?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Aims

To estimate the cost of antiviral medication guidance and/or support from the perspective of healthcare professionals by administration route (oral or inhalant).

Methods

An online survey (December 2020) was conducted among physicians, pharmacists, and certified care workers. Those aged 20–64 years working in workplaces with experience of prescribing (physicians) or dispensing (pharmacists) antivirals for influenza, or having care service recipients who took antivirals (certified care workers) since October 2018, were selected through screening questions. The time required for guidance and/or support for drug administration was asked, and its monetary value was calculated by applying the Japanese average wage. Respondents who had a fear of infection while providing guidance and/or support were asked about the monetary value of this fear; the cost of fear was estimated from their responses and the percentage who reported such a fear.

Results

Responses were collected from 1,000 physicians, 1,000 pharmacists, and 642 certified care workers. The cost of the time for guidance and/or support in the entire workplace was estimated as JPY 244 (USD 2.14, as of October 2021) for oral antivirals and JPY 289 for inhalants among physicians, JPY 260 and JPY 428 among pharmacists, and JPY 555 and JPY 557 among certified care workers. The cost of fear was estimated to be JPY 965 for oral and JPY 1,361 for inhalants among physicians, JPY 756 and JPY 2,711 among pharmacists, and JPY 2,419 and JPY 2,837 among certified care workers.

Limitations

Respondents might not be representative of Japanese society. The reliability of the results depends on whether the respondents accurately understood the questions and their truthfulness.

Conclusions

Higher costs for guidance and/or support were suggested for inhalant antivirals in physicians and pharmacists compared to oral antivirals. For certified care workers, almost no difference in costs was suggested between administration routes.

Introduction

In Japan, the influenza epidemic affected a reported 22.1 million in the 2017/18 season, 11.7 million in the 2018/19 season, and 7.3 million in the 2019/20 seasonCitation1. Healthcare professionals (HCPs) such as physicians, pharmacists, and certified care workers provide medical care to influenza patients and run the risk of getting infected. Since the coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic began, HCPs need to consider the possibility of both influenza and COVID-19, because both infectious diseases are indistinguishable by their symptomsCitation2.

In Japan, baloxavir marboxil (baloxavir) was approved in February 2018 for influenza treatment, followed by the generic drug oseltamivir in June 2018. Since the 2018/19 season, five brand-name antivirals and the generic oseltamivir have been made available. There are multiple administration routes for antivirals: oral (oseltamivir and baloxavir), inhaled (zanamivir and laninamivir), and intravenous (peramivir). In addition, the duration and frequency of the treatment are different; baloxavir, laninamivir, and peramivir are administered once, while oseltamivir and zanamivir are administered twice daily for five days. Physicians can choose a suitable antiviral agent for each influenza patient. However, Japanese clinical guidelines for managing influenza for the 2020/21 season mentioned that the use of inhaled antivirals could cause patients to cough; therefore, adequate infection control was requiredCitation3.

We have already reported differences in the monetary values of patient convenience among antivirals approved in JapanCitation4. In this study, we aim to evaluate the differences in the values of approved antivirals from the perspective of HCPs. First, we assume that HCPs spend different lengths of time when prescribing, dispensing, or supporting influenza patients to take antivirals depending on the administration route. Second, we assume that HCPs have different levels of fear of getting infected during guidance and/or support related to antiviral medication for influenza patients depending on the administration route. We deduced that the length of time and the level of fear are costs for HCPs, which have not been examined by any previous study.

As part of this study, we conducted a questionnaire survey among HCPs regarding their recent experiences of prescribing, dispensing, and supporting influenza patients on taking antivirals in two seasons (2018/19 and 2019/20) in Japan. Thus, we evaluated the situation in which HCPs treated influenza patients with antivirals and revealed the differences in the costs of HCPs based on the administration routes of antivirals.

