Abstract

Aim

The pharmaceutical or drug supply chain is the means through which prescription medicines are manufactured, stocked, and delivered to consumers. How the complexity and fragmentation of this supply chain shape or reshape the decisions and courses of action as well as risk aversions of its actors (stakeholders) is the question we address in reviewing recent literature presented at the 2021 AEA-ASSA economics convention. In doing so, we identify key aspects or dimensions of the supply chain that remain unexplored or under-explored in the empirical literature.

Approach

All original research relevant to the pharmaceutical supply chain were selected from the AEA-ASSA convention panel sessions. Empirical evidence was thematically identified, and the theoretical and practical implications of findings on firm and stakeholder decision-making were analyzed.

Findings

Stakeholder choices and risks in the action steps or stages of the supply chain are conditioned or framed by variables that are less prominent and seldom documented in the empirical literature. These include firm ownership and marketing, the provider’s IT system, pricing and discounts negotiated by pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), health insurance coverage, employer plan sponsorship, and hassle costs of drug prescribing and monitoring. On the other hand, prominent and well documented policy initiatives, like international reference pricing and renationalization or “decoupling” from global value chains, can have unintended effects on supply chain actors and end-users, including reverse redistribution. The continuing and changing multi-dimensional character of the supply chain adds to its complexity and fragmentation

Conclusions

Organizational, operational, and value-adding measures to overhaul the drug supply chain and make it perform better have been proposed in the surveyed literature and elsewhere. Yet, aspects of the supply chain that bear a direct impact on firm short-term financial success typically assume precedence in evaluations of performance and effectiveness. Whether and to what extent the drug supply chain will change to cope and adapt to the major challenges and upheavals it currently faces are lingering questions.

Introduction

The pharmaceutical or drug supply chain is the means through which prescription medicines are manufactured, stocked, and delivered to consumers as end-users. It encompasses all organizational, operational, and value-adding elements and activities needed to produce a drug and get it to the consumer, starting with its development and testingCitation1. Much of the current complexity and fragmentation of the supply chain network derives from its wide range of actors (stakeholders), a series of interrelated action steps or phases to make medicines available and accessible, and the ensuing risk aversions of actors since stakes are high and multi-dimensional, involving firm profit, patient and public health, product satisfaction, firm reputation and liability. Actors, actions, and aversions in the pharmaceutical supply chain can also be studied in terms of the R&D-intensive cost structure and rapid technological change that characterize the drug industry itself, and underpin product innovation, pricing, and diffusion in the supply chain.

The key stakeholders in the drug supply chain are the pharmaceutical companies (drug manufacturers), wholesale distributors, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), pharmacies – whether retail pharmacies (which typically handle short-term illnesses), specialty pharmacies (focused on complex and chronic conditions that require more hands-on care), mail order and online pharmacies, etc. – and, of course, the consumers. In many instances, physician offices form part of this chain to whom wholesalers transfer medications and from which patients may buy them directlyCitation2. Although there are slight variations from country to country, and at times from product to product, there are essentially five basic steps or stages in the drug supply chain, as illustrated belowCitation1:

Pharmaceutical companies: manufacturing sites of these firms serve as point of origin for any drug product, with drug pricing and marketing decided by the drug maker based on expected demand, market competition, and marketing costs for establishing wholesale acquisition cost.

Wholesale distributors: drugs are purchased from the manufacturers by wholesalers for distribution to pharmacies and other customers (e.g. physician offices, hospitals and hospital chains, and some health insurance carriers).

PBMs: serve as middle-men between drug manufacturers and payers by determining which drugs will be paid for, the quantity that will be supplied to a pharmacy and other receiving firms, and the amount consumers pay out-of-pocket when the prescription is filled based on the rebates and other discounts that PBMs negotiate with manufacturers and health insurers.

Pharmacies: retail, specialty, mail-order/online, and other types of pharmacies purchase directly from manufacturers or indirectly through wholesalers, maintain ample stock of the medication, and provide drug safety and efficacy information to consumers (physician offices, hospitals and hospital chains, etc. might assume these functions in lieu of pharmacies).

Consumers: after a drug has gone through the preceding steps or stages, and is ready to be dispensed, patients and other consumers purchase them from a pharmacy, and sometimes from a physician’s office, hospital chain, health plan, etc., based on a prescription issued by their physician.

