Abstract

Aims: OnabotulinumtoxinA is recommended by NICE for the treatment of chronic migraine. This economic evaluation provides updated estimates of the cost-effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA for chronic migraine using new utility estimates in an existing model structure.

Methods: A previously published model was revised to include EQ-5D utility estimates from a large observational study (REPOSE; n = 633). Efficacy data were taken from the pooled phase III PREEMPT clinical trial program, while resource utilization estimates were obtained from the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS). The model estimated costs and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) gained over 2 years from the UK NHS perspective.

Results: OnabotulinumtoxinA treatment resulted in total discounted incremental costs of £1,204 and an incremental discounted QALY gain of 0.07 compared with placebo in patients with chronic migraine who have previously failed three or more preventive treatments, corresponding to an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of £16,306 per QALY gained. Scenario analysis showed that the administration of onabotulinumtoxinA by a specialist nurse rather than a neurology consultant reduced the ICER from £16,306 to £13,832 per QALY gained. Removal of the positive stopping rule recommended in current NICE guidance increased the ICER to £20,768 per QALY for onabotulinumtoxinA vs. placebo. Combining these two scenarios produced an ICER of £17,686 per QALY gained.

Conclusion: NICE recommended onabotulinumtoxinA for the prevention of chronic migraine in 2012 amid concerns about the uncertainty of ICER estimates, with a positive stopping rule used to manage some of these uncertainties. Since the publication of the NICE guidance, the REPOSE study provides a more recent source of utility data based on real-world evidence. The results of analyses including these utilities suggest that the application of the positive stopping rule may not be necessary to ensure cost-effectiveness and that this aspect of the current NICE guidance for onabotulinumtoxinA may merit reconsideration.

Introduction

Chronic migraine is a disabling neurological disorder affecting an estimated 1.4 to 2.2% of adults globallyCitation1. The International Classification of Headache Disorders (Third Edition) defines chronic migraine as the occurrence of 15 or more headache days per month for more than three months, of which at least eight days per month have the features of migraine (typically a unilateral, pulsating headache of moderate-to-severe pain intensity, accompanied by nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia, and/or aura symptoms)Citation2. Compared with episodic migraine (characterised by headaches on less than 15 days per month), patients with chronic migraine have significantly greater disease burden including more headache days, more headache-related disability, and poorer health-related quality of life (HRQoL), which is accompanied by greater healthcare resource use (such as visits to the emergency department) and socioeconomic burden (such as absence from work)Citation3–7.

Clinical guidelines recommend beta-blockers, anti-epileptics, and tricyclic antidepressants as options for first-line preventive treatment of chronic migraine in the UKCitation8–12. The anti-epileptic drug topiramate is licensed for migraine prophylaxisCitation13, while the other options are prescribed off-label. OnabotulinumtoxinA (Botox; Allergan Inc., Dublin, Ireland) is licensed for prophylaxis of headache in adults with chronic migraine in the UKCitation14 and is recommended for patients who have previously received three or more preventive treatments in accordance with the technology appraisals conducted by the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in 2012 and the Scottish Medicines Consortium (SMC) in 2017Citation15,Citation16. Recent European clinical guidelines from the European Headache Foundation (EHF) recommend onabotulinumtoxinA as a preventive treatment for chronic migraine in patients who have failed at least two to three other migraine prophylacticsCitation17.

The efficacy of onabotulinumtoxinA was evaluated in two identical phase III trials in patients with chronic migraine (PREEMPT 1 and 2), each with a 24-week randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase followed by a 32-week open-label phaseCitation18–21. Pooled analysis of the randomized phase of the PREEMPT trial program (n = 1,384; mean age of 41.3; 86.4% female; mean of 19.9 headache days per 28 days at baseline) revealed a statistically significant reduction in headache days in patients receiving onabotulinumtoxinA compared with placebo at week 24 (−8.4 vs. −6.6; p < .001)Citation21. OnabotulinumtoxinA was also shown to reduce the frequency and severity of headaches, with significant differences favoring onabotulinumtoxinA over placebo for frequencies of headache episodes, migraine days, migraine episodes, moderate or severe headache days, and total hours of headacheCitation21. Statistically significant improvements in HRQoL, captured using the Migraine Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire v2.1 (MSQ)Citation22, were observed in the PREEMPT trials. Post-hoc analysis of a subgroup of patients from PREEMPT whose condition had failed to respond to at least three oral preventive treatments (n = 439) also demonstrated the superior efficacy of onabotulinumtoxinA over placebo (−7.4 vs. −4.7 headache days; p < .001) and statistically significant improvements in HRQoLCitation15.

A cost-effectiveness model was developed by Batty et al., using a published mapping algorithm for the MSQ to the EuroQol Five-Dimensions (EQ-5D) for generating utility estimatesCitation23,Citation24. The model produced a deterministic base case incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of £17,212 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained for the subgroup of patients who had received three or more prior prophylactics. This indicated that onabotulinumtoxinA was cost-effective compared with placebo at the commonly referenced NICE threshold for NHS treatment recommendation of £20,000 to £30,000 per QALY gainedCitation23,Citation25.

