?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Background and aims: A wide range of treatment options are available for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), including systemic treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) such as sorafenib and lenvatinib, immunotherapies, locoregional therapies such as selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT) and treatments with curative intent such as resection, radiofrequency ablation and liver transplantation. Given the substantial economic burden associated with HCC treatment, the aim of the present analysis was to establish the cost of using SIRT with SIR-Spheres yttrium-90 (Y-90) resin microspheres versus TKIs from healthcare payer perspectives in France, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom (UK).

Methods: A cost model was developed to capture the costs of initial systemic treatment with sorafenib (95%) or lenvatinib (5%) versus SIRT in patients with HCC in Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stages B and C. A nested Markov model was utilized to model transitions between progression-free survival (PFS), progression and death, in addition to transitions between subsequent treatment lines. Cost and resource use data were identified from published sources in each of the four countries.

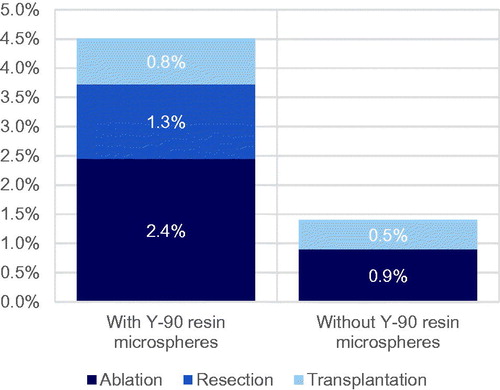

Results: Relative to TKIs, SIRT with SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres were found to be cost saving in all four country settings, with the additional costs of the microspheres and the SIRT procedure being more than offset by reductions in drug and drug administration costs, and treatment of adverse events. Across the four country settings, total cost savings with SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres fell within the range 5.4–24.9% and SIRT resulted in more patients ultimately receiving treatments with curative intent (4.6 vs. 1.4% of eligible patients).

Conclusion: SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres resulted in cost savings relative to TKIs in the treatment of unresectable HCC in all four country settings, while increasing the proportion of patients who become eligible for treatments with curative intent.

Background and aims

World Health Organization (WHO) data for 2018 reported liver cancer to be the sixth most common cancer by worldwide number of incident cases, and the fourth most common cause of cancer-related death, with an estimated 841,080 new cases (representing 4.7% of all incident cancers) and 781,631 deaths (representing 8.2% of all cancer deaths) in 2018Citation1. Worldwide, the age-standardized incidence of liver cancer was 2.8 times higher in men than in women.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common form of primary liver cancerCitation2, and current treatment guidelines recommend that all patients with HCC be evaluated for potentially curative therapies, which include resection, transplantation and, in the case of smaller lesions, ablative therapies such as radiofrequency or cryoablationCitation3. In patients who are not candidates for treatments with curative intent, locoregional therapies should be considered as a treatment option, potentially as part of a strategy to downstage patients to treatments that do have a curative intent.

In 2007, the SHARP randomized controlled trial (RCT) demonstrated the superior efficacy of tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) sorafenib (Nexavari; Bayer AG) versus placebo in patients with advanced HCC in patients who had not received prior systemic therapy, with median overall survival (OS) of 10.7 versus 7.9 months (p < .001)Citation4. Based on the SHARP data, sorafenib became and remains the preferred systemic treatment option in patients with unresectable HCC. Findings of the REFLECT trial were published in 2018, and showed lenvatinib (Lenvimaii; Eisai GmbH), a multireceptor TKI, to be non-inferior to sorafenib in terms of OS (13.6 vs. 12.3 months, hazard ratio: 0.92)Citation5.

As the number of systemic treatment options for unresectable HCC has increased, the evidence base supporting the use of locoregional therapies has also grown. The SorAfenib versus Radioembolisation in Advanced Hepatocellular carcinoma (SARAH) trial was a phase III, open-label RCT in locally advanced or inoperable HCC designed to directly compare the efficacy and safety of SIRT with SIR-Spheresiii yttrium-90 (Y-90) resin microspheres versus sorafenibCitation6. While SARAH showed no difference in median OS (9.9 vs. 9.9 months in patients who ultimately received treatment, p = .92), incidence of all adverse events was 56% lower with SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres than sorafenib (p < .001), objective response rate was 19% with SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres compared with 11.6% in patients treated with sorafenib, and patient quality of life was significantly higher as measured by the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaireCitation6. Furthermore, progression in the liver as the first site was significantly lower with SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres than sorafenib (hazard ratio: 0.72, 95% confidence interval: 0.56–0.93, p = .0143). The SIRveNIB trial, conducted in the Asia-Pacific region, similarly found no significant differences in OS between SIRT with SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres and sorafenib (11.3 months with SIRT compared with 10.4 months with sorafenib in the population who ultimately received treatment in each arm, p = .27)Citation7.

