Abstract

Aims: To evaluate the cost-effectiveness of adding prolonged-release (PR)-fampridine to best supportive care (BSC) versus BSC alone for the improvement of walking ability in patients with MS.

Methods: A cost-utility analysis based on a Markov model was developed to model responders and timed 25-foot walk (T25FW) scores, accumulated costs, and quality-adjusted life-years (QALY) in adults with MS and Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) scores between 4 and 7. The analysis was conducted from a Swedish societal perspective.

Results: In the base-case analysis, PR-fampridine plus BSC led to a higher QALY gain than BSC alone. The largest direct cost was professional care provision followed by hospital inpatient stays while the indirect cost was the loss of earnings due to days off work. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for PR-fampridine plus BSC compared with BSC alone was 57,109 Swedish Kronor (kr)/QALY (€5,607/QALY [1 kr = €0.0981762 on 8 April 2021] and $6,675/QALY [1 kr = $0.116890 on 8 April 2021]). All sensitivity analyses performed resulted in ICERs below 500,000 kr (€49,088 and $58,445).

Limitations: Resource use data were not specific to the Swedish market.

Conclusions: PR-fampridine represents a cost-effective treatment for MS-related walking impairment in Sweden, due to improvements in patients’ quality of life and reduced healthcare resource utilization.

Introduction

Walking impairment is common among patients with multiple sclerosis (MS)Citation1,Citation2, with the risk increasing as the disease progressesCitation3, contributing to its considerable humanisticCitation4–7 and economic burdenCitation7–11. There are currently limited options for the treatment of walking impairment in MS, with prolonged-release (PR)-fampridine (FampyraFootnotei) being the only pharmacological therapy approved for this indicationCitation12. Standard care for MS walking impairment may constitute any therapy that could potentially impact or assist with walking impairment, such as walking aids, exercise regimes, physiotherapy and/or spasticity treatments, which together may be regarded as best supportive care (BSC)Citation13. BSC may have some limited effect in reducing walking impairmentCitation14.

Given the limited effect of BSC, two phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials, MS-F203 and MS-F204, were conducted to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of PR-fampridine in improving ambulation in patients with relapsing-remitting, secondary-progressive and primary progressive MS. Both trials met their primary efficacy endpoint of improved timed walk responseCitation15,Citation16. Efficacy and safety of PR-fampridine were also assessed in phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, MOBILE studyCitation17 and the phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled ENHANCE studyCitation18, both of which investigated the broader primary endpoint of clinically meaningful (at least eight-point) improvement in walking ability on the MSWS-12. In both trials, a higher proportion of PR-fampridine-treated patients demonstrated a clinically meaningful improvement in MSWS-12 scores from baseline over a 24-week period than those in the placebo groupCitation17,Citation18.

Previous MS economic analyses assessed the cost-effectiveness of disease-modifying therapies (DMTs), associated with Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) levels and/or relapseCitation19. Since PR-fampridine is not a DMT and has shown an effect on walking, EDSS models are inappropriate. No published economic analyses have previously been designed to specifically assess the cost-effectiveness of treatments for MS-related walking impairment.

The objective of this economic analysis was to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of PR-fampridine plus BSC versus BSC alone for the improvement of walking ability in adult MS patients in Sweden.

A prior version of the economic model presented here, using the same structure and methods, has been used in various national reimbursement submissions. The model was submitted to the Swedish Dental and Pharmaceutical Benefits Agency (Tandvårds-Läkemedelförmånsverket [TLV]) who reviewed the analysis and granted reimbursement to PR-fampridine in October 2018Citation20. The model described here underwent a thorough independent quality check that led to improvements with regards to the data used for long-term extrapolation of clinical trial data.

Methods

Model overview

A cost-utility analysis based on a Markov model was developed to model PR-fampridine treatment responders defined in the model using the 12-item Multiple Sclerosis Walking Scale (MSWS-12), timed 25-foot walk (T25FW) scores, accumulated costs and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) in Swedish patients with MS-related walking impairment. A 20-year time horizon was used in the base-case scenario as agreed with the TLV (Swedish Dental and Pharmaceutical Benefits Agency)Citation20. However, an alternative scenario looked at a 10-year time horizon and a lifetime time horizon to capture all short- and long-term costs and benefits resulting from PR-fampridine treatment. As recommended by Swedish guidelinesCitation21, both effects and costs were discounted at a rate of 3.0%. The analysis was conducted from a societal perspective, which is recommended and considered appropriate to capture all direct and indirect costs associated with MS-related walking impairment. Furthermore, utility decrements were applied to the model to reflect the incidence of adverse events (AEs) and an alternative weighting approach to BSC utilities was explored in a scenario analysis.

