Abstract

Introduction: Matching available mental health services to patients’ preferences, as well as is possible, may increase patient satisfaction and help increase adherence to certain treatments. This study systematically reviewed discrete-choice experiments (DCEs) on patients’ preferences for treatment of depressive and anxiety disorders and assessed the relative importance of outcome, process and cost attributes to improve the current and future treatment situations.

Methods: A systematic literature review using PubMed, EMBASE and PsychInfo was conducted to retrieve all relevant DCEs published up to 15 April 2019, eliciting patient preferences for treatment of depressive and anxiety disorders. Data were extracted using an extraction sheet, and attributes were classified into outcome, process and cost attributes. The relative importance of each attribute category was then assessed, and studies were evaluated according to their reporting quality, using validated checklists.

Results: A total of 11 studies were identified for qualitative analysis. All studies received an aggregate score of 4 on the five-point PREFS checklist (Purpose, Respondents, Explanation, Findings and Significance). Most attributes were outcome related (52%), followed by process (42%) and cost (6%) attributes. Comparing the attribute categories and summing up the relative importance weights for each category within the studies, process attributes were ranked as most important, followed by cost and outcome attributes.

Conclusions: In this systematic review, heterogeneous results were observed regarding the inclusion and framing of different attributes across studies. Overall, patients considered process and cost attributes to be more important than outcome attributes. Outcomes and process are important for patients, and thus clinicians should be particularly aware of this and take patients’ preferences into account, although the attribute importance may depend on chosen attributes and related levels.

Introduction

Mental disorders are associated with a range of symptoms leading to significant impairments and disability in daily life, resulting in high costs for both individuals and societyCitation1. Due to demographic changes and longer life expectanciesCitation2, the (long-term) consequences and burden of mental disorders are expected to increase in the futureCitation3. This will significantly impact health and major social and economic consequences globallyCitation4. Among all mental illnesses, depressive and anxiety disorders present the highest prevalence worldwideCitation5, estimated at 4.4% and 3.6%, respectivelyCitation6. Thus, they are a leading cause for global disabilityCitation7,Citation8, significantly contributing to the global burden of diseasesCitation3. Anxiety and depressive disorders together account for 12 billion days of lost productivity annually worldwide, at estimated cost of US $925 billionCitation9; therefore, they are among the most expensive disorders worldwideCitation10,Citation11. Anxiety and depressive disorders are a significant burden not only to society, but also to the affected individualCitation12,Citation13.

According to European estimatesCitation14,Citation15, about 48% of affected patients among the European population remain untreated due to low capacities for treatment and low recognition rates of mental problemsCitation15. In Germany, it has been estimated that due to an undersupply of psychological treatment, only 50% of patients with affective disorders and 43% of patients with anxiety disorders are treatedCitation16; in 2003, waiting times for inpatient treatment have been on average 4.6 monthsCitation17. Although the situation has improved after reformation of the psychotherapy guidelines in 2017, waiting times for psychological treatment are still long, due to a lack of psychotherapists and wrong assumptions concerning the demand, leading to a low density of supply in some areasCitation18. Longer waiting times may lead to a higher percentage of patients who do not start therapy at all and remain untreatedCitation19.

Increasingly, policy makers emphasize the role of patient involvement in the evaluation of healthcare interventionsCitation20, as this has been associated with improved health outcomesCitation21. Insights into patients’ preferences and involving patients in the determination of best care may lead to clinical, licensing, reimbursement, and policy decisions that better reflect patient valuesCitation22, thereby increasing patients’ treatment satisfactionCitation23. Unmet preferences can partly explain sub-optimal uptake and adherence to treatment for anxiety and depressive disordersCitation24. Accordingly, patient preferences could help overcome the treatment gap by guiding policy decisions and designing new healthcare programs, leading to improved adherence and decreased dropouts during treatmentCitation11,Citation25,Citation26.

In order to obtain insight into patients’ preferences, discrete-choice experiment (DCE) has been gaining popularity in recent yearsCitation27. This choice modeling method helps to adapt healthcare services to patients’ preferences and provides information on the acceptance of healthcare products and services and on future demandCitation28. A DCE is conducted in a controlled experimental framework in which respondents have to make choices between hypothetical alternatives; their responses are used to calculate choice probabilities and weigh attributesCitation29. Respondents choose the preferred treatment option within a series of hypothetical choice tasks presenting two or more alternatives, described in terms of attributes, each of which has a set of levelsCitation30. DCEs can be used to assess the relative importance of attributesCitation31; these can be divided into three main categories: outcome attributes (e.g. effectiveness, side-effects), process attributes (e.g. treatment type), and cost attributesCitation32.

The increased interest in preference studies, alongside the unmet need for mental health care, has led researchers to conduct several DCE studies in the field of anxiety and depression. To our knowledge, no overview and synthesis of these studies are currently available. Therefore, the aim of this study is to systematically review DCEs eliciting patient preferences for treatment of anxiety and depressive disorders, assessing their quality and evaluating the importance of different attributes.

Methodology

We conducted a systematic review of published DCEs, which assessed treatment preferences of patients suffering from anxiety disorder or depression. This review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) StatementCitation33. The approach was adapted as had already been done in similar reviewsCitation34, using the following headings: (1) eligibility criteria, (2) search strategy, (3) study identification and selection, (4) data extraction and analysis and (5) quality assessment.

