Abstract

Aim

To understand the financial impact of health system adoption of novel heart failure medications under US alternative payment models (APMs).

Materials and methods

This study used a decision tree model to assess the financial impact of health system adoption of sacubitril/valsartan to treat acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF). A comparator scenario modeled current health care utilization and cost for treating hospitalized ADHF patients with angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) or angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARB). The study then measured the impact of adopting sacubitril/valsartan to treat ADHF on health system economic outcomes. Differences in treatment efficacy were based on the PIONEER-HF clinical trial. The financial impact of changes in patient outcomes under the sacubitril/valsartan and ACEi/ARB arms was assessed across three APMs: the Medicare Shared Savings Program, Bundled Payments for Care Improvement, and fee-for-service payments adjusted according to the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program.

Results

Sacubitril/valsartan reduced re-hospitalizations after an initial ADHF admission by 46.3% for individuals aged 18–64 years and 23.4% for individuals aged ≥65 years. Health systems’ financial benefit of adopting sacubitril/valsartan was $740 per ADHF case per year (PCPY). Savings were larger for patients aged ≥65 years ($803 PCPY) compared to those <65 years ($653 PCPY). The majority of the health system financial benefit came from changes in APM bonus and penalty reimbursements. Value-based payments from the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program ($1,190 financial gain PCPY) and the Bundled Care Payment Improvement Initiative ($645 financial gain PCPY) produced larger financial benefits than participation in the Medicare Shared Savings Program ($253 financial gain PCPY).

Limitations

The model uses clinical trial data, which may not reflect real-world outcomes. Further, the financial implications were modeled based only on three widely used APMs.

Conclusion

Sacubitril/valsartan adoption decreased hospitalizations and led to a positive net financial impact on health systems after accounting for APM bonus payments.

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) currently affects more than 6 million patients in the US and is the primary diagnosis for more than 1 million hospital admissions each yearCitation1,Citation2. Of these HF admissions, approximately half are classified as acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF), with an annual incidence of 11.6 ADHF hospitalizations per 1,000 persons aged 55 and olderCitation3. Hospitalization for ADHF is a strong predictor of readmission and post-discharge deathCitation4. The average per patient cost of an ADHF-related hospital admission is more than $12,000 in the US with high post-acute care costs as wellCitation5.

The treatment guidelines for ADHF have not changed significantly in over 40 years: inotropes and vasodilators are utilized for hemodynamic support while intravenous diuretics aid in decongestion [Citation6–8]. Sacubitril/valsartan is a relatively novel treatment indicated for patients with reduced ejection fraction (EF) heart failure and acts as an angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor. The PARADIGM-HF clinical trial demonstrated that sacubitril/valsartan is superior compared to enalapril (a commonly used ACEi) in lowering risk of cardiovascular-related death and hospitalization in ambulatory outpatients with HFCitation9,Citation10. More recently, the PIONEER-HF clinical trial demonstrated that sacubitril/valsartan is superior to enalapril in lowering risk of cardiovascular-related death and re-hospitalization in patients hospitalized with ADHFCitation11,Citation12.

This study aimed to predict how the adoption of sacubitril/valsartan for the treatment of ADHF would affect a health system’s finances. Under traditional fee-for-service systems, the impact of sacubitril/valsartan adoption would depend both on the change in the volume of services provided by the health system and the margin of each of these services. In recent years, however, many payers have implement value-based provider bonus payments and penalties in hopes of achieving the triple aim of improving patient experience and health outcomes while reducing costCitation13,Citation14. One common approach to incentivize providers to align with payer-specific goals is to link provider payments to quality and/or cost outcomes. These value-based payment approaches—known as alternative payment models (APMs)—are increasingly common. Between 2012 and 2019, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) implemented eight separate value-based payment programs for providersCitation15. By 2018, 61% of all US healthcare payments were paid based on some sort of APM; further, 91% of payers believe that APM activity will increase in the futureCitation16. APMs have diverse manifestations such as quality- or cost-based payment adjustments to fee-for-service reimbursement, financial bonuses (or penalties) based on sharing savings (or losses), making provider payments fully or partially capitated, and othersCitation17.

To explore how these dynamics affect provider decision-making, this study examines a case study of health systems’ decision to adopt sacubitril/valsartan for the treatment of ADHF. First, current treatment practices likely to be impacted by sacubitril/valsartan were modeled. Second, clinical trial data was used to measure the efficacy of sacubitril/valsartan on health care utilization compared to traditional, generic renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibition therapy, namely generic ACEi or ARB. Finally, the total economic impact on health systems was calculated by incorporating bonus payments and penalties from three common APMs: the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP), the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) Initiative, and fee-for-service payments with adjustments for the Hospital Readmission Reductions Program (HRRP).

Methods

This study used a three-part decision tree model to describe the financial impact on health systems of adopting sacubitril/valsartan for the treatment of adults hospitalized for ADHF in the USA. Following International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) guidelinesCitation18, decision trees are recommended for models with short time horizons and limited outcomes; the model fits both criteria with a time horizon of 60 days in the base case and a focus on hospital readmissions, emergency department visits and associated costs. First, the model analyzed a comparator scenario that assessed the financial impact on health systems of treating ADHF patients with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) or angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs). Second, results from the PIONEER-HF clinical trial of ADHF patients were used to model a treatment scenario to determine how healthcare utilization (i.e. re-hospitalization and emergency department [ED] visit frequency) would change after adopting sacubitril/valsartan compared to treatment with generic ACEi or ARBsCitation12. Lastly, model assessed how changes in patient healthcare utilization resulting from treatment with sacubitril/valsartan affected health system finances relative to the comparator scenario.