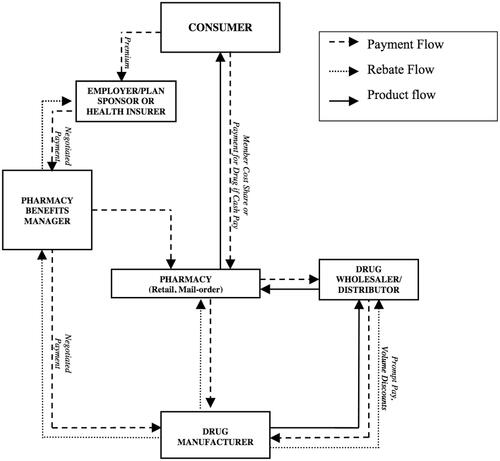

Actors (stakeholders) in the pharmaceutical supply chain in the United States and many other countries face many challenges. Their responses vary depending on their risk aversions and risk management approaches and strategies, especially relative to product, rebate, and payment flows (see ). Their responses affect and are conditioned or framed by organizational, operational, and value-adding elements or dimensions of the supply chain. These include the healthcare provider’s IT system, drug marketing and promotion, the patient’s prescription drug insurance coverage, and price-setting negotiations, among others. While often understudied, they are equally important to the cost-calculus of supply chain actors and bear spillover or unintended consequences.

Figure 1. Key actors in the pharmaceutical supply chainCitation1 (p. 3).

Among others, challenges to the supply chain involve its visibility and effectiveness, R&D investment costs in drug development and testing, drug prominence, drug counterfeiting and diversion, cold-chain shipping issues, fast and continuously rising drug prices, and increased (if not confusing) government regulation, all of which can significantly add up to the patient’s out-of-pocket costsCitation1,Citation2. Several of these challenges, notably R&D costs, price increases and control, drug prominence, drug diversion and misuse, and drug monitoring regulation, were addressed during the 2021 AEA-ASSA economics conventionFootnotei. Originally scheduled to be held in Chicago, this turned into a virtual convention owing to the exigencies created by the covid-19 pandemic. It nonetheless produced 27 panel sessions devoted to health and medical economics, each featuring three to five presentations of original and creative research. Panel sessions on covid-19, followed by the opioid crisis, dominated these health and medical economics sessions. One major theme we gathered from several paper presentations focused on the drug supply chain, particularly its stakeholders, their choices and courses of action, and their risk aversions in decision-making at the micro (firm) level.

This paper reviews the theoretical and practical contributions of this recent corpus of research to pharmacoeconomics, particularly elements and aspects of the drug supply chain that remain unexplored or less explored in the empirical literature. In doing so, we identify new terrains in drug production, marketing, and delivery charted by the 2021 economics convention. Collectively, these call for increased attention to their implications on firm decision-making as well as public policy.

Approach

Space limitations confine this literature review to all original research papers pertinent to the drug supply chain which were presented at the 2021 AEA-ASSA convention. These papers were identified and gathered from the following panel sessions: Private and Social Returns to R&D and Vaccine Development; Biases and Conflicts of Interest in Research; Entrepreneurial Finance/Venture Capital; Competition and Pricing in the Retail Pharmacy Market; Economics of Marijuana and Opioids; Empirical Studies of Negotiation and Bargaining Markets; and COVID-19 and Supply Chains. To these selections we added one poster presentation on herd behavior given its implications on R&D investments in drug production.

In consideration of this journal’s objective to promote discussion on broader policy, practice, and resource utilization issues, this review will encompass: (1) new and emerging themes as well as variations in the study of the pharmaceutical supply chain; (2) pharmacoeconomic challenges from unexplored – or seldom explored – aspects or dimensions of the supply chain; and (3) by way of conclusion, the insights and implications on healthcare decision-making and risk management, particularly at the firm level, that may be gathered from this recent literature.

Drug development: choices, biases, and conflicts of interest

Clinical trials by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are prime determinants of drug approvals and influences on prescription decisions. One panel session constituted for the 2021 convention specifically addressed issues of bias and conflict of interest in drug production in light of the growing trend among drug manufacturers choosing to fund clinical trials, a role typically assumed by the public sector. Funder-manufacturers now account for a substantial share of total R&D investments in the United States.

From an R&D standpoint, Benmelech et al.Citation3 discovered that most firm investments are geared towards treating diseases that afflict elderly patients (“targeting”). In combining firm-level R&D data with data on drug development, the authors report that clinical trials’ share of new drug candidates to treat seniors has risen from 20% in the 1980s to well over 40% by 2018. Meanwhile, R&D investments by Big Pharma fluctuated between $80 billion and $100 billion per year (in 2012 dollars) between 2015 and 2018, with Merck, Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson, and a few others among the top R&D spenders worldwide. These suggest that demographic changes (i.e. population aging and increased disabled populations), combined with improvements in average life expectancy, have driven a wedge between private and social returns to investments in drug development. This study highlights transformational and entrenching drug supply patterns, as pharmaceutical firms channel R&D investments and marketing initiatives toward a fast growing segment of the end-user population in the supply chain.

