Abstract

Aim

To compare the health economic efficiency of health care systems across nations, within the area of schizophrenia, using a data envelopment analysis (DEA) approach.

Methods

The DEA was performed using countries as decision-making units, schizophrenia disease investment (cost of disease as a percentage of total health care expenditure) as the input, and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) per patient due to schizophrenia as the output. Data were obtained from the Global Burden of Disease 2017 study, the World Bank Group, and a literature search of the PubMed database.

Results

Data were obtained for 44 countries; of these, 34 had complete data and were included in the DEA. Disease investment (percentage of total health care expenditure) ranged from 1.11 in Switzerland to 6.73 in Thailand. DALYs per patient ranged from 0.621 in Lithuania to 0.651 in Malaysia. According to the DEA, countries with the most efficient schizophrenia health care were Lithuania, Norway, Switzerland and the US (all with efficiency score 1.000). The least efficient countries were Malaysia (0.955), China (0.959) and Thailand (0.965).

Limitations

DEA findings depend on the countries and variables that are included in the dataset.

Conclusions

In this international DEA, despite the difference in schizophrenia disease investment across countries, there was little difference in output as measured by DALYs per patient. Potentially, Lithuania, Norway, Switzerland and the US should be considered ‘benchmark’ countries by policy makers, thereby providing useful information to countries with less efficient systems.

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 20–40% of total health spending is wasted because of inefficiency in the health care sector, amounting to almost US$1.5 trillion per year (2010 global estimate)Citation1. In the context of limited health care budgets, where investment in one disease area will limit investment in other areas, it is important to maximize the benefits obtained from available resourcesCitation2. An understanding of the basic principles of health economics, and how this can impact on clinical decision making, is important for health care professionals to allow them to manage budgets, improve efficiency, and ultimately provide the best possible care to their patientsCitation2,Citation3.

Differences in access to care, economic factors, and risk factor profiles across nations can result in inequalities in health care deliveryCitation4. International comparison of health care services can be used to identify ‘benchmark’ countries with efficient health care systems, which may be able to provide useful information to countries with less efficient systems. ‘Data envelopment analysis’ (DEA) has been widely used to rank health care systems by efficiency, both within countries and on an international scaleCitation5. DEA is a non-parametric technique designed to evaluate the relative efficiencies of a set of homogeneous ‘decision-making units’ (DMUs) (in this case, countries) that may use multiple inputs to produce multiple outputsCitation6,Citation7. The choice of inputs and outputs is critical, since different inputs and outputs will produce different efficiency scores and rankingsCitation6,Citation7. Commonly used inputs are health expenditure, number of physicians, and number of hospital beds; commonly used outputs are life expectancy and infant mortalityCitation5.

DEA can be a useful first step to inform future health care policies. Different countries have different health economics and outcomes research (HEOR) evidence requirements, which may be budget impact, clinical effectiveness, cost effectiveness, or engagement/documents (e.g. advisory board meetings, dossiers or papers). These HEOR requirements, listed for selected countries in , are important to consider when selecting DEA variables for a comparison of national health care systems.

Table 1. Health economics and outcomes research evidence requirements by country, based on advisory board meetings with experts from these countries (unreferenced).

Mental disorders, such as schizophrenia, constitute a major health economic challengeCitation10. Schizophrenia has a worldwide prevalence of approximately 20 million people, and is among the leading global causes of years lived with disability (YLD)Citation4,Citation11. Schizophrenia can take a variety of disease courses, but is generally associated with high rates of relapse, multiple episodes, and the need for lifelong treatmentCitation12–14. As well as harming patients, schizophrenia takes its emotional and physical toll on caregiversCitation15, and has a high economic burden in terms of direct health care costs and indirect costs such as absenteeism from workCitation10. Typically, health authorities do not interfere with antipsychotic prescribing or encourage the use of genericsCitation16–18, thereby showing that schizophrenia is a high priority across health care systems. Despite this economic burden, no studies have used DEA to specifically investigate the efficiency of schizophrenia health care systems, and few studies have investigated the efficiency of mental health care services. A recent systematic review found that, of 13 studies evaluating the efficiency of mental health services, only one study was internationalCitation19,Citation20. Across the mental health studies, a wide variety of inputs and outputs were used, broadly categorized into quality of care (e.g. number of specialized staff as an input), financing (e.g. direct service budget as an input), service provision (e.g. therapy hours per week as an output), and service utilization (e.g. hospital usage as an output)Citation19. Although the international study was unable to provide robust results due to a lack of good quality data, it nonetheless supported the potential of DEA to compare national mental health system performanceCitation20.

