Abstract

Aims: Various drugs have recently been launched for the treatment of multiple myeloma (MM). This increase in the number of treatment options has potentially changed treatment patterns and medical costs for patients with MM. Japanese public health insurance claims were analyzed to examine the change in the treatment patterns of MM drugs and medical costs per patient.

Materials and methods: A claims database provided by Medical Data Vision was used, which includes data from ∼20 million patients from >300 acute care hospitals across Japan. The type of MM drugs prescribed and medical costs for patients with MM between April 2008 and December 2016 were examined using monthly cross-sectional analyses. Patients with an International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis code of C90.0 were classified as having MM. MM drugs were defined by generic names.

Results: In total, 19,137 patients with MM (average age at first diagnosis: 69.6 years; percentage of women: 47.9%) were identified from the database. The percentage of patients prescribed each MM drug changed substantially as novel drugs were launched. Total medical costs increased until 2010, then stabilized. MM drug costs increased from approximately 2010, but costs for other care decreased, particularly for hospitalization (including surgery).

Limitations: The database contained data from large, acute care hospitals, which may have caused bias in terms of patients’ clinical history and disease severity.

Conclusions: Total medical costs for MM have remained stable since 2010. MM drug costs increased, but costs for other care decreased after the launch of lenalidomide in 2010 and other drugs in 2015 and later. More detailed research is required to confirm whether the launch of novel drugs caused the changes in medical costs.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a hematologic malignancy associated with significant morbidity. MM is characterized by hyperproliferation of malignant plasma cells in bone marrow and immune dysfunction. It is considered a rare disease—in Japan, the 2016 prevalence of MM was estimated at 5.3 per 100,000 personsCitation1. The prevalence rate rises with age, with a mean age of 67 years at diagnosisCitation2.

In general, treatment for MM is not initiated for pre-cancerous conditions, such as monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and smoldering MM, but is generally commenced only when the disease becomes symptomaticCitation3. Although MM is not yet curable, longer survival can be expected with treatment. The treatment strategy for patients with newly-diagnosed MM (NDMM) is dependent on patient characteristics which determine whether patients are eligible for autologous stem cell transplantation after induction chemotherapyCitation4. The clinical guidelines of the Japanese Society of Hematology (JSH) recommend transplantation for patients who maintain major organ function and are aged <65 years, whereas patients who are aged ≥65 years have organ dysfunction, or show other risk factors associated with immune system rejection of transplantation, are generally considered transplant-ineligibleCitation5. Multiple regimens are available for both transplant-eligible and transplant-ineligible patients and include chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and supportive careCitation4.

Recently, a variety of novel drugs have been developed for treatment of MM. Bortezomib, a proteasome inhibitor, and lenalidomide, an immunomodulatory agent, prolonged progression-free survival and overall survival compared with existing standard treatment in randomized phase 3 trials for patients with relapsed/refractory MM (RRMM)Citation6–8 and for patients with NDMMCitation9,Citation10. An analysis using real-world data from the USA indicated that the number of patients using novel MM drugs—bortezomib, lenalidomide, carfilzomib, panobinostat, pomalidomide, and thalidomide—had increased from 8.7% in 2000 to 61.3% in 2014, with corresponding improvements in survival ratesCitation11. In that study, medical costs had increased since 2000; however, the increase in MM drug costs was limited and only accounted for 10.6–28.5% of the overall treatment cost.

Several MM drugs have also been launched in Japan: bortezomib in December 2006, thalidomide in February 2009, lenalidomide in July 2010, pomalidomide in May 2015, panobinostat in August 2015, carfilzomib in August 2016, elotuzumab in November 2016, ixazomib in May 2017, and daratumumab in November 2017. In addition, extremely expensive anticancer drugs, such as nivolumab, have been approved and launched for other malignancies, resulting in discussions about the cost-effectiveness of cancer treatment in JapanCitation12. Considering the recent increase in the number of treatment options for MM, as well as concerns about the rising costs of cancer treatment, a comprehensive analysis of the treatment patterns and medical costs for MM is needed. Only a few studies looking at the medical costs of MM treatment have been conducted in Japan. These studies included a systematic review of treatment costs for RRMMCitation13 and an analysis of the determinants of physicians’ preferences for first-line MM therapyCitation14. To the best of our knowledge, a comprehensive report on the treatment patterns and cost of MM-related care in Japan across NDMM and RRMM has not been published. The present study used a health insurance claims database to examine current treatment patterns of each MM drug and medical costs per patient with MM in Japan between April 2008 and December 2016.