The financial impact was modeled based on three commonly used APMs: MSSP, BPCI, and fee-for-service with HRRP. Health systems participating in MSSP receive a bonus payment if overall spending for their assigned patients falls below an annual spending target called a “benchmark” and the health system meets a series of quality thresholdsCitation19. BPCI allows hospitals or physician group practices to assume responsibility for bundles of care with most bundles covering inpatient hospital care for orthopedic and cardiac conditionsCitation20. HRRP applies only to hospitals and reduces their reimbursement if the hospitals have more 30-day readmissions than expected (i.e. excess readmissions) across six common conditions, one of which is heart failureCitation21.

Comparator scenario

To build the model, clinical trial health outcomes of adult patients with ADHF initiating ACEi or ARB therapy in a hospital setting were used to calculate the resulting costs and reimbursements to a health system in a fee-for-service model and obtain the net financial impact. Treatment guidelines indicated that ACEi and ARBs are commonly used to treat reduced EF heart failureCitation22. The time horizon included the initial hospitalization, plus 60 days postdischarge in the base case. contain a full list of the model parameters.

Table 1. Input parameters for model of adults recently hospitalized for acute decompensated heart failure.

Treatment scenario

The treatment (i.e. sacubitril/valsartan) arm calculated the net financial impact of adopting sacubitril/valsartan. This scenario assumes that all patients initially hospitalized with ADHF were treated with sacubitril/valsartan compared to the comparator scenario where half of patients receive an ACEi and the other half an ARB. The change in health outcomes for patients treated with sacubitril/valsartan were obtained from the treatment arm of the PIONEER-HF trial relative to the comparator arm. Specifically, sacubitril/valsartan reduced re-hospitalizations after an initial ADHF admission by 46.3% for individuals aged 18–64 years and 23.4% for individuals aged ≥65 yearsCitation12,Citation23. This percentage change was then applied to the number of events in the model comparator arm (as described above) to estimate the number of events per person in the model treatment arm.

Population parameters

In line with the PIONEER-HF clinical trial, the population of interest included HF patients with a reduced EF stabilized during hospitalization for ADHF. Estimates from the literature were used to determine the size of this population within a typical health system. The patient panel for the health system was assumed to be 100,000 adults (i.e. ≥18 years of age), of which, 20.6% were ≥65 years of age based on US Census Bureau figures from 2018Citation24. Pediatric patients (aged <18 years) were excluded from the analysis. Age-adjusted heart failure prevalence was obtained from the literature (1.50% for those 18–64 years old and 7.94% for those ≥65 years old)Citation25,Citation26, and 50% of those cases were expected to be reduced EF HFCitation26,Citation27. The age-adjusted annual HF hospitalization rate was 0.116 per HF patient aged 18–64 per year and 0.118 for those aged ≥65 years old; 75% of index hospitalized HF patients were assumed to have ADHFCitation23. The product of these estimates was calculated to obtain the size of the expected number of patients per year with reduced EF HF hospitalized for ADHF within a typical health system.

Health outcomes

Treatments and health outcomes for the model were obtained from the PIONEER-HF clinical trialCitation11,Citation12. Given the treatment landscape for heart failure, the treatments of interest for the comparator scenario were ACEi and ARBs; however, data reported by the clinical trial only captured ACEi efficacy. The analysis assumed the efficacy of ARBs to be equal to that of ACEi, based on a previous network meta-analysisCitation28. Utilization rates of ACEi and ARBs were assumed to each be 50%, however the results are not sensitive to this assumption.

The healthcare resource utilization outcomes of interest were changes in the number of hospitalizations, length of stay of re-hospitalizations, and number of ED visits. These outcomes were HF-related and measured separately for patients aged <65 years and those ≥65 years based on a sub-group analysis from the sacubitril/valsartan and enalapril arms of PIONEER-HF trial; the measurement period was from the initial ADHF hospital admission discharge date (median index hospitalization length of stay = 6 days) to 50 days post discharge. The base case reports results for a 60-day post-initial-discharge time horizon.

APMs vary in the time periods they cover: 30 days post discharge for HRRP, 90 days postdischarge for BPCI, and 1 year irrespective of discharge date for MSSP. However, a 60-day postdischarge time period was selected because: (i) that is the approximate time period for which data from the PIONEER-HF clinical trial was available, and (ii) it falls within the range of time horizon for the 3 APMs considered. For the comparator scenario, the number of hospitalizations and ED visits per patient was converted to event rates by identifying the number of total events per person that occurred out of all patients in the enalapril arm of the PIONEER-HF trial over a 50-day postdischarge time horizon. Event rates were calculated separately for days 1–30 days after discharge and 31–50 days after discharge. The percentage change in the number of re-hospitalizations and ED visits between the sacubitril/valsartan arm and the enalapril arms of the PIONEER-HF trial was used to parameterize the sacubitril/valsartan arm in this model. As the PIONEER-HF trial only had 50 days postdischarge follow-up, we conservatively assumed that between days 51–60 postdischarge all patients transition to the comparator scenario and event rates in this time period were equal to those through day 50 as measured in the enalapril arm of the PIONEER-HF trial. While event rates were used to calculate most outcomes, for the HRRP, we needed to calculate the proportion of patients with a readmission during a 30-day period, and assumed a proportional reduction in this probability.

Costs and reimbursements

Reimbursement rates for acute heart failure admissions were initially calculated based on Medicare reimbursement for acute HF admissions. Under the Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS), health systems are reimbursed a fixed amount for severity-adjusted Medicare Severity-Diagnosis Related Groups (MS-DRGs). The reimbursement rates for admissions with major complications, complications and no complications (i.e. MS-DRG 291, 292, and 293) were used and a weighted average was calculated based on the relative frequency of such admissions in the fiscal year (FY) 2016 Medicare inpatient charge fileCitation29. This reimbursement is expected to cover the costs of pharmaceutical treatments required while being receiving inpatient treatment.

