Abstract

Aims

As the population in Japan is rapidly aging, the prevalence of dementia, particularly Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), is expected to increase, resulting in a growing need for caregivers. This study aims to quantify and compare the humanistic burden of caregivers of AD/dementia patients with caregivers of patients with other conditions in Japan.

Materials and methods

This cross-sectional study used data from the 2018 Japan National Health and Wellness Survey (NHWS). Outcome measures included the Short-Form 12-item Health Survey (SF-12) for health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL), EuroQol 5-dimension scale (EQ-5D) for health states utilities, impact of health on productivity and activity, and evaluation of depression and anxiety. Multivariate analysis was used to compare across groups, with adjustment for potential confounding effects.

Results

A total of 805 caregivers of AD/dementia patients, 1,099 other caregivers, and 27,137 non-caregivers were identified. Both AD/dementia caregivers and other caregivers had lower HRQoL and EQ-5D scores, higher total activity impairment, and more caregivers tended to experience anxiety than non-caregivers. There were no significant differences in the involvment in basic and instrumental activities of daily living (ADL) between AD/dementia caregivers and caregivers of other conditions. Notably, AD/dementia caregivers were more involved in making treatment decisions and finance management than other caregivers. Among AD/dementia caregivers caring for one patient, 395 patients lived in the community and 282 in an institution. AD/dementia caregivers whose patients lived in the community were more significantly involved in basic and instrumental ADL. Caregivers of patients with both AD/dementia and cancer had higher caregiving burden than caregivers of patients with either condition.

Conclusions

Caregivers of AD/dementia patients in Japan reportedly experienced significant humanistic burden which is associated with patients’ living arrangements and the presence of an additional chronic condition. Therefore, provision of effective care/support is essential to relieve the burden experienced by the caregivers.

Introduction

Dementia is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that is usually characterized by an initial gradual decline in the ability to remember new information, followed by deterioration of additional aspects of memory and other areas of cognition such as language, planning, and organizationCitation1. With the rapid aging of society, the number of people with dementia is likely to increase. Japan is projected to remain the world’s most aged population through 2050 (with 42.0% of the population over 65 years and above)Citation2. A study in 2018 highlighted that the mean prevalence of dementia in people aged 65 years and above was 15.8%Citation3. Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is the most predominant type of dementia, accounting for 65.8% of all casesCitation3,Citation4. A global study forecasted Japan as the country with the fastest growing prevalence of AD, where Japan could potentially see an annual growth rate of 4.0% of AD cases from 2016 to 2026Citation5.

An increasing burden is being placed on society as the population of people with dementia expands rapidly in Japan. The societal costs of dementia in 2014 was estimated at JPY 14.1 trillion (USD 112.7 billion) and is projected to reach JPY 24.3 trillion (USD 188.9 billion) by 2060Citation6. In addition to the significant economic strain, AD leads to emotional burden and psychological distress among family members and caregivers alongside the patient as AD patients require long-term careCitation7–9. A Japanese study reported that the disruptive behavioural, psychological, and functional symptoms of AD patients and caregiving activities increased the stress levels of AD caregiversCitation10. Another study in Japan showed that there was an incremental burden with greater AD patient severity and it is associated with poorer patient and caregiver health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL)Citation11. To improve living environments of people with dementia, Japan’s policies are shifting towards integrated community care systems to promote the development of dementia-friendly communitiesCitation12. Therefore, the likelihood that family members assume the role of a caregiver is strengthened by this shift towards community care.

While it is required to effectively distribute limited resources to establish a better care and welfare system, there is limited information on the comparison of the humanistic burden among caregivers of dementia, in particular for AD, caregivers of other chronic conditions, and non-caregivers in Japan. The humanistic burden is a holistic overview of the burden experienced by the caregivers with the consideration of the HRQoL, social and interpersonal, work productivity and activity impairment (WPAI), health and emotional aspects of measured health outcomes.

Dementia, in particular AD, is considered a terminal illness with similar negative connotations as other chronic conditions including cancerCitation13–15. Among chronic conditions, cancer is considered the most burdensome disease, placing significant burden on the caregivers, as cancer patients require long-term care and/or end-of-life decisions to be made by the caregivers as the disease progressesCitation16–18. This is especially important for Japan, given the number of people who develop cancer have also increased substantially in Japan due to the aging populationCitation19.

Thus, the primary objective of this study is to quantify and compare the humanistic burden among caregivers of patients with dementia or AD (AD/dementia) as well as caregivers of chronic conditions against non-caregivers. The secondary objective of this study is to evaluate the humanistic burden among caregivers of AD/dementia patients who lived in the community and who lived in an institution. As an exploratory objective, this study also assessed and compared the humanistic burden among caregivers of only AD/dementia, caregivers of only cancer patients, and caregivers of both AD/dementia and cancer patients. In this study, the caregivers of interest were informal caregivers (e.g. unpaid voluntary family members and friends).

