Abstract

Objective: To assess the cost-effectiveness of clopidogrel versus aspirin for high risk patients (pre-existing symptomatic atherosclerosis or multi-vascular territory involvement) with established peripheral arterial disease (PAD) for secondary prevention of atherothrombotic events in a Chinese setting.

Methods: A Markov model with a lifetime horizon was developed from the perspective of the national healthcare system in China. The primary outputs are quality adjusted life years (QALYs), direct medical costs, and the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs). Clinical efficacy data were obtained from the CAPRIE trial. Drug acquisition cost, other direct medical costs, and utilities were from pricing records and the literature. One-way sensitivity analysis and probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) were conducted to test the robustness of the model on all parameters.

Results: In patients with pre-existing atherosclerosis, 2 years of treatment with clopidogrel and aspirin would yield total QALYs of 8.776 and 8.576 at associated costs of ¥18,777 ($2,838) and ¥12,302 ($1,859), respectively, resulting in an ICER of ¥32,382 ($4,893) per QALY gained. In patients with PVD, secondary prevention with the same drugs would expect to lead to total QALYs of 8.836 and 8.632 at associated costs of ¥18,518 ($2,798) and ¥12,041 ($1,820), respectively, resulting in a corresponding ICER of ¥31,743 ($4,797) per QALY gained. The results were most sensitive to the discount rate for future outcomes and costs. The PSA indicated that the probability of clopidogrel being cost-effective was 100% at the willingness-to-pay threshold of 3-times GDP.

Conclusions: Secondary prevention with clopidogrel is an attractive cost-effective option compared with aspirin for high risk patients with established PAD from the perspective of the national healthcare system in Chinese settings.

Introduction

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) can have a wide spectrum of clinical presentations, ranging from individuals who are asymptomatic to those with critical limb ischemia, in which the blood in the lower extremities is severely reduced due to the arterial blockage. Largely owing to its insidiousness presentation, PAD often remains undiagnosed, even in western countries with an advanced healthcare system, such as in the USACitation1. However, atherosclerosis risk factors are highly prevalent in PAD patients and there is a rich body of literature indicating PAD with a greatly increased risk of major cardiovascular events and death. In fact, data generated through the REACH registry showed that patients with PAD had about one-third higher risk of major cardiovascular events over 1-year follow-up than in with coronary or cerebral artery disease, and the greater the number of vascular sites affected by disease, the higher the mortalityCitation2. While it is expected that mortality risk was higher in symptomatic PAD patients compared with asymptomatic patientsCitation3, the latter group is also at a significantly high risk of cardiovascular death. Evidence from a meta-analysis indicated that the 10-year cardiovascular mortality risk among asymptomatic PAD patients was 4.2-times higher in men and 3.5-times higher in women compared with non-PAD individualsCitation4.

The prevalence of PAD appears to vary considerably with ethnicity origin. In a pooling study of seven US populations, PAD in individuals aged >40 years was found to be highest in African-American (8.8%), followed by Native American (6.1%), non-Hispanic white (5.5%), Hispanic (2.8%), and Asian individuals (2.6%)Citation5. Another systematic review of studies also found a lower prevalence of PAD among south Asian individuals in the general populationCitation6. A large population-based investigation of PAD conducted in China by measuring ankle brachial index in six regions with 21,152 adult participants showed that the prevalence of PAD was ∼3.08% in the general population. As expected, the risk of PAD had a highly positive correlation with age, body weight, smoking, diabetes, high blood pressure, dyslipidemia, coronary heart disease, and ischemic strokeCitation7. In a separate study conducted in China, among patients with diabetes or metabolic syndrome, the prevalence of PAD was as high as 38.7% and 45.1%, respectivelyCitation8. Largely owing to the aging population and increased diabetes in China, the PAD prevalence is expected to rise and remains a significant threat to public health.