Differences in reimbursement rates across insurers were incorporated to estimate the cost and reimbursement for nonelderly adults (i.e. aged 18–64 years). First, data from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) was used to estimate the share of individuals who were insured by commercial plans, (69.7%), Medicaid (17.5%) or who had other insurance or were uninsured/self-pay (12.8%)Citation30. Next, the relative reimbursement rate of commercial payers, Medicaid and the uninsured relative to Medicare were measured [Citation31–34]. Finally, the reimbursement for the nonelderly was calculated as a weighted average of these reimbursement rates, where the weights were the share of adult, non-elderly individuals in each of the three insurance categories considered.

Emergency department reimbursement and cost were estimated similarly. First, an estimate of the cost of ED visits for HF was identifiedCitation35. In order to estimate Medicare reimbursement for ED visits among the elderly, it was assumed that HF-related ED visits had profit margins equal to those of HF-related admissions reimbursed by Medicare. Next, the same reimbursement multiplier described above was used for nonelderly HF hospital stays.

The cost of pharmaceuticals was estimated using the wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) from the ProspectoRx database. It was assumed that the health system was not responsible for any outpatient pharmacy costs.

All costs were inflated to 2018 USD using the Bureau of Labor Statistics Medical Care version of the Consumer Price Index (CPI-Medical Care). Calculations were performed in Excel 2016.

Net financial impact calculation

The net financial impact was calculated as the difference between the total costs and total reimbursements plus any bonuses received from APMs. Since the details of most commercial APM structures are not publicly available, it was assumed that APMs for the commercially insured population offer incentive structures similar to those available for the Medicare population although fee-for-service reimbursement would occur at commercial rather than Medicare rates. Total costs included the costs of the initial hospitalization, readmissions, ED visits and inpatient pharmacy. Total reimbursements included reimbursements for the initial hospitalization, readmissions and ED visits plus any financial incentive payments (or penalties) to health systems from APMs. The financial incentive payments include any APM reimbursement not directly for services including HRRP penalties (i.e. a negative payment) and MSSP shared savings bonus payments or penalties. Since avoided readmissions can free up hospital capacity for additional hospitalizations, a readmission replacement mechanism was modeled. In the base case, it was assumed that 100% of avoided readmissions could be replaced by another readmission of any type (i.e. cardiac- or non-cardiac-related). The reimbursement for these replacement hospitalizations was assumed equivalent to all-cause hospital reimbursement calculated from the Medicare 2016 inpatient charge file. The reimbursement parameter and hospital margins from the Medicare Payment Advisory Committee (MedPAC) 2019 report were used to calculate the cost of replacement readmissionsCitation36. To obtain per-ADHF case per-year (PCPY) results, the net financial impact was divided by the expected yearly number of patients within a health system with an initial ADHF hospitalization.

APM descriptions and model calculations

To calculate the impact of the adoption of sacubitril/valsartan, the difference in the net financial impact between the comparator and treatment models was calculated for three commonly used APMs: Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP)Citation37,Citation38, Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) InitiativeCitation39 and fee-for-service with the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP)Citation40. Following current reimbursement trendsCitation41, the modeled health system had 43.1% of its payments from fee-for-service, 35.8% from accountable care organization (i.e. Medicare Shared Savings) and 21.2% from bundled payments (i.e. BPCI).

The first APM modeled, the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP), was designed to provide a financial incentive for health systems to reduce cost and improve quality. In 2019, 518 accountable care organizations (ACOs) covering 10.9 million assigned Medicare beneficiaries participated in MSSPCitation42. Under this APM, annual costs for an ACO are compared to a benchmark cost level, and a percentage of the shared savings from reduced readmissions is shared with the ACO. ACOs have multiple participation options, including both one-sided (share financial benefits only) and two-sided (potential for sharing of financial benefits and losses)Citation19. These ACOs share the savings that result from reduced healthcare utilization. Payments made to health systems under MSSP were nearly $800 million in 2017Citation42. The model in this study applies MSSP Level D; thus, health systems share 50% of any cost savings and also bear 50% of any additional medical cost.

To calculate the bonus payment to a health system under the MSSP, the difference in reimbursements made by the payer under the comparator and treatment models was measured to identify the fraction of savings that would be shared with the health system. Under the MSSP, savings are typically measured over a one-year period; however, a 60-day time horizon is reported in the base case. Furthermore, in the absence of information on quality, it was assumed that there are no changes in quality metrics resulting from adoption of sacubitril/valsartan. Then, a two-sided 50% shared savings model was applied whereby health systems recoup 50% of change in reimbursements under the treatment scenario compared to the comparator scenario.

The Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiative (BPCI), the second APM modeled, is an episode-based APM in which Medicare retroactively reimburses the health system a single flat payment for all Part A and B services provided during the specified period rather than individually for each service provided. Under the new BPCI Advanced program, a BPCI episode is initiated by an Anchor Stay or Anchor Procedure, which triggers the start of a 90-day episode of care. There are 34 types of Anchor Stays Anchor Procedures that trigger a BPCI episode. During this episode of care, a payment covers all Medicare Part A and B services provided both during the Anchor Stay/Anchor Procedure as well as all Part A and B services provided during the 90 days following the Anchor Stay/Anchor Procedure, including outpatient and hospital services. All services are included in the episode even if they are not directly related to the illness causing the Anchor Stay/Anchor ProcedureCitation20. BPCI aims to incentivize hospitals to reduce the cost of care post-acute care and promote efficient use of resourcesCitation43. If health systems are able to reduce healthcare spending after the initial episode of care—such as for hospital readmissions, skilled nursing facility utilization, or home health care—they stand to benefit financially. If on the other hand spending is greater than expected, then the health system loses money.

