Abstract

Objective

This study evaluated infection-related hospitalization risk and cost in tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi)-experienced and targeted DMARD (tDMARD) naïve rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients that were treated with abatacept, TNFi, or other non-TNFi.

Methods

This retrospective study used 100% Medicare Fee-for-Service claims to identify patients ≥65 age, diagnosed with RA, and were either 1) TNFi-experienced, who switched from a TNFi to another tDMARD (subsequent tDMARD claim served as index), or 2) tDMARD naïve (first therapy claim served as index), who initiated either abatacept, TNFi, or non-TNFi as their first tDMARD, between 2010 and 2017. Follow-up ended at the date of disenrollment, death, end of study period, or end of index treatment, whichever occurred first. Infection-related hospitalizations included pneumonia, bacterial respiratory, sepsis, skin and soft tissue, joint or genitourinary infections. A Cox proportional hazard model and two part generalized linear model were developed to estimate adjusted infection-related hospitalization risk and costs. Costs were normalized to per-patient-per-month (PPPM) and inflated to 2019 US$.

Results

The infection-related hospitalizations rate was lower during follow-up than during baseline periods for abatacept users, but was reversed for both TNFi and other non-TNFi users in both TNFi-experience and tDMARD naïve (p value < .001 based on Breslow-Day test for homogeneity of odds ratios). Infection-related hospitalization PPPM cost was significantly lower in abatacept treated patients compared to TNFi (TNFi-experienced: by $74; tDMARD naïve: $42) and other non-TNFi (TNFi-experienced: by $68; tDMARD naïve: $60). The adjusted infection-related hospitalization risk was significantly higher for RA patients treated with TNFi (TNFi-experienced HR: 1.48; 95% CI: 1.26–1.75, p < .0001; tDMARD naïve HR:1.59; 95% CI: 1.43–1.77, p < .0001) and other non-TNFi (TNFi-experienced HR:1.46; CI:1.28–1.66; tDMARD naïve HR:1.63; 95% CI: 1.44–1.83) than with abatacept.

Conclusion

RA Medicare Fee-For-Service beneficiaries who either switched or initiated abatacept have a lower infection-related hospitalization risk and cost compared to patients who switched to or initiated other tDMARDs.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is one of the most common autoimmune diseases, affecting nearly 1.3 million people in the USACitation1. RA is characterized by chronic inflammation of the joints, which can ultimately lead to cartilage and bone destructionCitation2. Though not directly life-threatening, RA severely impacts patients’ quality of life and imparts a major economic burden on healthcare systems and societyCitation3. RA contributes $19.3 billion (in 2005 US$) in direct and indirect costs in the USA annuallyCitation4.

The treatment of choice in RA is a group of medications known as disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). Initial treatment of active RA is typically with a conventional DMARD (cDMARD) such as methotrexate, sulfasalazine, or leflunamideCitation5,Citation6. Patients who are intolerant or show an inadequate response to cDMARDs are often treated with targeted disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (tDMARDs). There are multiple classes of tDMARDs including tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFis) (adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, golimumab, and infliximab), anti-interleukin-6 agents (tocilizumab), anti-CD20 agents (rituximab), T-cell costimulation modulators (abatacept), and Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors (tofacitinib) Citation7.

The immunomodulatory effects of RA, immunosuppressive treatments, and immunocompromising comorbidities all contribute to an increased risk of infection among RA patientsCitation8. RA patients have nearly twice the rate of infection compared with matched non-RA controls, and are at excess risk of infections requiring hospitalizationCitation8,Citation9. The most common infections associated with RA are pneumonia, skin and soft tissue infections, urinary tract infections, bacteremia, and sepsisCitation10. In a study of veterans in treatment for RA, 48% of tDMARD switching was due to adverse events (AEs) and 43% was due to lack of efficacyCitation11. Adaptive cellular immunity is impaired in RA patients by a constricted T-cell receptor repertoire, which is crucial for naïve T-lymphocytes to recognize all potential harmless and harmful antigensCitation9. In addition, clonal expansion of naïve T-cells in response to a previously unknown antigen is significantly reduced in RA patients, weakening protection against infectious diseases. Furthermore, neutropenia is common in RA patients due to increased pathological immune complexes or direct anti-neutrophil antibodies. These disease-related alterations of the immune system in RA patients all increase the risk of infections in RACitation10.

