Abstract

Aims: This study estimated the economic and humanistic burden associated with chronic non-communicable diseases (NCCDs) among adults with comorbid major depressive and/or any anxiety disorders (MDD and/or AAD).

Materials and methods: A retrospective analysis was conducted using the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey data (2010–2015). The analytic cohort included adults (≥18 years) with MDD only (C1), AAD only (C2), or both (C3). The presence of either of 6 NCCDs (cardiovascular diseases [CVD], pulmonary disorders [PD], pain, high cholesterol, diabetes, and obesity) were assessed. Study outcomes included healthcare costs, activity limitations, and quality of life. Multivariate regressions were conducted in each of the 3 cohorts to evaluate the association between the presence of NCCDs and outcomes.

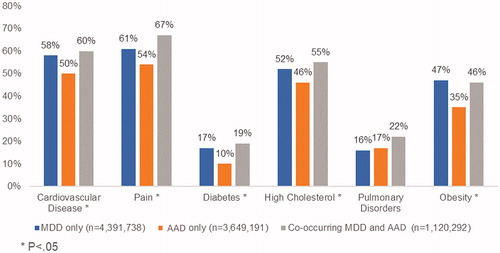

Results: The analytic sample included 9,160,465 patients: C1 (4,391,738), C2 (3,648,436), C3 (1,120,292). Pain (59%) was the most common condition, followed by CVD (55%), high cholesterol (50%), obesity (42%), PD (17%), and diabetes (14%). Mean annual healthcare costs were the greatest for C3 ($14,317), followed by C1 ($10,490) and C2 ($7,906). For C1, CVD was associated with the highest increment in annual costs ($3,966) followed by pain ($3,617). For C2, diabetes was associated with the highest incremental annual costs ($4,281) followed by PD ($2,997). For C3, cost trends were similar to those seen in C2. NCCDs resulted in a significant decrease in physical quality of life across all cohorts. Pain was associated with a significantly higher likelihood of self-reported physical, social, cognitive, and activity limitations compared to those without pain.

Conclusions: 60% of patients with MDD and/or AAD had at least one additional NCCD, which significantly increased the economic and humanistic burden. These findings are important for payers and clinicians in making treatment decisions. These results underscore the need for development of multi-pronged interventions which aim to improve quality of life and reduce activity limitations among patients with mental health disorders and NCCDs.

JEL CLASSIFICATION CODES:

Introduction

In the United States (US), 6.8 million adults are affected by any anxiety disorders (AAD) and 16.1 million adults are affected by major depressive disorder (MDD) annuallyCitation1. Previous studies have reported that AAD and MDD are frequently comorbid in the US, with estimates of 58% to 59% of casesCitation2–4. Patients with MDD have severely impaired quality of life (QOL) compared to population normsCitation5–7, as do patients with AADCitation8,Citation9, but patients with comorbid MDD and AAD have significantly worse QOL outcomes than those with either disorder aloneCitation9,Citation10. The impaired QOL in these patients may be also associated with altered neuropsychological functioningCitation11. These disorders also have a high economic burden in the US, estimated at $210.5 billion for MDD for the year 2010Citation12 and $33.71 billion for anxiety disorders generally (including but not limited to AAD) in 2010Citation13.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report chronic conditions such as obesity, arthritis, depressive disorder, high blood pressure, high blood cholesterol, diabetes, coronary heart disease, and stroke as leading causes of US morbidity and mortalityCitation14. A recent study projected mental health disorders (MHDs) such as MDD and/or AAD, cardiovascular diseases, cancer, diabetes, and chronic respiratory diseases would incur a total loss of $94.9 trillion in the United States from the years 2015 to 2050Citation15. Patients with MDD and/or AAD have a higher likelihood of suffering from non-communicable chronic diseases (NCCDs) such as diabetes, pain, and pulmonary disordersCitation16–19. Comorbidity of MHDs and NCCDs is associated with higher medical expenditure and greater healthcare resource use (HCRU)Citation16,Citation18,Citation20.

Although the burden of mental health conditions such as AAD and MDD among patients with other chronic conditions has been well characterized in the literature, the prevalence and humanistic and economic burden of various NCCDs among patients with MDD and/or AAD have not yet been well establishedCitation21–23. In this study we sought to understand the cost of care and losses in QOL associated among patients with MDD, AAD, or co-occurring MDD and AAD who have multiple comorbid NCCDs. Specifically, this study estimates the HCRU, total costs, productivity losses, health limitations, and QOL impact associated with various NCCDs while controlling for the presence of other NCCDs among adult patients diagnosed with MDD, AAD, or co-occurring MDD and AAD.

