Abstract

Aims: The aim of this study was to conduct a cost-effectiveness analysis, as well as a budget impact analysis, on the use of apremilast for the treatment of adult patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis (defined as a psoriasis area severity index [PASI] ≥ 10), who failed to respond to, had a contraindication to, or were intolerant to other systemic therapies, within the Italian National Health Service (NHS).

Materials and methods: A Markov state-transition cohort model adapted to the Italian context was used to compare the costs of the currently available treatments and of the patients’ quality of life with two alternative treatment sequences, with or without apremilast as pre-biologic therapy. Moreover, a budget impact model was developed based on the population of patients treated for psoriasis in Italy, who would be eligible for treatment with apremilast.

Results: Over 5 years, the cost-effectiveness analysis showed that the strategy of using apremilast before biologic therapy was dominant compared with the sequence of biologic treatments without apremilast. In addition, it is important to underline that the use of apremilast slightly increases the quality-adjusted life years gained over 5 years. Furthermore, within the budget impact analysis, the strategy including apremilast would lead to a saving of €16 million within 3 years. Savings would mainly be related to a reduction in pharmaceutical spending, hospital admissions and other drug administration-related costs.

Conclusion: These models proved to be robust to variation in parameters and it suggested that the use of apremilast would lead to savings to the Italian healthcare system with potential benefits in terms of patients’ quality of life.

JEL CLASSIFICATION CODES:

1. Introduction

Psoriasis is a skin disease characterized by variable clinical features, distribution and severity. The most common clinical variant is plaque psoriasis, which accounts for nearly 80–90% of the cases and is characterized by the presence of well-demarcated, erythematous, scaly plaquesCitation1. Psoriatic patients frequently report severe itch and pain, together with various comorbidities that impact their physical, emotional and psycho-social wellbeing, which often lead to an impaired quality of lifeCitation2. The long-term chronic therapies contribute to a major impact in terms of healthcare costsCitation1.

In Italy, the prevalence of psoriasis is estimated at 1.8% of the general population, and up to 4.3% in cases with a family history of the disease; there is a considerable prevalence variability between regionsCitation3.

A list of all drugs currently approved by the European Medical Agency (EMA) for psoriasis and PsA is provided in Supplementary Table S1. Multiple approaches are currently available for the treatment of psoriasis, including topical agents (corticosteroids, vitamin D analogues, dithranol and retinoids), phototherapy (UVB) with or without topical agents, psoralen plus UVA (PUVA), and systemic non-biologic agents (cyclosporine, methotrexate, acitretin, dimethyl fumarate and fumaric acid esters). Other therapeutic options for patients with moderate to severe disease who fail to respond or have a contraindication to systemic non-biologic therapies, are biologic therapiesCitation4. Moreover, in the last few years, new small molecules have been, or are being, developed in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, such as apremilast and tofacitinib. However, at present only apremilast is currently reimbursed in Italy for psoriasis. Apremilast is a selective inhibitor of phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4), which modulates the activity of multiple inflammatory mediators involved in psoriasis, such as TNF-α, IL-23, IL-17 and other inflammatory cytokinesCitation5. Apremilast is well tolerated and effective in improving moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis; it reduces the Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI)-75 response and an improvement in pruritus, nail disease, scalp involvement and patient’s quality of life, measured by the Dermatology Quality of Life Index (DQLI), is also observedCitation6. In Europe, apremilast is currently indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis in adult patients who failed to respond to, have a contraindication to, or are intolerant to other systemic therapies, including cyclosporine, methotrexate or psoralen and ultraviolet-A light (PUVA)Citation6.

Therefore, the aim of this study is to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of apremilast administered before biological therapies within the Italian National Health Service (NHS), and the budget impact of apremilast in terms of expenditures associated with the treatment. In this way, we aimed to obtain information regarding the likelihood of apremilast given its benefits in terms of patients’ quality of life and its potential savings on the payers’ budget.

