Abstract

Aims: To estimate the long-term budget impact of expanding Medicare coverage of anti-obesity interventions among adults aged 65 and older in the US.

Materials and methods: This study analyzed a representative sample of Medicare beneficiaries from the combined 2008–2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Population characteristics, cost and effectiveness of anti-obesity interventions, and the sustainability of weight loss in real-life were modeled to project the budgetary impact on gross Medicare outlay over 10 years. Hypothetical scenarios of 50% and 67% increases in intervention participation above base case were used to model moderate and extensive Medicare coverage expansion of intensive behavior therapy and pharmacotherapy.

Results: For each Medicare beneficiary receiving anti-obesity treatment, we estimate Medicare savings of $6,842 and $7,155 over 10 years under moderate and extensive coverage utilization assumptions, respectively. The average cost of intervention is $1,798 and $1,886 per treated participant. Taking the entire Medicare population (treated and untreated) into consideration, the estimated 10-year budget savings per beneficiary are $308 and $339 under moderate and extensive assumptions, respectively. Sensitivity analysis of drug adherence rate and weight-loss efficacy indicated a potential variation of budget savings within 7% and 22% of the base case, respectively. Most of the projected cost savings come from lower utilization of ambulatory services and prescription drugs.

Limitations: Due to the scarcity of studies on the efficacy of pharmacotherapy among older adults with obesity, the simulated weight loss and long-term maintenance effects were derived from clinical trial outcomes, in which older adults were mostly excluded from participation. The model did not include potential side-effects from anti-obesity medications and associated costs.

Conclusions: This analysis suggests that expanding coverage of anti-obesity interventions to eligible individuals could generate $20–$23 billion budgetary savings to Medicare over 10 years.

Introduction

Obesity is widely acknowledged as a critical public health concern in the US, and is the subject of numerous studies linking it to elevated risk of chronic disease and increased healthcare expendituresCitation1–3. The estimated economic burden of obesity and obesity-related treatment was $427.8 billion in 2014, an amount that has undoubtedly escalated in subsequent years alongside the rising number of people with obesityCitation4.

The US population aged 65 and older is projected to increase from 49 million in 2016 to 73 million by 2030, and high rates of obesity among older adults portend rising prevalence of obesity-related chronic diseases and Medicare expendituresCitation5. Obesity rates have reached 37.5% and 39.4% among men and women aged 60 and older, respectively, compared to less than 35% from year 2000 and earlierCitation6. Given obesity’s substantial impact, policies that seek to treat and prevent obesity are of high priority and warrant careful consideration. Lifestyle interventions that promote physical activity and healthy diet, as well as anti-obesity medications, have proven effective in weight managementCitation7–14. Since 2012, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved four prescription weight-loss medications for long-term use—lorcaserin, phentermine-topiramate, liraglutide, and naltrexone/bupropionCitation15. Other weight-loss drugs that curb appetite, e.g. phentermine and benzenediamine, are approved only for short-term useCitation16.

In 2012, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services initiated coverage for Intensive Behavioral Therapy (IBT) for Medicare beneficiaries with a body mass index (BMI) >30 kg/mCitation2,Citation17. However, only 0.5% of beneficiaries with obesity use this serviceCitation18. Pharmacotherapy is not yet covered by Medicare, although several legislative and regulatory proposals to cover FDA-approved anti-obesity medications for eligible Medicare beneficiaries have been put forward. One proposal is the Treat and Reduce Obesity Act (TROA), which seeks to expand existing coverage of IBT and allow Medicare Part D to cover prescription anti-obesity medicationsCitation19.

In 2015, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) discussed potential budgetary implications of policies targeting obesityCitation18. CBO highlighted the paucity of studies assessing policy implications of clinical outcomes and overall healthcare spending for Medicare beneficiaries, asking: How many beneficiaries would participate in treatment for obesity? What share of participants would complete the full course of treatment? What would be the direct costs of treatment? How much weight would participants lose, and how long would that weight loss be maintained? How would weight loss affect the healthcare spending of participants and the federal budget? To help address these questions and fill the research gap of the financial effects of proposed anti-obesity coverage policies, this study used a validated, peer-reviewed microsimulation model to project the 10-year budget impact of expanding Medicare’s coverage of anti-obesity interventions.