Treatment effect in terms of response to treatment and time on treatment was derived from the PR-fampridine clinical trial programCitation15–18.

The modelled patient population matches the ENHANCE phase III study population, which consisted of adult MS patients with EDSS scores between 4 and 7, corresponding to the approved European Medicines Agency (EMA) indication of PR-fampridineCitation12. Accordingly, patients had a mean starting age of 48.9 years, a mean 137 months since diagnosis and 42% were males. Because the model also includes T25FW, which was not measured in the ENHANCE (or MOBILE) trials, this was assumed to be on average 2.1 feet per second, to match the baseline values observed in the MS-F203 and MS-F204 trials. Although the studies were comparable in terms of patient age, disease duration and EDSS, there were slight differences in the proportions of patients with relapsing-remitting MS (MS-F203: 29% placebo, 27% PR-fampridine; MS-F204: 34% placebo, 36% PR-fampridine; ENHANCE: 49% placebo, 53% PR-fampridine) and secondary-progressive MS (MS-F203: 49% placebo, 55% PR-fampridine; MS-F204: 47% placebo, 52% PR-fampridine; ENHANCE: 31% placebo, 30% PR-fampridine). However, the differences were not considered significant enough to preclude their use in the modelCitation15,Citation16.

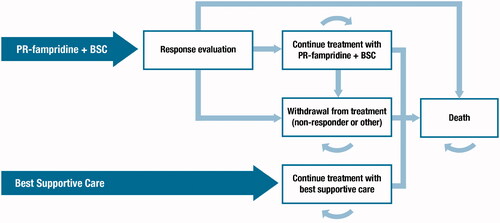

The two-arm Markov model includes two treatment strategies: PR-fampridine and BSC (herein referred to as the PR-fampridine arm), and BSC alone. In this analysis, BSC was used to denote all background supportive care that could be used concomitantly to manage MS symptoms. Because PR-fampridine is added to BSC, BSC is present in both arms of the model, reflecting current treatment practiceCitation13. The recommended dose of PR-fampridine is one 10 mg prolonged-release tablet, twice daily. Patients receiving PR-fampridine start in the “response evaluation” health state until the end of the responder-identification period, which is set at 4 weeks (one cycle) post-treatment initiation, in line with the summary of product characteristicsCitation12. Depending on their response to treatment, patients either “continue treatment with PR-fampridine and BSC”, enter the “withdrawal from treatment” health state, or die, reflecting the patient journey experienced by MS patients. Patients treated with BSC alone can either remain in the “continue treatment with BSC” health state or transition to “death”. Death is an absorbing state in the model, and patients can transition from any health state to the death state at any cycle in the model ().

PR-fampridine responders incur the improved health outcomes associated with treatment response, as reported in the MS-F203, MS-F204, ENHANCE and MOBILE clinical studies, related to increased utility and improved walking ability, and thus, reduced need for care, compared with patients in the “withdrawal from treatment” health state. Once patients withdraw from treatment with PR-fampridine – due to any reason including lack of response to treatment, AEs or other reasons – costs and QALYs are assumed to equal those in the “continue treatment with BSC” health state, reflecting clinical practice. Even though walking speed improvements have been observed upon re-initiation of PR-fampridineCitation22, it was conservatively assumed that once patients withdraw from PR-fampridine treatment they cannot transition back to the “continue treatment with PR-fampridine and BSC” health state and all treatment effects is lost.

Model parameters

Transition probabilities

The treatment response rate was obtained from the ENHANCE clinical trial program (), where the response was defined as a mean improvement on the MSWS-12 score of ≥8 points from baseline over a 24-week treatment periodCitation26. A 5-year retention probability was estimated from pooled MS-F203 EXT and MS-F204 EXT studies for patients responding to PR-fampridineCitation23 and used to estimate the withdrawal probability (for any reason including patients’ perceived lack of treatment effect, the decline in T25FW, and AEs) for each 4-week cycle ().

