Abstract

Aims

Single-tablet regimens (STRs) can improve antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence; however, the relationship between long-term adherence and patient healthcare resource utilization (HRU) is unclear. The objective of this study was to assess long-term ART adherence among people living with HIV (PLHIV) using STRs and multi-tablet regimens (MTRs) and compare HRU over time by adherence.

Materials and methods

This retrospective study analyzed medical and pharmacy claims (Optum Clinformatics Data Mart Database). Included PLHIV were aged ≥18 years, had ≥1 medical claim with an HIV diagnosis, and had pharmacy claims for a complete STR or MTR. Adherence was analyzed as the proportion of days covered (PDC), stratified as ≥95%, very high; 90–95%, high; 80–90%, moderate; <80%, low. Cumulative all-cause and HIV-related HRU were calculated across 4 years. Among PLHIV with ≥4-year follow-up, HRU was assessed by adherence.

Results

Among 15,153 PLHIV included, 63% achieved PDC ≥90% during Year 1. Among the subgroup of PLHIV with ≥4-year follow-up (N = 3,818), the proportion maintaining PDC ≥90% fell from 67% in Year 1 to 54% by Year 4. The difference from Years 1 to 4 in the proportion of PLHIV with PDC ≥90% was 13% and 17% in the STR and MTR groups, respectively. Cumulative HRU across the 4-year follow-up was higher in PLHIV with low vs high adherence (27% with low adherence had ≥1 emergency room visit vs 17% for very high, p < .0001; 15% with low adherence had ≥1 inpatient stay vs 7% for very high, p < .0001).

Conclusions

ART adherence showed room for improvement, particularly over the long term. PLHIV receiving STRs exhibited higher adherence vs those receiving MTRs; this difference increased over time. The proportion of PLHIV with higher HRU was significantly higher among those with lower adherence and became greater over time. Interventions and alternative therapies to improve adherence among PLHIV should be explored.

Introduction

Since its emergence in the 1980s, the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic in the United States (US) has changed dramatically. It is estimated that around 1.2 million people are currently living with HIV in the US [Citation1]; however, advances in antiretroviral treatment (ART) have shifted it from a fatal diagnosis to a chronic, manageable disease requiring lifelong therapy. Typical ART consists of a combination of antiretroviral (ARV) agents which target multiple pathways in the HIV replication cycle. The Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) guidelines recommend an ART regimen with at least two fully active agents from mechanistically distinct classes to help achieve and sustain virologic suppression [Citation2].

Maintaining high adherence to daily ART medications is essential in HIV therapy to keep the virus undetectable and prevent the development of resistance or transmission to others [Citation2,Citation3]; adherence to ART of 95% or greater is generally required for optimal viral suppression [Citation4]. As such, adherence remains a key concern for people living with HIV (PLHIV) and clinicians, especially with daily oral dosing regimens and intolerabilities associated with long-term ART [Citation5,Citation6]. Many factors have been identified as contributors to suboptimal ART adherence, with some of the most common patient-reported reasons being simply forgetting to take the medication, traveling, being too busy, changing the daily routine, and falling asleep earlier or sleeping later than usual [Citation6–9].

More recently, ART has evolved from multi-tablet regimens (MTRs, consisting of two or more pills) to single-tablet regimens (STRs). Several studies have found PLHIV receiving STRs show superior medication adherence, treatment retention, and viral suppression than those receiving MTRs [Citation10–13]. An association between higher adherence rates and reduced healthcare resource utilization (HRU) has been demonstrated in PLHIV. Greater adherence to ART is associated with significantly lower annual medical costs and a lower rate of hospitalization [Citation14].

Although adherence to ART and associated HRU are central issues in modern HIV treatment, current literature on long-term adherence to ART (longer than 1 year) and the impact on HRU in the commercially insured US population is limited. To address this gap, we conducted a study to evaluate yearly and longer-term ART adherence among PLHIV treated with STRs and MTRs. Additionally, we described HRU over time by adherence level, to better understand adherence and HRU outcomes among commercially insured PLHIV.

Methods

Data source and study design

This retrospective longitudinal cohort study utilized commercial claims data from Optum’s de-identified Clinformatics Data Mart Database [Citation15] covering 14 million annual lives of members in all 50 US states and includes demographic information, filled prescription data, and inpatient (IP) and outpatient (OP) medical encounters.