Methods

Model framework

This study used a simulation model, informed and supported by a comprehensive literature review, to project change in Medicare spending over a 10-year period under different coverage scenarios regarding anti-obesity treatments. The microsimulation modeled changes in health outcomes and expected healthcare expenditures over time for each person in a representative sample of Medicare beneficiaries with obesity. Model data sources, methods, assumptions, limitations, and validation activities are summarized below; more details have been published elsewhereCitation10,Citation20,Citation21.

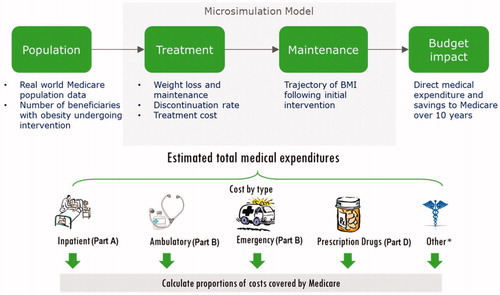

The simulation starts with a representative sample of Medicare beneficiaries derived from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) to model real life population characteristics (). Model inputs include: cost and effectiveness of anti-obesity interventions, duration of weight loss and maintenance, annual probability of disease onset and change in clinical outcomes, annual medical costs, and other information (e.g. annual mortality probabilities) to produce the estimated budgetary impact on Medicare over 10 years. The model simulates Medicare expenditures across five categories—inpatient, ambulatory, emergency department, prescription medication, and “other”—after accounting for patient out-of-pocket contributions (deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance).

Population

From the combined 2008–2016 NHANES files (n = 19,227 adults), we identified 2,375 adults aged 65 or older with anti-obesity intervention eligibility criteria of BMI ≥30, or BMI ≥27 with at least one of the following complications: hypertension, dyslipidemia, or type-2 diabetes. The profile of each individual modeled consists of demographics (age, sex, race, Hispanic ethnicity); biometric parameters (BMI, systolic [SBP] and diastolic [DBP] blood pressure, total and high-density [HDL] lipoprotein cholesterol, and hemoglobin A1c levels); current smoking status; and presence of select chronic conditions linked to obesity, including diabetes, hypertension, congestive heart failure, ischemic heart disease, stroke, sleep apnea, depression, and various cancersCitation22. Using the sample weights and random sampling with replacement, we constructed an analytic file of 50,000 people, representative of non-institutionalized Medicare beneficiaries meeting intervention eligibility.

Microsimulation

The previously published Markov-based model simulates yearly progression of each person’s health status and onset of more than 50 disease conditions based on each individual’s profileCitation10,Citation20,Citation21,Citation23. Prediction equations used to model change in health status originated from published clinical trials, observational studies and meta-analyses, and original analysis of public databases. Body weight is a key model input, and reduction in body weight directly improves or lowers risk for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, depression, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, osteoarthritis, and 16 cancer types. Reduced body weight indirectly decreases onset probability of other modeled health conditions (stroke, myocardial infarction, renal failure, and atrial fibrillation) via improvement in blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood glucose levelsCitation21.

Prediction equations for annual medical expenditures were estimated using a set of generalized linear models with gamma distribution and log link derived from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS, 2010–2016), with predictors including patient demographics (age, sex, race, ethnicity); body weight (BMI); presence of diabetes, hypertension, congestive heart failure, ischemic heart disease, retinopathy, and end-stage renal disease; and history of myocardial infarction, stroke, and various cancers. We used a zero-inflated log-ratio regression to model the allocation of total medical expenditures across the five cost categories modeledCitation20. There are two components from the regression outcome: estimated logistic regressions to model the probability that an individual incurred expenditure in that category, and the log-transformed ratio of expenditures in each category using the generalized linear model. Combining the information from both components allowed us to calculate the expected impact of weight-loss intervention on Medicare spending associated with Part A (inpatient), Part B (emergency and ambulatory), and Part D (prescription drug), as well as total spending.

