Abstract

Aims

To compare health care resource utilization (HCRU), short-term disability days, and costs between states of persistence on antidepressant lines of therapy after evidence of treatment-resistant depression (TRD).

Methods

Patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) were identified in the IBM MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Supplemental Databases (01/01/2013–03/04/2019), Multi-State Medicaid Database (01/01/2013–12/31/2018), and Health Productivity Management Database (01/01/2015–12/31/2018). The index date was the date of the first evidence of TRD during the first observed major depressive episode. The follow-up period was divided into 45-day increments and categorized into persistence states: (1) evaluation (first 45 days after evidence of TRD); (2) persistence on the early line after evidence of TRD; (3) persistence on a late line; and (4) non-persistence. HCRU, short-term disability days, and costs were compared between persistence states using multivariate generalized estimating equations.

Results

Among 10,053 patients with TRD, the evaluation state was associated with higher likelihood of all-cause inpatient admissions (odds ratio [OR; 95% confidence interval (CI)] = 1.79 [1.49, 2.14]), emergency department visits (OR [95% CI] = 1.23 [1.12, 1.34]), and outpatient visits (OR [95% CI] = 3.83 [3.51, 4.18]; all p < .001) versus persistence on the early-line therapy. This resulted in $374 higher mean PPPM all-cause health care costs (95% CI = 265, 470; p < .001) during evaluation versus persistence on the early line therapy. The evaluation state was associated with 89% more short-term disability days (OR [95% CI] = 1.89 [1.49, 2.57] and $212 higher mean PPPM short-term disability costs (95% CI = 64, 259) relative to persistence on the early line (both p < .001). Moreover, during persistence on a later line, mean PPPM all-cause health care costs were $141 higher (95% CI = 13, 242; p = .028) relative to the early line.

Limitations

Medication may have been dispensed but not actually taken.

Conclusions

Higher costs during the first 45 days after evidence of the presence of TRD and during persistence on a late line relative to persistence on the early-line therapy suggest there are benefits to using more effective treatments earlier.

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a disabling psychiatric condition with an estimated annual prevalence of 7.8% in the United States (US)Citation1. Approximately one in three patients who receive pharmacologic therapy for MDD do not respond to at least 2 courses of antidepressant medications of adequate dose and duration; such patients are commonly defined as having treatment-resistant depression (TRD) in the literatureCitation2–4 and by the US Food and Drug AdministrationCitation5. Treatment failure may be due to many reasons, including patient non-compliance, intolerable adverse effects, and negative effects on treatment response caused by comorbidities and their concomitant medicationsCitation6,Citation7.

Accordingly, TRD is associated with a substantial economic and clinical burden. Recent studies in commercially insured, Medicaid, and Medicare patients have demonstrated significantly higher health care costs among patients with TRD compared to those with non-TRD MDD, with excess costs ranging from $3,385 to $6,709 per-patient-per-year (PPPY) depending on the insurance typeCitation8–10. A recent study estimated a total annual burden of $43.8 billion attributable to TRD among the US populationCitation4. Importantly, health care costs also increase with each trial of therapy; as commercially insured patients progressed from 2 to 6+ lines of therapy of adequate dose and duration, total health care costs PPPY increased by 50% (from $12,047 to $18,667 PPPY)Citation8. Indirect costs associated with TRD have also been evaluated in some studies, with patients with TRD incurring significantly higher rates of disability days and indirect costs compared to those with non-TRD MDDCitation8,Citation11.

Concomitant with this increase in costs, clinical outcomes also worsen with additional lines of treatment. In the landmark Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial, response and remission rates among patients with MDD worsened after non-response to 2 lines of antidepressant treatments and continued to worsen with each subsequent line. Indeed, the remission rate was 31% after 2 lines of therapy, 14% after 3 lines of therapy, and 13% after 4 lines of therapyCitation3,Citation12. Taken together, these findings highlight the importance of achieving a response to treatment in earlier versus later lines of therapy.

Relatedly, adherence and persistence to antidepressant therapy are important to assess, achieve, and maintain therapeutic effectCitation13–15, with about 4–8 weeks typically needed for a conventional antidepressant treatment course to reach its full effectivenessCitation13. A systematic literature review of patients with depressive disorders found that continuing treatment with antidepressants reduced the odds of relapse by 70% compared with treatment discontinuationCitation14. Lack of persistence and treatment discontinuation may be caused by several reasons, including adverse effects, drug-drug interactions from medications used to treat comorbidities, patient perceptions and concerns (e.g. fears of addiction or that antidepressants may alter personality), complicated dosing, lack of follow-up with the clinician, and costCitation16,Citation17.

While treatment persistence does not guarantee a response, understanding the economic implication of achieving persistence on lines of therapy after evidence of TRD may provide insight into the effects of persistence on clinical outcomes. Beyond direct healthcare costs, disability contributes the majority of indirect work loss–related costs in TRDCitation8, and is important to employers who purchase insurance on behalf of their employees. Additionally, depression is a leading cause of disability worldwideCitation18, highlighting the need to assess the association of achieving persistence with this outcome.