Methods

Study design and data source

This was a retrospective cross-sectional database study using pooled Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) data from years 2010 to 2015, which was the latest data cut available at the time the study was conducted. Established in 1996, MEPS is sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and is a nationally representative survey of the US civilian noninstitutionalized population that collects detailed information on health status, health insurance coverage, healthcare utilization and expenditures, and a variety of demographic, clinical, and economic characteristicsCitation17. MEPS employs a complex survey design and uses 3 weighting variables (person, stratum, and primary sampling unit) to yield estimates that are generalizable to a national sample of noninstitutionalized US adultsCitation24. This study used the Household Component of MEPS, which collects data from each individual in a selected household through 5 rounds of personal interviews over 30 months to produce 2 full calendar years of annual dataCitation25, which are supplemented with data from the individuals’ medical and insurance providers and employers. MEPS contains publicly available de-identified data, so no review by an Institutional Review Board was deemed necessary.

Study population

Patients were identified from the medical conditions’ files using the first 3 digits of the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) and Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) diagnosis codes for MDD (ICD-9-CM: 311) and/or AAD (CCS: 651). Patients were required to have either of the 2 codes present for each survey round in order to be defined as having MDD and/or AAD. To be eligible for inclusion for a given year, patients had to be aged 19 years or older as of December 31st of that year and had to be part of eligible households. Additionally, they were also required to be in-scope for data collection in all rounds of the survey to ensure that our final sample included only those patients who were present during the survey in each round. A small percentage of people surveyed for MEPS may not be in-scope for certain times of the year. These persons include those who had time periods during the year when they lived in an institutional setting (e.g. hospital, nursing home, or prison), were in the military, lived outside the country, were born (or adopted) into households from which the MEPS sample was selected, or died during the yearCitation26. Patients with any history of cancer (ICD-9-CM: 140-239 and/or CCS: 11-47) were excluded, as were patients with any of the following mental health conditions in any survey round during the respective year: adjustment disorder (CCS: 650); personality disorders (CCS: 658); schizophrenia and psychotic disorders (CCS: 659); substance-related disorders (CCS: 660, 661); delirium, dementia, and amnestic disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease (CCS: 653); bipolar disorder (ICD-9-CM: 296.xx); or Parkinson’s disease (CCS: 079).

Variables

Independent variables

The primary independent variables of interest were the presence or absence of 6 NCCDs: cardiovascular disease (CVD), pain, diabetes, high cholesterol, pulmonary disorders, and obesity (). Except for obesity, these NCCDs are considered “priority conditions” by the AHRQ due to their prevalence, expense, or relevance to policyCitation27. Obesity was included in this analysis per clinical input from experts.

Table 1. List of NCCDs assessed.

Outcome variables

Two sets of outcomes were analyzed: economic and humanistic. Economic outcome variables included measures of direct burden (annual number of inpatient, outpatient facility, emergency department [ED], and office-based visits, as well as the average inpatient length of stay; and annual medical costs reported in 2018 US dollars) and indirect burden (productivity loss, defined as number of work days missed in the respective year). Humanistic outcomes were measured in terms of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and health limitations. The HRQOL of MEPS participants was assessed using the 2 summary scores calculated from patients’ responses to the 12-Item Short Form Health Survey Version 2 (SF-12v2) questionnaire – the physical component summary (PCS) score and the mental component summary (MCS) scoreCitation28. Higher scores on PCS and MCS indicated a better QOL. Health limitations were assessed based on patients’ self-reported limitations (yes/no) in the following domains: functional limitations, limitations in activities of daily living (ADLs), social/recreational limitations, and cognitive limitations.