Methods

Study design

This study utilized existing cross-sectional data from the 2018 Japan National Health and Wellness Survey (NHWS), an internet-based survey collecting self-reported patient characteristics and patient outcomes from adult respondents aged 18 or above. Respondents of the 2018 Japan NHWS were recruited from an existing web-based consumer panel maintained by Lightspeed Research (LSR). Panel members were recruited via opt-in email, e-newsletters, banner placements, and co-registration with other panel partners. All panellists provided informed consent. An age- and gender-specified sampling frame was imposed based on the governmental consensus data, to ensure the representativeness of NHWS respondents to the general adult population of Japan. The survey received Institutional Review Board approval by Pearl Pathways (IRB Study Number: 18-KANT-162) and Gifu Pharmaceutical University Institutional Review Board (2–13). All respondents provided informed consent prior to participation.

The NHWS included data on patient demographic and general health characteristics, patient health-related outcomes, as well as comprehensive information on a number of disease statuses, including self-reported experience, diagnosis of the conditions, and treatment received. The NHWS also included information on caregivers of patients of 20 pre-defined conditions, including AD (15.2% of all caregivers in the 2018 NHWS Japan database), autism (3.8%), bipolar disorder (2.3%), cancer (14.9%), Crohn’s disease (1.2%), chronic kidney disease on dialysis (3.3%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (1.1%), heart disease (3.7%), dementia (including AD) (31.1%), depression (8.0%), diabetes (Type I) (3.7%), epilepsy (2.4%), ITP (platelet disorder) (0.7%), macular degeneration (1.3%), multiple sclerosis (0.4%), muscular dystrophy (0.6%), osteoarthritis (2.3%), osteoporosis (8.2%), Parkinson's disease (5.4%), schizophrenia (4.6%), stroke (9.2%), and other conditions (9.0%).

Study population

All respondents were asked if they were currently caring for an adult relative with any of the above listed conditions. Based on the indications, the respondents were subsequently categorized into the following groups:

Caregivers of AD/dementia patients are defined as respondents who reported currently caring for an adult with AD and/or dementia.

Other caregivers are defined as respondents who reported currently caring for an adult relative with any of the other conditions than AD and dementia.

Non-caregivers are defined as respondents who were not caring for any adult relatives.

Among caregivers of AD/dementia patients, subgroup analysis was also conducted between caregivers and their patients with different living arrangements to understand how different living arrangements may impact the burden of caregivers. Only caregivers who are currently only caring for one adult relative were included in the subgroup analysis. Caregivers were categorized into two groups:

Caregivers who were caring for someone who lived on their own, in his/her home, or with the caregiver (in the community).

Caregivers who were caring for someone who lived in a specialist centre/hospital or in an assisted living centre/nursing home (an institution).

As further exploratory analysis to understand the humanistic burden of AD/dementia in comparison with other chronic conditions in Japan, caregivers of AD/dementia patients were further divided into the following subgroups:

Caregivers of AD/dementia without cancer are defined as caregivers of AD/dementia patients but not cancer patients.

Caregivers for both AD/dementia and cancer are defined as caregivers of patients diagnosed with both AD/dementia and cancer.

Caregivers in the two groups (1 and 2) were further compared with the caregivers of patients who have cancer but not AD/dementia (defined as caregivers of cancer without AD/dementia) to understand the incremental burden of caregiving experienced by the caregivers for both AD/dementia and cancer.

Measures, survey instruments, and outcome assessment

Demographic and health characteristics variables measured in this study included age, gender, marital status, level of education, household income, insurance type, employment status, number of children in the household, Charlson comorbidity indexCitation20–22, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, alcohol use, exercise frequency in past month, and currently taking steps to lose weight.

The involvement of caregivers in helping the patients with (i) basic activities of daily living (ADL), such as bathing or grooming, toileting, etc.; (ii) instrumental ADL (IADL), such as transportation, meal preparation, grocery shopping, etc.; (iii) making treatment decisions; and (iv) managing the finances were self-reported in a scale ranging from ‘I am not involved at all’ to ‘I am mainly responsible for these tasks’.

HRQoL was assessed using the mental component summary (MCS) and physical component summary (PCS) from the generic Short Form 12-item Health Survey version 2 (SF-12v2) instrumentCitation23. SF-12v2 comprises 12 questions that provide two summary scores: MCS and PCS scores, with higher scores indicating better quality-of-life.

Health state utilities were quantified by the EuroQoL 5-dimension scale (EQ-5D-5L), which provided a simple, generic measure of healthCitation24. The EQ-5D Index is derived from the EQ-5D domains of mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. Higher scores indicate better health status.