Based on the clinical and economic data from the subgroup of PREEMPT, NICE recommended onabotulinumtoxinA for the prophylaxis of headaches in adults with chronic migraine that had not responded to at least three prior oral preventive treatments and was appropriately managed for acute medication overuse in single technology appraisal 260 (TA260)Citation15. However, concerns were raised about mapping the MSQ scores to the EQ-5D and the non-monotonicity of the resulting utilities (values did not consistently decrease as the severity of the health states increased), as well as the duration of follow up in the PREEMPT program (56 weeks)Citation20. Furthermore, stopping rules were applied as part of the recommendation to manage uncertainty in the ICER estimates, which consisted of withdrawing treatment in patients whose chronic migraine 1) failed to respond to onabotulinumtoxinA treatment (negative stopping rule) or 2) responded to onabotulinumtoxinA and was re-classified as episodic migraine (positive stopping rule). OnabotulinumtoxinA was later recommended by the SMC for the subgroup of patients who had received three or more prior prophylactics whose medication overuse has been appropriately managedCitation16. Stopping rules were not explicitly included in the SMC’s advice, with the positive stopping rule considered to be difficult to implement in practiceCitation16.

Since the assessment of onabotulinumtoxinA by NICE in 2012, several observational studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA in the real-world setting in Europe, including the REPOSE study (n = 633)Citation26. REPOSE is a prospective, non-interventional observational study measuring healthcare resource utilization and patient-reported outcomes, including headache day frequency and HRQoL (measured using MSQ and EQ-5D)Citation27. Patients with chronic migraine were treated with onabotulinumtoxinA for two years in centres across Germany, Italy, Norway, Russia, Spain, Sweden, and the UK. The REPOSE study demonstrated that routine clinical use of onabotulinumtoxinA is effective and safe, with sustained reduction in headache-day frequency and significant improvement in health-related quality of life over a two-year periodCitation26.

A recent review that included all European real-world studies with over 150 patients found that onabotulinumtoxinA treatment significantly improved a range of headache symptoms and impact measures compared to baseline (p < .01)Citation28–33. Along with smaller observational studies conducted in European countries, a reduction in the number of headache days from baseline was consistently reported, as well as reductions in headache severity and painCitation26,Citation30–35, with the effect reported in the real-world of a similar or greater magnitude as that observed in the PREEMPT trialCitation20,Citation21. Furthermore, the effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA has been demonstrated beyond one yearCitation26,Citation32,Citation33,Citation36–40.

The aim of the economic evaluation described in this paper was to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA compared with placebo in patients who have previously received three or more preventive treatments, using a revised version of the published economic model accepted by NICECitation15,Citation23 with more recent utility data and cost estimates. The model has been revised only in order to incorporate utility values derived directly from EQ-5D data collected in the REPOSE studyCitation26 and updated unit costs relevant for the National Health Service (NHS) in England.

Methods

The model structure has been summarised briefly here, with further information available in the publication of the original model by Batty et al.Citation23. The model inputs were chosen to conform with the preferred ICER estimate of the NICE appraisal committee as outlined in the final guidance document (TA260)Citation15, unless otherwise stated. Differences between the original and revised models in terms of data and assumptions used in the base case are outlined in .

Table 1. Base case inputs and assumptions.

Patient population

This analysis focused on patients with chronic migraine who have previously received three or more oral preventive therapies (439 patients in the PREEMPT program [32%]), which the NICE appraisal committee considered to be the clinically relevant patient populationCitation15. The previous economic evaluation presented a secondary analysis of this populationCitation23.

Comparator

At the time of writing, onabotulinumtoxinA was the only treatment option recommended by NICE for the patient population of interestCitation10. Therefore, the placebo arm of PREEMPT (as a proxy for standard care with acute medications such as triptans and any consultant appointments associated with managing acute treatment) was used as the comparator, as per NICE guidance (TA260)Citation15.

Model structure

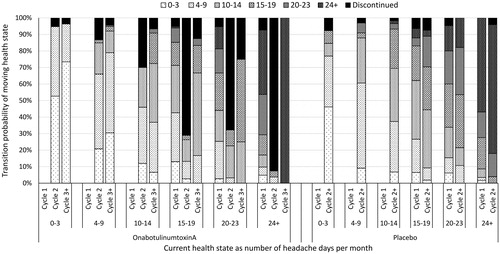

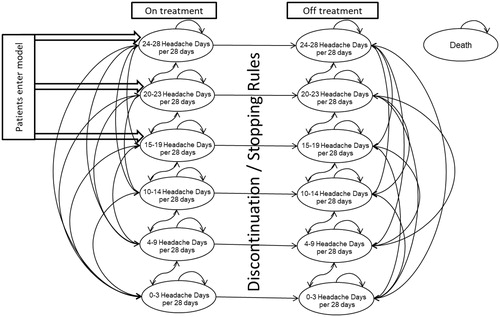

A Markov model consisting of thirteen health states was previously developed by Batty et al.Citation23 to estimate the cost-effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA compared with placebo in patients with chronic migraine using Microsoft Excel 2010. Health states were categorised according to the number of headache days per 28 days: three representing episodic migraine (0 to 3, 4 to 9, and 10 to 14) and three representing chronic migraine (15 to 19, 20 to 23, and 24 and above) for each treatment state (on or off treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA) (). The final health state was death. The rationale for selecting these health states has been outlined previouslyCitation23.

