Abstract

Aim

Multiple sclerosis (MS) poses a substantial employer burden in medically related absenteeism and disability costs due to the chronic and debilitating nature of the disease. Although previous studies have evaluated relapse, nonadherence, discontinuation, and switching individually, little is known about their overall collective prevalence and implications in employees with MS treated with disease-modifying therapies (DMTs). This study evaluated the proportion of employees with MS with suboptimal DMT year-1 outcomes and to quantify the clinical and economic burden of suboptimal year-1 outcomes from a US employer perspective.

Materials and Methods

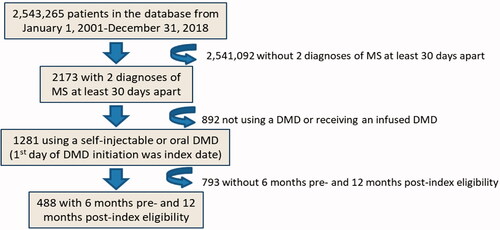

Employees with MS were selected from the Workpartners database. Eligibility criteria were: ≥2 MS diagnosis claims (ICD-9-CM 340.xx/ICD-10-CM G35) from January 1, 2010–March 31, 2019, ≥1 once-/twice-daily oral or self-injectable DMT claim (first claim = index), continuous eligibility 6-months pre-/1-year post-index, no baseline DMT, and age 18–64 years. Suboptimal year-1 outcomes included: non-adherence (proportion of days covered <80%), discontinuation (gap >60 days), switch, or relapse (MS-related hospitalization, emergency room visit, or outpatient visit with corticosteroid). A two-part logistic-generalized linear model evaluated costs.

Results

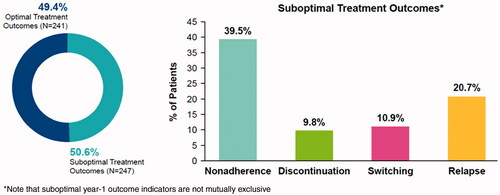

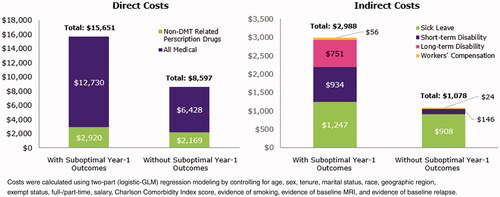

Of 488 eligible patients, half (n = 247; 50.6%) had suboptimal year-1 outcomes (39.5% non-adherence, 9.8% discontinuation, 10.9% switching, 20.7% relapse; not mutually exclusive). Employees with suboptimal year-1 outcomes had higher all-cause medical ($12,730 vs. $6,428; p < 0.0001), MS-related medical ($5,444 vs. $2,652; p < 0.0001), non-DMT pharmacy ($2,920 vs. $2,169; p = 0.0199), sick leave ($1247 vs. $908; p = 0.0274), and short-term disability ($934 vs. $146; p = 0.0001) costs. Long-term disability ($751 vs. $0; p = 0.1250) and Workers’ Compensation ($56 vs. $24; p = 0.1276) did not significantly differ.

Limitations

Administrative claims lack clinical information. Results may not be generalizable to other patients or care settings.

Conclusions

Half of the employees with MS in this sample had suboptimal year-1 outcomes (i.e. non-adherence, discontinuation, switching, or relapse). These suboptimal year-1 outcomes were associated with greater medical, sick leave, and short-term disability costs.

Graphical Abstract

The full sized graphical abstract is available for this article as supplementary material.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, demyelinating, and neurodegenerative disorder of the central nervous system. MS can lead to permanent disability and cognitive impairment, though the clinical course of MS is heterogeneous across different patient populationsCitation1. Individuals with MS may also have modifiable risk factors that can adversely affect outcomes throughout the disease course, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and chronic tobacco useCitation2.