Search strategy

The search strategy of this research is based on previous systematic reviews of DCEs in health care by Bekker-Grob et al.Citation35, Clark et al.Citation27 and Soekhai et al.Citation36 It followed a two-stage process composed of (1) a systematic electronic database search in MEDLINE via PubMed (1966–present), EMBASE via Ovid (1974–present) and PsychInfo (1967–present) and (2) an unsystematic scanning of Google Scholar and reference lists of included articles and other reviews on DCEsCitation27,Citation35–37. The last search was run on 16 April 2019.

Search terms for DCEs were based on previous reviewsCitation27,Citation35,Citation36 and included terms for DCEs such as “conjoint analysis”, “conjoint measurement”, “conjoint studies”, “conjoint choice experiment”, “part-worth utilities”, “functional measurement”, “paired comparison”, “pairwise choices”, “discrete choice experiment”, “discrete choice model(l)ing”, “discrete choice conjoint experiment” and “stated preference”. These terms were combined with subject headings and free text terms for “depression” and “anxiety”. Respective MeSH-terms for MEDLINE and PsychInfo, and EMTREE-terms for EMBASE were used to include all synonyms for DCEs and depression or anxiety treatment. The full electronic search strategy for both databases is displayed in Supplementary Material, Appendix A.

Eligibility criteria

Based on previous reviewsCitation27,Citation35,Citation36, studies measuring stated preferences using DCEs or (adaptive) conjoint analyses for the treatment of depressive and anxiety disorders were thus included. The mental disorders were defined using the ICD-10 classifications F31–F34, F40 and F41Citation38 (Supplementary Material, Appendix A). To cover all relevant treatments, all treatment approaches were considered if they aimed to treat the disorder, improve the quality of life for the patient, or support daily life and self-management. Only studies about the preferences of diagnosed patients or the parents of affected children were included. Studies addressing dental anxiety or perinatal depression were excluded, since common treatment patterns differ considerably from general anxiety and depression treatment.

As this research focuses on original DCEs and conjoint analyses, studies using multi-criteria decision methods, other preference elicitation methods or reviews were excluded. There was no country or publication year restriction, and studies needed to be available in English, German, Dutch or French.

Study identification and selection

The study identification and selection process followed the PRISMA flow diagramCitation33 and was conducted by two independent researchers (MT and VV) in a two-stage process. First, after duplicates were removed, titles and abstracts were screened according to the predefined eligibility criteria. Second, the full text of identified studies was assessed, and ineligible studies were excluded according to the predefined eligibility criteria. If a full text was unavailable, the corresponding author was contacted by email. In case of disagreements between the two researchers during the study selection process, consensus was achieved by discussion with a third researcher (MH).

Data extraction and analysis

Data extraction and analysis were conducted in five steps. First, general study characteristics of included DCEs were summarized in a data extraction sheet (Supplementary Material, Appendix B). Extracted items included first author, year of publication, study objective, country, disease of interest, target population, sample size and number of attributes and levels. Second, attributes were classified into three categories (outcome, process and cost) and sub-categories (efficacy, side-effects and treatment duration for outcome attributes, and treatment type, location, frequency, modality, patient-centeredness, waiting times and other treatment aspects for process attributes). Attributes were classified according to the German treatment guidelines for depressionCitation39, which defines five treatment goals: (1) symptom relief and complete remission, (2) reduced mortality, (3) recovery of occupational and psychosocial capability, (4) achievement of mental balance and (5) reduced likelihood of relapsesCitation39 (p. 45 of reference 39). If an attribute could be defined along those goals, it was considered an efficacy attribute. The remaining attributes (especially process attributes) were either classified as within the studies themselves or allocated based on Schaarschmidt et al.Citation32 In case of any doubts regarding the attribute classification, a second researcher (VV) was consulted. Third, information on survey preparation and administration, including attribute and level identification, selection and labeling, and the mode of survey administration were assessed and summarized in the data extraction sheet. Fourth, studies were grouped according to their attribute categories (e.g. studies including outcome attributes only). Saliences regarding the number of attributes and levels, survey preparation and administration practices and relative importance were summarized in a descriptive table. Last, the relative importance of attributes was assessed by estimating the frequency of each attribute category and subgroup and identifying the most important attribute in each study. The relative importance was either directly available and taken from the respective study or, if coefficients for attribute levels were provided, calculated using the level range method as proposed by the ISPOR (International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research) Conjoint Analysis Good Research Practices Task ForceCitation40. Within this method, the difference between the highest and the lowest level coefficient of the same attribute provides the attribute-specific level range. The overall relative importance across all attributes is then calculated by dividing this range by the sum of all attribute level ranges. Therefore, the relative importance depends on the included levels and attributes of the respective studyCitation40. To gain more insight into relative importance measures, studies were divided into sub-groups depending on whether they mainly reported outcome attributes or process attributes. If studies did not provide any data on relative importance or level coefficients, they were excluded from the relative importance analysis.