2. Cost-effectiveness analysis

A cost-effectiveness analysis has been performed on the use of apremilast (Otezla) in the Italian healthcare system, which aims to assess the cost-effectiveness of placing oral apremilast within the current context of the Italian NHS and to provide guidance for efficient resource allocation for patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Based on the available literature, we developed a model simulating the costs associated with resource utilization and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) gained of a cohort of patients following two alternative treatment sequences.

2.1. Methods

A Markov state-transition cohort model was developed in Excel 2013 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA), and adapted to the Italian National Health Service (NHS) to compare costs and QALYs gained, in a cohort of patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis based on two alternative treatment sequences with or without apremilast. This statistical model allows comparison between treatment sequences, and it is useful in the setting of psoriasis as these patients are more likely to receive multiple lines of therapy over the years, due to adverse effects or waning efficacyCitation7. The model framework was adapted from the University of York Assessment Group model for psoriasis, already validated in literatureCitation7,Citation8.

In this sequential-treatment model, each treatment line is considered to be a mutually exclusive health state. In this adaptation of the sequential-treatment model of the Italian system, the timeframe of the analysis was limited to 5 years, given the particularly high rate of switching among therapies, which makes it very difficult to have reliable long-term analysis.

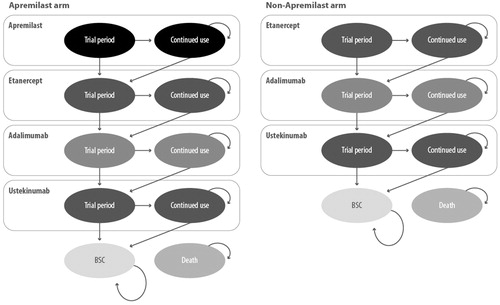

In the base case, the following two treatment sequences were compared ():

Apremilast → Etanercept (Enbrel) → Adalimumab (Humira) → Ustekinumab (Stelara) → Best supportive care

Etanercept (Enbrel) → Adalimumab (Humira) → Ustekinumab (Stelara) → Best supportive care

For best supportive care (BSC), the UK guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) on resource utilization for palliative care were used for therapy prescription in the event of discontinuation of all previous treatmentsCitation9, given the lack of similar guidelines in the Italian context.

Patients entered the model in a health state dictated by the treatment pathway under investigation, either apremilast (in the apremilast cohort) or the selected biologic therapy in the comparator cohort. The biologic treatment sequence used in the base case was determined by expert opinions, considering the most frequently used biologic drugs at the time of the analysis. For patients not responding to, or discontinuing other treatment options, the sequence consisted of etanercept, followed by adalimumab, ustekinumab and, finally, BSC according to the NICE guidelinesCitation9. Patients receiving apremilast as first-line therapy were transitioned to the biologic therapy sequenceCitation10.

The duration of the trial period ranged between 12 and 16 weeks, depending on the treatment received, as detailed later. Adverse events were not included in the model. This choice is likely to be conservative, as apremilast has a strong safety and tolerability profile associated with minor adverse events.

In the model, the following assumptions were made: (a) patients who were entered in the model followed two phases: a “trial period”, in which the response to treatment was evaluated, and a “continued use” phase of therapy, in case of positive response in the trial period; (b) treatment interruption and transition to the subsequent line; (c) non-responders to any therapy (during both the trial period and the continued use phase), switched directly to the subsequent line, without any temporal interruptions.

Response to active therapy was assessed at the end of the trial period using the PASI-75 response criteria: patients achieving this outcome were assumed to remain on the treatment until withdrawal due to either loss of efficacy or another cause according to a comprehensive, long-term withdrawal probability. Non-responders and patients who discontinued during the continued-use phase were assumed to progress to subsequent lines of therapy.

The model was based on a cycle length of 28 days for each Markov cycle, with 1 year corresponding to 13 cycles, because this offered the best compromise for the different durations of the apremilast and biologic trial periods.

This model used the efficacy data of a network meta-analysis already applied by Bewley et al., with the aim of retrieving similar cost-effectiveness data of apremilast for NHS EnglandCitation7.

