Abstract

Aims

The growing prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) worldwide has sparked the implementation of national policies to support the growing burden among caregivers of AD/dementia patients. This study aims to quantify and compare the burden of AD/dementia caregivers and evaluate how different living arrangements might impact health outcomes among caregivers in Japan, five European countries (5EU), and the United States (US).

Materials and methods

This is a cross-sectional study based on existing data from the 2018 National Health and Wellness Survey. Health outcome measures included health-related quality of life (HRQoL), health state utilities, work productivity and activity impairment (WPAI), and measurement of depression and anxiety amongst AD/dementia caregivers and non-caregivers. Pairwise comparisons between AD/dementia caregivers in Japan, 5EU, and the US were conducted. Multivariate analysis was used to compare across groups within each region, with adjustment for potential confounding effects.

Results

A higher proportion of caregivers of AD/dementia patients in Japan were 65 years or older as compared to 5EU and US. On the contrary, female caregivers were significantly higher in the US than Japan and 5EU. The HRQoL and health state utilities index scores amongst AD/dementia caregivers were highest in Japan and lowest in the US. Caregivers in Japan incurred the lowest WPAI among the three regions. The proportion of AD/dementia patients reportedly living in an institution was highest in Japan as compared to the US and EU. Notably, US caregivers whose patients lived in an institution experienced significantly less caregiving burden as compared to caregivers whose patients lived in the community.

Conclusions

The caregiving burden among AD/dementia caregivers was substantial across the three regions, with similarities and differences between the West and Japan. The lower caregiving burden in Japan was potentially associated with national policies supporting long-term healthcare and institutionalized nursing care facilities for AD/dementia patients.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is an acquired neurological condition and the most common form of dementia with large impact on activities of daily living (ADL)Citation1,Citation2. Dementia, including AD, is one of the leading causes of death worldwideCitation3. Without any available disease-modifying treatments or prevention strategies approved till date, dementia is an irreversible illnessCitation4–7. Current evidence indicated that high body mass index (BMI), high fasting plasma glucose, smoking, and a high intake of sugar-sweetened beverages attributed to the burden of dementia and could be targeted for preventionCitation4,Citation5. Dementia causes loss of independence, reduced quality of life to the patients, burden to the caregivers, as well as increased healthcare utilization and costCitation8,Citation9. Furthermore, dementia, including AD, is considered a terminal illness with similar negative connotationsCitation10, whereby there is an increasing patient reliance on the caregivers. More often, long-term care and/or end-of-life decisions would have to be managed by the caregivers on behalf of the AD/dementia patients as the disease progresses, potentially adding strain to the caregivers’ well-beingCitation10–12.

The number of individuals living with dementia was estimated to be around 45 million in 2016, almost doubled from 1990 estimatesCitation5,Citation13. As advances in medical science progressively contribute to extended life expectancy, leading to population aging and growth, this number is expected to triple by 2050Citation3,Citation4. The increasing number of dementia patients will continue to impose a significant burden to their families, informal caregivers, as well as the healthcare systemsCitation14. Caregivers of dementia patients often suffer from higher rates of burden, psychological morbidity, social isolation, physical ill-health, as well as financial hardshipCitation15.

In the United States (US), family members, friends, or neighbors are considered de-facto caregivers of older adults with dementia who live independently in the community, providing assistance to the ADL including medical/nursing activities such as wound care and medication managementCitation16,Citation17. Studies in the US showed that assuming medical/nursing tasks were associated with a more burdensome caregiving experienceCitation17. In Europe, caregivers to people with AD reportedly experienced moderate to high caregiver burden physically, psychologically, and financiallyCitation18,Citation19. In Japan, family caregivers of patients with AD or dementia reportedly experienced significantly higher burden and there was incremental burden associated with severity of AD patientsCitation20,Citation21. These studies collectively demonstrated that there is a worldwide burden of caring for AD/dementia patients.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and Alzheimer’s Disease International (ADI) jointly released a report in 2012 “Dementia: a public health priority” to aid governments and other stakeholders toward addressing the growing socio-economic impact of AD/dementia and promote it as a public health and social-care priorityCitation22. Japan, Europe, and the US were some of the nations to roll out national dementia plans. These plans overlap in their considerations for a range of issues for dementia including improving the quality of health care, social care and long-term support, and services for people living with dementia and their families as well as caregiversCitation23–25.

The Japanese national government announced a “Five-year Plan for Promotion of Measures Against Dementia (Orange Plan)” in 2012, with a further update of the plan in 2015Citation23. Care management is provided to individuals requiring home- and community-based care services under the long-term care insurance (LTCI) program until admission into institutional careCitation26. Furthermore, the initiative aims to establish medical institutions with trained dementia-support healthcare professionals to deliver timely and appropriate care to persons with AD/dementiaCitation23.

The European Alzheimer’s Initiative was established and endorsed by the European Parliament in early 2011, calling for EU member states to develop specific national policies for AD/dementiaCitation24. A common policy principle among European countries is to enhance resources for home- and community-based care services, allowing persons with AD/dementia to be cared for in their homes for as long as possible until the need for institutionalized careCitation27.

Similarly, the US government released the “National Alzheimer’s Project Act” (NAPA) in 2012 with a regular annual update of the planCitation25. The main goals of NAPA include the optimization and coordination of existing resources and care quality as well as the expansion of support for persons with AD/dementia and their familiesCitation25. Improving home- and community-based long-term care services and developing dementia-trained healthcare providers were some of the ongoing efforts to enhance dementia care quality and efficiency in the USCitation28.