From the standpoint of drug testing, randomized control trials (RCTs) by the FDA remain the primary means of evaluating new drug safety and efficacy. When published in peer-reviewed journals, RCT results not only provide a scientific basis for treatment decisions, but also enable governments and health insurers to develop sound reimbursement policiesCitation4. Oostrom’s studyCitation5 estimated the effect of pharmaceutical firm financial sponsorship on clinical efficacy, leveraging the insight that the same sets of drugs are often compared in different RCTs conducted by parties with different vested financial interests. Theoretically, RCTs that compare the same drugs should be expected to generate comparable estimates, regardless of the interests of the RCT’s funders. Oostrom used newly assembled data on psychiatric RCTs and estimated that a drug is about 0.15 standard deviations more effective when the RCT is sponsored by the drug maker, in contrast to the same drug in the same trial without the drug maker’s participation. On the other hand, observable characteristics of trial design and patient enrollment explain little of this effect. Sponsored studies with non-positive results are likely to be unpublished. But “back-of-the-envelope” risk calculations suggest that almost 50 percent of the sponsorship effect is accounted for by this publication mechanism. As pre-registration requirements are met, the effect decreases over time. Nonetheless, pre-registration seems to work in overcoming sponsorship bias.

Further to the drug testing phase, another study looked into FDA advisory and expert committees which deliberate and vote on yes-or-no questions about new drug applications. NewhamCitation6 found that sequential voting tends to sway or “herd” half of the members who take vote history (i.e. preceding votes) into consideration. The implication is that herd behavior risk compromising information that is aggregated and contained in the vote. For these reasons, FDA-style simultaneous (electronic) voting is suggested by the author in lieu of sequential voting on drug applications and testing.

Li, Liu, and TaylorCitation7 bring in a different dimension into the drug manufacturing stage by investigating the role of venture capital and risk aversions emanating therefrom. Using evidence from pharmaceutical start-ups, where common ownership is widespread, their study reports that common ownership leads venture capitalists to stifle competition among start-ups, except in limited circumstances. The study examined how a start-up responds after seeing a competitor firm make progress on a related drug project. If the two start-ups share a common venture capital, the lagging start-up is less likely to advance its own project and obtain venture capital funding. The result is reduced competition between the two start-ups. However, as the authors point out, the risk of anti-competitive effects are usually limited to concentrated product markets, technologically similar projects, early stage projects, and venture capitalists with larger equity stakes and less-diversified portfolios.

Gains and costs in the retail pharmacy market

Kakani, Chernew, and ChandraCitation8 analyzed the drivers of drug spending growth in the U.S. over a ten-year period (2009–2019). The authors used decomposition methods to segregate the differences in a distributional statistic between two groups (or their changes over time)Citation9. They concentrated on drivers among brand-name drugs sold in retail pharmacies. They found that these drivers have turned increasingly sensitive to the use of drug list prices, in contrast to net prices. The list (asking) price – akin to the hospital chargemasterCitation10 – is the “sticker price” of the drug manufacturer based on projected market value or “what the market is likely to bear.” The list price tends to be artificially high or inflated (i.e. unrelated to production cost) because manufacturers usually consider it only as a starting point for negotiating a variety of discounts and other price concessions with buyers (e.g. insurers).

Putting these in a pricing context illuminates the findings of this study. The interactions between three actors in the drug supply chain – the manufacturer, insurer, and PBM – can aggressively drive up the cost of a prescription drug, particularly in the absence of government pricing regulation, which is the case in the USCitation11. For one, that leaves drug firms to select their list prices depending on the market competition and how effective or novel is the treatment their drugs offer. Wholesalers, mostly national firms, will pay manufacturers based on or close to the list price, and then supply the drug to pharmacies, dispensaries, doctor’s offices, hospitals and hospital chains, etc. But consumer demand for the drug will be mostly absent (to the detriment of the drug maker) if the insurer did not approve the drug and included it in its formulary. This is where the PBM comes in as middle-man between the manufacturer and insurer. The PBM negotiates and bargains with both parties to get the drug listed, set its price, and qualify it for rebates and other discounts. But “[n]ot only do PBMs wrangle rebates and discounts from the manufacturers in exchange for getting their drugs placed on the insurance companies’ formularies, they also help determine where on the formulary hierarchy any drug will be”Citation11. In turn, the manufacturer will have to pay the PBM a fee for its transaction costs (of bargaining, negotiated drug pricing, formulary risk reduction, etc.). This fee takes the form of a rebate that discounts the manufacturer’s drug list price by a certain amount or percentage (see ).

At this point, the PBM could do either one of two things with the manufacturer’s rebate: It could take a flat dollar amount from or percentage share of the rebate, and pass the rest of the savings to the employer offering health insurance to its employees, or the PBM may simply raise the fee it charges the insurance company for its transaction costsCitation11. Either way, the drug net price, post-rebate, represents what the manufacturer makes on the sale. For their part, the insured consumer or patient pays the pharmacy either a fixed copayment or a fraction of the full list price, depending on their insurance plan’s cost-sharing terms. Consumer out-of-pocket costs might be reduced by coupons and other price discounts that the manufacturer distributes through physicians and the Internet to increase firm and/or drug name-recall and consumer demand. How a drug rebate or discount is negotiated is therefore equally complicated and fragmented. And it is essentially proprietary in character, based on the actions and aversions of the manufacturer, insurer, and PBM.