Methods

Study design and data source

The database for this claims-based observational study was provided by Medical Data Vision (Tokyo, Japan). The database contained data collected between April 2008 and July 2017 from acute care hospitals that apply the Japanese Diagnosis and Procedure Combination (DPC) per diem bundle payment system (DPC hospitals). The database covered a cumulative number of ∼20 million patients from >300 DPC hospitals across the country.

Definitions and analyses

The type of MM drugs prescribed and medical costs for patients with MM were analyzed using monthly cross-sectional analyses. The number of patients prescribed each MM drug was calculated on a monthly basis and the percentages of patients treated with any MM drug, or with a novel MM drug, were reported.

Patients with MM were defined as those who had at least one claim coded as MM, C90.0, by the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10)Citation15. This cohort therefore included both patients with NDMM and patients with RRMM.

MM drugs were defined as those that have been approved for treatment of MM in Japan, based on generic names. The 17 drugs included were dexamethasone, prednisolone, bortezomib, melphalan, lenalidomide, cyclophosphamide, thalidomide, vincristine, doxorubicin, pomalidomide, etoposide, ranimustine, cisplatin, cytarabine, panobinostat, cytarabine ocfosfate, and carfilzomib. Of these 17 MM drugs, six were classified as novel MM drugs: thalidomide, bortezomib, lenalidomide, pomalidomide, panobinostat, and carfilzomib.

The observation period for each patient was defined as the time between the earliest and the most recent medical claim for any disease.

The study period was defined as the time between April 2008 and December 2016, allowing a runout period of 7 months. As the database only includes hospital records and not all patients visit the hospital every month, the number of patients included decreased in later months even if patients continued treatment. Since this decrease was observed starting in January 2017, data were analyzed until December 2016.

The cost per patient per month (PPPM) was calculated as the total cost divided by the number of patients in each month. PPPM cost for total medical costs, MM drug costs, non-MM drug medical costs, and other care costs were analyzed. The other care costs were further divided into four sub-categories based on Japanese procedure identification codes: treatment (prescriptions and injections other than MM drugs), hospitalization (hospitalization, anesthesia, and surgery), examination (imaging and testing/histopathological examination), and other. PPPM costs were analyzed for all patients with MM, and also grouped based on an age threshold of 65 years. Nominal fee schedule values in each year were used to calculate the medical costs. Costs were calculated in Japanese yen (JPY), and converted to United States dollars (USD) using the April 2019 exchange rate of 1 USD = 110.00 JPY.

Excel 2010 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) and SAS V.9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) were used for the analyses.

Results

Patient demographics

The database included 19,137 patients with MM. The average age at first diagnosis was 69.6 years, and 47.9% of patients were female. In both genders, the age group of 70–79 years accounted for the greatest proportion of first diagnoses, followed by 60–69 years and 80–89 years.