Although burden of caregivers of AD patients has been studied in various regions, there has not been any study to compare the burden across the region. To provide a comparative landscape of the burden associated with care for patients with AD/dementia can be a first step to understanding how each region can better support these caregivers. Furthermore, despite the efforts to address AD/dementia, only 20%–50% of dementia cases in high-income regions were identified, with many AD/dementia individuals still delaying seeking treatment or supportCitation13,Citation29,Citation30, suggesting an unmet need in the policies for dementia. Henceforth, this study will focus on the burden in high-income regions such as Japan, the US, and Europe, with the focus on the top five countries with the highest nominal gross domestic product (GDP) – France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK as a collective region for Europe (5EU)Citation31.

The first primary objective of this study was to quantify and compare the burden of caregiving among caregivers of AD/dementia patients in these three regions. As a second primary objective, the burden of caregiving for AD/dementia patients was compared to that of non-caregivers in each region. The burden of caregiving measured in this study included health-related quality of life (HRQoL), work productivity and activity impairment (WPAI), depression, and anxiety. Further to the primary objective, the secondary objective was to understand how caregivers and patients with different living arrangements might impact the health outcomes of caregivers in these regions, respectively.

Methods

Study design

This study utilized existing data from the 2018 Japan, the US, and 5EU National Health and Wellness Survey (NHWS). The NHWS is a cross-sectional survey collecting self-reported patient characteristics and patient outcomes from adult respondents aged 18 or above in a total of 12 markets including Japan, the US, and the five EU countries (5EU: France, Germany, UK, Italy, and Spain). The NHWS questions were similar in all markets with slight modifications in each market. Respondents of the 2018 Japan, the US, and 5EU NHWS were recruited from an existing web-based consumer panel maintained by Lightspeed Research (LSR). Panel members were recruited via opt-in email, e-newsletters, banner placements, and co-registration with other panel partners. All panelists provided informed consent. Invitations to participate in the NHWS were sent out to the panelists. An age, gender, and race (only for the US) specified sampling frame was imposed in each market based on the governmental consensus data, to ensure representativeness to the general adult population of each market. Data were collected in 2018 between July to September in Japan, and between May to July in the US and 5EU. The surveys received Institutional Review Board approval by Pearl Pathways and Gifu Pharmaceutical University Institutional Review Board (2–13). All respondents provided informed consent prior to participation.

Respondents self-reported their demographic and general health characteristics, health-related outcomes, as well as comprehensive information on a number of disease status, including self-reported experience, diagnosis of the conditions, and treatment received in the NHWS. In NHWS, respondents also self-reported information on caregiving status of 22 pre-defined conditions including AD, autism, bipolar disorder, cancer, Crohn’s disease, chronic kidney disease on dialysis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart disease, dementia, depression, diabetes (Type I), epilepsy, ITP (platelet disorder), macular degeneration, multiple sclerosis, muscular dystrophy, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia, stroke, and other conditions.

Study population

In all three regions, respondents were asked if they currently were caring for an adult relative with any of the above-listed conditions. Respondents who reported currently caring for an adult with AD and/or dementia were classified as caregivers of AD/dementia patients. Respondents who were not caring for any adult relatives were classified as non-caregivers.

Among caregivers of AD/dementia patients, caregivers and their patients with different living arrangements were divided into subgroup. Among caregivers who were currently only caring for one adult relative and disclosed their living arrangement, caregivers were categorized into two groups: one whose patients that they are caring for lived on own, in his/her home, or with the caregiver (in the community); and another whose patients that they are caring for live in an institution (a specialist center or hospital, or in an assisted living center or nursing home).

Measures, survey instruments, and outcome assessment

In NHWS, all respondents answered questions on the demographic and personal health history, use of healthcare services, as well as validated instruments to measure the health outcomes. Selected groups of respondents also answered questions specific to their health conditions, as well as their caregiving status.

Demographic and health characteristics variables measured in this study included age, gender, marital status, level of education, household income, insurance type, employment status, Number of children in the household, Charlson comorbidity index (CCI)Citation32–34, BMI, smoking status, alcohol use, exercise frequency in past month, and currently taking steps to lose weight.

The involvement of caregivers in helping the patients with (i) basic ADL such as bathing or grooming, toileting, etc.; (ii) instrumental ADL (IADL) such as transportation, meal preparation, grocery shopping, etc.; (iii) making treatment decisions; and (iv) managing the finances were self-reported by the caregivers in a scale ranging from “I am not involved at all” to “I am mainly responsible for these tasks”.

HRQoL was assessed using the mental component summary (MCS) and physical component summary (PCS) from the generic Short Form 12-item Health Survey version 2 (SF-12v2) instrumentCitation35. The SF-12v2 comprises of 12 questions that cover eight health domains (physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role emotional, and mental health) and provide two summary scores: MCS and PCS scores, with higher scores indicating better quality of life. The SF-12v2 has been shown to have adequate psychometric validity in different populations in many countriesCitation36,Citation37.

Health state utilities were quantified by the EuroQoL 5-dimension scale (EQ-5D-5L), which provided a simple, generic measure of healthCitation38. The EQ-5D-5L has also demonstrated excellent psychometric properties across various populations and conditionsCitation39. The EQ-5D Index is derived from the EQ-5D domains of mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. Higher scores indicate better health status.