In addition to the disease itself, therapy with corticosteroids and tDMARDs may predispose RA patients to infection. Glucocorticoids significantly increase the risk of infection by a factor of 2 and 4 in RA patients receiving 7.5 mg/day to 14 mg/day and ≥15 mg/day, respectively. Medications in the TNFi class increase the risk of serious infection by up to twofold in RA patients. Meta-analyses suggest a similar increase with non-TNFi biologics. Comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and chronic kidney disease, as well as factors such as age, female gender, and smoking, may also increase infection risk in RA patientsCitation12,Citation13. Accurate assessment of the risk of infection in RA patients could inform clinical decision-making to reduce and prevent the occurrence of infections. Recently validated, the Rheumatoid Arthritis Observation of Biologic Therapy (RABBIT) risk score determines the risk of serious infection in individual RA patients based on clinical and treatment informationCitation12. Additional research must be conducted to determine the contribution of each risk factor to the overall infection risk in RA patients.

In RA patients with prior exposure to a biologic agent, exposure to etanercept, infliximab, or rituximab was associated with a greater 1-year risk of hospitalized infection compared with exposure to abataceptCitation13. Among RA patients who experienced a hospitalized infection while on TNFi therapy, abatacept and etanercept were associated with the lowest risk of subsequent infection compared with other biologic therapiesCitation14. Though previous studies evaluated patients who received any biologics and/or targeted synthetic DMARD treatment, most patients in the USA use TNFi as their first DMARD. Therefore, further studies are needed to investigate patients who use TNFi in the past since.

There is limited information on the costs associated with infection-related hospitalizations in RA patients. Furthermore, potential differences in the risk of infection-related hospitalizations associated with the use of various tDMARDs in Medicare patients who are TNFi-experienced have not been evaluated in patients naïve to tDMARD treatment till date. The current study used the 100% Medicare Fee-for-Service (FFS) claims database to evaluate the impact of tDMARDs among RA patients on the risk and cost of infection-related hospitalizations during follow-up. More specifically, among patients who were either TNFi-experienced or tDMARD naïve, we evaluated the impact of initiation or switch to abatacept, TNFis, and other non-TNFis on infection-related hospitalization risk and costs in the USA.

Methods

Study design and data source

This was a retrospective observational study using 100% Medicare FFS (Part A, B & D) claims and enrolment data from 01 January 2009 through 31 December 2017. The study cohort was derived from the 100% sample of the Medicare research identifiable files, which included Part A and Part B FFS claims data, and Prescription Drug Event (PDE) data for all Part D plans. The identifiable claims data comprised all medical and pharmacy encounters including hospital claims, emergency department (ED) visits, skilled nursing facility stays, hospital outpatient services/ambulatory surgical centre services, physician office visits (including physician administered treatments), home health services/durable medical equipment, hospice care, and pharmacy utilization.

Study population

Beneficiaries ≥65 years of age with a diagnosis of RA (≥1 inpatient claim or ≥2 outpatient (OP) medical claims on 2 different dates with an ICD-9-CM/ICD-10-CM diagnosis code for RA in any position during 12 months prior to the index event) were eligible for the study. The study cohorts consisted of (1) patients who were TNFi-experienced and switched to a subsequent different tDMARD treatment (subsequent tDMARD claim served as an index), and (2) patients who were tDMARD naïve and initiated either abatacept, TNFi or other non-TNFi as their first tDMARD (first tDMARD claim served as an index). TNFi’s included adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, golimumab, and infliximab, while other non-TNFi’s included anakinra, sarilumab, tocilizumab, baricitinib, rituximab, and tofacitinib. Intravenously administered drugs were identified via Part B medical claims whereas orals and subcutaneously administered drugs were identified via Part B and D pharmacy claims. We used the Medicare enrollment data and patients with Medicare Advantage (Part C) enrollment indicator were excluded. Patients with medical or pharmacy claim for more than one type of tDMARD on the index date and diagnosis of autoimmune conditions (i.e. Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, Wegener’s granulomatosis, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and polyarteritis nodosa) at any time during the baseline were excluded. Furthermore, patients with evidence of cancer during baseline or follow-up period or prescription data validity issues (e.g. invalid or missing days’ supply that could not be easily imputed from available information) from pharmacy claims were excluded. Among tDMARD naïve RA patients, beneficiaries with use of any tDMARD within 12 months before the index date were excluded from the study. Both TNFi-experienced and tDMARD naïve groups were followed from index date for a period of maximum 36 months and ended at the earliest of the following: (1) patient disenrollment; (2) end of study period; (3) discontinuation or switch of index treatment; (4) death during follow-up; (5) 36 months post-index. Discontinuation was defined as a 2 times gap in days supply from end of day’s supply of index drug. Patients who discontinued the index drug, last date of follow-up was the last day of supply for index drug + 90 days (index drug + days supply + 90 days). Patients who switched to another tDMARDs during follow-up, last date of follow-up was the drug switching date.