MM drug treatment patterns

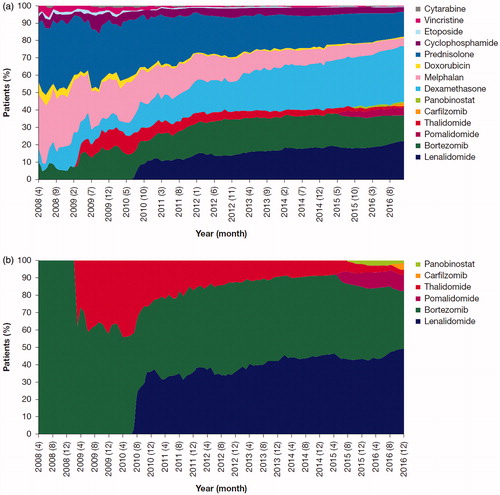

The month-by-month distribution of MM drug prescriptions is shown in . At the end of the study period, dexamethasone and lenalidomide were the first and second most frequently prescribed MM drugs, respectively. The percentage of patients prescribed these two drugs continued to increase during the entire study period. A continuous decrease was seen in the percentage of patients with prescriptions for melphalan and prednisolone, which were, respectively, the first and second most frequently prescribed drugs at the beginning of the study period.

Figure 1. Percentage of patients prescribed each MM drug by month (April 2008–December 2016), for (a) all MM drugs and (b) six novel MM drugs. Abbreviation. MM, multiple myeloma.

Each novel MM drug accounted for some proportion of prescriptions immediately after being launched (. This was accompanied by a decrease in the percentage of patients with prescriptions for the other novel drugs (. In particular, the percentage of patients prescribed thalidomide decreased greatly over time; this decrease started ∼1 year after its launch. Similarly, the percentage of patients prescribed bortezomib decreased from May 2015 (∼8.5 years after its launch), while the percentage of patients with prescriptions for the newly-launched drugs pomalidomide, panobinostat, and carfilzomib increased. The use of lenalidomide did not change substantially over the time period after its launch in July 2010 (.

Medical costs for patients with MM

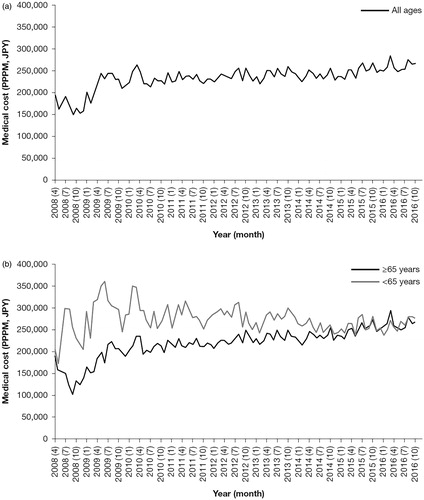

shows the total medical costs PPPM over time. The cost increased to ∼ JPY 250,000 (USD 2,273) in 2010 and remained relatively stable thereafter. For patients aged <65 years, the total medical costs tended to increase, exceeding JPY 300,000 (USD 2,727) in 2009, and then tended to decrease from around 2010 (. In contrast, for those aged ≥65 years, the total medical costs rapidly increased, exceeding JPY 200,000 (USD 1,818) by 2010, and then increased more slowly to ∼ JPY 250,000 (USD 2,273) by 2016 (. Prior to 2015, the cost for patients aged <65 years was higher than for those aged ≥65 years, but almost no differences between the age categories were observed after that year.

Figure 2. Total medical costs PPPM (April 2008–December 2016), for (a) patients of all ages and (b) patients aged <65 and ≥65 years. Abbreviations. JPY, Japanese yen; PPPM, per patient per month.

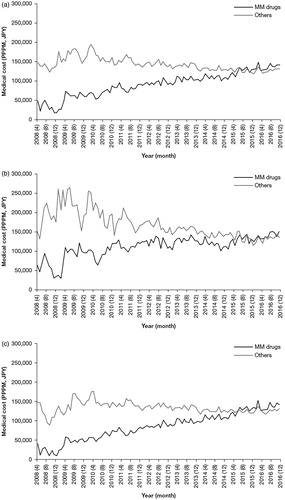

The PPPM costs for MM drugs continued to increase after 2010, from ∼ JPY 50,000 (USD 455) to > JPY 100,000 (USD 909) by 2016 (. The increase in the costs of MM drugs was seen in both age groups, <65 years and ≥65 years (. The costs of non-MM drug medical costs were higher than those of MM drugs until the middle of 2015, after which both costs became similar (.