Against this backdrop, the study by Kakani, Chernew, and ChandraCitation8 uncovered a two-directional path in drug spending growth. When list prices are used, list price growth is the prime explanatory variable in spending growth. But when rebates are factored into the equation, new drug (product) entry into the pharmaceutical market is the most important factor in explaining spending growth. Annual list price inflation was 11 percent during the 10-year period under study, while net price inflation was low at only 2 percent. In the last five years (2014–2019), net prices, in fact, declined by 1 percent annually. It was even shown to have contributed to negative spending growth.

What effects – direct or indirect – might a provider IT system have on the supply chain, especially in terms of prescriptive choices and risk calculations? In addressing this question, Munk-Nielsen and HauschultzCitation12 looked into product prominence in terms of equilibrium prices and market shares. The authors relied on a dataset that covered all transactions and prices in Danish pharmacies over an 11-year period (2005–2016). Prominence arises in this case because prescribing physicians “use a search engine to find drugs which presents results in alphabetical order. This generates arbitrary variation in brand prominence for physicians across products, which [the authors] use to estimate its effect on prescription shares, market shares, and prices”Citation12 (p. 2).

The study found that alphabetical rank is crucial in determining which medication doctors are likely to put on their prescription (i.e., the indirect marketing effect). “Brand ranking” is important in Denmark (and several other countries featuring a variant of this system) because of the design of the search tool in the doctors’ IT system. When they type in a query (e.g. “Omeprazole”), packages with a name matching the search term automatically appear in alphabetical order by package name (note: the ability of firms to change the product name is limited by Danish regulation). To obtain price information, the doctor clicks on the product.

Moreover, this study found that drug prescriptions, prices, market shares, and revenue decrease in alphabetical rank. The final choice is made by the customer who pays for the product. But the customer receives a fraction of the cheapest price in subsidy since s/he brings the doctor’s prescription to the pharmacy to do an ordered search with assistance from the pharmacist who is legally required to recommend the cheapest available product (“generic substitution”). In addition, doctors tend to increase their search initiatives for low-income and female patients, suggesting some redistributive effect from the search process.

Hence, this study's bottom-line contribution is to demonstrate why a doctor’s costly effort involved in browsing through the list of available brands, and trading off search costs against expected savings to the consumer, generate strong effects on end-user drug choices, and ultimately, drug prices. This study calls attention to the under-explored role of the doctor in driving drug demand. It also sheds light on market positioning or the competitive advantages that enable a firm brand name or product to gain prominence (over competitors) through online searches.

The work of Janssen and ZhangCitation13 on retail pharmacies and drug diversion exemplifies the heightened interest in the medical economics of opioids. As of 2017 alone, 11.4 million Americans were reported to have misused opioids, including 11.1 million who misused prescription drugsCitation14 and an average of 130 Americans dying every day from an opioid overdoseCitation15.

Legally prescribed opiod analgesics are often the gateway to addiction. Janssen and Zhang chose to analyze the roles assumed by pharmacies in the supply chain using a firm (ownership) approach to compare independently owned pharmacies' with chain pharmacies in the U.S. from 2006 to 2012. Independently owned pharmacies were found on average to dispense about 41% more opioids and 62% more OxyContin compared to their chain pharmacy counterparts. However, after its acquisition by a drug chain, a previously independent pharmacy drastically reduces opioid dispensation by as much as 32% and OxyContin by 43%. OxyContin’s reformulation, for example, was shown to reduce opioid demand for diversion (i.e. illegal procurement and recreational use), but not demand for medical uses. Half of the difference in dispensed OxyContin doses by independent and chain pharmacies was attributed by the study to drug diversion. OxyContin dispensation by independent pharmacies also appears to be higher in areas with greater pharmacy competition.

The authors account for the greater likelihood that independent pharmacies will be linked to drug diversion in two ways. One, they have stronger financial incentives due to lower expected risk and cost of wrongdoing. Second, they may have less information on patients' prescription drug use history. While prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs) might reduce the information asymmetry between independent and chain pharmacies to some extent, the authors suggest that monitoring of small, independent pharmacies be improved. Being “the last line of defense ensuring that prescriptions are filled and drugs dispensed only for legitimate medical use, pharmacies play an important role in all four … diversion channels [reported by the study]”Citation15 (p. 2), namely doctor-shopping, prescription theft or forgery, health insurance fraud, and pharmacy thefts and robberies.