The index date was defined as the date of the earliest identified pharmacy claim during the study period (January 1, 2011 to December 31, 2017) for a complete ART regimen with a duration of ≥60 continuous days. For MTRs, the index was the date by which all agents were available simultaneously, and where a complete ART regimen was composed of at least three agents, including a core and a backbone agent, across at least two classes [Citation2]. For STRs, a complete ART regimen was defined as a filled prescription for Symtuza, Genvoya, Stribild, Delstrigo, Symfi, Biktarvy, Odefsey, Triumeq, Complera, Atripla, or Juluca. Baseline characteristics were measured in the 3 months pre-index period, and PLHIV were followed for at least 12 months post-index, until the end of eligibility or death. As the study used only de-identified patient data, it was exempt from Institutional Review Board review/approval.

Patient selection

Adult PLHIV (≥18 years of age at the date of the index) with pharmacy claims for a complete multi-class ART regimen lasting at least 60 days, at least one medical claim with a diagnosis of HIV in the study period (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM]: V08, 042xx; ICD-Tenth Revision [Citation10]-CM: Z21, B20), and continuous eligibility for at least 3 months before (baseline period) and 12 months after the index date (observation period) were included in the study. PLHIV were excluded from the analysis if they had a diagnosis of HIV-2 (ICD-9-CM: 079.53; ICD-10-CM: B97.35) at any point in the study period.

Study measures

Patient demographics were assessed during the baseline period, and these included age at index, gender, geographic location, and treatment history (naïve or experienced). PLHIV without any ART before the index date were considered treatment naïve, while those who did have ART were considered treatment-experienced. Adherence to a complete STR or MTR was measured as the proportion of days covered (PDC), defined as the number of non-overlapping days in the period that was covered by any complete regimen of the index type (either STR or MTR), divided by the number of days in a fixed period of 1 year. PLHIV who switched from an MTR to an STR (or vice versa) for ≥60 days were censored and excluded from the subsequent years’ PDC calculations. PLHIV switching from MTR to STR for fewer than 60 days was included but these days did not count towards their PDC. PDC was examined in the first year of the observation period overall, and years following the index among PLHIV with at least 4 years of continuous data. PDC among PLHIV was categorized as low (PDC <80%), moderate (80% to 90%), high (90% to 95%), or very high (PDC ≥95%) adherence.

All-cause and HIV-related HRU, including IP stays, OP, and emergency room (ER) visits, were assessed in the baseline period and the entire observation period. The rate of HRU events was calculated on a per-person-per-month (PPPM) basis in the baseline period and a per-person-per-year (PPPY) basis in the observation period. HIV-related encounters were determined by identifying claims with an associated HIV diagnosis in any position. IP stays included claims for acute care and skilled nursing facilities, and length of IP stay was calculated on a per-stay basis across all stays. OP visits included ER visits, laboratory tests, and visits related to routine medical care. Routine medical care included diagnostic testing, immunization and injections, consultation, mental health, and preventative medicine.

Statistical analyses

The study size was dependent on the number of patients meeting eligibility criteria within the selected database so there was no pre-specified sample size. Unadjusted statistical tests and multivariate-adjusted analyses were used for the comparisons conducted in this study. Patients with missing data were not included. If patients were lost to follow-up 12 months after the index date, they were censored. If they were lost to follow-up within 12 months following the index, they were excluded from the study sample.

Descriptive statistics were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and frequencies and proportions for categorical variables. PDC was assessed yearly, calculated by regimen type (STR vs MTR), and described using mean ± SD. The frequency and proportion of PLHIV with PDC ≥90% were tabulated for each yearly assessment. Multivariate analyses were conducted using logistic, negative binomial, or linear regressions for binary, count or continuous measures of PDC, respectively, accounting for baseline characteristics that were statistically significantly different (p < .05) between patients receiving STR vs. MTR.

