

Over an average study period of 14.0 months for patients in the other SMA cohort and 9.1 months for patients in the other SMA nusinersen cohort, 21.8% and 16.6% of patients had ≥1 IP stay, with an average of 0.4 and 0.5 admissions PPPY, respectively. Patients in the other SMA and other SMA nusinersen cohorts experienced an average of 44.5 and 63.7 days with medical visits PPPY in any setting, respectively, with IP visits accounting for 1.9 and 2.5 days (Supplementary Figure S1). Excluding nusinersen-related costs, total mean healthcare costs were $49,175 (median = $18,089) PPPY in the other SMA cohort and $76,371 (median = $23,649) PPPY in the other SMA nusinersen cohort, and were mainly driven by costs other than those incurred in the IP and OP settings (54.8% and 55.8% for the other SMA and other SMA nusinersen cohorts, respectively, Supplementary Figure S2). For both the other SMA and other SMA nusinersen cohorts, respiratory failure was the SMA-related event associated with the highest charged costs on average (other SMA: $7,207 PPPY, other SMA nusinersen: $13,381 PPPY; Supplementary Table S2). In the other SMA nusinersen cohort, mean nusinersen-related costs were $223,189 (median = $166,587) PPPM for the first 3 months post-initiation (i.e. loading phase) and $40,347 (median = $33,710) PPPM for months 4–12 (maintenance phase). This would translate into a mean cost per-patient of $1,032,690 (median = $803,151) in the first year following treatment initiation.

Sensitivity analyses

Patients newly-diagnosed with SMA1 (n = 276) had an average of 57.1 days with medical visits PPPY (including 17.0 IP days) and incurred average total healthcare costs (excluding nusinersen-related costs) of $147,146 (median = $42,049) PPPY; those treated with nusinersen (n = 34) had an average of 62.5 days with medical visits PPPY (including 5.7 IP days) and incurred average total healthcare costs (excluding nusinersen-related costs) of $99,067 (median = $54,969) PPPY. Patients newly-diagnosed with other SMA types (n = 1,721) had an average of 34.0 days with medical visits PPPY and incurred average total healthcare costs (excluding nusinersen-related costs) of $43,234 (median = $15,791) PPPY; those treated with nusinersen (n = 80) had an average of 33.4 days with medical visits PPPY, and incurred average total healthcare costs (excluding nusinersen-related costs) of $36,877 (median = $6,109) PPPY.

Discussion

This retrospective cohort study assessed HRU and healthcare costs among patients with SMA in real-world US practice, overall and following the initiation of nusinersen among treated patients. Our results indicated that patients with SMA1 had almost 60 days with medical visits PPPY, with about a quarter of these occurring in the IP setting. Average annual healthcare costs (excluding nusinersen-related costs) were substantial in patients with SMA1, including in those treated with nusinersen. Similarly, HRU and healthcare costs were high in patients with other SMA types, including in those who received treatment.

In accordance with findings from the current study, previous studies have consistently found SMA to be associated with high HRU and healthcare costsCitation11–19, including a few recent claims-based studies that evaluated the economic burden of SMACitation12–14. For example, Dabbous et al.Citation13 conducted a retrospective analysis of patients with SMA1 using the Quintiles IMS’s PharMetrics Plus Health Plan Claims Database (February 2011–November 2016). The authors found that healthcare costs in the first month following SMA diagnosis averaged $27,063 per patient, while it was only $274 in matched patients without SMACitation13. These costs are higher than those found in the present study. Given that the observation period in the previous study was limited to a 1-month period following the first SMA diagnosis, this discrepancy could potentially be explained by non-linear costs over time and/or an increase in HRU around the first SMA diagnosis (e.g. diagnostic work-up or initiation of supportive care). Indeed, in our sensitivity analyses, patients newly-diagnosed with SMA1 incurred numerically higher healthcare costs compared with all patients with SMA1 ($147,146 and $137,627 PPPY, respectively), emphasizing potential non-linearity in healthcare spending and the dynamic disease burden of SMA. While differences in disease duration and observation periods make comparisons between studies difficult, both studies highlight the significant HRU and costs associated with SMA1. In another study, Goble et al.Citation14 retrospectively analyzed HRU and costs in pediatric and adult patients with SMA using data from the MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Supplemental (January 2012–March 2017). Similar to our study, the authors reported high HRU and healthcare costs among patients with SMA. More specifically, patients aged <2 years (i.e. who likely had SMA1) had particularly high healthcare costs that amounted to $159,227 PPPY, those aged 2–18 years had PPPY costs of $105,206, and those aged >18 years had PPPY costs of $39,355. Similarly, Armstrong et al.Citation12 conducted a retrospective analysis of pediatric patients (<18 years) with SMA using US Department of Defense Military Healthcare System (MHS) data contained within the MHS Data Repository (2003–2012). The authors reported that PPPY healthcare costs were significantly higher for patients diagnosed in their first year of life (i.e. >$110,000) compared to those diagnosed after the first year (i.e. >$30,000). Assuming that patients diagnosed in the first year of life mostly represented patients with SMA1, these results are also aligned with the high healthcare costs observed in the current study. Finally, a retrospective cohort analysis of IP admissions of children with SMA reported mean annualized hospitalization costs per patient of $104,197Citation19. While slightly higher than the IP costs in the SMA1 cohort of the current study ($87,039 PPPY), the discrepancy may be explained by differences in treatment availability (i.e. nusinersen) and patient population, including differences in severity of SMA.