Enhanced prescription monitoring was similarly suggested by Jacobson, Alpert, DykstraCitation16, albeit by way of interventions aimed at physician prescribing practices to contain abuse by end-users in the opiod supply chain and by retail pharmacies on the supplier sideCitation17,Citation18. PDMPs are data-heavy technological platforms that can track both prescriber and patient habits. States that mandatorily use PDMPs require doctors to query the patient’s prescription history through the program before prescribing any controlled substances. There are two possible outcomes. One is that PDMPs will generate information gains that decrease prescribing to patients suspected of misuse and diversion when information on opioid prescription histories become available. The other is that PDMPs could unintentionally create hassle costs that reduce the rate of opioid prescribing to all patients, including those who would truly benefit from its legitimate, medical uses. This occurs as another hurdle (“chilling effect”) in the form of required record checks is introduced by PDMPs for issuing opioid prescriptions.

Using individual-level claims data from one user-state (Kentucky, whose landmark PDMP drastically reduced opioid prescribing), the authors isolated the extent to which prescribing reductions from PDMPs are due to information gains rather than hassle costs, and the long-term consequences of the prescribing changes. While conceding that information gains have beneficial impact, the authors found that hassle costs account for the majority of prescribing decline across the board. Thus, they propose introducing a cost to physicians in prescribing high-risk medications to improve treatment targeting. But whether PDMPs are truly effective is yet to be determined, since use effects remain mixed, net benefits vary by state, and it is not possible to perform a controlled study of their benefitsCitation19.

Bargaining and international reference pricing

Although the supply chain actor studied by Dubois, Gandhi, and VassermanCitation20 is the drug manufacturer, their objective was to assess the viability of international reference pricing in containing rising drug costs in the U.S., which is twice as much per American compared to a European. A similar price control strategy was previously proposed by the Trump administration (2016-2020), which had advocated a “most favored nation” trade clause to contain pricing of Medicare Part B and Part D drugsCitation21. Although the Trump strategy was never implemented, many expected that target prices – traditionally derived from the average sales price of a drug plus a 6 percent add-on payment – would be replaced by a five-year phased international price index to obtain the lowest U.S. price of a drug available in other OECD countries, except in situations where the average sales price is lowerCitation22.

It is in this context that the authors evaluate the effects of a hypothetical U.S. international reference pricing policy that caps drug prices in U.S. markets by prices offered in Canada (an OECD country). Canadian prices are set through a Nash bargaining process between pharmaceutical firms and the federal government. Besides greater drug consumption, more patented drugs, and higher drug prices in the U.S., other sources of price differences between the two countries include local production costs, exchange rates, supply chain organization, market structure, entry, regulation, and willingness-to-pay. The net effect of any reference pricing would be to restrict drug prices in the home country (U.S.) so that they cannot be greater than some multiple of prices in the reference country (Canada). For example, US drug prices ≤ Canadian prices or ≤ product investment cost, I(pj).

Based on a structural price determination (supply-and-demand) model for the two countries, the authors found that reference pricing policy is likely to yield the following outcomes: (1) A slight decrease in US drug prices (-1.9%), but a substantial increase in Canadian prices (up to 65%) “because firms will internalize the across-country restrictions involved by the US reference pricing”Citation20 (p. 35); (2) Considerable increase in pharmaceutical expenses in Canada (52.4%), but quite stable in the U.S. (-0.6%, with variation over classes); (3) Modest consumer welfare gains in the US (i.e. for some classes), but substantial welfare losses in Canada after the price changes; and (4) Increase in overall pharmaceutical expenses (2.7%) outweighed by (a 5.1%) overall firm profit increase, indicating that reference pricing would in the end constitute a net transfer from consumers to drug companies. While the authors do not directly address it, reference pricing is also bound to create externalities across supply chains and markets that will not only affect U.S. drug prices, but whose global effects are yet unknown. These include long-run policy effects on drug innovation within the supply chain.

Global supply chains amid the Covid-19 pandemic

Three covid-19 studies adopted a macro level, rather than a firm-based, approach to supply chains in general. The forthcoming 2022 AEA-ASSA convention in Boston is expected to generate more covid-19 studies, including those that were unable to make it to the Spring submission deadline for the 2021 convention, possibly yielding more microeconomic work relevant to the drug supply chain.

Globalization has driven attention to international systems of supplier relationships and expansions of supply chains over national boundaries and into other countries and continents. Drug supply chains are not any different. The concept of a global value chain (GVC) for pharmaceuticals has, in fact, been used to analyze international trade based on “the full range of activities that are required to bring a product from its conception, through its design, its sourced raw materials and intermediate inputs, its marketing, its distribution and its support to the final consumer” beyond national bordersCitation23. Yet, there is no gainsaying that GVCs in general have dramatically declined since the worldwide financial crisis that began in 2008. The covid-19 pandemic only added momentum to this ongoing trend by providing a novel rationale for protectionism or “renationalization” in several countries.