2.2. Input data

2.2.1. Efficacy data and utility weights

Patients entering the model were adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis (≥PASI-10), with contraindications to, intolerance to or discontinuation of, other systemic therapies. In the absence of direct comparison between the various treatment lines, the PASI-50/75/90 response rates were used to feed the model ()Citation11. Duration of the trial period for the individual treatments was 16 weeks for apremilastCitation12, adalimumab (Humira)Citation13 and ustekinumabCitation14 and 12 weeks for etanercept (Enbrel)Citation15. The dropout rate was 20% for biologic treatmentsCitation16, and it was assumed to be equal for apremilast. This assumption was made in other recently published similar cost-effectiveness analysesCitation7. PASI-50/75/90 data were used to calculate EQ-5D utilities, both for baseline utility and for changes in utility obtained from pooled estimates of the apremilast trial data. To estimate utlity weights associated with PASI scores, a published linear regression of the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) relative to PASI was used. The utility score for patients in BSC was set at 0.70Citation17, and utility gains from treatment were estimated using the mean difference in EQ-5D scores from baseline for each PASI category (i.e. <PASI-50, ≥PASI-50 to < PASI-75, ≥PASI-75 to < PASI-90 and ≥ PASI-90).

Table 1. Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI)-50/75/90 response rate reported by Mughal et al. ISPOR 18th Annual European Congress; 2015.

2.3. Cost data

All economic values are expressed in euros (€), at the rates available for the year 2019. No changes in the tariffs of healthcare procedures took place in the last few years. Treatment frequency, dosage and mode of administration were based on SmPCs and clinical input. As it regards drug costs, the first three cycles of therapy also included the costs of induction, if present. The annual costs of treatment were calculated using the prices extrapolated from the list prices and the doses indicated in the SMPCs of the drugs. The list prices in do not include the mandatory discounts to be applied to these products according to the Italian legislationCitation18,Citation19, nor any confidential discount.

Table 2. Comparison of the acquisition costs among different treatments.

The model also incorporates the costs associated with physicians’ visits, screening and monitoring tests (e.g. lipid panel, hepatic function panel, renal panel, complete blood count, PCR, electrocardiography, chest X-ray, etc). Resource use associated with these events (physicians’ visits, screening and monitoring tests) was obtained from official tariffs for outpatient servicesCitation20, and the costs of the most frequent laboratory tests are reported in . The frequency of tests was hypothesized to be every 4 months for adalimumab and etanercept, and once every three months for ustekinumab. Biologic drugs alone were considered for the model, as apremilast does not require screening and monitoring testsCitation21. The frequency of physicians’ visits was assumed to be every 6 months for apremilast given the safety profile of the drug, every 4 months for adalimumab and etanercept, and every three months for ustekinumab.

Table 3. Laboratory tests suggested for each treatment.

It was assumed that patients who dropped out of all previous lines of therapy were treated with conventional systemic medicinal products, such as cyclosporine or methotrexate. The annual costs of treatment were calculated using the prices extrapolated from the list prices and the doses indicated in the drugs’ SMPCs. Monthly costs resulted equal to €187.87 for cyclosporine and €20.56 for methotrexate. It was also assumed that half of the patients received cyclosporine and half of the patients received methotrexate. A 3% discount rate was applied to costs and QALYs according to Italian guidelinesCitation22.

2.4. Results

2.4.1. Base case results

Over the 5-year period of the analysis, the total costs of the strategy including apremilast was €57,965 versus €59,134 for the strategy with biologic molecules alone, with a saving of €1,169.00. In addition, the use of apremilast slightly increased QALYs gained over 5 years (3.96 vs 3.95). Overall, of the €1,169 saved over 5 years, €657 were associated with the reduced treatment costs, €252 were associated with reduced monitoring costs, and €259 were associated with base case costs. The total costs and QALY per patient are provided in .

Table 4. Base case cost-effectiveness results.

2.4.2. Sensitivity analysis

To address the issue of uncertainty around model parameters, both deterministic sensitivity analysis (DSA) and probabilistic sensitivity analyses (PSA) were conducted.