Covariates

Data on key sociodemographic and clinical covariates were obtained from the MEPS full-year consolidated data files for each patient. Individual sociodemographic covariates included age, sex, census region, insurance status, race, employment status, family income, and marital status. The clinical covariates included were depression and anxiety severity, which were measured using the patient's score on the Kessler 6 (K-6) index (range 0–24)Citation29. The K-6 index has shown to be an effective indicator of distress severityCitation30. Depression severity was estimated as sum of scores on questions 2, 3, 4 and 6 and anxiety severity was the sum of items 1 and 5. Previous factor analysis supports this 2-domain underlying structure of the scaleCitation31.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics for each analytic cohort (MDD only, AAD only, co-occurring MAD and AAD) were described using median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables and frequency and percentages for categorical variables. Bivariate comparisons between cohorts were made using Chi-square tests for categorical variables and Kruskal Wallis test for continuous, non-normal variables (age, MDD severity, and AAD severity). For each analysis, data from only complete records were included. Patients with missing data on the outcome or independent variable or any of the covariates used in the analyses were excluded for the respective analysis.

The prevalence of NCCDs was calculated as the proportion of patients experiencing the NCCD in each cohort and Chi-square tests were used to compare the prevalence of NCCDs between the 3 analytic cohorts. The proportion of patients experiencing multiple (≥2) NCCDs in each cohort was also reported.

Separate multivariate generalized linear models (GLMs) were used for each analytic cohort to estimate the incremental difference in each outcome associated with the presence of each respective NCCD after adjusting for the above stated covariates and presence of other NCCDs. For ED, inpatient, and outpatient visits, zero-inflated Poisson GLMs with logarithmic link were used to account for the high probability of not experiencing the outcome. For office-based visits and productivity losses (i.e. number of work days missed), we used GLMs with a Poisson distribution and logarithmic link. Annual medical costs were estimated using GLMs with a gamma distribution and logarithmic link.

Multivariate logistic regression models were used to estimate the odds ratios of reporting the presence of health limitations in each domain associated with each NCCD. Multivariate linear regression models were used to estimate the increment/decrement in SF-12v2 PCS and MCS scores associated with each NCCD.

All analyses accounted for MEPS’ complex survey design by using AHRQ-recommended methods for weighting and samplingCitation26. Specifically, participants’ annual weight estimates were used to determine the number of US individuals represented by the patients sampled. Also, analytic sampling weights were adjusted by dividing by the number of years of pooled data. The sum of these adjusted weights represented the average annual population size for the study period. Adjusting by these weights allowed each result to be interpreted at an “average annual” basis rather than the entire pooled period. The primary sampling unit and stratification information for each participant was also incorporated to account for variance around point estimatesCitation32,Citation33. All analyses were performed using survey procedures in SAS 9.4 and Stata 14.

Results

Patient selection

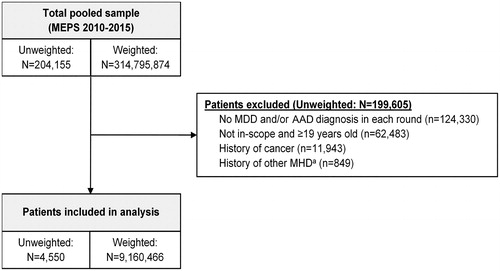

A total of 4,550 survey respondents from 2010 to 2015 were included in the final analytic sample, which represented 9,160,466 persons (). The weighted (unweighted) sample size for each analytic cohort was 4,391,738 (2,220) patients for MDD only, 3,648,436 (1,743) for AAD only, and 1,120,292 (587) for co-occurring MDD and AAD ().

Figure 1. Patient flow chart. Abbreviations: AAD, any anxiety disorder; MDD, major depression; MHD, mental health disorder; MEPS, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. aBipolar disorder, adjustment disorder, personality disorder, schizophrenia and psychotic disorders, substance-related disorders, delirium, dementia, amnestic disorders (including Alzheimer’s disease), and Parkinson’s disease.

Table 2. Weighted socio-demographic characteristics of patients with MDD only, AAD only, and co-occurring MDD and AAD.

Patient/sample characteristics

Patients with co-occurring MDD and AAD were more likely to be non-white, unemployed, and have a low household income, but other demographic characteristics were similar across the 3 analytic cohorts (). Patients with co-occurring MDD and AAD had higher MDD severity (median: 4.9, IQR: 1.6–8.9) and AAD severity (median: 3.4, IQR: 2.0–4.7) as measured using the K-6 index compared to those with MDD only (median: 2.9, IQR: 0.3–6.9) or AAD only (median: 2.1, IQR: 0.9–3.6).