The frequency and proportion of PLHIV with ≥1 OP visit, IP stay, or ER visit, along with the average number of OP visits PPPY and the average length of IP stays were calculated for the overall sample and stratified by ART regimen (STR or MTR) and categories of adherence. HRU and PDC were assessed cumulatively among PLHIV who had at least 4 years of follow-up. PDC was compared between STR vs MTR regimen types. HRU was compared between the lowest PDC adherence category (<80%) vs the highest PDC adherence category (≥95%). Wilcoxon rank-sum test and Chi-square (or Fisher’s exact, as appropriate) tests were used to compare continuous and categorical variables, respectively. All analyses were carried out using SAS Enterprise Guide version 7.1 (Cary, NC, USA). Comparisons with a p-value < .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Study population

A total of 38,247 PLHIV had pharmacy claims for a complete ARV regimen with a duration of at least 60 continuous days, among which, 38,246 PLHIV had one or more medical claims with an HIV diagnosis at any time between 2011 and 2017. The criteria of continuous eligibility of at least 3 months before and at least 12 months after the first claim for a complete ARV regimen was met by 15,831 PLHIV. Of these, 15,740 PLHIV were at least 18 years of age on the index date (date of their first claim of complete ARV regimen) and 15,153 PLHIV were without a medical claim with a diagnosis of HIV-2 at any time. Consequently, 15,153 PLHIV met the study inclusion criteria; 8,715 (58%) were receiving STRs and 6,438 (42%) were receiving MTRs at the index date. None of the patients included in the study had missing variables.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics are shown in . The mean age was 43.9 years overall and was higher in the MTR group than in the STR group (46.2 and 42.2 years, respectively). Most PLHIV were male (88%) and from the South (53%). Around 40% of PLHIV overall had an index date in 2011; 34% in the STR vs 50% in the MTR group. The mean duration of follow-up in the overall sample was 3.0 years, and approximately one-quarter of PLHIV had four or more years of follow-up in the study period. Patients in the MTR group had longer years of follow-up on average (3.2) than the MTR group (2.9) and had more patients (29%) followed for four or more years than the STR group (23%). Most PLHIV were treatment-experienced (82%); however, there was a higher proportion who were treatment-naïve in the STR than the MTR group (24% vs 11%).

Table 1. Baseline patient demographic characteristics, overall and stratified by STR vs MTR.a.

In the overall sample, most PLHIV had at least one all-cause (85%) or HIV-related (76%) OP visit during the 3-month baseline period. Only 3.8% of PLHIV had at least one all-cause IP stay and 8.5% of PLHIV had at least one all-cause ER visit. The distribution of HRU during the baseline period was similar between the STR and MTR groups (data not shown).

Adherence

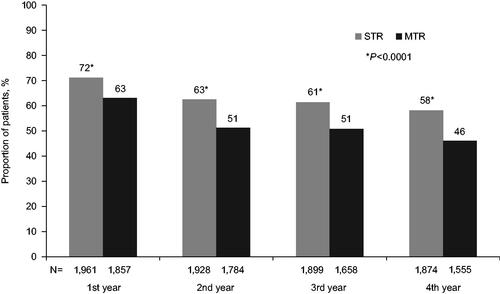

During the first year of follow-up, 63% of PLHIV in the overall cohort had PDC ≥90%. Adherence was generally lower in the MTR group compared with the STR group, with a smaller proportion of PLHIV in the MTR group achieving PDC ≥90% compared with the STR group in the first year (58% vs 67%; ). When analyzed over time, the proportion of patients with PDC ≥90% showed a decreasing trend with each additional year of follow-up. In the subgroup of PLHIV with at least 4 years of follow-up, PDC ≥90% fell from 67% in Year 1 to 53% by Year 4.

Table 2. Adherence during the first year of follow-up and across 4-years of follow-up.

The trend of decreasing adherence over time was observed in both the MTR and STR groups; however, there was a greater decrease in the proportion of PLHIV with PDC ≥90% in the MTR group (). The difference in the proportion of PLHIV with PDC ≥90% from Year 1 to Year 4 was 13% in the STR group compared with 17% in the MTR group. Additionally, the proportion of PLHIV with PDC ≥90% was consistently higher in those receiving STR throughout the study period.

Figure 1. Proportion of PLHIV with ≥90% adherence over time with ≥4 years of follow-up, stratified by STR vs MTR. Wilcoxon rank-sum tests and Chi-square tests were used for comparison of continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Comparisons between STR and MTR by year that were significant at the p < .001 level are marked with an asterisk (*). HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; MTR: multi-tablet regimen; PLHIV: people living with HIV; STR: single-tablet regimen.

Health resource utilization

All-cause and HIV-related HRU for the overall population and the STR and MTR groups are shown in . In summary, almost all PLHIV had ≥1 OP visit over the study period (99.9%), 38% had ≥1 ER visit, and 14% ≥1 IP stay (all-cause HRU). The mean number of OP visits in the overall population was 11.95 and the mean number of IP stays was 0.09. There were higher incidences of ER visits and IP stays and longer mean IP stays in the MTR group compared with the STR group. Similar patterns were observed for all-cause and HIV-related HRU.