Therefore, the current study was conducted to compare health care resource utilization (HCRU), health care costs, and short-term disability days and costs between the following persistence states: (1) evaluation (first 45 days after evidence of TRD), (2) persistence on the early line after evidence of TRD, (3) persistence on a late line, and (4) non-persistence.

Methods

Data source

Patients were identified using the IBM MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Supplemental Databases (January 1, 2013 to March 4, 2019), Multi-State Medicaid Database (January 1, 2013 to December 31, 2018), and Health Productivity Management Database (January 1, 2015 to December 31, 2018).

The Commercial, Medicare Supplemental, and Multi-State Medicaid Databases include medical and prescription drug claims, standard demographic variables (including race in the Multi-State Medicaid database), and monthly information about health plan enrollment. The Commercial database consists of individuals who are covered by employer-sponsored private health insurance and the Medicare Supplemental database profiles retirees with Medicare-Supplemental insurance paid by employers. Both databases cover all US census regions, with concentrations in the South and North Central (Midwest) regions. The Multi-State Medicaid database consists of beneficiaries from 11 states, but the specific states cannot be identified, since this information is not disclosed.

The Health Productivity Management Database includes information on short-term disability days and costs for eligible employees, which is linkable to the corresponding medical and pharmacy data of the employees. The eligibility requirements for short-term disability (e.g. minimum/maximum duration) are set by the individual employers and insurance providers and thus differ across the study sample included. All data are de-identified and comply with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

Study design

A retrospective longitudinal open cohort design was used to identify patients with TRD, and the index date was defined as the date of first observed evidence of TRD (see definition below) during the first observed major depressive episode (MDE; see definition below). Patient characteristics were described during the baseline period, defined as the 12-month period preceding the index date. Outcomes were described and compared during the follow-up period, which spanned from the index date until the earliest of the end of continuous insurance eligibility, the beginning of the next MDE, or end of data availability (March 4, 2019).

Study sample

Patients were included in the study if they met the following inclusion criteria (Supplementary Figure S1): (1) had ≥ 1 claim with a diagnosis for MDD (International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM]: 296.2x, 296.3x; International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM]: F32.xx [excluding F32.8x], F33.xx [excluding F33.8x]) during the most recent period of continuous insurance eligibility; (2) had ≥ 6 months of continuous insurance eligibility before the first MDD diagnosis; (3) had evidence of TRD during the first observed and treated MDE (i.e. the index date); (4) had ≥12 months of continuous insurance eligibility before the index date; and (5) were ≥18 years of age on the index date.

Patients were excluded if they had ≥1 claim with a diagnosis for specific psychiatric illnesses (bipolar disorder, cyclothymic disorder, dementia, mood disorder, psychosis, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, other non-mood psychotic disorders, or substance-induced mood disorder) during the study period, even if they met the inclusion criteria. Additionally, to be included in the sample for the assessment of short-term disability days and costs, patients were required to be eligible to receive short-term disability.

Evidence of TRD

Since there is currently no diagnosis code for TRD, evidence of TRD was identified using an algorithm based on lines of therapy. Evidence of TRD was identified during the first observed MDE in the most recent period of continuous insurance eligibility. The MDE was considered to begin on the date of the first observed MDD diagnosis (preceded by a period of ≥6 months without MDD diagnoses or antidepressant prescription fills) and end on the date of the last MDD diagnosis or the last day of supply of antidepressants (followed by a period of ≥6 months without MDD diagnoses or antidepressant prescription fills), whichever occurred later (Supplementary Figure S2)Citation19. Evidence of TRD was defined as the initiation of a new line of antidepressant therapy of adequate dose following 2 different lines of antidepressant therapy of adequate dose and duration; no restrictions were applied, as long as the active moiety was different in the 2 antidepressant therapies (Supplementary Figure S2). A line of antidepressant therapy comprised either an antidepressant in monotherapy or an antidepressant augmented with another antidepressant or a non-antidepressant augmentation agent. A change of a treatment course of adequate duration included a switch of an antidepressant or an addition of another antidepressant or non-antidepressant augmentation therapy. Adequate duration was defined as having ≥42 days of continuous treatment without gaps of >14 days (based on the average of 4–8 weeks typically required for antidepressant treatment to reach full effectivenessCitation13) Since there is no standard definition of adequate dose, adequate dose (for antidepressants only) was based on the minimum recommended therapeutic dose in the Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire for geriatric and non-geriatric patientsCitation20,Citation21. This definition is consistent with other literature identifying TRD in claims dataCitation22.

Starting with the date of evidence of TRD, subsequent antidepressant therapy trials of adequate dose and any duration were identified within the MDE. The medication trial initiated on the index date (i.e. after evidence of TRD) was defined as the early line of therapy, while all subsequent medication trials were considered late lines of therapy.

Persistence states

Antidepressant therapy persistence states after the index date were used to define study cohorts (Supplementary Figure S3). From the index date, the follow-up period was divided into fixed 45-day increments based on the average of 4–8 weeks typically needed to assess antidepressant effectivenessCitation13 (the duration of the last increment was truncated at the end of follow-up), and persistence state was assessed at the beginning of each increment. Patients could change from one persistence state to another (i.e. open cohort design). The following four states were considered: (1) evaluation: first 45 days after evidence of TRD (or up to 45 days after evidence of TRD for patients with <45 days of available follow-up), a state that was observed once for all patients included in the study; (2) persistence on the early line after evidence of TRD; (3) persistence on a late line after evidence of TRD; and (4) non-persistence after evidence of TRD (i.e. no evidence of persistence during the entire follow-up period).

