Abstract

Aims: As the number of cancer patients increases in Japan, and people are living longer with cancer, the need for caregivers of cancer patients is expected to increase substantially. This study intended to reveal the humanistic and economic burden among caregivers of cancer patients, and to compare it with the burden among caregivers of patients with other conditions (other caregivers) and non-caregivers.

Materials and methods: This cross-sectional analysis used data from the Japan National Health and Wellness Survey 2017. Outcome measures included the Short Form 12-item Health Survey for health-related quality of life (HRQoL), EuroQol 5-dimension scale (EQ-5D) for health states utilities, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire for the impact of health on productivity and activity, and indirect costs. Multivariate analysis was used to compare across groups, with adjustment for potential confounding effects.

Results: A total of 251 caregivers of cancer patients, 1,543 other caregivers, and 27,300 non-caregivers were identified. Caregivers of cancer patients (average 48.0 years old) tended to be younger than non-caregivers (51.5) and other caregivers (54.4) and had the highest education level (57.8% completed university education). Fewer non-caregivers had stress-related comorbidities than caregivers. Non-caregivers had significantly higher EQ-5D index scores than caregivers (average 0.81 vs. 0.73 vs. 0.74). Caregivers of cancer patients had significantly lower mental component summary scores than non-caregivers (40.18 vs. 46.70), and the difference indicated a clinically meaningful decrease in HRQoL. Caregivers of cancer patients had significantly higher presenteeism (37.31% vs. 20.43%), total work productivity impairment (38.85% vs. 21.98%), and activity impairment (40.94% vs. 25.78%) than non-caregivers. Additionally, caregivers of cancer patients had significantly higher total indirect costs (36.34% vs. 20.03% of average annual income).

Conclusions: These results have implications for future healthcare planning, suggesting the importance of healthcare systems in Japan to consider the substantial burden borne by caregivers of cancer patients.

Introduction

The morbidity and mortality of cancer have been increasing both in Japan and globallyCitation1,Citation2. The global annual incidence has been projected to substantially increase by 75% from 2008 to 2030, with an estimated number of 22.3 million according to the International Agency for Cancer ResearchCitation3. In Japan, National Cancer Centre announced that the projected cancer incidence for 2018 was 1,013,600, and projected mortality due to cancer was 379,900Citation1. The total cancer mortality has increased steadily in Japan, and Nagao and Tsugane suggested that the observed increase in mortality is connected to the increased lifespan of the Japanese populationCitation2. In 2017 the proportion of the total population that was 65 years and above was record high in Japan; constituting 27.7%Citation4. Furthermore, treatment advances in oncology have led to improved cancer management for patients, resulting in more patients living for longer with cancer. Additionally, recent changes in health care have shifted much of the cancer care from an inpatient to outpatient and home-based settingCitation5. Therefore, the need for informal caregivers (e.g. unpaid voluntary family members and friends) of cancer patients is expected to increase substantially in the future. Informal caregivers of patients with cancer can reduce the burden of disease and improve quality of life of the patients, by providing long-term voluntary care, assisting with activities of daily living and offering cancer-specific care and emotional support for the patients.

Informal caregivers, on the other hand, face substantial difficulties and burden when they provide care to the patients. Many informal caregivers (67% in a US study) have additional responsibilities, including employment obligations, and may be caring for more than one individualCitation5. European studies have shown sizable humanistic burden among cancer-related caregivers, with significant impairment in health-related quality of life (HRQoL), work productivity and activity impairment, healthcare resource use, and stress-related comorbiditiesCitation4,Citation6,Citation7. In the EU National Health and Wellness Survey, caregivers of cancer patients reported significantly greater stress-related comorbidities, worse HRQoL, greater work productivity and activity impairment, and greater cost burden than non-caregiversCitation4.

As caregivers have a central role in caring for patients with cancer, both mentally and physically, there is a need to understand the humanistic and economic burden, to develop supportive interventions, and to reduce the consequences of such a burdenCitation6. Like other countries, caregiver’s burden is likely to negatively impact their quality of life and other health outcomesCitation5,Citation6. Being able to quantify and properly address the caregiver’s burden will result in improvement of the quality of cancer care and reduction in the overall humanistic and economic burden of cancer on the societyCitation5,Citation6.

There is a substantial knowledge gap on the burden of cancer-related caregiving in Japan, with limited research on the effect on caregiver HRQoL, work productivity and activity impairment, stress-related comorbidities, and cost burden. The existing literature on cancer-related caregiving mainly consists of studies performed on populations in the USCitation8–10, EUCitation4,Citation6,Citation7,Citation11 and other countries in AsiaCitation12–14, with a few studies of small sample size conducted in Japan. These studies compared HRQoL of caregivers with national standard valuesCitation15, investigated how bad news and other factors impacted caregivers’ HRQoLCitation16,Citation17, and how different types of family systems influence the degree of psychological stress among caregiversCitation18. One large scale study in Tokyo surveyed cancer patients’ caregivers of which 38.9% reported change in working conditions, including reduced working hours and acquired paid leave, and that 11.4% had quit their jobCitation19. Large scale studies performed in Japan have predominantly focused on caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s or dementia, impaired elderly and how family dynamics are influencedCitation20–23.