Study outcomes

Infection-related hospitalization risk and costs among TNFi-experienced and tDMARD naïve RA patient cohorts were the primary endpoints. Further, infection-related costs were further broken down into following infection types: 1) pneumonia; 2) bacterial respiratory infection; 3) sepsis; 4) skin and soft tissue infection; 5) joint infection; 6) genitourinary infection. The medical services related to these infection types were defined as any inpatient medical services with at least one diagnosis code for these infection types in any position of the inpatient claims. To account for the variable follow-up period, direct infection-related hospitalization costs outcomes were evaluated on a per-patient-per-month (PPPM) basis. All costs were inflation adjusted to 2019 cost levels using the Consumer Price Index (CPI) medical care component. We adopted the payer perspective for estimating costs. Rate of infection-related hospitalization were reported as per 1000 patients per month (P1000PPM).

Statistical analysis

Patient profiles for included patients were evaluated during the baseline period for the study cohorts. Baseline demographics and patient characteristics including age, gender, US geographic region, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score, previous glucocorticoid use, history of infection, and comorbid conditions were collected. Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate differences in patient demographics, clinical characteristics, healthcare resource use (HCRU), and costs for the study cohorts. A p value of <.05 was considered statistically significant. For this study, infection-related hospitalization risk and costs were reported by tDMARD therapies (i.e. Abatacept, TNFi, and other non-TNFi) for each study cohort. Outcomes were compared between tDMARD treatments by using descriptive statistics (unadjusted) as well as multivariable regression analyses (adjusted). A two-part generalized linear model with a log link function and gamma distribution was used to evaluate potential differences in the costs associated with infection-related hospitalizations. The adjusted risk of infection-related hospitalization was evaluated using Cox proportional hazard model. Hazard ratios (HR) were compared between the abatacept, TNFi, and other non-TNFi therapies.

Sensitivity analysis

To test for the robustness of the results to the exclusion of patients with other autoimmune diseases (i.e. Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, Wegener’s granulomatosis, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and polyarteritis nodosa), sensitivity analysis was conducted in which patients with other autoimmune diseases were included. We evaluated the impact of allowing patients with autoimmune conditions on the infection-related hospitalization risk and costs during follow-up.

Results

Cohort selection and baseline characteristics

Among TNFi-experienced cohort, a total of 16,647 Medicare FFS patients met the study criteria, of whom 6,343 patients switched to abatacept, 5,054 switched to another TNFi, and 5,250 switched to other non-TNFi (Supplemental Figure 1). Among tDMARD naïve cohort, a total of 30,439 Medicare FFS patients met the study criteria, of whom 6,303 patients initiated abatacept, 18,032 patients initiated a TNFi, and 6,104 initiated other non-TNFi (Supplemental Figure 1). Patient demographic and clinical characteristics among both TNFi-experienced and tDMARD naïve cohorts are shown in . For both TNFi-experienced and tDMARD naïve cohorts, abatacept (>90%) and other non-TNFi (>80%) were primarily administrated by intravenous route, while TNFi (>50%) were administered through subcutaneous route. Additionally, majority of the population were white and females located in the southern region of the USA with the average age around 73 years. Overall, the mean Charlson Comorbidity Scores (CCI) were non-differential (between 4 and 5) through all tDMARD groups. Additionally, majority of the RA patients had comorbid conditions for hypertension (>77%) and about a quarter of patient cohorts had diabetes ().