Methods

Study design

We conducted an online survey to understand the status of prescribing, dispensing, or supporting influenza patients taking antivirals, and the monetary value of fear, or to eliminate the fear of infection, during guidance and/or support for drug administration by type of administration route: oral or inhalant. We reflected on basic items that should be considered when applying a contingent valuation method to evaluate healthcare servicesCitation5 when developing the questionnaire. Based on the survey results, we estimated the cost of the time for guidance and/or support for drug administration and the cost of fear with guidance and/or support in HCPs per instance. We discussed the results with experts in each occupation, who had experience and knowledge of the occupations, to assist with the interpretation.

Online survey

The online survey was conducted in December 2020. Two online panels were used in the study. One included physicians and pharmacists managed by M3, Inc. (Tokyo, Japan), and the other included certified care workers managed by INTAGE Inc. (Tokyo, Japan). These panels comprised individuals who had registered as members willing to participate in online surveys in advance. We planned to include 1,000 respondents each for physicians and pharmacists, and 750 for certified care workers after considering the number of individuals in each occupation in the panels as well as the research budget.

At the beginning of the survey, an invitation was sent to randomly selected physicians and pharmacists, regardless of their attributes, and to all certified care workers in the panels. The respondents who agreed to participate in the survey answered the screening questions, and the respondents for the main survey were selected based on these answers. The invitations were sent to a certain number of individuals, and the answers were accepted until the planned number of respondents was gathered for the main survey for physicians and pharmacists. Therefore, all eligible respondents selected through the screening questions were included as respondents in the main survey.

The eligible respondents for the main survey were aged 20–64 years. Each of the respondents’ workplaces had experience with prescribing (physicians) or dispensing (pharmacists) antivirals for influenza or had care service recipients who took antivirals (certified care workers) since October 2018. We excluded dry syrup and intravenous infusion, which are also available for influenza treatment, as such a patient’s profile was considered to be different from that of general patients—dry syrup is mainly used for infants and children, and an intravenous infusion is for hospitalized patients or those with difficulty in oral ingestion. Antivirals for prevention and inpatient treatment were excluded. The questions are listed in Supplementary Material Table S1. Information regarding these attributes was also collected.

Table 1. Question types and sentences to ask the monetary value for fear during guidance and/or support by type.

The main survey comprised questions on the experience of guidance and/or support for antiviral drug administration and the time required for it. The main survey also contained questions about fear of infection and its equivalent monetary value during guidance and/or support (Table S1). When asking about these experiences, we used the same expression “guidance and/or support for drug administration” in the questions for all occupations, with explanatory sentences to define the expression. Explanations included: “It means those actions such as to explain the beneficial effects and side effects of the drug to a patient, to let a patient take the drug on the spot and watch it, to confirm that a patient intakes the drug, and so on.” We asked the respondents what percentage of patients they gave guidance and/or support out of the overall number of patients they prescribed (physicians) or dispensed (pharmacists) with antivirals for influenza, or the overall number of their care recipients who took antivirals (certified care workers).

Information on the time required for guidance and/or support per patient by administration route was gathered. The required time was (1) by respondents and (2) in the entire workplace, including time contributed by other occupations. If the respondents did not have the requisite experience, they were asked to imagine their colleagues’ experiences (with the same occupation) in their workplace to answer the questions. The certified care workers were also asked about their experience with guidance and/or support for patients with dementia.

Next, we asked about the respondent’s own experience with providing guidance and/or support for antiviral drug administration and asked if they feared getting infected by patients while providing guidance and/or support. For respondents who stated that they did have a fear of infection, we asked them the different monetary values of their fear by administration route. We anticipated that the value would depend on how the question was phrased. Therefore, we prepared four types of questions: combinations of willingness to pay (WTP) type or value evaluation type, and direct or two-step method (). The respondents were randomly assigned one of the four types of questions, all of which allowed them to state any value amount (open-ended method).

Initially, we considered asking them the value directly, because they were providing guidance and/or support by themselves and could evaluate it. However, it is possible that people may evaluate their own work more highly than others do. Bearing this in mind, we prepared the questions according to WTP, originally used in the field of environmental assessmentCitation6,Citation7 and more recently used to evaluate health policy and health technology for remuneration decisionsCitation5,Citation8,Citation9. Despite the question types differing, all questions inquired about the value of the same aspects. Thus, the values should be the same regardless of the type of question. If the values were considerably different between the question types, the true value may be considered the mean value of both question types. However, we decided to prioritize the answers to questions of the value evaluation type because this survey is not to decide remuneration. The two-step method, defined as asking for the total value of guidance and/or support with fear first and then asking about the part of fear, was also set for each type of question. This is because we considered that answering the monetary value on the feeling of fear, separated from the behavior of guidance and/or support, might be difficult for respondents to do accurately.