Weight loss and maintenance

The model simulated weight loss under two treatment approaches: IBT alone, and IBT combined with anti-obesity medication. IBT treatment is implemented by healthcare providers offering high-intensity counseling on diet and exercise to patients. The modeled initial weight loss efficacy of IBT was based on results from the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study (DPPOS)Citation10, in which participants of the lifestyle intervention aged 60 years and older on average lost 7.5% of their initial weight over 12 months. A systematic review of weight-loss interventions for older adults with obesity showed the efficacy of IBT intervention ranges between 5.6% and 10%Citation24.

For pharmacotherapy treatment, there is a lack of clinical trial evidence specific to older adults. We synthesized weight management effects from four branded drugs (lorcaserin, phentermine plus topiramate, naltrexone plus bupropion, and liraglutide 3.0 mg) recently approved by the FDA, which showed the 1-year weight loss effects when combined with IBT range from 7 to 12.4% among enrolled participantsCitation14,Citation25–27. For modeling, a mean value of 9.7% was used as the first-year efficacy of pharmacotherapy in the base case analysis.

Some degree of weight regain is common, in part due to physiological adaptations occurring after weight loss, such as hormonal changes that lead to increased appetitive drive and decreased energy expenditure, as well as increased muscle efficiencyCitation28. According to the long-term outcome of the DPPOS, lifestyle intervention participants aged 65 and older gradually regain about 1/3 of initial weight loss over 5 years of follow-up and then maintain the remaining 2/3 weight lossCitation10. Similarly, participants of Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) showed about 1/2 of weight regain over the same periodCitation7. In contrast, there is a lack of evidence on weight maintenance for subjects who are on long-term pharmacotherapy. Outcomes from the SCALE Obesity and Prediabetes trial showed subjects who were on liraglutide 3.0 mg for 3 years lost 9.2% of body weight during the first year, but gradually regained 23% of initial weight loss by trial endCitation11. Similar weight regain patterns were observed in the XENDOS study, which used orlistat as an adjunct treatment to lifestyle interventionCitation27. Our study modeled the weight regain trend from DPPOS, in which all intervention participants started weight rebound after the first year of treatment and regained 1/3 of their lost weight by the end of the sixth year of the simulation period.

Treatment coverage utilization

An estimated 0.27% of Medicare beneficiaries are currently on IBT alone, and 3.6% are on combined anti-obesity medication and IBTCitation18,Citation29. Under a scenario with copay of anti-obesity drugs reduced from 100% (no Medicare coverage) to ∼25% (75% paid by Medicare) with proposed Medicare coverage expansion, an increase in treatment utilization would be expected. Joyce et al.Citation30 studied the relationship between drug use among the chronically ill and the copayment level of these drugs, and found that after copay doubled drug use dropped by 25–31%, which translates to 33.3% [25%/(1–25%)] to 44.9% [31%/(1–31%)] increase if copay were halved. We extrapolated a 50% [33.3% × 75%/50%] to 67% [44.9% × 75%/50%] increase in rate of treatment utilization if copay decreased by 75%. Therefore, we modeled 50% and 67% increases in the rate of treatment for scenarios reflecting a moderate and extensive Medicare coverage expansion.

Treatment adherence

The Medicare program covers IBT treatment for beneficiaries with obesity for up to 1 year in a primary care setting, provided the patient meets a minimum weight-loss threshold (3 kg) during the first 6 months. A study by Villareal et al.Citation31 assessed effects and adherence of a senior weight-loss program, and found 11% of participants were disqualified at month 6. For pharmacotherapy treatment, generic anti-obesity medications are approved for short-term use only because of side-effects. Therefore, our model assumes all participants terminate treatment within 1 year. There is a lack of data on the adherence of newer branded drugs approved for long-term use. In reference to adherence rates from other chronic medicationsCitation32,Citation33, we modeled a range of annual discontinuation rates at 28% (oral antidiabetics), 40% (bisphosphonates), and 65% (overactive bladder medications) for comprehensiveness.

Treatment costs

Reimbursement for IBT treatment is $25.19 per visit with 20 visits every yearCitation34. For pharmacotherapy treatment, the annual weighted average cost of anti-obesity medications is $813 before coverage expansion, based on current market share and wholesale acquisition cost of both generic and branded drugs (). In addition, we assumed all participants make monthly physician visits for weight-management counseling during the first year and an annual visit in subsequent years while in treatment. This assumption provides a conservative estimate of treatment costs. Average treatment cost was calculated based on the share of patients participating in therapy and adherence status. All costs and savings are in 2018 dollars.