MS is one of the leading causes of non-traumatic disability affecting young adults in the US and Europe, and the degree of physical disability is a strong predictor of gainful employmentCitation3–5. Demographic factors such as age and educational background, as well as non-motor symptoms of MS, such as pain, fatigue, and memory impairment, also significantly impact employment status in MSCitation5–7. Patients with MS who are employed tend to rate their levels of quality-of-life higher than patients with MS who are unemployedCitation8, thus emphasizing the need for optimal disease management for employed patients with MS.

MS poses a substantial employer burden in medically-related absenteeism and disability costs due to the chronic and debilitating nature of the diseaseCitation9. Since MS typically presents in patients at a younger age (20–50 years of age), impairment relating to MS can last for decades of a person’s work life and there is greater loss of productivity and quality-of-life over the patient’s lifetimeCitation10–12. The initiation of disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) that reduce relapses and disability progression may ultimately enable individuals with MS to persist in the workforceCitation13. Studies involving US employees showed a significantly lower rate of severe relapses and lower total costs over 2 years with DMT adherence vs. non-adherenceCitation14,Citation15. Prior studies also demonstrated that initiation of DMTs in employees with MS is associated with significant medical and indirect cost savingsCitation16,Citation17.

Some employees with MS, however, may have challenges with their DMT. Employees may experience suboptimal year-1 outcomes such as: relapses despite DMT treatment; non-adherence to DMTs; and DMT discontinuation with or without switching to an alternative therapy. These outcomes are not mutually exclusive; a patient may experience more than one “suboptimal year-1 outcome” at any given time.

Although previous studies have evaluated relapse, nonadherence, discontinuation, and switching individually, little is known about the overall collective prevalence of suboptimal year-1 outcomes in employees with MS treated with DMTs. Aggregating these outcomes into a single composite measure would provide an indicator of the proportion of patients affected by any of these outcomes. Subsequently, a better understanding of the real-world direct and indirect costs associated with suboptimal year-1 outcomes would provide a more comprehensive estimate of the magnitude of their economic burden. Hence, the objectives of this study were to: (1) estimate the prevalence of employees with MS and suboptimal year-1 outcomes after initiating self-injectable or oral DMTs; and (2) quantify the associated direct and indirect costs of suboptimal year-1 outcomes from an employer perspective.

Methods

Data source

WorkpartnersFootnotei is a health benefits consultant for a number of large US employers with diverse salary, job type, employee age, sex, and geographic region demographics. The employers are in a variety of industries, including manufacturing, insurance, retail, transportation, telecommunications, healthcare, grocery, and pharmaceuticals. Employers consented to have their data analyzed to learn how to improve health management and maintain relatively stable employee populations.

The Workpartners Research Reference Database (RRDb) currently includes approximately 2.8 million employees (and insured spouses/dependents) who were employed during a time between January 1, 2001 and June 30, 2019. This nontransferable database is comprised of healthcare claims, inpatient utilization, and pharmaceutical expenditures for the employees and their eligible dependents. The RRDb contains additional information not found in traditional expenditure databases, such as information on employees’ short- and long-term-disability claims, Workers’ Compensation claims, and sick-leave claims. The RRDb also contains employee-specific information on demographics, company type, job type, employment status, salary, and health plan. Prior to research use, the data were de-identified to comply with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and contractual obligations with the employer contributors. Ethics approval from an Institutional Review Board and Informed Consent were not required given the use of de-identified data and HIPAA compliance.

Study population

Eligibility criteria were employees aged 18–64 years with at least two medical claims with a diagnosis of MS at least 30 days apart (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] code: 340.xx and ICD-10-CM code: G35) from January 1, 2010 and June 30, 2019, and at least one prescription for a DMT after MS diagnosis. The date of the first DMT prescription identified in the database was defined as the index date during the study period. Employees included in the study had either a self-injectable (i.e. subcutaneous or intramuscular interferon beta-1a, interferon beta-1b, peginterferon beta-1a, or glatiramer acetate) or an oral (i.e. dimethyl fumarate, fingolimod, or teriflunomide) therapy as their index DMT. Employees were excluded if their index DMT was an infusion therapy (i.e. alemtuzumab, mitoxantrone, ocrelizumab, or natalizumab) due to challenges in accurately determining treatment discontinuation with these DMTs using this database given their infrequent dosing schedule. Employees were required to have continuous eligibility for at least 6 months before the index date (i.e. eligible to receive healthcare benefits during the 6-month time period prior to initiating their first DMT; baseline period) and 12 months after the index date (follow-up period). The 6-month pre-index period was used to capture baseline information for patients prior to their initiation of their first DMT. The study focused on the first DMT in an effort to have a more homogenous sample of patients due to the chronicity and complexity of MS.