Figure 3. Medical costs PPPM for MM drugs and other medical costs (April 2008–December 2016), for (a) patients of all ages, (b) patients aged <65 years, and (c) patients aged ≥65 years. Abbreviations. JPY, Japanese yen; MM, multiple myeloma; PPPM, per patient per month.

Meanwhile, the PPPM costs for other care tended to decrease after 2010 (. For patients aged <65 years, the costs for other care decreased greatly compared with costs for patients aged ≥65 years, from > JPY 200,000 (USD 1,818) to < JPY 150,000 (USD 1,364) (. For those aged ≥65 years, the costs for other care decreased modestly, starting around 2010, from ∼ JPY 150,000 (USD 1,364) to ∼ JPY 120,000 (USD 1,091) (.

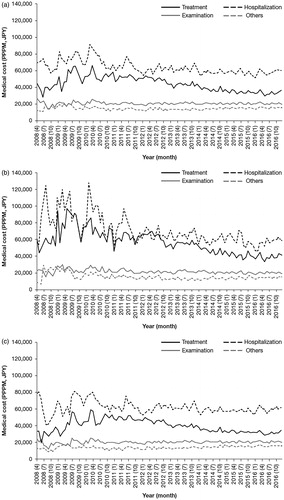

To understand the decreasing trend of other costs shown in , the changes in the four sub-categories of other care costs PPPM were analyzed (). Hospitalization was the most expensive, and costs tended to decrease after 2010 (. Costs for treatment other than MM drugs also showed a decreasing trend after 2010. For patients aged <65 years, both hospitalization costs and treatment costs decreased after 2010 (. For patients aged ≥65 years, the costs for all sub-categories were relatively stable throughout the entire study period, except for a slight decrease in treatment costs after 2010 ().

Figure 4. Medical costs PPPM for medical sub-categories other than MM drugs (treatment other than MM drugs; hospitalization; examination; and other) (April 2008–December 2016), for (a) patients of all ages, (b) patients aged <65 years, and (c) patients aged ≥65 years. Abbreviations. JPY, Japanese yen; MM, multiple myeloma; PPPM, per patient per month.

Discussion

This health insurance claims database study shows the treatment patterns and medical costs for patients with MM in a real-world Japanese setting. The distribution of patients prescribed different MM drugs changed considerably over time, while total medical costs showed a stable trend between 2010 and 2016. The costs for MM drugs increased, while, surprisingly, other care costs showed a decreasing trend from 2010. The change in medical costs differed for the various medical procedure code sub-categories, e.g. hospitalization and non-MM treatment, and between age groups (<65 vs ≥65 years).

This increase in costs for MM drugs is probably due to the launch and implementation of novel drugs: lenalidomide was launched in 2010, pomalidomide and panobinostat in 2015, and carfilzomib in 2016. When considering the reported improvement in the prognosis of patients with MM starting in 2010Citation16,Citation17, the number of patients not responding to standard therapies who received salvage therapy with novel MM drugs may have increased, causing an overall increase in MM drug costs. Changes in prescriptions were observed when each novel drug was launched, suggesting that novel drugs may have been used frequently as salvage therapy immediately after their approval. Prescriptions for combinations that include existing MM drugs changed as well. The distribution of patients prescribed dexamethasone and lenalidomide increased, while the use of melphalan, prednisolone, and thalidomide decreased over time. The decrease in prescriptions for melphalan and prednisolone, which are less expensive drugs for the treatment of MM included in the JSH guidelinesCitation5, suggests a decrease in treatment with a regimen of melphalan/prednisolone (MP) or bortezomib/melphalan/prednisolone (VMP). The increase in prescriptions for dexamethasone may be explained by its use as a concomitant drug for the novel MM drugs.

A notably better prognosis has been reported in patients with MM treated with novel agentsCitation16. The total medical costs PPPM remained almost stable; they did not greatly increase within the 6 years after 2010 included in this study. This is despite the approval and launch of lenalidomide in that year and the launch of other novel drugs in subsequent years. In particular, the use of lenalidomide greatly increased immediately after its approval in 2010, and the treatment of MM in Japan changed substantially from that point. This led to an increase in MM drug costs, but a simultaneous reduction in the costs of other care, particularly hospitalization costs and treatment costs other than for MM drugs.