To assess the impact of adopting sacubitril/valsartan under the BPCI, the difference in net financial impact for the treatment (i.e. sacubitril/valsartan) and comparator (ACEi/ARB) arms was calculated. As BPCI uses flat rate reimbursement, there is no difference in reimbursement between the treatment and comparator model arms; the net financial impact is simply the difference in cost to the health system from changing rates of hospitalizations, and ED visits during the 90 days after an ADHF episode of care. Under the BPCI, an episode of care is typically 90 days from hospital admission, but 60-day postdischarge results are reported to maintain consistent time horizons across APMs in the base case. It is assumed that there is no difference in health system reimbursement or cost for days 51–60 in the model.

Finally, the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP) was the third APM modeled. HRRP was designed to reduce excess healthcare utilization by penalizing hospitals through lower reimbursements if the hospital exceeds a threshold number of readmissions. A hospital’s readmission rate, however, is based on readmissions for six common conditions: acute myocardial infarction, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, pneumonia, coronary artery bypass graft surgery, and elective primary total hip arthroplasty and/or total knee arthroplastyCitation21. Hospitals are penalized for all admissions when readmissions for these six types exceed the risk-adjusted expected count.

The model measures the change in HF readmission rates when a health system treats ADHF patients with sacubitril/valsartan compared to an ACEi or ARB. The overall readmission rate is a payment-weighted average of the excess readmission rates for each of these six conditions. While the overall excess readmission rate is calculated based on data from only the six relevant conditions, HRRP payment adjustments are applied to all of the hospital’s admissions. Specifically, while HF only made up 4% of all Medicare admissions in 2019, HF admissions comprised up 22% of the admissions used to calculate the HRRP excess readmissions ratioCitation44. Thus, changes in heart failure readmissions disproportionately influence the calculated HRRP excess readmission rate, which is used to adjust reimbursement for all of a health system’s admissions. A maximum payment penalty of 3% was considered per the HRRP regulationsCitation21.

To estimate how the use of sacubitril/valsartan would affect reimbursement under the HRRP, the model first estimated the change in ADHF readmissions for the typical hospital. It was assumed that half of HF readmissions were for ADHFCitation3. The change in excess readmission ratio was calculated holding constant readmissions for non-ADHF heart failure admissions and for the other five admission types considered for HRRP. Once the excess readmission ratio was calculated, the change in payment rates was estimated assuming that hospitals were at the threshold where the HRRP penalties would be binding (i.e. at 0% excess readmission ratio). The total financial impact per ADHF admission for the hospital was equal to the HRRP penalty percentage, multiplied by the average reimbursement for any admission ($16,325), divided by the share of all hospital reimbursement that come from ADHF admissions (4.3%).

The model was built using Microsoft Excel 2019 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Tornado plots for the deterministic sensitivity analysis was implemented using the Sensitivity Toolkit package (http://mba.tuck.dartmouth.edu/toolkit/).

Scenario and sensitivity analyses

A series of scenario and sensitivity analyses were conducted to identify the impact of changes in model assumptions and key model parameters on the net financial impact to a health system. First, although the base case model assumed that the BPCI bundled payments covered a 60-day postacute period, BPCI also for 30 and 90-day bundled payments as wellCitation45. Thus, the impact of using a 30-day time horizon was explored. A 90-day BPCI program was not modeled as efficacy data beyond 50 days after index hospital discharge was not captured in the PIONEER-HF trial and our model assumes no efficacy in this period. Second, the outcomes for all-cause events were calculated, unlike the base case which reported results for HF events only. The PIONEER-HF trial only reported HF-related ED visits and it was therefore conservatively assumed that the number of all-cause ED visits was equal to the number of HF-related ED visits. Third, the impact of the Enhanced Track for MSSP was assessed, in which it was assumed that ACOs share 75% of any financial savings (i.e. cost reduction) rather than the 50% rate used in the base case.

A fourth analysis evaluated the impact of incorporating the changes in readmission length of stay on health system finances. Cost for an additional inpatient day was based on data from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) National Inpatient Sample (NIS) data. In the PIONEER-HF trial, the length of the index admission was nearly identical across arms (median = 6 days in both arms) as dictated by clinical trial protocolCitation12. Thus, the impact of mean and median differences in the length of stay of any subsequent re-hospitalization from the PIONEER-HF clinical trial was assessed, including the HF-hospitalization and median length of stay forCitation35.

A fifth analysis tested the readmission replacement assumption via two scenario analyses. In the first scenario, total financial impact was assessed assuming a 0% value for the readmission replacement parameter that was set to 100% in the base case; this scenario shows how model results are affected if hospitals are operating below full capacity and none of the avoided rehospitalizations were replaced by other hospital admissions. In the second scenario, it was assumed that 100% of avoided readmissions were replaced with cardiac-related hospitalizations as opposed to any hospitalizations as in the base case.

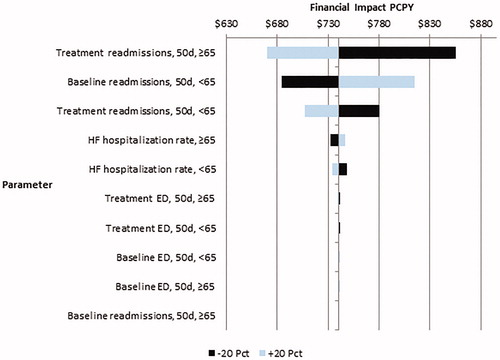

Lastly, one-way sensitivity analysis was conducted by sequentially varying uncertain clinical parameters—comparator arm readmission rate and change in readmission rate—by ±20%. A tornado diagram is reported to illustrate how sensitive model outcomes are to sequential variation in individual parameter values.