Antiplatelet therapy is a cornerstone in the prevention of atherothrombotic events by inhibiting thrombus formation. Both acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) and clopidogrel are such therapies of standard of care but with different mechanisms of action. The relative clinical efficacy of clopidogrel vs aspirin for secondary prevention of vascular events was demonstrated in the Clopidogrel vs Aspirin in Patients at Risk of Ischemic Events (CAPRIE) trial with a comparable safety profile in patients with atherothrombotic diseases. The CAPRIE trial enrolled patients with atherosclerotic vascular disease manifested as either recent myocardial infarction (MI), recent ischemic stroke (IS), or symptomatic PAD, and showed an overall 8.7% relative risk reduction (p = .043) in the primary composite endpoint of MI, IS, or vascular death over an average of 1.91 years of follow-upCitation9. However, the clinical benefits did not appear to be uniform across the three clinical sub-groups; patients with PAD experienced a much larger relative-risk reduction (23.8%), and the test of heterogeneity of treatment effects was also statistically significant. Additionally, further analyses of the CAPRIE trial data revealed that patients with pre-existing symptomatic atherosclerotic disease or those with multi-vascular territory involvement, aka polyvascular disease (PVD) with PAD were at a much higher risk of ischemic events, and the efficacy of clopidogrel was more pronounced in treating these two sub-populationsCitation10,Citation11. Consistent with the clinical evidence, the current Chinese treatment guidelines for PAD recommend long-term use of either clopidogrel or aspirin for secondary prevention of vascular events in individuals with established PADCitation12. The greater clinical benefits associated with clopidogrel, however, should be balanced against its higher cost, more so in resource-limited countries. In light of the paucity of health economic data on choices of long-term use of antiplatelets and the potential public health impact with optimum clinical management of PAD in China, we conducted this cost-effectiveness analysis comparing clopidogrel with aspirin for secondary prevention of vascular events in high risk patients with established PAD from the perspective of the national healthcare system in China.

Methods

Model structure

We built a Markov model, which shared the same structure as models previously developed for similar objectives based on the CAPRIE trial and/or at different settingsCitation11,Citation13,Citation14. The model compared the lifetime health outcomes and costs associated with clopidogrel vs aspirin for secondary prevention of vascular events in high risk patients with established PAD in the Chinese setting. High risk was defined as patients with either pre-existing symptomatic atherosclerotic disease or those with PVD. The primary outputs of the model were quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) gained and associated direct medical costs. Cost-effectiveness was evaluated using the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), which is calculated as the ratio of the mean incremental cost over the mean number of incremental QALYs for clopidogrel compared with aspirin. The simulation for each cycle is a 6-month duration with half-cycle correction, and patients can remain in their current health state, have a new event, or die at each cycle, as determined by the transitional probabilities. The time horizon was lifetime and a 3.5% discounting rate per annum was applied to both future health outcomes and costs, which were calculated from the perspective of the national healthcare system in China.

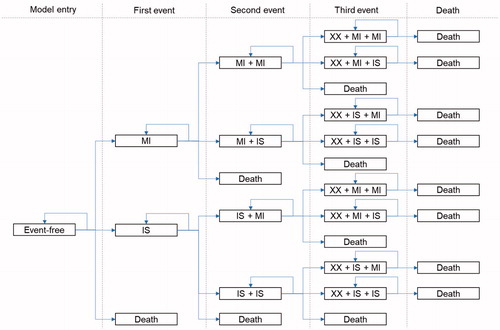

The Markov model consisted of three mutual exclusive health states, MI, IS, and death (due to fatal cardiovascular events or other causes). Simulated patients enter the model in a state of “event-free” and pass through a sequence of health states according to transition probabilities. As patients may experience multiple subsequent ischemic events, which would have implications on both health outcomes and costs, the model distinguished between three sub-states within each health state, i.e. patients could experience a second MI, a second stroke, a stroke after an MI, an MI after a stroke, or death. Finally, patients can experience a third event or die ().

Model inputs

Effectiveness estimates

A post-hoc analysis of the PAD sub-group of the CAPRIE trial was conducted to generate the transition probabilities of ischemic events or death. The transition probabilities were differentiated depending on the elapsed time since the previous event (0–6 months, 7–12 months, or later months), and the previous event itself (MI or IS). A separate set of transition probabilities was generated for each high risk sub-group (pre-existing symptomatic atherosclerotic disease or PVD) and the risk ratios of ischemic events due to the high risk factors were applied as investigated from the Sweden study on the high risk groupsCitation11 and the post-hoc analysis. The risk of death of MI or IS consisted of two time periods: the acute fatality rates of MI or IS were from the post-hoc analysis of the CAPRIE trialCitation9 and the longer-term mortality after MI or IS was estimated based on the survival function for patients with atherosclerotic vascular diseaseCitation15. The transition probabilities by treatment arm for the PAD sub-group and the relative risks of the events during the first cycle for the two high-risk sub-populations are shown in and .