Table 1. Transition probabilities.

Natural history and treatment effect

There are no long-term clinical trial or resource use data from MSWS-12. Therefore, disease evolution and PR-fampridine treatment effect were defined according to T25FW.

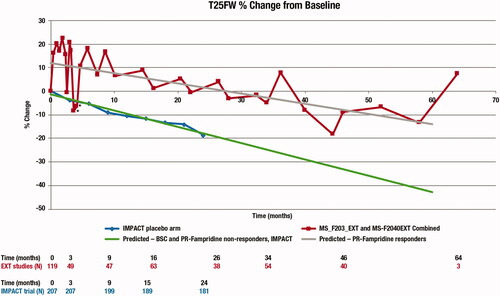

The rate of long-term natural progression of MS with regards to walking speed was obtained from T25FW scores over 24 months that were reported for the placebo arm of the IMPACT trial of interferon beta-1a intramuscular versus placeboCitation27. The IMPACT trial was chosen because it captured T25FW in a population with advanced MS, which closely matches the PR-fampridine population. Choice of this trial can be considered conservative because the placebo arm experienced the slowest published rate of T25FW decline, and therefore likely underestimates the true impact of PR-fampridine. Progression with regards to T25FW for BSC-treated or PR-fampridine treatment withdrawn patients was based on this dataset and then extrapolated beyond the trial’s time horizon using a weighted linear regression ().

Figure 2. Long-term T25FW extrapolated using a linear regression.

*Data points represent time off treatment between the end of the parent trial and the beginning of the extension studies.

Abbreviations. BSC, best supportive care; T25FW, timed 25-foot walk.

For patients who respond to PR-fampridine, results from the two extension studies (MS-F203EXT and MS-F204EXT) were used to model the corresponding progression of T25FW over time, with a weighted linear regression fitted to the pooled data to allow extrapolation beyond the 60-months trial duration. As no data were available regarding the potential sustained treatment effect of PR-fampridine in patients who withdrew from treatment, it was conservatively assumed that these patients lose all treatment effect.

Mortality

PR-fampridine is not associated with a reduced or increased risk of death, therefore the same mortality rate was applied to both armsCitation25. A relative risk of 1.44 for patients with MS compared with the general population was applied to the general mortality probabilities, obtained from 2017 Swedish lifetablesCitation24,Citation25.

Adverse events

AE rates and the costs of non-serious AEs associated with PR-fampridine were taken from the ENHANCE study ()Citation18. Given that the majority of AEs were mild to moderate (serious urinary tract infection or fall each occurred in <1% of PR-fampridine or placebo patients), all AEs were modelled as non-serious. MS relapses were assumed to be unrelated to PR-fampridine treatment and associated with inflammatory disease activity and were therefore excluded from the model. The probability of AEs was incorporated into the model as a per-cycle probability of any AE by first calculating the 26-week risk, then converting it into a 4-week risk by assuming a constant rate.

Table 2. AEs excluding MS relapse observed in the ENHANCE study included in the cost-utility modelCitation18.

Utility data

In the base-case analysis, health state utilities were derived from EuroQoL-5 Dimensions-3 Level (EQ-5D-3L) values from the ENHANCE study (), given that ENHANCE was the largest and longest phase III randomized trial of PR-fampridineCitation28.

Table 3. Utilities based on EQ-5D-3L values from the ENHANCE studyCitation28.

The 3-level version of EQ-5D (no problems, some problems, or unable to/extreme problems) might not be sensitive enough to detect the impact of walking changes on utility given that PR-fampridine is restricted to patients with baseline mobility impairment. In ENHANCE, 82% of PR-fampridine responders reported no change in mobility as measured by EQ-5D-3L from baseline to Week 24Citation28. A greater improvement was observed in MOBILE, likely due to the more sensitive 5-level questionnaire (no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems, and unable to/extreme problems)Citation29. Therefore, utility values from MOBILE (EQ-5D-5L; ) and from a pooled analysis of ENHANCE and MOBILE () were used in alternative scenarios to investigate their impact on cost-effectiveness results. Furthermore, a conservative scenario analysis was conducted in which the utility gains observed in the BSC group were applied to the Responder baseline utility (), to explore the impact of the numerical difference in ENHANCE baseline utilities between treatment arms. The resulting utilities were then applied to the BSC armCitation28,Citation29.