Table 1. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics among TNFi-experienced and tDMARD naïve patient cohorts.

Infection-related hospitalizations at baseline and follow-up

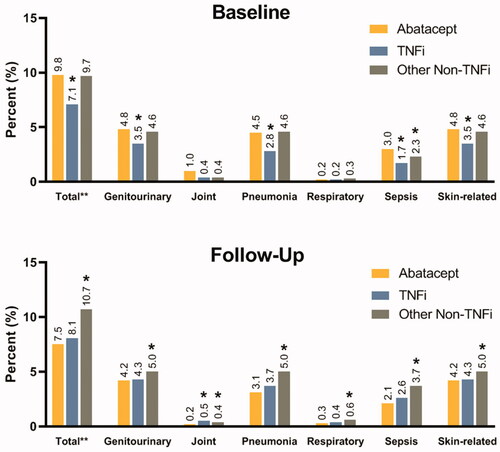

Among TNFi-experienced cohort, infection-related hospital visits at baseline were significantly higher in those who received abatacept at index (9.8%) in comparison to patients who received another TNFi (7.1%, p < .0001), however, they were non-differential when compared to patients who received other non-TNFi (9.7%, p = .77) (). During baseline, a significant number of patients had infections related to genitourinary (TNFi-experienced: 26–29%; tDMARD naïve: 3–5%), pneumonia (TNFi-experienced: 8–11%; tDMARD naïve: 2–5%), and skin-related (TNFi-experienced: 9–10%; tDMARD naïve: 3–5%) (). During follow-up, infection-related hospital visits were significantly lower in those who received abatacept (7.5%) in comparison to patients who received other non-TNFi (10.7%, p < .0001), however, they were non-differential when compared to patients who received another TNFi (8.1%, p = .21) (). Average number of infection-related hospital visits P1000PPM were also lower in abatacept users (6.5) in comparison to TNFi (8.0; p = .21) and other non-TNFi (9.7; p = .05) groups (). Additionally, only patients who received abatacept have a decline in infection frequency during follow-up period compared to baseline. Percentage of patients with infection-related hospitalization varied by infection type. During both baseline and follow-up, majority of infection-related hospitalization visits were for genitourinary, pneumonia, or skin-related infection types ().

Figure 1. TNFi-experienced patient cohort: distribution of percent patients with infection-related hospital visits at baseline and follow-up by infection type. *indicate values were significant at <0.0001 level of significance. Note: The infection sites were not mutually exclusive. Patients may have experienced more than one type of infection during the hospital stay. Patients with multiple infections during follow-up were counted only once for the estimation of the total percent.

Table 2. Infection-related hospital visits at baseline and follow-up among TNFi-experienced and tDMARD naïve patient cohorts.

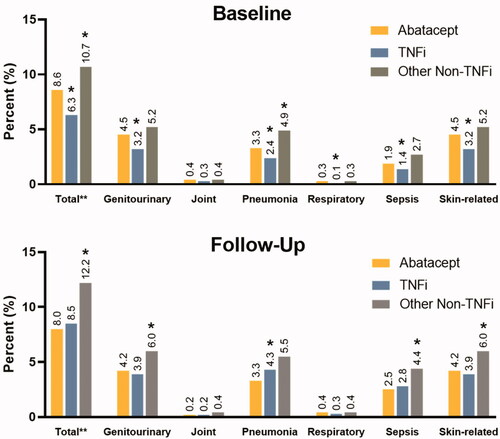

Among tDMARD naïve cohort, a similar trend of reduced infection-related hospitalization was observed during follow-up in the abatacept arm. Infection-related hospital visits at baseline were significantly lower in those who received abatacept at index (8.6%) in comparison to patients who received non-TNFi (10.7%, p < .0001), however, they were significantly higher when compared to patients who received TNFi (6.3%, p < .0001) (). Similar to TNFi-experienced cohort, percentage of patients with infection-related hospitalization varied by infection type. During both baseline and follow-up, majority of infection-related hospitalization visits were for genitourinary, pneumonia, or skin-related infection types (). During follow-up, infection-related hospital visits were lower in those who received abatacept (8.0%) in comparison to patients who received a TNFi (8.5%, p = .26) or other non-TNFi (12.2%, p < .0001) (). Average number of infection-related hospital visits P1000PPM were also lower in abatacept users (6.4) in comparison to TNFi (7.8; p = .52) and other non-TNFi (11.9; p = .01) groups ().