Table 3. All-cause and HIV-related HRU in the overall sample during the observation period and stratified by ART regimen.

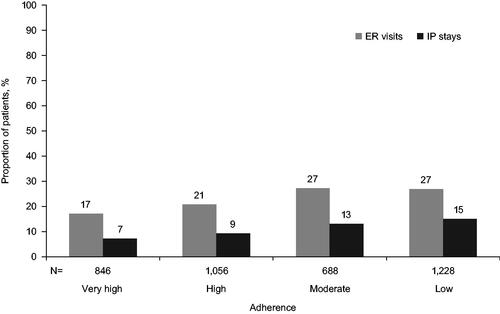

In addition, all-cause and HIV-related HRU in the overall population was assessed by year of follow-up and stratified by adherence category. Over the 4-year follow-up period, the cumulative number of HIV-related ER visits increased over time from 9.3% in Year 1 to 23% by Year 4, and IP stays also increased from 4.2% in Year 1 to 11.4% by Year 4, with similar trends for all-cause ER visits and IP stays. A significantly higher proportion of PLHIV with ≥1 HIV-related IP stay or ≥1 ER visit was observed among those with low adherence compared with those with very high adherence (p < .0001) (). This difference was present from Year 1 and grew larger over time. Across 4 years of follow-up, 27% of PLHIV in the moderate or low adherence categories had ≥1 HIV-related ER visit compared with 17% in the very high adherence group, and about twice as many IP stays (13–15%) compared with the very high adherence group (7%) (). The same trend was seen for all-cause ER visits and IP stays (data not shown). Further, PLHIV in the low adherence category were also more likely to have ≥2 HIV-related ER visits and IP stays compared with those in the very high adherence category (ER: 10.2% vs 4.6%, IP: 5.0% vs 1.5%; p < .0001).

Figure 2. The proportion of PLHIV with ≥1 HIV-related ER or IP stays with ≥4-years of follow-up, by adherence category. Adherence among PLHIV was categorized as low for PDC <80%, moderate for 80–90%, high for 90–95%, or very high for PDC ≥95%. The difference between the low and very high adherence at the 4-year follow-up was: IP stay, 15.1% vs 7.2%, p < .0001 and ER visit, 26.9% vs 17.1%, p < .0001. ER: emergency room; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; IP: inpatient; PDC: proportion of days covered; PLHIV: people living with HIV.

Discussion

This study has demonstrated that among commercially insured PLHIV during the first year of follow-up, most (63%) had high adherence (PDC ≥90%). When stratified by ART regimen type, results showed that PLHIV treated with STRs had significantly higher adherence in the first year and over time compared with the MTR group. This finding is consistent with previous studies of ART adherence, which have reported higher adherence to ART regimens of a single pill vs multiple pills per day among US Veterans, Medicaid enrollees, and commercially insured populations [Citation14,Citation16,Citation17].

To build upon previous work assessing adherence to ARTs based on STRs and MTRs, our study has examined adherence every year. Among PLHIV with at least 4 years of follow-up, adherence showed a decreasing trend with each year. At each year of follow-up, the STR group had higher adherence than the MTR group, and the difference between these groups grew year over year. The decreases in adherence for both groups indicate PLHIV may have difficulty maintaining optimal adherence over the long term, which can be due to multiple factors as discussed previously. For some PLHIV, daily pill regimens are an unremitting reminder of their disease, affecting their emotional well-being and contributing to the burden of the disease [Citation18–20]. Many PLHIV also reports a fear of unwanted disclosure of their HIV and anxiety with taking daily ART in inconvenient situations or public settings, which results in some PLHIV skipping or delaying doses to avoid this involuntary disclosure and subsequent stigma [Citation21]. Switching to a regimen with less frequent dosing may be beneficial to PLHIV who experience challenges with maintaining adherence to a more complicated daily oral ART regimen.