Outcomes

Prevalence of NCCDs in patients with MDD and/or AAD

The prevalence of NCCDs was significantly higher among patients with co-occurring MDD and AAD compared to those with either condition only (). Across all cohorts, pain (59%) was the most common condition, followed by CVD (55%), high cholesterol (50%), obesity (42%), pulmonary disorders (17%), and diabetes (14%). Multiple NCCDs (≥ 2) were present in 72%, 61%, and 74% of the MDD only, AAD only, and co-occurring MDD and AAD cohorts, respectively.

Economic burden of NCCDs in patients with MDD and/or AAD

Presence of pain was associated with a significantly (p ≤.05) higher mean number of annual per patient ED visits, outpatient facility visits, and office-based visits among all 3 analytic cohorts (). Pain was also associated with significantly (p ≤.05) greater productivity losses among all 3 cohorts as measured by the mean number of work days missed in the respective year (). CVD was associated with a higher mean number of annual per patient inpatient visits and average length of stay in the MDD only and AAD only cohorts ().

Table 3. Adjusted mean (SE) difference in HCRU for present vs absent NCCDs among patients with MDD only, AAD only, or co-occurring MDD and AAD.

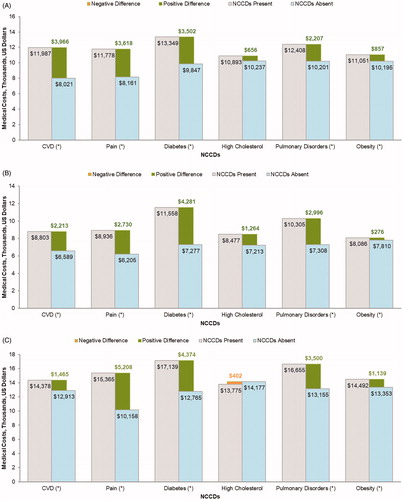

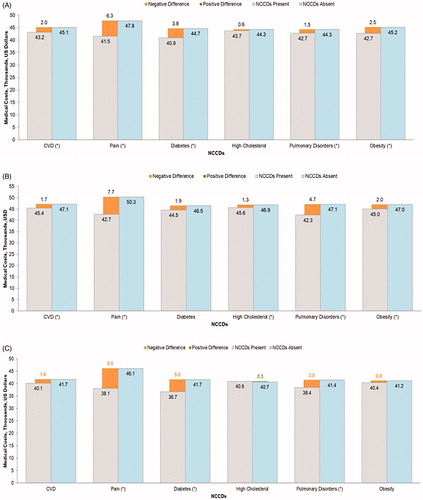

The incremental difference in annual medical costs associated with presence of NCCDs is depicted in . Mean annual healthcare costs, irrespective of the presence/absence of NCCDs, were the greatest for patients with co-occurring MDD and AAD ($14,317), followed by MDD only ($10,490) and AAD only ($7,906). CVD was associated with the highest increment in annual costs ($3,966), followed by pain ($3,618), diabetes ($3,502), and pulmonary disorders ($2,207) in the MDD only cohort. Diabetes was associated with the highest incremental annual costs ($4,281), followed by pulmonary disorders ($2,996), pain ($2,730), and CVD ($2,213) in the AAD only cohort. Among patients with co-occurring MDD and AAD, pain was associated with the highest increment in annual medical costs ($5,208) followed by diabetes ($4,374), pulmonary disorders ($3,500), CVD ($1,465), and obesity ($1,139).

Figure 3. Adjusted per patient per year total medical cost associated with each NCCD among patients with (A) MDD only, (B) AAD only, and (C) co-occurring MDD and AAD. Abbreviations: AAD, any anxiety disorder; CVD, cardiovascular disease; MDD, major depressive disorder; NCCD, noncommunicable chronic disease. *p < .05.

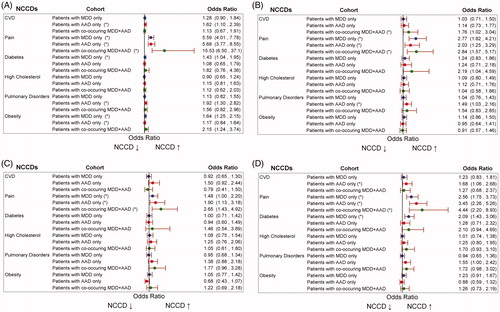

Pain was associated with significantly higher odds of reporting health limitations in all 3 cohorts, with the most impact on self-reported functional limitations and least impact on self-reported cognitive limitations (). NCCDs associated with higher odds of reporting social limitations included pulmonary disorders in the AAD only cohort and CVD in the co-occurring MDD and AAD cohort. NCCDs associated with higher odds of reporting limitations in ADLs included CVD in the AAD only cohort and diabetes in the MDD only cohort.