The WPAI questionnaire was used to measure the impact of health on employment-related and general activitiesCitation40. This six-item validated instrument consists of four metrics: absenteeism (the percentage of work time missed because of one’s health in the past 7 days), presenteeism (the percentage of impairment experienced because of one’s health while at work in the past 7 days), total work productivity impairment (an overall impairment estimate that is a combination of absenteeism and presenteeism), and activity impairment (the percentage of impairment in daily activities because of one’s health in the past 7 days). The four metrics are generated in the form of percentages, with higher percentage values indicating greater impairment. Only respondents who reported being full-time, part-time, or self-employed provided data for absenteeism, presenteeism, and total work productivity impairment. All respondents provided data for activity impairment.

Experience of depressive symptoms and anxiety disorders was evaluated by the self-reported Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)Citation41 and General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)Citation42, respectively. A respondent with PHQ-9 score ≥10 was considered as experience depression while a respondent with GAD-7 score ≥10 was considered as experience anxiety disorders. Both the PHQ-9 and the GAD-7 have proved to have adequate psychometric propertiesCitation43,Citation44.

Statistical analyses

Pairwise comparisons between caregivers of AD/dementia patients and non-caregivers were conducted with respect to demographic and general health characteristics, and health outcomes, using chi-square test for categorical variables and one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables in each region. Among caregivers of AD/dementia patients in all three regions, similar pairwise comparisons were also conducted to understand the differences between the regions.

Generalized linear models (GLMs) were used to compare HRQoL, WPAI, experience of depression and anxiety between caregivers of AD/dementia patients and non-caregivers, adjusting for baseline characteristics in three regions, respectively. Potential confounders included age, gender, marital status, level of education, household income, insurance type, employment status, number of children in the household, CCI, BMI, smoking status, alcohol use, exercise frequency, and taking steps to lose weight to make sure the differences in health outcomes after adjustment were only due to the different caregiver status. GLMs specifying normal distribution with identity link function were used for normally distributed outcomes including MCS, PCS, and EQ-5D index. GLMs specifying negative binomial distribution with log link function were used for discrete, count-like outcomes with skewed distribution (e.g. WPAI measures). Binomial distribution with logit link functions was used for binary outcomes, that is, experience of depression and anxiety.

Among caregivers within each region, caregivers and patients with different living arrangements were compared in terms of their demographic and general health characteristics and health outcomes using chi-square test and ANOVA.

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 25Citation45. p-Values of less than .05 were considered statistically significant. All outcome variables in the main analysis were pre-determined and p-values were provided as an indication of the differences. No correction for multiple testing was conducted for this study.

Results

Participants

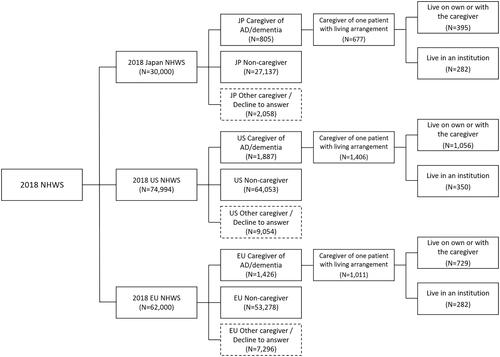

Among the 30,000 respondents to the 2018 Japan NHWS, a total of 805 caregivers provided care to AD/dementia patients, while 27,137 were non-caregivers. Of these 805 caregivers of AD/dementia patients, 677 were caring for one patient and disclosed their living arrangement − 395 patients lived in the community; 282 lived in an institution ().

In 2018, US NHWS, among total of 74,994 respondents, 1,887 were caregivers of AD/dementia patients and 64,053 were non-caregivers. Among the caregivers of AD/dementia patients, 1,406 caregivers were caring for one patient and disclosed their living arrangement (1,056 patients lived in the community while 350 lived in an institution) ().

In 2018, 5EU NHWS, there were 62,000 total responses with 1,426 caregivers of AD/dementia patients and 53,278 non-caregivers. Of 1,011 caregivers of AD/dementia patients who were caring for one patient and disclosed their living arrangement, 729 patients lived in the community while 282 lived in an institution ().

A highest proportion of caregivers of AD/dementia patients in Japan were elderlies 65 years or older (36.8%), followed by 5EU (19.9%) and US (15.4%). Significantly more caregivers in the US were females (61.5%), compared to Japan and 5EU (51.9% and 56.4%, p < .010/p = .003). There were significantly more caregivers in Japan with no children in the household (86.3% vs. 67.5% vs. 68.7%, both p < .001) and with CCI equals to 0 (78.9% vs. 64.7% vs. 70.5%, both p < .001) than US and 5EU. More than half of the caregivers (53.5%, 57.3%, and 57.2% in Japan, the US, and 5EU, respectively) in all three regions were currently employed. There were highest proportion of obese caregivers in the US although there were also highest proportion of caregivers who exercised 12 times or more in the US. Significantly more caregivers in Japan consumed alcohol at least 2–3 times a week ().

Table 1. Demographic and health characteristics among caregivers of AD/dementia patients in Japan, the US, and 5EU.

Comparisons of baseline characteristics of caregivers of AD/dementia patients and non-caregivers in each region are summarized in Supplementary Tables 1–3. With the exception of Japan, more caregivers of AD/dementia patients were younger than 65 years, employed, and have children as compared to non-caregivers in the US and 5EU. Across the regions, there were a greater proportion of AD/dementia caregivers who are smokers, consume alcohol at least 2–3 times per week and were overweight/obese as compared to non-caregivers.

Table 2. Involvement of caregiving in different types of caregiving tasks in caregivers of AD/dementia patients in Japan, the US, and 5EU.

Table 3. Involvement of caregiving in different types of caregiving tasks in caregivers of AD/dementia patients with different living arrangements in Japan, the US, and 5EU.