Statistical analysis

We tabulated the answers by type of respondents’ occupation and further divided them into subgroups according to their attributes. We confirmed the representativeness of each occupation group based on their attributes. To estimate the cost of guidance and/or support for antiviral drug administration per guidance and/or support, we first calculated the mean required time for guidance and/or support by the respondents themselves and for the entire workplace, based on answers from the respondents. We excluded those who answered “not sure” about the percentage of patients given guidance and/or support by the respondents themselves. Next, we estimated the cost by applying the mean required time in the entire workplace, not by the respondents themselves, because we considered that guidance and/or support was provided by various occupations besides the respondents’ occupations. The cost was calculated as follows:

where mean required time is obtained in this study, the average wage is that across all industries, all ages, and both gendersCitation10, and average working time is for enterprises with ≥30 peopleCitation11. We applied the same average wage for all occupations as the time for an entire workplace could include various occupations, such as nurses, office clerks, and so on.

The cost of fear was estimated by applying the percentage of respondents who acknowledged that they feared infection during guidance and/or support to the monetary value of fear from the results of the survey. This estimation is based on a conservative assumption that the monetary value of fear is zero for those who do not feel fear. First, the monetary value of fear from the results of the survey was calculated for each of the four types of questions with mean and quartile values. Next, one of the four question types was chosen, and its monetary value was applied to calculate the cost of fear in each occupation by administration route.

We further calculated the total costs of treatment for each available brand and generic anti-influenza drug in Japan, including drug costCitation12,Citation13, the intangible costs for patients reported in a previous studyCitation4, and the costs for HCPs from this study, to support an interpretation of the results. In this calculation, the intangible costs for patients contained the value of convenience and productivity lossCitation4. The costs for HCPs included the estimated cost of guidance and/or support and the cost of fear of infection for physicians and pharmacists. The costs for certified care workers were excluded from this calculation because the previous study did not include patients aged ≥65 years. We applied the Grubbs–Smirnov test to identify outliers and excluded respondents with < 0.01 as an outlier. Microsoft Excel 2016 (Microsoft, Redmond, MA, USA) was used for the analyses.

Ethics approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines for medical and health research involving human subjects by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology and the Ministry of Health, Labour and WelfareCitation14. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Research Institute of Healthcare Data Science (RI2020018) and registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network Clinical Trial Registry (UMIN000042606). We explained to the respondents the purpose of using the results and content of information obtained from them, and that they could quit the survey at any time. Thereafter, we acquired consent from all respondents at the beginning of the survey.

Results

Respondents

We initially collected answers from 2,367 physicians, 1,460 pharmacists, and 6,257 certified care workers. The mean (standard deviation [SD]) age and percentage of men were 49.7 (14.6) years and 90.1% for physicians (), 45.7 (14.4) years and 63.2% for pharmacists (), and 46.2 (9.1) years and 33.4% for certified care workers (). The percentages of respondents by type of facility, type of employment, and type of services provided are shown in , respectively. The attributes of the respondents are listed in . Among these, 1,000 physicians, 1,000 pharmacists, and 642 certified care workers were selected as respondents for the main survey. Of the respondents, those who had experience with prescribing (for physicians) or dispensing (for pharmacists) antivirals on their own, or having their own care service recipients who took antivirals (for certified care workers) for influenza in their current workplaces were 95.1%, 96.3%, or 74.8%, respectively.

Table 2. Characteristics of respondents (overall): physicians.

Table 3. Characteristics of respondents (overall): pharmacists.

Table 4. Characteristics of respondents (overall): certified care workers.

