Abstract

Objectives

To review the characteristics of patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) who attended primary and specialized care centers in Spain, and to analyze patients’ use of medical resources and direct medical costs of specialized care.

Methods

Records of patients with CKD admitted to primary and specialized healthcare centers in Spain between 2011 and 2017 from two national discharge databases were analyzed in a retrospective multicenter observational study. Records were classified into one-to-five CKD stages plus a 5b stage, indicating end-stage renal disease.

Results

Most of the patients registered in hospital settings were in stage 5. Registered secondary conditions included hypertensive chronic kidney, diabetes, anemia, hypercholesterolemia, and hypertension. The number of cases registered in primary care settings increased over time, whereas in specialized care centers incidence decreased; hospital incidence of CKD in 2017 was 10.72 per 10,000 persons. Mean in-hospital mortality was 5.90%, which remained stable during the study period. Mortality was associated with respiratory and heart failure. Mean length of hospital stay was 8.19 days, decreasing over the study period, whilst increasing with CKD progression. Mean annual direct medical cost of specialized care was €10,436 per patient. Complications of a transplant and bacterial infections were responsible for major increases in medical costs, that otherwise decreased over the study period.

Conclusions

The costs of specialized care decreased with the length of hospital stay reduction. Cardiovascular risk factors were crucial in in-hospital mortality. This study provides population-based data to assist decision-makers at the national level and to contribute to worldwide evaluations and disease surveillance.

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a major social and economic burden across the socioeconomic spectrum, with risk factors that are influenced by sex, ethnicity, and lifestyle. Its estimated global prevalence is between 11–13%, increasing worldwide, with the fastest growth taking place in low- and middle-income regionsCitation1–3. CKD is associated with a reduced quality-of-life and over 35 million global all-age disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) estimated in 2016Citation4. In terms of mortality, kidney diseases were the 12th cause of death worldwide in 2016, and the percentage of all deaths attributable to CKD globally was estimated to increase 33.7% between 2007 and 2017, when it caused over 1.2 million deathsCitation5,Citation6. In Spain, the prevalence of CKD remains around 15%, although in males it is estimated to reach 23%, and mortality rates are similar to global estimationsCitation7,Citation8.

The Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guideline statements defined CKD as abnormalities of kidney structure or function, present for more than 3 months, with implications for health and classified it based on cause, the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) category, and albuminuria category (CGA)Citation9. CKD has been associated to conditions such as vascular disease and diabetes that affect health outcomesCitation9.

Overall, this growing social burden is accompanied by great direct and indirect economic costs. In addition, evidence suggests a relation between costs and disease progression and with the presence of comorbid conditions that requires further evaluationCitation10.

Obtaining and evaluating real-world data is crucial to tackle the challenge that is CKD, providing evidence that reflects current practice, patients’ characteristics and needs, in order to improve understanding and treatment of chronic kidney diseaseCitation11.

This study aimed to provide an updated description of the characteristics of patients with CKD who attended primary and specialized care centers in Spain, to review CKD epidemiology within these settings, and to analyze patients’ use of healthcare resources and the associated direct medical costs.

Methods

Study design

A retrospective multicenter observational study was set to investigate the characteristics and use of healthcare resources of patients with CKD who attended primary and specialized healthcare centers in Spain between 2011 and 2017. Admission records were obtained from two national discharge databases managed by the Spanish Ministry of Health that gather medical information from 90% of public and private hospitals in Spain, and around 10% of primary care admissions, respectivelyCitation12,Citation13. Any healthcare visit was considered an admission (inpatient and outpatient) in each dataset. Primary care admissions are inherently outpatient and specialized care inpatient and outpatient admissions are discernible by the length of stay parameter, including both inpatient and outpatient care.