Figure 2. tDMARD naïve patient cohort: distribution of percent patients with infection-related hospital visits at baseline and follow-up by infection type. *indicate values were significant at <0.0001 level of significance. Note: The infection sites were not mutually exclusive. Patients may have experienced more than one type of infection during the hospital stay. Patients with multiple infections during follow-up were counted only once for the estimation of the total percent.

Infection-related hospitalization costs during follow-up

Among TNFi-experienced cohort, during follow-up, the direct PPPM costs associated with infection-related hospitalization were lower for abatacept users in comparison to TNFi and other non-TNFi users (). After controlling for potential confounding variables, infection-related hospitalization costs PPPM were significantly higher in patients treated with TNFi’s (cost difference: $74; 95% CI: $44–$105) and other non-TNFi’s (cost difference: $68; 95% CI: $44–$92) than in those treated with abatacept (). Furthermore, the PPPM cost was lower in follow-up than baseline periods for abatacept users, but the opposite for TNFi and other non-TNFi users ().

Table 3. Comparison of infection-related hospitalization costs by tDMARD therapies among TNFi-experienced and tDMARD naïve patient cohorts.

Similar to the TNFi-experience cohort, among the tDMARD naïve cohort, during follow up, the direct PPPM costs associated with infection-related hospitalization were lower for abatacept users in comparison to TNFi and other non-TNFi users (). After controlling for potential confounding variables, infection-related hospitalization costs PPPM were significantly higher in patients treated with TNFi’s (cost difference: $42; 95% CI: $25–$59) and other non-TNFi’s (cost difference: $60; 95% CI: $38–$81) than in those treated with abatacept (). The cost was lower in follow-up than in baseline periods for abatacept and other non-TNFi users, but the opposite for TNFi users ().

Sensitivity analysis gave similar results as the original study analysis for the TNFi-experienced and tDMARD naïve cohorts. The PPPM infection-related hospitalization costs was the lowest for abatacept users in comparison to TNFi and other non-TNFi users ().

Risk for infection-related hospitalization

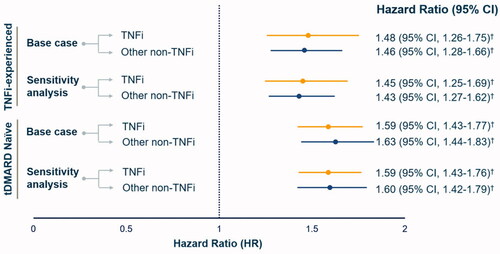

Among both TNFi-experienced and tDMARD naïve cohorts, after adjusting for differences in patient demographic and clinical characteristics, Cox regression analysis showed that the risk for an infection-related hospitalization was significantly higher for RA patients treated with TNFi’s (HR for TNFi-experienced: 1.48, 95% CI: 1.26–1.75, p < .0001; HR for tDMARD naïve: 1.59, 95% CI: 1.4–1.8, p < .0001) and other non-TNFi’s (HR for TNFi-experienced: 1.46, 95% CI: 1.28–1.66, p < .0001; HR for tDMARD naïve: 1.63, CI: 1.4–1.8, p < .0001) than in those treated with abatacept (). In the unadjusted analysis, TNFi (HR: 1.18, 95% CI: 1.03–1.37) and non-TNFi users (HR: 1.40, 95% CI: 1.22–1.60) experienced a higher risk of infection-related hospitalization compared to abatacept users in the TNFi-experienced cohort. Baseline infection-related hospitalization (HR: 1.42, 95% CI: 1.23–1.64, p < .0001), CCI score of 5+ (HR: 2.59, 95% CI: 2.13–3.14, p < .0001), and glucocorticoid use (HR: 1.31, 95% CI: 1.12–1.53, p = .0007) were independent predictors of infection-related hospitalization. Both the unadjusted and adjusted findings were consistent for the naïve cohort. Sensitivity analysis showed the results to be consistent and robust across both study cohorts ().