Caregivers’ responsibilities and health outcomes of caregivers of AD/dementia patients in Japan, the US, and 5EU

Across all three regions, the involvement of caregivers in basic ADL was similar with about half of the caregivers “not involved at all” (53.5%, 49.1%, and 48.7% in Japan, the US, and 5EU, respectively). About one-third of caregivers in Japan reported being “not involved at all” pertaining to tasks related to IADL, which was significantly higher than that in the US (16.1%) and in 5EU (24.3%). On the other hand, about one-third of caregivers in the US reported being “mainly responsible” for IADL tasks. More caregivers in Japan and the US were “mainly responsible for” making treatment and nursing home placement decisions and managing the finances, compared to that for caregivers in 5EU. On the other hand, more caregivers in Japan were “not involved at all” in these two tasks than caregivers in the US and 5EU ().

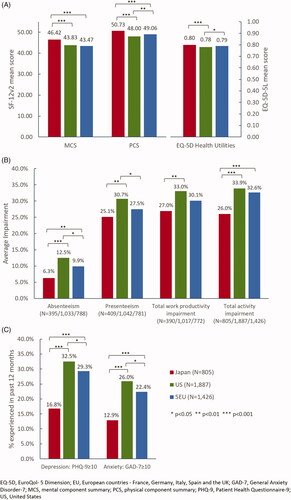

In terms of health outcomes, caregivers of AD/dementia patients in Japan had significantly higher MCS and PCS scores than caregivers in the US and 5EU (). Caregivers in 5EU also had better HRQoL in terms of PCS and EQ-5D index than caregivers in the US. Caregivers of AD/dementia patients in the US had the highest impairment in their work productivity, specifically they incurred the highest absenteeism, presenteeism, and total work productivity impairment among these three regions. Caregivers in Japan incurred the lowest among the three regions (). Caregivers in the US and 5EU had similar impairment in their total activity, which was significantly higher than that of caregivers in Japan. Remarkably, the proportion of caregivers who experienced depression measured by PHQ-9 score and who experienced anxiety measured by GAD-7 score in the US almost doubled that the proportion of caregivers in Japan, respectively. The proportions of depression and anxiety among caregivers of AD/dementia patients in 5EU were significantly less than that in the US and more than that in Japan ().

Figure 2. HRQoL, WPAI, and depression and anxiety among caregivers of AD/dementia patients in Japan, the US, and 5EU.

In each of the regions, after adjusting for potential confounders, caregivers of AD/dementia patients in Japan experienced significantly lower MCS, PCS, and EQ-5D index, increased absenteeism, presenteeism, total work productivity impairment, and total activity impairment, as well as higher proportion of depression and anxiety, compared to non-caregivers in Japan. Similarly, all health outcomes were significantly impaired among caregivers of AD/dementia in the US, compared to non-caregivers. In 5EU, however, there were no significant differences between caregivers of AD/dementia patients in terms of absenteeism; all other health outcomes were significantly impaired compared to non-caregivers (Supplementary Table 4).

Caregivers of AD/dementia with different living arrangements in Japan, the US, and 5EU

In Japan, there were 41.7% (282/677) caregivers whose patients lived in an institution. The proportion was relatively lower in the US (24.9%, 350/1,406) and 5EU (27.9%, 282/1,011). It was consistent across the regions that having the AD/dementia patients staying in an institution significantly reduced the involvement of their caregivers in their basic ADL and IADL (). In all regions, proportion of caregivers who were “mainly responsible for” tasks like bathing or grooming, toileting decreased from around 15%–20% to less than 5% when their patients stayed in an institution; proportion of caregivers who were “mainly responsible for” tasks like transportation, meal preparation decreased from 25%–37% to 2%–9% when their patients stayed in an institution. Caregivers’ involvement in making treatment decisions were similar between patients who stayed in the community and who stayed in an institution in Japan and the US, but significantly more caregivers were “not involved at all” in 5EU. No clear trend could be observed in the involvement in finances for caregivers with different living arrangements in all regions.

No significant differences in health outcomes including HRQoL, WPAI, and proportion of depression and anxiety were observed between caregivers with different living arrangements in Japan and 5EU (Supplementary Table 5). In contrary, in the US, caregivers whose patients lived in an institution experienced significantly higher MCS, PCS, and EQ-5D index scores and significantly lower impairment to their work productivity and activity, as well as smaller proportion of these caregivers’ experienced depression, compared to caregivers whose patients lived in the community.

Discussion

This study provided a novel comparative overview of the characteristics of caregivers and burden associated with providing care for patients with AD/dementia in Japan, the US, and 5EU. Gender differences were commonly observed where 57% to 81% of all caregivers of the elderly were female, and were wives or adult daughters in most casesCitation46. Contrary to the gender differences, caregivers of AD/dementia patients were not dominantly females, especially in Japan. It could be due to the higher prevalence of dementia among females, with age-standardized prevalence 1.17 times higher in females than in malesCitation4. Husbands of female patients took up the caregiving responsibilities. In Japan with high life expectancy and large elderly populationCitation47, around 60% of elderlies 65 years or older were cared by caregivers in the same age bracket, according to health ministry dataCitation48. As the population gets older in the US, 5EU, and even other countries, similar trend in terms of AD/dementia caregivers’ age and gender may be observed.