Quality assessment

Reporting the quality assessment of included studies was conducted by two independent reviewers (MT and VV or MH) using the PREFS checklist as a main toolCitation41. This checklist uses the following five items: Purpose, Respondents, Explanation, Findings and Significance. These include a well-defined study aim in relation to preferences (purpose), sufficient information on participants (respondents), clearly explained methods for measuring preferences (explanation), valid results (findings) and statistical analyses to underline the results (significance). Each item was assessed with a binary score (0 or 1) and summed up to an overall score (from 0 to 5) for each study, which was compared across studies. In addition, studies were evaluated with the ISPOR checklistCitation22, which addresses 10 items concerning the reporting quality of studies, with regard to the research question, attributes and levels, construction of tasks, experiment design, preference elicitation, instrument design, data collection plan, statistical analyses, results and conclusions, and study presentation. All items were evaluated, but data on “attribute and level identification” and “data collection” were further analyzed as part of data analysis, as attribute identification and selection are important for achieving valuable results, and therefore influence the validity and reliability of a DCECitation42–44, but are often poorly reportedCitation43. Chosen attributes considerably affect participants’ choice, as well as related relative importance measuresCitation42. The items from the ISPOR checklist were rated positively if the study described and mentioned them.

Results

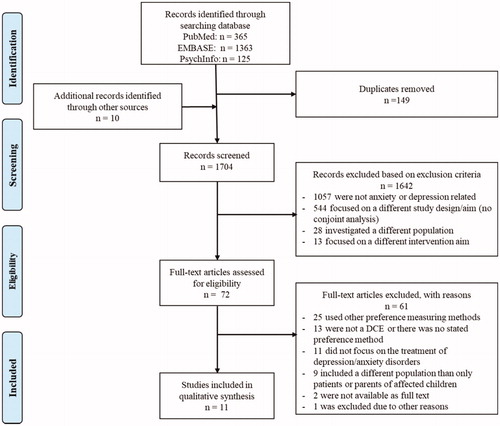

presents an overview of the study selection process according to the PRISMA flow diagramCitation33. The electronic database search of MEDLINE, EMBASE and PsychInfo provided a total of 1,853 records, from which 149 duplicates were removed. Of the remaining 1,704 records, 1,642 were excluded in the title/abstract screening. Ten additional records were identified through a hand search of reference lists and online documents. In the full text assessment of 72 articles (62 remaining articles from database search +10 additional articles), another 61 records were excluded. A total of 11 studies were thus identified for inclusion in the review.

Study characteristics

provides an overview of the most important study characteristics; detailed information can be found in Supplementary Material, Appendix B. Most studies were conducted in the United StatesCitation43–48 and the NetherlandsCitation24,Citation49–51 and one study is from GermanyCitation52.

Table 1. Descriptive study characteristics.

Sample sizes within the studies ranged from 42Citation43 to 469 participantsCitation46, with an average of 210 participants per study (). All participants were diagnosed adult patients. In total, all studies included 67 attributes with an average of 6.09 attributes per study. Six studies focused on measuring preferences onlyCitation24,Citation44,Citation48,Citation50–52, whereas the others also reported on additional aims.

Quality assessment

The quality assessment according to the PREFS-checklistCitation41 is provided in . All studies reported on the purpose, explanation, findings and significance of the study; but only, one studyCitation47 reported on the differences between responders and non-responders.

Table 2. Quality assessment according to PREFSCitation41.

Three studies reported information on each item of the ISPOR-checklistCitation24,Citation49,Citation50,Citation52. All studies had a well-defined research question (item 1), reported on attribute identification and selection (item 2), provided sufficiently detailed results (item 9), and presented them clearly (item 10). Dwight-Johnson et al.Citation43 was the oldest included study, also the shortest, and had the least methodological explanation. The more recent the study, the methodological part was better described. The items most frequently lacking within the ISPOR-checklist were item 3 (construction of tasks), item 4 (experiment design), item 5 (preference elicitation), item 6 (data collection instrument), and item 7 (data collection), whereas the remaining items were described in more detail.

Survey preparation and administration

Attribute and level identification, selection and labeling

Results regarding survey preparation and administration practices are provided in Supplementary Material, Appendix C. All studies, except Morey et al.Citation47 described methods for attribute and level identification. For attribute development, most studies (73%) conducted a literature search of existing studies or package insertsCitation24,Citation44–46,Citation48,Citation50,Citation51, followed by building focus groups (36%)Citation43,Citation45,Citation48,Citation51,Citation52. Eighteen percent explicitly mentioned that focus groups included patientsCitation48,Citation51. Most studies combined several of these methodsCitation46,Citation48,Citation51,Citation52.

The majority of studies (55%) did not distinguish between identification and selection of attributes and levelsCitation43,Citation45–47,Citation49,Citation51. For those studies, it was assumed that the same methods for identification and selection were used. Forty-five percent of the studies provided a separate description for attribute selection following the identification processCitation24,Citation44,Citation48,Citation50,Citation52. Selection of attributes was done mostly by consulting expertsCitation24,Citation44,Citation50,Citation52.

Two studiesCitation24,Citation47 showed inconsistency in attribute labeling, using different terms for the results and analysis description than were within the actual choice tasks.

Mode of survey administration

Sixty-four percent of the studies used an online questionnaireCitation24,Citation46,Citation48–52; one of these studies conducted personal interviews additionallyCitation51. Interviewer-led surveys were conducted by three studiesCitation45,Citation47,Citation51. Two studies did not describe the mode of survey administrationCitation43,Citation44.