In analyses of claims data, persistence is typically measured as continuous therapy without a gap in days of therapy supply, with the 30-day gap commonly used for antidepressant therapy in patients with depressionCitation15,Citation23,Citation24. Notably, 30 days is a conservative gap, with other prior studies using gaps of 45 daysCitation25,Citation26. Since these gaps are allowed for all included patients, it likely does not affect the comparative analyses. In our study, reaching persistence was defined as a refill of continuous antidepressant therapy (no gaps in therapy supply >30 days) after the minimum period of adequate duration; a patient with a refill at any time after Day 42 was considered to be persistent as of Day 42. Patients with a diagnosis for MDD in remission (ICD-9-CM: 296.25, 296.26, 296.35, 296.36; ICD-10-CM: F32.4, F32.5, F33.4) were also considered to have reached persistence. Given the observation that remission codes are likely being underutilized (only 8% of the study population had a code for remission in any line of therapy), the association of persistence, remission, and outcomes was not explored in a separate analysis. Patients who discontinued a line of antidepressant therapy after they reached persistence remained in a persistent state until they initiated a new antidepressant therapy trial.

Study outcomes

All-cause HCRU, all-cause health care costs (i.e. medical and pharmacy costs), and short-term disability days and costs were reported per-patient-per-month (PPPM). HCRU included inpatient days, emergency department (ED) visits, outpatient visits, and days with other services (i.e. durable medical equipment and dental or vision care). All-cause health care costs were measured from the payer’s perspective, and health care and short-term disability costs were adjusted for inflation to 2019 US dollars using the medical care component of the US Consumer Price Index.

Statistical analysis

Outcomes were compared between persistence states using multivariate generalized estimating equations (GEEs) models. A univariate model was used to compare days of short-term disability due to sample size-related model non-convergence. The independent variables of interest in the models were the persistence states, with the state of persistence on the early line chosen as a reference. All models were adjusted for repeated measurements on the same patients, and multivariate models were adjusted for baseline covariates (i.e. age, sex, year of index date, race, region, insurance plan/payer type, and Quan-Charlson comorbidity index [Quan-CCI])Citation27.

GEE models with binomial distribution were used to estimate differences in the proportion of patients with ≥1 medical visit. GEE models with Poisson distribution were used to estimate differences in the number of days with all-cause HCRU and short-term disability. GEE models with normal distribution were used to estimate cost differences. Confidence intervals (CIs) and P values in models with Poisson and normal distributions were estimated using a non-parametric bootstrap procedure with 500 replications to account for the overdispersion of the number of days with all-cause HCRU and the non-normal distribution of costs. All analyses were conducted using SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Patient characteristics

Overall, 10,053 patients with TRD were included in the study. The mean age was 37.6 (SD = 15.0) years and 67.6% were female (). The majority of patients (72.0%) were commercially insured, including 2.6% who had Medicare Supplemental coverage, while 25.3% were covered by Medicaid. Among those with race information available (Medicaid data only), 74.3% were white (18.8% of all patients). The majority of patients had diagnoses for behavioral conditions (80.8%), with 65.8% having diagnoses for anxiety, 22.9% for substance use disorders, and 22.4% for reactions to severe stress and adjustment disorders. The most common diagnoses for physical conditions included hypertension (23.8%) and obesity (21.1%). During the baseline period, patients received a mean of 2.4 (SD = 1.0) unique antidepressant agents, and, on average, there were 543 (SD = 320) days between the start of antidepressant therapy and the index date (date on which evidence of TRD was first present). On average, patients incurred $1,123 (SD = $2,621) in PPPM all-cause health care costs during the baseline period, comprising $862 (SD = $2,285) in PPPM medical costs and $262 (SD = $909) in PPPM pharmacy costs.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics for patients with TRD.

Persistence states

Among the 10,053 patients, mean follow-up was 408 days (SD = 337; median = 322; range [minimum; maximum] = 1; 1,888). A total of 3,566 (35.5%) demonstrated persistence on the early line of antidepressant therapy after evidence of TRD, 3,956 (39.4%) demonstrated persistence on a late line, 1,220 (12.1%) demonstrated persistence on both early and late lines, and 3,751 (37.3%) demonstrated non-persistence only. A total of 1,661 (16.5%) patients demonstrated persistence on the early line of therapy and eventually initiated a new antidepressant therapy trial. Among these patients, 535 (32.2%) never demonstrated persistence on late lines of therapy.

On average, time spent in each state was 44 (SD = 7) days for evaluation, 232 (SD = 226) days for persistence on the early line, 315 (SD = 273) days for persistence on a late line, and 215 (SD = 228) days for non-persistence. Time spent in the evaluation state was <45 days for patients with <45 days of available follow-up. Except for the evaluation state, to which all patients contributed one increment, patients could contribute ≥1 increment (or no increment at all) to each persistence state. Overall, 3,566 patients contributed ≥1 increment to the state of persistence on the early line, for a total of 19,311 increments. Similarly, 3,956 and 7,415 patients contributed ≥1 increment to the states of persistence on a late line (number of increments = 29,197) and non-persistence (number of increments = 37,638), respectively.