Figure 1. Markov model diagram of onabotulinumtoxinA for the preventive treatment of chronic migraine. Reproduced from Batty et al.Citation23.

Patients entered the model in one of the chronic migraine health states, according to the baseline number of headache days of patients whose condition had failed to respond to at least three preventive treatments from PREEMPT. Transitions between health states were assumed to occur at the start of each 12-week cycle (based on the treatment schedule of PREEMPT) and were calculated using the three or more prior prophylactics subgroup, as per the subgroup analysis from the original model ()Citation23. Cycle 1 (weeks 0 to 12) data from PREEMPT were used independently for both arms because a larger decrease in headache days was observed in this cycle than experienced in subsequent cycles. For the onabotulinumtoxinA arm, four additional cycles of data (weeks 12 to 24, 24 to 36, 36 to 48, and 48 to 56) were combined for cycle 2 and beyond. Data from one additional cycle were available for the placebo arm and used for all cycles beyond cycle 1. Discontinuation probabilities were obtained from observed values in PREEMPT or the application of stopping rules (as described below). Patients who discontinued were assumed to follow placebo transition probabilities and to have no costs beyond the resource use associated with their health state. Because there is no evidence supporting disease-specific mortality, background mortality was modelled for both arms using death rates from the national life tables for EnglandCitation41 combined with the demographics of the PREEMPT population. Further details of the method and assumptions for calculating transition probabilities are described by Batty et al.Citation23.

Time horizon and perspective

A time horizon of two years was used in accordance with the preferred ICER estimate of the NICE appraisal committeeCitation15. The impact of using a three-year time horizon was investigated in scenario analyses, supported by the availability of longer-term observational studies since the publication of NICE guidance (TA260) in 2012. The perspective of the analysis was the NHS in England, excluding patient expenses, caregiver costs, and lost work productivity. The cost year was 2017 and future costs and QALYs were discounted at a rate of 3.5%, which conforms with current NICE methodologyCitation25.

Stopping rules

Stopping rules allow patients to withdraw from onabotulinumtoxinA according to the responder criteria applied. In this analysis, the preferred stopping rules of the NICE appraisal committee were applied to the cost-effectiveness model, as per Batty et al.Citation23.

A positive stopping rule was implemented to model withdrawal from onabotulinumtoxinA in the event of a sustained response after Year 1Citation23. A prospective observational study conducted in the US found that 24% of patients whose migraine responded to treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA were able to withdraw and maintain the benefit for at least six monthsCitation40. In the absence of alternative data, 24% of successfully-treated patients in the onabotulinumtoxinA arm were assumed to stop treatment in the model, all of whom had transitioned to episodic migraine health states by the end of Year 1. These patients were assumed to remain in the same health state until the end of Year 2 and have costs associated with placebo. The same assumptions apply to Year 3, which was investigated in scenario analyses here. Scenarios investigating the impact of removing the positive stopping rule on the ICER estimate are presented in this study.

A negative stopping rule was implemented on the advice of clinical experts to account for withdrawal from onabotulinumtoxinA in patients experiencing insufficient benefitCitation23. Treatment discontinuation in patients who do not achieve a reduction of headache days of 30% or more within two 12-week treatment cycles was considered clinically relevant and accepted by the NICE appraisal committeeCitation15. The negative stopping rule was applied to transition probabilities of the onabotulinumtoxinA arm and resulted in increased discontinuations in cycle 2, as illustrated in .

HRQoL and utility values

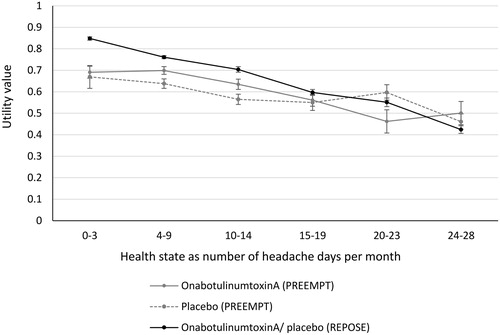

In the original model, utility values were derived from the MSQ for the subgroup of patients who had previously received three or more preventive therapies from PREEMPTCitation23. MSQ scores were mapped to the EQ-5D using an algorithm published by Gillard et al.Citation24 to generate treatment-specific utility values for each health state. This captured the benefits of onabotulinumtoxinA on HRQoL beyond the reduction in headache days, such as reductions in headache frequency and severity. However, this method of calculating utility estimates produced an anomaly; patients in the 20–23 headache days per 28 days health state had a lower utility than those in the 24–28 headache days health state in the onabotulinumtoxinA arm, a phenomenon known as non-monotonicity. This was most likely due to the small sample size in the most severe health state of 24–28 headache days and the use of a mapping algorithm.