The work productivity and activity impairment (WPAI) questionnaire was used to measure the impact of health on employment-related and general activitiesCitation25. This six-item validated instrument consists of four metrics: absenteeism (the percentage of work time missed because of one’s health in the past 7 days), presenteeism (the percentage of impairment experienced because of one’s health while at work in the past 7 days), total work productivity impairment (an overall impairment estimate that is a combination of absenteeism and presenteeism), and activity impairment (the percentage of impairment in daily activities because of one’s health in the past 7 days). The four metrics are generated in the form of percentages, with higher percentage values indicating greater impairment. Only respondents who reported being full-time, part-time, or self-employed provided data for absenteeism, presenteeism, and total work productivity impairment. All respondents provided data for activity impairment.

Experience of depressive symptoms was evaluated by the self-reported Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), with a score ≥10 considered as experiencing depressionCitation26. Experience of anxiety disorders was evaluated by the self-reported General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), with a score ≥10 considered as experiencing anxietyCitation27.

Among caregivers, the impact of “taking care” were measured using a 24-item scale, the caregiver reaction assessment (CRA). The CRA is a multidimensional instrument that considers both negative and positive aspects of caregiving for any disease group regardless of mental or chronic diseaseCitation28–31. Responses were measured on a 5-point Likert scale from “Strongly disagree” to “Strongly agree”. Five aspects were measured in the CRA, including impact on health, caregivers’ esteem, impact on schedule, impact on finances, and lack of family support. The Japanese version of the CRA (CRA-J) was used for this studyCitation32.

Statistical analyses

Pairwise comparisons between caregivers of AD/dementia patients, other caregivers, and non-caregivers were conducted with respect to demographic and general health characteristics, and health outcomes using chi-square test for categorical variables and one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables.

Generalized linear models (GLMs) were used to compare HRQoL, WPAI, experience of depression and anxiety between caregivers of AD/dementia patients, other caregivers, and non-caregivers, adjusting for baseline characteristics. GLMs specifying normal distribution with identity link function were used for normally distributed outcomes including MCS, PCS, and EQ-5D index. GLMs specifying negative binomial distribution with log link function were used for discrete, count-like outcomes with skewed distribution (e.g. WPAI measures). Binomial distribution with logit link functions were used for binary outcomes, i.e. experience of depression and anxiety.

Among caregivers of AD/dementia patients, caregivers and patients with different living arrangements (in the community vs. in an institution) were compared in terms of their demographic and general health characteristics, health outcomes, and caregiver reactions using chi-square tests and ANOVA.

Similar pairwise comparisons and GLMs were also conducted between caregivers of AD/dementia without cancer patients, caregivers of cancer without AD/dementia patients, and caregivers of both AD/dementia and cancer patients.

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 25Citation33. p-values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All outcome variables in the main analysis were pre-determined and p-values were provided as an indication of the differences. No correction for multiple testing was conducted for this study.

Results

Participants

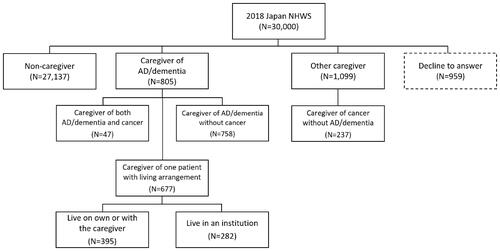

Among the 30,000 respondents to the 2018 Japan NHWS, a total of 805 caregivers provided care to AD/dementia patients. Another 1,099 caregivers were considered other caregivers, while 27,137 were non-caregivers (). Among 805 caregivers of AD/dementia patients, 677 were only caring for one patient and disclosed their living arrangement. Of the patients these caregivers were caring for, 395 lived on their own, in his/her home or with the caregiver, and the remaining 282 lived in a specialist centre or hospital or in an assisted living centre or nursing home.

Out of the total 805 caregivers of AD/dementia patients, 758 were caregivers of AD/dementia without cancer patients, whereas 47 were caregivers of both AD/dementia and cancer patients. There were also 237 caregivers of cancer without AD/dementia patients among the other caregivers.

Caregivers of AD/dementia vs. other caregivers vs. non-caregivers

More than two thirds of caregivers of AD/dementia patients were 50 years and older, significantly more than the non-caregivers. The proprtion of females among caregivers of AD/dementia patients were similar to that among the non-caregivers (51.9% vs. 49.5%), while there were more females among the other caregivers than non-caregivers (54.7% vs. 49.5%, p = 0.001). No significant differences were observed between these three groups in terms of level of education, employment status, and BMI. Caregivers of AD/dementia had the highest proportion of not having children in the household (86.3%), tended to have higher comorbid burden, drank alcohol more frequently (43.1% vs. 36.8% for at least 2–3 times a week, p < 0.001), and exercised more frequently (20.4% vs. 16.9% exercised at least 12 times, p = 0.010) than the non-caregivers ().