It is clear that there is a large unmet need of cancer-related caregiver burden in Japan that needs to be studied to fully understand its impact, and this has become increasingly important considering the growing aging population as well as the expected vast increase in patients living with cancer in the futureCitation24. Furthermore, not only Japan, but also several other western countries are currently facing similar low birth rates, a growing elderly population and increasing incidence of cancer.

The main objective of this study is to describe and quantify the humanistic and economic burden among caregivers who provide care to cancer patients in Japan, and to compare the burden with that of caregivers who provide care to patients with other conditions, and with non-caregivers. In this analysis, the term ‘burden’ refers to the four domains of: (i) self-reported stress-related comorbidities (depression, anxiety, insomnia, headache, migraine, and gastrointestinal problems); (ii) HRQoL; (iii) work productivity and activity impairment; and (iv) indirect costs (absenteeism costs, presenteeism costs, and annual indirect costs). With access to the National Health and Wellness Survey in Japan that provides large-scale population-based data, outcomes from this study will provide valuable insights and enhance the current understanding of cancer-related caregiver burden, while also addressing some of the important gaps in the knowledge base, which need to be addressed for informed decision-making.

Methods

Study design

This cross-sectional analysis used data from the existing database of the Japan National Health and Wellness Survey (NHWS) 2017, an internet-based survey of self-reported patient characteristics and patient outcomes among adults (aged 18 years or older). The survey received Institutional Review Board approval by the Gifu Pharmaceutical University IRB and Pearl Pathways (IRB Study Number: 17-KANT-150) and all respondents provided informed consent prior to participating. Respondents for the Japan NHWS 2017 were recruited by Lightspeed Research (LSR). LSR maintains an existing web-based consumer panel where respondents had consented to join and received periodic invitations to participate in various online surveys. Recruitment for the LSR consumer panel was done via email, e-newsletters, co-registration with other internet panels, and online banner placements. Respondents to the Japan NHWS were recruited by LSR from the existing consumer panel with quotas based on sex and age according to the Census data from Japan Ministry of Internal Affairs & CommunicationsCitation25. Although the stratified sample did not account for other demographic factors such as education, the NHWS is generally comparable to the population with respect to these characteristicsCitation26–28.

The NHWS includes comprehensive data on a number of disease factors, including self-reported experience, diagnosis of the conditions, treatment received, and health-related outcomes. The NHWS also includes information on caregivers of patients of 20 pre-defined conditions including cancer: Alzheimer's disease (35.6% of all caregivers in the 2017 NHWS Japan database), Bipolar disorder (1.4%), Cancer (14.0%), Crohn’s Disease (1.0%), Chronic Kidney disease on dialysis (3.5%), Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) (1.1%), Heart Disease (such as Congestive Heart Failure) (4.2%), Dementia (31.1%), Depression (8.2%), Diabetes (Type I) (4.0%), Epilepsy (2.5%), ITP (platelet disorder) (0.2%), Macular Degeneration (1.1%), Multiple Sclerosis (0.6%), Muscular Dystrophy (0.3%), Osteoarthritis (2.6%), Osteoporosis (9.8%), Parkinson's Disease (5.4%), Schizophrenia (4.5%), Stroke (9.8%), and other conditions (10.2%). Note that caregivers may include individuals taking care of multiple patients with different diseases, or individuals taking care of one patient with more than one of the diseases listed. Hence the sum of percentages listed above exceeds 100%.

Study population

The total number of respondents to the Japan NHWS database 2017 was 30,001. As part of the NHWS, participants were asked if they currently were caring for any adult relatives suffering from the above-listed conditions. Respondents who reported currently caring for an adult with cancer or any other (non-cancer) conditions were included in the caregiver group. Respondents who reported caring for an adult with cancer were included in the cancer caregiver group. Respondents who reported currently caring for an adult with any of the other conditions than cancer as listed above were included in the other caregiver group. Respondents who reported currently not caring for any adult with any condition (non-caregivers) served as the control group.

Measures and survey instruments

Sociodemographic characteristics measured included age, sex, marital status, education, household income, number of adults in household, number of children in household, health insurance, additional health insurance, and employment status. General health characteristics measured included smoking status, exercise behavior, alcohol use, body mass index, taking steps to lose weight, and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)Citation29–31.

Outcome assessment

Self-reported stress-related comorbidities

Depression, anxiety, insomnia, headache, migraine, and gastrointestinal problems were among the list of conditions covered in the NHWS data. Self-reported experience of these stress-related comorbidities was treated as outcomes in this study.

