Abstract

Aims

Clinical and economic outcomes associated with an early discharge protocol for cementless total hip arthroplasty (THA) via a direct anterior approach (DAA) on a standard table without a dedicated traction table) were assessed. These outcomes were compared against a benchmark of THA care approximated from a national database.

Materials and methods

This retrospective, observational, comparative cohort study evaluated 250 patients receiving THA with a standard table DAA approach under an early discharge protocol at a medical center in Japan between 2016 and 2017 (intervention). Patients were propensity score-matched to a standard care control group comprised of THA patients within the Japan Medical Data Center database. A generalized linear model (GLM) using gamma distribution with log-link compared hospital length of stay (LOS) and total cost. Post-operative function and pain (Japanese Orthopaedic Association hip score [JOA] and Japanese Orthopaedic Association Hip Disease Evaluation Questionnaire [JHEQ]) were assessed for DAA patients.

Results

After propensity score matching, 239 patients were included in each cohort. The patients in the intervention and control group were comparable in regard to age, gender, comorbidities, and procedure year. Adjusted hospital LOS for DAA as part of an early discharge protocol was significantly shorter than for control patients (4.76 vs. 25.36 days). Adjusted total costs were significantly lower (29%) for the intervention group (¥1,613,800 vs. ¥2,254,757; US$14,390 vs. US$20,105). The 3-month follow-up complication rate was 0.42% (superficial infection) for intervention vs. 3.35%. The intervention group had no readmissions and post-operative function and pain scores significantly improved (JHEQ pain score 7.2 ± 5.0 to 24.2 ± 4.6, JOA 48.4 ± 12.8 to 94.3 ± 7.0; p-value < .001).

Limitations

The study is not randomized and EMR and administrative claims data may lack information (i.e. some clinical variables) required for inference. Also, the data may not represent the whole Japanese population.

Conclusions

An early discharge protocol demonstrated compatibility with standard table DAA in a Japanese hospital, providing cost savings, while maintaining reliable clinical outcomes.

Introduction

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is an effective treatment for patients with end-stage arthritic hip conditionsCitation1. Most patients will experience a reliable reduction in pain and increase in function, however, variation exists in the rate of early recovery, hospital length of stay, and the rate of early complications such as dislocation, peri-prosthetic fracture, and early loosening. There are various surgical approaches and femoral and acetabular implants available for use in THACitation2,Citation3. Surgical approach and implant choices reflect different philosophies regarding the type of fixation, design features, materials, and patient profilesCitation4.

Traditional hip replacement surgery involves making an incision on the side of the hip (lateral approach) or the back of the hip (posterior approach). These approaches typically require significant cutting and sectioning of both muscle and ligaments, which may result in increased pain after surgery and prolonged recovery. Failure of these muscles to heal after surgery may increase the risk of hip dislocation, which is one of the leading cause of hip replacement revision surgeryCitation5. Hip precautions after surgery (e.g. no bending greater than 90 degrees, no crossing legs, no excessive rotation) are generally required to minimize the risk of dislocation.

THA using the direct anterior approach (DAA) has seen a global resurgence in recent yearsCitation6. Increased demand for minimally invasive techniques, new orthopedic tables, modern arthroplasty implants, fluoroscopy, computer navigation, improved care management, and patient demand has contributed to the rise in popularityCitation7. The most recent Japan Arthroplasty Register annual report indicates that the anterior approach in THA has grown to represent over 25% of all THA cases in JapanCitation8. As DAA uses the intermuscular and inter-nervous planes, it has no risk of denervation of the hip abductor muscles even if it is extended distally or proximallyCitation9. Evidence has shown that this minimally-invasive approach may possibly result in shorter incision lengthCitation10–12, less blood lossCitation10, shorter hospital length of stay (LOS)Citation11, reduced risk of dislocationCitation13, earlier functional recoveryCitation10, less painCitation10–12,Citation14, reduced narcotic consumptionCitation11,Citation14, less infectionCitation13, better hip functionCitation12,Citation14, and faster return to work and activities for patientsCitation10.