Table 1. The transition probabilities sourced from the post-hoc analysis of the peripheral arterial disease sub-group of the CAPRIE trial.

Table 2. Relative risks of ischemic events for the PAD sub-group with high-risk factors vs the general PAD sub-group.

Health utilities

In the cost-utility analysis, the life-year spent at each health state was adjusted by its utility value reflecting the quality-of-life at such state. Utility values associated with various health states were directly extracted from published literatureCitation11, as displayed in . In the published literature, health utilities associated with initial MI or IS events were based on earlier studies. In the case of subsequent events, utility values were assumed to be equal to the product of the individual utilities. The utility for three sequential events was similarly derived.

Table 3. Utility values of health states in the model.

Cost estimates

All cost inputs used in the model were China-based, and only direct medical costs were considered, using 2018 Chinese RMB (¥) (the average conversion rate in 2018: $1 USD = ¥6.6174 RMB) and estimated from the perspective of the national healthcare system. As such, the costs only included payment from the third-party payers. Unit cost was combined with resource use to estimate the average cost per course of treatment ().

Table 4. Cost parameters used in the model.

The average bidding price of brand clopidogrel and the weighted average price of the top three most commonly prescribed aspirins among hospitals in Beijing, including the brand one, were used in the current study. The prices were based on a recent study comparing clopidogrel and aspirin in ChinaCitation16. The drug utilization was adjusted based on treatment compliance as reported in the CAPRIE trialCitation9. The costs associated with treatment of ischemic events were extracted from a recent study on health economic evaluation of clopidogrel for treatment of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome in ChinaCitation17.

Costs associated treatment emergent AEs were not included in the model, as very low frequencies of severe AEs were reported in the trial. In addition, the overall safety profile of clopidogrel was judged to be at least as good as aspirin and any AE-related treatment costs would be cancelled out in the calculation of ICER for clopidogrel.

Sensitivity analyses

Both one-way and probabilistic sensitivity analyses were conducted in order to address the uncertainty in the estimation of model parameters. In the one-way sensitivity analyses, we varied the value of one parameter at a time within 95% confidence intervals of its base case value and examined how the ICERs would vary. To assess the overall uncertainty associated with multiple parameters, the Monte Carlo simulation method with 1,000 iterations was applied to do the probabilistic sensitivity analyses, in which all parameters were randomly sampled from certain distributions simultaneously.

Results

Base case analyses

In patients with pre-existing atherosclerosis, 2 years of treatment with clopidogrel and aspirin would yield total QALYs of 8.776 and 8.576 at associated costs of ¥18,777 ($2,838) and ¥12,302 ($1,859), respectively, resulting in an ICER of ¥32,382 ($4,893) per QALY gained. In patients with PVD, secondary prevention with the same drugs would project to lead to total QALYs of 8.836 and 8.632 at costs of ¥18,518 ($2,798) and ¥12,041 ($1,820), respectively, resulting in a corresponding ICER of ¥31,743 ($4,797) per QALY gained ().

Table 5. Cost-effectiveness analysis results.

In both patient populations, clopidogrel was considered to be cost-effective compared with aspirin as the estimated ICERs were lower than the willingness-to-pay threshold of 3-times GDP per capita in China in 2018 (¥193,932, $29,306).