Attribute classification

The number of attributes included within the studies () ranged from 3 to 10. Most studies included four attributesCitation24,Citation44,Citation45,Citation50. summarizes the attributes classified among all studies. Two studiesCitation47,Citation49 combined all three attribute categories. Six studies (33%) included outcome attributes, eight studies (45%) process attributes and four studies (22%) used cost attributes. Supplementary Material, Appendix D provides an overview of all classified attributes and corresponding studies.

Table 3. Data extraction and attribute classification of DCEs about anxiety and depression.

Outcome attributes

Twenty of the 35 included outcome attributes (57%) were related to side effectsCitation46–48,Citation51,Citation52, which was therefore the most commonly considered sub-class within the outcome attribute category. “Weight gain” was the most often included attribute side effectCitation46–48,Citation51, followed by attributes concerning decreased libidoCitation47,Citation51. Other outcome attributes relating to side effects were diverse. Efficacy attributes (37%), which were included by six studiesCitation46–49,Citation51,Citation52 were variously framed, including positive and negative framings. The remaining two outcome attributes (6%) were related to treatment duration and included by two studiesCitation51,Citation52.

Process attributes

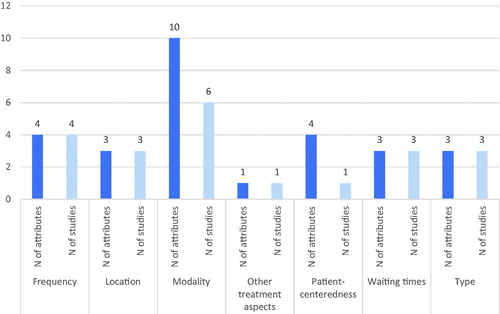

In contrast to the outcome attributes, the process attributes (n = 28) were framed similarly across studies. Attributes were sub-classified into attributes concerning treatment modality, treatment frequency, patient centeredness, location of treatment, waiting times and treatment type. Modality attributes related either to the format of treatment, meaning the distinction between individual or small/large group treatmentCitation24,Citation43,Citation45,Citation50 or to “level of digitalization”Citation24,Citation50, “vision of treatment”Citation49 and “intake and care plan”Citation49. Frequency attributes described varying levels from weekly to monthly meetingsCitation24,Citation44,Citation47,Citation50. Attributes regarding patient-centeredness (n = 4) were all included by the same studyCitation49. Attributes regarding “location of treatment” (n = 3)Citation43–45, “waiting times” (n = 3)Citation24,Citation49,Citation50 and “treatment type” (n = 3)Citation43–45 were defined similarly across studies. Location attributes distinguished between “treatment at home”, in “primary care setting” or “at a mental health clinic”Citation43–45. Waiting times ranged from one to 24 weeksCitation24,Citation49,Citation50, and treatment types were described as “counseling”, “medication” or a “combination of both”Citation43–45. One process attribute was allocated to “other treatment aspects”Citation51.

Cost attributes

Four studies included cost attributesCitation44,Citation45,Citation47,Citation49, either regarding monthly costsCitation44,Citation45 or cost per consultationCitation49.

Sub-group analysis

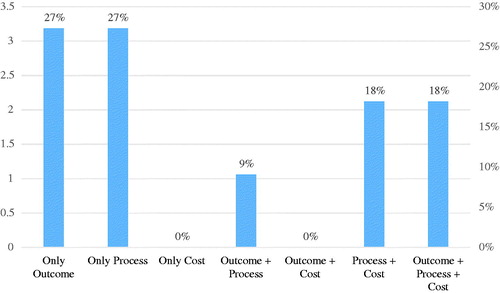

Six studies included outcome, eight studies included process, and four studies cost attributes. provides a more detailed overview regarding which combinations of attribute categories (outcome, process, cost) were used and in how many studies.

Figure 2. Amount and percentage of studies including the respective combination of attribute categories (all studies n = 11).

Four studies were grouped into the sub-group “outcome-attribute-studies”Citation46,Citation48,Citation51,Citation52 of which one study included one process attribute in addition to the outcome attributesCitation51 and was therefore considered to be part of this sub-group. Outcome attributes relating to side effects were included more often than efficacy or treatment duration attributes. For attribute identification, all studies used literature search or expert consultation in first place. Further, attributes were identified via focus groupsCitation48,Citation51,Citation52 and patient interviewsCitation46. Attribute and level selection were either not separately describedCitation46,Citation51 or conducted by expert consultationCitation52 or qualitative research, including patient interviewsCitation48.

Eight studies included process attributesCitation24,Citation43–45,Citation47,Citation49–51, of which three did not include any other attribute categoryCitation24,Citation43,Citation50. presents the allocation of process attributes to sub-classes and the number of studies including the respective attribute category.

Figure 3. Amount of process attributes within the respective sub-classification and number of studies including the sub-class of process attributes.

Four studies included a cost attributeCitation44,Citation45,Citation47,Citation49, mainly next to process attributes. All cost attributes had three relating levels describing either cost per monthCitation44,Citation45 or cost per consultationCitation49.

Relative importance

Ten studies were included in the relative importance analysis. One studyCitation47 was excluded since it reported neither level coefficients nor attribute weights, which made it impossible to calculate the relative importance of attributes. An overview of the relative importance scores per study is provided in Supplementary Material, Appendix E.

shows the number of times an attribute category was considered most important in relation to the total number of times the respective attribute category was included in all studies. If attributes were considered individually, cost attributes were ranked as most important attribute most often relative to the total amount of included cost attributes, followed by process- and outcome attributes. To compare the attribute categories, we summed up all relative importance weights of one attribute category within studies including more than one attribute category. Considered in total, the sum of all relative weights relating to process attributes was most important in six out of 10 studies, followed by the sum of outcome attributes weights in four studies. Cost attributes, when compared to the sum of process and outcome attribute weights, were of lower importance.