Table 1. Weighted average anti-obesity medication annual cost.

Future anti-obesity pharmacotherapy

In addition to pharmacotherapies already approved by the FDA, several other compounds have shown promising weight-loss and safety results in recent clinical trialsCitation35. The Phase 2 trial of the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analog semaglutide for treatment of obesity has shown up to 13.8% mean weight reduction at week 52Citation36. Another dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist aided a 12.7% body-weight loss in patients with type 2 diabetesCitation37. FDA approval for one or more new compounds will likely be sought in the next few years. To study the potential budgetary impact from future medications, we modeled a hypothetical new anti-obesity drug starting from year 5. We modeled a potential new drug using the average efficacy from the two above-mentioned trials (weight loss of 13.3% in year 1) and annual cost equal to weighted average of all currently approved brand drugs ($4,513).

Simulation scenarios

To estimate the average 10-year treatment cost and medical expenditure saving per beneficiary, the differences were taken between outcomes from a “status quo” scenario that assumes continuation of 0.27% of Medicare beneficiaries on IBT alone and 3.6% on combined anti-obesity medication and IBT, and each of the following intervention scenarios:

Base case scenario: Assumed moderate weight loss from IBT (–7.5%) and IBT with pharmacotherapy (–9.7%), annual discontinuation rate of the branded drug at 40%, under moderate (50%) and extensive (67%) coverage utilization increase, respectively.

Weight-loss sensitivity scenario: Assessed model sensitivity using both upper and lower bounds of the weight loss range from both interventions, as informed by published literature on the efficacy of FDA-approved brand drugs. Assumed modest weight loss from IBT only (–5.6%) and with pharmacotherapy (–7.0%) as the lower bound, and high weight loss from IBT only (–10%) and with pharmacotherapy (–12.4%) as the upper bound. This scenario assumes moderate (50%) coverage utilization as in the base case scenario.

Alternative drug adherence scenario: Assessed the potential budget impact from long-term patient adherence to treatment by branded anti-obesity medications, assumed lower and higher annual discontinuation rates at 28% and 65%, respectively. Weight loss efficacy and treatment utilization are the same as in the base case scenario.

Impact of future drug scenario: Assumed hypothetical new drugs with 1-year weight loss efficacy at 13.3%, annual costs of $4,513 and 2% market share starting from year 5.

Results

The constructed representative sample of program-eligible Medicare beneficiaries (n = 50,000) has an average age of 72.9 years (standard deviation [SD] = 5.3 years), with a mean starting BMI of 32.8 kg/m2 (SD = 5.3) and HbA1c of 6.3 (SD = 1.2), and 46.1% male (). Under the moderate and extensive utilization expansion scenarios, 5,150 (10.3%) and 6,904 (13.8%) beneficiaries went through either only IBT (0.3% and 0.4%) or combined pharmacotherapy and IBT intervention (10.0% and 13.4%).

Table 2. Characteristics of simulated population.

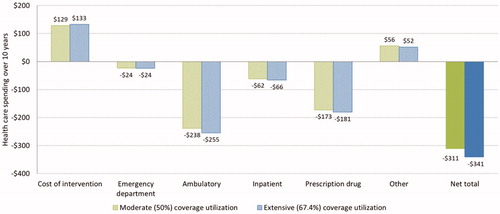

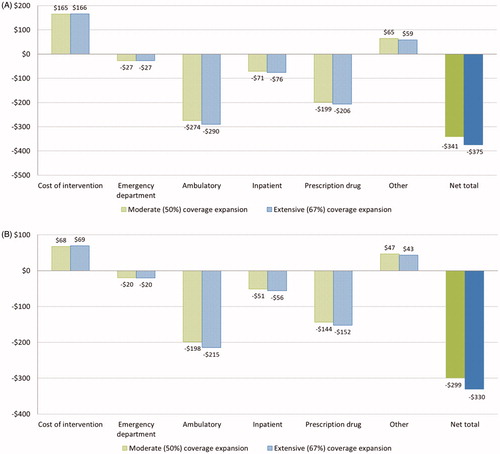

show the simulation results for Medicare beneficiaries. Each intervention participant is modeled to save $6,842 and $7,155 in total medical costs over 10 years under, respectively, the moderate and extensive coverage utilization assumptions. The corresponding average costs of intervention are $1,798 and $1,886 per participant (. Model simulations suggest the majority of savings come from reduced spending on ambulatory care services (–$6,277 to –$6,414) and prescription drugs (–$4,003 to –$4,041), while spending from “other” services increases ($3,044–$2,853). When taking the entire Medicare population (both treated and untreated) into consideration, the estimated average 10-year budget savings per beneficiary are $308 and $339 under both coverage utilization assumptions ().