All-cause HCRU

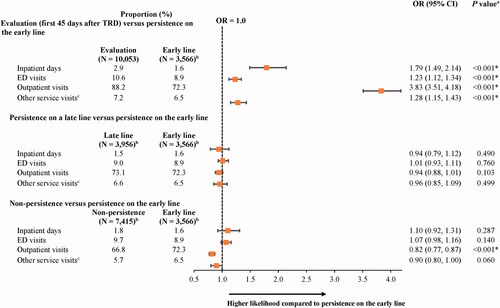

Compared to the state of persistence on the early line, the state of evaluation (i.e. first 45 days after evidence of TRD) was associated with a 79%, 23%, and almost 4 times higher likelihood of ≥1 all-cause inpatient admission (odds ratio [OR; 95% CI] = 1.79 [1.49, 2.14]), ED visit (1.23 [1.12, 1.34]), and outpatient visit, respectively (3.83 [3.51, 4.18]; all p < .001; ). Compared to the state of persistence on the early line, the state of non-persistence was associated with an 18% lower likelihood of ≥1 all-cause outpatient visit (OR [95% CI] = 0.82 [0.77, 0.87]; p < .001). However, no statistically significant differences were observed between the state of persistence on a late line and the state of persistence on the early line.

Figure 1. The proportion of patients with any all-cause HCRU in states of persistence after evidence of TRD relative to persistence on the early line. Abbreviations. CI, confidence interval; ED, emergency department; GEE, generalized estimating equation; HCRU, health care resource utilization; OR, odds ratio; Quan-CCI, Quan-Charlson comorbidity index; TRD, treatment-resistant depression. *Statistically significant at the 5% level. Notes: aORs, CIs, and P values were estimated using GEE models with a binomial distribution and a log link, with adjustments for repeated measurements and baseline covariates (i.e. age, sex, year of index date, race, region, insurance plan/payer type, and Quan-CCI). bPatients may contribute ≥1 increment to the states of persistence on the early line (number of increments = 19,311), persistence on a late line (number of increments = 29,197), or non-persistence (number of increments = 37,638). cOther services include durable medical equipment and dental or vision care.

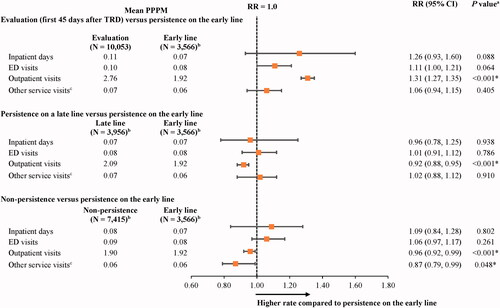

The number of days with all-cause HCRU was similar between the state of persistence on the early line and the other persistence states (i.e. evaluation, persistence on a late line, and non-persistence), with some exceptions related to the number of days with outpatient visits and other services (). Indeed, during the state of evaluation (i.e. first 45 days after evidence of TRD), the mean number of outpatient visits was 31% higher compared to the state of persistence on the early line (RR [95% CI] = 1.31 [1.27, 1.35]; p < .001).

Figure 2. Mean number of all-cause HCRU days in states of persistence after evidence of TRD relative to persistence on the early line. Abbreviations. CI, confidence interval; ED, emergency department; GEE, generalized estimating equation; HCRU, health care resource utilization; Quan-CCI, Quan-Charlson comorbidity index; RR, rate ratio; TRD, treatment-resistant depression. *Statistically significant at the 5% level. Notes: aRRs were estimated using GEE models with a Poisson distribution and a log link, with adjustments for repeated measurements and baseline covariates (i.e. age, sex, year of index date, race, region, insurance plan/payer type, and Quan-CCI). CIs and P values were estimated using a non-parametric bootstrap procedure (N replications = 499). bPatients may contribute ≥1 increment to the states of persistence on the early line (number of increments = 19,311), persistence on a late line (number of increments = 29,197), or non-persistence (number of increments = 37,638). cOther services include durable medical equipment and dental or vision care.