HRQoL

HRQoL was assessed using the physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS) from the Short Form 12-item (version 2) Health Survey (SF-12v2) that has been translated and validated for use in the Japanese populationCitation32,Citation33. SF-12v2 comprises 12 questions that provide a summary scores on eight health domains (physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, emotional role limitations, and mental health); higher scores indicate better quality of life.

Health state utilities were quantified by the EuroQol 5-dimension scale (EQ-5D), which provides a measure of HRQoLCitation34. The EQ-5D Index is derived from the EQ-5D domains of mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. Higher scores indicate better health status.

The work productivity and activity impairment (WPAI)

The WPAI questionnaire was used to measure the impact of health on employment-related and general activitiesCitation35,Citation36. The WPAI is a six-item validated instrument consisting of four domains: absenteeism (work time missed due to one’s health, expressed in % of work time missed in past 7 days), presenteeism (impairment at work/reduced work effectiveness, expressed as % of work impairment experienced while at work in the past 7 days), work productivity loss (overall work impairment/absenteeism plus presenteeism), and activity impairment (impairment in daily activities, expressed as the percentage of impairment in daily activities experienced in the past seven days). WPAI outcomes are expressed as impairment percentages, with higher numbers indicating greater impairment and/or less productivity.

Annual indirect costs

Annual indirect costs were estimated from the NHWS data. Annual indirect costs due to absenteeism and presenteeism were calculated by integrating information from the WPAI and hourly wage rates from the Japan Basic Survey on Wage Structure, 2017Citation37, using the human capital method. For each employed respondent, the hours of work lost due to absenteeism or presenteeism were multiplied by the estimated wage to estimate the total weekly absenteeism costs, presenteeism costs, and indirect costs. These costs were annualized.

Statistical analyses

Caregivers of patients with cancer, caregivers of patients with other conditions, and non-caregivers were compared with respect to demographics and patient health characteristics, healthcare attitudes and opinions, and health outcomes using chi-squared test for categorical variables and one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables. After comparisons had been done overall across the three groups, pairwise comparisons between two groups were conducted.

Generalized linear models (GLMs) were then used to compare health outcomes among the four domains between caregivers and non-caregivers, accounting for demographic and clinical characteristics of the respondents. Demographic and clinical characteristics that were significantly different among caregivers of patients with cancer, caregivers of patients with other conditions, and non-caregivers, in addition to variables of theoretical significance would be used as covariates for the GLMs. Normal distribution with identity link was specified in the GLMs for normally distributed outcomes including MCS, PCS and EQ-5D. Negative binomial distribution with log link was specified for outcomes with skewed distributions, i.e. WPAI-related health outcomes and indirect costs. Binomial distribution with logistic link was specified for self-reported stress-related comorbidities. Estimated adjusted means, standard errors, confidence intervals, and p-values were reported for each predictor group for each health outcome. All outcome variables were pre-determined before the analyses and the analyses were not of exploratory manner. No correction for multiple testing was conducted for this study. For all analyses, statistical significance was assessed at a significance level of .05. All data analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 22Citation38.

Results

Participants

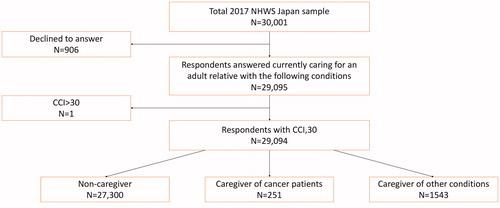

A total of 251 respondents who provide care to patients with cancer, 1,543 respondents who provide care to patients with other (non-cancer) conditions, and 27,300 non-caregivers were identified from the Japan NHWS database 2017 (). 906 respondents declined to answer the question about caregiving status and one respondent was excluded due to high CCI score.

Figure 1. Respondent flow diagram. Abbreviations. CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; NHWS, National Health and Wellness Survey.

Caregivers of cancer patients tended to be younger (Mean [Standard deviation] = 49.0 [17.0] years old) than non-caregivers (M[SD] = 51.5[6.5]) and other caregivers tended to be the oldest (M[SD] = 54.5[15.6]). Caregivers of cancer patients had the highest education level (57.8% completed university education vs. 48.5% of non-caregivers and 48.3% of other caregivers). Caregivers of cancer patients had the highest employment rate (59.0% vs. 55.5% of non-caregivers and 52.9% of other caregivers) ().

Table 1. Sociodemographic and health characteristics as a function of caregiver status (without adjustment).