T1he study of Pandalai-Nayar et al.Citation24 is a logical starting point from a macro perspective, as it inquires into the role of global supply chains (including pharmaceutical) on the pandemic’s impact on GDP growth. The authors quantified the average real GDP downturn attributed to covid-19 shocks in 64 selected countries (x = 29.6%), and then assessed the fraction of that downturn caused by transmission through global supply chains (≈1/4 of downturn). They also specifically looked into increased demand for health services when sectoral labor supply is restricted by business lockdowns nationwide. The authors conclude that while GDP impacts are heterogeneous and depend on a country’s sectoral composition and role in the supply chain, by and large, “decoupling” from GVCs does not make countries any more resilient to pandemic-induced contractions in labor supply. That is because eliminating reliance on foreign inputs to production in GVCs risk reliance on domestic inputs. These are disrupted to a greater magnitude by lockdowns and cannot help mitigate the size of such contractions. In short, participation in global supply chains does not make economies more vulnerable, but could even help insulate a country from covid-19 shocks on supply chains.

Eppinger et al.Citation25 echo the findings of Pandalai-Nayar et al.Citation24 For their study, Eppinger et al. asked whether countries would be better off by disengaging from GVCs, and building up domestic inputs, to safeguard against foreign shocks during a global public health crisis exemplified by covid-19. Using also a multi-country and multi-sectoral trade model to determine net welfare losses from decoupling and its consequences for international shock transmission, the authors found that shutting down GVCs causes substantial welfare losses in all countries studied and does not justify aversion to (lower) foreign shock exposures. The policy implications for countries currently debating whether to disengage from GVCs are evident from these two papers, particularly as globally interconnected firms are trying to recover from supply chain disruptions caused by the pandemic.

Using Uganda as a country case “for proof of concept,” Carvalho, Elliott, and SprayCitation26 introduced the concept of a supply chain “bottleneck” based on a firm whose removal from an economy-wide production network leads to a sufficiently large fall in aggregate output. In their illustration, supply (e.g. drugs, personal protective equipment) can no longer meet aggregate demand. The authors assert that the firm’s position in the network could make it quite indispensable in the production of specific goods and services. Its comparative advantage is further helped if it is located in industries which have fewer new entrants, thus delimiting market competition. However, the location of these bottlenecks will depend not only on a firm’s immediate connections, but also on the entire structure of the production network. This usually results in bottleneck firms enjoying significantly higher profits, sales, wage bills, and mark-ups even during a global pandemic like covid-19.

Discussion and conclusion

Any literature review in health and medical economics is bound to find new or evolving approaches and perspectives to a given subject or issue. These may compliment or reinforce each other. Others may simply appear disconnected. And there are some that may be outright conflicting. While this literature review is not exempt from such observations, it is evident that important theoretical and practical implications on the pharmaceutical supply chain have been identified in a wide array of papers in health and medical economics presented at the 2021 AEA-ASSA convention. Our task has been to analyze and contrast them for which this review was thematically divided, and where variations exist, to possibly explain or relate them in terms of uncharted or less charted terrains of the sub-field. Yet, continuity is also evident from the drug supply chain.

One insight concerns the continuing and changing multi-dimensional character of the drug supply chain that adds to its complexity and fragmentation. While there are the usual actors and the traditional roles they perform as well the risks they face at each step or stage of the supply chain, there are less studied actors and influences on supply-side decision-making to which the literature under review has called attention. These include the roles and functions performed by IT systems in drug prominence, health insurers in running formularies, PBMs in drug discounting and listing, marketers in information dissemination, employers that sponsor employee health plans, PDMPs in physician prescribing, and firm (pharmacy) ownership in dispensing controlled substances. After all, the supply chain covers every organizational, operational, and value-adding aspect and activity needed to transfer and sell a drug through which it can earn a profit.

The reviewed literature has equally drawn attention to contemporary – and some rather unique – challenges facing the drug supply chain. R&D investment costs, pricing pressures, financial sponsorship effects on clinical testing, herding in expert committee voting, drug prominence in online searches, drug adulteration, counterfeiting, and diversion, drug accessibility to end-users, and renationalization in response to GVCs exemplify these challenges. There are also supply chain challenges bound by time and space, as studies on the covid-19 worldwide pandemic and the opiod crisis in the U.S. demonstrate. That said, these collective challenges are not commonly taken into consideration in metrics for evaluating supply chain performance. Instead, elements and aspects of the drug supply chain that bear direct impact on the short-term, financial health or success of a firm – such as reduced lead times, increased flexibility, and lower production costs – often assume precedence and centrality in these evaluationsCitation27. This has brought about a wide divergence or gap between the actual and perceived capabilities of drug supply chains in the U.S. and elsewhere.