Suboptimal year-1 outcomes

Suboptimal year-1 outcomes were ascertained during the 12-month follow-up period. Employees with MS were defined as having suboptimal year-1 outcomes if they had evidence of non-adherence to their DMT, discontinued their DMT, switched therapy, or continued to relapse despite treatment. Employees with suboptimal year-1 outcomes were compared to employees without suboptimal year-1 outcomes (i.e. employees who had none of the suboptimal year-1 outcome indicators). Relapse was defined as ≥1 MS-related hospitalization, emergency room (ER) visit, or outpatient visit with a corticosteroid claim ±7 days of the visitCitation18,Citation19. Non-adherence was defined as the proportion of days covered (PDC) <80%. PDC was calculated as the total number of days in the follow-up period in which medication was available (excluded overlapping days’ supply) divided by the duration of the observation period (i.e. 1 year). DMT discontinuation was defined as a treatment gap >60 days, and switching was defined as initiating another DMT during the follow-up period.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of employees with MS were assessed during the 6 months prior to index DMT initiation and were compared for patients with vs. without suboptimal year-1 outcomes. Demographic characteristics that were evaluated included: age at index (continuous), age group (categorical), sex, race, region (based on first digit zip codes), marital status, tenure of employment, salary, exempt/non-exempt status, and full-time/part-time status. Clinical characteristics that were evaluated included: MS relapse history (claims evidence of a relapse prior to index DMT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) prior to index DMT (claims evidence of MRI utilization), evidence of smoking, and comorbidities (overall comorbidity as measured by the Charlson Comorbidity Index [CCI] and individual rates of hyperlipidemia, hypertension, gastrointestinal disease, depression, thyroid disease, anxiety, arthritis [rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis], chronic lung disease, diabetes [type I and type II], and alcohol abuse diagnoses). These comorbidities were selected because they are prevalent in patients with MSCitation20.

Direct and indirect costs

All-cause and MS-related direct costs were assessed during the 12-month follow-up period and were compared between employees with MS, with vs. without suboptimal year-1 outcomes. All-cause and MS-related direct costs that were evaluated and compared were inpatient hospitalizations, outpatient hospital or clinic visits, ER visits, outpatient visits, laboratory tests and procedures, pharmacy, and “other”. Measures of indirect costs that were evaluated and compared were sick leave, short-term disability, long-term disability, and Workers’ Compensation.

Analyses

All study variables were analyzed descriptively. Categorical and binary variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were summarized using means and standard errors. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics and direct and indirect costs were compared between employees with MS with vs. without suboptimal year-1 outcomes.

A two-part logistic-generalized linear model (GLM) evaluated costs controlling for age, sex, tenure, marital status, race, geographic region, exempt status, full-/part-time work status, salary, CCI score, evidence of smoking, evidence of baseline MRI, and evidence of a baseline relapse. All costs were adjusted to 2018 dollars using components of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Chi-square tests evaluated differences between categorical variables and t-tests evaluated differences in continuous variables. A p-value of <0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. P-values were not adjusted for multiplicity.

Results

Of 2,173 employees with ≥2 MS diagnoses, 1,281 (59.0%) were on treatment with a self-injectable or oral DMT, and 488 (22.5%) met the required continuous eligibility criteria and were included in the study ().

Half of the employees with MS meeting study criteria (n = 247; 50.6%) had suboptimal year-1 outcomes (39.5% non-adherence, 9.8% DMT discontinuation, 10.9% DMT switch, 20.7% relapse; indicators not mutually exclusive; ).