In terms of health outcomes, as expected, in each region, caregivers of AD/dementia incurred higher burden of caregiving with diminished HRQoL, more impairment in work productivity and activity, and higher proportion of depression and anxiety. This corroborates with many other studies. Comparisons across the regions suggested that generally caregivers in Japan had less burden in all aspects compared to caregivers in the US and 5EU. Remarkably, the proportion of depression and anxiety among caregivers in Japan was only about half that in the US. It has been shown in previous studies that although caregiving is a highly stressful and burdensome task, many caregivers reported positive aspects of caregiving which contributed to reducing the mental, physical and social issues of caregiversCitation49,Citation50. Studies implied that the level of caregiver strain perceived by caregivers in Japan and the US might be affected by variations in culture and social supports in each regionCitation51,Citation52. Inherent cultural differences in these regions, such as religion, spirituality, and caregiving appraisals attribute to how caregivers perceive caregiving tasks may influence the health outcomesCitation53–55. Japanese family traditions and values of filial piety and interdependence could explain for the lower depression/anxiety rates among Japanese caregivers as they were more likely to view caregiving as part of life’s trajectory, whereas, American caregivers might view caregiving as a disruption to their daily livesCitation56. It would be of interest for future studies to have further understanding of the cultural and societal values and guide policymaking to reduce the burden of caregivers in all regions.

Across the three regions, involvement of caregivers in ADL was similar with around half of the caregivers being “not involved at all”. The proportion of “not involved at all” was much higher than other assistance caregivers provided to the patients, including IADL, treatment decisions, and finances. Previous studies have focused on dependence on caregivers in terms of the basic ADL alone or basic ADL and IADL among patients and how that might impact caregiver burdenCitation57–59, the relatively less involvement of caregivers in basic ADL observed in this study suggested the significance of understanding and identifying ADL subdomains to better understand the burdenCitation60. The impairment of basic ADL has been relegated to the severity of AD/dementia, while IADL and financial capacity impairment were shown to occur at earlier stages of cognitive impairmentCitation61. Therefore, it is plausible that the degree of cognitive impairment of AD/dementia patients could have an impact on the degree of caregivers’ involvement on the ADL and IADL. Future studies investigating the impact of the stage of dementia are warranted.

In all three regions, when patients were institutionalized, caregivers’ involvement in basic ADL and IADL reduced significantly but the involvement in treatment decisions and finances remained somewhat similar. In addition, with a predicted increase in the number of patients with AD/dementia, it is expected that more patients will have to be cared in a family care setting rather than an institutional setting. Although nursing home placement helps caregivers to reduce their direct care burden, it does not always reduce caregiver burden especially mentally and financiallyCitation15,Citation62. Similar pattern was demonstrated in our study. It is crucial to shape policies and provide the support these family caregivers may need to reduce their burden of caregivingCitation63.

The overall lower burden of caregiving as well as the lower depression and anxiety rate reported by caregivers in Japan than in the US and 5EU could be associated with the proportion of AD/dementia patients reported to live in an institution. The proportion of patients reported by the caregivers to be living in an institution was the highest in Japan (42%) than in the US (24.9%) and 5EU (27.9%). This could be associated with the nation’s nursing care system and facilities that are well-established to deliver quality long-term care in JapanCitation64. Additionally, the recent social shift in the stigma surrounding institutionalized care in Japan, with less caregivers expressing conflicting feelings due to the traditional notion of “abandoning” familyCitation55,Citation64, together with financial support from the Japanese LTCICitation23,Citation64, could also attribute to the higher proportion of institutionalized AD/dementia patients. Interestingly, the findings in Supplementary Table 5 revealed that a similar quality of life was confirmed in both groups of caregivers regardless of the patients’ living arrangements in Japan. This suggests there is a similar degree of dementia care support provided by Japanese government to caregivers and their AD/dementia patients living in the community or in an institution.

In both Europe and the US, one of the objectives of their national dementia policies was centered around the engagement and involvement of caregivers in being part of the healthcare for AD/dementia patientsCitation25,Citation65. In Europe, the Balance of Care approach sought to provide affordable professional care services to informal caregivers and reduce the demand for institutionalized long-term care for cases where the AD/dementia individuals could be more appropriately supported in the communityCitation66–68. Similarly, in the US, the federal and state dementia policies have been aimed to encourage home- and community-based care settings for people with dementia through identification of caregivers’ needs and providing supportive servicesCitation25,Citation69. Moreover, the costs of institutional care were projected to be at least twice that of home- and community-based careCitation70,Citation71. These policies together with the higher costs incurred by institutional care potentially explain for the lower proportion of caregivers of AD/dementia living in the institution in the US and 5EU.

Notably, the caregivers of AD/dementia patients living in an institution in the US experienced a greater degree of burden relief when compared to caregivers of patients living with them (Supplementary Table 5). Studies revealed that American caregivers of AD/dementia patients living with them potentially face long wait times or limited access and coverage to respite paid-care support servicesCitation72–74. The benefits of institutionalized care settings, especially those associated with dementia-specific care units, include more timely response and access to professional care, treatment, and rehabilitation of patients with dementiaCitation74,Citation75, thereby possibly reducing the caregivers’ burden.

Japan is a rather homogenous nation with approximately 98% of the population JapaneseCitation76, whereas both the US and 5EU have a significantly diverse population of various ethnic groups which could influence the decision-making process of long-term care for people with AD/dementiaCitation53,Citation77,Citation78. Furthermore, Japan is the oldest nation in the world with a larger proportion of the population aged 65 years or olderCitation79, thereby actively driving national healthcare policies toward addressing issues of long-term care and/or end-of-life careCitation23. Inherent cultural and social differences among these three regions were not explicitly investigated in the current study.