Figure 2. 10-year treatment cost and Medicare budget saving per beneficiary. Data shown are estimated average treatment cost and saving to Medicare spending per (a) treated Medicare beneficiary, and (b) Medicare beneficiary (both treated and untreated).

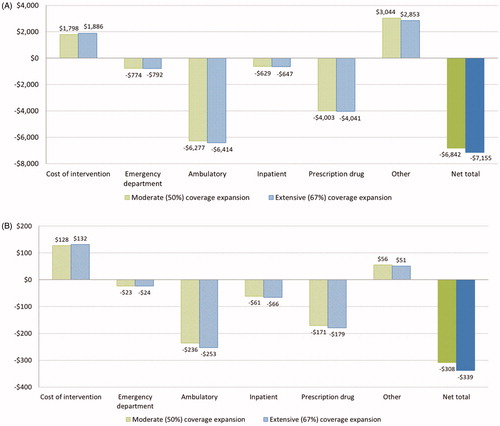

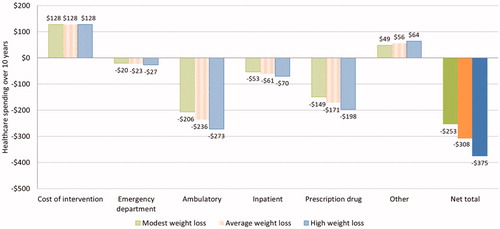

Results of the budget impact sensitivity analysis on weight loss effect and drug adherence rate are shown in and . Under moderate (50%) coverage utilization expansion, the estimated average 10-year net savings per Medicare beneficiary are $253 and $375 with modest and high weight loss efficacy assumptions, respectively, indicating a potential ±22% variation for budget savings (). Depending on the long-term discontinuation rate of branded medications, the average savings are estimated to be $299–$341 under moderate coverage utilization and $330–$375 under extensive utilization, an ∼±7% variation compared to the base case (). As the Medicare population is projected to increase from 60 million beneficiaries today to more than 80 million by 2030Citation38, the program is expected to save $19–$21 billion overall over the next 10 years under moderate coverage expansion, and $22–$24 billion under extensive expansion.

Figure 3. Weight loss effect sensitivity analysis on 10-year treatment cost and Medicare budget saving per Medicare beneficiary (moderate coverage expansion).

Figure 4. Drug adherence sensitivity analysis on 10-year treatment cost and Medicare budget saving per Medicare beneficiary. Data shown are estimated average treatment cost and saving to Medicare spending per beneficiary (both treated and untreated) assuming annual discontinuation rate of branded drugs at (a) 28% and (b) 65%, respectively.

With the introduction of a hypothetical new weight-loss drug in the middle of the studied time horizon, the model predicted $311–$341 savings per Medicare beneficiary under the moderate and extensive coverage utilization assumptions, a 1% increase over the base case ().

Discussion

Since passage of the Affordable Care Act, Medicare has expanded coverage on IBT sessions for beneficiaries with obesity for up to 1 year. However, IBT coverage is widely under-utilized and excludes access to anti-obesity pharmacotherapy. Expanding Medicare coverage to both IBT and pharmacotherapy can potentially improve the overall health of beneficiaries with obesity, which in turn could lead to long-term reductions in healthcare spending. In this study, we examined the economic benefit to Medicare covering anti-obesity pharmacotherapy as well as IBT and estimated the potential budget impact to Medicare. Considering the high prevalence of obesity among senior adults, only a small proportion of eligible beneficiaries underwent systematic weight management treatment. We modeled an overall usage increase from 3.87% to 5.81% (50% increase under “moderate” assumption) and 6.46% (67% increase under “extensive” assumption) if Medicare expands coverage on obesity treatment. Even under modeled scenarios only a small proportion of about 3.5–3.9 million eligible beneficiaries would participate in the weight loss intervention when estimated based on total enrollment of the Medicare program (60.4 million, December 2018).