Table 1. Demographic and health characteristics among caregivers of AD/dementia, other caregivers, and non-caregivers.

Compared to the other caregivers, caregivers of AD/dementia tended to be older, more were married or living with a partner, more were without children in the household, consumed alcohol, and exercised more frequently.

Between these two groups of caregivers, the involvement of caregiving in different aspects of the tasks were compared. Although there were no significant differences in terms of the involvement in basic ADL (including bathing or grooming, toileting, feeding, transferring from bed to chair, or dealing with incontinence) and IADL (including transportation, meal preparation, grocery shopping, housework, medication management, or arranging for outside services), significantly more caregivers were more involved in making treatment decisions (including nursing home placement) and managing the finances for patients with AD/dementia, compared to caregivers of other conditions (Supplementary Table 1).

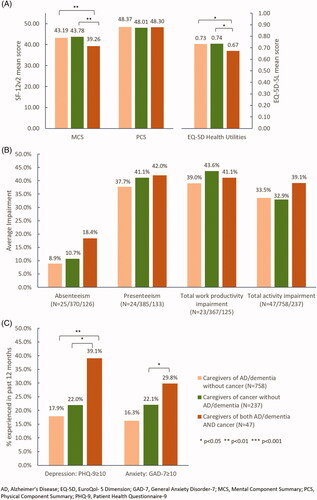

Baseline characteristics including age, gender, marital status, level of education, household income, insurance type, employment status, number of children in the household, CCI, BMI, smoking status, alcohol use, exercise frequency, and taking steps to lose weight were included in the GLM to make sure the differences in health outcomes after adjustment were only due to the different caregiver status. After adjusting for these potential confounders, compared to non-caregivers, both caregivers of AD/dementia patients and other caregivers experienced significantly lower HRQoL in terms of MCS, PCS, and EQ-5D scores (), increased WPAI in terms of increased absenteeism, presenteeism, total work productivity impairment and activity impairment (), as well as higher proportion of experience of depression and anxiety ().

Figure 2. HRQoL, WPAI, and depression and anxiety in non-caregivers, caregivers of AD/dementia patients, and other caregivers.

Compared to other caregivers, caregivers of AD/dementia patients had better PCS (50.17 vs. 49.13, p < 0.001) and EQ-5D index (0.79 vs. 0.77, p < 0.010) scores (). Although statistically significant, these HRQoL measures were similar numerically and were not deemed clinically meaningful. Caregivers of AD/dementia patients also had less total activity impairment (30.8% vs. 35.6%, p < 0.050) and a smaller proportion experienced anxiety as measured by GAD-7 (15.7% vs. 20.6%, p < 0.050) than other caregivers. The two caregiver groups were similar with respect to other health outcomes ().

Caregivers of AD/dementia with different living arrangements

Among 677 caregivers of AD/dementia patients caring for only one patient and who disclosed their living arrangements, 395 patients lived on their own, in his/her home or with the caregiver while the other 282 lived in a specialist centre/hospital or in an assisted living centre/nursing home. No significant differences in their baseline demographic and general health characteristics were observed between these two groups (results not shown). There were also no significant differences in the health outcomes between the two groups (Supplementary Table 2).

It was observed that the level of involvement in different types of caregiving tasks differ significantly between caregivers with different living arrangements. Compared to caregivers whose patients lived in an institution, caregivers whose patients lived in the community were significantly more involved in basic ADL (18.0% vs. 1.1% taking the main responsibility) and IADL (32.4% vs. 2.5% taking the main responsibility) (). There was no clear trend in caregivers’ involvement in making decisions around treatment and nursing home placement when the patients stayed in the community or in an institution.

Table 2. Involvement of caregivers in different types of caregiving tasks for caregivers of AD/dementia patients with different living arrangements.

No significant differences were observed between the two groups of caregivers with different living arrangements in all aspects of the CRA-J, except for schedule and health scores ().

Caregivers of AD/dementia and caregivers of cancer

To better understand the incremental burden of caregiving experienced by caregivers of AD/dementia, a chronic mental condition, as compared to a chronic physical condition, the burden of caregivers of cancer patients without AD/dementia were compared. The caregivers of AD/dementia patients were further divided into two groups – caregivers of AD/dementia without cancer, and caregivers of both AD/dementia and cancer. Among these three groups of caregivers, caregivers of AD/dementia without cancer tended to be older and had a higher proportion without children in the household than the other two groups (Supplementary Table 3). Caregivers of both AD/dementia and cancer tended to have higher comorbid burden than the other two groups.