Some surgeons prefer the use of standard operating room tables for DAA (i.e. “table-less”, “off-table” or “standard table” DAA) rather than the use of specialized traction tables. This requires no additional equipment and may be performed in any size operating room. Regular operating room tables facilitate easy patient positioning and allow simultaneous bilateral procedures. Direct comparison of leg lengths and range of motion and stability assessment is easily performed as the limb is draped freeCitation15,Citation16. The surgeon maintains control of the limb, making iatrogenic fracture less likelyCitation17. The patient is positioned so that the gluteal fold is at the break in the table, which is then used as a fulcrum to elevate the femurCitation15,Citation16.

Variation in THA also exists with respect to hospital discharge protocols employed and the associated hospital LOSCitation18. Data from the Japanese Medical Data Center (JMDC) databaseCitation18 and medical literature in Japanese patientsCitation19–21 reveals average LOS ranging from 28.6–58.7 days per patient. Clinical pathways and care programs in THA have undergone considerable changes in many countries over the past 10 years, focusing on evidence-based methods related to the surgical procedure and post-discharge function, allowing for earlier dischargeCitation22. The systematic implementation of evidence-based perioperative care protocols (“fast-track” or “enhanced recovery pathways”), such as those developed by the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society may reduce hospital LOS and complications for THACitation23. A meta-analysis of the evidence for ERAS perioperative care protocols found that their implementation significantly reduced the mortality rate, transfusion rate, incidence of complications, and LOS in patients undergoing THACitation24. However, ERAS perioperative care protocols did not have a significant impact on the range of motion (ROM) and 30-day readmission rateCitation24.

The aging population and the increasing availability of new medical technologies have led to growing pressure on governments worldwide to contain healthcare costsCitation25. Japan is one of the fastest aging countries in the world and consequently faces a rapid rise in healthcare expenditures, the implementation of ERAS in elderly patients during THA can reduce LOS without compromising the patient’s outcome or increasing the risk of complicationsCitation26.

Economic evaluation for decision-making is gradually gaining importance in JapanCitation27. The more systematic use of economic evaluations for new technologies and treatment pathways is likely to increase the efficiency and sustainability of the healthcare systemCitation27. Japan’s health system provides universal coverage for the entire population. The reimbursement for medical services is done mainly on a fee-for-service basis. However, a small part of the care is paid through diagnosis procedure codes (DPC). This system was introduced in 2003 to encourage case-based reimbursement. Unlike diagnostic related group (DRG) systems, DPC is not a procedure-based system, but a per diem payment based on patient classification with different tariffs depending on the time in hospital.

A better understanding of the clinical and economic outcomes associated with an early discharge program combined with standard table DAA would assist surgeons and other healthcare decision-makers in elucidating the value associated with this pathway of care and may provide insights into opportunities for improving THA patient care management. Data regarding the “real-world” safety and effectiveness of standard table DAA combined with an early discharge program is sparse. The objective of the current study was to evaluate the patient medical costs and 90-day resource utilization outcomes associated with cementless THA via a standard table DAA as part of an early discharge protocol at a medical center in Japan. These costs and resource utilization outcomes were compared against a benchmark of THA care approximated from the JMDC database.

Materials and methods

Data sources

This retrospective, observational, comparative cohort study compared the standard table THA via DAA combined with an early discharge program vs. standard of care using electronic medical record (EMR) data from Funabashi Orthopedic Hospital, a large Japanese orthopedic center and administrative claims data from the JMDC database, respectively. The study was approved by the hospital Ethics Review Committee on 20 December 2018, approval number 2018046. Our hospital has been using DAA without the use of specialized traction table systems for THA for more than 10 years. Starting from the most recent dataset in 2018, data were extracted from the hospital EMRs through a retrospective review of 250 consecutive standard table DAA patients performed in 2016–2017. Standard table DAA was performed by five surgeons in total, three of who were DAA experts and two who had some training and experience in performing DAA. All patient-level data were de-identified and extracted into a fully anonymized dataset.

Control patients within the JMDC claims database reflected “standard care” from 2016 to 2017 and were used for benchmarking results observed for the standard table DAA (intervention) cohort at the hospital. THA would have been carried out with a range of surgical approaches, which could include posterior, lateral and anterior. JMDC Claims Database is an epidemiological receipt database that has accumulated receipts (inpatient, outpatient, dispensing) and medical examination data received from multiple health insurance associations in Japan since 2005. The cumulative dataset is approximately 7 million subjects (as of September 2019), covering about 10% of the population in health insurance associations. Each patient can be tracked by a consistent unique identifier as long as the patient does not leave a payer which he/she currently belongs to.