Demographic and clinical characteristics

No significant differences in baseline demographic characteristics were observed between employees with MS with vs. without suboptimal year-1 outcomes (): mean age: 42.60 vs. 43.87 years; female: 73.7% vs. 71.4%; White/Black/Hispanic: 32.0%/5.3%/3.6% vs. 29.5%/5.8%/6.6%; married: 23.1% vs. 27.4%; and mean annual salary: $61,898 vs. $68,737, respectively. Baseline clinical characteristics were also similar for employees with MS with vs. without suboptimal year-1 outcomes (): hypertension: 14.6% vs. 16.6%; hyperlipidemia: 11.7% vs. 12.9%; gastrointestinal disease: 16.6% vs. 12.9%; tobacco use: 3.2% vs. 2.5%; baseline MRI: 57.9% vs. 58.9%; and baseline relapse: 22.7% vs. 19.9%, respectively.

Table 1. Baseline demographic characteristics for employees with MS with and without suboptimal year-1 outcomes.

Table 2. Baseline clinical characteristics for employees with MS with and without suboptimal year-1 outcomes.

Direct and indirect costs

Employees with MS with vs. without suboptimal year-1 outcomes had higher all-cause medical ($12,730 vs. $6,428; p < 0.0001), non-DMT pharmacy ($2,920 vs. $2,169; p = 0.0199), sick leave ($1,247 vs. $908; p = 0.0274), and short-term disability ($934 vs. $146; p = 0.0001) costs, respectively. Long-term disability ($751 vs. $0; p = 0.1250) and Workers’ Compensation ($56 vs. $24; p = 0.1276) costs did not differ significantly. Direct costs were $7,054 higher ($15,651 vs. $8,597) and indirect costs were $1,910 higher ($2,988 vs. $1,078) in patients with vs. without suboptimal year-1 outcomes. Overall total health benefit costs were $8,963 higher ($18,639 vs. $9,676) in employees with MS with vs. without suboptimal year-1 outcomes ().

Discussion

This real-world study of US employer data sought to quantify the proportion of employees with MS treated with injectable and oral DMTs who had suboptimal year-1 outcomes and to understand the direct and indirect costs associated with them. Half of the employees with MS in this study (50.6%) had suboptimal year-1 outcomes, which were associated with higher medical, sick leave, and short-term disability costs. Previous studies have shown an association between increased disability and higher costsCitation21 and that DMT treatment strategies that improve adherence and persistence or reduce relapse may result in less disability and lower costsCitation14,Citation15. A recent study of patients in Denmark demonstrated that a clinically stable disease course was associated with a reduced risk of losing income from salaries and disability pension compared with those that did not have a clinically stable disease courseCitation22. Studies in other therapeutic areas showed that simpler and less frequent dosing led to greater adherence than more frequent administrationCitation23–25.

The current study is unique in that it provided primary data on the indirect costs of MS, which are not readily available and are not commonly evaluated, particularly in the US. In order to evaluate the cumulative overall impact of suboptimal DMT year-1 outcomes in employees with MS, a composite measure of relapse and treatment adherence, persistence, and switching was used as a measurement of DMT performance and to define a patient population at risk of future disability and unemployment. Similar to our study, a recent investigation used a composite measure – defined as treatment discontinuation and/or MS relapse – in evaluating the time to DMT treatment failure in a cohort of patients on oral therapiesCitation26. By combining measures of disease outcomes into a composite endpoint, measurement of the overall effect of treatment may be simplified for clinically meaningful interpretationCitation27. These techniques, such as NEDA-3 (absence of relapses, MRI activity, and confirmed disability worsening), have already been used extensively in the MS scientific literature as important primary and secondary endpoints.