The current study provided an overview of the similarities and differences in terms of caregiving burden in Japan, the US, and 5EU, wherein, a deeper dive into the specific policies that might impact the burden in each of the regions is warranted. Overall, AD/dementia caregivers in Japan experienced lower burden of caregiving than caregivers of AD/dementia patients in the US and 5EU. This could be associated with Japan’s preparedness to address the challenges of long-term care in consideration of its aging population as compared to the relatively younger population in the US and 5EUCitation79. This study also provided an initial indication of the differences between the caregivers and non-caregivers in three regions with existing large-scale cross-sectional data, and future studies with more appropriate study design and control group could be considered to conclude the burden of caregiving and the effect size. There are some limitations of this study. The data are cross-sectional, and no causal associations can be made. The NHWS is an online survey and hence respondents without internet access were not included in the study. In addition, although an age- and gender-specified sampling frame was imposed, the extent to which the study population and the caregivers were representative of the broader population is unclear. Although this study identified increased burden experienced by the groups of caregivers in Japan, the US, and 5EU, it has not been established what factors, including the state-specific social assistance policies for caregivers and the severity (stages of dementia) of the patients they are caring for, might impact the burden of these caregivers which warrant further investigation. The length the caregivers have been working as caregivers, which may impact the health outcomes due to caregiver burnout, were not captured in the survey but should be considered as an important covariate. Another limitation of this study is the comparison of caregivers’ burden in Europe based on the collective analyses of the five chosen nations due to the limited sample size for each nation in the 2018 NHWS. Although the dementia policies of 5EU generally aligned with the objectives established by Alzheimer Europe, each nation has slight variations in their national policies and strategies against AD/dementiaCitation24,Citation65 which were not explored in this study. Future studies would be warranted to better understand the impact of each nation’s healthcare system and social support for caregivers would affect the caregiving burden across Europe.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated the significant burden of caregiving among caregivers of AD/dementia patients in Japan, the US, and 5EU, and compared the burden across these regions. Across the regions, caregivers’ burden was considerably higher than non-caregivers with the burden in the US and 5EU higher than in Japan. National policies in the regions coincided in their strategies to address dementia-related issues within each region, for example, the lower caregiving burden in Japan could be associated with the national policies targeted at addressing the burden of long-term care in an aging Japan. There exist differences between the West and Japan which are specific to the needs of the region, potentially influencing the dependence of their caregivers toward different factors for caregiving support such as living arrangements for AD/dementia patients. These similarities and differences in caregiving burden provided valuable insights to inform future policy-shaping to better support the caregivers of AD/dementia patients in the future.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan.

Declaration of financial/other interests

S.O. and M.Y. are employees of Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan.

Y.C. is an employee of Kantar, Health Division, Singapore. Kantar received funding from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd for conducting the analysis and manuscript development.

H.S. has received honoraria from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan.

N.M. and K.T. declare no conflict of interest.

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

S.O., Y.C., H.S., N.M., M.Y., and K.T. conceptualized the study. S.O. and Y.C. conducted the statistical analysis. H.S., N.M., M.Y., and K.T. advised and reviewed the analysis. All authors wrote and reviewed the final manuscript.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by Pearl Pathways (IRB Study Number: 18-KANT-162) and Gifu Pharmaceutical University Institutional Review Board (IRB Study Number: 2–13).

Previous presentations

The findings have not been published or presented previously.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (80.8 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank Amanda Woo at Kantar, Health Division, Singapore, for providing medical writing support and editorial support, which was funded by Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (http://www.ismpp.org/gpp3).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Kantar, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are, however, available from the corresponding author, S.O., upon reasonable request and with permission of Kantar.

References

- Hodson R. Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2018;559(7715):S1.

- Lane CA, Hardy J, Schott JM. Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurol. 2018;25(1):59–70.

- Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, et al. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Lond Engl. 2016;388(10053):1459–1544.

- Collaborators GBD 2016 Dementia. Global, regional, and national burden of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18:88.

- Tipton PW, Graff-Radford NR. Prevention of late‐life dementia: what works and what does not. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2018;128(5):310–316.

- Chiao C-Y, Wu H-S, Hsiao C-Y. Caregiver burden for informal caregivers of patients with dementia: a systematic review. Int Nurs Rev. 2015;62(3):340–350.

- Yiannopoulou KG, Papageorgiou SG. Current and future treatments in Alzheimer disease: an update. J Cent Nerv Syst Dis. 2020;12:1179573520907397.

- Etters L, Goodall D, Harrison BE. Caregiver burden among dementia patient caregivers: a review of the literature. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2008;20(8):423–428.

- Fiest KM, Jetté N, Roberts JI, et al. The prevalence and incidence of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Neurol Sci. 2016;43(S1):S3–S50.

- End-of-Life Care for People with Dementia[Internet]. National Institute on Aging. [cited 2020 Sep 14]. Available from: https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/end-life-care-people-dementia

- Papastavrou E, Charalambous A, Tsangari H, et al. The burdensome and depressive experience of caring: what cancer, schizophrenia, and Alzheimer’s disease caregivers have in common. Cancer Nurs. 2012;35(3):187–194.

- Haley WE, LaMonde LA, Han B, et al. Family caregiving in hospice: effects on psychological and health functioning among spousal caregivers of hospice patients with lung cancer or dementia. Hosp J. 2000;15(4):1–18.

- World Alzheimer Report 2015. The global impact of dementia. London: Alzheimer’s Disease International; 2015.

- Burns A. The burden of Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Neuropsychopharm. 2000;3(7):S31–S38.

- Brodaty H, Donkin M. Family caregivers of people with dementia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2009;11(2):217–228.