Patient population

Patients aged 18 years or older who underwent elective THA and had a minimum of three months of post-discharge follow-up data were considered for inclusion in the study. Consecutive patients from the hospital who underwent standard table DAA with the CorailFootnotei Stem and PinnacleFootnoteii Cup as part of an early discharge protocol were compared to standard care patients from the JMDC database who had “arthroplasty with prosthetic replacement, hip (procedure ID 150050410)”. Patients were excluded if they had a hip-related fracture as a primary diagnosis for the index procedure, were missing baseline age or gender information, or had bilateral THA within the study period (up to three months after discharge).

Patients in the standard table DAA group (intervention cohort) were included in a standard hospital protocol designed for early discharge to home. Multiple patients are typically admitted on the day prior to surgery, operated on the same day, and then receive four days of group rehabilitation after the day of surgery prior to being discharged home. Efficient surgery schedule and effective patient education and support to facilitate group-based learnings & physiotherapies are integral components of the standardized early discharge protocol. The pain management protocol aimed to minimize opioid use. It included NSAIDs administered immediately after anesthetic; acetaminophen (1,000 mg IV) the day after surgery depending on patient weight; metoclopramide (20 mg IV), dexamethasone (3.3 mg IV), and antiemetic 1 mL SC. The patient education program was initiated early, so that patients were familiarized with the postoperative rehabilitation program before the surgery.

Study measures

Patient demographics that were evaluated included age, gender, and index procedure year. Patient clinical characteristics that were evaluated were the presence of comorbidities (i.e. obesity defined as body mass index [BMI] > 27.5 kg/m2, diabetes [Type I or Type II]) and the primary diagnosis for THA (i.e. osteoarthritis (including osteoarthritis due to developmental dysplasia), osteonecrosis, rheumatoid arthritis, tumor, other inflammatory arthritis, and dislocation).

The outcomes of interest evaluated were (1) comparative total acute costs (for the intervention arm this included total medical expenses during the hospitalization, and for the control arm this included Diagnostic Procedure Combination [DPC] and inpatient costs from JMDC claims data); (2) healthcare resource use (HRU) within 90 days of discharge including the frequency and cost of outpatient visits and admissions/re-admissions; (3) complications within 90 days of discharge (including but not limited to dislocation, aseptic loosening, infections [e.g. superficial infection, surgical site infection, prosthetic joint infection], peri-prosthetic bone fracture, implant fracture, muscle or nerve damage, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and bleeding or blood loss) and (4) hospital LOS (defined as the duration between the discharge date and date of the index procedure).

In the intervention arm only, post-operative pain and function were assessed using the Japanese Orthopaedic Association hip score (JOA)Citation28 and the Japanese Orthopaedic Association Hip Disease Evaluation Questionnaire (JHEQ; total score and pain subscale score)Citation28. JOA and JHEQ scores were evaluated and presented at baseline (i.e. pre-operatively) and at 3 months for patients in the intervention arm only.

Statistical analyses

Mitsuyasu et al.Citation20 reported mean ± SD hospital charges for THA to be ¥2,347,029 ± ¥840,339 (US$20,928 ± 7,493) in five high-volume Japanese hospitals between 2001 and 2003 (*US$1 = ¥112.15). Using a mean cost of ¥2,400,000 (US$21,400) and an SD of ¥900,000 (US$8,025), and considering a potential 10% mean cost reduction, a total sample size of 500 patients (250 from the hospital and 250 from JMDC) would be required to provide >80% power at α = 0.05 based on a two-sample two-sided t-test. A sample size of 500 patients (250 per group) was therefore chosen to allow for evaluation of HRU and complication profiles. However, since there was no previous knowledge to support the 10% cost reduction assumption in the hospital, the total cost reduction analysis (and all other HRU utilization and complication profile analyses) was considered exploratory for this study.