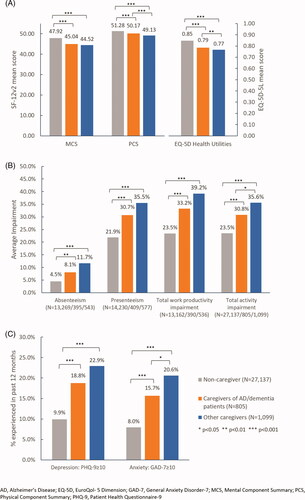

After adjusting for the same potential confounders, it was observed that caregivers of both AD/dementia and cancer patients had significantly lower MCS score (39.26 vs. 43.19 vs. 43.78, both p < 0.010) and EQ-5D index (0.67 vs. 0.73 vs. 0.74, both p < 0.050) than the other two caregiver groups (). However, there were no significant differences in the work and activity impairment across the three groups (). A significantly higher proportion of caregivers of both AD/dementia and cancer were observed to have experienced depressive symptoms (39.1% vs. 17.9% vs. 22.0%, p < 0.010/p < 0.050) and anxiety symptoms (29.8% vs. 16.3% vs. 22.1%, p < 0.050 comparing to caregivers of cancer without AD/dementia) compared to caregivers of AD/dementia without cancer and caregivers of cancer without AD/dementia, respectively ().

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to quantify the humanistic burden of caregivers of AD/dementia patients and compare with the humanistic burden of caring for patients with other conditions in Japan.

The findings from this study showed that the caregivers of AD/dementia, as well as caregivers of other conditions, had significantly lower HRQoL, which signifies greater burden among the caregivers compared to the non-caregivers. A Spanish study also showed that the HRQoL of caregivers of AD patients deteriorated over timeCitation34. Another study on caregivers of cancer patients in palliative settings also showed that the caregivers of cancer patients had lower quality-of-life scoresCitation35. Consistent with other studies, caregivers in general, regardless of patient conditions, (AD/dementia or other conditions) had higher work productivity impairmentCitation16,Citation36–39, with a higher proportion of caregivers having experienced depression and anxiety compared to non-caregiversCitation39–42. Interestingly, more caregivers of other conditions reported experiencing anxiety than caregivers of AD/dementia, however the reasons were not explored in this study. Further studies are warranted to explore this.

The study findings revealed that there were more female caregivers than non-caregivers, albeit the proportion of female AD/dementia caregivers were not significantly different from non-caregivers. Studies have shown that the reliance on females for caregiving were influenced by traditional culture, systems of patriarchy, and strict division of gender roles, where women stay at home and are assigned domestic rolesCitation43. Similarly, in Japan, the role of caregiving of elders typically falls onto females, either the spouse or an adult child, within the familyCitation44. Furthermore, caregivers of AD/dementia patients tended to be older than other caregivers. A 2019 survey done by the Japan health ministry showed that 60% of caregivers of people aged 65 years above who needed care and live with caregivers were in the same age rangeCitation45. Coupled with the finding that a higher proportion of AD/dementia caregivers do not have children, it is plausible that the burden of caregiving might instead fall onto the patient’s spouses, friends, or family members of similar age as the patient.

Several published studies have shown that decision-making capacity invariably deteriorates at some point along the dementia continuum, compromising patients autonomy in financial matters and medical decisionsCitation46–50. This is also evident in this study where a higher proportion of caregivers of AD/dementia were involved in managing treatment decisions and finances for the patients. Furthermore, in comparison to caregivers whose patients lived in an institution, caregivers whose patients are living on their own or with the caregivers were more involved in basic ADL and IADL. Studies reported that patients with AD/dementia are often unable to complete activities of daily life spanning from basic activities such as bathing or clothing to instrumental activities such as shopping or food preparation. This support to patients from caregivers regarding their basic personal care or activities of daily living is crucial for the maintenance and delivery of good quality care to AD/dementia patientsCitation51.

The findings also suggested that there is a potential association between the degree of care involvement and the humanistic burden experienced by caregivers to the patients, which is likely to be dependent on the patients’ living arrangements. The greater involvement of AD/dementia caregivers with patients living alone or with them could account for higher schedule and health scores as measured by CRA-J. The schedule and health scores of CRA-J measure the disruption in the caregivers’ daily schedule and their healthCitation28. A study reported that Japanese caregivers with primary caregiving activities had lower health outcomes, as measured by EQ-5D, in comparison to caregivers who were supported by secondary care or without caregiving activitiesCitation38. This implies there is an unmet need to provide stronger support to caregivers whose patients live in the community, to provide relief to the greater involvment in the patients’ basic ADL and IADL. With the shift towards the dementia-friendly communities for community long-term care of AD/dementia patients, including the enhancement of workforce for community-based services under the Long-Term Care Insurance (LTCI)Citation12,Citation52, the availability of care services, such as home-visit bathing, day-care services, under the LTCI could potentially provide respite for caregivers of AD/dementia patients living with themCitation53.