Data extraction

All records in which CKD was the principal diagnosis or admission motive were extracted from each database by means of the corresponding code. Primary care files are codified with the International Classification of Primary Care, Second edition (ICPC-2), thus, the code U99.01 corresponding to CKD was used to claim patient records in this setting. Specialized care diagnoses are codified with the International Classification of Diseases, ninth and tenth Revision, Clinical Modification codes (ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM). These categorize patients with CKD according to their GFR category into stages 1–5, with an additional code strictly indicating end-stage renal disease (ESRD) ()Citation14,Citation15. Patients in an unspecified CKD stage were codified separately. CKD stage was determined upon admission and could vary during the admission process after re-evaluation.

Table 1. Patient classification criteria according to ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes.

The selected patient files were obtained from the Spanish Ministry of Health previously recoded and anonymized in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. Primary care and hospital files were recoded independently, with no correlation of patient codes. This research did not involve human participants and there was no access to identifying information; in this context the Spanish legislation does not require patient consent and ethics committee approvalCitation16.

Study variables

Records of admissions from primary and specialized care contained raw information registered on admission, detailing the patient profile and admission details. Data gathered from primary care records included patients’ sex, age, date of admission, and admission motive; whereas the specialized care database registers additional information including type of admission (inpatient/outpatient, scheduled/urgent), type of discharge (including death), service that discharged the patient, length of hospital stay (LOHS), up to 20 secondary diagnoses registered during the admission, medical procedures, and cost of the admission.

Data analysis

Single-patient data obtained from the first admission registered per patient due to CKD was used to characterize the patient population in both primary and specialized care. Direct medical costs of specialized care were calculated using the cost per admission originally indicated in each admission file; such cost is estimated by using the standardized average expenses of admissions and medical procedures determined by the Spanish Ministry of HealthCitation17. This calculation included all expenses related to specialized care admissions: treatment (examination, medication, and surgery), nutrition, costs associated to personnel, medical equipment, and resources per groups of patients.

Frequencies and percentages are presented for dichotomous variables and mean and standard deviation were calculated for continuous variables. Hospital incidence was calculated as the proportion of patients admitted with CKD as the admission motive within the database. To assess the association of secondary conditions with in-hospital mortality, odd ratios (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) were used, calculated from frequency of diagnoses, using the group of patients non-deceased during the hospitalization as the reference group. Readmission was defined as a second admission within a 30-day period following discharge. Patients with an unspecified CKD stage were excluded from comparative analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Released 2011 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY) and Microsoft Excel Professional Plus 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA).

Results

Patient characteristics

Records from 125,674 patients registered with CKD were obtained from the primary care database, 48.24% of the patients were males with a mean age of 77.27 years (SD = 12.64).

Specialized care records were obtained from 24,389 patients, with 62.05% of patients being male. Mean age of the total patient population in this setting was 60.79 years (SD = 19.69) (). Overall, renal dialysis was registered in 23.47% of patients and renal transplants in 28.58%; 75.54% of those transplants were from a cadaver, 12.13% from a live related donor, and 6.40% from a live non-related donor.

Table 2. Characteristics of patients registered with chronic kidney disease in specialized care centers in Spain, number of admissions, and dialysis/renal transplants registered upon admission.

The secondary conditions that were registered in patients admitted with CKD are listed in . Hypertensive chronic kidney disease was the most commonly diagnosed condition, followed by diabetes, anemia, hypercholesterolemia, and hypertension. Patients in stage 5b (ESRD) displayed higher rates of secondary hyperparathyroidism of renal origin, bacterial infection, and complications derived from a transplanted kidney.

Table 3. Secondary conditions registered in more than 10% of admissions per chronic kidney disease stage in specialized care centers.

Hospital incidence and in-hospital mortality

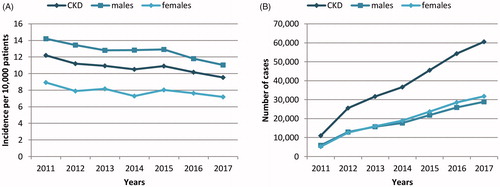

Hospital incidence of CKD was 10.72 per 10,000 patients in 2017, 11.04 for males and 7.18 for females, with a decreasing tendency over the study period (). Contrarily, the number of admissions due to CKD increased significantly over time in primary care centers ().