Table 4. Number of times an attribute classification was most important.

Outcome attributes

Four studies considered an outcome attribute as the most important attributeCitation46,Citation48,Citation51,Citation52. Three of them related to side effects, of which two described “weight gain”Citation46,Citation48 and one “intestine and stomach complaints”Citation51; although, this was the only study including this specific attribute. In the respective studyCitation51, “weight gain” was ranked the second most important attribute. The attribute “weight gain” was described with similar levels ranging from no weight gain to more than 20 lbsCitation46,Citation48, whereas less weight gain was preferred by the participants. One study considered an efficacy outcome attribute as most importantCitation52, which was described as “loss of energy/fatigue”, with three levels relating to the daily-life capabilities of depressed patients. This study did not include the side-effect attribute relating to weight gain. Studies considering an outcome attribute as most important did not include any process or cost attributes except for Wouters et al.Citation51, which included “other treatment aspects” only as a process attribute.

In general, outcome attributes were described diverse, which made it difficult to compare relative importance weights across studies. “Weight gain” and “treatment duration” were mentioned by several studies while other attributes were framed differently. In general, side-effect outcome attributes were considered as most important more often than efficacy attributes.

Process attributes

Process attributes were ranked as most important by four studiesCitation24,Citation43,Citation45,Citation50. In two of these, process attributes were related to “modality”Citation24,Citation50. These two studies were identical, one addressing depressiveCitation24 and the other one anxiety disordersCitation50, and did not include any outcome or cost attributes. The respective modality attribute was described as “level of digitalization”, meaning whether the treatment is administered face-to-face, digitally, or both combined (participants preferred face-to-face treatment)Citation24,Citation50. Those studies were the only ones including this specific modality attribute. The other two most important process attributes addressed “treatment type”Citation43,Citation45, described as the choice between “counseling”, “medication” or a combination of both. Both studies were conducted by the same author and did not include any outcome attributes. Dwight-Johnson et al.Citation45 also included a cost attribute, which was ranked second most important. The studies of Dwight-Johnson et al.Citation43–45 were the only studies including the process attribute “treatment type”.

In general, process attributes were ranked most important more often than outcome attributes. The process attributes ranked most important were each considered to be so by the same author: Lokkerbol et al.Citation24,Citation50 for modality attributes and Dwight-Johnson et al.Citation43,Citation45 for treatment type. Other process attribute sub-classes, which were included in other studies (frequency, location, waiting times, and modality relating to group size) were not considered as most important once.

Cost attributes

Three studies included a cost attribute, of which two ranked this attribute as most importantCitation44,Citation49. One study described “costs per consultation” with category levelsCitation49 and the other one “costs per month” with continuous levelsCitation44. Both studies included, along with the cost attribute mainly other process attributes.

Cost attributes are considered most important more often in relation to their total amount than outcome attributes, although Groenewoud et al.Citation49 is the only study including both attribute categories. Cost attributes also seem more important than process attributes, except for Dwight-Johnson et al.Citation44, who ranked the process attribute “treatment type” more important than costs. Cost attributes were ranked most important if regarded individually. In comparison with the sum of all the relative importance weights of each attribute category, process attributes were ranked more important.

Discussion

This systematic review identified 11 DCEs on the treatment preferences of depressive and anxiety disorders. All studies investigated the preferences of adult patients either in primary or inpatient care. Only one DCE assessing treatment preferences for anxiety disorders was identifiedCitation50, the remaining studies focused on various types of depression including bipolar disorders. The results of the study synthesis were heterogeneous, especially regarding the inclusion of attributes and related levels. Overall, outcome attributes were investigated most often, but were described in diverse ways across studies. Outcomes attributes regarding efficacy were rarely used across studies and were formulated imprecisely. Although efficacy measurements should be the main focus as to why patients start a therapy, studies offered very little consideration of what patients want to achieve with their therapy.

We could not observe any clear tendency or standard regarding the amount of attributes to include in a DCE, as the number of included attributes varies across studies; this corresponds with other reviewsCitation27,Citation34,Citation36.

The analysis of relative importance showed a high importance for cost attributesCitation44,Citation45,Citation49, which could relate to the high deductibles patients have to pay within the countries investigated. The high importance of process attributes, in particular attributes relating to treatment modality and typeCitation24,Citation43,Citation45,Citation50, shows that how a therapy is conducted seems more important to patients than the actual outcome of their therapy. This is supported by the importance ranking of outcome attributes, which were considered as most important only if no cost or process attribute was included in the respective studies. Within outcome attributes, side-effects seem more important to patients than efficacy measurements, supporting the above-mentioned statement that the actual outcome of the therapy seems less important to patients. The rather low importance of outcome attributes, especially of those relating to efficacy, could also relate to the imprecise framing and the difficulty of measuring efficacy within mental health.