Sensitivity analysis

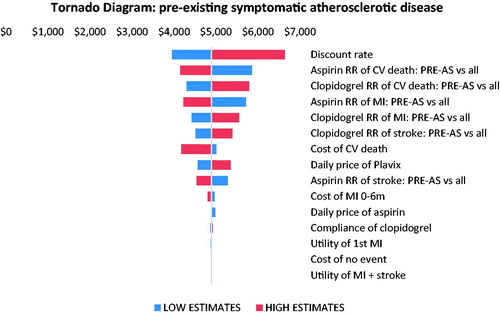

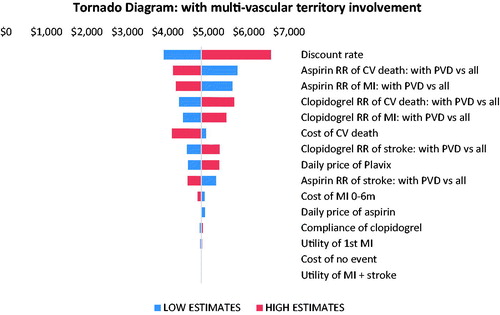

Findings from the one-way sensitivity analyses are displayed in the tornado diagrams ( and ). In both patient groups, the discount rate was the most important driver of cost-effectiveness estimate. The model outputs were also sensitive to the relative risks and their 95% confidence intervals of CV death and MI associated with pre-existing atherosclerosis or PVD, respectively.

Figure 2. One-way sensitivity analysis tornado diagram for PAD with the pre-existing symptomatic atherosclerotic disease sub-population. Abbreviations. RR, relative risk; CV, cardiovascular; PRE-AS, pre-existing symptomatic atherosclerotic disease; MI, myocardial infarction.

Figure 3. One-way sensitivity analysis tornado diagram for PAD with a multi-vascular territory involvement sub-population. Abbreviations. RR, relative risk; CV, cardiovascular; PVD, polyvascular disease; MI, myocardial infarction.

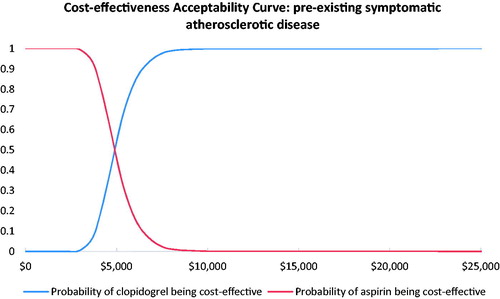

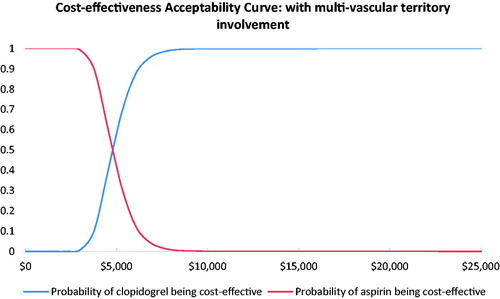

Results from the probabilistic sensitivity analyses are displayed in the cost-effectiveness acceptability curves ( and ). These curves indicate the probability that clopidogrel is cost-effective relative to aspirin at different willingness-to-pay thresholds per QALY gained. The results showed that clopidogrel had a probability of 100% being cost-effective vs aspirin at the willingness-to-pay threshold of 3-times the GDP per capita in China.

Discussion

In patients with pre-existing symptomatic atherosclerosis or PVD, our model projected that 2-year treatment with clopidogrel instead of aspirin would result in an incremental gain of 0.200 and 0.204 QALYs at additional costs of ¥6,475 ($978) and ¥6,477 ($979), respectively. The corresponding ICERs were estimated to be at ¥32,382 ($4,893) and ¥31,743 ($4,797) per QALY gained, which is much lower than the willingness-to-pay threshold of 3-times GDP per capita in China in 2018 (¥193,932, $29,306). In fact, the estimated ICERs were even below the threshold of 1-time GDP per capita. The model was generally robust and clopidogrel had a probability of 100% of being cost-effective in both high risk patient groups with established PAD compared with aspirin in this setting.

CVD remains one of most important threats to public health in China, with an estimated 230 million CVD patients and 3 million deaths due to CVD each year, accounting for 41% in totalCitation8. While CVD manifests in different ways clinically and patients could experience various clinical sequelae, atherothrombosis is a frequent common underlying condition leading to ischemic events and premature death. The CAPRIE trial demonstrated that, compared with aspirin, patients with PAD appeared to benefit most from clopidogrel treatment with a large relative risk reduction compared with patients with recent IS or MI (23.8% vs 7.3% and 3.7%, respectively). As PAD remains a major public health burden and both clopidogrel and aspirin are recommended in current treatment guidelines for secondary prevention in PAD patients in China, we opted to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of clopidogrel vs aspirin in high risk patients with established PAD. We rationed that clopidogrel should have greater health economic advantages in treating high risk patients with established PAD owing to the superior clinical efficacy.