Non-caregivers had the lowest CCI (M[SD] = 0.16[0.48]), which was significantly lower than that of caregivers of cancer patients who had the highest CCI (M[SD] = 0.47[1.94]) and caregivers of patients with other conditions (M[SD] = 0.30[0.73]). More caregivers of cancer patients were current smokers (29.5%) than caregivers of other conditions (21.4%) or non-caregivers (18.4%) and more caregivers exercised regularly (52.6% of caregivers of cancer patients and 48.9% of caregivers of other conditions) than non-caregivers (44.8%). Also, more caregivers (33.5% and 26.1%) were trying to lose weight than non-caregivers (20.4%).

Overall, differences in general healthcare attitudes were observed between caregivers (both groups) and non-caregivers, but not between caregivers of cancer patients and caregivers of other conditions. For health insurance, no significant differences were observed between non-caregivers and caregivers of cancer patients, and between caregivers of cancer patients and caregivers of other conditions. More caregivers of cancer patients had additional cancer insurance (49.8% vs. 30.7% of non-caregivers and 34.2% of other caregivers) and additional severe disease insurance (18.3% vs. 6.5% of non-caregivers and 10.2% of other caregivers) than the other two groups. Both groups of caregivers tended to have more additional insurance coverage than non-caregivers.

Based on these baseline comparisons, age, gender, marital status, level of education, household income, number of adults in the household, number of children in the household, employment status, CCI, BMI, smoking status, alcohol use, vigorous exercise in past 30 days, and currently taking steps to lose weight were included in the GLMs as covariates to understand the difference in humanistic burden after adjustment.

Stress comorbidities

The stress-related comorbidities analyzed in this study were depression, anxiety, insomnia, headache, migraine, and gastrointestinal problems (gastroesophageal reflux disease, heartburn, and/or irritable bowel syndrome). Without adjustment, a significantly lower proportion of non-caregivers had all types of stress-related comorbidities compared with caregivers in both groups (p < .001) (Supplementary Table S1). Caregivers of cancer patients had a significantly higher proportion of all stress-related comorbidities, except depression, than did caregivers of other conditions (p < .001).

After adjustment for potential confounding effects of demographic and clinical characteristics, there were no significant differences between caregivers of cancer patients and caregivers of other conditions, except for gastrointestinal problems (). Caregivers of cancer patients had significantly increased odds of gastrointestinal problems compared with caregivers of other conditions (p = .001). Significant differences were found between non-caregivers and both caregiver groups for all stress-related comorbidities.

Table 2. Adjusted odds ratios for stress-related comorbidities after controlling for demographics and clinical variables among respondents.

HRQoL

Without adjustment, non-caregivers had significantly higher MCS and PCS scores than caregivers of cancer patients and caregivers of other conditions (Supplementary Table S2). The same result was observed for all eight subcomponents (physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role emotional, and mental health) of the SF-12v2. Non-caregivers had higher EQ-5D index compared with caregivers in both groups. Caregivers of cancer patients had significantly lower scores than caregivers of other conditions for MCS, role physical, vitality, social functioning, role emotional, mental health, and EQ-5D index.

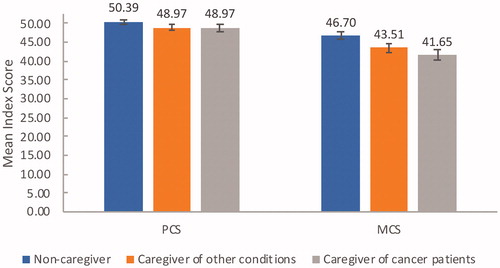

After adjusting for potential confounding effects of demographics and clinical characteristics, similar results were obtained. Non-caregivers had significantly higher MCS, PCS, and EQ-5D index than caregivers (; ). Caregivers of cancer patients had significantly lower MCS than caregivers of other conditions. Compared to non-caregivers, the deterioration in MCS score among caregivers was greater than 3 (3.19 and 5.04 for caregivers of other conditions and caregivers of cancer patients, respectively), which represented a clinically meaningful decrease in HRQoL ().

Figure 2. Comparison of health-related quality of life. Adjusted means of PCS and MCS scores after adjusting for potential confounders. Abbreviations. MCS, mental component summary; PCS, physical component summary.

Table 3. Adjusted means (95% CIs) for health-related quality of life outcomes after controlling for demographics and clinical variables among respondents.

Table 4. Adjusted health-related quality of life as a function of caregiving and regression coefficients, after controlling for covariates.

Work productivity and activity impairment

Without adjustment, caregivers had greater impairment in both total work productivity and activity than non-caregivers (Supplementary Table S3). Non-caregivers had the least activity impairment (20.2%) and caregivers of cancer patients had the greatest impairment (33.8%). For work productivity impairment, non-caregivers had the lowest absenteeism compared with caregivers of cancer patients and caregivers of other conditions (2.4% vs. 8.9% and 7.0%, respectively), presenteeism (19.4% vs. 38.5% and 29.2%, respectively), and total work productivity impairment (20.2% vs. 40.4% and 31.8%, respectively). Caregivers of cancer patients had significantly higher impairment than caregivers of other conditions in terms of presenteeism (p = .004), total work productivity (p = .014), and activity impairment (p = .006).