Table 4. Utilities from MOBILE studyCitation30.

Table 5. Utilities from the pooled analysis of ENHANCE and MOBILE studiesCitation17.

Cost data and resource use

Both direct (PR-fampridine drug cost, healthcare professionals, hospitalizations, treatment of AEs, cost of care and modifications/aids) and indirect (absence from work) costs were estimated in the base-case analysis, reflecting the societal perspective in Sweden (). The PR-fampridine drug cost (1,402.85 Swedish Kronor (kr) every 4 weeks (€138 [1 kr = €0.0981762 on 8 April 2021Citation34 and $164 [1 kr = $0.116890 on 8 April 2021Citation34, the same rates have been used in all currency conversions presented) was assigned to all PR-fampridine-treated patients, regardless of response status. Similarly, it was assumed that both responders and non-responders will visit their neurologist in the first cycle of the model (4 weeks) after starting treatment with PR-fampridine to assess response to treatment. It was assumed that no additional administration cost is associated with PR-fampridine, and BSC does not incur drug, administration cost or neurologist visits. Resource use in the base-case analysis was informed by the relationship between medical resource consumption and walking speed, as measured by the T25FW, collected in the Adelphi MS disease-specific programCitation7. Univariate analyses were conducted with the T25FW as the independent variable. Multivariate analyses were also conducted with the following covariates: age, gender, body mass index, months since diagnosis, and relevant comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, arthritis, and osteoporosis. Backward stepwise variable elimination based on individual statistical significance (at 5%) and overall goodness-of-fit measures were applied to optimize the regression model. The final univariate and multivariate equations are available in Supplementary Appendix A. The base-case analysis in the model used the univariate analysis for all resource use items. All direct costs were from the Southern Healthcare Region prices and reimbursements listCitation32 and were inflated to 2018.

Table 6. Direct and indirect cost inputs.

Sensitivity analyses were performed to test the robustness of the model results with respect to the uncertainty around the base-case assumptions and specific parameter estimates. The discount rates of costs and benefits were tested through one-way sensitivity analysis (OWSA) while probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) was used to test the impact of varying multiple input parameters simultaneously (5000 iterations were used). A total of 172 parameters were varied in the PSA, including baseline patient demographics, multiple disease-related parameters, comorbidity factors, healthcare resources and costs, adverse events, utilities and treatment effectiveness parameters. See Supplementary Appendix B for the variation and distributions used for the PSA. Additionally, several scenario analyses tested the impact of varying the perspective, costs, utility scores and time horizon.

Results

In the base-case analysis, use of PR-fampridine led to an incremental QALY gain of 0.12 over BSC (). PR-fampridine was also associated with an incremental cost of 6,982 kr (€685 and $816Citation34]) compared with BSC, resulting in an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for PR-fampridine compared with BSC of 57,109 kr/QALY (€5,607/QALY and $6,675/QALYCitation34). A detailed cost breakdown is presented in .

Table 7. Results: QALYs, LYs, and costs per treatment, over 20 years.

Table 8. Costs per patient per treatment (kr), over 20 years.

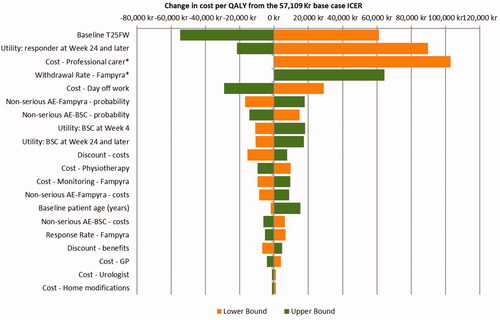

In OWSA, the ICER was most sensitive to the T25FW score at baseline, the utility value assigned to responders at week 24 and carried forward, the cost of professional care, PR-fampridine withdrawal rate and the cost of a day off work ().

Figure 3. Tornado diagram of OWSA.

*Missing bar to the left means PR-fampridine dominates.