Overall, changes in MM drug prescription patterns were associated with a trend toward reduced total cost of MM treatment. A European study found that hospitalization costs for patients receiving lenalidomide maintenance therapy were lower than for patients not receiving any maintenance therapyCitation18, which aligns with our exploratory finding of reduced hospitalization costs following the approval of lenalidomide in 2010; however, further investigations are needed to quantify the impact of lenalidomide maintenance therapy on hospitalization costs in Japan. A noteworthy difference was observed in the changes in costs over time for patients above and below the age threshold of 65 years. In particular, costs for hospitalization and treatment tended to decrease from around 2010 for patients aged <65 years. A key difference between patients aged <65 years and ≥65 years is the eligibility for autologous stem cell transplantation in those aged <65 years, although some older patients may also have undergone transplantation, provided they were fit enough. An increase in the use of novel MM drugs may have caused the decrease in hospitalization costs, including treatment costs other than for MM drugs. A more detailed analysis of hospitalization, including frequency and length of stay, is needed to assess whether the recent launch of novel MM drugs caused the reduction in hospitalization costs. The effect of the novel MM drugs on the change in treatment costs other than for MM drugs should also be analyzed in more detail. In addition, treatment patterns for adjuvants such as bisphosphonates, which are frequently used to treat osteoporosis in older patients and are approved for the treatment of bone lesions in MM, may yield insights into how adjuvant therapies can impact hospitalization rates.

In Japan, medical costs for MM are mostly covered by public health insurance. We therefore consider the results of the analysis using data originally intended for public health insurance claims to be reflective of the current status of treatment patterns and medical costs for patients with MM in Japan.

There are also potential limitations to this study. Since the database used in this study only included data from DPC hospitals, which are large hospitals, bias could exist in terms of patients’ clinical history and disease severity. However, we believe that this bias may be limited, because most patients with MM are treated in DPC hospitals. Although the medical costs for patients with MM were analyzed, our data did not allow us to distinguish between costs related to MM and those unrelated to it; consequently, medical costs for diseases other than MM have been included. Results were based on prevalence-based analyses as opposed to an incidence-based analysis. As such, we have not taken treatment phase into consideration. As this study did not distinguish between RRMM and NDMM, it is possible that costs may vary between these patient populations. In our analysis of medical costs, nominal values were used. Nominal values rather than real values are generally used in Japan because of longstanding stable prices. The results may therefore change when taking the biennial revision of the medical payment tariff by the Japanese government into account. However, the annual average rate of change in medical care prices was only –0.14% during our study period. The effects of generic substitutions, such as for lenalidomide and bortezomib, were not considered in this analysis as regulation of generic drugs differ substantially in Japan, where a re-evaluation after 10 years is considered for drugs with an orphan designation, thus generic substitutions were not available in the timeframe studiedCitation19. In addition, as our data source did not include information on clinical or patient-reported outcomes, it was not possible to examine the wider question of value in relation to MM therapies in Japan. Future studies that include such data, either via a prospective study design or use of a database that links costs with outcomes, will provide valuable insight into the value and real-world effectiveness of currently recommended therapies for MM.

Despite these limitations, a change in treatment patterns for MM drugs and medical costs was observed in recent years, a time period in which several novel drugs for MM were launched. The information provided in this study is important when considering treatment strategies and costs for patients with MM.

Conclusions

Changes in treatment patterns for MM drugs and medical costs for patients with MM were analyzed using a claims database. Total medical costs were found to have remained stable since 2010. While costs for MM drugs increased after the launch of lenalidomide in 2010, costs for other care decreased, particularly for hospitalization, including treatment costs other than for MM drugs. The recent launch of novel drugs for the treatment of MM may have caused the change in medical costs. More detailed research is needed to confirm the impact of the launch of these novel drugs on other medical resources used and their associated costs.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Celgene K.K.