Figure 4. Adjusted odds ratios (95% CIs) associated with each NCCD for (A) functional limitations, (B) social limitations, (C) cognitive limitations, and (D) limitations in ADLs among patients with MDD only, AAD only, and co-occurring MDD and AAD. Abbreviations: AAD, any anxiety disorder; ADLs, activities of daily living; CVD, cardiovascular disease; MDD, major depressive disorder; NCCD, noncommunicable chronic disease. *p < .05

Pain was associated with the highest decrement in SF-12v2 PCS scores in all 3 cohorts (). None of the NCCDs had any impact on MCS scores (regression results not shown). However, the mean MCS score for the study population was 42, which indicates worse mental health status compared with the US norm population.

Figure 5. Adjusted mean SF-12v2 PCS scores associated with each NCCD among patients with (A) MDD only, (B) AAD only, and (C) co-occurring MDD and AAD. Abbreviations: CVD, cardiovascular disease; AAD, anxiety disorder; MDD, major depressive disorder; NCCD, noncommunicable chronic disease; PCS, physical component summary; SF-12v2, 12-Item Short Form Health Survey Version 2. *p < .05.

Discussion

This was one of the first studies to assess the burden of NCCDs among patients with MHDs using a comprehensive set of economic and humanistic outcomes. The results from this analysis are generalizable to a sample of noninstitutionalized US adults and are crucial for clinicians, health policy makers, and payers in driving treatment decisions and allocating resources to patients with multi-morbidity. These results showed that over 60% of patients with MDD and/or AAD have 2 or more comorbid NCCDs, with pain being the most prevalent NCCD. Patients with co-occurring MDD and AAD have greater depression and anxiety severity compared to patients with MDD only or AAD only. The presence of NCCDs, especially pain and CVD, increases the economic and humanistic burden and leads to worse QOL among patients with MHDs.

The majority of literature regarding MHDs and NCCDs focuses on the burden of MHDs among patients with NCCDs. In contrast, this study provides nationally representative estimates of the prevalence and burden of NCCDs among patients with MHDs. Our results show that patients with MDD and AAD have high prevalence of NCCDs, which aligns with previous literature showing that patients with MHD have higher risks of obesityCitation34, CVDCitation35, diabetesCitation36, and pulmonary diseaseCitation37. The prevalence of pain, CVD, and hyperlipidemia in our population exceeded that of the overall adult population of the United States by nearly 30%Citation38. MHDs have been linked to NCCDs through clinical mechanisms such as immune and inflammatory pathways, neighborhood effects due to income inequality, stigmatization of MHD patients that may lead to delayed or inappropriate treatment of NCCDs, and adverse effects of pharmacotherapy for MHDs which can lead to metabolic syndromeCitation39. Previous studies have also shown that patients with MHD have higher prevalence of modifiable risk factors for NCCDs such as smoking, physical inactivity, being overweight, or poor adherence to medicationCitation40–42. Thus, our findings highlight the importance of preventive measures such as patient trainingCitation39 and improving patients’ health literacy so that they can make healthier lifestyle changes that mitigate the risk of NCCDs and thereby reduce the associated economic and humanistic burden among patients with MHDs.

Our results also show that NCCDs have higher economic costs and HCRU and need better management among patients with MHD. However, patients with MHDs tend to experience barriers in care due to under-resourcing of mental health fragmented care and lack of integration between psychiatry and general medicineCitation43 or stigma from providersCitation44. Systemic changes such as co-location of services, having staff from one service visit another service on a regular basis, and/or appointing case managers to liaise between services and coordinate the patient’s overall careCitation45 could ensure better care of patients with MHDs and reduce their financial burden. In cases where MHD treatment is provided in non-specialist settings it is recommended to complement the services with liaison psychiatrists and health psychologists who have experience in the integration of NCCDs with MHDsCitation46. Evidence from randomized controlled trials of collaborative care has also suggested that integration of MHD care can improve health outcomes in NCCDs such as CVD and diabetesCitation47,Citation48.