The revised model produced utility values directly from the EQ-5D data collected in the much larger REPOSE studyCitation26. The EQ-5D was administered at baseline and each follow-up visit (at intervals of approximately 12 weeks) in patients receiving onabotulinumtoxinACitation27. EQ-5D scores were categorised according to the number of headache days as per the health states in the model and utilities were calculated using the UK value set. Because REPOSE was a non-interventional observational study on the use of onabotulinumtoxinA in real-world clinical practice, the same utility values were applied to both the onabotulinumtoxinA and placebo arms in the model. This assumes there is no benefit from onabotulinumtoxinA beyond the reduction in headache days per 28 days, which is likely to be a conservative assumption. The REPOSE study provides an alternative source of utility data that is based on a large number of observations where EQ-5D data were collected directly. This avoids the introduction of “noise” by the use of a mapping algorithm from MSQ to EQ-5D and eliminates non-monotonicity. A comparison of utilities derived from the PREEMPT and REPOSE studies is provided in .

Health care resource use and costs

Patients in the onabotulinumtoxinA arm of the model were assumed to receive 155–195 Units of onabotulinumtoxinA per 12-week cycle in accordance with the PREEMPT treatment regimen. The cost associated with administration of onabotulinumtoxinA was assumed to be £276.40 for one 200 Unit vialCitation42 and £152 for one face-to-face follow-up outpatient appointment with a consultant neurologist each cycle (producing a total treatment cost of £428.40 per 12-week cycle)Citation43. Patients in the placebo arm were assumed to have one outpatient appointment with a consultant every 24 weeks for monitoring of acute treatment (£76 per 12-week cycle). These administration and monitoring assumptions align with the preferred assumptions of the Evidence Review Group (ERG) of the NICE appraisal (TA260)Citation15.

Administration of onabotulinumtoxinA by a specialist nurse was investigated as a scenario analysis. The total cost of onabotulinumtoxinA treatment is £379.90 per 12-week cycle in this scenario, based on 15 min of patient contact time with a specialist nurse (£27.50)Citation44 and monitoring by a consultant neurologist at the same frequency as the placebo arm (£76 per 12-week cycle).

The cost of care applied to each health state was informed by the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS)Citation3 using the same approach as Batty et al.Citation23, with the exception that all unit costs were updated for the cost year of 2017Citation43–45. The elements of care relevant for patients with chronic migraine were general practitioner (GP) visits (£31)Citation44, emergency department (ED) visits (£104.24)Citation43, non-elective hospitalizations (£591.40)Citation43, and triptan use (£3.25 per triptan; calculated as the weighted mean cost of triptans prescribed in England)Citation45. shows the cost per cycle for each health state.

Table 2. Cost of care per 12-week cycle by health state.

Sensitivity analyses

Scenario analyses were conducted to assess uncertainty around key parameters in the cost-effectiveness model. Scenarios tested included: replacing utility values from REPOSE with treatment-specific utilities derived from PREEMPT; administration of onabotulinumtoxinA by a specialist nurse rather than a consultant; increasing the time horizon from 2 to 3 years; and removing the positive stopping rule. These were selected according to the data varied in the revised version compared with the original model and key scenarios identified as important by Batty et al.Citation23.

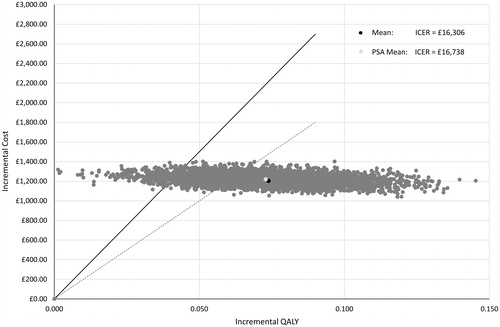

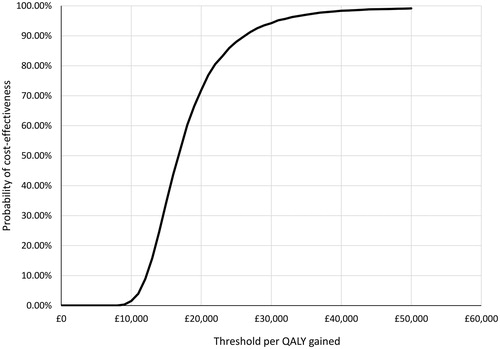

Probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) was performed to test the uncertainty of all model inputs except drug costs. Five thousand simulations were performed using random sampling from the 95% confidence intervals of the parameters. Outputs of the PSA were presented as a cost-effectiveness plane, with results that were cost-effective at a willingness-to-pay threshold of £20,000 and £30,000 per QALY represented using a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve.

Results

Deterministic base case results

Treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA resulted in total discounted incremental costs of £1,204 (£2,827 vs. £1,623) and an incremental discounted QALY gain of 0.07 (1.21 vs. 1.13) compared with placebo in patients with chronic migraine who have previously failed three or more preventive treatments (). This corresponds to an ICER of £16,306 per QALY gained for onabotulinumtoxinA compared with placebo from an NHS England perspective. The deterministic base case assumptions include a two-year time horizon, administration and monitoring by a consultant neurologist as an outpatient, use of EQ-5D-derived utilities from REPOSE, and application of both positive and negative stopping rules.

Table 3. Deterministic base case results with disaggregated costs and QALYs.