Current status of prescription/dispensing/taking antivirals in workplaces

The percentage of respondents whose workplace had experience with prescribing (for physicians) or dispensing (for pharmacists) antivirals, or having care service recipients who took antivirals (for certified care workers) for influenza was 87.1%, 93.2%, and 31.4%, respectively. Among the types of services provided by certified care workers, long-term care facilities showed relatively high percentages (approximately 40%−50%) ().

Required time and estimated cost of time for guidance and/or support for antiviral drug administration

In response to the question regarding the percentage of patients who were provided with guidance and/or support for antiviral drug administration by the respondents themselves (or other colleagues with the same occupation as the respondents), the number of respondents by percentage in each occupation is shown in . From the results, excluding those who answered “not sure,” the mean percentages of physicians, pharmacists, and certified care workers were 70.1%, 81.6%, and 64.5%, respectively.

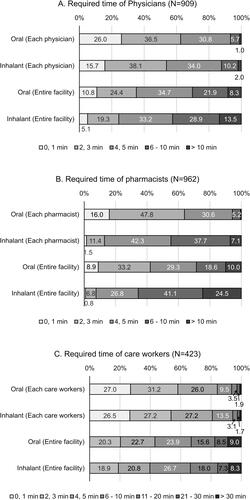

The mean time required to provide guidance and/or support per patient in their workplace was shortest among physicians followed by pharmacists, and then by certified care workers, which was almost double that of physicians (). By occupation, inhalants required a longer time for pharmacists and physicians, which was 3.5 min longer for pharmacists than for oral drugs. In contrast, almost no difference was observed between inhalants and oral drugs for certified care workers. As for the percentage of respondents per occupation, approximately 90% of physicians took ≤5 min for both oral and inhalant drugs (). Approximately 95% of pharmacists took ≤5 min for oral administration, while approximately 55% of pharmacists took ≤5 min for inhalants (). No remarkable difference was observed between the types of administration routes for certified care workers ().

Figure 1. Percentage of respondents by required time for guidance and/or support for drug administration among physicians (A), pharmacists (B), and certified care workers (C).

Table 5. Required time for guidance and/or support for drug administration.

We estimated the cost of guidance and/or support based on the mean required time (). The estimated costs in the workplaces were JPY 244 for oral antivirals and JPY 289 for inhalants among physicians, JPY 260 and JPY 428 among pharmacists, and JPY 555 and JPY 557 among certified care workers (JPY 1 = US dollar 0.009, as of October 2021).

When comparing the time between the types of workplaces of physicians, hospitals required more time than clinics. However, the time for physicians themselves was not very different (). Workers at affiliated hospitals of medical educational institutions, regardless of their type of employment, answered with a relatively long time. Considering the relationship between the type of workplace and internal/external prescription, approximately 70% of those working in hospitals (not including affiliated hospitals of medical educational institutions) answered that the hospital had experience with internal prescriptions (). Meanwhile, only external prescription experiences were common (approximately 60%) in clinics.

Table 6. Required time for guidance and/or support for drug administration by type of facilities and type of employment (physicians).

Regarding the type of workplace for pharmacists, no remarkable differences were observed for the pharmacists themselves. However, pharmacists in hospitals and clinics reported a longer time than their pharmacy-based counterparts for the entire workplace ().

Table 7. Required time for guidance and/or support for drug administration by type of facilities and type of employment (pharmacists).

Among the certified care workers’ workplaces, the mean required time varied for both the certified care workers themselves (4.0–17.3 min) and entire workplaces (8.7–33.2 min) (). The difference in required time between administration routes depended on the type of the facility, and some of the facilities showed a longer mean required time for oral antivirals than for inhalants ().

Table 8. Required time for guidance and/or support for drug administration by type of services (certified care workers).

We further examined the difference in time for care recipients between those with and without dementia. For those with dementia, the required time for certified care workers was 6.1 min for oral and 6.5 min for inhalant treatments. For the entire workplace, it was 18.6 and 17.5 min, respectively. The time was longer than for those without dementia; the difference in time was approximately 1 min for both routes for certified care workers and 2.5 and 1.4 min for oral and inhalant routes for the entire workplace.