The findings of the current study are consistent with a prior study by Parise et al.Citation28 that evaluated the direct and indirect cost burden associated with relapses of different severities using a US insurance claims and employee disability database (1999–2011). Among employees with MS (total n = 9,421; no relapse n = 7,686; low/moderate severity relapse n = 1,220; high severity relapse n = 515), annual incremental direct costs were higher for those with low/moderate severity relapse ($8,269 [95% confidence interval (CI) = $6,565–$10,115]) and those with high severity relapse ($24,180 [95% CI = $20,263–$28,482]) compared to those without a relapse. A similar relationship was seen in evaluating indirect costs (low/moderate severity relapse cohort = $1,429 [95% CI = $759–$2,147] and high severity cohort = $2,714 [95% CI = $1,468–$4,035] vs. no relapse cohort). There was also a greater cost burden for caregivers of patients with more frequent relapses vs. no relapses (direct and indirect = $1,725 [95% CI = $376–$2,885]), but this relationship was not observed in those with less frequent relapses.

The current study also reinforces that MS is a chronic and debilitating disease that poses a substantial employer burden in terms of medical, absenteeism, and disability costs. Differences in cost between employees with MS vs. non-MS controls and between treated and untreated employees with MS were previously reported. A study by Ivanova et al.Citation9 showed that employees with MS had significantly higher rates of physical, mental health, and other neurological disorders, and more than 4-times greater indirect costs compared to employee controls. Previous studies also demonstrated that use of DMTs in employees with MS was associated with lower rates of relapses and substantial medical and indirect cost savingsCitation9,Citation14,Citation16,Citation29.

There are several limitations of the current study. The ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM codes used for identifying patients with MS in the administrative claims analysis do not distinguish between different disease courses (i.e. relapsing-remitting and secondary progressive MS), and therefore we were unable to determine the distribution of patients by disease subtypes. Potential limitations of administrative data include the risk of clerical inaccuracies, recording bias secondary to financial incentives, and temporal changes in billing codes. The analysis was also restricted to data available in a health claims database, and other unmeasured factors may have confounded the observed relationships (e.g. clinician-reported relapses and MRI data). Additionally, the association between suboptimal year-1 outcomes and costs may not be causal. While adherence to DMT was assessed based on dispensed prescriptions, it is unknown whether the employees actually took their medications. Further, relapses were determined by a validated algorithm used for administrative claims dataCitation18,Citation19. In this context, relapses may have been underestimated, as only relapses requiring an outpatient visit with steroid use, ER visit, or inpatient stay were captured.

These administrative claims data were derived from US employees with MS with commercial health insurance and, therefore, may not be generalizable to US patients with MS who are (1) unemployed, or (2) employed but do not have health insurance benefits from their employers. The results also may not be generalizable to patients in other countries given the potential variability in patients, healthcare practice patterns, and healthcare delivery organizationsCitation30. The study focused on first DMT in an effort to include a more homogenous sample of patients because of the chronicity and complexity of MS. The 6-month baseline period was selected in order to maximize the number of patients available for analysis; however, a longer baseline period of up to 12 months would be preferred for future analyses as more patient data accumulate. Patients may have received MS diagnoses and DMTs prior to inclusion in this dataset. These findings may not be generalizable to patients who have had previous DMTs. Also, these results cannot be generalized to patients initiating infusion therapies since these treatments were not included in the current investigation.

There were additional shortcomings to the current study. We were unable to assess the direct relationship between the individual components of the suboptimal year-1 outcome definition (e.g. relapse, non-adherence, etc.) and employment based on the sample size available for analysis. Also, the study was not powered to evaluate the comparative effects of individual DMTs or the impact of the level of DMT efficacy (e.g. low, moderate, high) on clinical and economic outcomes due to the limited amount of employer data available. It is expected that the type of DMT may affect treatment outcomes based on previous analysesCitation31–34. Future studies may offer a better understanding of the direct effects of treatment on various economic outcomes.

Conclusion

This real-world, health claims database study showed that half of employees demonstrated suboptimal year-1 outcomes in the first year of injectable and oral DMT treatment. Further, suboptimal year-1 outcomes were associated with higher medical, sick leave, and short-term disability costs in employees with MS. In this context, a better understanding of the relationship between suboptimal year-1 outcomes and their impact on direct and indirect costs is important for optimizing long-term care for employees with MS. DMT treatment strategies that improve adherence and persistence or reduce relapses may result in less patient disability and lower payer and employer costs. Further, evaluation of the direct relationship between the individual components of the suboptimal year-1 outcome definition (e.g. relapse, non-adherence, etc.) and employment and the impact of individual DMTs would be important areas of future research.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation of data, manuscript development, and article publication were financially supported by EMD Serono, Inc., Rockland, MA, USA, an affiliate of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany. The authors had full control of the manuscript and provided their final approval of all content.