In the univariate DSA, treatment efficacy was varied according to the 95% CIs reported in the literatureCitation11, and the utility weights according to the 95% CIs in the Woolacott studyCitation8. it was also assumed that apremilast cost varied by 10% and base case costs by 25%. In addition, a variable discount rate from 0% to 6% was applied to both costs and benefits. The model showed that the sequence including apremilast was economically more convenient in all cases, except for the case of reducing the utility of the achievement of PASI-90 (in which case apremilast resulted less costly but also slightly less effective). Results were therefore robust to changes in model parameters.

Model results were very sensitive to changes in the timeframe of the analysis. For example, over a period of 40 years, the use of apremilast resulted as more effective, but also more costly, with an incremental cost per QALY gained of €35,329.

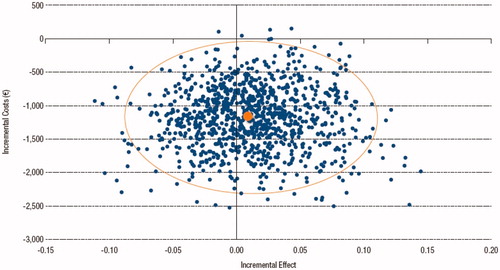

In the PSA, Dirichlet distributions were associated with treatment efficacy, beta distributions to drop-out rates, normal distributions to utility weights and uniform or gamma distributions to cost parameters. The Monte Carlo simulation showed that apremilast remained to be cost saving in 99.5% of cases, while there was more uncertainty around efficacy results, although the sequence including apremilast remained dominant in more than 60% of simulations ().

3. Budget impact analysis

In order to estimate the impact on NHS spending derived from the introduction of apremilast for the treatment of psoriasis in Italy, a budget impact model (BIM) was developed. The model is based on the population of patients treated for psoriasis in Italy who are eligible for treatment with apremilast according to the indication approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA), i.e. adult patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis (defined by a PASI score ≥10) who failed to respond to or who have a contraindication to, or are intolerant to other systemic therapies, including cyclosporine, methotrexate or PUVA. The model therefore calculates the annual costs for patients for each treatment available on the market and the costs associated with the introduction of apremilast. Based on current treatments, total annual costs were calculated, including the cost of the drugs, administration, monitoring and any hospital admissions required to prepare the patient for treatment with the available biologic therapies. In a similar way, the total annual costs for apremilast were calculated.

Two scenarios may occur: the present scenario should be balanced with the alternative scenario in which apremilast gains market shares and thus the number of patients treated with apremilast increases, with a proportionate reduction in the number of patients treated with other biologic agents. The cost differences between the two scenarios represent the potential budget impact of apremilast. The simulation is calculated for the first 3 years of use of apremilast from the perspective of the Italian NHS.

3.1. Results

Mean age of the patients in the model was 45 years, with a mean body weight of 91 kg. The calculation of the number of patients eligible to apremilast was based on the prevalence of patients with psoriasis in Italy, which is 2.90%Citation23. With the general population of 60,665,551 inhabitants in Italy (in 2017)Citation24. Considering that the proportion of people suffering from moderate to severe plaque psoriasis is 2.64% (IQVIA, data on file), and considering the number of subjects with moderate to severe psoriasis who failed to respond to, or who have a contraindication to, or are intolerant to, other systemic therapies, 34.4% (IQVIA, data on file), the estimated number of patients eligible for apremilast being 15,950 for the first year of the model. Assuming an annual growth rate in the number of patients of 9.50% (IQVIA, data on file), the number of patients potentially eligible for apremilast becomes 17,465 and 19,124, for the second and third year, respectively.

Two scenarios were compared: a first scenario (current scenario), which is based on current market shares of biologic agents, excluding apremilast, and an alternative scenario, which assumes a gradual increase in the use of apremilast for patients with psoriasis at the rate of 5%, 12% and 15% in the first, second and third years, respectively. The introduction of apremilast would proportionally reduce the use of other biologic agents, with respect to the current scenario, except for the biosimilar infliximab and etanercept, for which the number of patients treated was expected to grow.

For biologic agents, the costs of drug infusion were assumed considering that the first administration occurs in a hospital setting. Hospital-only administration was assumed for infliximab and ustekinumab. No administration costs were attributed to apremilast, which as an oral formulation and thus it does not require in-hospital admission for administration. For each treatment, an average number of visits to the physician was assumed. The unit cost of a physician visit was obtained from official tariffsCitation20. As apremilast does not require screening and monitoring testsCitation21, fewer visits were assumed than for biologic therapies.