- 2018 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer’s Association; 2018. [Internet]. Available from: https://www.alz.org/media/HomeOffice/Facts%20and%20Figures/facts-and-figures.pdf

- Lee M, Ryoo JH, Campbell C, et al. Exploring the challenges of medical/nursing tasks in home care experienced by caregivers of older adults with dementia: an integrative review. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28(23–24):4177–4189.

- Farina N, Page TE, Daley S, et al. Factors associated with the quality of life of family carers of people with dementia: a systematic review. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(5):572–581.

- Svendsboe E, Terum T, Testad I, et al. Caregiver burden in family carers of people with dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31(9):1075–1083.

- Goren A, Montgomery W, Kahle-Wrobleski K, et al. Impact of caring for persons with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia on caregivers’ health outcomes: findings from a community based survey in Japan. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16(1):122.

- Montgomery W, Goren A, Kahle-Wrobleski K, et al. Alzheimer’s disease severity and its association with patient and caregiver quality of life in Japan: results of a community-based survey. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):141.

- World Health Organization and Alzheimer’s Disease International. Dementia: a public health priority[Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012 [cited 2020 Sep 17]. p. 112. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/dementia_report_2012/en/

- Japan Health Policy NOW – The New Orange Plan [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 16]. Available from: http://japanhpn.org/en/1-2/

- Alzheimer’s Disease International. Action in Europe | Alzheimer’s Disease International [Internet]. [cited 2020 Sep 17]. Available from: https://www.alz.co.uk/plans/action-in-europe

- National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Disease [Internet]. Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2015 [cited 2020 Sep 17]. Available from: https://aspe.hhs.gov/national-plan-address-alzheimers-disease

- Nakanishi M, Nakashima T. Features of the Japanese national dementia strategy in comparison with international dementia policies: how should a national dementia policy interact with the public health- and social-care systems? Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(4):468–476.e3.

- Pavolini E, Ranci C. Reforms in long-term care policies in Europe: introduction. In: Ranci C, Pavolini E, editors. Reforms in long-term care policies in Europe: investigating institutional change and social impacts. New York (NY): Springer; 2013. p. 3–22.

- National Plans to Address Alzheimer’s Disease [Internet]. ASPE; 2015 [cited 2021 Jan 4]. Available from: https://aspe.hhs.gov/national-plans-address-alzheimers-disease

- Alzheimer’s Disease International. World Alzheimer Report 2019: Attitudes to dementia | Alzheimer’s Disease International; 2019 [Internet] [cited 2020 Sep 17]. Available from: https://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2019.pdf

- Prince MJ, Bryce Renata, Ferri C. World Alzheimer Report 2011: the benefits of early diagnosis and intervention. Alzheimer’s Disease International (ADI); 2011 [Internet]. [cited 2020 Sep 17]; p. 72. Available from: https://www.alz.co.uk/research/world-report-2011

- Prince MJ, Wimo A, Guerchet M, et al. World Economic Outlook Database, October 2019. [Internet]. Alzheimer’s Disease International (ADI), London; 2015 [cited 2020 Sep 17]. Available from: https://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2015.pdf

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383.

- Charlson ME, Charlson RE, Peterson JC, et al. The Charlson comorbidity index is adapted to predict costs of chronic disease in primary care patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(12):1234–1240.

- Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(6):676–682.

- Brazier JE, Roberts J. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-12. Med Care. 2004;42(9):851–859.

- Shah RM, Banahan BF, Holmes ER, et al. An evaluation of the psychometric properties of the sf-12v2 health survey among adults with hemophilia. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16(1):229.

- Fukuhara S, Ware JE, Kosinski M, et al. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity of the Japanese SF-36 Health Survey. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(11):1045–1053.

- EuroQol Group. EuroQol - a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208.

- Feng Y-S, Kohlmann T, Janssen MF, et al. Psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-5L: a systematic review of the literature. Qual Life Res. 2020. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-020-02688-y

- Reilly MC, Gooch KL, Wong RL, et al. Validity, reliability and responsiveness of the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire in ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatol Oxf Engl. 2010;49(4):812–819.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613.

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097.

- Kim YE, Lee B. The psychometric properties of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 in a sample of Korean university students. Psychiatry Investig. 2019;16(12):904–910.

- Johnson SU, Ulvenes PG, Øktedalen T, et al. Psychometric properties of the General Anxiety Disorder 7-Item (GAD-7) scale in a heterogeneous psychiatric sample. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1713.

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk (NY): IBM Corp; 2017.

- Sharma N, Chakrabarti S, Grover S. Gender differences in caregiving among family - caregivers of people with mental illnesses. World J Psychiatry. 2016;6(1):7–17.

- Ho JY, Hendi AS. Recent trends in life expectancy across high income countries: retrospective observational study. BMJ. 2018;362:k2562.

- Share of older people living with older caregivers hits record in Japan. Japan Times Online; 2020 Jul 20 [Internet]. Available from: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2020/07/20/national/older-people-caregivers-record-japan/

- Abdollahpour I, Nedjat S, Salimi Y. Positive aspects of caregiving and caregiver burden: a study of caregivers of patients with dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2018;31(1):34–38.

- Cohen CA, Colantonio A, Vernich L. Positive aspects of caregiving: rounding out the caregiver experience. Int J Geriat Psychiatry. 2002;17(2):184–188.

- Tanji H, Koyama S, Wada M, et al. Comparison of caregiver strain in Parkinson’s disease between Yamagata, Japan, and Maryland, The United States. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2013;19(6):628–633.