In second-line treatment for patients who had progressed on or were intolerant to sorafenib, trials of brivanib, everolimus, ramucirumab, tivantinib and ADI-PEG 20 had failed to show any benefits over placebo, until the phase III randomized RESORCE trial showed positive results for regorafenib in patients with disease progression on sorafenib, with a median OS of 10.6 versus 7.8 months (p < .0001). The CELESTIAL trial of cabozantinib also then demonstrated improvements in OS relative to placebo in patients with HCC previously treated with sorafenibCitation8.

Given the potential for improved quality of life and an increased proportion of patients ultimately becoming eligible for receiving treatments with curative intent after SIRT, the aim of the present study was to evaluate the cost of using SIRT with SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres as first-line therapy in patients with unresectable HCC compared with TKIs sorafenib or lenvatinib. The focus was on a population of patients with BCLC stage B not eligible for treatment with transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) and eligible patients with BCLC stage C HCC from the perspective of national healthcare payers in four European countries: France, Italy, Spain and the UK (the latter specifically patients covered by the NHS in England).

Methods

Model development

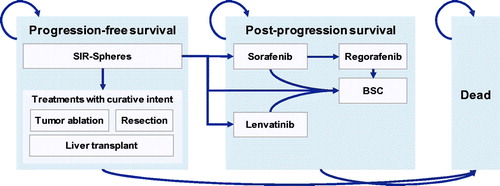

A cost model was developed in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporationiv) to simultaneously model disease progression and progression from first-line treatment to second- and third-line treatments and best supportive care (BSC). The model was structured as a nested Markov model, with the top-level Markov model incorporating states of progression-free survival (PFS), post-progression survival (PPS) and death, and nested models within the PFS and PPS states capturing transitions between subsequent treatments ().

Figure 1. Nested Markov model structure illustrating the top-line transitions from progression-free survival to post-progression survival and death, and nested transitions between treatment lines.

Transitions between the PFS, PPS and death states were modeled using a partitioned survival, area-under-the-curve (AUC) cohort simulation approach. Kaplan-Meier data for PFS and OS were obtained from the per-protocol population in the SARAH RCT and used to fit parametric curves, which then informed the top-level transition probabilities between the PFS, PPS and death statesCitation6. Exponential, generalized gamma, Gompertz, log logistic, lognormal and Weibull fits to the PFS and OS curves were evaluated using the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC), with the lowest scoring (i.e. best fitting) models for PFS and OS selected for use in the base case analysisCitation9,Citation10. Where the model with the lowest AIC was different from the model with the lowest BIC, the lowest sum of AIC and BIC was used to determine the best model fit.

The model reported costs divided across seven categories: implantable device costs (covering the cost of the SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres), hospital care and intervention room costs (covering the costs of the SIRT work-up and treatment), drug costs, adverse event costs, follow-up and drug administration costs, curative intent treatment costs and end of life care costs. In addition to costs, the model also reported the proportion of patients ultimately undergoing treatments with curative intent, the evolution of the use of treatments with curative intent over the time horizon of the analysis and mean life expectancy in years.

Scenarios, time horizon, discounting and analysis perspective

In all four country-specific analyses, all patients eligible for inclusion started in the PFS state on an initial HCC treatment in the two scenarios: sorafenib (95%) or lenvatinib (5%) in the “without SIRT” scenario and SIRT with SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres (100%) in the “with SIRT” scenario. The 95:5 split between sorafenib and lenvatinib in the “without SIRT” arm was based on expert clinical opinion. Analyses were conducted over a three-year time horizon from the perspective of the national healthcare payer in each of the respective countries. The national healthcare payer perspective was adopted in line with guidelines or consensus from the relevant authorities in each country: the Haute Autorité de Santé (HAS) in France, the Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco (AIFA) in Italy, the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) in the UK and the Interministerial Committee for Pricing (ICP) in SpainCitation11–13. No discounting was applied in line with best practice budget impact modeling guidelines from the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research; while the objectives and audience of a budget impact model and a short-term cost model may be different, the omission of discounting results in a simple sum of the predicted costs over a three-year budget period rather than capturing the time preference-adjusted net present value of any future expenditure.

Treatment following progression

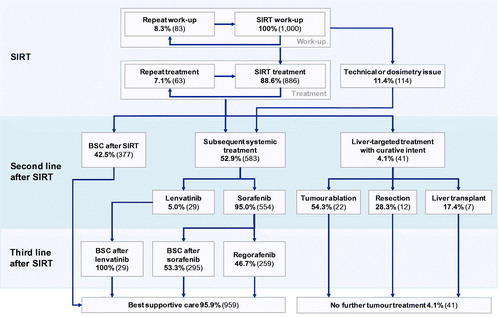

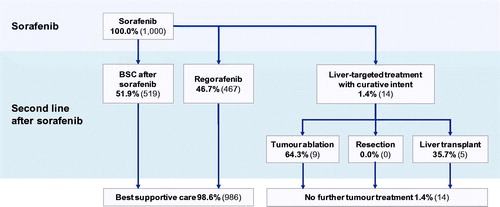

After initial treatment with SIRT or after progression with sorafenib or lenvatinib, the PPS state incorporated a nested Markov model to capture transitions between subsequent systemic treatments or best supportive care (BSC). After SIRT, second-line treatments included BSC, lenvatinib, sorafenib or, within the PFS state, treatments with curative intent (radiofrequency ablation, resection or liver transplantation). Second-line treatments after sorafenib included BSC, regorafenib or treatments with curative intent as available after SIRT ( and ). The distribution between second-line treatments in each case was informed by data from the SARAH RCT, with an adjustment for use of post-SIRT lenvatinib (which received marketing authorization after treatment assignment in SARAH was complete) based on the assumption of 5% uptake.