Due to advances in treatment, HIV has developed into a chronically managed disease with PLHIV living much longer while accessing HIV treatment and as such, associated HRU and its costs are critical issues in the HIV treatment landscape. In this study, significantly lower proportions of PLHIV with very high adherence (≥95%) had all-cause or HIV-related ER visits and IP stays than those with low adherence (<80%), and this difference grew larger over time which corresponded to the decreasing adherence trends over time. This association of higher rates of HRU in PLHIV with low adherence was the following results observed in other studies [Citation22]. These findings indicate that improving adherence could help to reduce HRU and associated costs among PLHIV. We recommend additional research in this area evaluating the longitudinal outcomes seen in this study in other populations and data sources.

Data on the rates of HRU in the study population have indicated that PLHIV receiving STRs had lower rates of all-cause and HIV-related IP stays, and shorter lengths of stay than those receiving MTRs. This is in line with previous studies that have identified a lower risk of hospitalization with PLHIV treated with STRs in commercially insured and Medicaid populations [Citation16,Citation17,Citation23]. OP and ER visits were also lower for the STR group. Healthcare costs are a key issue in the new era of HIV treatment, and these results highlight the importance of an ART regimen on HRU occurrence and related costs. Current HIV treatment guidelines recommend STRs if desired; however, they also include MTRs as recommended regimens [Citation2]. In light of these results indicate a higher adherence and lower HRU burden among PLHIV on STRs, these should be prioritized in guidelines when possible.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. Firstly, identifying drug-specific ART combination regimens in administrative claims data is complex, as different drugs in the regimen may not be filled at the same time, and may have different days of supply. To ensure all PLHIV included in the study sample were receiving complete ART regimens, the study required at least 60 continuous days to be covered by all regimen components. This strict method of inclusion may have resulted in the exclusion of PLHIV who were practically on a complete ART regimen, with only short gaps between fills. Secondly, the use of pharmacy claims data does not provide information on whether the medications were taken as prescribed, if at all, and the assigning of PLHIV into adherence levels may not accurately reflect the ARTs taken or the association with subsequent HRU outcomes. Additionally, Optum’s de-identified Clinformatics Data Mart Database does not provide information on drugs dispensed during IP stays. Furthermore, this database provides no information on patient characteristics such as socioeconomic factors (e.g. race/ethnicity, education, housing status). There could also be a form of channeling bias of prescribing an STR vs MTR which we could not account for using an administrative claims database. Classifying HIV-related claims by the presence of an HIV diagnosis code could underestimate the number of HIV-related healthcare utilization. Finally, the use of this database as the data source may not be generalizable to the entire PLHIV population and the requirement of continuous insurance coverage throughout the study period would have missed PLHIV who may have died due to their disease or other causes.

Conclusions

In this study, adherence to ART regimens showed room for improvement in the first year of observation, and those receiving STRs have higher adherence compared with those receiving MTRs. Over the study period, adherence showed a decreasing trend year over year, with less than half of PLHIV achieving very high levels of ART adherence after only 1 year, which fell to less than a quarter by Year 4. The proportion of PLHIV with ER visits and IP stays was significantly higher in PLHIV with low adherence in Year 1, with the difference becoming more pronounced by Year 4 of follow-up. Maintaining high adherence is a critically important aspect of therapy for PLHIV, and these findings suggest that interventions or alternative therapy options to promote long-term adherence should be explored. Future research should investigate the association of long-term adherence and HRU within Medicaid and Medicare populations, as these payer types are highly important in the treatment of PLHIV.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by ViiV Healthcare.

Declaration of financial/other interests

JP, AO, and CG are employees of ViiV Healthcare and own stock/stock options in GlaxoSmithKline/ViiV Healthcare. RHB, MD, CK, EF, SP, and MSD are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that provided paid consulting services to ViiV Healthcare. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

JP contributed to the conception and study design, acquisition of data, and interpretation of results. RHB contributed to the study design, acquisition of data, data analysis, and interpretation of results. MD contributed to the study design, acquisition of data, data analysis, and interpretation of results. AO contributed to the conception and study design and interpretation of results. CK contributed to the study design, acquisition of data, data analysis, and interpretation of results. EF contributed to the study design, acquisition of data, data analysis, and interpretation of results. SP contributed to the study design, acquisition of data, data analysis, and interpretation of results. MSD contributed to the study design, acquisition of data, data analysis, and interpretation of results. CG contributed to the conception and study design and interpretation of results. All authors critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Previous presentations

Study results have been previously presented at IDWeek 2019; October 2–6, 2019; Washington, DC, and AMCP Nexus 2019; October 29-November 1, 2019; National Harbor, MD.

Data sharing statement

Anonymized individual participant data and study documents can be requested for further research from www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com.