Figure 1. (A) Hospital incidence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and (B) annual number of admissions linked to CKD registered in primary care settings in Spain.

Mean in-hospital mortality was 5.90% during the study period. No significant differences in this rate were observed between 2011 and 2017. Mean in-hospital mortality was 6.30%, 4.54%, and 5.91% in patients in CKD stage 4, 5a, and 5 b, respectively. Overall mortality was greater in females than in males (4.40% vs 5.70%; p < 0.001).

The diagnosis of secondary conditions was evaluated as well in deceased patients. In-hospital mortality was predominantly associated with respiratory failure (18.20%, OR = 5.72; 95% CI = 4.78–6.85) and heart failure (18.10%, OR = 3.77; 95% CI = 3.16–4.49), followed by atrial fibrillation (23.54%, OR = 2.97; 95% CI = 2.55–3.46), disorders of fluid electrolyte and acid-base balance (23.54%, OR = 2.62; 95% CI = 2.25–3.06), chronic ischemic heart disease (12.34%, OR = 2.31; 95% CI = 1.89–2.83), chronic airway obstruction (11.61%, OR = 2.02; 95% CI = 1.64–2.48), and acute kidney failure (10.88%, OR = 1.56; 95% CI = 1.26–1.92).

Use of medical resources and costs

Referral for specialist treatment was only registered in 15.41% of primary care admissions, and only in 12.23% of those admissions patients were referred to nephrology and urology services. Nonetheless, 62.39% of the analyzed hospital admissions were into nephrology services and 11.31% into internal medicine services. Only 3.15% of specialized care admissions were outpatient admissions.

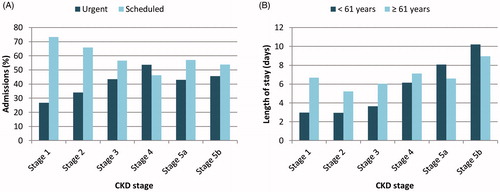

In early CKD stages, most hospital admissions were scheduled, with a higher percentage of urgent admissions found in advanced CKD stages (stage 1, 73.33%; stage 2, 65.92%; stage 3, 56.58%; stage 4, 46.18%; stage 5a, 56.98%; stage 5b, 53.82%) (). Mean length of hospital stay (LOHS) was 8.19 days (0–334), increasing with CKD progression, especially in patients under 61 years of age (p < 0.001, Stage 1 vs Stage 5b) (). Additionally, LOHS decreased significantly over time, from 8.85 days in 2011 to 7.20 days in 2017 (p < 0.001). Patients’ readmission rate was 13.07% over the study period.

Figure 2. (A) Percentage of urgent and scheduled hospital admissions per chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage and (B) mean length of hospital stay per age groups per chronic kidney disease stage. Stage 1, GFR 90–130 mL/min; stage 2, GFR 60–89 mL/min; stage 3, GFR 30–59 mL/min; stage 4, GFR 15–29 mL/min; stage 5a, GFR <15 mL/min without chronic dialysis; stage 5b, GFR <15 mL/min with chronic dialysis.

Kidney transplants and hemodialysis were the most common medical procedures registered for these patients, listed in 24.18% and 19.85% of all admissions, respectively, followed by various diagnosis techniques that were more common in early disease stages ().

Table 4. Medical procedures registered in more than 10% of admissions per chronic kidney disease stage.

Over the study period, 6,706 kidney transplants were registered, performed in 6,610 patients, mainly in stage 5. The mean age of these patients was 51.70 years and the mean length of hospital stay was 16.52 days.