Figure 2. Treatment algorithm following initial treatment with selective internal radiation therapy. Abbreviations. BSC, best supportive care; SIRT, selective internal radiation therapy.

Figure 3. Treatment algorithm following initial treatment with sorafenib. Abbreviation. BSC, best supportive care.

Following SIRT (or technical issues arising during SIRT work-up), 42.5% of patients were assumed to receive BSC; 4.6% were assumed to undergo treatment with curative intent based on data from SARAH and the remaining 52.9% of patients (including all patients deemed ineligible for SIRT due to technical contraindications observed during the SIRT work-up) were assumed to receive treatment with lenvatinib (5%) or sorafenib (95%). Of the 4.6% of patients receiving treatments with curative intent after SIRT, 54.3% received tumor ablation, 28.3% received hepatic resection and the remaining 17.4% received a liver transplant, in line with subsequent treatments received by patients in the SIRT arm of the SARAH RCTCitation6. Patients experiencing progression with second-line lenvatinib were subsequently assumed to receive BSC, while patients experiencing progression after second-line sorafenib were assumed to receive either BSC or regorafenib.

Following first-line sorafenib or lenvatinib treatment, 1.4% of patients were assumed to receive treatment with curative intent, again based on subsequent treatments observed in the SARAH trial. Of the 1.4%, 64.3% were assumed to receive tumor ablation and the remaining 35.7% were assumed to receive a liver transplantCitation6.

The per-cycle probability of treatment switching was based on data from pivotal trials of the respective agents (Supplemental Appendix Table 1)Citation14,Citation15. Transition probabilities were derived from the median time on treatment from the respective trials using the EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) where Ti denotes the median time on treatment i, pij represents the proportion of patients on treatment i who subsequently receive treatment j and k represents a constant time unit conversion from the median time on treatment units to model cycle length:

(1)

(1)

Resource use

In patients receiving SIRT with SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres, 8.3% of patients were assumed to require a repeat work-up procedure, while 11.4% of patients would not ultimately receive SIRT due to technical contraindications in line with data from a study into work-up issues associated with SIRT ()Citation16. Of those patients receiving SIRT, 7.1% were assumed to receive a repeat treatment, based on expert opinion in the French setting. The expert opinion was in close alignment with the 325-patient ENRY study of SIRT in patients with HCC, in which 93.2% of patients received one SIRT treatment and the majority (141/147 or 95.9%) of whole-liver treatments were performed in a single sessionCitation17.

Incidence of 28 adverse events was assumed to be the same across all four country settings and was captured based on data from the SARAH RCT across five categories: constitutional symptoms, dermatological events, gastrointestinal disorders, liver disorders and laboratory test abnormalities.

Country-specific data

Country-specific data on the annual incidence of primary liver cancer in each country were obtained from the WHO International Agency for Research on Cancer (WHO IARC)Citation18. The annual number of new cases of primary liver cancer was then derived by multiplying by national population sizes as obtained from the Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques, the Istituto Nazionale di Statistica, the Instituto Nacional de Estadística and the Office for National Statistics, in France, Italy, Spain and the UK, respectivelyCitation19–22. As the WHO IARC data pertains to all primary liver cancer, a multiplier of 0.75 was applied to derive the HCC incidence rate by excluding cholangiocarcinomas, hepatoblastomas, sarcomas, poorly-specified carcinomas and other hepatic malignancies in line with data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) registry (Supplemental Appendix Figure 1)Citation23.

The proportions of patients diagnosed in BCLC stages B and C were derived from country-specific sources where available. In France, data were derived from the CHANGH study, which enrolled 1,207 patients across 103 hepato-gastroenterology units in French hospitals in 2008–2009, of which 894 were ultimately included in the analysisCitation24. Across all 894 patients, 5.5% were diagnosed in BCLC stage B and 46.8% in BCLC stage C. These proportions were then applied to an estimate of the number of incident HCC patients in France (Supplemental Appendix Figure 1). In Italy, data from the ITA.LI.CA database were employed based on a 2015 publication by Giannini et al.Citation25. Of 600 patients with HCC included in the analysis, 23.2% were diagnosed at BCLC stage B and 23.0% were diagnosed at BCLC stage CCitation21. Where country-specific data on BCLC stage at diagnosis could not be identified (Spain and the UK), data from 2,261 patients in Europe were obtained from the HCC BRIDGE study, in which 11.2% of patients were diagnosed at BCLC stage B, and 51.2% of patients were diagnosed at BCLC stage CCitation26. In all country settings, it was assumed that one third of patients in BCLC stage C would be eligible for treatment with SIRT (Supplemental Appendix Figure 1).