All study variables were analyzed descriptively, and exploratory comparisons were made using propensity score-matched samples. Frequency counts, proportions (dichotomous variables), means, medians, and standard deviations (continuous variables) were evaluated. Two sample t-tests were used for comparisons when data were approximately normal, and non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used for non-normal data. THA patients in the control group were propensity-matched to those in the intervention group on age, gender, comorbidity (obesity, diabetes), and index procedure using nearest neighbor matching with a caliper of 0.1 for the propensity score. Total acute costs and HRU were compared for the matched samples. A generalized linear model (GLM) using a gamma distribution and a log link was used to examine total costs in the matched samples after adjustment for primary diagnosis (i.e. osteoarthritis, osteonecrosis, rheumatoid arthritis and other). Post-operative pain and functional status (JHEQ and JOA) for the intervention cohort were descriptively presented.

Results

There were 250 patients in the intervention cohort and 1,304 control patients who received THA within the JMDC database prior to matching. After propensity score matching, there were 239 patients in each treatment arm.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics

presents the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics for the pre- and post-matched samples. The greatest differences between the intervention and control groups before matching were in age, diabetes as comorbidity, and the year of surgery. In the pre-matched sample, the mean (SD) age in the intervention patients was 61.89 (8.94) years, 78.40% of patients were female, 90.80% of patients had a primary diagnosis of osteoarthritis, and 74.80% of patients had their surgery in 2017. In the pre-matched sample, the mean (SD) age in the standard care patients was 57.29 (7.78) years, 75.54% of patients were female, 87.58% of patients had a primary diagnosis of osteoarthritis, and 54.91% of patients had their surgery in 2017. At time of the THA, 12.00% of intervention patients were obese and 4.80% had diabetes mellitus, whereas 11.35% of standard care patients were obese and 11.04% had diabetes mellitus. Patients with early discharge and standard table DAA were comparable to patients with standard care with respect to age, gender, comorbidity, and index procedure year.

Table 1. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics for the pre- and post-propensity score matched (PSM) samples.

Costs, healthcare resource use, and complications

presents the costs, healthcare resource use (HRU), and complications for the intervention and standard care control group. The adjusted LS-mean total cost for the intervention group (¥1,613,800 [CI 1,457,928; 1,786,336]; US$14,390 [CI 13,000; 15,928]) was significantly lower than that for the control group (¥2,254,757 [2,032,655; 2,501,128]; US$20,105 [18,124; 22,302]) (p < .001), reflecting per-patient savings of ¥640,957. Patients in the intervention group had fewer outpatient follow-up visits and lower costs for outpatient follow-up visits. There were no readmissions in the intervention group, whereas 9.21% (n = 22) of patients in the standard care group had readmissions (all-cause readmission) during the 3-month follow-up period post-discharge (p < .001). Two minor intra-operative complications were observed in the intervention cohort (fracture of the femur [n = 1], transient femoral nerve damage [n = 1]). During the 3-month follow-up period, the complication rate for intervention patients was 0.42% (n = 1 patient; superficial infection). In the control cohort, 3.35% of patients (n = 8) had complications during the 3-month follow-up period (pulmonary embolism [n = 2], surgical site infection [n = 7]). Mean (SD) LOS from procedure to discharge for the index hospitalization in the intervention group was 3.76 (0.95) days. In the standard care group from JMDC, mean (SD) LOS was 22.95 (13.68) days.

Table 2. Costs, healthcare resource use (HRU), and complications.

Post-operative function and pain – intervention cohort only

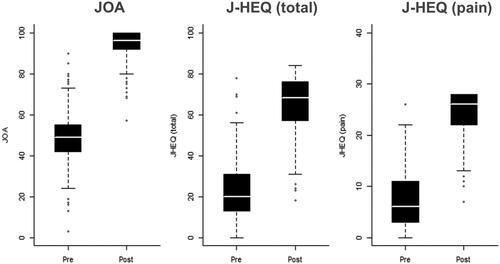

Mean functional scores (JOA and JHEQ Movement) were significantly improved at 3-months follow-up compared to pre-operative scores in the intervention group; JOA from 48.4 ± 12.8 to 94.3 ± 7.0 and JHEQ Total from 22.8 ± 14.0 to 65.1 ± 13.9 (p-values <.001; and ). Mean JHEQ Pain subscale scores were also significantly improved in the intervention group at 3-months follow-up compared to pre-operatively; from 7.2 ± 5.0 to 24.2 ± 4.6 (p-value <.001; and ).

Figure 1. Pre- and post-operative function and pain. Abbreviations. JHEQ, Japanese Orthopaedic Association Hip Disease Evaluation Questionnaire; Questionnaire; JOA, Japanese Orthopaedic Association assessment.