Importantly, this study explored the humanistic burden of caregiving among caregivers of AD/dementia against that of a physical chronic disease, such as cancer. Surprisingly, it was found that there was no significant differences in the HRQoL, WPAI as well as depression and anxiety experienced, suggesting that AD/dementia might have a similar negative impact to cancer. Limited studies suggested that burden of caregiving in both diseases is potentially affected by factors such as disease severity, patients’ physical comorbidities, and patients’ behaviour and psychological symptomsCitation14,Citation15,Citation54,Citation55.

Notably, caregivers of patients with both AD/dementia and cancer had higher comorbid burden and lower HRQoL, with a higher proportion experiencing depression and anxiety symptoms than caregivers of AD/dementia patients without cancer or caregivers of cancer patients without AD/dementia. These findings are consistent with previous studies on caregiver’s perspective whereby managing multiple chronic conditions in a patient has shown a significant impact on the caregiver’s quality-of-life. A Canadian study on management of multiple chronic conditions in the community reported that caregivers of patients with multiple chronic conditions felt overwhelmed and isolated by the complexity of the conditionsCitation56. Another study exploring caregivers’ experience in management of older patients with dementia and multiple chronic conditions also showed that caregivers of these patients experienced many changes in their caregiving journey resulting in increasing complexityCitation57. Previous research has implied that caregivers’ and patients’ support groups signifinicantly relieved feelings of depression and anxiety among the caregivers. Interestingly, these studies also reported that support groups had a small positive impact on relieving the burden of caregivingCitation58–60. Studies implied that substantive support such as financial or professional assistance could provide respite to caregiversCitation40,Citation59.

Taken altogether, this study provides a holistic view of the humanistic burden on the caregivers of AD/dementia patients compared to both the non-caregivers as well as caregivers of other diseases. Further sub-group analysis also showed that caregivers of patients with both AD/dementia and cancer had the highest burden and lowest quality-of-life compared to caregivers of patients with AD only or caregivers of patients with cancer only.

There are some limitations of this study. The data is cross-sectional, and no causal associations can be made. This study provided an initial indication of the differences in the humanistic burden between the caregivers and non-caregivers with existing large-scale cross-sectional data. Future studies with other appropriate study design and control group could be considered to conclude the burden of caregiving and the effect size. The NHWS is an online survey and hence respondents without internet access were not included in the study. In addition, although an age and gender specified sampling frame was imposed, the extent to which the study population and the caregivers were representative of the broader population is unclear. Furthermore, due to the self-reported nature of this study, caregivers may not be able to distinguish AD and dementia, making it impossible to distinguish caregivers of AD and caregivers of other forms of dementia. Although this study identified increased burden experienced by the groups of caregivers in Japan, it has not been established whether factors such as the disease severity, the engagement of caring services for community-based long-term care, economic costs, and medical insurance status of the patients could impact the burden of these caregivers, which warrant further investigation. In particular, incremental burden has been shown to be associated with increasing AD/dementia severity among caregivers but were not considered in this study due to the availability of data.

Conclusion

This study showed that caregivers of AD/dementia patients experienced lower HRQoL, increased WPAI, depression, and anxiety, comparable to the burden experienced by caregivers of other conditions. Additionally, this study also showed that caregivers of AD/dementia patients living with them are more involved in caring for the patients as compared to caregivers of AD/dementia patients not living with them. While the burden of caregiving for patients with either AD/dementia or cancer were comparable, caregivers of patients with both conditions had significantly higher burden. Thus, with increasing burden on the caregivers, it is essential to provide effective care/support to the caregivers in Japan, with the support not just limited to caregivers of AD patients only, but to caregivers of other diseases or caregivers of patients with multiple chronic conditions.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan.

Declaration of financial/other interests

Shinya Ohno and Motoaki Yoshino are employees of Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan. Yirong Chen is an employee of Kantar, Health Division, Singapore. Kantar received funding from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd for conducting the analysis and manuscript development. Hiroyuki Sakamaki has received honoraria from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Gifu Pharmaceutical University Institutional Review Board (IRB Study Number: 2–13) and Pearl Pathways (IRB Study Number: 18-KANT-162).

Previous presentations

The findings have not been published or presented previously.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (41.2 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank Amanda Woo at Kantar, Health Division, Singapore, for providing medical writing support and editorial support, which was funded by Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (http://www.ismpp.org/gpp3).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Kantar, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the corresponding author, SO, upon reasonable request and with permission of Kantar.

References

- Health (UK) NCC for M. DEMENTIA [Internet]. Dement. NICE-SCIE Guidel. Support. People Dement. Their Carers Health Soc. Care. British Psychological Society; 2007; [cited 2020 Dec 15]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK55480/.

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World population ageing, 2017 highlights. 2017.