Results

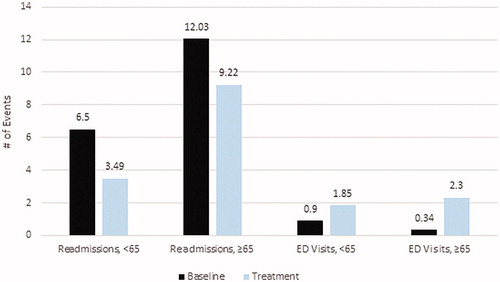

For a health system with a population of 100,000 patients, the model estimated that 79,570 were aged 18–64 years and 20,430 over 65 years old resulting in 52 and 72 ADHF hospitalizations per year, respectively. displays age-stratified health outcomes through 50 days postdischarge for the comparator and treatment models. Relative to the comparator scenario, a health system that adopted sacubitril/valsartan for treatment during ADHF hospitalization reduced re-hospitalizations by 3.01 (46.3%) for adults <65 years and by 2.81 (23.4%) in adults ≥65 years. For HF-related ED visits, sacubitril/valsartan adoption increased the number of ED visits. For adults <65, sacubitril/valsartan increased ED visits by 0.95 (106%); for adults aged ≥65 years the corresponding figure was a 1.96 increase (576%).

Figure 1. Age-stratified health outcomes through 50 days postdischarge of initial ADHF hospitalization for an IDN that utilizes ACEi or ARB (comparator) compared to one that adopts sacubitril/valsartan (treatment).

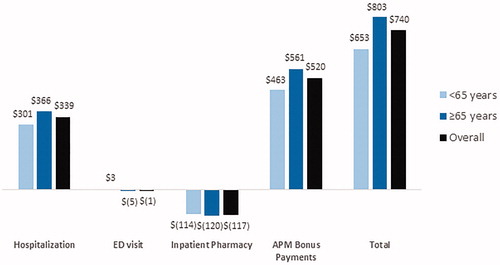

Adoption of sacubitril/valsartan led to a positive financial gain for health systems. shows the financial impact for a health system weighted by the average mixture of APM coverage broken down by financial category and stratified by age. Overall savings were $740 PCPY. Savings were larger among adults ≥65 years hospitalized with ADHF ($803 PCPY) compared adults aged <65 years ($653). Inpatient pharmacy cost increased and had a negative financial impact (–$117 PCPY) and were relatively consistent across age groups. ED visits had a negative financial impact (–$1 PCPY) but this result was small in magnitude across both age groups. The consistent reduction in re-hospitalization from sacubitril/valsartan adoption translated to modest financial gains ($339 PCPY) and were largest in the ≥65 population ($147 PCPY).

Figure 2. Financial impact for an IDN weighted by a typical mixture of APM coverage broken down by financial category and stratified by age.

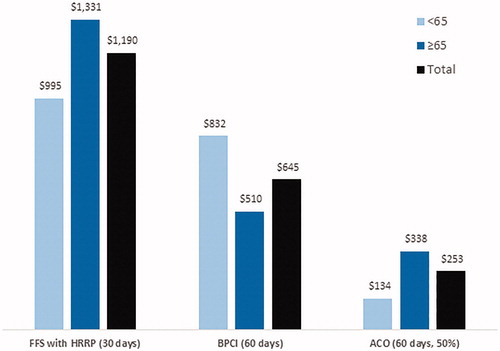

The majority of positive financial impact from sacubitril/valsartan adoption was due to APM bonus payments ($520 PCPY), especially in the ≥65 population ($561 PCPY). Most of these bonus payments were generated from the FFS with HRRP program reimbursement scheme. shows the financial impact of sacubitril/valsartan adoption stratified by APM type and age. FFS with HRRP resulted in $1,190 in average savings per ADHF case per year, with the most positive impact in adults aged ≥65 years ($1,331 PCPY). For health systems participating in the BPCI initiative with a 60-day post-initial hospitalization capitated payment, savings were $645 PCPY, with the most positive impact among adults aged <65 years ($832 PCPY). Under the ACO model, sacubitril/valsartan adoption had a positive financial impact ($253 PCPY); results were less positive in the <65 population ($134 PCPY) while those ≥65 had a positive impact ($338 PCPY).

Scenario and sensitivity analysis

A 30 days post-discharge model horizon for the BPCI and MSSP APMs yielded slightly lower profits compared to the base case (). For a health system weighted by a typical mixture of APM coverage, the PCPY financial impact was $664 compared to $740 in the preferred base case specifications. Financial gains from reduced hospitalizations were lower compared to the base case ($261 PCPY vs $339, respectively) and not quite offset by savings in inpatient pharmacy costs.

Table 2. Scenario analysis of the financial impact of sacubitril/valsartan adoption on IDN profits under typical APM coverage.

When all-cause hospital readmissions and ED visits were considered, the financial impact of adopting sacubitril/valsartan increased to $941 PCPY, an increase of 27.2% relative to the base case that only considered HF-related utilization. The improved financial result was driven by a combination of gains due to reduced hospitalization ($366 PCPY) and increased APM bonus payments ($704 PCPY).