Table 3. Pre- and post-operative function and pain.

Discussion

Healthcare decision-makers must determine priorities for the management of patients with THA in the face of limited resources, constantly increasing demands for healthcare and the development of new interventions and treatmentsCitation29. Although THA is proven to improve patient outcomes, variation exists with respect to rates of early recovery, hospital LOS, and post-operative complicationsCitation18. An evaluation of data from the JMDC database and a review of published medical literature in Japanese patients demonstrated that there was significant variation in LOS and total costs for THA in JapanCitation18. LOS varied from 28.6–58.7 days per patient, and total cost varied from ¥2,170,000 to ¥2,632,000 (US$19,349 to US$23,469) per patientCitation19–21 [US$1 = ¥112.15].

The most recent Japan Arthroplasty Register annual report indicates that the anterior approach for THA has grown to represent over 25% of all THA cases in JapanCitation8. Standard table DAA using a standard operating room table has potential advantages in smaller operating rooms, allowing space for fluoroscopy, and providing easier access to the contralateral limb to check leg length or perform bilateral arthroplastyCitation15,Citation16. These results are promising for other hospitals considering adopting a standard hospital protocol designed for early discharge to home, combined with standard table DAA THA.

It is important to note that the reasons for the reduced LOS observed in this study are multifactorial and may include the early discharge protocol, the efficiency of the hospital, and the use of the DAA approach. The reduced LOS was only made possible due to the hospital’s desire to move toward early discharge and due to its implementation of a standard hospital protocol designed for early dischargeCitation19–21. Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathways entail patient-centered, evidence-based, multidisciplinary team-developed approaches aimed at reducing patients’ surgical stress response, optimizing patients’ physiological function, and facilitating patients’ recoveryCitation24. The core principles of ERAS include using less invasive surgical practices, reducing complications, saving costs, shortening the hospital LOS, improving patient satisfaction, and promoting faster recoveryCitation24. At the study medical center, the implementation of a specialized early discharge protocol has enabled the LOS for THA (a procedure to discharge) to be reduced to approximately 4–5 days for unilateral THA and 7 days with bilateral THA. Factors believed to be critical for achieving successful outcomes in THA patients at the study center include autokinetic movement of the foot joint immediately after surgery, specific intra- and post-op pain management designed to reduce rates of post-op nausea, early mobilization of the patient post-surgery, early patient education, successful group rehabilitation, multidisciplinary cooperation and collaboration throughout all phases, and optimal patient-centric care.

Japan is at the forefront of countries experiencing an aging societyCitation30, however, it also has a healthy population and low-cost healthcare relative to that of the United States and other Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) member countriesCitation31. Nevertheless, there are concerns that the advancement of healthcare will further increase the inflation of national healthcare costs in JapanCitation32. LOS and total costs are commonly examined short-term outcomes that are considered relevant for evaluating the economic impact after surgery. Statistics have shown that hospitalizations in Japanese hospitals are longer than those in other developed countriesCitation33. However, there are concerns that excessively reducing LOS may reduce healthcare quality, such as increasing readmission ratesCitation34,Citation35. In the current study, the reduced LOS did not compromise the healthcare quality when using complications, readmission, and the number of post-operative outpatient visits as measures.

Mean functional and pain scores for patients in the intervention group were significantly improved at 3-months follow-up compared to pre-operative scores. These findings are consistent with other published literature. Fukui et al.Citation36 evaluated JHEQ scores in 100 consecutive patients at 6 months after THA. In their study, the mean JHEQ total score improved significantly from 25.9 preoperatively to 59.1 postoperatively (p < .001), vs. an improvement from 22.8 to 65.1 in the current study. Fukui et al.Citation36 also observed a significant improvement in the JHEQ pain subscale scores similar to the current study; JHEQ Pain subscale scores in Fukui et al. improved from 8.4 to 24.2 whereas in the current study they improved from 7.2 to 24.2).