The aim of the present study was to compare the health economic efficiency of health care systems across nations, within the area of schizophrenia, using a DEA approach. The intent was not to explain differences between countries, but to systematically determine which countries are the most efficient and therefore may be used as benchmarks by policy makers. The article starts with a description of the DEA model, selection of variables, and data sources. Next, results of the DEA are presented, with countries ranked by their schizophrenia health care efficiency, followed by a discussion of the results and their limitations.

Methods

Selection of variables

The present study used a simple one input–one output model. The input was schizophrenia disease investment, defined as the cost of schizophrenia as a percentage of total health care expenditure. Total health expenditure is a common input in DEAs of health care systemsCitation5, and, in the context of mental health, many previous DEAs have used some measure of budget as an inputCitation19. As the present article specifically considers schizophrenia, schizophrenia disease investment is a more relevant input than total health expenditure.

The output was disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) per patient due to schizophrenia. A DALY is the sum of years of life lost (YLL) due to premature death (based on standard life expectancy) and YLDCitation21. YLD includes a weight factor reflecting the severity of the disease on a scale from 0 (perfect health) to 1 (dead); the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2017 study used a weight of 0.59 for residual schizophrenia and 0.78 for acute schizophreniaCitation4,Citation21. The DALY is a useful summary measure of population health because it combines data on mortality and non-fatal health outcomesCitation21. A related measure, disability-adjusted life expectancy (DALE), has been used as an output in several DEAs/frontier analyses of health care systemsCitation5.

As listed in , different countries have different HEOR evidence requirements. In the present study, schizophrenia disease investment represents budget impact, DALYs per patient represents clinical effectiveness, and DEA efficiency score represents cost effectiveness.

Each DMU represents a country, and each data point represents a specific DMU’s DALYs per patient, as a function of cost.

Data envelopment analysis

In this DEA, comparisons were made between countries by calculating the relative efficiency of each DMU relative to the ‘frontier’. The frontier was calculated by finding the maximal monotonically decreasing piecewise linear function, lower than all DALYs per patient given the disease investment (a lower linear envelope). The efficiency score (w) for a particular DMU was calculated as the ratio of the DMU to the frontier. If w = 1 for a specific DMU, then that DMU is efficient relative to other DMUs; if w < 1, the DMU is relatively inefficientCitation6.

The model assumes that the DMUs are homogenous with regard to their objectives, available resources (e.g. staff and equipment), activities undertaken and services provided, and the environments in which they operateCitation7,Citation22. DEA has been validated by several approaches including the use of hypothetical datasets with known efficiencies and inefficienciesCitation6.

The DEA was performed using Microsoft ExcelFootnotei for Office 365.

Data sources

Disease prevalence and DALYs were obtained from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) GBD 2017 studyCitation23. Gross domestic product (GDP) was obtained from the World Bank GroupCitation24. Total health care expenditure (% of GDP) was obtained from the WHO Global Health Expenditure database, via the World Bank GroupCitation25. Disease costs per patient were obtained via a literature search of the PubMed database.

The input and output variables were controlled for in terms of population/prevalence differences to ensure proper comparisons could be made across countries. If population/prevalence differences were not accounted for then larger countries would generally appear to have higher schizophrenia-related costs than smaller countries. Similarly, larger countries would be expected to have more DALYs than smaller countries, potentially distorting the view of the overall performance of each country. To fix this potential distortion, budget impact costs in each country were expressed as a percentage of total health care costs in that country, and DALYs were expressed relative to the prevalence of schizophrenia in each country. Specifically, the budget impact of schizophrenia (US$) was calculated as disease cost per patient (local currencies were converted to US$) multiplied by prevalence (number of patients). Disease investment (%) was calculated as the budget impact of schizophrenia (US$) divided by total health care expenditure (US$), times 100. DALYs per patient were calculated as DALYs divided by prevalence.