For biologic therapies, the number of hospital admissions needed on average before the patient starts treatment was considered, as indicated in a Health Technology Assessment (HTA) report of apremilast in the Italian settingCitation25. For each biological, a cost for the first year of €217 was calculated, i.e. the average cost for hospital admission in preparation for treatmentCitation26. Importantly, the reported costs are an average, as not all patients need to be admitted to the hospital. The average cost was calculated using the relevant diagnosis-related group (DRG) (696 – psoriasis and similar conditions), supplemented as necessary when hospitalization required days in hospital exceeding the threshold value for the individual DRG. Furthermore, the treatment with biologic therapies involved an increase in the use of concomitant medicinal products equal to an average annual cost of €20.00 per patientCitation26.

The prices of the drugs are calculated both for induction and for a year of maintenance. The annual cost was calculated using the list price published in the individual Official Gazettes, and therefore does not include the mandatory discounts and confidential discounts. shows the total annual expenditure for each medicinal product in the scenario without apremilast, while the annual expenditure with apremilast is presented in .

Table 5. Total spending without apremilast.

Table 6. Total spending with apremilast.

The impact of apremilast on the Italian NHS budget obtained from the difference between the scenarios with and without apremilast, is shown in . It was estimated that the use of apremilast would lead to an annual saving of €2.5 million, €6.2 million and €15.9 million in the first, second and third year of marketing, respectively. Over the 3-year period, this would bring a total saving of €16.8 million.

Table 7. Budget impact per item of spending.

The most significant spending item in the 3-year period is the reduction in pharmaceutical spending of €16,884,498 followed by the spending for hospital admissions of €1,250,353 and the costs of drug administration of €401,954 ().

4. Discussion

Apremilast is an orally administered treatment option for psoriasis. It is a PDE4 inhibitor with proven efficacy and a favorable safety profile, not requiring any type of screening or routine laboratory monitoring. The efficacy and safety of apremilast have been shown in two large phase III randomized controlled trials and post-marketing studiesCitation27–29. However, no data regarding the cost-effectiveness or economic impact of introducing apremilast in clinical practice in Italy have been published on peer-reviewed journals.

The aims of this research were to assess the cost-effectiveness of such option in the setting of the Italian NHS, and to perform a budget impact analysis with two alternative scenarios related to the introduction of apremilast.t

4.1. Cost-effectiveness analysis

Although the Italian Drug Agency (Agenzia Italiana del FArmaco, AIFA) does not strictly require any mandatory cost-effectiveness analysis for new drugs entering the market, and it does not apply any official threshold of cost/QALY, the findings of this analysis can be helpful, to assess the ideal therapeutic sequence for psoriasis patients, both from the clinical and the economic perspective. In fact, the introduction of apremilast as an alternative to biologic therapies could represent an effective treatment option in both economic and quality of life perspective for patients with plaque psoriasis with PASI ≥10, who cannot undergo the currently existing systemic therapies.

From a cost-effectiveness perspective, the most important results derive from the in the base case scenario, in which apremilast was given before adalimumab, etanercept and ustekinumab in the treatment sequence. Importantly, Bewley et al. already showed that the presence or absence of ustekinumab within the treatment sequence did not change the conclusion of the cost-effectiveness result, and that cost-effectiveness was also not affected by neither secukinumab nor infliximabCitation7. These drugs are the currently available treatment options for psoriasis in Italy. On the other hand, there are several new therapies (i.e. secukinumab, ixekizumab, brodalumab and guselkumab) that were not included in the analysis, since they were available yet in Italy at the time of the analysis.