In contrast to prior US studies, which were based on data prior to the FDA approval of nusinersen, our study evaluated HRU and costs of patients with SMA specifically in the era following the landmark FDA approval of nusinersen. In particular, as the treatment landscape continues to evolve, changes in clinical decision-making may affect resulting healthcare costs. Our findings indicate that, despite the recent availability of a disease-modifying treatment, the economic burden of SMA remains considerable. The substantial HRU and costs observed among treated patients may be partially explained by additional monitoring, prompting the use of more healthcare resources. Moreover, treated patients may have had a more severe disease profile prior to treatment or may have been more likely to seek support and use healthcare resources. In particular, a numerically higher percentage of treated patients were commercially-insured compared to the overall SMA population (88.9% vs 74.2%, respectively, among patients with SMA1, and 85.4% vs 69.4% among patients with other SMA types), suggesting that treated patients may have had greater access to medical coverage, which could have affected HRU. Finally, while treatment with nusinersen improves motor functionCitation6,Citation10, symptoms requiring medical management may persist after treatmentCitation21,Citation22. For example, in the current study, SMA-related events were associated with about one-third of all days with medical visits among patients treated with nusinersen with SMA1, mostly driven by respiratory failure. Costly invasive procedures like tracheostomy are commonly used to manage respiratory failure, but changing treatment paradigms leading to the use of less invasive procedures have the potential to reduce costs and increase life expectancy in these patientsCitation23.

Nonetheless, our results suggest that disease severity is reduced in patients treated with nusinersen. Indeed, while the percentage of patients with ≥1 IP stay appeared numerically similar between the SMA1 (39.3%) and SMA1 nusinersen cohorts (42.2%), the average number of IP days PPPY was numerically lower in the latter cohort (SMA1: 14.1 days, SMA1 nusinersen: 4.6 days). Furthermore, the numerically higher incidence of OP visits among patients in the SMA1 nusinersen compared with those in the SMA1 cohort may indicate that events previously requiring an IP stay may now be managed in an OP setting, which is also consistent with a reduced disease severity among patients treated with nusinersen.

Overall, results from the present study suggest that treatments with the potential to further alleviate symptoms could significantly reduce the burden of disease. Of note, onasemnogene abeparvovec-xioi was recently approved by the FDA on May 24, 2019 for the treatment of SMACitation24. Given that the data period covered in the current study spanned only until August 2018, it was not possible to evaluate the impact of this newly-approved treatment in this study. Further research is required to assess the impact of treatment with onasemnogene abeparvovec-xioi on the economic burden of SMA. Clinical trials are also underway to investigate new treatments for SMA, which could improve the outlook for patientsCitation21,Citation25. Lastly, the increasing implementation of statewide SMA newborn screening programs may have additional effects on disease burden, enabling earlier detection that allows for more rapid and effective treatment, thus potentially increasing the benefits of therapeutic managementCitation4,Citation26.