The incremental cost associated with onabotulinumtoxinA was driven by increased treatment costs (including drug costs and the cost of administration and monitoring) of £1,337 compared with placebo. This was partially offset by reduced healthcare resource utilisation for patients receiving onabotulinumtoxinA compared with placebo, including GP appointments (-£43), visits to the emergency department (-£32), hospitalization (-£36), and triptan use (-£16). The application of the same utility values to both arms for each health state resulted in a QALY benefit associated with onabotulinumtoxinA treatment because more patients transitioned to a better health state compared with placebo. Disaggregated costs and QALYs are presented in .

Scenario analyses

Source of utility data

The impact of using a new source of HRQoL data on the updated ICER estimate was assessed by replacing the utilities from the EQ-5D of REPOSE with those used in the original model, which were derived by mapping MSQ scores from the three or more previous prophylactics subgroup of PREEMPT to the EQ-5D ()Citation23,Citation24. Using utility values from PREEMPT while retaining all other base case assumptions, the ICER increased from £16,306 to £19,599 per QALY gained ().

Table 4. Deterministic base case results and scenario analysesTable FootnoteΛ.

Administration of onabotulinumtoxinA and time horizon

Changing the assumptions around the administration of onabotulinumtoxinA and the time horizon had a substantial effect on the ICER (). Administration of onabotulinumtoxinA by a specialist nurse rather than by a neurology consultant reduced the ICER from £16,306 to £13,832 per QALY gained for onabotulinumtoxinA compared with placebo. This scenario assumes that patients in both arms of the model have consultant appointments at the same frequency, either for monitoring preventive treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA or tailoring the management of chronic migraine with acute medication in the placebo arm.

Extending the time horizon of the model from two years to three years, based on an extrapolation of the one-year PREEMPT program and the longer real-world studies demonstrating continued efficacy beyond one year, increased the incremental QALY gain of the deterministic base case from 0.07 to 0.12. This produced an ICER of £11,629 per QALY gained for onabotulinumtoxinA compared with placebo.

The combined effect of nurse administration of onabotulinumtoxinA and a three-year time horizon resulted in an ICER of £9,801 per QALY gained, substantially below the commonly referenced NICE threshold for the recommendation of £20,000–£30,000 per QALY.

Positive stopping rule

The application of a positive stopping rule is considered difficult in clinical practice because it involves withdrawing treatment from patients who have responded well to onabotulinumtoxinA. The impact of removing this rule on the ICER was investigated in scenario analyses. When no other base case assumptions were varied, removal of the positive stopping rule increased incremental costs of treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA by £311, producing an ICER of £20,768 per QALY compared with placebo (). However, when the removal of the positive stopping rule was combined with administration by a specialist nurse or a time horizon of three years, onabotulinumtoxinA produced ICERs of £17,686 and £15,613 per QALY gained, respectively. Combination of all three scenarios (no positive stopping rule, administration by a specialist nurse, and a three-year time horizon) reduced the ICER from the deterministic base case of £16,306 to £13,245 per QALY gained.

Probabilistic sensitivity analyses

To explore parameter uncertainty, a PSA on all model inputs except for drug costs was conducted. Due to the mutually exclusive nature of the health states that can be divided into a number of beta distributions, nested beta distribution sampling was applied to the transition probability matrices. In PSA using the assumptions specified above, 5,000 simulations generated a mean probabilistic ICER of £16,738 that is relatively close to the estimated deterministic ICER of £16,306 (). OnabotulinumtoxinA has a 71.9% chance of being cost-effective at a threshold of £20,000 per QALY gained and 94.2% of being cost effective at a threshold of £30,000 per QALY gained ().

Discussion

The revised economic model presented here demonstrates that onabotulinumtoxinA represents a cost-effective treatment for the prevention of chronic migraine in patients who have previously received three or more oral prophylactics in the UK. The ICER of onabotulinumtoxinA vs. placebo was below the £20,000 to £30,000 per QALY threshold for NHS treatment recommendation by NICE when the preferred assumptions of the NICE appraisal committee (TA260) were applied to the modelCitation15, as well as a range of plausible scenarios around onabotulinumtoxinA administration and the time horizon.

This supports the findings of the original model, which presented a base case ICER of £17,212 per QALY gained for the same patient populationCitation23. However, the revised model uses a more recent source of utility data derived directly from the EQ-5D of the REPOSE observational study, compared with mapping the MSQ of the PREEMPT trial to the EQ-5D in the original model. The REPOSE study directly collected EQ-5D data based on 3,524 observations of patients who received treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA in the real world and avoided the use of a mapping algorithm to generate utility values from HRQoL data. This circumvented the non-monotonicity observed in the original utilities, which was likely caused by the small number of patients in the three or more prior prophylactics subgroup of PREEMPT (HRQoL data were available from 359 patients) and the detection of elements of chronic migraine by the MSQ mapping function (headache frequency, severity, and intensity) that were not captured in the health states of the model (defined by the frequency of headache days only)Citation15. Furthermore, the NICE methods guide (PMG9) indicates a preference for utility values collected directly using the EQ-5DCitation25. The utility values from the REPOSE population provide greater certainty in the deterministic base case ICER of the revised model (£16,306 per QALY gained) and were accepted by the SMC in the resubmission of onabotulinumtoxinA in 2017Citation16. The application of the same utility per health state, irrespective of treatment, in the revised model likely produced a conservative ICER estimate, given the difference in HRQoL between the onabotulinumtoxinA and placebo arms observed in PREEMPT for patients within the same health state ()Citation46.