Results for the scenario that analyzed the Enhanced Track for MSSP (75% sharing instead of 50% as in the base case) were slightly more positive ($7619 PCPY) compared to the base case. The marginal overall financial gain for the health system due to this scenario is consistent with the slight increase in APM bonus payments due to the higher sharing percentage.

Consistent with the base case, the scenario analysis with cost per hospitalization calculated based on readmission length yielded a positive financial impact due to sacubitril/valsartan adoption for a health system weighted by a typical mixture of APM model coverage. The median readmission length parameter yielded a more positive impact than the mean readmission length of stay ($725 PCPY vs. $389, respectively) as the difference in mean length of stay between the PIONEER-HF sacubitril/valsartan and ACEi arms was larger than the median difference. As expected, changing how the hospitalization cost parameter was calculated only impacted hospitalization costs and therefore all changes in financial impact due to incorporation of LOS reflect changes in hospitalization costs.

Scenarios under alternative readmission replacement assumptions yielded slightly more negative results compared to the base case. When 0% readmission replacement was assumed, the total financial impact was $520 PCPY. When replacement readmissions were cardiac only with 100% replacement, the total financial impact was $578 PCPY. These results are consistent with expectations since replacement readmissions generate profit for the health system and admissions of any type generate more profit than cardiac admissions.

One-way sensitivity analysis confirmed that results were relatively robust to sequential variation of key clinical parameters. Alteration of parameters generally produced a financial benefit ranging between $447 to $588 PCPY, with most results showing a financial gain to health systems of more than $500 PCPY. is a tornado diagram showing how financial impact for a health system weighted by a typical mixture of APM coverage varies when clinical efficacy parameters are varied by ±20%. Overall, the positive financial impact of sacubitril/valsartan adoption is robust to variation in all parameters, with the positive financial impact remaining over $445 PCPY even when the sacubitril/valsartan 50-day readmission rate among the elderly was increased by 20% relative to the base case value. Model results were not sensitive to any of the ED-related parameters, with financial impact ranging by $2.78 for the most sensitive ED parameter (sacubitril/valsartan ≥65 50-day ED visit rate).

Discussion

This model predicts that the adoption of sacubitril/valsartan will lead to positive net financial impacts for US health systems. Specifically, a health system reimbursed under three widely used APMs is likely to see a financial benefit of $740 PCPY. These benefits were somewhat higher for elderly patients with an ADHF admission ($803 PCPY) compared to those aged 18–64 ($653 PCPY). Further, the vast majority of health systems’ overall financial benefit came from medical cost reduction in the case of BPCI, shared savings bonus payments under MSSP and avoidance of reimbursement penalty against all hospital admissions under HRRP. In short, sacubitril/valsartan’s ability to reduce hospitalizations led to a financial benefit for US health systems under these three widely used APMs.

To understand why this is the case, consider that a health system’s treatment selection is a function of patient health outcomes and profitCitation46,Citation47. Under a strictly fee-for-service model, decreases in re-hospitalizations are financially costly for health systems—assuming hospitalizations are profitable—due to reduced reimbursements. In these cases, health systems can trade off the marginal gain to patient health against the marginal impact on their profit. In this study, accountable care organizations—modeled through MSSP—provided a small positive financial incentive to adopt sacubitril/valsartan; while reducing re-hospitalizations also means reducing revenue from reimbursements, this financial loss is more than offset by shared savings payments. Sacubitril/valsartan was more attractive under BPCI since 100% of any cost-offsets after the initial treatment episode were captured by the health system. Notably, the financial incentivizes for health systems to adopt of sacubitril/valsartan were strongest for HRRP in large part because readmission reductions penalty was calculated across only 6 target conditions—of which heart failure is one—and the calculated excess readmissions ratio affects reimbursement for all of a health system’s hospital admissionsCitation21. Studies on optimal payment systems for physicians have also shown that bonus payments may need to be large to adequately incentivize physicians to adopt innovations that reduce the number of previously profitable health care services a patient “needs.”Citation48

In practice, it is unclear whether APMs have incentivized or discouraged the adoption of new pharmaceuticals. APMs may incentivize adoption when new drugs tend to lower non-drug spendingCitation49,Citation50. One study of Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts’s global budget-based payment system, the Alternative Quality Contract (AQC), found no statistically significant difference in pharmaceutical useCitation51. In the case of sacubitril/valsartan, its value in reducing rate of hospital readmissions and associated medical costs[Citation12,Citation52] is well aligned with the financial incentives of the three widely implemented APMs (e.g. almost all hospitals are subject to HRRP), which makes a strong financial case for hospitals and IDNs for optimizing utilization of sacubitril/valsartan for eligible HF patients. However, some new pharmaceuticals may improve patient quality of life or survival without corresponding reductions in utilization or cost and thus may result in negative financial impacts for health systems, particularly if these are inpatient treatments. Further, some treatments may improve patient clinical outcomes or functional status in ways that are not captured by the quality metrics in use by APM. For example, sacubitril/valsartan clinical trial showed a reduction in mortality among ADHF patientsCitation9,Citation10, but many APM do not incorporate mortality into their quality metrics or bonus payments.