Few published studies provide budgetary analysis of weight management among Medicare beneficiaries. Thorpe et al.Citation39 modeled the impact of 10–15% weight loss on Medicare spending among the overweight and beneficiaries with obesity. They estimated an initial weight loss of 10% followed by 90% weight rebound over 10 years likely would result in gross savings of $8,287–$9,826 (in 2018 dollars) per patient over a decade, consistent with the direct medical saving from our base case analysis ($8,640–$9,041 without considering the $1,798–$1,886 intervention costs).

A strength of this analysis comes in the breakdown of estimated cost savings by expenditure category. Despite inpatient hospital care accounting for the largest share of per capita Medicare spendingCitation40, most of the projected savings from obesity intervention are from reduced use of ambulatory services and prescription drugs ($10,280–$10,455 in total). This reflects that complications of obesity are mostly chronic conditions manageable through ambulatory visits and medication. Reducing excess weight leads to lower risk of obesity complications and slower disease progression, which in turn reduces the need for ambulatory visits and prescription medications. In contrast, there is a slight increase in the spending from the “other” group ($3,044–$2,853), which comprises myriad items such as home health service, dental service, glasses, wheelchairs, and prosthesis. This increase can be explained by higher utilization of long-term care and other wellness resources resulting from improved health and increased longevity among participants. This explanation is supported by our model prediction that total Medicare enrollment would increase by 0.3–0.5 million over the next 10 years compared to the status quo scenario, due to increased longevity from coverage expansion. As the result, Medicare will expect higher saving in total medical expenditure among intervention participants at the cost of a relatively small increase in spending.

Before 2012 there were few pharmaceutical treatments for obesity. Early weight-loss drugs were introduced and later withdrawn because of their adverse side-effects. Modern anti-obesity pharmacotherapies were approved for long-term use by the FDA between 2012 and 2014. With continuous research and development, new pharmacotherapies are expected to be approved and available to patients in the near future. As a conservative approach, we modeled a hypothetical future drug scenario in which a new medication for the treatment of obesity with the average efficacy from two recent Phase 2 trials and cost of existing branded drugs is launched in the market. Given the small market share, the introduction of this new drug only produced minimal impact from a budget perspective.

This study has limitations. First, due to the scarcity of studies on the efficacy of pharmacotherapies among seniors with obesity, the simulated weight loss and long-term maintenance effects were derived from outcomes of clinical trials, in which senior adults were under-represented. Thus, the modeled weight change over time is not a direct reflection of actual results from population representative of Medicare beneficiaries. To account for the influence of this uncertainty, our sensitivity analysis showed variations in treatment efficacy could result in up to 22% fluctuation in estimated budget saving. Nevertheless, a recent post-hoc analysis of trial data showed similar weight-loss efficacy of liraglutide 3.0 mg in individuals aged ≥65 years vs those <65 yearsCitation41. Second, the model omits potential side-effects from anti-obesity medications and extra treatment cost incurred due to these conditions. There is a lack of evidence on safety and tolerability of pharmacotherapy on elderly adults since most clinical trials purposely excluded them from participation. However, older adults—because of their poorer health conditions—potentially are at greater risk for chronic disease onset than young adults. Third, due to lack of data we assumed the current total market share distribution of anti-obesity medications also applies to the Medicare market. However, it is possible that, after coverage expansion, more beneficiaries would prefer branded medications leading to higher drug acquisition costs for Medicare. Based on our analysis, if market share of branded anti-obesity medication doubled from current the 17% to 34%, the estimated 10-year budgetary savings would drop to 80% to 85% of the base case scenario—still providing savings to Medicare (the estimated budget impact of market share and other key model assumptions are listed in Supplementary Table 1). Fourth, the medical expenditure prediction equations in our model were estimated using regression analysis, as described in the method. While we do not explicitly model the direct cost linked to some complications of obesity (e.g. osteoarthritis) and some medical services (e.g. home care), the inclusion of BMI in the regression equations as a continuous measure for obese individuals is intended to reflect the relationship between body weight and annual medical expenditures as well as to capture potential savings due to weight loss.