Choice of orientation

This study used output orientation, meaning that the model aimed to maximize the outputs at a given input level (as opposed to input orientation, which aims to minimize the inputs at a given output level). In the present study, output orientation assumes that schizophrenia disease investment is fixed in each country, and determines which countries were the most efficient at reducing DALYs.

Returns to scale

This study used variable returns to scale (VRS). VRS assumes that a change in inputs results in a disproportionate change in outputs (i.e. the size of a DMU influences its efficiency), as opposed to constant returns to scale (CRS), which assumes that a change in inputs results in a proportional change in outputs (i.e. the size of a DMU does not influence its efficiency).

Results

Data

Data were obtained for 44 countries across six continents. Of these, 34 countries were included in the DEA and ten countries were excluded due to incomplete data, as listed in .

Table 2. Countries included in and excluded from the data envelopment analysis.

Disease prevalence, DALYs, and GDP were collected for the year 2017; and total health care expenditure for the year 2015. Disease costs per patient were collected for the years 2002–2015, depending on what was available for each countryCitation26–30. Disease costs comprised direct health care costs (treating the disease and its consequences, e.g. physician visits, hospitalizations, and pharmaceuticals), direct non-health care costs (e.g. social services, and travel to medical appointments), and indirect costs (productivity losses due to, e.g. presenteeism, absenteeism, unemployment, informal care from family and friends, and mortality)Citation26–30. In all regions, indirect costs made up the majority of the total disease costCitation26–30.

Data are presented in full in an online interactive atlas (Disease Atlas Interactive Tool; https://institute.progress.im/en/tag-landing/disease-atlas), and are summarized in . Schizophrenia disease investment (% of total health care expenditure) was lowest in Switzerland (1.11) and highest in Thailand (6.73). DALYs per patient showed little variation across countries, ranging from 0.621 in Lithuania to 0.651 in Malaysia.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics for schizophrenia data used in the data envelopment analysis.

Efficiency scores

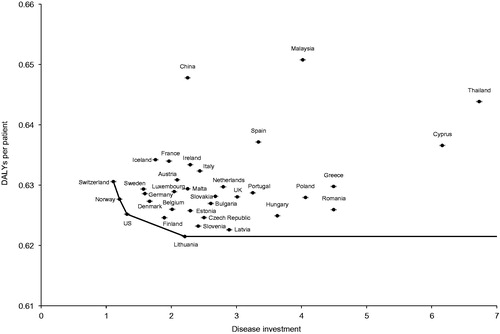

According to the DEA, schizophrenia health care was efficient (efficiency score 1) in four countries, whereas 30 countries had inefficiencies (efficiency score <1). The efficient countries were Lithuania, Norway, Switzerland and the US. These countries form the frontier, as represented in .

Figure 1. Relationship between schizophrenia disease investment (% of total health care expenditure) and DALYs per patient for 34 countries. The solid line represents the frontier developed using data envelopment analysis. Abbreviation. DALY, Disability-adjusted life year.

There was little variation in efficiency score across countries. Countries with the least efficient schizophrenia health care were Malaysia (0.955), China (0.959), and Thailand (0.965). Other countries all had efficiency scores in the range 0.970–1.000, as shown in .

Table 4. Clusters of countries with high, medium and low efficiency of schizophrenia health care.

Considering HEOR evidence requirements, countries are ranked by budget impact, clinical effectiveness and cost effectiveness in . Schizophrenia treatment had the greatest budget impact in Thailand, the greatest clinical effectiveness in Lithuania, and the greatest cost effectiveness in Lithuania, Norway, Switzerland and the US, as described above.

Table 5. Health economics and outcomes research evidence requirements parameter rankings (top 10) for schizophrenia by country.