While the impact of MHD on QOL among patients with NCCDs has been studiedCitation21,Citation22,Citation49, ours is one of the first studies to quantify the impact of NCCDs on QOL among patients with MHDs. We found that NCCDs did not impact the mental health of these patients, which could be because all patients had existing MHDs. This finding also correlates with previous studies that have shown that the NCCDs included in our study do not influence MCS but do lead to deteriorations in PCSCitation19,Citation50. Our estimates of the impact of NCCDs on PCS show that NCCDs lead to a greater deterioration in PCS among patients with MHDs compared to the general population. Additionally, we find NCCDs increased the limitations in ADLs of patients with MHDs. These results further substantiate the importance of monitoring the physical health of patients with MHDs. These results also underscore the need for development of multi-pronged interventions which aim to improve physical and mental QOL and reduce the limitations in ADLs among patients with MHDs and NCCDs. Future studies must explore factors that impact QOL and ADLs in this patient population.

There are certain limitations to this study which must be acknowledged. First, we employed a cross-sectional design and therefore it is not possible to establish causal inferences between MHDs and healthcare costs. A cross-sectional design also prevents us from establishing temporality and understanding whether the NCCDs were a manifestation of the MHD or vice versa. Despite the absence of causality, these findings highlighting the burden associated with NCCDs in patients with MDD and/or AAD are important for driving clinical practice. Additionally, the study was subject to the limitations of MEPS data, as the survey’s complex sample design may result in a higher variance in estimates than would result from a simple random sample due to clustering, multistage sample selection, and unequal weightingCitation25. Furthermore, MEPS data on psychiatric inpatient utilization may not be representative for patients with MHDs due to underreporting of psychiatric inpatient use by MEPS respondents and/or underrepresentation of individuals with severe MHDs, as people who live in residential care facilities or other institutions (e.g. psychiatric hospitals, nursing homes, jails/prisons) are excluded from the MEPS sampleCitation51. Another limitation of our data is that, although severity of each MHD was controlled for using the K-6 index, the MEPS data did not allow us to control for severity of NCCDs. Our sample of patients was restricted to patients with a medical visit having a diagnosis of MDD and/or AAD. In practice these conditions are vastly underdiagnosed and underreported and the undiagnosed patients may have a greater disease burden due to untreated MHDsCitation52. However, these limitations do not negate the survey’s usefulness as a versatile and comprehensive data source.

Conclusions

The prevalence of NCCDs is high among patients with MDD and/or AAD, and patients with both conditions fare worse than those with 1 condition alone. The presence of NCCDs increases economic burden and productivity losses among patients with MDD only, AAD only, and co-occurring MDD and AAD, compounding these patients’ high baseline costs due to their MHD(s). Our findings emphasize the importance of managing NCCDs in this population to reduce the HCRU and cost burden that these NCCDs place on patients as well as payers. Though many pharmacological and behavioral therapies are available to treat MHDs, we do not know which approaches are best to lower the risk of developing NCCDs among patients with MHDs. Future research needs to focus on developing interventions to prevent and manage NCCDs in patients with MHDs.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Research funding was provided by Pfizer Inc.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

Ruchit Shah, Anuj Shah, and Jennifer Stephens are employees of Pharmerit International, which received research funding from Pfizer Inc. for this study. Elizabeth Pappadopulos, Richard Chambers, and Patricia Schepman are employees of Pfizer Inc. and own Pfizer stock. Eric Armbrecht and Roger S. McIntyre have received consulting fees from Pfizer Inc. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

The study was designed by Eric Armbrecht, Anuj Shah, Patricia Schepman, Ruchit Shah, Elizabeth Pappadopulos, Richard Chambers, Jennifer Stephens, Seema Haider, and Roger McIntyre. The data were analyzed by Ruchit Shah and Anuj Shah. Eric Armbrecht, Anuj Shah, Patricia Schepman, Ruchit Shah, Elizabeth Pappadopulos, Richard Chambers, Jennifer Stephens, Seema Haider, and Roger McIntyre wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Previous presentations

Economic burden associated with non-communicable diseases among adults with depression and anxiety in the United States. Presented at the 2019 ISPOR Annual Meeting, New Orleans, LA, USA, May 18–22, 2019. Poster number: PMH16.