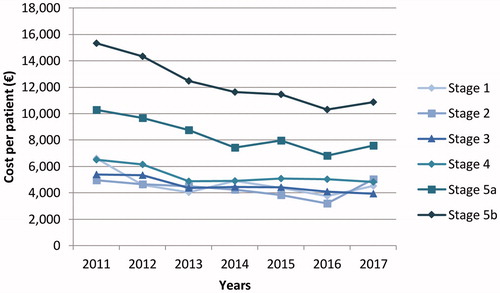

Mean annual direct medical cost of specialized care was €10,436 per patient, decreasing significantly over the study period from €11,739 in 2011 to €8,227 in 2017 (p < 0.001) due to the decrease in the costs incurred by patients in Stage 5 (). In addition, cost per patient increased significantly with CKD stage (p < 0.001, Stage 1 vs Stage 5b). Mean costs per patient over the study period were: €4,984 in stage 1, €4,535 in stage 2, €4,770 in stage 3, €5,887 in stage 4, €9,394 in stage 5a, and €14,329 in stage 5b, with a 1.23-fold increase between stages 3 and 4, a 1.57-fold increase between stages 4 and 5a, and a 1.44-fold increase between stages 5a and 5b.

Figure 3. Annual direct medical cost per patient per chronic kidney disease stage. Stage 1, GFR 90–130 mL/min; stage 2, GFR 60–89 mL/min; stage 3, GFR 30–59 mL/min; stage 4, GFR 15–29 mL/min; stage 5a, GFR <15 mL/min without chronic dialysis; stage 5b, GFR <15 mL/min with chronic dialysis.

On the other hand, the average cost per admission was €8,660, increasing to €10,213 in admissions to receive hemodialysis and to €23,049 in admissions in which a renal transplant was registered. Several secondary conditions were associated with raises in admission costs, with the highest costs associated to complications of a renal transplant ().

Table 5. Mean cost per admission due to chronic kidney disease per comorbid conditions.

Finally, the patient sample included in this study represented a total annual cost of €36.4 million in specialized care for the Spanish healthcare system, €28.6 million for dialysis and transplants alone.

Discussion

CKD is a major public health and social burden worldwide, with risk factors that include diabetes, systemic infections, autoimmune disorders, vascular disease, and environmental toxicity, although etiology is in many cases unknownCitation9,Citation18. The access to real-world hospitalization data allows the evaluation of current practice and contributes with crucial information to tackle major risk factors for CKD and to improve management and health outcomes.

Previous studies indicate a prevalence of CKD in Spain of around 15%, and a mortality rate that could be increasing, as measured in the global burden of disease studiesCitation7,Citation8. In the present study however, in-hospital mortality remained stable over the study period, which could be indicative of shifts in clinical practice rather than variations in disease mortality. The number of admissions linked to CKD in primary care settings increased over the study period, whereas hospital incidence, in specialized healthcare centers, decreased. An increasing tendency to treat milder symptoms of the disease in primary care must be considered when interpreting these data. Global meta-analyses indicate a higher prevalence of CKD stage 3, whilst most of the patients attended in hospital care were in stage 5Citation1. Indeed, the KDIGO guidelines recommend referral to specialist kidney care services when GFR is under 30 mL/min, namely stages 4 and 5Citation9. Another factor to be considered is the introduction of home hemodialysis as an alternative to the recurrent admissions required for in-hospital dialysis. This practice has increased progressively in many countries, yet, no records are available for Spain and its inclusion in standard practice appears distantCitation19. In this study, renal dialysis and transplants in hospital settings corresponded principally to patients in CKD stage 5. A small number of patients in early CKD stages registered renal replacement therapy, these cases corresponded to patients that changed CKD stage after an intervention or to other particular situations that could not be evaluated.

Secondary conditions corresponded to common CKD comorbidities. Hypertensive chronic kidney disease and diabetes were the most common conditions, presumably registered as the cause of CKD, followed by conditions with a renal origin, such as anemia or secondary hyperparathyroidismCitation20,Citation21. In particular, the Spanish population with CKD had presented an important prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors as described in the EPIRCE studyCitation22. Indeed, mortality in this study was associated with heart failure and several cardiovascular events. For the analysis per CKD stage, the patient classification process must be taken into account. CKD stage was assigned upon admission and stage often changed during the hospitalization process as status was re-evaluated.