Conclusion

Under proposed Medicare coverage expansion policy on weight management, the long-term saving on gross Medicare outlays due to improved health is likely to exceed the cost of anti-obesity interventions (IBT and/or pharmacotherapy), leading to a projected net budget saving of $20–$23 billion over 10 years. While this study estimates the potential costs and savings for a weight management policy specific to the US, our findings suggest the possibility for economic benefits globally as other countries devise strategies and policies to address rising medical costs that in part are attributed to the obesity epidemic.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Novo Nordisk Inc. funded this study and medical writing and participated in study conceptualization and design, interpreting results, manuscript review, and approval of the final version.

Declaration of financial/other interests

AR, RG, and TZ are employees of Novo Nordisk Inc., a global healthcare company with products to treat people with obesity. FC, WS, and TK provide paid consulting services to federal and state governments, non-profit entities, and for-profit entities. The authors report no other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (13.4 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank Tim Dall of IHS Markit for assistance with manuscript preparation.

Notes

1 Belviq is a registered mark of Eisai Inc.

2 Contrave is a registered mark of Nalpropion Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

3 Qsymia is a registered mark of VIVUS, Inc.

4 Saxenda is a registered mark of Novo Nordisk A/S.

References

- Tremmel M, Gerdtham UG, Nilsson PM, et al. Economic burden of obesity: a systematic literature review. Int.J.Environ.Res.Public Health. 2017;14:E435.

- Li Q, Blume SW, Huang JC, et al. The economic burden of obesity by glycemic stage in the United States. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33:735–748.

- Wang YC, McPherson K, Marsh T, et al. Health and economic burden of the projected obesity trends in the USA and the UK. Lancet. 2011;378:815–825.

- Milken Institute. Weighting down America: the health and economic impact of obesity. 2016 November [cited 2018 Mar 19]. Available from: https://www.milkeninstitute.org/reports/weighing-down-americahealth-and-economic-impact-obesity

- US Census Bureau. National Population Projections 2018 Sep 6. 2017 [cited 2019 Feb 13]. Available from: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/popproj.html.

- Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, et al. Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA. 2016;315:2284–2291.

- Eight-year weight losses with an intensive lifestyle intervention: the look AHEAD study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014;22:5–13.

- Ali MK, Echouffo-Tcheugui J, Williamson DF. How effective were lifestyle interventions in real-world settings that were modeled on the Diabetes Prevention Program?. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31:67–75.

- Dall TM, Storm MV, Semilla AP, et al. Value of lifestyle intervention to prevent diabetes and sequelae. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48:271–280.

- Knowler WC, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, et al. 10-year follow-up of diabetes incidence and weight loss in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet. 2009;374:1677–1686.

- Le Roux CW, Astrup A, Fujioka K, et al. 3 Years of liraglutide versus placebo for type 2 diabetes risk reduction and weight management in individuals with prediabetes: a randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet. 2017;389:1399–1409.

- Aronne L, Shanahan W, Fain R, et al. Safety and efficacy of lorcaserin: a combined analysis of the BLOOM and BLOSSOM trials. Postgrad Med. 2014;126:7–18.

- Wadden TA, Foreyt JP, Foster GD, et al. Weight loss with naltrexone SR/bupropion SR combination therapy as an adjunct to behavior modification: the COR-BMOD trial. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2011;19:110–120.

- Shin JH, Gadde KM. Clinical utility of phentermine/topiramate (Qsymia) combination for the treatment of obesity. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2013;6:131–139.

- Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA. Long-term drug treatment for obesity: a systematic and clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311:74–86.

- Cabrerizo GL, Ramos-Levi A, Moreno LC, et al. Update on pharmacology of obesity: benefits and risks. Nutr Hosp. 2013;28:121–127.

- Intensive Behavioral Therapy (IBT) for Obesity. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Final Coverage Decision Memorandum for Intensive Behavioral Therapy for Obesity. 2012 Mar 9 [cited 2019 Feb 13]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?&NcaName=Intensive%20Behavioral%20Therapy%20for%20Obesity&bc=ACAAAAAAIAAA&NCAId=253.