In their cost-effectiveness network meta-analysis, Bewley et al. obtained similar economic results in the context of the English NHS as we obtained with our research. In fact, their base case indicated a QALY gain of 0.09 of placing apremilast before TNF-α inhibitors, compared with TNF-α inhibitors alone, although this strategy carries a cost increase in UK of £1,882 during a 10-year period. They also conclude that the introduction of apremilast shortened the average time spent on biologics by 0.44 years (3.92 vs 4.36 years), and decreased the time spent in BSC by more than 1 year in the apremilast sequence (4.50 vs 5.52 years), with concomitant increase in the average time spent at PASI-75 by 0.73 (4.58 vs 3.84 years). The work by Bewley et al. also underlines that data regarding the comparison of apremilast with biologic treatments can be obtained only by network meta-analysis, due to the lack of head-to-head comparison studies. Notably, direct comparison of two interventions (i.e. apremilast vs etanercept, apremilast vs adalimumab, etc.) may not be necessary, considering that patients with psoriasis frequently undergo various biologic therapies during the course of their diseaseCitation30.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to deal with the uncertainty of many of the model parameters. Consistent with the base case, the apremilast sequence dominated the comparator sequence in almost all the univariate sensitivity analyses considered, being dominant or cost-effective in almost 100% of the 1,000 simulations performed. These analyses highlighted that the benefits of including apremilast at the beginning of therapy are due to a medium-term reduction and delay in progression to the more expensive and potentially less well-tolerated treatments, such as the biologic treatments. This effect is reflected in a reduction and delay in the access to the base case. Therefore, the model is highly dependent on long-term outcomes, in particular, regarding the cost and health-related quality of life-related measures associated with the base case. This also explains the lower efficacy of the apremilast-including strategy when the time horizon of the model was set at 40 years, because the benefits of the delay in access to the base case were mitigated (although apremilast remained slightly more cost-effective).

Overall, it can be stated that the model was robust to variation in parameters and it suggested that the use of apremilast would lead to savings to the Italian healthcare system with potential benefits in terms of patients’ quality of life.

4.2. Budget impact analysis

From a financial sustainability perspective, the budget impact analysis showed that the increased use of apremilast in the Italian NHS (up to 15%) displacing branded biologic therapies might lead to €16 million savings in 3 years. In detail, the base case assumption considering the administration of apremilast before the standard sequence of branded biologic therapies, leads to an annual saving of €2.5 million, €6.2 million and €15.9 million in the first, second and third year of apremilast, respectively.

4.3. Limitations of the studies

Some limitations of the studies should be acknowledged.

First, data on treatment efficacy were based on a network meta-analysis and lacked comparative long-term data on treatment efficacy. Although various publications have attempted to synthesize long-term outcomes across trials, there are no valid ways to make comparisons due to differences in study design and choice of statistical analysis. Moreover, the studies do not include all available therapies for psoriasis and, the economic models might not necessarily reflect the current pricing and reimbursement conditions of the therapies that have been included (only publicly available list prices could be incorporated within the analysis).

The cost-effectiveness analysis showed that the strategy of using apremilast as first option in the sequence of treatment before biologic therapy was dominant over the sequence of biological treatments without apremilast during a 5-year period, and it represents a potential cost-saving option for the Italian NHS. However, the choice of treatment sequence in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis is frequently dependent on both patients and physicians experience and preferences.

Within the cost-effectiveness analysis, the sequence of three biological therapies was based on market leaders shares at the time of the analysis and experts’ opinion, excluding other available treatments such as new originators or biosimilars. This sequence may therefore not reflect each individual patient’s treatment. Patients can also follow several different treatment pathways, as guidelines do not specify any sequence of treatment for biologic therapies. Moreover, at the time of the study, market shares of recently launched therapies (including biosimilars) were not fully available.

Furthermore, to obtain a real estimate of apremilast cost-effectiveness in real practice, it is important to account for the cost of base case, which cannot be completely estimated in this type of model analysis.