A limitation of the current study is that EMR and administrative claims data are not collected specifically for research purposes and may lack information (e.g. some clinical variables) required for inference. This study also is limited by bias inherent to retrospective single-center observational cohort studies (e.g. lack of randomization). The study data collected included limited patient demographics and patient co-morbidities; thus, not all potential confounders were available for analysis. Also, the JMDC dataset was used to benchmark standard care; it covers approximately 4% of the population and may not represent the whole Japanese population. Patients in the JMDC control group represent a heterogeneous mix of approaches to THA, potentially including a minority of patients who have received DAA. No information is available from JMDC on the patient pathway or discharge criteria, although the LOS is consistent with the published literature. It was not possible to identify the root cause of the readmissions recorded for the control cohort and it is not possible to discern whether the results are due to the enhanced recovery protocol or DAA. Therefore, no definitive comparative conclusions can be drawn for specific surgical approaches. Finally, it is acknowledged that these findings are of most relevance to the Japanese healthcare system and that the international generalizability of the work is limited given the differences in the standard length of hospital stay in other healthcare systems.

Conclusions

An early discharge patient care program demonstrated compatibility with standard table DAA in a Japanese hospital, enabling cost savings to payers while maintaining reliable clinical outcomes. These results are promising for other hospitals considering adopting standard table DAA using a cementless THA as part of an early discharge protocol. Future research is warranted to evaluate factors affecting patient recovery and to ascertain the generalizability of study results.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Johnson & Johnson (JnJ).

Declaration of financial/other relationships

AB, JM. HP and AR are employees of Johnson & Johnson (JnJ). No author received an honorarium related to the development of this manuscript.

JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

All authors were involved with conception, study design, interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, and the final approval of the version to be published.

Previous presentations

None.

Acknowledgements

Editorial assistance was provided by Natalie Edwards of Health Services Consulting Corporation and was funded by Johnson & Johnson (JnJ). The authors were fully responsible for the content, editorial decisions, and opinions expressed in the current article.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission from Funabashi Orthopedic Hospital and the Japanese Medical Data Center (JMDC).

Notes

i Corail is a registered trademark of DePuy Synthes, Warsaw, IN, USA.

ii Pinnacle is a registered trademark of DePuy Synthes, Warsaw, IN, USA.

References

- Liu X-W, Zi Y, Xiang L-B, et al. Total hip arthroplasty: are view of advances, advantages and limitations. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(1):27–36.

- Kim JT, Yoo JJ. Implant design in cementless hip arthroplasty. Hip Pelvis. 2016;28(2):65–75.

- Petis S, Howard JL, Lanting BL, et al. Surgical approach in primary total hip arthroplasty: anatomy, technique and clinical outcomes. Can J Surg. 2015;58(2):128–139.

- López-López JA, Humphriss RL, Beswick AD, et al. Choice of implant combinations in total hip replacement: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2017;359:j4651.

- Dargel J, Oppermann J, Brüggemann G-P, et al. Dislocation following total hip replacement. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111(51–52):884–890.

- Post ZD, Orozco F, Diaz-Ledezma C, et al. Direct anterior approach for total hip arthroplasty: indications, technique, and results. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(9):595–603.

- Tatka J, Fagotti L, Matta J. Anterior approach total hip replacement (THA) with a specialized orthopedic table. Ann Joint. 2018;3:42–42.

- Japan Arthroplasty Register. Annual Report 2016 [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 November 19]. Available from: jsra.info/pdf/THA(JAR2017English%20version).pdf

- Oinuma K, Tamaki T, Miura Y, et al. Total hip arthroplasty with subtrochanteric shortening osteotomy for Crowe grade 4 dysplasia using the direct anterior approach. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(3):626–629.

- Wang Z, Hou JZ, Wu CH, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of direct anterior approach versus posterior approach in total hip arthroplasty. J Orthop Surg Res. 2018;13(1):229.

- Miller LE, Kamath AF, Boettner F, et al. In-hospital outcomes with anterior versus posterior approaches in total hip arthroplasty: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Pain Res. 2018;11:1327–1334.

- Kucukdurmaz F, Sukeik M, Parvizi J. A meta-analysis comparing the direct anterior with other approaches in primary total hip arthroplasty. Surgeon. 2019;17(5):291–299.

- Miller LE, Gondusky JS, Kamath AF, et al. Influence of surgical approach on complication risk in primary total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop. 2018;89(3):289–294.

- Miller LE, Gondusky JS, Bhattacharyya S, et al. Does surgical approach affect outcomes in total hip arthroplasty through 90 days of follow-up? A systematic review with meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(4):1296–1302.