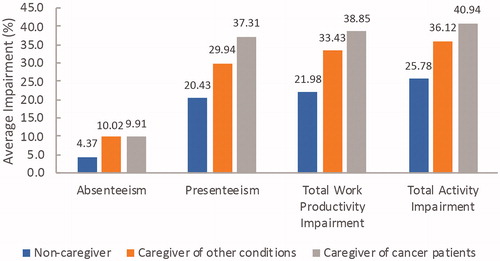

After adjusting for potential confounding effects of demographics and clinical characteristics, caregivers were also found to have significantly higher presenteeism, total work productivity impairment, and activity impairment than non-caregivers (; ). Caregivers of cancer patients had the highest impacted presenteeism, total work productivity impairment and total activity impairment. Compared to non-caregivers, presenteeism and total work productivity impairment were 17% increased (37% vs. 20% and 39% vs. 22%), and total activity impairment was increased with 15% (41% vs. 26%).

Figure 3. Comparison of Work Productivity and Activity Impairment. Adjusted means of WPAI, after adjusting for potential confounders. Abbreviations. WPAI, Work productivity and activity impairment.

Table 5. Adjusted means (95% CIs) for work productivity and activity impairment outcomes after controlling for demographics and clinical variables among respondents.

Annual indirect costs

Without adjustment, non-caregivers were estimated to incur significantly less indirect costs (based on age and gender stratified wage of 2017) than caregivers in both groups (Supplementary Table S4). No significant differences in absenteeism cost and indirect cost were observed between caregivers of cancer patients and caregivers of other conditions.

There were no differences between caregivers of cancer patients and caregivers of other conditions ().

Table 6. Adjusted means (95% CIs) for indirect costs outcomes (as a percentage of average annual income) after controlling for demographics and clinical variables among respondents.

Discussion

Results from this study showed that caregivers of patients with cancer in Japan were considerably impacted by their caregiving role when compared with non-caregivers, with cancer caregivers having significantly worse HRQoL, greater work productivity and activity impairment, higher indirect costs and more stress-related comorbidities which included higher odds of depression, anxiety, insomnia, headache, migraine, and gastrointestinal problems than non-caregivers.

To our knowledge, this is the first large scale study of the Japanese population comparing the burden of caregivers of patients with cancer to that of non-caregivers and caregivers of other conditions. Additionally, to our knowledge, this is the first study describing the work productivity and activity impairment for caregivers of patients with cancer in Japan.

Our study found that caregivers of cancer patients in Japan reported significantly greater stress-related comorbidities (depression, anxiety, insomnia, headache, migraine, and gastrointestinal problems) (), worse HRQoL ( and ), higher overall work productivity and activity impairment (), and greater costs () than non-caregivers. These results were consistent with other global studies on the humanistic and economic burden of caregiving for cancer patients. Two European studies from the 2010/2011 EU NHWS assessing the burden of informal caregiving for patients with cancer found that respondents had significant impairment for all health measures compared with non-caregivers, including greater stress-related comorbidity, worse HRQoL, greater work productivity and activity impairment, and higher annual costsCitation4,Citation6. Our findings that cancer caregivers had significantly greater work productivity and activity impartment compared to non-caregivers (38.9% for caregivers of cancer patients, vs. 22.0% for non-caregivers, ), was further supported by a recent European study where caregivers of patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer reported a high overall work impairment ranging from 21.1% in Germany to 30.4% in FranceCitation7.

Another NHWS-based caregiver study in Japan used data from 2012-2013 to investigate the burden of caregivers for patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or dementiaCitation20. Similarly to the findings in this study, an increased burden in terms of HRQoL and WPAI was found among caregivers compared to non-caregivers. However, the differences in PCS and MCS between caregivers of AD or dementia and non-caregivers were less than 3 and hence not clinically significant (PCS: 51.60 vs. 52.73, MCS: 46.00 vs. 48.60). This stands in contrast to the clinically significant difference in PCS and MSC between caregivers of cancer patients and non-caregivers observed in this study. Furthermore, compared to the respective non-caregiver groups, the increased WPAI for caregivers of cancer is much larger (15.2% total activity impairment, 16.9% presenteeism and total work impairment respectively) than the difference observed in caregivers of patients with AD or dementia (differences: 3.6% total activity impairment; 4.3% presenteeism and 5.4% total work impairment). This indicates that caregivers of cancer patients face a higher burden than caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s and dementia, although the limitations in direct comparison to the study by Goren et al. should be recognized.