Abbreviations. AE, adverse event; BSC, best supportive care; GP, general practitioner; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; PR, prolonged-release; QALY, quality-adjusted life year; T25FW, timed 25-foot walk.

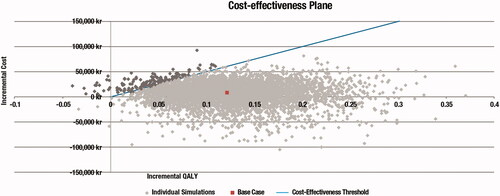

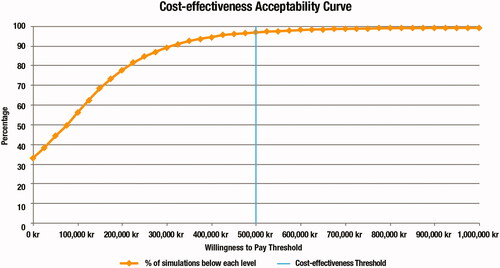

PSA results were similar to the deterministic base-case analysis, with an incremental QALY gain of 0.12 for PR-fampridine compared with BSC, and an ICER of 53,060 kr/QALY (€5,209/QALY and $6,202/QALYCitation34) (). Assuming a threshold of 500,000 kr/QALY (€49,088/QALY and $58,445/QALYCitation34), there was a 96.76% probability of cost-effectiveness at a 56-pack price of 1,402.85 kr ().

The model was run to investigate the impact of different assumptions and data scenarios (). All scenario analyses resulted in ICERs below the threshold with the healthcare payer perspective scenario resulting in the highest ICER (400,936 kr/QALY). PR-fampridine dominated BSC when resource use costs were increased by 25%. A lifetime horizon produced an ICER of 57,109 kr/QALY which is equal to the result in the base case as in the model all patients discontinue treatment before year 20. A 10-year time horizon produced an ICER of 77,605 kr/QALY showing that PR-fampridine remains cost-effective with a shorter time horizon.

Table 9. Cost-effectiveness scenario analysis results for PR-fampridine versus BSC.

Discussion

It has previously been demonstrated in a cross-sectional, patient record-based study in five European countries, that patients with greater walking impairment used significantly more healthcare resources (caregiver support and physician visits) than those with improved mobilityCitation7. However, the cost-effectiveness of treatment for walking impairment in MS has not previously been assessedCitation35. This model compared the cost-effectiveness of PR-fampridine versus BSC alone for the improvement of walking ability from a societal perspective in Sweden. Assuming a willingness-to-pay threshold of 500,000 kr per QALY gained, PR-fampridine had over 96% probability of being cost-effective in Sweden. The ICER was estimated at 57,109 kr/QALY, due to improvements in patients’ quality of life through walking improvement and reduced healthcare resource utilization.

Uncertainty was further extensively explored in scenario analyses, which all showed ICERs falling below the willingness-to-pay threshold. As the model is very sensitive to the utility value assigned to responders at week 24 and carried forward, three scenario analyses were conducted with alternative sets of inputs. As EQ-5D is not a disease-specific instrument, it is likely to lack the sensitivity required to appropriately capture all quality of life changes experienced by MS patients on PR-fampridine. When EQ-5D-3L values from the ENHANCE study were used in the base case, PR-fampridine use was associated with 0.12 incremental QALYs and an ICER of 57,109kr/QALY; when the more sensitive EQ-5D-5L measure from MOBILE study was used, incremental QALYs increased to 0.44 and the ICER decreased to 15,668 kr/QALY. An integrated analysis combined the results from the ENHANCE and MOBILE trialsCitation30. The utility data from the combined trials was used in scenario analyses that also led to a decrease of the ICER to 46,359 kr/QALY. Utility values for BSC and Fampridine responders show a numerical difference at baseline, even if patients were evenly distributed on most of the baseline clinical characteristics in ENHANCECitation28. A scenario analysis was conducted to investigate the impact of such a difference in baseline utility values and resulted in an ICER of 163,202 kr/QALY.

The rate of long-term natural progression of walking impairment taken from the placebo arm of the IMPACT trial was deemed to be relatively conservative compared with other published trialsCitation36–38. Similarly, lack of data demonstrating potential sustained treatment effect following withdrawal from PR-fampridine meant that conservatively, the whole treatment effect was assumed to be lost upon discontinuation of PR-fampridine.