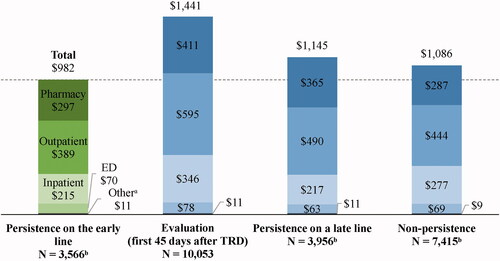

All-cause health care costs

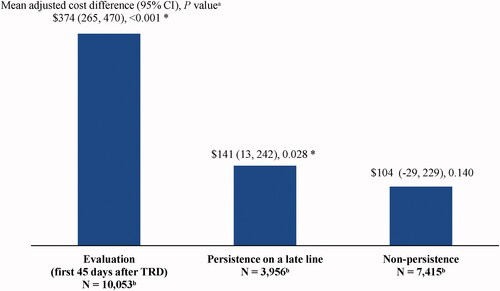

Mean all-cause health care costs for each persistence state are presented in and mean adjusted cost differences in . Mean PPPM all-cause health care costs were $374 higher (adjusted difference; 95% CI = 265, 470; p < .001) during the state of evaluation (i.e. first 45 days after evidence of TRD; unadjusted costs = $1,441) relative to the state of persistence on the early line (unadjusted costs = $982). This mean adjusted cost difference was driven by $164-higher outpatient costs PPPM (95% CI = 121, 208; p < .001), $96-higher inpatient costs PPPM (95% CI = 19, 173; p = .016), and $99-higher pharmacy costs PPPM (95% CI = 75, 123; p < .001) during the state of evaluation compared to the state of persistence on the early line (all differences are adjusted). Moreover, mean PPPM all-cause health care costs were $141 higher (adjusted difference; 95% CI = 13, 242; p = .028) during the state of persistence on a late line (unadjusted costs = $1,145) relative to the early line (unadjusted costs = $982). This mean adjusted cost difference was driven by $81-higher outpatient costs PPPM (95% CI = 27, 133; p = .004) and $38-higher pharmacy costs PPPM (95% CI = 6, 69; p = .012) during the state of persistence on a late line compared to the early line (all differences are adjusted).

Figure 3. All-cause health care costs PPPM after evidence of TRD by each persistence state (2019 USD). Abbreviations. ED, emergency department; PPPM, per-patient-per-month; TRD, treatment-resistant depression; USD, United States dollar. Notes: aOther costs include costs of durable medical equipment and dental or vision care. bPatients may contribute ≥1 increment to the states of persistence on the early line (number of increments = 19,311), persistence on a late line (number of increments = 29,197), or non-persistence (number of increments = 37,638).

Figure 4. Mean monthly adjusted differences in all-cause health care costs after evidence of TRD relative to persistence on the early line. Abbreviations. CI, confidence interval; GEE, generalized estimating equation; Quan-CCI, Quan-Charlson comorbidity index; TRD, treatment-resistant depression. *Statistically significant at the 5% level. Notes: aMean differences were estimated using GEE models with a normal distribution and an identity link, with adjustments for repeated measurements and baseline covariates (i.e. age, sex, year of index date, race, region, insurance plan/payer type, and Quan-CCI). CIs and P values were estimated using a non-parametric bootstrap procedure (N replications = 499). bPatients may contribute ≥1 increment to the states of persistence on the early line (number of increments = 19,311), persistence on a late line (number of increments = 29,197), or non-persistence (number of increments = 37,638).

Short-term disability days and costs

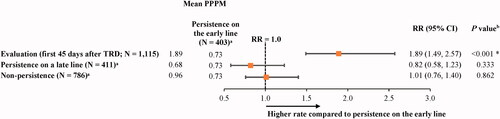

A total of 1,115 patients were eligible to receive short-term disability during the follow-up period. The state of evaluation (i.e. first 45 days after evidence of TRD) was associated with 89% more days with short-term disability relative to the state of persistence on the early line (OR [95% CI] = 1.89 [1.49, 2.57]; p < .001), but no statistically significant differences were observed between the other persistence states (i.e. persistence on a late line and non-persistence) and the state of persistence on the early line ().

Figure 5. Days of short-term disability in states of persistence after evidence of TRD relative to persistence on the early line. Abbreviations. CI, confidence interval; GEE, generalized estimating equation; PPPM, per-patient-per-month; RR, rate ratio; TRD, treatment-resistant depression. *Statistically significant at the 5% level. Notes: aPatients may contribute ≥1 increment to the states of persistence on the early line (number of increments = 2,207), persistence on a late line (number of increments = 2,781), or non-persistence (number of increments = 3,667). bRRs were estimated using GEE models with a Poisson distribution and a log link, with adjustments for repeated measurements. CIs and P values were estimated using a non-parametric bootstrap procedure (N replications = 499).

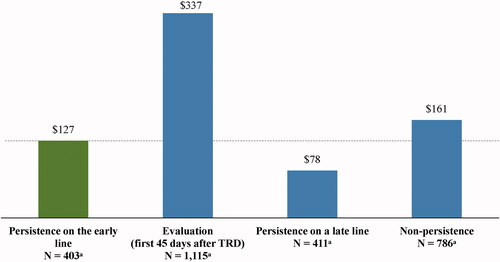

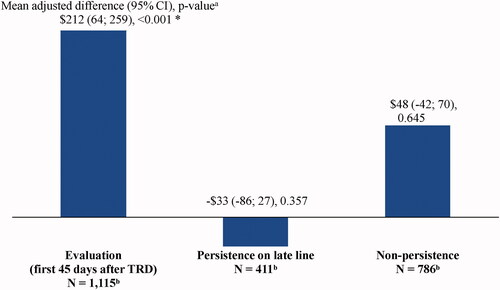

Mean PPPM short-term disability costs were $212 higher (adjusted difference; 95% CI = 64, 259; p < .001) during the state of evaluation (unadjusted costs = $337) relative to the state of persistence on the early line (unadjusted costs = $127), but no statistically significant differences were observed between the other states and the state of persistence on the early line ( and ).