In this study, we also compared caregivers of cancer patients with caregivers of other conditions and found that caregivers of other conditions had a similarly worsened HRQoL, compared to non-caregivers ( and ). Although not statistically significant, we observed a high numerical difference in work productivity and activity impairment for caregivers of cancer patients vs. caregivers of other conditions for presenteeism (37.3% vs. 30.0%, difference 7.3%), total work productivity impairment (38.9% vs. 33.4%, difference 5.5%) and total activity impairment (41.0% vs. 36.1%, difference 4.9%) (). These results thereby indicated that caregivers for cancer patients may experience a greater impact on their work life than caregivers of other conditions which is critical to consider for an aging society.

A study by Mazanec et al. described the health promotion behaviors and work productivity loss in informal caregivers of patients with advanced cancer in the US because some US caregivers reported that caregiving responsibilities caused them to delay their own medical consultations and reduced their rest timeCitation8. Although the survey in this study for Japan did not address caregiver’s delays in own medical consultations, we regarded that our findings of significantly increased stress-related comorbidities could be reflected by the caregiver's neglect on their own health due to caregiving responsibilities.

This study found that costs related to absenteeism, presenteeism, and indirect costs were significantly higher among caregivers (). A study in Japan examining the economic burden of cancer treatment on patients and their caregivers found that factors associated with work productivity loss among caregivers included treatment intensity, travel for treatment, and time spent on treatment-related activities necessitating altered working hoursCitation39. The need for informal caregivers in these situations that causes absence from work could be mitigated by initiatives for improved nursing care providing better support for patients during treatment administration, and innovative healthcare service offerings, for example, patient transport service to the site of treatment. In January 2017, an amendment to the law concerning the welfare of workers took effect allowing up to 93 days of paid caregiver leave and the right to more flexible hoursCitation40,Citation41. With time, this law can hopefully increase employers support for caregivers and minimize the work productivity impairment. The full effect of this policy on the burden of caregivers will be interesting to follow in the future, as it might not be fully reflected in the data collected in 2017 for this study.

Several other studies have investigated methods to reduce caregiver burden. As informal caregivers are usually untrained and unpaid, despite caring for patients with often severe illnessesCitation5, supportive care programs and caregiver education could help improve HRQoL of caregivers and lessen the burden of stress-related comorbidities, as well as improve the quality of care for the patient. Among caregivers of elderly patients in Japan, informal support from family members has been shown to reduce the caregiver burdenCitation42. Among caregivers of patients with cerebrovascular disease, use of care services, reduction of care time, and increase of caregivers’ free time helped to decrease caregiver burdenCitation43.

The public Long-term Care Insurance System in Japan has also been shown to reduce the burden of caregiving in JapanCitation44. Despite the existing research of initiatives that have proved to reduce caregiver burden, our findings show that a humanistic and economic burden still exists among caregivers for both cancer patients and patients with other conditions. From the demographics of our study, caregivers of cancer patients were significantly more likely to be women (), this reflected the social convention that women may have greater caring responsibilities within the home. A similar overrepresentation of women among caregivers was found in US and EU studiesCitation5,Citation6. Additionally, caregivers of cancer patients were significantly younger than non-caregivers and caregivers of patients with other conditions, with a mean age of 48 years (). People of this age are in the active working force. Because of such sociodemographic characteristics, we believe that the burden of caregivers, especially for cancer patients, is a social issue to be addressed. Further research is needed to discover additional initiatives and/or ways to implement those methods already suggested in existing research as mentioned previously in this discussion, to reduce the burden for caregivers. Furthermore, the growing elderly population in Japan and the expected increase in need for informal caregivers underlines the importance of addressing the humanistic and economic burden of caregivers. The results of this study may also be relevant to other countries struggling with a similar aging population or are facing this issue in the future based on projected increase in population and cancer incidence. Insights from this study performed in Japan may, therefore, give an indication of what is waiting ahead and an opportunity to consider taking preventive actions based on this knowledge.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. The NHWS data are cross-sectional and causal relationships between caregiver status and health outcomes cannot be assumed. All data are self-reported, so no verification of caregiver status or burden can be conducted. This study is limited to the data collected in the NHWS. Information on the disease severity of the patients being cared for is not available, nor is a comprehensive listing of comorbiditiesCitation45.

Also, the limitations in the cost analysis should be recognized. The analysis focused on the costs of unpaid informal care calculated based on the hours of lost work (WPAI) and wage rates from the Japan Basic Survey on Wage Structure (also called an opportunity cost approach)Citation45, wherefore the costs for unemployed informal caregivers and any additional replacement costs were not considered. Due to the design of the survey and available data, the hours for replacement caregiving could not be estimated. These costs could be included in future studies by use of a replacement cost approach as suggested by Wimo et al.Citation45, which could result in an increased informal care cost. However, quantifying caregiver time is a prerequisite for such analysis which is problematic and challenging since definitions and measures of time for informal caregiving vary across different surveysCitation46.