The ability to easily identify treatment responders in clinical practice enables the discontinuation of ineffective treatment in non-responders from as early as 2 weeks after treatment initiationCitation12, reducing an unnecessary burden on both the patient and healthcare system. The model includes 4 weeks of treatment costs in all patients initiating PR-fampridine. In a real-life clinical setting, non-responders may be identified at any time between 2 and 4 weeks, offering the potential for further cost savings on unnecessary PR-fampridine treatment in these individuals that are not captured in the current model.

PR-fampridine is commonly used with DMTs and approximately 40% of patients in the ENHANCE trial were taking concomitant DMTs; most common DMTs were glatiramer acetate, fingolimod, interferon beta-1aCitation18. Therefore, it is important to note that the effect of PR-fampridine seen in the clinical trials and represented in the model is incremental to any effect that DMTs can have on walking impairment. During clinical trials, concomitant DMT medication (except for daclizumab) was allowed, although no change in DMT was allowed for the duration of the trials.

Due to the clinical indication of PR-fampridine between EDSS 4 and 7, baseline patients on ENHANCE trial were older (mean age approximately 49 years) and had a longer time since diagnosis (approximately 14 years) compared to other trials for DMTs in MS. The OWSA and PSA tested the impact of variation in patients’ baseline characteristics and the results were generally insensitive to variations in those parameters.

Limitations

There were some data limitations when developing this model. Data collected in extension studiesCitation22 were available for up to 5 years following the end of the original Phase III trialsCitation15,Citation16, requiring extrapolation of T25FW data to model the long-term treatment effect.

Treatment response is defined in the model per the MSWS-12 whilst disease progression is defined according to T25FW, due to the lack of long-term data on this variable and data showing how MSWS-12 is related to resource use.

Resource use data were sourced from a study that was conducted in the five major European marketsCitation7, so these values were not specific to the Swedish market, although the associated costing analysis was. According to a large MS burden of illness study conducted in Sweden and 15 other European countries, the direct healthcare costs, informal care costs, and production losses were similar in Sweden compared to other European countries. This publication provides evidence that using data from other European countries might have some degree of applicability to the Swedish settingCitation9.

The PSA did not account for the possible pairwise correlations between relevant inputs, and may therefore overestimate the variability of the probabilistic results displayed in the cost-effectiveness plane. Further research is required to address the current lack of evidence on possible correlations between inputs to provide more robust analyses.

Conclusions

PR-fampridine in combination with BSC improves walking ability compared with BSC alone as a treatment for patients with MS and EDSS 4-7. The addition of PR-fampridine to BSC resulted in an ICER of 57,109 kr/QALY (€5,607/QALY and $6,675/QALYCitation34), which is below an assumed willingness-to-pay threshold of 500,000 kr per QALY gained (€49,088/QALY and $58,445/QALYCitation34). PR-fampridine, therefore, represents a cost-effective treatment for MS-related walking impairment in Sweden, due to improvements in patients’ quality of life through walking improvement and reduced healthcare resource utilization.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was sponsored by Biogen (Baar, Switzerland). Writing and editorial support for the preparation of this manuscript were provided by OPEN Health; funding was provided by Biogen.

Declaration of financial/other interests

AC, EM and GM. are employees of and hold stock/stock options in Biogen.

DT and LT were employees of Biogen at the time the study was conducted and the manuscript drafted.

LJ received travel support and/or lecture honoraria from Biogen, Novartis, Teva, Sanofi Genzyme, Roche, Alexion and Merck; served on scientific advisory boards for Almirall, Teva, Biogen, Novartis, Sanofi Genzyme, Alexion, and Merck; serves on the editorial board of the Acta Neurologica Scandinavica and received unconditional research grants from Biogen, Novartis, and Teva.

RS and AN received research funding from Biogen for the research to which this manuscript pertains.

A reviewer on this manuscript has disclosed that they are speaker for most of the multiple sclerosis disease modifying companies, including Biogen. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in the conception and design of this manuscript, in addition to revising it critically for intellectual content. All authors reviewed and provided feedback on the manuscript. The authors had full editorial control, provided their final approval of the version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Writing assistance was provided by OPEN Health, who drafted the manuscript based on input from authors.