Declaration of financial/other interests

CMH received funding support from EMD Serono, Inc. RAB is an employee of Better Health Worldwide, Inc. IAB and NJR are employees of Workpartners LLC. Better Health Worldwide, Inc. and Workpartners LLC received funding from EMD Serono, Inc. to run the analysis. LL and ALP are employees of EMD Serono, Inc., Rockland, MA, USA, an affiliate of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany. CH is an employee of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany.

A peer reviewer on this manuscript has disclosed that they have consulted for EMD Serono among other MS pharmaceutical companies. The peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Previous presentation

Hersh C, Brook R, Rohrbacker N, Beren I, Lebson L, Henke C, Phillips A. Economic Burden of Multiple Sclerosis in Employees with and without Suboptimal Treatment Outcomes to Disease-Modifying Drugs: An Employer Perspective. Presented at American Academy Neurology (AAN) Annual Meeting; Virtual; April 25–May 1, 2020.

Supplemental Material

Download ()Acknowledgements

The authors thank Nathan L. Kleinman, PhD of Workpartners [Cheyenne, WY] for comments on the draft and interpretation of the results and Natalie C. Edwards, MSc of Health Services Consulting Corporation for drafting the manuscript. Writing and editorial support for the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Jenna Steere, PhD, Erich Junge, and Phoebe Sadler of Ashfield MedComms (New York, NY).

Data availability statement

The data utilized for this study were obtained through a license agreement with Workpartners.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

i Formally known as Human Capital Management Services (HCMS).

References

- Lublin FD, Reingold SC, Cohen JA, et al. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: the 2013 revisions. Neurology. 2014;83(3):278–286.

- Marrie RA. Comorbidity in multiple sclerosis: implications for patient care. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13(6):375–382.

- Krause I, Kern S, Horntrich A, et al. Employment status in multiple sclerosis: impact of disease-specific and non-disease-specific factors. Mult Scler. 2013;19(13):1792–1799.

- Moore P, Harding KE, Clarkson H, et al. Demographic and clinical factors associated with changes in employment in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2013;19(12):1647–1654.

- Kobelt G, Thompson A, Berg J, et al. New insights into the burden and costs of multiple sclerosis in Europe. Mult Scler. 2017;23(8):1123–1136.

- Paltamaa J, Sarasoja T, Wikstrom J, et al. Physical functioning in multiple sclerosis: a population-based study in central Finland. J Rehabil Med. 2006;38(6):339–345.

- O’Connor RJ, Cano SJ, Ramió I Torrentà L, et al. Factors influencing work retention for people with multiple sclerosis: cross-sectional studies using qualitative and quantitative methods. J Neurol. 2005;252(8):892–896.

- Pack TG, Szirony GM, Kushner JD, et al. Quality of life and employment in persons with multiple sclerosis. Work. 2014;49(2):281–287.

- Ivanova JI, Birnbaum HG, Samuels S, et al. The cost of disability and medically related absenteeism among employees with multiple sclerosis in the US. Pharmacoeconomics. 2009;27(8):681–691.

- Lad SP, Chapman CH, Vaninetti M, et al. Socioeconomic trends in hospitalization for multiple sclerosis. Neuroepidemiology. 2010;35(2):93–99.

- Nicholas JA, Electricwala B, Lee LK, et al. Burden of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis on workers in the US: a cross-sectional analysis of survey data. BMC Neurol. 2019;19(1):258.

- Confavreux C, Vukusic S. The clinical course of multiple sclerosis. Handb Clin Neurol. 2014;122:343–369.

- Salter A, Thomas N, Tyry T, et al. Employment and absenteeism in working-age persons with multiple sclerosis. J Med Econ. 2017;20(5):493–502.