Figure 3. Comparison of adjusted infection-related hospitalization risk by tDMARD therapies among TNFi-experienced and tDMARD naïve patient cohorts. Note: HR were estimated by comparing TNFi and other non-TNFi to abatacept users i.e abatacept group served as a reference. † indicate values were significant at <0.0001 level of significance.

Discussion

Rheumatoid arthritis is one of the most common autoimmune disease. RA has been previously shown to be associated with increased risk of infectionCitation15. Patients with RA have nearly twice the rate of infection compared to the general populationCitation15. Infection-related hospitalizations are a significant economic burden in the Medicare populationCitation16. Therefore, it is important to understand the clinical and economic burden associated with infection-related hospitalizations among RA Medicare FFS patients treated with tDMARDs. To our knowledge, our real-world study is the first study to use 100% sample of Medicare FFS beneficiaries to assess the risk and costs of infection-related hospitalization in RA patients who were TNFi-experienced or tDMARD naïve.

Among TNFi-experienced cohort, abatacept users had a higher percentage of patients with infection-related hospitalization in the baseline compared to TNFi users. However, during follow-up, for both cohorts, patients in abatacept group had a lower percentage of patients with infection-related hospitalization than patients in either the TNFi. Our study is consistent with previous studies that have shown a lower rate of infection-related hospitalizations for patients treated with abatacept compared to TNFis and other non-TNFis in the biologic DMARD (bDMARD)-experienced Medicare patients populationCitation13,Citation17. The cost of infection-related hospitalization PPPM cost was lower in patients treated with abatacept compared to TNFi. Further, the risk for an infection-related hospitalization following initiation or switch of abatacept was significantly lower in comparison to patients who initiated or switched to TNFi. The cost of infection-related hospitalization PPPM cost was lower in patients treated with abatacept compared to TNFi.

Some limitations associated with this study and observational studies in general need to be acknowledged. Claims data exist mainly for billing and reimbursement purposes thus, there is a possibility for errors in documentation of medical conditions and outcomes which may lead to patient misclassification either due to miscoding or misdiagnosis. As claims data only captures those disease entities and variables that have their own specific billing codes, this study cannot be used to determine cause and effect. In comparison to cross-sectional and case–control study design, this retrospective cohort study will have higher internal validity. As for all observational studies, treatments are prescribed on the basis of clinical judgment. Therefore, comparisons of patients on different treatment regimens will likely be confounded because there are differences in disease severity and risk of the events of interest (e.g. patients receiving one tDMARD abatacept are likely to be different in many ways from patients receiving other tDMARDs). Potential confounding variables were controlled for via appropriate study design and statistical modelling. However, the possibility of residual confounding from unmeasured factors cannot be excluded. Conclusions regarding the differential risk in serious infections may not be generalizable to specific mechanism of action (MOAs) within the non-TNFi arm. Rituximab and tocilizumab accounted for majority of the treatment within the non-TNFi arm; tofacitinib was used in less than 13% of patients.

Even though there are some limitations to the study, there are several beneficial aspects of the use of data from a large, nationally representative US Medicare claims database. Overall, the dataset is comprehensive because it incorporates all medical and pharmacy claims of Medicare FFS patients and allows for longitudinal analysis of a large US patient sample. A major key strength of retrospective database studies is that it allows observation of patients who are often under-represented in clinical trials (e.g. those with comorbidities and the elderly population). Since prescribing patterns in the real-world are broader and less limiting, the retrospective analysis provides a more comprehensive picture of how medications are used by clinicians in routine practice and the adherence of treatments. Many of the medications being studied are relatively new to the market, and this database captures the utilization of these newer drugs. Our study provides a better understanding of the RA population in real-world clinical practice as compared to the controlled conditions of a clinical trial.