Humanistic burden associated with chronic non-communicable conditions among adults with depression and anxiety in the United States. Presented at the 32nd ECNP Congress, Copenhagen, Denmark, September 7–10, 2019. Poster number: P.797.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Catherine Mirvis of Pharmerit International and Gregory Poorman from Pfizer Inc. for providing medical writing assistance for this manuscript.

References

- Anxiety and Depression Association of America. Facts & statistics [cited 2019 Jun 25]. Available from: https://adaa.org/about-adaa/press-room/facts-statistics

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al.; National Comorbidity Survey Replication. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA. 2003;289:3095–3105.

- Kessler RC, Gruber M, Hettema JM, et al. Co-morbid major depression and generalized anxiety disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey follow-up. Psychol Med. 2008;38:365–374.

- Mittal D, Fortney JC, Pyne JM, et al. Impact of comorbid anxiety disorders on health-related quality of life among patients with major depressive disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:1731–1737.

- IsHak WW, Mirocha J, James D, et al. Quality of life in major depressive disorder before/after multiple steps of treatment and one-year follow-up. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2015;131:51–60.

- Rapaport MH, Clary C, Fayyad R, et al. Quality-of-life impairment in depressive and anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1171–1178.

- Saragoussi D, Christensen MC, Hammer-Helmich L, et al. Long-term follow-up on health-related quality of life in major depressive disorder: a 2-year European cohort study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;14:1339–1350.

- Hoffman DL, Dukes EM, Wittchen HU. Human and economic burden of generalized anxiety disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25:72–90.

- Revicki DA, Travers K, Wyrwich KW, et al. Humanistic and economic burden of generalized anxiety disorder in North America and Europe. J Affect Disord. 2012;140:103–112.

- Zhou Y, Cao Z, Yang M, et al. Comorbid generalized anxiety disorder and its association with quality of life in patients with major depressive disorder. Sci Rep. 2017;7:40511.

- Tempesta D, Mazza M, Serroni N, et al. Neuropsychological functioning in young subjects with generalized anxiety disorder with and without pharmacotherapy. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013;45:236–241.

- Greenberg PE, Fournier AA, Sisitsky T, et al. The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2005 and 2010). J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76:155–162.

- Shirneshan E, Bailey J, Relyea G, et al. Incremental direct medical expenditures associated with anxiety disorders for the U.S. adult population: evidence from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. J Anxiety Disord. 2013;27:720–727.

- Pickens CM, Pierannunzi C, Garvin W, et al. Surveillance for certain health behaviors and conditions among states and selected local areas – Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, United States, 2015. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2018;67:1–90.

- Chen S, Kuhn M, Prettner K, et al. The macroeconomic burden of noncommunicable diseases in the United States: estimates and projections. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0206702.

- Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE. Depression and diabetes: impact of depressive symptoms on adherence, function, and costs. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3278–3285.

- Clarke DM, Currie KC. Depression, anxiety and their relationship with chronic diseases: a review of the epidemiology, risk and treatment evidence. Med J Aust. 2009;190:S54–S60.

- Devane CL, Chiao E, Franklin M, et al. Anxiety disorders in the 21st century: status, challenges, opportunities, and comorbidity with depression. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11:S344–S353.

- Xu W, Collet JP, Shapiro S, et al. Independent effect of depression and anxiety on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations and hospitalizations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:913–920.

- Dalal AA, Shah M, Lunacsek O, et al. Clinical and economic burden of depression/anxiety in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients within a managed care population. COPD. 2011;8:293–299.

- Outcalt SD, Kroenke K, Krebs EE, et al. Chronic pain and comorbid mental health conditions: independent associations of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression with pain, disability, and quality of life. J Behav Med. 2015;38:535–543.

- Uchmanowicz I, Gobbens RJ. The relationship between frailty, anxiety and depression, and health-related quality of life in elderly patients with heart failure. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:1595–1600.

- Wallace K, Zhao X, Misra R, et al. The humanistic and economic burden associated with anxiety and depression among adults with comorbid diabetes and hypertension. J Diabetes Res. 2018;2018:4842520.

- Machlin S, Yu W, Zodet M. Computing standard errors for MEPS estimates. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2005 [cited 2019 Aug 21]. Available from: http://www.meps.ahrq.gov/survey_comp/standard_errors.jsp

- Chowdhury SR, Machlin SR, Gwet KL. Sample designs of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component, 1996–2006 and 2007–2016. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2019.