Previously, data from the CAPRIE trial have been subject to several health economic evaluations in western countries comparing clopidogrel with aspirin for the secondary prevention of ischemic events in patients with atherothrombosis including German, Greek, Belgian, and Swedish settingsCitation11,Citation18–20. All studies concluded that use of clopidogrel was cost-effective in patients who met the criteria for the CAPRIE trial. However, these studies did not examine the sub-group population with PAD, despite findings from the CAPRIE trial pointing to the heterogeneous benefits of treatment with clopidogrel. Another cost-effectiveness study using discrete-event simulation evaluated the secondary prevention with clopidogrel in patients with recent IS or established PAD based on the results of the CAPRIE study in the Chinese settingCitation21. The model showed that, compared with aspirin, clopidogrel yielded a net gain of QALYs by 0.21 at an ICER of $US 9,890 per QALY gained in patients with established PAD. Despite our study using a different modeling method, our model projected nearly identical net QALYs gains but with a more favorite cost-effectiveness profile; the ICERs from our model were about a half of the previous study. The difference was likely explained by longer clopidogrel utilization in the previous study (3 years instead of 2 years in our model) and we also modeled high risk patients with established PAD instead of all PAD meeting the criteria for the CAPRIE trial. It is plausible and reasonable that clopidogrel is more cost-effective when used in high risk patients with established PAD.

The Chinese pharmaceutical market differs from western countries in a number of ways. One of the most striking differences is that most brand products continue to maintain their market share in the face of generic entry and this observation holds true for both brand clopidogrel and aspirin, which are widely prescribed in Chinese clinical practice in spite of available generics. For example, among all hospitals in Beijing, the brand aspirin accounted for 92% among the top three prescribed aspirins.

The strength of our study primarily lies with the application of its well-established model structure previously developed based on the CAPRIE trial and at different settingsCitation11,Citation13,Citation14. Having had access to patient level data and conducted detailed analysis in high risk patient groups is another unique feature of our study. We employed a 6-month cycle length in the model as the risks of atherothrombotic events in the 1–6 month period, 7–12 month period, and subsequent months had a noticeable difference in the CAPRIE trial.

Our study also has a number of limitations. The determination of clinical benefit of clopidogrel for treating high risk patient with established PAD was not a pre-specified hypothesis in the CAPRIE trial, rather a post-hoc analysis. As such, the estimated clinical effectiveness in the high-risk patient groups should be viewed in the context of limitations of post-hoc analysis. Nevertheless, the post-hoc analysis of the CAPRIE trial offered the best source of data for the model parameters. Another limitation is that we did not explicitly include the cost associated with treatment emergent AEs. This omission, however, would not materially affect the study conclusions as there were no major differences in terms of safety between the two therapies, and most bleeding events were mild in the CAPRIE trial. Not having costs of severe AE included in the model may under-estimate the cost-effectiveness advantages of clopidogrel as fewer clopidogrel-treated patients had any severe bleeding disorders compared to aspirin-treated patients (1.38% vs 1.55%) in the CAPRIE trial. Lastly, our model assumed the treatment duration lasted only 2 years. In the real world setting, antiplatelet treatment is expected to be beyond this time-limited period. Therefore, since we do not have any clinical outcomes data linking long-term use of clopidogrel beyond 2 years, we cannot project how the long-term treatment may affect its cost-effectiveness profiles.

Conclusions

Secondary prevention with clopidogrel is an attractive cost-effective option at the current willingness-to-pay threshold compared with aspirin for high risk patients with established PAD from the perspective of the national healthcare system in Chinese settings.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Sanofi, China.

Declaration of financial/other interests

XY and LL are full-time employees of Sanofi, China. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Henry Hu for helping with the English language and proofreading the article.