Figure 6. Mean short-term disability costs PPPM after evidence of TRD by each persistence state (2019 USD). Abbreviations. PPPM, per-patient-per-month; TRD, treatment-resistant depression; USD, United States dollar. Note: aPatients may contribute ≥1 increment to the states of persistence on the early line (number of increments = 2,207), persistence on a late line (number of increments = 2,781), or non-persistence (number of increments = 3,667).

Figure 7. Mean monthly adjusted differences in short-term disability costs after evidence of TRD relative to persistence on the early line. Abbreviations. CI, confidence interval; GEE, generalized estimating equation; Quan-CCI, Quan-Charlson comorbidity index; TRD, treatment-resistant depression. *Statistically significant at the 5% level. Notes: aMean differences were estimated using GEE models with a normal distribution and an identity link, with adjustments for repeated measurements and baseline covariates (i.e. age, sex, year of index date, race, region, insurance plan/payer type, and Quan-CCI). CIs and P values were estimated using a non-parametric bootstrap procedure (N replications = 499). bPatients may contribute ≥1 increment to the states of persistence on the early line (number of increments = 2,207), persistence on a late line (number of increments = 2,781), or non-persistence (number of increments = 3,667).

Discussion

This study demonstrated that patients with TRD incurred higher all-cause HCRU, all-cause health care costs, and short-term disability days and costs during the state of evaluation (i.e. first 45 days after evidence of TRD) compared to the subsequent state of persistence on the early line of antidepressant therapy. This suggests that there may be economic benefits associated with selecting an antidepressant on which patients will persist and that these benefits may go beyond direct health care costs, as demonstrated by the reduced short-term disability days and costs during the state of persistence on the early line of antidepressant therapy. Indeed, disability comprised 82% of indirect work loss–related costs in one study of privately insured patients with TRD, highlighting the substantial work loss burden in this primarily working-age populationCitation8.

Reaching persistence on late lines of antidepressants in this study was associated with higher health care costs compared to reaching persistence on the early-line therapy, mainly due to higher outpatient and pharmacy costs. Thus, the additional medical visits and costs associated with initiating a new line of treatmentCitation8,Citation28 suggest that persistence to the early line of therapy may offer clinical and economic benefits as well as reduce the need for later lines. To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the economic implications of reaching persistence on the late versus early antidepressant intervention among patients with TRD. Relatedly, prior studies demonstrated high HCRU and costs associated with TRD compared to non-TRD MDDCitation8–10, with costs increasing with each trial of antidepressant therapyCitation8. Together with this literature, the current findings emphasize the need for early identification of effective interventions and long-term maintenance strategies that encourage treatment persistence among patients with TRDCitation6.

In this study, 37.3% of patients never reached persistence on an antidepressant therapy after evidence of TRD. This observation aligns with the general finding in the literature that adherence and persistence are difficult to achieve in the MDD populationCitation15. For instance, in a study of US Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) data, 42% of patients discontinued antidepressant therapy during the first 30 days and 72% discontinued it after 90 daysCitation29. Reasons for non-persistence may vary, but it is likely that patients who do not remain on any antidepressant therapy long enough for it to achieve a treatment effect may not experience an improvement in symptoms. Interestingly, non-persistence was associated with a lower likelihood and number of outpatient visits compared to the state of persistence on the early line in the current study, which may suggest less regular and consistent health care to proactively manage TRD and other potential health conditions in general among patients who do not persist on antidepressant therapy.

One factor contributing to non-persistence may be the large comorbidity burden associated with TRD, including anxiety disorders, substance use disorders, and cardiovascular and metabolic diseasesCitation7,Citation30. The presence of comorbid conditions and their respective treatments may represent a challenge for the integration of antidepressant therapy, especially augmented with non-antidepressant agents, such as atypical antipsychotics, into already complex treatment regimens. For instance, potential drug-drug interactions may interfere with tolerability and responseCitation6,Citation16,Citation31, and patients with several comorbidities may have poorer adherenceCitation32. In addition, patients with depression and comorbid substance use disorders are less likely to be treated for depression compared to those without comorbid substance use disordersCitation33. In the current study, many patients had diagnoses for behavioral (80.8%) and/or physical conditions (49.9%), including anxiety (65.8%), substance use disorders (22.9%), and metabolic diseases (33.3%), potentially contributing to the low persistence observed after TRD. Of note, approximately one-third of patients who persisted on the early line of therapy and eventually initiated a new antidepressant therapy trial were unable to achieve persistence on late lines of therapy. This suggests that after persisting on the early line, achieving persistence on later lines may be difficult.