On the other hand, disorders of fluid electrolyte and acid-base balance appeared relevant in patients in stages 3 and 4 and were associated with in-hospital mortality. Acidosis and hyperkalemia in CKD have been previously associated with increased morbidity and mortality, as current recommendations appeal for a rapid diagnosis and dietary and pharmacological treatment to manage the effects of these conditionsCitation23–25. The presence of these comorbid conditions may be distinctive in transplant and non-transplant patients; however, it could not be analyzed in this study.

Previous studies suggest that LOHS is highly dependent on the time elapsed to nephrology referral; while admissions with early referral had an average LOHS of 13.5 days, late referral registered LOHS of 25.3 daysCitation26. Late referral has also been associated with major hospitalization rates, higher mortality, and worsened health outcomesCitation27. The mean LOHS estimated herein, of 8.19 days, could be indicative of early referrals; however, this figure must be considered within a global context of decreasing LOHSCitation28.

In terms of costs, the decreasing tendency measured in the direct medical cost per patient over the study period could be the result of the improvement of disease management and the effort to reduce hospitalization times. The annual costs of specialized care, of €10,436 per patient, increased in association with complications of renal transplants and bacterial infections. Global evaluations show significant differences in cost estimations; a Italian study estimated a total medical cost of €4,508 per person on average (2016 Euros), €8,078 when summing non-medical and indirect costs, whereas costs per patient in the United States reached €17,052 ($20,162, 2012 USD)Citation10,Citation29. In terms of CKD stage, systematic reviews have identified increases in costs of 1.1–1.7-fold between CKD stage 3 and stages 4–5Citation30. Herein, progression between CKD stages 3 and 4 was associated to an increase in medical costs of 1.23-fold and 1.57-fold between stages 4 and 5a.

Efforts to reduce medical costs are centered on the improvement of disease management, which may reduce length of hospital stays, and early referral. Moreover, nephrologist-based multidisciplinary care has been associated with cost reduction as well as improved health outcomesCitation31. The effect of bacterial infections in increasing hospitalization costs must be considered in the revision of treatment protocols.

A number of limitations may have influence in the results of this study. This study included all the patients with CKD registered in the primary care and specialized care databases. The patient sample included does not aim to reflect the situation of CKD in the general Spanish population; a bias towards big hospitals that treat an important portion of severe cases cannot be discarded. Hospital incidence estimations are limited to the cases registered in the database, which must be taken into account when comparing with general evaluations. Similarly, data regarding renal transplants is subjected to this restriction, and transplants performed before the study period or in other healthcare centers were not included. Further studies will be required to evaluate the total burden associated to CKD, considering primary care costs, indirect costs, and non-medical costs.

Conclusions

The decreasing tendency measured in specialized care costs responds to the reduction of the length of hospital stay and disease management improvement. Cardiovascular risk factors were crucial in in-hospital mortality. Overall, this study provides new data, characterizing the Spanish population hospitalized due to CKD, to assist decision-makers at the national level and to contribute to worldwide evaluations with real-world population-based data.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of financial and other interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study is available from the Spanish Ministry of Health via the Unit of Health Care Information and Statistics (Spanish Institute of Health Information) for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data at https://www.mscbs.gob.es/estadEstudios/sanidadDatos/home.htm

References

- Hill NR, Fatoba ST, Oke JL, et al. Global prevalence of chronic kidney disease – a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0158765.

- Brück K, Stel VS, Gambaro G, et al. CKD prevalence varies across the European general population. JASN. 2016;27(7):2135–2147.

- Stanifer JW, Muiru A, Jafar TH, et al. Chronic kidney disease in low- and middle-income countries. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31(6):868–874.

- GBD 2016 DALYs and HALE Collaborators. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 333 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1260–1344.

- GBD 2017 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1736–1788.

- World Health Organization. Global health estimates 2016: deaths by cause, age, sex, by country and by region, 2000–2016. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

- Gorostidi M, Sánchez-Martínez M, Ruilope LM, et al. Chronic kidney disease in Spain: prevalence and impact of accumulation of cardiovascular risk factors. Nefrologia. 2018;38(6):606–615.