- Wallhagen MI, Yamamoto-Mitani N. The meaning of family caregiving in Japan and the United States: a qualitative comparative study. J Transcult Nurs. 2006;17(1):65–73.

- Dilworth-Anderson P, Williams IC, Gibson BE. Issues of race, ethnicity, and culture in caregiving research: a 20-year review (1980–2000). Gerontologist. 2002;42(2):237–272.

- Adams B, Aranda MP, Kemp B, et al. Ethnic and gender differences in distress among Anglo American, African American, Japanese American, and Mexican American spousal caregivers of persons with dementia. J Clin Geropsychology. 2002;8(4):279–301.

- McCormick WC, Ohata CY, Uomoto J, et al. Similarities and differences in attitudes toward long-term care between Japanese Americans and Caucasian Americans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(6):1149–1155.

- Mokuau N, Tomioka M. Caregiving and older Japanese adults: lessons learned from the periodical literature. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2010;53(2):117–136.

- Kawaharada R, Sugimoto T, Matsuda N, et al. Impact of loss of independence in basic activities of daily living on caregiver burden in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a retrospective cohort study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2019;19(12):1243–1247.

- Kang HS, Myung W, Na DL, et al. Factors associated with caregiver burden in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Psychiatry Investig. 2014;11(2):152–159.

- Suzuki Y, Nagasawa A, Mochizuki H, et al. Effects on activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living independence in patients with Alzheimer’s disease when the main nursing caregiver consciously provides only minimal nursing care. J Phys Ther Sci. 2019;31(4):398–402.

- Reed C, Belger M, Vellas B, et al. Identifying factors of activities of daily living important for cost and caregiver outcomes in Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2016;28(2):247–259.

- Marshall GA, Amariglio RE, Sperling RA, et al. Activities of daily living: where do they fit in the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease? Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2012;2(5):483–491.

- Schulz R, Belle SH, Czaja SJ, et al. Long-term care placement of dementia patients and caregiver health and well-being. JAMA. 2004;292(8):961–967.

- Igarashi A, Fukuda A, Teng L, et al. Family caregiving in dementia and its impact on quality of life and economic burden in Japan-web based survey. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2020;8(1):1720068.

- Tamiya N, Noguchi H, Nishi A, et al. Population ageing and wellbeing: lessons from Japan’s long-term care insurance policy. Lancet. 2011;378(9797):1183–1192.

- Alzheimer Europe. Our work - strategic plan (2016–2020) [Internet]; 2016 [cited 2020 Sep 18]. Available from: https://www.alzheimer-europe.org/Alzheimer-Europe/Our-work/Strategic-Plan-2016-2020

- Tucker S, Sutcliffe C, Bowns I, et al. Improving the mix of institutional and community care for older people with dementia: an application of the balance of care approach in eight European countries. Aging Ment Health. 2016;20(12):1327–1338.

- Improving health services for European citizens with dementia: development of best practice strategies for the transition from ambulatory to institutional long-term care facilities | RIGHTTIMEPLACECARE Project | FP7 | CORDIS | European Commission [Internet]. [cited 2020 Sep 21]. Available from: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/242153

- Moise P, Schwarzinger M, Um M-Y, et al. Dementia care in 9 OECD countries: a comparative analysis [Internet]. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; 2004. p. 109. [cited 2020 Sep 19]. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/33661491.pdf

- National Quality Forum. NQF: quality in home and community-based services to support community living: addressing gaps in performance measurement [Internet]; 2016 [cited 2020 Sep 21]. Available from: https://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2016/09/Quality_in_Home_and_Community-Based_Services_to_Support_Community_Living__Addressing_Gaps_in_Performance_Measurement.aspx

- Genworth. Genworth Cost of Care Survey. | Median cost data tables. Genworth.com [Internet]; 2019 [cited 2020 Sep 21]. Available from: https://pro.genworth.com/riiproweb/productinfo/pdf/282102.pdf

- Wübker A, Zwakhalen SMG, Challis D, et al. Costs of care for people with dementia just before and after nursing home placement: primary data from eight European countries. Eur J Health Econ. 2015;16(7):689–707.

- Black BS, Johnston D, Rabins PV, et al. Unmet needs of community-residing persons with dementia and their informal caregivers: findings from the maximizing independence at home study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(12):2087–2095.

- Leggett A, Connell C, Dubin L, et al. Dementia care across a tertiary care health system: what exists now and what needs to change. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(10):1307–1312.e1.

- Lepore M, Ferrell A, Wiener JM. Living arrangements of people with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: implications for services and supports. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services; 2017. p. 23. Available from: https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/living-arrangements-people-alzheimers-disease-and-related-dementias-implications-services-and-supports

- Cadigan RO, Grabowski DC, Givens JL, et al. The quality of advanced dementia care in the nursing home: the role of special care units. Med Care. 2012;50(10):856–862.

- Japan Population 2020 (Demographics, Maps, Graphs) [Internet]. [cited 2020 Sep 21]. Available from: https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/japan-population

- Verbeek H, Meyer G, Challis D, et al. Inter-country exploration of factors associated with admission to long-term institutional dementia care: evidence from the RightTimePlaceCare study. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71(6):1338–1350.

- Hikoyeda N, Miyawaki CE, Yeo G. Handbook of Geriatric Care Management. Burlington (MA): Jones & Bartlett Publishers; 2015. Chapter 6. Ethnic and cultural considerations in care management; p. 120–145.

- Population Reference Bureau. Which country has the oldest population [Internet]; 2020 [cited 2020 Sep 21]. Available from: https://www.prb.org/countries-with-the-oldest-populations/