- Noelia D, Eamon M, Lori H, et al. Estimating the effects of federal policies targeting obesity: challenges and research needs. CBo Blog. 2015 Oct 26 [cited 2018 Mar 14]. Available from: https://www.cbo.gov/publication/50877.

- The Treat and Reduce Obesity Act of 2017 (S.830/H.R.1953). 2017 Apr 5 [cited 2019 Feb 13]. Available from: https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/1953.

- Chen F, Su W, Becker SH, et al. Clinical and economic impact of a digital, remotely-delivered intensive behavioral counseling program on medicare beneficiaries at risk for diabetes and cardiovascular disease. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0163627.

- Su W, Huang J, Chen F, et al. L. Modeling the clinical and economic implications of obesity using microsimulation. J. Med. Econ. 2015;18:886–897.

- Overweight, obesity, and health risk. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:898–904.

- Semilla AP, Chen F, Dall TM. Reductions in mortality among Medicare beneficiaries following the implementation of Medicare Part D. Am J Manag Care. 2015; 21:s165–s171.

- Felix HC, West DS. Effectiveness of weight loss interventions for obese older adults. Am J Health Promot. 2013;27:191–199.

- Garvey WT, Ryan DH, Look M, et al. Two-year sustained weight loss and metabolic benefits with controlled-release phentermine/topiramate in obese and overweight adults (SEQUEL): a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 extension study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95:297–308.

- Smith SR, Weissman NJ, Anderson CM, et al. Multicenter, placebo-controlled trial of lorcaserin for weight management. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:245–256.

- Torgerson JS, Hauptman J, Boldrin MN, et al. XENical in the prevention of diabetes in obese subjects (XENDOS) study: a randomized study of orlistat as an adjunct to lifestyle changes for the prevention of type 2 diabetes in obese patients. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:155–161.

- Anastasiou CA, Karfopoulou E, Yannakoulia M. Weight regaining: from statistics and behaviors to physiology and metabolism. Metab Clin Exp. 2015;64:1395–1407.

- Hampp C, Kang EM, Borders-Hemphill V. Use of prescription antiobesity drugs in the United States. Pharmacotherapy. 2013;33:1299–1307.

- Joyce GF, Escarce JJ, Solomon MD, et al. Employer drug benefit plans and spending on prescription drugs. JAMA. 2002;288:1733–1739.

- Villareal DT, Chode S, Parimi N, et al. Weight loss, exercise, or both and physical function in obese older adults. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1218–1229.

- Yeaw J, Benner JS, Walt JG, et al. Comparing adherence and persistence across 6 chronic medication classes. JMCP. 2009;15:728–740.

- Vrijens B, Antoniou S, Burnier M, et al. Current situation of medication adherence in hypertension. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:100.

- Hoerger TJ, Crouse WL, Zhuo X, et al. Medicare's intensive behavioral therapy for obesity: an exploratory cost-effectiveness analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48:419–425.

- Srivastava G, Apovian C. Future pharmacotherapy for obesity: new anti-obesity drugs on the horizon. Curr Obes Rep. 2018;7:147–161.

- O'Neil PM, Birkenfeld AL, McGowan B, et al. Efficacy and safety of semaglutide compared with liraglutide and placebo for weight loss in patients with obesity: a randomised, double-blind, placebo and active controlled, dose-ranging, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2018;392:637–649.

- Frias JP, Nauck MA, Van J, et al. Efficacy and safety of LY3298176, a novel dual GIP and GLP-1 receptor agonist, in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised, placebo-controlled and active comparator-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2018;392:2180–2193.

- The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System. Washington, DC; 2017 Jun 15.

- Thorpe KE, Yang Z, Long KM, et al. The impact of weight loss among seniors on Medicare spending. Health Econ Rev. 2013;3:7.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicare spending at the end of life: a snapshot of beneficiaries who died in 2014 and the cost of their care. 2016 Jul 14 [cited 2018 Mar 23]. Available from https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-spending-at-theend-of-life/

- Domenica MR, Scott K, Robert FK. Age no impediment to effective weight loss with liraglutide 3.0 mg: data from two randomized trials. Conference: XXI I Congresso Brasileiro de Nutrologia; 2017.