Limitations

This study should be interpreted in the context of some limitations. Since the study was conducted in the US, the results may not be generalizable to patients in other countries, as there may be differences in patient characteristics, treatment practices, and healthcare systems across countries. Similarly, due to the low proportion of Medicaid-insured patients included, the results may not be representative of all Medicaid-insured patients in the US, nor the real-world proportion of Medicaid-insured patients receiving care for SMA. It should also be noted that the algorithm used to classify SMA1 was based on a first SMA1 diagnosis observed under the age of 2; since SMA type 2 has an overlapping age of onset, the SMA1 cohorts may have included some patients with SMA type 2 as well, especially if there are delays in obtaining equipment such as braces, walker, or wheelchair. In addition, the sample size of the SMA1 nusinersen cohort (n = 45) was relatively small, making it more sensitive to outliers. However, the range of observed costs for this cohort does not suggest that total healthcare costs (excluding nusinersen-related costs) were driven by a few outliers. Moreover, all patients observed for ≥1 month following the initiation of nusinersen treatment were included in this cohort, and no other exclusion factors were applied, reducing the chance of bias. A limitation must also be acknowledged with regards to the grouping of SMA types 2, 3, and 4 into a single cohort as part of the secondary analyses. While this analysis provided a global overview of the disease burden for SMA types other than 1, it overlooked important distinctions between sub-types. For example, in a post-hoc analysis identifying SMA type based on current age, age at first observed diagnosis, and procedures, there were important differences observed in healthcare costs across types; mean total healthcare costs (excluding nusinersen-related costs) were $82,799 PPPY (median = $38,922) for patients with SMA type 2, $54,923 PPPY (median = $23,066) for those with SMA type 3, and $34,451 PPPY (median = $11,972) for SMA type 4.

As with all claims databases, Symphony Health’s IDV may contain inaccuracies or omissions in diagnoses, procedures, or costs. It should also be noted that medical service costs were reported as charged amounts, which may differ from paid amounts. In addition, the database does not report facility costs that may be associated with medical procedures. Accordingly, facility costs have been imputed based on average costs per IP day reported in publications, but they may not be representative of the facility costs incurred specifically by patients with SMA. Moreover, Symphony Health’s IDV database does not capture service claims from providers outside of the IDV network; therefore, costs may have been under-estimated for patients seeking care outside the network. Moreover, the IDV data is a claims-based database; therefore, no information was available on mortality, quality-of-life, nor disease severity, including relevant clinical outcomes such as the Hammersmith scale. Accordingly, outcomes reported here represent a partial assessment of the disease burden, based on HRU and direct healthcare costs and did not include other direct non-healthcare costs and indirect costs incurred by the patients and their caregivers, such as those associated with absenteeism, temporary housing, or transportation, as well as the impact of SMA on quality-of-life for patients and caregivers. Consequently, the economic burden associated with SMA is likely higher than that estimated here.

Finally, patients were observed over a limited study period; to the extent that costs and HRU may not be constant over time, this may lead to an under-estimation or over-estimation of the costs and HRU. For example, if costs and HRU increase as the disease progresses, it is likely that these would be under-estimated if assessed over a short period of time. Alternatively, if costs and HRU around the index date are expected to be higher than at a later point, these could be over-estimated. This scenario could occur if, for instance, the risk of adverse events is higher within the first few months following nusinersen initiation, or if there is a delay in physiologic response to treatment. Accordingly, future studies with a longer follow-up are warranted to capture long-term trends in the economic burden associated with SMA1.

Conclusions

In this real-world contemporary analysis of patients with SMA, HRU and healthcare costs were substantial, including in nusinersen-treated patients. With the recent changes in the treatment landscape, further research is warranted to assess the impact of newer treatments on the economic burden of SMA and whether these treatments have the potential to further alleviate the cost burden of this debilitating disease.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by AveXis, Inc., a Novartis company. The study sponsor was involved in several aspects of the research, including the study design, the interpretation of data, the writing of the manuscript, and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Declaration of financial/other interests

M.D., O.D., R.A., and D.S. are employees of AveXis, Inc., and may own stocks or stock options. M.G.L. and M.C. are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., which provided paid consulting services to AveXis, Inc. for the conduct of the present study. The peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work. In addition, a reviewer on this manuscript discloses participating as a principal investigator for SMA clinical trials sponsored by Biogen, AveXis, and Roche, and receiving personal compensation from Biogen, Roche, and AveXis for consultancy. The reviewers have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Previous presentations

Part of the material in this manuscript was presented at ISPOR 2019, held May 18–22 in New Orleans, LA.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (146.4 KB)Acknowledgements

Medical writing assistance was provided by Christine Tam and Samuel Rochette, who are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., which provided consulting services to AveXis, Inc. to conduct the present study. The authors thank Sherry Shi and Mikhail Davidson for their analytical support and Eric Q. Wu and Annie Guérin for consulting support.

References

- Groen EJN, Talbot K, Gillingwater TH. Advances in therapy for spinal muscular atrophy: promises and challenges. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14:214–224.

- Waldrop MA, Kolb SJ. Current Treatment Options in Neurology-SMA therapeutics. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2019;21:25.

- Sumner CJ, Crawford TO. Two breakthrough gene-targeted treatments for spinal muscular atrophy: challenges remain. J Clin Invest. 2018;128:3219–3227.