Cost data in each country setting were collected from relevant national sources and inflated to 2018 local currency values where necessary using the healthcare component of the local inflation indices.

For the French analysis, costs were derived from multiple sources, with hospital-based costs being based on data from the Étude Nationale des Coûts (National Cost Study; ENC), Classification Commune des Actes Médicaux (CCAM), Nomenclature des Actes de Biologie Médicale (NABM) and Nomenclature Générale des Actes Professionnels (NGAP) tariffs. Costs associated with treatments with curative intent were based on a 2017 cost-effectiveness analysis of early detection and curative treatments for HCC in FranceCitation27. Costs of grade 1 and 2 adverse events in France were based primarily on a multi country analysis of adverse event costs in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma, supplemented with an NGAP GP appointment fee where no specific data were available.Citation28 Costs of grade 3 and 4 adverse events were based on a combination of the ENC data and data collected during the SARAH trial.

In the Italian setting, two recently-published studies of locoregional therapies for HCC in Italy were used to inform the cost collection exercise, and unit costs were cross-checked against health economic studies of metastatic melanoma in ItalyCitation29–32 published by Vouk et al.Citation31 and Wehler et al.Citation32 in 2016 and 2018, respectively. Drug costs in the Italian setting were taken from the Gazzetta Ufficiale either at the time of the approval or the most recent ex-factory price update for sorafenib, lenvatinib and regorafenibCitation33–35. Grade 1 and 2 adverse events in Italy were costed based on the assumption of a single GP interaction for each event, while grade 3 and 4 events were costed based on a combination of DRGs and data from the studies of adverse events in patients receiving treatment for metastatic melanomaCitation31.

In Spain, drug costs were taken from the Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios, while costs of nurse interactions, imaging procedures, clinical examinations and treatments with curative intent were based on tariffs for the Basque Country published by OsakidetzaCitation36. The cost of death was based on a 2014 study of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer by Pericay et al.Citation37assuming 20 days of hospital-based palliative care in 65% of patients.

In the UK, drug costs were sourced from the British National Formulary, while costs of interactions with nurses, general practitioners and podiatry services were based on data from the Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) Unit Costs of Health & Social Care 2018 reportCitation38,Citation39. All UK hospital-based treatments and diagnostics were calculated based on healthcare resource group (HRG)-coded data from the 2017–2018 National Schedule of Reference CostsCitation40. The cost of death in the UK was based on the social care component of care costs in the last twelve months of life from the PSSRU reportCitation35. In all four country settings, the costs associated with SIRT with SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres were based on diagnosis-related groups (DRGs), or HRGs in the case of the UK analysis.

Sensitivity analysis

A series of one-way sensitivity analyses were conducted in which the sensitivity of model outcomes to changes in individual model parameters was investigated. Sensitivity analyses conducted included eliminating transitions to treatments with curative intent; removing costs of all adverse events, then grade 1/2 and grade 3/4 events separately; switching to data from the SARAH trial to inform the proportion of patients deemed ineligible for SIRT after the work-up; and switching to data from the SIRveNIB and SARAH RCTs (as opposed to expert opinion) to inform the proportion of patients in whom repeat SIRT treatments were performed. In the SARAH RCT, 18.8% of patients were not ultimately eligible for SIRT due to a combination of high (>20%) lung shunt fraction (LSF), gastrointestinal uptake of 99mTc macroaggregated albumin during work-up, and/or advanced disease. In SIRveNIB and SARAH, 2.3% and 37% of patients respectively received at least one repeat treatment, compared with the 7.1% assumed in the present base case on the basis of expert opinion in France. Finally, two analyses were conducted in which patients who went on to receive any systemic therapy after SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres were assumed to receive lenvatinib in 10 and 20% of cases (with the remainder receiving sorafenib), compared to 5% in the base case analysis.

Results

Overall survival and progression-free survival analysis

AIC and BIC criteria identified the generalized gamma models to be the best fit to the SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres Kaplan-Meier data from the SARAH trial for both OS and PFS, while lognormal models were the best fit to the sorafenib OS and PFS data (Supplemental Appendix Table 2).