In addition, the benefits of each treatment in terms of response rate were assumed to be independent of its place in therapy: namely, the response rate for a therapy was considered to be the same whether it was received before or after other treatments. This assumption is uncertain; however, the two treatment sequences compared in our research consist of the same sequence of biologic agents, and thus there should be no impact on the final incremental cost-effectiveness ratio. Furthermore, no similar cost-effectiveness analysis or budget impact analysis of apremilast in the context of the Italian NHS have been published to date, and thus full comparisons of our results cannot be made. Three abstracts assessing the cost-effectiveness of apremilast administered before biologic therapies were retrieved in Europe, one in UKCitation31, one in SpainCitation32 and one in ScotlandCitation33, in addition to the already mentioned network meta-analysis by Bewey et al. in the English NHSCitation7. In all cases, treatment with apremilast resulted either dominant or cost-effective. Finally, the QALY outcome measure might not fully capture the innovation represented by the oral route of administration of apremilast versus current injectable therapies, therefore benefits with apremilast might have been underestimated.

5. Conclusion

The results of this study suggest that resource optimization can be achieved with the use of apremilast, which is an orally administered drug with proven efficacy and favorable safety profile. In fact, the use of apremilast would lead to potential savings to the Italian health care system with potential benefits in terms of patients’ quality of life, according to the simulations performed with two different models of cost-effectiveness and budget impact analysis.

Transparency statement

Declaration of funding

Celgene Italy funded the adaptation of the economic models presented in this research, as well as the editorial assistance for the preparation of the manuscript.

Declaration of financial/other interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest. A peer reviewer on this manuscript has disclosed that one of their employers has previously received funding from Celgene, however, this was not for apremilast, psoriasis, and/or PsA. By company policy, employees cannot hold equity in sponsor organizations except through independently managed investments, cannot provide services directly to sponsor organizations, and cannot receive compensation directly from sponsor organizations. The peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Author contributions

All authors directed the research project, conducted the analysis, and retrieved the results, and are fully responsible for all content and editorial decisions for this manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (27.6 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge financial support for this study from Celgene Italy for adapting the economic models, critical review and to support the writing of the manuscript. Editorial assistance for the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Luca Giacomelli, PhD, Ambra Corti, and Aashni Shah (Polistudium) on behalf of Content Ed Net.

References

- Nestle FO, Kaplan DH, Barker J. Psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(5):496–509.

- Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, et al. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133(2):377–385.

- Lebwohl MG, Bachelez H, Barker J, et al. Patient perspectives in the management of psoriasis: results from the population-based multinational assessment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(5):871–881.

- National Clinical Guideline Centre (UK). Psoriasis: assessment and management of psoriasis. NICE Clinical Guidelines. No. 153. London: Royal College of Physicians (UK); 2012.

- Abdulrahim H, Thistleton S, Adebajo AO, et al. Apremilast: a PDE4 inhibitor for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2015;16(7):1099–1108.

- Otezla. Summary of Product Characteristics [Internet]. [cited 2019 May 8]. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/health/documents/community-register/2015/20150115130395/anx_130395_en.pdf.

- Bewley A, Barker J, Mughal F, et al. Cost-effectiveness of apremilast in moderate to severe psoriasis in the United Kingdom. Cogent Med. 2018;5(1):1495593..

- Woolacott N, Hawkins N, Mason A, et al. Etanercept and efalizumab for the treatment of psoriasis: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess. 2006;10(46):1–233.

- National Clinical Guidelines Centre. Appendix P – Review of resource use and cost data to use in defining ‘best supportive care’ for NCGC economic model [Internet]. [cited 2019 May 8]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg153/evidence/appendices-ju-pdf-188351538.

- Iskandar IY, Ashcroft DM, Warren RB, et al. Patterns of biologic therapy use in the management of psoriasis: Cohort study from the British Association of Dermatologists Biologic Interventions Register (BADBIR). Br J Dermatol. 2017;176(5):1297–1307.

- Mughal F, Cawston H, Kinah D, et al. Cost effectiveness of Apremilast in moderate to severe psoriasis in Scotland. ISPOR 18th Annual European Congress. 2015. Nov 7–11; MiCo - Milano Congressi, Milan, Italy.

- Papp K, Reich K, Leonardi CL, et al. Apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor, in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: results of a phase III, randomized, controlled trial (Efficacy and Safety Trial Evaluating the Effects of Apremilast in Psoriasis [ESTEEM] 1). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(1):37–49.

- Saurat JH, Stingl G, Dubertret L, et al. Efficacy and safety result from the randomised controlled comparative study of adalimumab vs. metotrexate vs. placebo in patients with psoriasis (CHAMPION). Br J Dermatol. 2007;158(3):558–566.