- Ivanova JI, Bergman RE, Birnbaum HG, et al. Impact of medication adherence to disease-modifying drugs on severe relapse, and direct and indirect costs among employees with multiple sclerosis in the US. J Med Econ. 2012;15(3):601–609.

- Yermakov S, Davis M, Calnan M, et al. Impact of increasing adherence to disease-modifying therapies on healthcare resource utilization and direct medical and indirect work loss costs for patients with multiple sclerosis. J Med Econ. 2015;18(9):711–720.

- Birnbaum HG, Ivanova JI, Samuels S, et al. Economic impact of multiple sclerosis disease-modifying drugs in an employed population: direct and indirect costs. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25(4):869–877.

- Rajagopalan K, Brook RA, Beren IA, et al. Comparing costs and absences for multiple sclerosis among US employees: pre- and post-treatment initiation. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(1):179–188.

- Chastek BJ, Oleen-Burkey M, Lopez-Bresnahan MV. Medical chart validation of an algorithm for identifying multiple sclerosis relapse in healthcare claims. J Med Econ. 2010;13(4):618–625.

- Capkun G, Lahoz R, Verdun E, et al. Expanding the use of administrative claims databases in conducting clinical real-world evidence studies in multiple sclerosis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2015;31(5):1029–1039.

- Marrie RA, Cohen J, Stuve O, et al. A systematic review of the incidence and prevalence of comorbidity in multiple sclerosis: overview. Mult Scler. 2015;21(3):263–281.

- Moccia M, Palladino R, Lanzillo R, et al. Predictors of the 10-year direct costs for treating multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand. 2017;135(5):522–528.

- Chalmer TA, Buron M, Illes Z, et al. Clinically stable disease is associated with a lower risk of both income loss and disability pension for patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020;91(1):67–74.

- Coleman CI, Limone B, Sobieraj DM, et al. Dosing frequency and medication adherence in chronic disease. J Manag Care Pharm. 2012;18(7):527–539.

- Saini SD, Schoenfeld P, Kaulback K, et al. Effect of medication dosing frequency on adherence in chronic diseases. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15(6):e22–33.

- Patti F. Optimizing the benefit of multiple sclerosis therapy: the importance of treatment adherence. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2010;4:1–9.

- Vieira MC, Conway D, Cox GM, et al. Time to treatment failure following initiation of fingolimod versus teriflunomide for multiple sclerosis: a retrospective US claims study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2020;36(2):261–270.

- Irony TZ. The "utility" in composite outcome measures: measuring what is important to patients. JAMA. 2017;318(18):1820–1821.

- Parise H, Laliberte F, Lefebvre P, et al. Direct and indirect cost burden associated with multiple sclerosis relapses: excess costs of persons with MS and their spouse caregivers. J Neurol Sci. 2013;330(1–2):71–77.

- Birnbaum HG, Leong SA, Oster EF, et al. Cost of stress urinary incontinence: a claims data analysis. Pharmacoeconomics. 2004;22(2):95–105.

- Moccia M, Tajani A, Acampora R, et al. Healthcare resource utilization and costs for multiple sclerosis management in the Campania region of Italy: comparison between centre-based and local service healthcare delivery. PLoS One. 2019;14(9):e0222012.

- Moccia M, Loperto I, Lanzillo R, et al. Persistence, adherence, healthcare resource utilisation and costs for interferon Beta in multiple sclerosis: a population-based study in the Campania region (southern Italy). BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):797.

- Lucchetta RC, Tonin FS, Borba HHL, et al. Disease-modifying therapies for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a network meta-analysis. CNS Drugs. 2018;32(9):813–826.

- Siddiqui MK, Khurana IS, Budhia S, et al. Systematic literature review and network meta-analysis of cladribine tablets versus alternative disease-modifying treatments for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34(8):1361–1371.

- McCool R, Wilson K, Arber M, et al. Systematic review and network meta-analysis comparing ocrelizumab with other treatments for relapsing multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;29:55–61.