Base case analyses

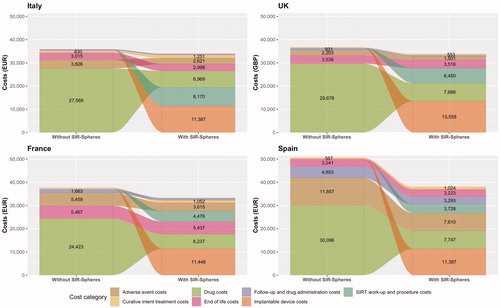

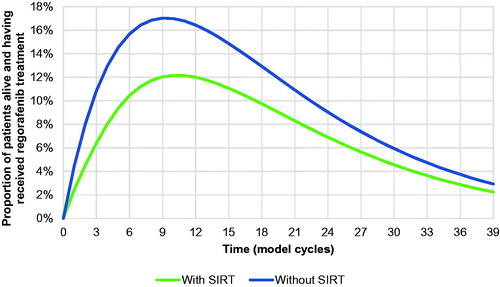

Relative to the scenario without SIRT, the cost analysis projected savings with SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres in all four country settings ( and ). Cost savings in the scenario with SIRT were 7.7% in the UK, 11.7% in France, 5.4% in Italy and 26.5% in Spain, relative to the scenario without SIRT. Initial treatment with SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres was also projected to result in an increase in the proportion of patients ultimately eligible to undergo treatments with curative intent from 1.4% in the scenario without SIRT to 4.6% in the scenario with SIRT (), corresponding to 71 additional patients treated with curative intent across the four countries. Of the patients not receiving treatments with curative intent, fewer patients in the SIRT arm also ultimately received regorafenib, which was modeled as the “last line” of therapy before BSC (). The model projected that mean life expectancy would be 1.176 years with SIR-Spheres versus 1.168 years with sorafenib, representing a negligible increase of 0.009 years.

Figure 4. Cost analyses of SIRT with SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres versus tyrosine kinase inhibitors in France, Italy, Spain and the UK showing average costs per patient eligible for treatment with SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres. Abbreviations. EUR, 2018 Euros; GBP, 2018 pounds sterling; SIRT, selective internal radiation therapy; UK, United Kingdom.

Figure 5. Proportion of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma ultimately receiving treatments with curative intent after SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres and tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

Figure 6. Proportions of patients alive and having received regorafenib treatment over the duration of the analysis illustrating the effect of more patients receiving curative intent, and regorafenib coming later in the treatment algorithm, with the use of SIRT. Abbreviation. SIRT, selective internal radiation therapy.

Table 1. Country-level results of the base case cost analyses of SIRT with SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres versus tyrosine kinase inhibitors in France, Italy, Spain and the UK.

Across all four country settings, the largest modeled category of expenditure was drug costs in the scenario without SIRT, and the cost of the SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres in the scenario with SIRT. The contributions of the other modeled cost categories varied between countries, but drug costs and SIRT work-up and procedure costs were substantial contributors to costs in the “with SIRT” arm in all country settings. Regardless of the differences between the cost categorizations, the overall costs per patient were closely aligned across the UK, French and Italian settings, with only the Spanish analysis reporting higher costs overall, driven predominantly by the higher costs associated with treating grade 3 and 4 adverse events.

Sensitivity analyses

One-way sensitivity analyses showed the model to be relatively insensitive to changes in the parameters investigated (). One notable exception was the exclusion of adverse event costs in the Spanish setting, which reduced the cost in the scenario without SIRT by 25% and the cost in the scenario with SIRT by 22%. Further analysis showed that the change in cost was driven predominantly by the exclusion of the grade 3 and 4 events. Changes in costs arising from omitting treatments with curative intent from the analysis were mixed; in the analyses, patients who would otherwise have undergone radiofrequency ablation, resection or liver transplant were instead treated with sorafenib and, as such, the analysis is reflective of the relative costs of treating with curative intent versus sorafenib treatment. The analysis in which 37% of patients received subsequent SIRT treatments showed that the scenario with SIRT would still be cost saving in the French and Spanish settings, but would be fractionally more expensive than the “without SIRT” in the Italian and UK settings, where costs would be anticipated to be 3.5% (EUR 1257) and 2.7% (GBP 973) higher per treated patient, respectively.

Table 2. One-way sensitivity analysis results.

Discussion

The analysis showed SIRT with SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres to be cost saving relative to the TKIs sorafenib or lenvatinib in the treatment of unresectable HCC across four European countries in patients with HCC in BCLC stages B and C. Treatment with SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres was also projected to increase the proportion of patients eligible for treatments with curative intent.

The present analysis has a number of strengths; it represents a comprehensive effort to model realistic progressions of patients with BCLC B or C HCC through multiple treatment lines, and the analyses were based on an extensive, multi-country cost collection exercise, capturing drug and administration costs; follow-up costs, including nurse visits, clinical exams, CT scans, podiatry services; laboratory test costs; 28 adverse events; costs of SIRT work-up and procedure, including dosimetry and technical issues and repeat treatments; cost of SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres; and palliative care and end-of-life costs. Furthermore, certain aspects of the base case analysis were conservative with respect to the scenario with SIRT, notably using higher rates of retreatment with SIRT (thereby incurring higher costs) than those reported in SIRveNIB and using lower rates of drop-out from SIRT work-up to treatment than those reported in SARAH (thereby resulting in more patients ultimately receiving SIRT).