Previous presentations

None.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (111.5 KB)Acknowledgements

This manuscript is dedicated to the memory of Thibaut Dort, Economic Modeling Lead, Global Value & Access at Biogen. Thibaut was instrumental in developing this model but sadly passed away in April 2019 before this manuscript was completed.

Notes

i Marketed by Biogen Inc. outside of United States of America (USA) and by Acorda Therapeutics, Inc. in the USA.

References

- Hartung H-P. Impact of mobility impairment in multiple sclerosis 1-healthcare professionals perspectives. Euro Neurol Rev. 2011;6(2):110.

- Hemmett L, Holmes J, Barnes M, et al. What drives quality of life in multiple sclerosis? QJM. 2004;97(10):671–676.

- Rajagopalan K, Jones E, Pike J, et al., editors. Emergence of walking and mobility problems among patients with multiple sclerosis and its impact on quality of life: a cross-sectional assessment in 5 EU countries. Paper presented at the 26th Congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ECTRIMS); 2010 October 13–16; Gothenburg, Sweden.

- Cohen JA, Krishnan AV, Goodman AD, et al. The clinical meaning of walking speed as measured by the timed 25-foot walk in patients with multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(11):1386–1393.

- Kohn CG, Baker WL, Sidovar MF, et al. Walking speed and health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Patient. 2014;7(1):55–61.

- Larocca NG. Impact of walking impairment in multiple sclerosis: perspectives of patients and care partners. Patient. 2011;4(3):189–201.

- Pike J, Jones E, Rajagopalan K, et al. Social and economic burden of walking and mobility problems in multiple sclerosis. BMC Neurol. 2012;12(1):94.

- Carroll CA, Fairman KA, Lage MJ. Updated cost-of-care estimates for commercially insured patients with multiple sclerosis: retrospective observational analysis of medical and pharmacy claims data. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):286.

- Kobelt G, Thompson A, Berg J, et al. New insights into the burden and costs of multiple sclerosis in Europe. Mult Scler. 2017;23(8):1123–1136.

- Reese JP, John A, Wienemann G, et al. Economic burden in a German cohort of patients with multiple sclerosis. Eur Neurol. 2011;66(6):311–321.

- Trisolini M, Honeycutt A, Wiener J, et al. Global economic impact of multiple sclerosis. London (UK): Multiple Sclerosis International Federation; 2010.

- Biogen. Fampyra – summary of product characteristics [Internet]. European Medicines Agency; 2018 [cited 2020 Jul 22]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/fampyra-epar-product-information_en.pdf

- Cameron MH, Wagner JM. Gait abnormalities in multiple sclerosis: pathogenesis, evaluation, and advances in treatment. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2011;11(5):507–515.

- Motl RW. Benefits, safety, and prescription of exercise in persons with multiple sclerosis. Expert Rev Neurother. 2014;14(12):1429–1436.

- Goodman AD, Brown TR, Edwards KR, et al. A phase 3 trial of extended release oral dalfampridine in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2010;68(4):494–502.

- Goodman AD, Brown TR, Krupp LB, et al. Sustained-release oral fampridine in multiple sclerosis: a randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373(9665):732–738.

- Hupperts R, Lycke J, Short C, et al. Prolonged-release fampridine and walking and balance in MS: randomised controlled MOBILE trial. Mult Scler. 2016;22(2):212–221.

- Hobart J, Ziemssen T, Feys P, et al. Assessment of clinically meaningful improvements in self-reported walking ability in participants with multiple sclerosis: results from the randomized, double-blind, phase III ENHANCE trial of prolonged-release fampridine. CNS Drugs. 2019;33(1):61–79.

- Hernandez L, O’Donnell M, Postma M. Modeling approaches in cost-effectiveness analysis of disease-modifying therapies for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: an updated systematic review and recommendations for future economic evaluations. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36(10):1223–1252.