- Machlin S, Yu W. MEPS sample persons in-scope for part of the year: identification and analytic considerations. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2005.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. MEPS HC-180: 2015 medical conditions. Rockville (MD); 2017 [updated 2017 Aug; cited 2019 Jun 26]. Available from: https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_stats/download_data/pufs/h180/h180doc.shtml#Priority2.5.2.1

- Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller S. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233.

- Prochaska J, Sung H, Max W, et al. Validity study of the K6 scale as a measure of moderate mental distress based on mental health treatment need and utilization. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21:88–97.

- Mitchell CM, Beals J. The utility of the Kessler Screening Scale for Psychological Distress (K6) in two American Indian communities. Psychol Assess. 2011;23:752–761.

- Easton SD, Safadi NS, Wang Y, et al. The Kessler psychological distress scale: translation and validation of an Arabic version. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15:215.

- Shah R, Yang Y. Health and economic burden of obesity in elderly individuals with asthma in the United States. Popul Health Manag. 2015;18:186–191.

- Shah R, Nwankwo C, Kwon Y, et al. Economic and humanistic burden of cervical cancer in the United States: results from a nationally representative survey. J Women’s Health. 2020.

- Keck PE, McElroy SL. Bipolar disorder, obesity, and pharmacotherapy-associated weight gain. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:1426–1435.

- Larson SL, Owens PL, Ford D, et al. Depressive disorder, dysthymia, and risk of stroke: thirteen-year follow-up from the Baltimore epidemiologic catchment area study. Stroke. 2001;32:1979–1983.

- Arroyo C, Hu FB, Ryan LM, et al. Depressive symptoms and risk of type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:129–133.

- Himelhoch S, Lehman A, Kreyenbuhl J, et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among those with serious mental illness. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2317–2319.

- Buttorff C, Ruder T, Bauman M. Multiple chronic conditions in the United States. Santa Monica (CA): Rand; 2017.

- Meyer JM, Nasrallah HA. Medical illness and schizophrenia. Arlington (VA): American Psychiatric Publishing; 2009.

- Keenan TE, Yu A, Cooper LA, et al. Racial patterns of cardiovascular disease risk factors in serious mental illness and the overall U.S. population. Schizophr Res. 2013;150:211–216.

- Petry NM, Barry D, Pietrzak RH, et al. Overweight and obesity are associated with psychiatric disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:288–297.

- Whooley MA, de Jonge P, Vittinghoff E, et al. Depressive symptoms, health behaviors, and risk of cardiovascular events in patients with coronary heart disease. JAMA. 2008;300:2379–2388.

- Druss BG. Improving medical care for persons with serious mental illness: challenges and solutions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:40–44.

- Leucht S, Burkard T, Henderson JH, et al. Physical illness and schizophrenia: a review of the evidence. New York (NY): Cambridge University Press; 2007.

- Vreeland B. Bridging the gap between mental and physical health: a multidisciplinary approach. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:26–33.

- Stein DJ, Benjet C, Gureje O, et al. Integrating mental health with other non-communicable diseases. BMJ. 2019;364:l295.

- O'Neil A, Jacka FN, Quirk SE, et al. A shared framework for the common mental disorders and non-communicable disease: key considerations for disease prevention and control. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:15.

- Patel V, Chatterji S. Integrating mental health in care for noncommunicable diseases: an imperative for person-centered care. Health Affairs. 2015;34:1498–1505.

- Schram MT, Baan CA, Pouwer F. Depression and quality of life in patients with diabetes: a systematic review from the European Depression in Diabetes (EDID) Research Consortium. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2009;5:112–119.

- Rijken M, van Kerkhof M, Dekker J, et al. Comorbidity of chronic diseases: effects of disease pairs on physical and mental functioning. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:45–55.

- Slade EP, Goldman HH, Dixon LB, et al. Assessing the representativeness of Medical Expenditure Panel Survey inpatient utilization data for individuals with psychiatric and nonpsychiatric conditions. Med Care Res Rev. 2015;72:736–755.

- Williams SZ, Chung GS, Muennig PA. Undiagnosed depression: a community diagnosis. SSM Popul Health. 2017;3:633–638.