The modeling of progression through subsequent treatment lines used a novel approach in which transitions between the PFS, PPS and death states were captured using a conventional partitioned survival AUC cohort model, while a nested Markov process drove transitions between subsequent treatments based on transition probabilities derived from point estimates of the median time on treatment with sorafenib, lenvatinib and regorafenib. Developing realistic models of treatment switching can be particularly challenging in oncology where treatments may be poorly tolerated or only efficacious over relatively short time periods. Modeling survival in populations in which substantial proportions of control arm patients have switched treatment can be particularly challenging in intent-to-treat (ITT)-based analyses, potentially resulting in a significant underestimation of efficacy. Techniques such as rank-preserving structural failure time models, iterative parameter estimation and inverse probability of censoring weights are well-established methods of correcting for these effects, but all rely on access to patient-level data and none directly address the effects of switching onto non-investigational treatments or of patients receiving multiple lines of treatmentCitation41–43.

Given the objective of capturing the costs of subsequent treatment with lenvatinib, regorafenib and treatments with curative intent in the present analysis, a patient-level data-based modeling approach employing survival correction was not feasible, and the nested Markov model employed represents a pragmatic solution for modeling the use of newer agents within partitioned survival models based on data from trials predating the use of the newer treatment(s). Transitions between the PFS, PPS and death states were still based on data from the SARAH trial and OS may therefore have been underestimated, but the approach nevertheless appears to provide a reasonable estimate of the proportion of patients receiving second- and third-line therapies over time. The use of fixed per-cycle transition probabilities to capture treatment discontinuation in the present analysis could be the subject of future improvements to the methodology, in which time-dependent probabilities could be modeled based on, for instance, conditional Poisson, negative binomial or other discrete probability distributions.

The analysis also had a number of limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. Challenges arose in accurately costing adverse events across the four country settings, primarily due a lack of data on the cost of adverse events specifically in patients with HCC. For instance, the French and Italian analyses relied on adverse event cost data from studies in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma and melanoma, respectively. While the costs of treating the same treatment-emergent adverse events would not be expected to materially differ between types of cancer, the provenance of the adverse event cost data should be taken into account, especially given the incremental cost differences that were driven by different adverse event costs across the four country settings.

When interpreting any cost analysis, it is worth considering the broader implications. By definition, budget impact analyses focus exclusively on financial flows, without considering differences between the scenarios in terms of effectiveness. In the present analysis, the SIRT scenario was cost saving across all four country settings. In the context of cost-effectiveness, this would restrict analysis outcomes to the two lower quadrants of the cost-effectiveness plane and questions on the relative effectiveness of the combined scenarios are therefore reduced to whether the scenario with SIRT would result in equivalent or better outcomes or whether it would worsen patient outcomes. The SARAH trial was designed to establish whether SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres improved OS relative to sorafenib, specifically being 80% powered to detect a four-month increase in OS with SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres versus sorafenib with a bilateral alpha risk of 5%Citation44. The trial may not therefore have been sufficiently powered to detect differences in the trial’s secondary endpoints and the interpretation of differences in secondary endpoints can therefore be challenging. Nevertheless, the SARAH trial reported that SIRT with SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres improved objective response rates and quality of life and increased the proportion of patients subsequently receiving potentially curative therapy, suggesting that SIRT with SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres may therefore dominate sorafenib in a cost-effectiveness analysis based on the SARAH data.

A final potential limitation of the analysis is the speed at which the HCC treatment landscape is evolving. Results from the IMbrave150 study have recently been presented, showing that combination therapy with programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitor atezolizumab and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitor bevacizumab significantly improves OS and PFS in patients with unresectable HCC relative to sorafenibCitation45. The combination of atezolizumab and bevacizumab is not yet approved or reimbursed for the treatment of HCC in any of the countries evaluated in the present analysis, but its potential future approval and uptake should be considered. Cabozantinib, a kinase inhibitor, has also recently been approved for the treatment of HCC in patients who have already received sorafenib by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agencies (EMA)Citation46,Citation47. The cabozantinib approvals were based on the CELESTIAL trial, which showed significantly longer OS and PFS than placebo in this patient groupCitation8. However, despite the EMA approval, the reimbursement status for cabozantinib in the treatment of HCC in Europe is heterogeneous, with the marketing authorization holder (Ipsen Pharmav) not yet having provided evidence submissions to NICE in the UK, AIFA in Italy, or the Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo in Spain. As with atezolizumab and bevacizumab, the cost implications of the future addition of cabozantinib to the second-line HCC armamentarium should therefore also be considered.

Conclusion

The SARAH RCT demonstrated that, relative to sorafenib, SIRT with SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres results in improved objective response rates, a higher proportion of patients ultimately undergoing treatments with curative intent and improvements in quality of life according to the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire. In addition to these benefits, the present analysis demonstrated that SIRT with SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres would result in cost savings relative to systemic treatment with TKIs in eligible patients across four different country settings in Europe. SIRT was projected to be cost saving even with the analysis capturing the substantial costs of curative treatments in a higher proportion of patients with SIRT than with TKIs. SIRT with SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres therefore represents both an efficacious and financially prudent treatment option in patients with unresectable HCC.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Development of the cost model, execution of the cost analyses and preparation of the manuscript were funded by consultancy fees paid from Sirtex Medical United Kingdom Ltd. to Covalence Research Ltd.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

RFP is a director and shareholder of Covalence Research Ltd, which received consultancy fees from Sirtex Medical United Kingdom Ltd., a subsidiary of Sirtex Medical Ltd. (the manufacturer of SIR-Spheres Y-90 resin microspheres), to develop the cost model, conduct the analysis and prepare the manuscript. SS is a director and full-time employee of Sirtex Medical United Kingdom Ltd. VKB, FC and LG are full-time employees of Sirtex Medical United Kingdom Ltd.

JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

FC, SS and VKB conceived of the analysis. RFP developed the cost model. FC, LG, RFP, SS and VKB contributed to country-specific data collection exercises. RFP prepared the first draft of the manuscript. FC, LG, SS and VKB proof-read and critically reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content and accuracy. RFP revised the manuscript and formatted the final manuscript for journal submission.

Previous presentations

A French analysis based on an early version of the cost model (excluding the curative treatment options) was presented at ASHEcon 2019, June 23–26, Washington DC, USA.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (40 KB)Acknowledgements

No assistance in the preparation of this article is to be declared.

Notes

Notes

i Leverkusen, Germany.

ii Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

iii Sirtex, Sydney, Australia.

iv Redmond, WA.

v Paris, France.

References

- World Health Organization. Global Cancer Observatory (GCO). [cited 2019 Aug 16]. Available from http://gco.iarc.fr

- Balogh J, Victor D 3rd, Asham EH, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: a review. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 2016;3:41–53.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Guidelines Version 3.2019: Hepatobiliary cancers, Accessed 2019 Aug 16. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/hepatobiliary.pdf.

- Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(4):378–390.

- Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10126):1163–1173.

- Vilgrain V, Pereira H, Assenat E, et al. Efficacy and safety of selective internal radiotherapy with yttrium-90 resin microspheres compared with sorafenib in locally advanced and inoperable hepatocellular carcinoma (SARAH): an open-label randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(12):1624–1636.

- Chow PKH, Gandhi M, Tan SB, et al. SIRveNIB: selective internal radiation therapy versus sorafenib in Asia-Pacific patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(19):1913–1921.

- Abou-Alfa GK, Meyer T, Cheng AL, et al. Cabozantinib in patients with advanced and progressing hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(1):54–63.

- Akaike H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans Automat Contr. 1974;19(6):716–723.

- Schwarz GE. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann Statist. 1978;6(2):461–464.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Assessing resource impact process manual: technology appraisals and highly specialised technologies. London, UK. 2017. [cited 2020 Jan 23]. Available from https://www.nice.org.uk/Media/Default/About/what-we-do/Into-practice/assessing-resource-impact-process-manual-ta-hst.pdf

- Ghabri S, Autin E, Poullié AI, et al. The French National Authority for Health (HAS) guidelines for conducting Budget Impact Analyses (BIA). Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36(4):407–417.

- Angelis A, Lange A, Kanavos P. Using health technology assessment to assess the value of new medicines: results of a systematic review and expert consultation across eight European countries. Eur J Health Econ. 2018;19(1):123–152.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Lenvatinib for advanced, unresectable, untreated hepatocellular carcinoma [ID1089] appraisal consultation document. [cited 2019 Sep 5]. Available from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/indevelopment/gid-ta10150/documents.

- Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, et al. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10064):56–66.

- Sancho L, Rodriguez-Fraile M, Bilbao JI, et al. Is a technetium-99m macroaggregated albumin scan essential in the workup for selective internal radiation therapy with yttrium-90? An analysis of 532 patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2017;28(11):1536–1542.

- Sangro B, Carpanese L, Cianni R, et al. Survival after yttrium-90 resin microsphere radioembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma across Barcelona clinic liver cancer stages: a European evaluation. Hepatology. 2011;54(3):868–878.

- Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, et al. International Agency for Research on Cancer. France. 2018. [cited 2019 Sep 5]. Available from https://gco.iarc.fr/today

- Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques. Démographie – Population au début du mois – France (inclus Mayotte à partir de 2014). Paris, France. 2019. [cited 2019 Sep 5]. Available from https://www.insee.fr/en/statistiques/serie/001641607

- Istituto Nazionale di Statistica. Bilancio demografico mensile: Periodo gennaio-marzo 2019. Rome, Italy. 2019. [cited 2019 Sep 5]. Available from http://demo.istat.it/pop2019/index_e.html

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Demografía y población: Población residente en España. Madrid, Spain. 2019. [cited 2019 Sep 5]. Available from http://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736176951&menu=ultiDatos&idp=1254735572981

- Office for National Statistics. Population estimates time series dataset (pop): England population mid-year estimate. [cited 2019 Sep 5]. Available from https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/timeseries/enpop/pop

- Altekruse SF, Devesa SS, Dickie LA, et al. Histological classification of liver and intrahepatic bile duct cancers in SEER registries. J Registry Manag. 2011;38(4):201–205.