- Soriano JB, Rojas-Rueda D, Alonso J, et al. The burden of disease in Spain: results from the Global Burden of Disease 2016. Med Clin. 2018;151(5):171–190.

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3(1):1–150.

- Wang V, Vilme H, Maciejewski ML, et al. The economic burden of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease. Semin Nephrol. 2016;36(4):319–330.

- Katkade VB, Sanders KN, Zou KH. Real world data: an opportunity to supplement existing evidence for the use of long-established medicines in health care decision making. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2018;11:295–304.

- Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality. Hospitalization report – CMBD – discharge register: Report summary 2013 [Informe de hospitalización – CMBD – Registro de altas: Informe resumen 2013]. Madrid; 2015. Spanish.

- Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality. Primary Care clinical database. Data 2012. [Base de Datos Clínicos de Atención Primaria. Datos 2012]. Madrid; 2016. Spanish.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). International classification of diseases, ninth revision, clinical modification (ICD-9-CM). CDC; 2015 [accessed 2020 Feb 1]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd9cm.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). International classification of diseases, tenth revision, clinical modification (ICD-10-CM). CDC; 2020 [accessed 2020 Feb 1]. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd10cm.htm.

- Law 14/2007, 3rd July, on biomedical research (BOE, 4 July 2007). Rev Derecho Genoma Hum. 2007 Jan–Jun; (26):283–325.

- Spanish Ministry of Health. Weights of the GRDs of the National Health System. Spanish Ministry of Health; 2019 [accessed 2020 Feb 1]. https://www.mscbs.gob.es/en/estadEstudios/estadisticas/inforRecopilaciones/anaDesarrolloGDRanteriores.htm.

- Mills KT, Xu Y, Zhang W, et al. A systematic analysis of worldwide population-based data on the global burden of chronic kidney disease in 2010. Kidney Int. 2015;88(5):950–957.

- Pérez-Alba A, Barril-Cuadrado G, Castellano-Cerviño I, et al. Home haemodialysis in Spain. Nefrologia. 2015;35(1):1–5.

- Mikhail A, Brown C, Williams JA, et al. Renal association clinical practice guideline on Anaemia of Chronic Kidney Disease. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18(1):345.

- Liu P, Quinn RR, Karim ME, et al. Nephrology consultation and mortality in people with stage 4 chronic kidney disease: a population-based study. CMAJ. 2019;191(10):E274–82.

- Otero A, de Francisco A, Gayoso P, et al. Prevalence of chronic renal disease in Spain: results of the EPIRCE study. Nefrologia. 2010;30(1):78–86.

- Goraya N, Wesson DE. Management of the metabolic acidosis of chronic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2017;24(5):298–304.

- Nagami GT, Hamm LL. Regulation of acid-base balance in chronic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2017;24(5):274–279.

- Jun M, Jardine MJ, Perkovic V, Pilard Q, et al. Hyperkalemia and renin-angiotensin aldosterone system inhibitor therapy in chronic kidney disease: a general practice-based, observational study. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):e0213192.

- Chan MR, Dall AT, Fletcher KE, et al. Outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease referred late to nephrologists: a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2007;120(12):1063–1070.

- Campbell GA, Bolton WK. Referral and comanagement of the patient with CKD. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2011;18(6):420–427.

- Eurostat. Hospital discharges and length of stay statistics. Eurostat; 2020 [accessed 2020 Feb 7]. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Hospital_discharges_and_length_of_stay_statistics.

- Turchetti G, Bellelli S, Amato M, et al. The social cost of chronic kidney disease in Italy. Eur J Health Econ. 2017;18(7):847–858.

- Elshahat S, Cockwell P, Maxwell AP, et al. The impact of chronic kidney disease on developed countries from a health economics perspective: a systematic scoping review. PLoS One. 2020;15(3):e0230512.

- Lei CC, Lee PH, Hsu YC, Chang HY, et al. Educational intervention in CKD retards disease progression and reduces medical costs for patients with stage 5 CKD. Ren Fail. 2013;35(1):9–16.