Although the NHWS is broadly representative of the Japanese adult population, the extent to which caregivers of cancer patients and caregivers of other conditions are representative of the larger population is unclear. The NWHS primarily relies upon respondents with Internet access and these patients could potentially be different from the broader population (more knowledgeable or engaged in their healthcare).

Patient factors that might have influenced the results include disease progression and severity, cognitive and neurological impairments, poor physical and psychological status, and receipt of chemotherapy. Factors influencing caregiver results include intensive cancer treatment, travel for patient treatment, time due to treatment adverse effects, and change in work hours during treatment. These are important as unadjusted confounders.

The current study focused on evaluating the difference between the caregivers and non-caregivers in terms of the health outcomes, it is not clear, however, among the caregivers of patients with cancer, the demographic and general health characteristics that might be associated with higher humanistic burden. This would be an avenue for future work.

Conclusion

The results from our study showed that sizable humanistic and economic burden exists among caregivers of patients with cancer in Japan. It has implications for future healthcare planning, suggesting the importance for healthcare systems in Japan to consider the substantial burden borne by the caregivers of patients with cancer. This might help the construction of social support for caregivers who are caring for patients with cancer. In addition, the results of this study may prove helpful for the countries facing a similar rapidly growing aging population as in Japan.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan.

Declaration of financial/other interests

Shinya Ohno is an employee of Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan. Yirong Chen is an employee of Kantar Health Singapore. Hiroyuki Sakamaki have received honoraria from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan. Katsura Tsukamoto and Naoki Matsumaru declares no conflict of interest.

JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work, but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

SO, YC, HS, NM, and KT conceptualized the study. SO and YC conducted the statistical analysis. HS, NM, and KT advised and reviewed the analysis. All authors wrote and reviewed the final manuscript.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Gifu Pharmaceutical University IRB (30-16): and Pearl Pathways (IRB Study Number: 17-KANT-150).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (32 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Takuya Hano, Motoaki Yoshino, Norifumi Shuto and Kinuyo Churei at the Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., LTD, Tokyo, Japan. The authors thank Mary Smith and McCann Health Singapore, and Dina Graae Kristensen at Kantar, Health Division, Singapore, for providing medical writing support and editorial support, which was funded by Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (http://www.ismpp.org/gpp3).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, SO, upon reasonable request.

References

- Cancer information Service, National Cancer Center Japan. Projected Cancer Statistics, 2018. [Internet]. [cited 2019 May 6]. Available from: https://ganjoho.jp/en/public/statistics/short_pred.html.

- Nagao M, Tsugane S. Cancer in Japan: prevalence, prevention and the role of heterocyclic amines in human carcinogenesis. Genes Environ. 2016;38:16.

- Bray F, Jemal A, Grey N, et al. Global cancer transitions according to the Human Development Index (2008–2030): a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(8):790–801.

- Jassem J, Penrod JR, Goren A, et al. Caring for relatives with lung cancer in Europe: an evaluation of caregivers’ experience. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(12):2843–2852.

- van Ryn M, Sanders S, Kahn K, et al. Objective burden, resources, and other stressors among informal cancer caregivers: a hidden quality issue? Psychooncology. 2011;20(1):44–52.

- Goren A, Gilloteau I, Lees M, et al. Quantifying the burden of informal caregiving for patients with cancer in Europe. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(6):1637–1646.

- Wood R, Taylor-Stokes G, Lees M. The humanistic burden associated with caring for patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in three European countries-a real-world survey of caregivers. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(5):1709–1719.

- Mazanec SR, Daly BJ, Douglas SL, et al. Work productivity and health of informal caregivers of persons with advanced cancer. Res Nurs Health. 2011;34(6):483–495.

- Kamal KM, Covvey JR, Dashputre A, et al. A systematic review of the effect of cancer treatment on work productivity of patients and caregivers. JMCP. 2017;23:136–162.

- Wan Y, Gao X, Mehta S, et al. Indirect costs associated with metastatic breast cancer. J Med Econ. 2013;16(10):1169–1178.

- Angioli R, Capriglione S, Aloisi A, et al. Economic impact among family caregivers of patients with advanced ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2015;25(8):1541–1546.

- Lim HA, Tan JY, Chua J, et al. Quality of life of family caregivers of cancer patients in Singapore and globally. Singapore Med J. 2017;58(5):258–261.

- Abdullah NN, Idris IB, Shamsuddin K, et al. Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL) of gastrointestinal cancer caregivers: the impact of caregiving. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2019;20(4):1191–1197.

- Kim H, Yi M. Unmet needs and quality of life of family caregivers of cancer patients in South Korea. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2015;2:152–159.

- Miyashita M, Misawa T, Abe M, et al. Quality of life, day hospice needs, and satisfaction of community-dwelling patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers in Japan. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(9):1203–1207.

- Ito E, Tadaka E. Quality of life among the family caregivers of patients with terminal cancer at home in Japan. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2017;14(4):341–352.