Due to the heterogeneous results and some identified shortcomings within the included DCEs, findings from this review should be interpreted with caution. Eleven studies from only three countries are a limited number to analyze, especially taking into account that no restriction regarding the publication year was applied and the number of all DCEs in health care has continuously risen in the past yearsCitation35,Citation36. The overall reporting quality was acceptable but leaves some room for improvement. Only one study achieved the full score on the PREFS checklist. None of the other studies reported on differences between responders and non-responders, which could imply a non-response bias within those studies.

The number of included outcome and process attributes was diverse, which may lead to biased results when investigating the relative importance across studies. It is necessary to consider that relative importance based on level ranges (as calculated in this review) is dependent on the included attributes and levels of the studyCitation40. Attribute importance of the same attribute can thus vary in different studies, depending on the selected levelsCitation53. The exactly described and large level range in Ng-Mak et al.Citation48, in contrast to the subjective description in Wouters et al.Citation51, could have caused “weight gain” to be assessed as most important in the first study and in second place in the other study. Inclusion of separate attributes for detailed descriptions of outcomes or processes may also lead to more detailed results than consideration of a generalized attribute like “side effects ongoing after the first two weeks” as in Zimmermann et al.Citation52

The cost attribute was difficult to interpret, as studies did not specify which types of costs were considered. Furthermore, it is difficult to compare costs across countries with different health insurance systems and across diverse populations, due to differences in reimbursement schemes and ability to pay. This may lead to either ignorance or dominance of the cost attribute. Population dependency on the cost attribute could explain the difference in relative importance ranking in the two studies of Dwight-Johnson et al., using a similar experiment design but surveying different target populations. The high importance of the cost attribute across studies should be treated with caution, as it could have been ranked more important as it was defined more clearly and was more comparable across studies in comparison with outcome attributes, which were defined subjectively and varied across studies.

Attribute identification and selection are important for obtaining valuable results; both influence the validity and reliability of a DCECitation42,Citation54,Citation55, but are often poorly reportedCitation54. The specific selection of attributes within a study influences preferences measuresCitation53. An attribute can be of much more importance for participants simply because another attribute has been excluded. It is very important that authors describe the methods applied for attribute identification and selection transparently, and preferably include the patient perspective in these stepsCitation56. Ninety percent of studies used such (mixed) methods, most often reporting literature reviews (73%) for attribute identification. Not considering patients’ opinions may lead to biased results, as patients might find different attributes important. Discrepancies between patients and professionals regarding treatment preferences for depression have also been reported by the German Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Healthcare (IQWiG)Citation57. “Remission” was much more important to experts than to patients, in contrast to “treatment response”. Moreover, “decreased libido” as a side effect was of lowest importance for both groupsCitation57 (p. 21 of reference 57) but is still included in some DCEsCitation47,Citation51. Although 64% of the studies reported on patient inclusion during the attribute identification and 55% during the selection, the accuracy of results could be increased by including patients more often and pre-testing questionnaires with a small patient sample to improve clarity and understanding of choice tasks.

A personal interview, as also recommended by ISPORCitation22, may improve data quality as participants have the possibility to ask questions. Interviewer-led surveys are not always possible due to financial restrictions and large sample sizes; therefore, our review recommends adapting the mode of administration to the target population. Some participants, especially in the field of mental health, where some may have possible cognitive constraints, may need more support than others, e.g. older populationsCitation58.

This review has potential limitations, although it was conducted according to best practices in systematic reviews. First, the above-described limitations of the included studies also limit the validity of the present review, as studies presented potentially biased results, leading in conclusion to unclear review results. Second, this paper includes a limited number of DCEs. Considering only 11 studies from only three different countries, of which only one investigated anxiety disorders, may lead to limitations regarding the generalizability of results. Furthermore, the systematic exclusion of patients with perinatal depression and anxiety leads to another minimization of included studies. Studies addressing patients with perinatal depression were excluded, because the therapy of pregnant and breastfeeding women could vary from non-pregnant patients, as some medications are not suitable for pregnant women. Third, the reporting quality of studies leaves room for improvement, although we did not evaluate the studies’ methodological quality. Fourth, some data were missing, which hindered the calculation of relative attribute importance.

Overall, this review summarizes actual patient preferences in the treatment of depressive and anxiety disorders. Investigated studies do not make any recommendations regarding how the existing treatment gap can be overcome, but reviewing important and non-important attributes helps to adjust existing treatments according to patients’ needs, which may lead to improved adherence. Thus, the results of our study have the possibility to improve treatment efficiency, reduce the treatment gap and help to reduce the overall global burden of depression and anxiety. Studies showed an especially high importance for costs and process attributes; these should be taken into consideration when designing, selecting and assessing interventions.

Still, further research is needed regarding the potential standardization of the number and framing of included attributes and levels in future DCEs addressing depression and anxiety disorders, in order to make studies more comparable and derive practical implications. Only four studies included costs, but two suggested it is important; therefore, more research is needed on the importance and framing of this attribute in studies of mental health care. Last, research in more countries is needed to draw generalizable conclusions for the future treatment of anxiety and depressive disorders.