Achieving treatment persistence has important clinical implications, as the risk of relapse/recurrence is associated with treatment duration. Continuing treatment with antidepressants reduces the odds of relapse by 70% compared with treatment discontinuation in patients with depressive illnessCitation14. Importantly, standard antidepressants usually require at least 1 month for effects to manifestCitation34, so early discontinuation may not allow for sufficient exposure for the medication to exert a therapeutic effectCitation35. Further emphasizing the importance of persisting on early lines of therapy are the findings of the STAR*D clinical trial, which established that response rates are lower with each subsequent treatment lineCitation3,Citation12. In fact, remission rates decreased from 37% after the first line to 13% after the fourth line. Together with the literature, the current study suggests that identifying effective treatments and initiating them early in patients with TRD may result in better persistence, and, consequently, better treatment and economic outcomes. Notably, in patients with comorbidities, adherence to antidepressant therapy is associated with increased adherence to medications taken for the management of comorbidities and may reduce costsCitation36, demonstrating the compounding effect of persisting on antidepressant therapy.

Limitations

The findings of this study should be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, since the study included patients with commercial, Medicare Supplemental, or Medicaid coverage, the results may not be representative of patients without health insurance. Second, diagnoses that are reported in claims databases are for administrative purposes and may not accurately reflect any working diagnosis or descriptions of symptom clusters contained in treatment records; therefore, some mental health diagnoses in administrative databases may be underreported or modified in part due to social stigma, or otherwise not consistently reflect the actual condition. Relatedly, although the first observed MDE in the most recent continuous insurance eligibility period was identified, it is possible that patients had other MDEs in prior eligibility periods. In addition, although the minimum dosages for antidepressants were identified for the definition of adequate dose and duration, there is a possibility of variabilities of dosages in both what is prescribed and what is actually taken. Samples used to initiate a branded product or medications dispensed over the counter were not captured in the database. Finally, the results of this study may be confounded due to unobserved factors that were not accounted for in the multivariate models.

Conclusions

Increased all-cause HCRU, all-cause health care costs, and short-term disability days and costs during the first 45 days after evidence of TRD compared to the subsequent state of persistence on the early line of antidepressant therapy suggest that it may be beneficial to select an antidepressant on which patients can persist earlier in the course of treatment. Moreover, given that persistence on late lines of antidepressant therapy after evidence of TRD is associated with higher all-cause health care costs relative to the early line, using antidepressant treatments, on which patients are more likely to respond and persist, earlier in the course of TRD may optimize treatment outcomes and offer economic gains in patients with TRD, especially if later lines of therapy are no longer required.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Financial support for this research was provided by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. The study sponsor was involved in several aspects of the research, including the study design, the interpretation of data, the writing of the manuscript, and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Declaration of financial/other interests

DP, MZ, ACS, AS, and PL are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, which funded the development and conduct of this study and manuscript. SK, JJS, OJL, and KJ are employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC and stockholders of Johnson & Johnson. LC reports paid consulting for AbbVie, Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, Angelini, Astellas, Avanir, Axsome, BioXcel, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cadent Therapeutics, Eisai, Impel, Intra-Cellular Therapies, Janssen, Karuna, Lundbeck, Lyndra, Medavante-ProPhase, Merck, Neurocrine, Noven, Otsuka, Ovid, Relmada, Sage, Sunovion, Teva, University of Arizona, and one-off ad hoc consulting for individuals/entities conducting marketing, commercial, or scientific scoping research; speaker for AbbVie, Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, Angelini, Eisai, Intra-Cellular Therapies, Janssen, Lundbeck, Neurocrine, Noven, Otsuka, Sunovion, Takeda, Teva, and CME activities organized by medical education companies such as Medscape, NACCME, NEI, Vindico, and Universities and Professional Organizations/Societies; stocks in Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, J & J, Merck, Pfizer; and royalties from Wiley (Editor-in-Chief, International Journal of Clinical Practice, through end 2019), UpToDate (reviewer), Springer Healthcare (book), and Elsevier (Topic Editor, Psychiatry, Clinical Therapeutics).

A reviewer on this manuscript has disclosed they hold/held equity in Matrix45 and its predecessor The Epsilong Group, which has had research and consulting contracts with Janssen Scientific Affairs (US), as well as other divisions of Johnson & Johnson (worldwide). It is company policy, that employees cannot hold equity in sponsor organizations, nor perform services and/or receive compensation independently from sponsor organizations. The other peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Author contributions

DP, MZ, ACS, AS, and PL contributed to study conception and design, collection and assembly of data, and data analysis and interpretation. SK, JJS, OJL, KJ, and LC contributed to study conception and design, data analysis and interpretation. All authors reviewed and approved the final content of this manuscript.

Previous presentation

Part of the material in this manuscript was presented at the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMCP) Meeting held virtually on April 12–16, 2021 as a poster presentation.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (77.4 KB)Acknowledgements

Medical writing support was provided by a professional medical writer, Christine Tam, an employee of Analysis Group, Inc.

References

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2019 national survey on drug use and health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2020; :1–114.

- Al-Harbi KS. Treatment-resistant depression: therapeutic trends, challenges, and future directions. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:369–388.

- Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. AJP. 2006;163(11):1905–1917.

- Zhdanava M, Pilon D, Ghelerter I, et al. The prevalence and national burden of treatment-resistant depression and major depressive disorder in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry. 2021;82(2):20m13699.

- United States Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves new nasal spray medication for treatment-resistant depression; available only at a certified doctor’s office or clinic 2019. [cited 2021 June 14]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-nasal-spray-medication-treatment-resistant-depression-available-only-certified

- Parikh RM, Lebowitz BD. Current perspectives in the management of treatment-resistant depression. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2004;6(1):53–60.