Scenario analyses were used to assess the impact on the ICER when assumptions around the administration of onabotulinumtoxinA and the time horizon of the model were varied based on real-world evidence. Administration of onabotulinumtoxinA by a specialist nurse as opposed to a neurology consultant was found to be cost-saving, reducing the ICER by £2,474 per QALY from the deterministic base case, and represents a more efficient use of NHS resources. Administration by nurses was accepted by the SMC as the preferred model input in the resubmission of onabotulinumtoxinA in 2016Citation16 and is used by the majority of UK centres treating NHS patients with onabotulinumtoxinA for chronic migraine [personal communication F.A. and B.D.]. The two-year time horizon was extended to three years based on an extrapolation of one-year data from PREEMPT and longer-term real-life observational studies demonstrating the continued effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA beyond one yearCitation32,Citation33,Citation36–40. Combining nurse administration and a three-year time horizon in the model substantially reduced the ICER estimate to £9,801 per QALY gained, well below the cost-effectiveness threshold of NICE.

Positive and negative stopping rules were applied as part of the recommendation for onabotulinumtoxinA in the NICE single technology appraisalCitation15. The negative stopping rule manages withdrawal from onabotulinumtoxinA in patients experiencing insufficient benefit and is feasible to implement in clinical practiceCitation17, although alternative criteria could be considered more clinically relevant (such as the modified Hull criteria which considers headache days, migraine days, and headache-free days to account for severity as well as frequency of headache)Citation31. Withdrawing onabotulinumtoxinA treatment when migraines become episodic in frequency (as per the positive stopping rule) is inherently challenging in practice, given the unwillingness of patients who have responded to onabotulinumtoxinA to discontinue a successful treatment and risk experiencing a return of symptoms, and the difficulties in getting a fast appointment to restart treatment if chronic migraine returnsCitation17. Furthermore, patients with high frequency episodic migraine (10–14 headache days per month) have been shown to have similar emotional and functional disabilities to patients with chronic migraine, and less similarities to patients with low frequency episodic migraine (1–9 headache days per month)Citation47. Therefore, implementing the positive stopping rule as currently defined by NICE is not practical, beneficial to patients, or supported by the characteristics of the diseaseCitation17,Citation47.

Following the publication of the NICE guidance (TA260)Citation15, a modified positive stopping rule has been proposed whereby patients only stop treatment when the number of days of headache are less than 10 days per month for three months (personal communication F.A.Citation36). This modified stopping rule was based on the observation that patients with high-frequency episodic migraine tend to revert to chronic migraine when treatment is stopped but this is not the case for low-frequency episodic migraine (personal communication F.A. and B.D.). The recent EHF guidelines recommend the use of the modified positive stopping rule for managing withdrawal of patients who have responded to onabotulinumtoxinACitation17.

Removal of the positive stopping rule from the NICE appraisal (TA260)Citation15 produced an ICER of £13,245 per QALY gained when combined with nurse administration and a three-year time horizon. The ICER was also cost-effective according to the NICE threshold when removal of the positive stopping rule was combined with either one of these scenarios. Therefore, while important when the preferred base case assumptions of the NICE appraisal committee in 2012 were applied to the model, the positive stopping rule was not necessary for demonstrating the cost-effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA with nurse administration, which reflects current clinical practice. The introduction of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) inhibitors presents an additional challenge in terms of managing the positive stopping rule: were CGRP inhibitors to become a treatment option for patients with episodic migraine then patients entering the episodic migraine health states as a result of onabotulinumtoxinA treatment may progress onto potentially more expensive CGRP inhibitors if the positive stopping rule were applied. Therefore, the application of a positive stopping rule needs to be considered in the context of patient management and efficient use of NHS resources. Future research can further evaluate the impact of modified stopping rules (such as withdrawal of patients with low-frequency episodic migraine) on cost-effectiveness.

As discussed in Batty et al.Citation23, there are limitations of the cost-effectiveness analysis. Firstly, the comparator used in the PREEMPT trial was placebo, which involved saline injections at 12-week intervals. In the model, this was used as a proxy for standard care with acute treatments such as triptans because other preventive treatments are expected to be tried (off-label with the exception of topiramate) as earlier lines of therapy according to NICE clinical guidelinesCitation11. However, the placebo arm of PREEMPT was associated with a reduction in headache days, which may not be achievable with standard care in clinical practice, where saline injections would not be used. Therefore, the ICERs produced by the model are likely to be a conservative estimate of the cost associated with onabotulinumtoxinA compared with standard care. Secondly, the model applies a two-year time horizon and does not consider restarting treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA after discontinuing, which is particularly relevant for discontinuations as a result of the positive stopping rule. In view of this, extending the time horizon beyond two years may produce additional uncertainty in the ICER estimates. Finally, the revised base case of the model assumes that utility is only related to the number of headache days and is not treatment specific. This is a conservative assumption as any benefit of onabotulinumtoxinA beyond its impact on the number of headache days is not captured.