Conclusions

Our systematic review of DCEs about anxiety and depressive disorders reported heterogeneous attributes and results. The studies included various numbers of attributes for each category (outcome, process and cost) and defined them differently, which made it difficult to compare the attributes. Outcome attributes were included most often, followed by process attributes. Cost attributes were not considered in every study, but were ranked to be most important by patients most often in relation to the total amount of included cost attributes, when looking at attributes individually. When comparing attribute categories by considering the sum of importance weights for one category, process attributes were more important than costs. Clinicians and decision makers should thus be aware that all types of attributes (process, costs and outcomes) can be important for patients, and keep in mind that patients’ choices were dependent on included attributes and levels. Aligning treatment with the patients’ preferences could help to enhance treatment adherence and lead to higher efficiency in mental health care.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

No funding was used for the conduct of this study.

Declaration of financial/other interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

Maike Tünneßen (MT) conducted the systematic review and drafted the manuscript. Vera Vennedey (VV) supported the systematic search for literature, reviewed the study screening, and provided quality assessment of studies. VV and Mickaël Hiligsmann (MH) supported data extraction and interpretation. VV, MH and Stephanie Stock reviewed the manuscript and facilitated the project.

Supplementary Material

Download MS Word (140.4 KB)Tables and Figures

Download MS Word (181.2 KB)Acknowledgements

No assistance is to be declared in the preparation of this article.

References

- NICE. Common mental health disorders: the NICE guideline on identification and pathways to care. Leicester: British Psychological Society; 2011.

- European Commission. Ageing report: policy challenges for ageing societies [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Jan 7]. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/info/news/economy-finance/policy-implications-ageing-examined-new-report-2018-may-25_en

- Trautmann S, Rehm J, Wittchen HU. The economic costs of mental disorders: do our societies react appropriately to the burden of mental disorders? EMBO Rep. 2016;17:1245–1249.

- WHO. Mental disorders [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Jan 11]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-disorders

- Ritchie H, Roser M. Mental health [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Jan 28]. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/mental-health

- WHO. Depression and other common mental disorders: global health estimates (license: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017.

- Eaton WW, Martins SS, Nestadt G, et al. The burden of mental disorders. Epidemiol Rev. 2008;30:1–14.

- Vos T, Allen C, Arora M, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388:1545–1602.

- Chisholm D, Sweeny K, Sheehan P, et al. Scaling-up treatment of depression and anxiety: a global return on investment analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:415–424.

- Baxter AJ, Vos T, Scott KM, et al. The global burden of anxiety disorders in 2010. Psychol Med. 2014;44:2363–2374.

- Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;382:1575–1586.

- NIMH. The National Institute of Mental Health. Anxiety disorders [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Jun 18]. Available from: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/anxiety-disorders/index.shtml

- Sobocki P, Jönsson B, Angst J, et al. Cost of depression in Europe. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2006;9:87–98.

- Alonso J, Codony M, Kovess V, et al. Population level of unmet need for mental healthcare in Europe. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:299–306.

- Thornicroft G, Chatterji S, Evans-Lacko S, et al. Undertreatment of people with major depressive disorder in 21 countries. Br J Psychiatry. 2017;210:119–124.

- Wittchen H-U, Jacobi F. Die Versorgungssituation psychischer Störungen in Deutschland. Bundesgesundheitsblatt – Gesundheitsforschung – Gesundheitsschutz. 2001;44:993–1000.

- Zepf S, Mengele U, Hartmann S. Zum Stand der ambulanten psychotherapeutischen Versorgung der Erwachsenen in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland [The state of outpatient psychotherapy in Germany]. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2003;53:152–162.

- Federal Chamber of Psychotherapists. BPtK-Studie: Ein Jahr nach der Reform der Psychotherapie-Richtlinie – Wartezeiten [Internet]; 2018 [updated 2018 Apr 11; cited 2019 Jun 23]. Available from: https://www.bptk.de/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/20180411_bptk_studie_wartezeiten_2018.pdf

- Foreman DM, Hanna M. How long can a waiting list be? Psychiatr Bull. 2000;24:211–213.

- Dexter PR, Miller DK, Clark DO, et al. Preparing for an aging population and improving chronic disease management. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2010;2010:162–166.

- Greenfield SM, Kaplan S, Ware JE. Expanding patient involvement in care. Effects on patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 1985;102:520–528.

- Bridges JFP, Hauber AB, Marshall D, et al. Conjoint analysis applications in health – a checklist: a report of the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Conjoint Analysis Task Force. Value Health. 2011;14:403–413.

- Umar N, Schaarschmidt M, Schmieder A, et al. Matching physicians’ treatment recommendations to patients’ treatment preferences is associated with improvement in treatment satisfaction. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:763–770.

- Lokkerbol J, Geomini A, van Voorthuijsen J, et al. A discrete-choice experiment to assess treatment modality preferences of patients with depression. J Med Econ. 2019;22:178–186.

- Swift JK, Callahan JL, Vollmer BM. Preferences. J Clin Psychol. 2011;67:155–165.

- Hiligsmann M, Dellaert BG, Dirksen CD, et al. Patients’ preferences for anti-osteoporosis drug treatment: a cross-European discrete choice experiment. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56:1167–1176.

- Clark MD, Determann D, Petrou S, et al. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: a review of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014;32:883–902.

- Mühlbacher A, Bethge S, Tockhorn A. Präferenzmessung im Gesundheitswesen: Grundlagen von Discrete-Choice-Experimenten. Gesundh Ökon Qual Manag. 2013;18:159–172.

- Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care. Allgemeine Methoden: Version 5.0 vom 10.07.2017. Köln; 2017.