- Costentin CE, Mourad A, Lahmek P, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma is diagnosed at a later stage in alcoholic patients: results of a prospective, nationwide study: delayed diagnosis of alcohol-related HCC. Cancer. 2018;124(9):1964–1972.

- Giannini EG, Farinati F, Ciccarese F, et al. Prognosis of untreated hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2015;61(1):184–190.

- Park JW, Chen M, Colombo M, et al. Global patterns of hepatocellular carcinoma management from diagnosis to death: the BRIDGE Study. Liver Int. 2015;35(9):2155–2166.

- Cadier B, Bulsei J, Nahon P, et al. Early detection and curative treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: a cost-effectiveness analysis in France and in the United States. Hepatology. 2017;65(4):1237–1248.

- Mickisch G, Gore M, Escudier B, et al. Costs of managing adverse events in the treatment of first-line metastatic renal cell carcinoma: bevacizumab in combination with interferon-alpha2a compared with sunitinib. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(1):80–86.

- Rognoni C, Ciani O, Sommariva S, et al. Trans-arterial radioembolization for intermediate-advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a budget impact analysis. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):715.

- Rognoni C, Ciani O, Sommariva S, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of treatments involving radioembolization in intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. J Comp Eff Res. 2018;7(3):209–221.

- Vouk K, Benter U, Amonkar MM, Marocco A, et al. Cost and economic burden of adverse events associated with metastatic melanoma treatments in five countries. J Med Econ. 2016;19(9):900–912.

- Wehler E, Zhao Z, Pinar Bilir S, et al. Economic burden of toxicities associated with treating metastatic melanoma in eight countries. Eur J Health Econ. 2017;18(1):49–58.

- Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana. Rinegoziazione del medicinale per uso umano «Nexavar» ai sensi dell’art. 8, comma 10, della legge 24 dicembre 1993, n. 537. (Determina n. DG 411/2018). [cited 2019 Sep 5]. Available from https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2018/04/05/18A02265/sgLast

- Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana. Regime di rimborsabilità e prezzo di vendita del medicinale per uso umano «Lenvima». (Determina n. 718/2016). [cited 2019 Sep 5]. Available from https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/gu/2016/06/10/134/sg/pdf

- Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana. Regime di rimborsabilita’ e prezzo, a seguito di nuove indicazioni terapeutiche, del medicinale per uso umano «Stivarga». (Determina n. 1399/2018). [cited 2019 Sep 5]. Available from https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2018/09/25/18A06064/SG.

- Osakidetza. Tarifas para Facturación de Servicios Sanitarios y Docentes de Osakidetza para el Año 2018. [cited 2019 Oct 10]. Available from https://www.osakidetza.euskadi.eus/contenidos/informacion/libro_tarifas/es_libro/adjuntos/TARIFA_2018_CAS.pdf

- Pericay C, Frías C, Abad A, et al. Análisis coste-efectividad de aflibercept en combinación con FOLFIRI en el tratamiento de pacientes con cancer colorrectal metastásico. Farm Hosp. 2014;38(4):317–327.

- NICE British National Formulary. [cited 2019 Aug 16]. Available at http://bnf.nice.org.uk/

- Curtis LA, Burns A. Unit costs of health and social care 2018. Project report. Canterbury, UK: University of Kent; 2018.

- National Health Service England Improvement. Reference costs. [cited 2019 Aug 16]. Available from https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/reference-costs/

- Robins JM, Tsiatis AA. Correcting for non-compliance in randomized trials using rank preserving structural failure time models. Commun Stat Theory Methods. 1991;20(8):2609–2631.

- Branson M, Whitehead J. Estimating a treatment effect in survival studies in which patients switch treatment. Statist Med. 2002; 21(17):2449–2463.

- Robins JM, Finkelstein DM. Correcting for noncompliance and dependent censoring in an AIDS clinical trial with inverse probability of censoring weighted (IPCW) log-rank tests. Biometrics. 2000;56(3):779–788.

- Vilgrain V, Abdel-Rehim M, Sibert A, et al. Radioembolisation with yttrium‒90 microspheres versus sorafenib for treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (SARAH): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15(1):474.

- Cheng A-L, Qin S, Ikeda M, et al. IMbrave150: efficacy and safety results from a ph III study evaluating atezolizumab (atezo) + bevacizumab (bev) vs sorafenib (Sor) as first treatment (tx) for patients (pts) with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Ann Oncol. 2019;30(S9):ix186–ix187.

- Food and Drug Administration. Cabometyx (cabozantinib) supplement approval. Silver Spring, MD, USA: Food and Drug Administration; 2019. [cited 2020 Jan 23]. Available from https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2019/208692Orig1s003ltr.pdf

- European Medicines Agency. Cabometyx-H-C-004163-II-0005: EPAR – Assessment report – variation. Amsterdam, Netherlands; 2018. [cited 2020 Jan 23]. Available from https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/variation-report/cabometyx-h-c-004163-ii-0005-epar-assessment-report-variation_en.pdf