Acknowledgements

Editorial support was provided by Hannah Cahill, Ph.D., and Laura Whiteley, Ph.D., at Fishawack Indicia LTD, UK, and was funded by ViiV Healthcare.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States, 2010–2016. Atlanta (GA): US Department of Health and Human Services; 2019. (HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report; volume 24, no. 1).

- Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents. Rockville (MD): US Department of Health and Human Services; 2019. [cited 2021 June 6]. Available from: https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/sites/default/files/guidelines/documents/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf. Accessed

- Li JZ, Gallien S, Ribaudo H, et al. Incomplete adherence to antiretroviral therapy is associated with higher levels of residual HIV-1 viremia. AIDS. 2014;28(2):181–186.

- Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(1):21–30.

- Holtzman CW, Brady KA, Yehia BR. Retention in care and medication adherence: current challenges to antiretroviral therapy success. Drugs. 2015;75(5):445–454.

- Genberg BL, Lee Y, Rogers WH, et al. Four types of barriers to adherence of antiretroviral therapy are associated with decreased adherence over time. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(1):85–92.

- Al-Dakkak I, Patel S, McCann E, et al. The impact of specific HIV treatment-related adverse events on adherence to antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Care. 2013;25(4):400–414.

- Lucas GM. Substance abuse, adherence with antiretroviral therapy, and clinical outcomes among HIV-infected individuals. Life Sci. 2011;88(21-22):948–952.

- Gonzalez JS, Batchelder AW, Psaros C, et al. Depression and HIV/AIDS treatment nonadherence: a review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;58(2):181–187.

- Clay PG, Nag S, Graham CM, et al. Meta-analysis of studies comparing single and multi-tablet fixed dose combination HIV treatment regimens. Medicine. 2015;94(42):e1677.

- Hanna DB, Hessol NA, Golub ET, et al. Increase in single-tablet regimen use and associated improvements in adherence-related outcomes in HIV-infected women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65(5):587–596.

- Hemmige V, Flash CA, Carter J, et al. Single tablet HIV regimens facilitate virologic suppression and retention in care among treatment naïve patients. AIDS Care. 2018;30(8):1017–1024.

- Nachega JB, Mugavero MJ, Zeier M, et al. Treatment simplification in HIV-infected adults as a strategy to prevent toxicity, improve adherence, quality of life and decrease healthcare costs. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2011;5:357–367.

- Kangethe A, Polson M, Lord TC, et al. Real-world health plan data analysis: key trends in medication adherence and overall costs in patients with HIV. JMCP. 2019;25(1):88–93.

- OptumInsight. Optum clinformatics data mart. Eden Prairie (MN). 2014. Available from: https://www.optum.com/content/dam/optum/resources/productSheets/Clinformatics-Data-Mart.pdf

- Sutton SS, Hardin JW, Bramley TJ, et al. Single- versus multiple-tablet HIV regimens: adherence and hospitalization risks. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22(4):242–248.

- Sax PE, Meyers JL, Mugavero M, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral treatment and correlation with risk of hospitalization among commercially insured HIV patients in the United States. PLOS One. 2012;7(2):e31591.

- Grierson J, Pitts M, Koelmeyer R. HIV futures seven: the health and wellbeing of HIV positive people in Australia. Melbourne (Australia): LaTrobe University, Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society; 2013. (Monograph series number 88).

- Kerrigan D, Mantsios A, Gorgolas M, et al. Experiences with long acting injectable ART: a qualitative study among PLHIV participating in a phase II study of cabotegravir + rilpivirine (LATTE-2) in the United States and Spain. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0190487.

- Relf MV, Williams M, Barroso J. Voices of women facing HIV-related stigma in the Deep South. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2015;53(12):38–47.

- Katz IT, Ryu AE, Onuegbu AG, et al. Impact of HIV-related stigma on treatment adherence: systematic review and meta-synthesis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16(3 Suppl 2):18640.

- Zhang S, Rust G, Cardarelli K, et al. Adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy impact on clinical and economic outcomes for medicaid enrollees with human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C coinfection. AIDS Care. 2015;27(7):829–835.

- Cohen CJ, Meyers JL, Davis KL. Association between daily antiretroviral pill burden and treatment adherence, hospitalisation risk, and other healthcare utilisation and costs in a US medicaid population with HIV. BMJ Open. 2013;3(8):e003028.