- Glascock J, Sampson J, Haidet-Phillips A, et al. Treatment algorithm for infants diagnosed with spinal muscular atrophy through newborn screening. JND. 2018;5:145–158.

- Markowitz JA, Singh P, Darras BT. Spinal muscular atrophy: a clinical and research update. Pediatr Neurol. 2012;46:1–12.

- Finkel RS, Mercuri E, Darras BT, et al. Nusinersen versus Sham Control in Infantile-Onset Spinal Muscular Atrophy. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1723–1732.

- Finkel RS, Mercuri E, Meyer OH, et al. Diagnosis and management of spinal muscular atrophy: Part 2: Pulmonary and acute care; medications, supplements and immunizations; other organ systems; and ethics. Neuromuscular Disord. 2018;28:197–207.

- Mercuri E, Finkel RS, Muntoni F, et al. Diagnosis and management of spinal muscular atrophy: Part 1: Recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, orthopedic and nutritional care. Neuromuscular Disord. 2018;28:103–115.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves first drug for spinal muscular atrophy. 2016. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm534611.htm

- Mercuri E, Darras BT, Chiriboga CA, et al. Nusinersen versus Sham Control in Later-Onset Spinal Muscular Atrophy. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:625–635.

- Cardenas J, Menier M, Heitzer MD, et al. High Healthcare Resource Use in Hospitalized Patients with a Diagnosis of Spinal Muscular Atrophy Type 1 (SMA1): retrospective analysis of the Kids' Inpatient Database (KID). Pharmacoecon Open. 2018;3:205–213.

- Armstrong EP, Malone DC, Yeh WS, et al. The economic burden of spinal muscular atrophy. J Med Econ. 2016;19:822–826.

- Dabbous O, Seda J, Sproule D, editors. Economic burden of infantile-onset (type 1) spinal muscular atrophy: A retrospective claims database analysis. ISPOR 2018 (poster); Baltimore, MD: AveXis, Inc. 2018.

- Goble J, Dai D, Boulos F, et al. The economic burden of spinal muscular atrophy patients in a commercially-insured population in the United States. Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMCP) Nexus 2018 (poster); Orlando, FL: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

- Teynor M, Hou Q, Zhou J, et al. Healthcare resource use in patients with diagnosis of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) in OptumTM US Claims Database. Neurology. 2017;88. Available at: https://n.neurology.org/content/88/16_Supplement/P4.158?rss=1

- Teynor M, Zhou J, Hou Q, et al. Retrospective analysis of healthcare resource utilization (HRU) in patients with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) in MarketScan®. Neurology. 2017;88. Available at: https://n.neurology.org/content/88/16_Supplement/P3.186

- Klug C, Schreiber-Katz O, Thiele S, et al. Disease burden of spinal muscular atrophy in Germany. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2016;11:58.

- López-Bastida J, Peña-Longobardo LM, Aranda-Reneo I, et al. Social/economic costs and health-related quality of life in patients with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) in Spain. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12:141–147.

- Lee M, Jr., Franca UL, Graham RJ, et al. Pre-Nusinersen hospitalization costs of children with spinal muscular atrophy. Pediatr Neurol. 2018;92:3–5.

- Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. Hospital Adjusted Expenses per Inpatient Day 2018 [cited 2019 Jan 17]. Available at: https://www.kff.org/health-costs/state-indicator/expenses-per-inpatient-day

- Corey DR. Nusinersen, an antisense oligonucleotide drug for spinal muscular atrophy. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:497–499.

- Prasad V. Nusinersen for spinal muscular atrophy: Are We Paying Too Much for Too Little? JAMA Pediat. 2018;172:123–125.

- Bach J, Gupta K, Reyna M, et al. Spinal muscular atrophy type 1: prolongation of survival by noninvasive respiratory aids. Pediat Arthma, Allerg, Imm. 2009;22:151–161.

- Novartis AG. AveXis receives FDA approval for Zolgensma®, the first and only gene therapy for pediatric patients with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) 2019 [cited 2019 Jun 25]. Available at: https://www.novartis.com/news/media-releases/avexis-receives-fda-approval-zolgensma-first-and-only-gene-therapy-pediatric-patients-spinal-muscular-atrophy-sma

- Cure SMA. Trials currently recruiting: Cure SMA; 2019 [cited 2019 Jan 9]. Available at: http://www.curesma.org/research/our-strategy/clinical-trials/trials-currently-recruiting/

- Kraszewski JN, Kay DM, Stevens CF, et al. Pilot study of population-based newborn screening for spinal muscular atrophy in New York state. Genet Med. 2018;20:608–613.