- Voineskos D, Daskalakis ZJ, Blumberger DM. Management of treatment-resistant depression: challenges and strategies. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2020;16:221–234.

- Amos TB, Tandon N, Lefebvre P, et al. Direct and indirect cost burden and change of employment status in treatment-resistant depression: a matched-cohort study using a US commercial claims database. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(2):17m11725.

- Pilon D, Joshi K, Sheehan JJ, et al. Burden of treatment-resistant depression in Medicare: a retrospective claims database analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14(10):e0223255.

- Pilon D, Sheehan JJ, Szukis H, et al. Medicaid spending burden among beneficiaries with treatment-resistant depression. J Comp Eff Res. 2019;8(6):381–392.

- Ivanova JI, Birnbaum HG, Kidolezi Y, et al. Direct and indirect costs of employees with treatment-resistant and non-treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(10):2475–2484.

- Sinyor M, Schaffer A, Levitt A. The sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression (STAR*D) trial: a review. Can J Psychiatry. 2010;55(3):126–135.

- American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder: 3rd edition 2010. [September 18, 2019]. Available from: https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf

- Geddes JR, Carney SM, Davies C, et al. Relapse prevention with antidepressant drug treatment in depressive disorders: a systematic review. Lancet. 2003;361(9358):653–661.

- Keyloun KR, Hansen RN, Hepp Z, et al. Adherence and persistence across antidepressant therapeutic classes: a retrospective claims analysis among insured US patients with major depressive disorder (MDD). CNS Drugs. 2017;31(5):421–432.

- Citrome L, Johnston S, Nadkarni A, et al. Prevalence of pre-existing risk factors for adverse events associated with atypical antipsychotics among commercially insured and Medicaid insured patients newly initiating atypical antipsychotics. Curr Drug Saf. 2014;9(3):227–235.

- Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Antidepressant adherence: are patients taking their medications? Innov Clin Neurosci. 2012;9(5–6):41–46.

- Ferrari AJ, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, et al. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS Med. 2013;10(11):e1001547.

- Wu B, Cai Q, Sheehan JJ, et al. An episode level evaluation of the treatment journey of patients with major depressive disorder and treatment-resistant depression. PLoS One. 2019;141(8):e0220763.

- Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire (ATRQ), Non-Geriatric Population, version 2. 2015.

- Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire (ATRQ), Geriatric Population, version 3. 2016.

- Zhdanava M, Karkare S, Pilon D, et al. Prevalence of pre-existing conditions relevant for adverse events and potential drug-drug interactions associated with augmentation therapies among patients with treatment-resistant depression. Adv Ther. 2021;38(9):4900–4916.

- Adhikari K, Patten SB, Lee S, et al. Adherence to and persistence with antidepressant medication during pregnancy: does it differ by the class of antidepressant medication prescribed? Can J Psychiatry. 2019;64(3):199–208.

- Ereshefsky L, Saragoussi D, Despiegel N, et al. The 6-month persistence on SSRIs and associated economic burden. J Med Econ. 2010;13(3):527–536.

- Kim-Romo DN, Rascati KL, Richards KM, et al. Medication adherence and persistence in patients with severe major depressive disorder with psychotic features: antidepressant and second-generation antipsychotic therapy versus antidepressant monotherapy. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(5):588–596.

- Solem CT, Shelbaya A, Wan Y, et al. Analysis of treatment patterns and persistence on branded and generic medications in major depressive disorder using retrospective claims data. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:2755–2764.

- Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Medical Care. 2005;43(11):1130–1139.

- Johnston KM, Powell LC, Anderson IM, et al. The burden of treatment-resistant depression: a systematic review of the economic and quality of life literature. J Affect Disord. 2019;242:195–210.

- Olfson M, Marcus SC, Tedeschi M, et al. Continuity of antidepressant treatment for adults with depression in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):101–108.

- Zhdanava M, Kuvadia H, Joshi K, et al. Economic burden of treatment-resistant depression in privately insured U.S. patients with physical conditions. JMCP. 2020;26(8):996–1007.

- Culpepper L. Managing depression and medical comorbidities. Postgrad Med. 2003;114(5 Suppl Treating):26–38.

- Roca M, Armengol S, García-García M, et al (editors). Adherence to antidepressant treatment in depressive patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders. 19th European Congress of Psychiatry; 2011. European Psychiatry.

- Han B, Olfson M, Mojtabai R. Depression care among depressed adults with and without comorbid substance use disorders in the United States. Depress Anxiety. 2017;34(3):291–300.

- Machado-Vieira R, Salvadore G, Luckenbaugh DA, et al. Rapid onset of antidepressant action: a new paradigm in the research and treatment of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(6):946–958.

- Solmi M, Miola A, Croatto G, et al. How can we improve antidepressant adherence in the management of depression? A targeted review and 10 clinical recommendations. Braz J Psychiatry. 2021;43(2):189–202.

- Katon W, Cantrell CR, Sokol MC, et al. Impact of antidepressant drug adherence on comorbid medication use and resource utilization. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(21):2497–2503.