Discussion

In this DEA, the first to investigate the health economic efficiency of health care systems within the area of schizophrenia, the most efficient countries were Lithuania, Norway, Switzerland and the US. Potentially, these should be considered ‘benchmark’ countries that can provide useful information to countries with less efficient systems. The present study did not attempt to explain differences between countries, and further work is needed to determine what aspects of health care result in high efficiency in these four countries, and how this could be applied to less efficient countries to improve their performance.

As described in , different countries have different HEOR evidence requirements, and therefore measure success in different ways. Such criteria are used to decide patient access to medicines, and are considered here from a disease perspective. The DEA efficiency score estimates may be more relevant to those countries that measure success based on clinical effectiveness, rather than on budget impact or cost effectiveness. In , countries are ranked based on the different decision-making criteria. There are many inconsistencies between the metric a country values and whether it is ranked highly in terms of performance on that metric. For example, the US – a ‘budget impact country’ – does not appear in the top ten for budget impact, but is 7th in terms of clinical effectiveness and joint 1st for cost effectiveness. In contrast, the UK – a ‘cost effectiveness country’ – does not appear in the top 10 for cost effectiveness, but is 10th in terms of budget impact. The only countries that rank in the top ten for the most relevant metric to that country are Poland (5th in budget impact), Spain (8th in budget impact) and Belgium (10th in clinical effectiveness). Possibly, budget impact countries such as Italy, Spain and the US could learn about practices in Thailand, Cyprus and Romania to become relatively more successful in cost measures. Similarly, clinical effectiveness countries such as France and Germany may benefit from studying Lithuania, Latvia and Slovenia, and cost effectiveness countries such as Sweden and the UK may benefit from studying Lithuania, Norway, Switzerland and the US, to improve in the measure that is most relevant to their country.

When considering clinical effectiveness, it should be noted that the DALYs per patient output was relatively consistent across nations despite the level of disease investment. Thus, it seems that some countries are able to generate the same level of output with a lower level of spending. This may indicate that other, non-quantitative financial factors are influencing performance. It could also potentially indicate that under-resourced countries are better at prioritizing policies and choosing essential services than over-resourced countries.

Across the world, mental health disorders are under-treated – particularly in lower and middle-income countries (LMICs)Citation31–33. Barriers to adequate mental health care in LMICs include limited health care infrastructure and trained personnel, and limited access to effective medicines, which may have high co-paymentsCitation34. These issues are starting to be addressed via national strategies to improve mental health care, such as the WHO’s mental health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) and QualityRights projectCitation34–37.

Limitations

DEA findings depend on the countries and variables that are included in the dataset. In the present study, the selection of countries was limited by the available data, and the selection of inputs and outputs was subjective. There may be data coding issues in terms of the reliability of diagnosis and classification by health care systems. For example, health care systems may not classify schizophrenia until the patient is admitted to hospital, making hospitalization the driver for costs. Furthermore, data are from multiple sources and for different years, creating uncertainty when making comparisons across countries. In particular, sources for disease cost per patient used variable methods, included different parameters in the direct costs, and included different estimates of indirect costs. In general, the reliability of the data is not known.

The GBD 2017 study used the same disability weight for the disease component of the DALY for every countryCitation4, which may contribute to the lack of variation across countries in terms of DALYs per patient. However, YLL and YLD do vary between countriesCitation4,Citation38, and the small variation in DALYs that was observed is thought to be attributed to such factors.

The DEA model assumes that the mental health care systems of different countries are homogenous, whereas there may be differences in standard of care across countries. Furthermore, no account was made in the model for environmental/lifestyle factors that may differ by country, e.g. diet, smoking rates, immunization rates, air pollution, etc.