- Montgomery W, Ueda K, Jorgensen M, et al. Epidemiology, associated burden, and current clinical practice for the diagnosis and management of Alzheimer’s disease in Japan. Clin Outcomes Res CEOR. 2018;10:13–28.

- Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement J Alzheimers Assoc. 2015;11:332–384.

- Global data. Japan will have the fastest growing prevalent cases of Alzheimer’s [Internet]. Clin. Trials Arena. 2017; [cited 2020 Jul 16]. Available from: https://www.clinicaltrialsarena.com/comment/japan-will-fastest-growing-prevalent-cases-alzheimers/.

- Sado M, Ninomiya A, Shikimoto R, et al. The estimated cost of dementia in Japan, the most aged society in the world. Khan HTA, editor. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0206508.

- Donaldson C, Burns A. Burden of Alzheimer’s disease: helping the patient and caregiver. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1999;12(1):21–28.

- Seidel D, Thyrian JR. Burden of caring for people with dementia – comparing family caregivers and professional caregivers. A descriptive study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2019;12:655–663.

- Koca E, Taşkapilioğlu Ö, Bakar M. Caregiver burden in different stages of Alzheimer’s Disease. Noro Psikiyatr Ars. 2017;54(1):82–86.

- Miyamoto Y, Tachimori H, Ito H. Formal caregiver burden in dementia: impact of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia and activities of daily living. Geriatr Nurs. 2010;31(4):246–253.

- Montgomery W, Goren A, Kahle-Wrobleski K, et al. Alzheimer’s disease severity and its association with patient and caregiver quality of life in Japan: results of a community-based survey. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):141.

- Japan Health Policy NOW – The New Orange Plan [Internet]; [cited 2020. Jul 16]. Available from: http://japanhpn.org/en/1-2/.

- End-of-Life Care for People with Dementia [Internet]. Natl. Inst. Aging; [cited 2020 Sep 14]. Available from: https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/end-life-care-people-dementia.

- Papastavrou E, Charalambous A, Tsangari H, et al. The burdensome and depressive experience of caring: what cancer, schizophrenia, and Alzheimer’s Disease caregivers have in common. Cancer Nurs. 2012;35(3):187–194.

- Haley WE, LaMonde LA, Han B, et al. Family caregiving in hospice: effects on psychological and health functioning among spousal caregivers of hospice patients with lung cancer or dementia. Hosp J. 2000;15(4):1–18.

- Ohno S, Chen Y, Sakamaki H, et al. Humanistic and economic burden among caregivers of patients with cancer in Japan. J Med Econ. 2019;23(1):17–27.

- Abdullah NN, Idris IB, Shamsuddin K, et al. Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL) of gastrointestinal cancer caregivers: the impact of caregiving. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2019;20(4):1191–1197.

- Borges EL, Franceschini J, Costa LHD, et al. Family caregiver burden: the burden of caring for lung cancer patients according to the cancer stage and patient quality of life. J Bras Pneumol. 2017;43(1):18–23.

- Cancer Incidence at All-Time High: 867,000 Cases Reported in 2014 [Internet]. nippon.com. 900; [cited 2020 Jul 27]. Available from: https://www.nippon.com/en/features/h00294/.

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383.

- Charlson ME, Charlson RE, Peterson JC, et al. The Charlson comorbidity index is adapted to predict costs of chronic disease in primary care patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(12):1234–1240.

- Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(6):676–682.

- Brazier JE, Roberts J. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-12. Med Care. 2004;42(9):851–859.

- EuroQol Group. EuroQol – a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208.

- Reilly MC, Gooch KL, Wong RL, et al. Validity, reliability and responsiveness of the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire in ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatol Oxf Engl. 2010;49(4):812–819.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613.

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097.

- Given CW, Given B, Stommel M, et al. The caregiver reaction assessment (CRA) for caregivers to persons with chronic physical and mental impairments. Res Nurs Health. 1992;15(4):271–283.

- Persson C, Wennman-Larsen A, Sundin K, et al. Assessing informal caregivers’ experiences: a qualitative and psychometric evaluation of the Caregiver Reaction Assessment Scale. Eur J Cancer Care. 2008;17(2):189–199.

- Malhotra R, Chan A, Malhotra C, et al. Validity and reliability of the Caregiver Reaction Assessment scale among primary informal caregivers for older persons in Singapore. Aging Ment Health. 2012;16(8):1004–1015.

- Stephan A, Mayer H, Guiteras AR, et al. Validity, reliability, and feasibility of the German version of the Caregiver Reaction Assessment scale (G-CRA): a validation study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25(10):1621–1628.

- Misawa T, Miyashita M, Kawa M, et al. Validity and reliability of the Japanese version of the Caregiver Reaction Assessment Scale (CRA-J) for community-dwelling cancer patients. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2009;26(5):334–340.