- Leonardi CL, Kimball AB, Papp KA, et al. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab, a human interleukin-12/23 monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriasis: 76-week results from a randomised, double blind, placebo-controlled trial (PHOENIX 1). Lancet. 2008;371(9625):1665–1674.

- Leonardi CL, Powers JL, Matheson RT, et al. Etanercept as monotherapy in patients with psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(21):2014–2022.

- Turner D, Picot J, Cooper K, et al. Adalimumab for the treatment of psoriasis. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13 (Suppl 2):49–54.

- Revicki DA, Willian MK, Menter A, et al. Relationship between clinical response to therapy and health-related quality of life outcomes in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Dermatology. 2008;216(3):260–270.

- DETERMINAZIONE AIFA 3 luglio 2006. Elenco dei medicinali di classe a) rimborsabili dal Servizio sanitario nazionale (SSN) ai sensi dell’articolo 48, comma 5, lettera c), del decreto-legge 30 settembre 2003, n. 269, convertito, con modificazioni, nella legge 24 novembre 2006, n. 326. (Prontuario farmaceutico nazionale 2006). (Gazzetta Ufficiale Serie Generale n.156 del 07-07-2006 - Suppl. Ordinario n. 161)

- DETERMINAZIONE AIFA 27 settembre 2006. Manovra per il governo della spesa farmaceutica convenzionata e non convenzionata. (Gazzetta Ufficiale Serie Generale n.227 del 29-09-2006)

- Ministero della Salute. Remunerazione delle prestazioni di assistenza ospedaliera per acuti, assistenza ospedaliera di riabilitazione e di lungodegenza post acuzie e di assistenza specialistica ambulatoriale. Gazzetta Ufficiale – Serie Generale n. 23 del 28-01-2013. Suppl. Ordinario n. 8.

- Mease PJ. Apremilast: A phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis. Rheumatol Ther. 2014;1(1):1–20.

- Associazione Italiana di Economia Sanitaria. Proposta di linee guida per la valutazione economica degli interventi sanitari. Politiche Sanitarie. 2009;10(2):91–99.

- Saraceno R, Mannheimer R, Chimenti S. Regional distribution of psoriasis in Italy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol. 2008;22(3):324–329.

- Istituto Nazionale di Statistica [Internet]. Available from: www.istat.it.

- Kheraoui F, Favaretti C, Ferriero AM, et al. Apremilast nel trattamento della psoriasi e dell’artrite psoriasica: risultati di una valutazione di Health Technology Assessment. QIJPH. 2017;6(2):1–116.

- Degli Esposti L, Perrone V, Sangiorgi D, et al. Analysis of drug utilization and health care resource consumption in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis before and after treatment with biological therapies. BTT. 2018;12:151–158.

- Nash P, Ohson K, Walsh J, et al. Early and sustained efficacy with apremilast monotherapy in biological-naïve patients with psoriatic arthritis: a phase IIIB, randomised controlled trial (ACTIVE). Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(5):690–698.

- Reich K, Gooderham M, Green L, et al. The efficacy and safety of apremilast, etanercept and placebo in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: 52-week results from a phase IIIb, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (LIBERATE). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(3):507–517.

- Papadavid E, Rompoti N, Theodoropoulos K, et al. Real-world data on the efficacy and safety of apremilast in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(7):1173–1179.

- Mughal F, Barker J, Cawston H, et al. Cost-effectiveness of apremilast in moderate to severe psoriasis in the UK. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5):AB243.

- Carrascosa JM, Vanaclocha F, Caloto T, et al. Cost-utility analysis of apremilast for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis. Value Health. 2015;18(7):A420.

- Mughal F, Cawston H, Kinahan D, et al. Cost-effectiveness of apremilast in moderate to severe psoriasis in the Scotland. Value Health. 2015;18(7):A420.

- Levin AA, Gottlieb AB, Au SC. A comparison of psoriasis drug failure rates and reasons for discontinuation in biologics vs conventional systemic therapies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13(7):848–853.