Overall, among both TNFi-experienced and tDMARD naïve Medicare FFS beneficiaries with RA, patients who initiated or switched to abatacept had lower risk and cost of infection-related hospitalization in comparison to patients who initiated or switched to TNFi’s or other non-TNFi’s. Results from this study favors use of abatacept in comparison to other tDMARDs such as TNFis as it can potentially help in reducing the clinical and economic burden associated with infection-related hospitalization in Medicare patients with RA. Future research in needed to compare abatacept with each drug within the non-TNFi arm at the mechanism of action level (Janus kinase inhibitors, B-cell depleting agent, interleukin-6 inhibitor).

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This research has been funded by Bristol Myers Squibb.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

The analysis was conducted independently by Avalere Health. BMS and Avalere Health collaborated on study design and interpretation of results. Vardhaman Patel and Francis Lobo are BMS employees and shareholders. Zulkarnain Pulungan, Anne Shah, Mahesh Kambhampati, and Allison Petrilla are employees of Avalere Health. All authors contributed towards the study design, analysis, interpretation of results and manuscript writing. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

VP designed the study, interpreted the results and supported the manuscript writing. ZP, AS and MK assisted with study design, conducted the analysis and interpreted the results. AS supported the manuscript writing. FL interpreted the results and supported the manuscript writing. AP supervised the study design, analysis, interpretation of results and manuscript content development.

Previous presentations

A portion of these results were presented at the 2019 American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/Association of Rheumatology Professionals (ARP) Annual Meeting; 2019 Nov 11; Atlanta, GA.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (48.7 KB)Acknowledgements

This study was sponsored by Bristol Myers Squibb. Bristol Myers Squibb participated in the interpretation of data, review and approval of publication. Anny Wong and Sudeepti Puhuja provided research support, data interpretation, and manuscript writing for the study.

Data availability statement

The data described in this paper are sourced from CMS Medicare Fee-for-Service claims and enrollment data. The analytic file constructed for this analysis cannot be shared due to protections of patient privacy. Researchers may request use of CMS data through ResDAC.

References

- Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, et al., National Arthritis Data Workgroup. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:15–25.

- Pruijn GJ, Wiik A, van Venrooij WJ. The use of citrullinated peptides and proteins for the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:203.

- Brooks PM. The burden of musculoskeletal disease-a global perspective. Clin Rheumatol. 2006;25:778–781.

- Birnbaum H, Pike C, Kaufman R, et al. Societal cost of rheumatoid arthritis patients in the US. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26:77–90.

- Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol Hoboken NJ. 2016;68:1–26.

- Smolen JS, Landewé R, Breedveld FC, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2013 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:492–509.

- Stevenson M, Archer R, Tosh J, et al. Adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, certolizumab pegol, golimumab, tocilizumab and abatacept for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis not previously treated with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and after the failure of conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs only: systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2016;20:1–610.

- Han G-M, Han X-F. Comorbid conditions are associated with healthcare utilization, medical charges and mortality of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35:1483–1492.

- Doran MF, Crowson CS, Pond GR, et al. Frequency of infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis compared with controls: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:2287–2293.

- Listing J, Gerhold K, Zink A. The risk of infections associated with rheumatoid arthritis, with its comorbidity and treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford)). 2013;52:53–61.

- Oei HB, Hooker RS, Cipher DJ, et al. High rates of stopping or switching biological medications in veterans with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27:926–934.

- Zink A, Manger B, Kaufmann J, et al. Evaluation of the RABBIT Risk Score for serious infections. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1673–1676.

- Yun H, Xie F, Delzell E, et al. Comparative risk of hospitalized infection associated with biologic agents in rheumatoid arthritis patients enrolled in medicare. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:56–66.

- Yun H, Xie F, Delzell E, et al. Risk of hospitalised infection in rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving biologics following a previous infection while on treatment with anti-TNF therapy. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1065–1071.

- Smitten AL, Choi HK, Hochberg MC, et al. The risk of hospitalized infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:387–393.

- Torio CM, Moore BJ. National Inpatient Hospital Costs: The Most Expensive Conditions by Payer, 2013: Statistical Brief #204. In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2006 [accessed 2019 Dec 5]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK368492/

- Pawar A, Desai RJ, Solomon DH, et al. Risk of serious infections in tocilizumab versus other biologic drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a multidatabase cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:456–464.