Conclusion

NICE recommended onabotulinumtoxinA for the preventive treatment of chronic migraine in 2012 amid concerns about the uncertainty of ICER estimates provided at the time, with a positive stopping rule used to manage some of these uncertainties. The real-world evidence available since publication of the NICE guidance provides a more recent source of utility data, supports long-term effectiveness beyond the one-year clinical trial, and supports the assumption that onabotulinumtoxinA can be administered by a nurse. As a result, the ICER estimates from the revised economic model provide greater certainty that onabotulinumtoxinA represents a cost-effective treatment for chronic migraine in patients who have previously received three or more prophylactic treatments in the UK. The results of scenario analyses indicate that the application of the positive stopping rule is not necessary to ensure cost-effectiveness and that this aspect of the current NICE guidance for onabotulinumtoxinA may merit reconsideration.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Support for this study was provided by Allergan UK, Marlow, Buckinghamshire, UK.

Declaration of financial/other interests

G.H.H. and A.C. disclose that they are employees of SIRIUS Market Access, a company that received funding from Allergan for its role in developing this manuscript. K.O. is an employee of Allergan. R.A. is chairman of a company which has undertaken paid work for Allergan on treatments for migraine. F.A. declares that he has received honorarium for consultancy and lecturing from Allergan, Eneura, ElectroCore, and Novartis, which is paid to the British Association for the Study of Headache and the Migraine Trust. B.D. declares that he has received honourium for consultancy advice from Allergan, Novartis and Lilly. I.K. was an employee of Allergan at the time the research was conducted and is a stock shareholder of Allergan.

Author contributions

G.H.H. and A.C. were involved in the conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting and revision of the manuscript. K.O. was involved in the analysis and interpretation of data and drafting and reviewing of the manuscript. I.K. and R.A. were involved in interpretation of data and critical reviewing of all drafts of the manuscript for intellectual content. F.A. and B.D. critically reviewed all drafts of the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of this work.

Acknowledgements

No non-author assistance in the preparation of this article is to be declared.

References

- Natoli JL, Manack A, Dean B, et al. Global prevalence of chronic migraine: a systematic review. Cephalalgia. 2010;30(5):599–609.

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(1):1–211.

- Blumenfeld AM, Varon SF, Wilcox TK, et al. Disability, HRQoL and resource use among chronic and episodic migraineurs: results from the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS). Cephalalgia. 2011;31(3):301–315.

- Katsarava Z, Buse DC, Manack AN, et al. Defining the differences between episodic migraine and chronic migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2012;16(1):86–92.

- Adams AM, Serrano D, Buse DC, et al. The impact of chronic migraine: The Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) Study methods and baseline results. Cephalalgia. 2015;35(7):563–578.

- Lipton RB, Manack Adams A, Buse DC, et al. A comparison of the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) study and American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study: demographics and headache-related disability. Headache. 2016;56(8):1280–1289.

- Aurora SK, Brin MF. Chronic migraine: An update on physiology, imaging, and the mechanism of action of two available pharmacologic therapies. Headache. 2017;57(1):109–125.

- BASH. Guidelines for all healthcare professionals in the diagnosis and management of migraine, tension-type, cluster and medication-overuse headache. In: MacGregor E, Steiner T, Davies P, editors. Hull, UK: British Association for the Study of Headache; 2010.

- NICE. Clinical Knowledge Summaries: Migraine London, UK: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2018 [2017 Jun 3]. Available from: https://cks.nice.org.uk/migraine

- NICE. National Instute for Health and Care Excellence Pathways: management of migraine (with or without aura) London, UK; 2017 [2017 Jun 3]. Available from: https://pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/headaches/management-of-migraine-with-or-without-aura

- NICE [CG150]. Headaches in over 12s: diagnosis and management. London, UK: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2012.

- SIGN. Pharmacological management of migraine (155): a national clinical guideline. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network; 2018 [cited 2018 July 4]. Available from: www.sign.ac.uk

- eMC. Summary of Product Characteristics - Topamax 25 mg tablets -. Surrey, UK: electronic Medicines Compendium; 2018 [cited 2018 July 4]. Available from: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc

- eMC. Summary of Product Characteristics - Botox 200 units. Surrey, UK: electronic Medicines Compendium; 2018 [cited 2018 July 4]. Available from: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/

- NICE [TA260]. Botulinum toxin type A for the prevention of headaches in adults with chronic migraine. London, UK: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2012.

- SMC [692/11]. 2nd Resubmission; botulinum toxin A, 50 Allergan units, 100 Allergan units, 200 Allergan units, powder for solution for injection (Botox); SMC No. (692/11). Glasgow, UK: Scottish Medicines Consortium; 2017 [cited 2018 July 4]. Available from: https://www.scottishmedicines.org.uk/

- Bendtsen L, Sacco S, Ashina M, et al. Guideline on the use of OnabotulinumtoxinA in chronic migraine: a consensus statement from the European Headache Federation. J Headache Pain. 2018;19(1):91.

- Aurora SK, Dodick DW, Turkel CC, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase of the PREEMPT 1 trial. Cephalalgia. 2010;30(7):793–803.

- Diener HC, Dodick DW, Aurora SK, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase of the PREEMPT 2 trial. Cephalalgia. 2010;30(7):804–814.

- Aurora SK, Winner P, Freeman MC, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: pooled analyses of the 56-week PREEMPT clinical program. Headache. 2011;51(9):1358–1373.