A related insight is that the effectiveness of a drug supply chain can also be gauged based on how well it supports and enhances a firm’s business strategy. Many pharmaceutical companies and retail pharmacies have effectively implemented business strategies using well crafted supply chain practices, starting at the point of drug development and clinical testingCitation27. U.S. pharmacies further illuminate this point. Approximately three in four drug products are purchased in retail pharmacies (by consumers), about half of which are national chains or food stores with an in-house pharmacy. They handle a wide variety of products sold in an even wider variety of packaging. Because retail pharmacies often find it logistically difficult to buy their stock directly from manufacturers, they typically obtain their supply from wholesalers. In this sense, planning, forecasting, financing, procuring, stock maintenance, and marketing strategies can have simultaneous and interrelated effects which firms operating in the drug supply chain have to balance to achieve organizational goals cost-efficiently.

The surveyed literature suggests how the drug supply chain has directly (and indirectly) affected prescription drug pricing. Whether as a result of R&D investments and financial sponsorship on clinical testing, or negotiations between manufacturers, PBMs and insurers, or Big Pharma in contrast to start-up pricing, the variety of actors at each step of the chain and their respective risk aversions (some flowing out of information asymmetries) are among the main reasons drug costs continue to rise. Rebates, for instance, have increased over the past several years, but consumer out-of-pocket costs are also soaringCitation2. That is because, as some of the studies found, what consumers pay for a branded medicine depends on their insurance drug coverage, the size of the plan deductible, and the deal his/her insurer has negotiated with the drug’s manufacturer, most likely through a PBM.

However, there can be significant variance in the decision-making choices and strategies available to supply chain actors, many conditioned or framed by their respective risk calculus. For one, there is substantial variation in the use of prescription drugs from retail pharmacies, including the quality (and quantity) of information and level of services provided by retail pharmacies and the drug prices they charge to consumers. This is relatively uncharted territory into which some of the reviewed studies on the retail pharmacy market inquired. What is not evident – given the existing knowledge gap – is whether local area retail pharmacy market structures affect these outcomes. Hence, even without getting into purely structural and logistical concerns, the inefficiencies associated with the complexity and fragmentation of the drug supply chain equally pose risks and challenges to patients and providers alike.

Finally, the surveyed literature offers suggestions to help overhaul the drug supply chain, which even some of its actors or stakeholders find to be increasingly ineffectiveCitation27,Citation28. These suggestions appear to this author both sustainable and supportive of many earlier proposalsCitation2. These include R&D targeted to more diverse product types and therapies with shorter life-cycles, more efficient wholesaler distributions, new or improved ways for assessing and monitoring patient medication use, increased attention to physician prescribing and prescribing costs, alternative models of pharmacy information dissemination (e.g. generic substitution), and enhancing (rather than decoupling from) foreign inputs and engagements in GVCs during a global public health crisis. There may again be some variance, especially when it comes to feasibility of implementation. Certain areas, like potential government intervention in drug pricing (e.g. by way of price regulation and international reference pricing), can be controversial from a public policy, firm, and supply chain standpoint because they tend to have reverse (or perverse) redistributive and other unintended effects. And the impact of events like covid-19 in reshaping the drug supply chain in the long-run is not (yet) fully known.

Perhaps only time will tell if and how well the drug supply chain will change to cope and adapt to the major challenges and upheavals it currently faces as well as the strategic solutions that have been devised to address them. As the continuing link between the laboratory and the marketplace, it goes without saying that the supply chain of every pharmaceutical firm will need to be fully capable of meeting tomorrow’s consumer needs. And doing so has undoubtedly profound consequences for the way in which the supply chain manufactures, stocks, and distributes its pharmaceutical products amid changing times and climes.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

No funding was received to produce this article.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

The author has no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in, or financial conflict with, the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This may include employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges with thanks the editorial assistance of Sarah Webster. As with any work of this nature, the usual caveat applies.

Notes

i Annual convention of the American Economics Association (AEA), held virtually in conjunction with the Allied Social Sciences Association (ASSA), January 2–6, 2021.

References

- The Health Strategies Consultancy LLC. Follow the pill: understanding the U.S. commercial pharmaceutical supply chain. Menlo Park, CA: The Kaiser Family Foundation; 2005.

- McGrail S. Fundamentals of the pharmaceutical supply chain. PharmaNewsIntelligence; 2020 [cited 2021 Jan 17]. Available from: https://pharmanewsintel.com/news/fundamentals-of-the-pharmaceutical-supply-chain.

- Benmelech E, Eberly J, Papanikolaou D, et al. Private and social returns to R&D: Drug development and demographics. Paper presented at the 2021 virtual annual meeting of the Allied Social Sciences Association (ASSA); 2021, January 5.

- Chopra SS. Industry funding of clinical trials: Benefit or bias? JAMA. 2003;290(1):113–114.