References

- Hirsch AT, Criqui MH, Treat-Jacobson D, et al. Peripheral arterial disease detection, awareness, and treatment in primary care. J Am Med Assoc. 2001;286(11):1317–1324.

- Bhatt DL, Gabriel Steg P, Magnus Ohman E, et al. International prevalence, recognition, and treatment of cardiovascular risk factors in outpatients with atherothrombosis. J Am Med Assoc. 2006;295(2):180–189.

- Diehm C, Allenberg JR, Pittrow D, et al. Mortality and vascular morbidity in older adults with asymptomatic versus symptomatic peripheral artery disease. Circulation. 2009;120(21):2053–2061.

- Fowkes G, Fowkes FGR, Murray GD, et al. Ankle brachial index combined with Framingham risk score to predict cardiovascular events and mortality: a meta-analysis. J Am Med Assoc. 2008;300(2):197–208.

- Allison MA, Ho E, Denenberg JO, et al. Ethnic-specific prevalence of peripheral arterial disease in the United States. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(4):328–333.

- Sebastianski M, Makowsky MJ, Dorgan M, et al. Paradoxically lower prevalence of peripheral arterial disease in South Asians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart. 2014;100(2):100–105.

- Wang Y, Li J, Xu Y, et al. Prevalence of peripheral arterial disease and correlative risk factors among natural population in China. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2009;37(12):127–131.

- Li H, Ge J. Cardiovascular diseases in China: current status and future perspectives. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2015;6:25–31.

- CAPRIE Steering Committee. A randomised, blinded, trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE). CAPRIE Steering Committee. Lancet (London, England). 1996;348:1329–1339.

- Ringleb PA, Bhatt DL, Hirsch AT, et al. Benefit of clopidogrel over aspirin is amplified in patients with a history of ischemic events. Stroke. 2004;35(2):528–532.

- Logman JFS, Heeg BMS, Herlitz J, et al. Costs and consequences of clopidogrel versus aspirin for secondary prevention of ischaemic events in (High-Risk) atherosclerotic patients in Sweden: a lifetime model based on the CAPRIE trial and high-risk CAPRIE subpopulations. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2010;8(4):251–265.

- Chinese Society of Cardiology of Chinese Medical Association, Editorial Board of Chinese Journal of Cardiology. Expert consensus of antiplatelet therapy in cardiovascular disease. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2013;41:183–194.

- Olsen J, Heeg B, Van Gestel A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of clopidogrel vs. aspirin treatment in high-risk acute coronary syndrome patients in Denmark. Ugeskr Laeger. 2006;168(35):2911–2915.

- Heeg BMS, Peters RJG, Botteman M, et al. Long-term clopidogrel therapy in patients receiving percutaneous coronary intervention. Pharmacoeconomics. 2007;25(9):769–782.

- Caro JJ, Ishak KJ, Migliaccio-Walle K. Estimating survival-for cost-effectiveness analyses: a case study in atherothrombosis. Value Health. 2004;7(5):627–635.

- Zhang L, Lin Z, Yin H, et al. Clopidogrel versus aspirin for the treatment of acute coronary syndrome after a 12-month dual antiplatelet therapy: a cost-effectiveness analysis from China payer ‘s perspective. Clin Ther. 2018;40(12):2125–2137.

- Cui M, Tu CC, Chen EZ, et al. A cost-effectiveness analysis of clopidogrel for patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome in China. Adv Ther. 2016;33(9):1600–1611.

- Berger K, Hessel F, Kreuzer J, et al. Clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients with atherothrombosis: CAPRIE-based calculation of cost-effectiveness for Germany. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(1):267–274.

- Kourlaba G, Fragoulakis V, Maniadakis N. Clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients with atherothrombosis: a CAPRIE-based cost-effectiveness model for Greece. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2012;10(5):331–342.

- Annemans L, Lamotte M, Levy E, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients with atherothrombosis based on the CAPRIE trial. J Med Econ. 2003;6(1–4):55–68.

- Li T, Liu M, Ben H, et al. Clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients with recent ischemic stroke and established peripheral artery disease: an economic evaluation in a Chinese setting. Clin Drug Investig. 2015;35(6):365–374.