- Tandvårds-Läkemedelförmånsverket - TLV. Fampyra is included in the high-cost protection [Internet]. Stockholm (Sweden): Tandvårds-läkemedelsförmånsverket; 2018 [cited 2020 Apr 9]. Available from: https://www.tlv.se/beslut/beslut-lakemedel/generell-subvention/arkiv/2018-10-31-fampyra-ingar-i-hogkostnadsskyddet.html

- Tandvårds-Läkemedelförmånsverket - TLV. General guidelines for economic evaluations from the Pharmaceutical Benefits Board (LFNAR 2003:2) [Internet]. Stockholm (Sweden): Tandvårds-läkemedelsförmånsverket; 2003 [cited 2019 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.tlv.se/download/18.2e53241415e842ce95514e9/1510316396792/Guidelines-for-economic-evaluations-LFNAR-2003-2.pdf

- Goodman AD, Bethoux F, Brown TR, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of dalfampridine for walking impairment in patients with multiple sclerosis: results of open-label extensions of two Phase 3 clinical trials. Mult Scler. 2015;21(10):1322–1331.

- Schapiro RB, Brown F, Wiliamson T, et al. Open-label extension patient retention rates with dalfampridine extended release tablets in multiple sclerosis. Paper presented at ECTRIMS 28th Congress (European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis); 2012 October 10–13; Lyon, France.

- Kingwell E, van der Kop M, Zhao Y, et al. Relative mortality and survival in multiple sclerosis: findings from British Columbia, Canada. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83(1):61–66.

- Statistics Sweden (SCB). Popular statistics [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2018 November 04] Available from: http://www.scb.se/en/

- Mehta L, McNeill M, Hobart J, et al. Identifying an important change estimate for the Multiple Sclerosis Walking Scale-12 (MSWS-12v1) for interpreting clinical trial results. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2015;1:2055217315596993.

- Krishnan AGA, Potts J, Cohen J. Health-related quality of life is reduced in multiple sclerosis patients whose walking speed declines over time. Paper presented at 64th AAN Annual Meeting (American Academy of Neurology); 2012 April 21–28; New Orleans, LA

- Hobart J, Hupperts R, Linnebank M, et al. Health-related quality of life improved in people with multiple sclerosis who had clinically meaningful changes in walking ability with PR-Fampridine: post hoc analysis of ENHANCE. Poster presented at the World Congress of Neurology; 2017 September 16–21; Kyoto, Japan.

- Liu YMM, Lee A, Zhong J, et al. Quality of life among patients with multiple sclerosis treated with prolonged-release fampridine 10 mg tablets twice daily for walking impairment: post hoc analysis of the mobile study. Poster presented at the 17th Annual European Congress; 2014 November 8–12; Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

- Hupperts R, Hobart J, Gasperini C, et al. Efficacy of prolonged-release fampridine vs placebo on walking ability, dynamic and static balance and quality-of-life: an integrated analysis of MOBILE and ENHANCE. Mult Scler. 2018;24(S2):315.

- van Hout B, Janssen MF, Feng YS, et al. Interim scoring for the EQ-5D-5L: mapping the EQ-5D-5L to EQ-5D-3L value sets. Value Health. 2012;15(5):708–715.

- Regionvårdsnämnden S. Regionala priser och ersättningar för Södra sjukvårdsregionen 2018 [Internet]. Lund (Sweden): Södra regionvårdsnämndens kansli; 2017 [cited 2018 April 10]. Available from: http://sodrasjukvardsregionen.se/avtal-priser/regionala-priser-och-ersattningar/

- Berg J, Lindgren P, Fredrikson S, et al. Costs and quality of life of multiple sclerosis in Sweden. Eur J Health Econ. 2006;7(S02):75–85.

- XE. Xe currency converter [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 April 8]. Available from: https://www.xe.com/currencyconverter/

- Guo S, Pelligra C, Saint-Laurent Thibault C, et al. Cost-effectiveness analyses in multiple sclerosis: a review of modelling approaches. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014;32(6):559–572.

- Fox RJ, Miller DH, Phillips JT, et al. Placebo-controlled phase 3 study of oral BG-12 or glatiramer in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(12):1087–1097.

- Gold R, Kappos L, Arnold DL, et al. Placebo-controlled phase 3 study of oral BG-12 for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(12):1098–1107.

- Steiner D, Arnold AD, Freeman MS, et al. Natalizumab versus placebo in patients with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (SPMS): results from ASCEND, a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized phase 3 clinical trial. 2016. Vancouver (Canada): AAN.