- Oostrom T. Funding of clinical trials and reported drug efficacy. Paper presented at the 2021 virtual annual meeting of the Allied Social Sciences Association (ASSA); 2021, January 5.

- Newham M. Do expert panelists herd? Evidence from FDA committees. Poster presented at the 2021 virtual annual meeting of the Allied Social Sciences Association (ASSA); 2021, January 2–5.

- Li X, Liu T, Taylor L. Do venture capitalists stifle competition? Paper presented at the 2021 virtual annual meeting of the Allied Social Sciences Association (ASSA); 2021, January 5.

- Kakani P, Chernew M, Chandra A. Pharmaceutical prices, rebates, and spending in the U.S.: Evidence from medicines sold in retail pharmacies. Paper presented at the 2021 virtual annual meeting of the Allied Social Sciences Association (ASSA); 2021, January 4.

- Fortin N, Lemieux T, Firpo S. Decomposition methods in economics. NBER Working Paper 16045, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA; 2010 [cited 2021 Jan 11). Available from: https://www.nber.org/papers/w16045.

- Nation GS. III Hospital chargemaster insanity: heeling the healers. Pepperdine Law Review. 2016;43(1):745–784.

- Entis L. Why does medicine cost so much? Here's how drug prices are set. Time; 2019, April 9 [cited 2021 Jan 11]. Available from: https://time.com/5564547/drug-prices-medicine/.

- Munk-Nielsen A, Hauschultz FP. Markups on drop-downs: prominence in pharmaceutical markets. Paper presented at the 2021 virtual annual meeting of the Allied Social Sciences Association (ASSA); 2021, January 4.

- Janssen A, Zhang X. Retail pharmacies and drug diversion during the opioid epidemic. Paper presented at the 2021 virtual annual meeting of the Allied Social Sciences Association (ASSA); 2021, January 4.

- National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2017 National survey on drug use and health. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA); 2018.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. America’s drug overdose epidemic: data to action. Atlanta, GA: CDC; 2019.

- Jacobson M, Alpert AE, Dykstra S.. Hassle costs versus information: How do prescription drug monitoring programs reduce opioid prescribing? Paper presented at the 2021 virtual annual meeting of the Allied Social Sciences Association (ASSA); 2021 January 3.

- Salazar D. Turning the tide: retail pharmacy grapples with the opioid epidemic. Drug Store News; 2018, February 1 [cited Jan 12]. Available from: https://drugstorenews.com/pharmacy/retail-pharmacy-opioid-crisis-response.

- Bach P, Hartung D. Leveraging the role of community pharmacists in the prevention, surveillance, and treatment of opioid use disorders. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2019;14(1):30–11.

- Davis J. Opioid epidemic: why aren't prescription drug monitoring programs more effective? HealthcareITNews; 2018, April 18 [cited 2021 Jan 17]. Available from: https://www.healthcareitnews.com/news/opioid-epidemic-why-arent-prescription-drug-monitoring-programs-more-effective.

- Dubois P, Gandhi A, Vasserman S. Bargaining and international reference pricing in the pharmaceutical industry. Paper presented at the 2021 virtual annual meeting of the Allied Social Sciences Association (ASSA); 2021, January 4.

- United States Congress, House of Representatives 2019. H.R. 3, Lower Drug Costs Now Act of 2019.

- Neumann T, Cubanski J. Most people are unlikely to see drug cost savings from President Trump’s “most favored nation” proposal; 2020 [cited 2021 Jan 17]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/policy-watch/most-people-are-unlikely-to-see-drug-cost-savings-from-president-trumps-most-favored-nation-proposal/.

- Frederick S. Concept & tools: global value chains; 2016 [cited 2021 Jan 19]. Available from: https://globalvaluechains.org/concept-tools.

- Pandalai-Nayar N, Bonadio B, Huo Z, et al. Global supply chains in the pandemic. Paper presented at the 2021 virtual annual meeting of the Allied Social Sciences Association (ASSA); 2021, January 5.

- Eppinger P, Felbermayr G, Krebs O, et al. Cutting global value chains to safeguard against foreign shocks? Paper presented at the 2021 virtual annual meeting of the Allied Social Sciences Association (ASSA); 2021, January 5.

- Carvalho V, Elliott M, Spray J. Supply chain bottlenecks in a pandemic. Paper presented at the 2021 virtual annual meeting of the Allied Social Sciences Association (ASSA); 2021, January 5.

- Singh M. The pharmaceutical supply chain: A diagnosis of the state-of-the-art [master’s thesis]. Boston, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology; 2005.

- PwC. Pharma 2020: supplying the future – which path will you take?; 2011 [cited 2021 Jan 18). Available from: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/pharma-life-sciences/pharma-2020/assets/pharma-2020-supplying-the-future.pdf.