Declaration of financial/other interests

SU and TO are employees of Celgene K.K. KI and TT are employees of Milliman, Inc., which has received consultancy fees from Celgene K.K. RG and KS have received advisory/lecture fees from Celgene K.K. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Previous presentation

Parts of this study were presented at the 60th American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting & Exposition, December 1–4, 2018, San Diego, CA, USA.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for initial English language editing. We also wish to thank Saaya Tsutsue for helpful discussions. The authors received editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript from Rosie Morland, PhD, of Excerpta Medica, funded by Celgene Corporation. The authors are fully responsible for all content and editorial decisions for this manuscript.

References

- Cancer Information Service. Cancer registry and statistics. Tokyo: National Cancer Center Japan; 2014.

- Japanese Society of Myeloma. [Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of multiple myeloma]. 4th ed. Bunko-Do: Japanese Society Myeloma; 2016. [Japanese.]

- Hill E, Dew A, Kazandjian D. State of the science in smoldering myeloma: should we be treating in the clinic? Semin Oncol. 2019;46(2):112–120.

- Japanese Society of Hematology. [Multiple myeloma: MM treatment guideline for hematopoietic tumor]. Tokyo: Japanese Society of Hematology; 2018 [cited 2019 June 18]. Available from: http://www.jshem.or.jp/gui-hemali/table.html. Japanese.

- Iida S, Ishida T, Murakami H, et al. JSH practical guidelines for hematological malignancies, 2018: III. Myeloma–1. Multiple myeloma (MM). Int J Hematol. 2019;109(5):509–538.

- Richardson PG, Sonneveld P, Schuster M, et al. Bortezomib or high-dose dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(24):2487–2498.

- Dimopoulos M, Spencer A, Attal M, et al. Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(21):2123–2132.

- Weber DM, Chen C, Niesvizky R, et al. Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma in North America. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(21):2133–2142.

- San Miguel JF, Schlag R, Khuageva NK, et al. Bortezomib plus melphalan and prednisone for initial treatment of multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(9):906–917.

- Benboubker L, Dimopoulos MA, Dispenzieri A, et al. Lenalidomide and dexamethasone in transplant-ineligible patients with myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(10):906–917.

- Fonseca R, Abouzaid S, Bonafede M, et al. Trends in overall survival and costs of multiple myeloma, 2000-2014. Leukemia. 2017;31(9):1915–1921.

- Nakajima R, Aruga A. Analysis of new drug pricing and reimbursement for antibody agents for cancer treatment in Japan. Regul Sci Med Prod. 2017;7(3):173–184.

- Yamabe K, Inoue S, Hiroshima C. Epidemiology and burden of multiple myeloma in Japan: a systematic review. Value Health. 2015;18(7):A449.

- Bolt T, Mahlich J, Nakamura Y, et al. Hematologists’ preferences for first-line therapy characteristics for multiple myeloma in Japan: attribute rating and discrete choice experiment. Clin Ther. 2018;40(2):296–308.e2.

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. [Statistical classification of diseases, injuries and causes of death]. Baltimore: Health Department; 2013 [cited 2019 June 18]. Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/sippei/. [Japanese.]

- Kumar SK, Dispenzieri A, Lacy MQ, et al. Continued improvement in survival in multiple myeloma: changes in early mortality and outcomes in older patients. Leukemia. 2014;28(5):1122–1128.

- Ozaki S, Handa H, Saitoh T, et al. Trends of survival in patients with multiple myeloma in Japan: a multicenter retrospective collaborative study of the Japanese Society of Myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 2015;5(9):e349.

- Ashcroft J, Judge D, Dhanasiri S, et al. Chart review across EU5 in MM post-ASCT patients. Int J Hematol Oncol. 2018;7(1):IJH05.

- Kuribayashi R, Matsuhama M, Mikami K. Regulation of generic drugs in Japan: the current situation and future prospects. AAPS J. 2015;17(5):1312–1316.