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk (NY): IBM Corp; 2017.

- Garzón-Maldonado FJ, Gutiérrez-Bedmar M, García-Casares N, et al. Health-related quality of life in caregivers of patients with Alzheimer disease. Neurol Engl Ed. 2017;32(8):508–515.

- Weitzner MA, McMillan SC, Jacobsen PB. Family caregiver quality of life: differences between curative and palliative cancer treatment settings. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;17(6):418–428.

- Fujihara S, Inoue A, Kubota K, et al. Caregiver burden and work productivity among Japanese working family caregivers of people with dementia. Intj Behav Med. 2019;26(2):125–135.

- Sruamsiri R, Mori Y, Mahlich J. Productivity loss of caregivers of schizophrenia patients: a cross-sectional survey in Japan. J Ment Health. 2018;27(6):583–587.

- Igarashi A, Fukuda A, Teng L, et al. Family caregiving in dementia and its impact on quality of life and economic burden in Japan-web based survey. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2020;8(1):1720068.

- Goren A, Montgomery W, Kahle-Wrobleski K, et al. Impact of caring for persons with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia on caregivers’ health outcomes: findings from a community based survey in Japan. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16(1):122.

- Chiao C-Y, Wu H-S, Hsiao C-Y. Caregiver burden for informal caregivers of patients with dementia: a systematic review. Int Nurs Rev. 2015;62(3):340–350.

- Candy B, Jones L, Drake R, et al. Interventions for supporting informal caregivers of patients in the terminal phase of a disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(6):CD007617.

- Pot AM, Deeg DJH, Dyck RV. Psychological well-being of informal caregivers of elderly people with dementia: changes over time. Aging Ment Health. 1997;1(3):261–268.

- Sharma N, Chakrabarti S, Grover S. Gender differences in caregiving among family – caregivers of people with mental illnesses. World J Psychiatry. 2016;6(1):7–17.

- Haya MAN, Ichikawa S, Wakabayashi H, et al. Family caregivers’ perspectives for the effect of social support on their care burden and quality of life: a mixed-method study in Rural and Sub-Urban Central Japan. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2019;247(3):197–207.

- Share of older people living with older caregivers hits record in Japan. Jpn Times Online [Internet]. 2020; [cited 2020 Jul 20]. Available from: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2020/07/20/national/older-people-caregivers-record-japan/.

- Okonkwo O, Griffith HR, Belue K, et al. Medical decision-making capacity in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2007;69(15):1528–1535.

- Hegde S, Ellajosyula R. Capacity issues and decision-making in dementia. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2016;19(Suppl 1):S34–S39.

- Alzheimer’s Society’s view on decision making [Internet]. Alzheimers Soc; [cited 2020 Jul 28]. Available from: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/about-us/policy-and-influencing/what-we-think/decision-making.

- Marson DC, Martin RC, Wadley V, et al. Clinical interview assessment of financial capacity in older adults with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(5):806–814.

- Dymek MP, Atchison P, Harrell L, et al. Competency to consent to medical treatment in cognitively impaired patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 2001;56(1):17–24.

- Brooker D. Dementia care mapping: a review of the research literature. Gerontologist. 2005;45(Spec No 1):11–18.

- Matsuda S, Yamamoto M. Long-term care insurance and integrated care for the aged in Japan. Int J Integr Care. 2001;1:e28.

- Hirakawa Y, Kuzuya M, Enoki H, et al. Caregiver burden among Japanese informal caregivers of cognitively impaired elderly in community settings. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2008;46(3):367–374.

- Costa-Requena G, Val ME, Cristòfol R. Caregiver burden in end-of-life care: advanced cancer and final stage of dementia. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13(3):583–589.

- Harding R, Gao W, Jackson D, et al. Comparative analysis of informal caregiver burden in advanced cancer, dementia, and acquired brain injury. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;50(4):445–452.

- Ploeg J, Matthew-Maich N, Fraser K, et al. Managing multiple chronic conditions in the community: a Canadian qualitative study of the experiences of older adults, family caregivers and healthcare providers. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):40.

- Ploeg J, Northwood M, Duggleby W, et al. Caregivers of older adults with dementia and multiple chronic conditions: exploring their experiences with significant changes. Dementia. 2019. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301219834423

- Schoenmakers B, Buntinx F, DeLepeleire J. Supporting the dementia family caregiver: the effect of home care intervention on general well-being. Aging Ment Health. 2010;14(1):44–56.

- Chu H, Yang C-Y, Liao Y-H, et al. the effects of a support group on dementia caregivers’ burden and depression. J Aging Health. 2011;23(2):228–241.

- Choo W-Y, Low W-Y, Karina R, et al. Social support and burden among caregivers of patients with dementia in Malaysia. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2003;15(1):23–29.