Conclusions

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first time that DEA has been used to measure relative efficiency across countries within the area of schizophrenia with respect to costs and DALYs. The study yielded some interesting and contrasting takeaways. Despite the difference in schizophrenia disease investment across countries on the input side, there was little difference in DALYs per patient on the output side. Overall, Lithuania, Norway, Switzerland and the US were found to be efficient and can be considered ‘benchmark’ countries by policy makers for those countries that measure success based on cost effectiveness. If best practices are shared, performance can potentially be improved in the inefficient countries. However, the countries found to be efficient in terms of cost effectiveness were not necessarily the most efficient from a budget impact or clinical effectiveness perspective. It is also evident from the analysis that the countries that make decisions based on clinical effectiveness were not at the top of the clinical effectiveness rankings, and, similarly, countries that make decisions based on budget impact or cost effectiveness were not at the top of these respective rankings. This suggests that countries are not performing well from a disease perspective on the very metrics used to determine patient access from a treatment perspective.

Future work should (1) explore why some countries are more efficient than others (a qualitative assessment) in terms of identifying and describing policies in efficient countries that would help to improve schizophrenia care outcomes relative to a country’s budget in inefficient countries; (2) acquire data for the countries with incomplete data; (3) add more countries; (4) include statistical testing; (5) investigate how quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) could be generated globally within the area of schizophrenia; (6) include QALYs as an alternative output efficiency criterion; and (7) include a wider range of inputs and outputs into the model, such as economic/non-economic outcomes (e.g. incarceration, suicide, homelessness and unemployment).

Transparency

Declaration of financial/other relationships

JW, JS and BLO are full-time employees of H. Lundbeck A/S. Prior to employment with H. Lundbeck A/S, BLO was a paid consultant for H. Lundbeck A/S. He has received research grants from The TLC Foundation for Body-Focused Repetitive Behaviors and National Center for Responsible Gaming. BLO receives royalties from Oxford University Press and Johns Hopkins University Press.

JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

JW, JS and BLO contributed to the design of the study and were involved in the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. All authors participated in the drafting or the critical review of the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgements

Alice Field, BSc, of Cambridge Medical Communication Ltd (Cambridge, UK) assisted with data collection. Writing support was provided by Chris Watling, PhD, assisted by his colleagues at Cambridge Medical Communication Ltd, and funded by H. Lundbeck A/S.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, JW, upon reasonable request.

Notes

i Redmond, Washington, USA.

References

- Chisholm D, Evans DB. Improving health system efficiency as a means of moving towards universal coverage. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010; [cited 2019 Jul 31]. Available from: https://www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/financing/healthreport/28UCefficiency.pdf

- Kernick DP. Introduction to health economics for the medical practitioner. Postgrad Med J. 2003;79(929):147–150.

- Jain V. Time to take health economics seriously-medical education in the United Kingdom. Perspect Med Educ. 2016;5(1):45–47.

- GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1789–1858.

- See KF, Yen SH. Does happiness matter to health system efficiency? A performance analysis. Health Econ Rev. 2018;8(1):33.

- Bowlin WF. Measuring performance: an introduction to data envelopment analysis (DEA). J Cost Anal. 1998;15(2):3–27.

- Aziz NAA, Janor RM, Mahadi R. Comparative departmental efficiency analysis within a university: a DEA approach. Proc Soc Behav Sci. 2013;90:540–548.

- Svensson M, Nilsson FO, Arnberg K. Reimbursement decisions for pharmaceuticals in Sweden: the impact of disease severity and cost effectiveness. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33(11):1229–1236.

- Godman B, Wettermark B, Hoffmann M, et al. Multifaceted national and regional drug reforms and initiatives in ambulatory care in Sweden: global relevance. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2009;9(1):65–83.

- Olesen J, Gustavsson A, Svensson M, et al. The economic cost of brain disorders in Europe. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19(1):155–162.

- Schizophrenia key facts. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2019; [cited 2020 May 22]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/schizophrenia

- Carbon M, Correll CU. Clinical predictors of therapeutic response to antipsychotics in schizophrenia. Dialog Clin Neurosci. 2014;16(4):505–524.

- Lieberman JA, Perkins D, Belger A, et al. The early stages of schizophrenia: speculations on pathogenesis, pathophysiology, and therapeutic approaches. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50(11):884–897.

- Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T, et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for Biological Treatment of Schizophrenia, part 1: update 2012 on the acute treatment of schizophrenia and the management of treatment resistance. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2012;13(5):318–378.

- Velligan DI, Brain C, Bouérat Duvold L, et al. Caregiver burdens associated with treatment-resistant schizophrenia: a quantitative caregiver survey of experiences, attitudes, and perceptions. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:584.

- Parks J, Radke A, Parker G, et al. Principles of antipsychotic prescribing for policy makers, circa 2008. Translating knowledge to promote individualized treatment. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(5):931–936.

- Godman B, Petzold M, Bennett K, et al. Can authorities appreciably enhance the prescribing of oral generic risperidone to conserve resources? Findings from across Europe and their implications. BMC Med. 2014;12:98.

- Godman B. The need for cost-effective choices to treat patients with bipolar 1 disorders including asenapine. J Med Econ. 2015;18(11):871–873.

- García-Alonso CR, Almeda N, Salinas-Pérez JA, et al. Relative technical efficiency assessment of mental health services: a systematic review. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2019;46(4):429–444.

- Moran V, Jacobs R. An international comparison of efficiency of inpatient mental health care systems. Health Policy. 2013;112(1–2):88–99.

- Prüss-Üstün A, Mathers C, Corvalán C, et al. Introduction and methods: assessing the environmental burden of disease at national and local levels. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003; [cited 2019 Jul 31]. Available from: https://www.who.int/quantifying_ehimpacts/publications/9241546204/en/

- Dyson RG, Allen R, Camanho AS, et al. Pitfalls and protocols in DEA. Eur J Oper Res. 2001;132(2):245–259.

- Global Burden of Disease Study (GBD) data resources. Seattle (WA): Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME); 2017; [cited 2019 Dec 6]. Available from: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-2017

- Gross domestic product 2017. Washington (DC): World Bank Group; 2018; [cited 2018 Aug 6]. Available from: http://databank.worldbank.org/data/download/GDP.pdf

- Current health expenditure (% of GDP). Washington (DC): World Bank Group; 2018; [cited 2018 Aug 6]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.CHEX.GD.ZS

- Gustavsson A, Svensson M, Jacobi F, et al. Cost of disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21(10):718–779.

- Zhai J, Guo X, Chen M, et al. An investigation of economic costs of schizophrenia in two areas of China. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2013;7(1):26.

- Wu EQ, Birnbaum HG, Shi L, et al. The economic burden of schizophrenia in the United States in 2002. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(9):1122–1129.

- Teoh SL, Chong HY, Abdul Aziz S, et al. The economic burden of schizophrenia in Malaysia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:1979–1987.

- Jin H, Mosweu I. The societal cost of schizophrenia: a systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2017;35(1):25–42.

- Thornicroft G, Chatterji S, Evans-Lacko S, et al. Undertreatment of people with major depressive disorder in 21 countries. Br J Psychiatry. 2017;210(2):119–124.

- Wang PS, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, et al. Worldwide use of mental health services for anxiety, mood, and substance disorders: results from 17 countries in the WHO world mental health (WMH) surveys. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):841–850.

- Kohn R, Saxena S, Levav I, et al. The treatment gap in mental health care. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82(11):858–866.

- Godman B, Grobler C, Van-De-Lisle M, et al. Pharmacotherapeutic interventions for bipolar disorder type II: addressing multiple symptoms and approaches with a particular emphasis on strategies in lower and middle-income countries. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2019;20(18):2237–2255.

- World Health Organization. mhGAP intervention guide for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non-specialized health settings: mental health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) – version 2.0. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2016; [cited 2020 May 20]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail/mhgap-intervention-guide—version-2.0

- World Health Organization. WHO QualityRights: service standards and quality in mental health care. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2020; [cited 2020. May 20]. Available from: https://www.who.int/mental_health/policy/quality_rights/infosheet_hrs_day.pdf

- World Health Organization, Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. Improving access to and appropriate use of medicines for mental disorders. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017; [cited 2020 May 20]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/254794/1/9789241511421-eng.pdf

- GBD 2017 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1736–1788.