- Kugimoto T, Katsuki R, Kosugi T, et al. Significance of psychological stress response and health-related quality of life in spouses of cancer patients when given bad news. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2017;4:147–154.

- Segawa Y, Noguchi T. Relationship between the family system of a family with terminal patients and the stress of the primary caregiver [Article in Japanese]. Fam Nursing Res. 2004;9:106–112.

- Bureau of Social Welfare and Public Health. Fact-finding survey on employment of cancer patients [Article in Japanese]. [cited May 2014]. Tokyo, Japan. Available from: http://www.fukushihoken.metro.tokyo.jp/iryo/iryo_hoken/gan_portal/soudan/ryouritsu/other/houkoku.htm. Accessed 2 September 2019.

- Goren A, Montgomery W, Kahle-Wrobleski K, et al. Impact of caring for persons with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia on caregivers’ health outcomes: findings from a community based survey in Japan. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16(1):122.

- Fujihara S, Inoue A, Kubota K, et al. Caregiver burden and work productivity among Japanese working family caregivers of people with dementia. IntJ Behav Med. 2019;26(2):125–135.

- Hirakawa Y, Kuzuya M, Enoki H, et al. Caregiver burden among Japanese informal caregivers of cognitively impaired elderly in community settings. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2008;46(3):367–374.

- Kusaba T, Sato K, Fukuma S, et al. Influence of family dynamics on burden among family caregivers in aging Japan. FAMPRJ. 2016;33(5):466–470.

- Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Statistical Handbook of Japan [Internet]. [cited 2019 May 5]. Available from: https://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/handbook/index.html.

- US Census Bureau DIS. International Programs, International Data Base [Internet]. [cited 2019 May 5]. Available from: https://www.census.gov/data-tools/demo/idb/informationGateway.php.

- Bolge SC, Doan JF, Kannan H, et al. Association of insomnia with quality of life, work productivity, and activity impairment. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(4):415.

- DiBonaventura MD, Wagner J-S, Yuan Y, et al. Humanistic and economic impacts of hepatitis C infection in the United States. J Med Econ. 2010;13(4):709–718.

- Finkelstein EA, Allaire BT, DiBonaventura MD, et al. Direct and indirect costs and potential cost savings of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding among obese patients with diabetes. J Occup Environ Med. 2011;53(9):1025–1029.

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383.

- Charlson ME, Charlson RE, Peterson JC, et al. The Charlson comorbidity index is adapted to predict costs of chronic disease in primary care patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(12):1234–1240.

- Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(6):676–682.

- Fukuhara S, Bito S, Green J, et al. Translation, adaptation, and validation of the SF-36 Health Survey for use in Japan. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(11):1037–1044.

- Fukuhara S, Ware JE, Kosinski M, et al. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity of the Japanese SF-36 Health Survey. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(11):1045–1053.

- EuroQol Group. EuroQol–a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208.

- Reilly MC, Gooch KL, Wong RL, et al. Validity, reliability and responsiveness of the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire in ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010;49(4):812–819.

- Reilly MC, Bracco A, Ricci J-F, et al. The validity and accuracy of the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire–irritable bowel syndrome version (WPAI:IBS). Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(4):459–467.

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Basic Survey on Wage Structure [Internet]. Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/database/db-l/wage-structure.html.

- IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. IBM Corp; 2013.

- Yamauchi H, Nakagawa C, Fukuda T. Social impacts of the work loss in cancer survivors. Breast Cancer. 2017;24(5):694–701.

- Ueda J, Kamiya S, Mori A, et al. Japan: Important changes to family-related leave in Japan. November 2016. [cited 2019 Sep 2]. Available from: https://www.taylorvinters.com/news/japan-important-changes-family-related-leave-japan.

- Outline of the Act on Childcare Leave, Caregiver Leave, and Other Measures for the Welfare of Workers Caring for Children or Other Family Members. [cited 2019 Sep 2]. Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/policy/children/work-family/dl/190410-01e.pdf

- Shiba K, Kondo N, Kondo K. Informal and formal social support and caregiver burden: The AGES Caregiver Survey. J Epidemiol. 2016;26(12):622–628.

- Watanabe A, Fukuda M, Suzuki M, et al. Factors decreasing caregiver burden to allow patients with cerebrovascular disease to continue in long-term home care. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;24(2):424–430.

- Umegaki H, Yanagawa M, Nonogaki Z, et al. Burden reduction of caregivers for users of care services provided by the public long-term care insurance system in Japan. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;58(1):130–133.

- Wimo A, Jönsson L, Bond J, et al. Alzheimer Disease International. The worldwide economic impact of dementia 2010. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(1):1–11.

- Chari AV, Engberg J, Ray KN, et al. The opportunity costs of informal elder-care in the United States: new estimates from the American Time Use Survey. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(3):871–882.