- Connolly KP, Kamath AF. Direct anterior total hip arthroplasty: literature review of variations in surgical technique. World J Orthop. 2016;7(1):38–43.

- Daniel CA, Lawrence RM, William WB, et al. “Table-less” and “assistant-less” direct anterior approach to hip arthroplasty. Reconstruct Rev. 2015;5(3):35–44.

- Macheras GA, Christofilopoulos P, Lepetsos P, et al. Nerve injuries in total hip arthroplasty with a mini invasive anterior approach. Hip Int. 2016;26(4):338–343.

- Bourcet A, Tong C, Rossi A, et al. PMS33 epidemiology and economic burden of total hip arthroplasty in Japan. Value in Health. 2019;22:S244.

- Kadono Y, Yasunaga H, Horiguchi H, et al. Statistics for orthopedic surgery 2006-2007: data from the Japanese Diagnosis Procedure Combination Database. J Orthop Sci. 2010;15(2):162–170.

- Mitsuyasu S, Hagihara A, Horiguchi H, et al. Relationship between total arthroplasty case volume and patient outcome in an acute care payment system in Japan. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(5):656–663.

- Cortese D, Landman N, Smoldt R, et al. In search of higher value in medicine in Japan and the U.S. Scotts Valley (CA): CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform; 2015.

- Berg U, Berg M, Rolfson O, et al. Fast-track program of elective joint replacement in hip and knee-patients’ experiences of the clinical pathway and care process. J Orthop Surg Res. 2019;14(1):186.

- Wainwright TW, Gill M, McDonald DA, et al. Consensus statement for perioperative care in total hip replacement and total knee replacement surgery: enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society recommendations. Acta Orthop. 2020;91(1):3–19.

- Deng QF, Gu HY, Peng WY, et al. Impact of enhanced recovery after surgery on postoperative recovery after joint arthroplasty: results from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Postgrad Med J. 2018;94(1118):678–693.

- Ikegami N, Drummond M, Fukuhara S, et al. Why has the use of health economic evaluation in Japan lagged behind that in other developed countries? Pharmacoeconomics. 2002;20(2):1–7.

- Villatte G, Mathonnet M, Villeminot J, et al. Interest of enhanced recovery programs in the elderly during total hip arthroplasty: a systematic review. Geriatr Psychol Neuropsychiatr Vieil. 2019;17(3):234–242.

- Shiroiwa T, Fukuda T, Ikeda S, et al. New decision-making processes for the pricing of health technologies in Japan: the FY 2016/2017 pilot phase for the introduction of economic evaluations. Health Policy. 2017;121(8):836–841.

- Kuribayashi M, Takahashi KA, Fujioka M, et al. Reliability and validity of the Japanese Orthopaedic Association hip score. J Orthop Sci. 2010;15(4):452–458.

- Sorenson C, Drummond M, Bhuiyan Khan B. Medical technology as a key driver of rising health expenditure: disentangling the relationship. Clin Econ Outc Res. 2013;5:223–234.

- Nakamura K. A “super-aged” society and the “locomotive syndrome”. J Orthop Sci. 2008;13(1):1–2.

- Akiyama N, Shiroiwa T, Fukuda T, et al. Healthcare costs for the elderly in Japan: analysis of medical care and long-term care claim records. PLoS One. 2018;13(5):e0190392.

- Ogura H, Komoto S, Shiroiwa T, et al. Exploring the application of cost-effectiveness evaluation in the Japanese National Health Insurance System. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2019;35(6):452–460.

- OECD Indicators. Indicators of health at a glance [Internet]. Paris (France): OECD Publishing; 2011 [cited 2016 Feb 15]. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1787/health_glance-2015-en

- Kunisawa S, Fushimi K, Imanaka Y. Reducing length of hospital stay does not increase readmission rates in early-stage gastric, colon, and lung cancer surgical cases in Japanese acute care hospitals. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0166269.

- Shimizutani S, Yamada H, Noguchi H, et al. Exploring the causal relationship between hospital length of stay and re-hospitalization among Japanese AMI patients. Appl Econ. 2015;47(22):2307–2325.

- Fukui K, Kaneuji A, Sugimori T, et al. Clinical assessment after total hip arthroplasty using the Japanese Orthopaedic Association Hip-Disease Evaluation Questionnaire. J Orthop. 2015;12(1):S31–S36.