This study has a number of limitations. First, treatment effectiveness in the real-world was assumed equivalent to treatment efficacy observed in the PIONEER-HF clinical trial. Second, the model is only able to capture the utilization-based outcomes reported in the PIONEER-HF clinical trial, which include hospitalizations, ED visits, and pharmacy costs for the treatments in the trial. Thus, the model simplifies patient engagement with the healthcare system by only focusing on a handful of outcomes while ignoring other potential costs (e.g. treatment of adverse events, indirect costs) or non-cost outcomes (e.g. mortality). Third, the model simplifies the commercial APM environment. In practice, commercial APMs are diverse, but many of the APM details for commercial insurers are not reported publicly. Recent research, however, indicates that many commercial payers use similar APM structures to Medicare in the case of ACOsCitation53, and the model did incorporate differences in reimbursement rates by payer. Fourth, the model did not include the impact of the adoption of sacubitril/valsartan on health system financial performance based on APM quality metrics. Some APMs (e.g. MSSP and Medicare’s Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program) allow quality metrics to affect reimbursement, but due to the large number of quality measures, improvement in quality for any single measure does not have a large impact on reimbursement ratesCitation54. Fifth, there were few emergency department visits in the PIONEER-HF trial, and thus ED-related parameter estimates are uncertain. However, because ED visits are low cost relative to re-hospitalizations, this uncertainty likely had a small impact on the results. Sixth, our base case model utilized a 60-day time horizon which is less than the actual evaluation windows for BPCI (90 days) and MSSP (1 year); therefore, our results may underestimate the potential savings resulting from sacubitril/valsartan adoption under these two APMs. Sixth, the model assumed that patients were not previously using sacubitril/valsartan in the outpatient setting; in practice, some patients may already be using sacubitril/valsartan to treat chronic heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. Lastly, the model is a partial equilibrium model of one health system adopting sacubitril/valsartan. If multiple health systems adopt sacubitril/valsartan at the same time, then any bonuses or penalties measured on a relative scale or subject to budget neutrality adjustments may be small since the outcomes for all health systems would improve simultaneously.

Conclusion

The adoption of sacubitril/valsartan to treat ADHF increased net financial benefits to the health system after incorporating alternative payment model reimbursements. When considering adoption of a new treatment, health systems may consider not only health benefits to the patient and direct financial impacts, but also how bonus payments and penalties from APMs may affect clinician decisions to prescribe.

Transparency

Declaration of financial/other interests

JS is a current and MB and EA are former employees of PRECISIONheor. JS hold equity in Precision Medicine Group, PRECISIONheor’s parent company. XS is an employee of Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. SP was an employee of University of Maryland Baltimore and provided services to Novartis Pharmaceuticals during the conduct of the study. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

Conception and design, or analysis and interpretation of the data: JTS, MSB, ERA. Drafting of the paper or revising it critically for intellectual content: JTS, MSB, ERA. Final approval of the version to be published: JTS, MSB, ERA. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Previous presentations

None.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jesse Sussell for his contributions in the design and implementation of the modeling, and Jessi Tobin for providing assistance supporting this research.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135(10):e151.

- Blecker S, Paul M, Taksler G, et al. Heart failure-associated hospitalizations in the United States. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(12):1259–1267.

- Chang PP, Chambless LE, Shahar E, et al. Incidence and survival of hospitalized acute decompensated heart failure in four US communities (from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study). Am J Cardiol. 2014;113(3):504–510.

- Solomon SD, Dobson J, Pocock S, et al.; Candesartan in Heart failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and Morbidity (CHARM) Investigators. Influence of nonfatal hospitalization for heart failure on subsequent mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2007;116(13):1482–1487.

- Nicholson G, Gandra SR, Halbert RJ, et al. Patient-level costs of major cardiovascular conditions: a review of the international literature. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2016;8:495–506.

- Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al.; Document Reviewers. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18(8):891–975.

- Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(6):776–803.

- Ramírez A, Abelmann WH. Cardiac decompensation. N Engl J Med. 1974;290(9):499–501.

- McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, PARADIGM-HF Committees and Investigators, et al. Dual angiotensin receptor and neprilysin inhibition as an alternative to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in patients with chronic systolic heart failure: rationale for and design of the Prospective comparison of ARNI with ACEI to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and morbidity in Heart Failure trial (PARADIGM-HF). Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15(9):1062–1073.

- McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, et al. Angiotensin–neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(11):993–1004.

- Velazquez EJ, Morrow DA, DeVore AD, et al. Rationale and design of the comparison of sacubitril/valsartan versus enalapril on effect on nt-pRo-bnp in patients stabilized from an acute Heart Failure episode (PIONEER-HF) trial. Am Heart J. 2018;198:145–151.

- Velazquez EJ, Morrow DA, DeVore AD, et al. Angiotensin–neprilysin inhibition in acute decompensated heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(6):539–548.

- Whittington JW, Nolan K, Lewis N, et al. Pursuing the triple aim: the first 7 years. Milbank Q. 2015;93(2):263–300.

- Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff. (Millwood). 2008;27(3):759–769.

- CMS' Value-Based Programs: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2019 [cited 2019 October 27, 2019]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/Value-Based-Programs.html.

- Progress of Alternative Payment Models: 2019 Methodology and Results Repot. APM Mesaurement: Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network; 2019.

- Muhlestein D, Saunders R, McClellan M. Growth of ACOs and alternative payment models in 2017. Health Affairs Blog. 2017. Available from: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20170628.060719/full/

- Roberts M, Russell LB, Paltiel AD, et al.; ISPOR-SMDM Modeling Good Research Practices Task Force. Conceptualizing a model: a report of the ISPOR-SMDM Modeling Good Research Practices Task Force-2. Med Decis Making. 2012;32(5):678–689.

- Shared Savings Program Participation Options: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; [October 25, 2019]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/Downloads/ssp-aco-participation-options.pdf.

- Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Advanced Model Overview Fact Sheet: Model Year 3 (MY3): Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2019 [December 1, 2019]. Available from: https://innovation.cms.gov/Files/fact-sheet/bpciadvanced-my3-modeloverviewfs.pdf.

- Hospital Readmission Reduction Program: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; [October 25, 2019]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html.

- Atherton JJ, Bauersachs J, et al. UK NA-A, 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure; 2016.