- Hazlewood GS. Measuring patient preferences: an overview of methods with a focus on discrete choice experiments. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2018;44:337–347.

- Carson RT, Louviere JJ. A common nomenclature for stated preference elicitation approaches. Environ Resour Econ. 2011;49:539–559.

- Schaarschmidt ML, Schmieder A, Umar N, et al. Patient preferences for psoriasis treatments: process characteristics can outweigh outcome attributes. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1285–1294.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097.

- Bien DR, Danner M, Vennedey V, et al. Patients’ preferences for outcome, process and cost attributes in cancer treatment: a systematic review of discrete choice experiments. Patient. 2017;10:553–565.

- Bekker-Grob EWd, Ryan M, Gerard K. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: a review of the literature. Health Econ. 2012;21:145–172.

- Soekhai V, Bekker-Grob EWd, Ellis AR, et al. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: past, present and future. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019;37:201–226.

- Eiring Ø, Landmark BF, Aas E, et al. What matters to patients? A systematic review of preferences for medication-associated outcomes in mental disorders. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e007848.

- Deutsches Institut für Medizinische Dokumentation und Information (DIMDI) im Auftrag des Bundesministeriums für Gesundheit (BMG) unter Beteiligung der Arbeitsgruppe ICD des Kuratoriums für Fragen der Klassifikation im Gesundheitswesen. ICD-10-GM Version 2019, Systematisches Verzeichnis, Internationale statistische Klassifikation der Krankheiten und verwandter Gesundheitsprobleme, 10. Revision, Stand: 21 Sep 2018; [Internet]; [cited 2019 Jun 2]. Available from: www.dimdi.de

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie, Psychotherapie und Nervenheilkunde, Ärztliches Zentrum für Qualität in der Medizin. S3-Leitlinie/Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinie Unipolare Depression – Langfassung, 2. Auflage. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie, Psychotherapie und Nervenheilkunde (DGPPN); Bundesärztekammer (BÄK); Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KBV); Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF); 2015.

- Hauber AB, González JM, Groothuis-Oudshoorn CMG, et al. Statistical methods for the analysis of discrete choice experiments: a report of the ISPOR Conjoint Analysis Good Research Practices Task Force. Value Health. 2016;19:300–315.

- Joy SM, Little E, Maruthur NM, et al. Patient preferences for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a scoping review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2013;31:877–892.

- Helter TM, Boehler C. Developing attributes for discrete choice experiments in health: a systematic literature review and case study of alcohol misuse interventions. J Subst Use. 2016;21:662–668.

- Dwight-Johnson M, Lagomasino IT, Aisenberg E, et al. Using conjoint analysis to assess depression treatment preferences among low-income Latinos. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:934–936.

- Dwight-Johnson M, Apesoa-Varano C, Hay J, et al. Depression treatment preferences of older white and Mexican origin men. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35:59–65.

- Dwight-Johnson M, Lagomasino IT, Hay J, et al. Effectiveness of collaborative care in addressing depression treatment preferences among low-income Latinos. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61:1112–1118.

- Johnson FR, Ozdemir S, Manjunath R, et al. Factors that affect adherence to bipolar disorder treatments: a stated-preference approach. Med Care. 2007;45:545–552.

- Morey E, Thacher JA, Craighead WE. Patient preferences for depression treatment programs and willingness to pay for treatment. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2007;10:73–85.

- Ng-Mak D, Poon J-L, Roberts L, et al. Patient preferences for important attributes of bipolar depression treatments: a discrete choice experiment. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;12:35–44.

- Groenewoud S, Van Exel NJA, Bobinac A, et al. What influences patients’ decisions when choosing a health care provider? Measuring preferences of patients with knee arthrosis, chronic depression, or Alzheimer’s disease, using discrete choice experiments. Health Serv Res. 2015;50:1941–1972.

- Lokkerbol J, van Voorthuijsen JM, Geomini A, et al. A discrete-choice experiment to assess treatment modality preferences of patients with anxiety disorder. J Med Econ. 2019;22:169–177.

- Wouters H, van Dijk L, Van Geffen ECG, et al. Primary-care patients’ trade-off preferences with regard to antidepressants. Psychol Med. 2014;44:2301–2308.

- Zimmermann TM, Clouth J, Elosge M, et al. Patient preferences for outcomes of depression treatment in Germany: a choice-based conjoint analysis study. J Affect Disord. 2013;148:210–219.

- Lancsar E, Louviere JJ. Conducting discrete choice experiments to inform healthcare decision making: a user’s guide. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26:661–677.

- Coast J, Al-Janabi H, Sutton EJ, et al. Using qualitative methods for attribute development for discrete choice experiments: issues and recommendations. Health Econ. 2012;21:730–741.

- Ryan M, Gerard K. Using discrete choice experiments to value health care programmes: current practice and future research reflections. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2003;2:55–64.

- Louviere JJ, Flynn TN, Carson RT. Discrete choice experiments are not conjoint analysis. J Choice Model. 2010;3:57–72.

- Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care. Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) – Pilotprojekt zur Erhebung von Patientenpräferenzen in der Indikation Depression: Arbeitspapier. Köln; 2013. (IQWiG-Berichte; no. 163).

- Vennedey V, Danner M, Evers SM, et al. Using qualitative research to facilitate the interpretation of quantitative results from a discrete choice experiment: insights from a survey in elderly ophthalmologic patients. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:993–1002.