- Dodick DW, Turkel CC, DeGryse RE, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: pooled results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phases of the PREEMPT clinical program. Headache. 2010;50(6):921–936.

- Jhingran P, Osterhaus JT, Miller DW, et al. Development and validation of the Migraine-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire. Headache. 1998;38(4):295–302.

- Batty AJ, Hansen RN, Bloudek LM, et al. The cost-effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA for the prophylaxis of headache in adults with chronic migraine in the UK. J Med Econ. 2013;16(7):877–887.

- Gillard PJ, Devine B, Varon SF, et al. Mapping from disease-specific measures to health-state utility values in individuals with migraine. Value Health. 2012;15(3):485–494.

- NICE [PMG9]. Guide to the methods of technology assessment. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2013.

- Ahmed F, Gaul C, Garcia-Monco JC, et al. An open-label prospective study of the real-life use of onabotulinumtoxinA for the treatment of chronic migraine: the REPOSE study. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):26.

- Davies B, Gaul C, Martelletti P, et al. Real-life use of onabotulinumtoxinA for symptom relief in patients with chronic migraine: REPOSE study methodology and baseline data. J Headache Pain. 2017;18(1):93.

- Frampton JE, Silberstein S. OnabotulinumtoxinA: a review in the prevention of chronic migraine. Drugs. 2018;78(5):589–600.

- Ahmed F, Zafar HW, Buture A, et al. Does analgesic overuse matter? Response to OnabotulinumtoxinA in patients with chronic migraine with or without medication overuse. SpringerPlus. 2015;4(1):589.

- Dominguez C, Pozo-Rosich P, Torres-Ferrus M, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA in chronic migraine: predictors of response. A prospective multicentre descriptive study. Eur J Neurol. 2018;25(2):411–416.

- Khalil M, Zafar HW, Quarshie V, et al. Prospective analysis of the use of OnabotulinumtoxinA (BOTOX) in the treatment of chronic migraine; real-life data in 254 patients from Hull, U.K. J Headache Pain. 2014;15(1):54.

- Negro A, Curto M, Lionetto L, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA 155 U in medication overuse headache: a two years prospective study. SpringerPlus. 2015;4(1):826.

- Negro A, Curto M, Lionetto L, et al. A two years open-label prospective study of OnabotulinumtoxinA 195 U in medication overuse headache: a real-world experience. J Headache Pain. 2015;17:1.

- Pedraza MI, de la Cruz C, Ruiz M, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA treatment for chronic migraine: experience in 52 patients treated with the PREEMPT paradigm. SpringerPlus. 2015;4(1):176.

- Alpuente A, Gallardo VJ, Torres-Ferrus M, et al. Early efficacy and late gain in chronic and high-frequency episodic migraine with onabotulinumtoxinA. Eur J Neurol. 2019;20.

- Ahmed F, Khalil M, Tanvir T, et al. MTIS 2018 abstracts. MTIS2018-102: long term outcome for OnabotulinumtoxinA therapy in chronic migraine; a two year follow up of 508 patients from the hull migraine clinic. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(1_suppl):1–115.

- Ahmed F, Khalil M, Tanvir T, et al. MTIS 2018 abstracts. MTIS2018-103: five year outcome on 211 patients receiving OnabotulinumtoxinA for chronic migraine; data from hull migraine clinic. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(1_suppl):1–115.

- Andreou AP, Trimboli M, Al-Kaisy A, et al. Prospective real-world analysis of OnabotulinumtoxinA in chronic migraine post-National Institute for Health and Care Excellence UK technology appraisal. Eur J Neurol. 2018;25(8):1069–1e83.

- Cernuda-Morollon E, Ramon C, Larrosa D, et al. Long-term experience with onabotulinumtoxinA in the treatment of chronic migraine: What happens after one year? Cephalalgia. 2015;35(10):864–868.

- Rothrock JF, Andress-Rothrock D, Scanlon C, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for the treatment of chronic migraine: long-term outcome. Headache. 2011;51(Suppl 1):60.

- Office for National Statistics. National life tables: England, 1980–82 to 2014–16. Office for National Statistics; 2017 [cited 2018 July 4]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/

- NICE BNF. Botulinum toxin type A London, UK: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2018 [2018 Jul 4]. Available from: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/botulinum-toxin-type-a.html

- NHS. NHS reference costs 2016-2017: the main schedule London, UK: National Health Service; 2017 [2018 Jul 4]. Available from: https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/reference-costs/

- Curtis L, Burns A. Unit costs of health and social care 2017 University of Kent, Canterbury: Personal Social Services Research Unit; 2017 [cited 2018 July 4]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.22024/UniKent/01.02/65559

- NHS. Prescription cost analysis - England 2017: National Health Service; 2017. [2018 Jul 4]. Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/prescription-cost-analysis/prescription-cost-analysis-england-2017

- Lipton RB, Varon SF, Grosberg B, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA improves quality of life and reduces impact of chronic migraine. Neurology. 2011;77(15):1465–1472.

- Torres-Ferrus M, Quintana M, Fernandez-Morales J, et al. When does chronic migraine strike? A clinical comparison of migraine according to the headache days suffered per month. Cephalalgia. 2017;37(2):104–113.