- Novartis Data on File.

- U.S. Census QuickFacts U.S. Census Bureau; 2018. [October 25, 2019]. Available from: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045218.

- Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(16):e147–e239.

- Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics – 2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135(10):e146–e603.

- Fonarow GC, Stough WG, Abraham WT, et al. Characteristics, treatments, and outcomes of patients with preserved systolic function hospitalized for heart failure: a report from the OPTIMIZE-HF Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(8):768–777.

- Burnett H, Earley A, Voors AA, et al. Thirty years of evidence on the efficacy of drug treatments for chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a network meta-analysis. Circ Heart Fail. 2017;10(1):e003529.

- Inpatient Charge Data FY. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2016. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Medicare-Provider-Charge-Data/Inpatient.html

- Health Insurance Coverage. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics; 2017. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/releases/released201803.htm#1.

- Ginsburg PB. Wide variation in hospital and physician payment rates evidence of provider market power [Internet]. Washington (DC): Center for Studying Health System Change; 2010.

- Selden TM, Karaca Z, Keenan P, et al. The growing difference between public and private payment rates for inpatient hospital care. Health Aff. (Millwood). 2015;34(12):2147–2150.

- Stone DA, Dickensheets BA, Poisal JA. Comparison of Medicaid payments relative to Medicare using inpatient acute care claims from the Medicaid Program: Fiscal Year 2010 – Fiscal Year 2011. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(1):326–340.

- Zuckerman S. How much will Medicaid physician fees for primary care rise in 2013? Evidence from a 2012 survey of Medicaid physician fees; 2012.

- Storrow AB, Jenkins CA, Self WH, et al. The burden of acute heart failure on US emergency departments. JACC: Heart Fail. 2014;2(3):269–277.

- Health Care Spending and the Medicare Program: 2019. Medcare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC); 2019.

- McWilliams JM. Changes in Medicare shared savings program savings from 2013 to 2014. JAMA. 2016;316(16):1711–1713.

- McWilliams JM, Gilstrap LG, Stevenson DG, et al. Changes in postacute care in the Medicare Shared Savings Program. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(4):518–526.

- Maddox KEJ, Orav EJ, Zheng J, et al. Participation and dropout in the bundled payments for care improvement initiative. JAMA. 2018;319(2):191–193.

- Wadhera RK, Maddox KEJ, Wasfy JH, et al. Association of the hospital readmissions reduction program with mortality among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, and pneumonia. JAMA. 2018;320(24):2542–2552.

- Measuring Progress: Adoption of Alternative Payment Models in Commercial, Medicaid, Medicare Advantage, and Medicare Fee-for-Service Programs: Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network; 2018 [updated October 22, 2018]. Available from: http://hcp-lan.org/workproducts/apm-methodology-2018.pdf.

- Shared Savings Program Fast Facts – As of July 1, 2019: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2019 [cited 2019 December 1, 2019]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/Downloads/ssp-2019-fast-facts.pdf.

- Sood N, Huckfeldt PJ, Escarce JJ, et al. Medicare's bundled payment pilot for acute and postacute care: analysis and recommendations on where to begin. Health Aff. (Millwood). 2011;30(9):1708–1717.

- FY2019 IPPS Final Rule: Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program Supplemental Data File: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [cited Dec 14, 2018]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/FY2019-IPPS-Final-Rule-Home-Page-Items/FY2019-IPPS-Final-Rule-Data-Files.html.

- Dummit L, Marrufo G, Marshall J, et al. CMS bundled payments for care improvement initiative models 24: Year 5 Evaluation and Monitoring Annual Report Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2018.

- Shafrin J. Operating on commission: analyzing how physician financial incentives affect surgery rates. Health Econ. 2010;19(5):562–580.

- Ellis RP, McGuire TG. Provider behavior under prospective reimbursement: cost sharing and supply. J Health Econ. 1986;5(2):129–151.

- MaCurdy T, Shafrin J, Zheng D, et al. Optimal pay-for-performance scores: how to incentivize physicians to behave efficiently. Tech Rep. 2011. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Reports/Downloads/MaCurdy_Incentivize_Physicians_Optimal_P4P_Scores_Feb_2011.pdf

- Lichtenberg FR. Are the benefits of newer drugs worth their cost? Evidence from the 1996 MEPS. Health Aff. (Millwood). 2001;20(5):241–251.

- Zhang Y, Soumerai SB. Do newer prescription drugs pay for themselves? A reassessment of the evidence. Health Aff. (Millwood). 2007;26(3):880–886.

- Afendulis CC, Fendrick AM, Song Z, et al. The impact of global budgets on pharmaceutical spending and utilization: early experience from the alternative quality contract. INQUIRY. 2014;51:0046958014558716.

- Albert NM, Swindle JP, Buysman EK, et al. Lower hospitalization and healthcare costs with sacubitril/valsartan versus angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin-receptor blocker in a retrospective analysis of patients with heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(9):e011089.

- Kelsay E, Landers-Nelson D, Smith A, et al. The next wave of value generation in commercial ACOs Oliver Wyman Health 2018 [October 31, 2019]. Available from: https://health.oliverwyman.com/2018/08/committing_to_value.html.

- Sussell J, Bognar K, Schwartz TT, et al. Value-based payments and incentives to improve care: a case study of patients with type 2 diabetes in Medicare advantage. Value Health. 2017;20(8):1216–1220.

- Haas GJ, Pestritto VM, Abraham WT. Ultrafiltration for volume control in decompensated heart failure. Heart Fail Clin. 2008;4(4):519–534.

- Healthcare Spending and the Medicare Program. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission: Medicare Payment Advisory Commission; 2016.