Existence of fear of infection and estimated cost of fear

The percentage of respondents who answered that they “feel fear of infection from patients during guidance and/or support for antiviral drug administration” for oral drugs was 87.7%, 70.5%, and 83.3% for physicians, pharmacists, and certified care workers, respectively. Likewise, for inhalants, it was 99.7%, 99.8%, and 83.9%, respectively.

For the respondents who answered that they felt fear, the monetary value for fear of infection was tabulated by question type and occupation ( and ). Note that the answers from one certified care worker were excluded as outliers. In all types of occupations, the monetary value was higher in the value evaluation type questions (Type B or D) than in the WTP type (Type A or C). Moreover, the value was lower in the two-step method (Type C or D) than in the direct method (Type A or B). Regardless of the question type, the values suggested by certified care workers were two or three times higher than those by physicians or pharmacists. The mean value for fear tended to be higher for inhalants than for oral, regardless of the type of question in all occupations. The difference between administration routes was the highest among pharmacists, and lowest for certified care workers.

Table 9. Monetary value for fear of infection.

To estimate the cost of fear, we chose the monetary value obtained from the Type D question, as described later in the discussion. The cost of fear was calculated to be JPY 965 for oral and JPY 1,361 for inhalants among physicians, JPY 756 and JPY 2,711 among pharmacists, and JPY 2,419 and JPY 2,837 among certified care workers.

Total costs of treatment for each antiviral

The total costs of treatment, including drug cost, the intangible costs for patients (value of convenience and productivity loss) in a previous studyCitation4, and the costs for HCPs (for guidance and/or support and fear of infection) from this study, were the lowest for baloxavir and the highest for zanamivir among all available anti-influenza drugs in Japan ().

Table 10. Estimated treatment cost of available antivirals in Japan.

Discussion

We estimated the cost of guidance and/or support for antiviral drug administration, by type of administration route and occupation, using an online survey. The cost of the time for guidance and/or support was estimated to be JPY 244 for oral and JPY 289 for inhalant for the entire workplace of physicians, JPY 260 and JPY 428 for that of pharmacists, and JPY 555 and JPY 557 for that of certified care workers (). The monetary value of the fear of infection during guidance and/or support was assessed using four question types, and the value varied among the question types ().

Regarding the validity of this study, we considered the basic types of validity for quantitative research. We also confirmed external validity by comparing the distributions of some of the attributes of this study’s participants to those nationwide in each occupationCitation15,Citation16. As a result, although there were some differences between the study participants and the population in each occupation, we considered external validity to be secured to a certain extent within the country. Physicians in their 50 s and those working in hospitals were oversampled in this study population compared with nationwide distributions. The higher male percentage (91%) was similar to that in physicians nationwide (78.1%), although the percentage itself was higher in our study. No significant difference was observed in the distribution by department (). Regarding pharmacists, this study included more pharmacists in their 40 s and those working in hospitals (). Among certified care workers, those working in workplaces with outpatient-type care services were more represented and those working in those with home-visit care services were less represented compared with those nationwide ().

Regarding external validity outside the country, we deduced that the differences in the healthcare system and healthcare financing, as well as income and living expenses between countries, could impact the results in this study. Therefore, external validities might be secured only within the country. Even so, the content of each professional job might not be much different compared with those between countries; consequently, the required time itself might be applicable for other countries and regions of the world.

The longer required time for the entire workplace of certified care workers compared with that of physicians and pharmacists might be reasonable when considering the characteristics of each occupation. Assisting with medication is not always permitted for certified care workers, as it depends on the condition of patients and requires other HCPs with appropriate certifications in medical practiceCitation17. Therefore, a longer time taken at the workplace is reasonable when considering the time taken by other health occupations.

Regarding the required time for certified care workers themselves, an expert indicated that the support for drug administration includes various actions: explaining and convincing patients to take the drugs, making the drugs easier to take, and observing patients until the consumption of the drugs was completed. A survey among certified care workers indicated that 88% felt anxious due to their lack of basic knowledge about medication, and reported some major issues when supporting antiviral drug administration in nursing homes, including dropping a medication, administering medication to the wrong patient, refusal from patients to take medication, and confusionCitation18. Considering these factors, a longer time may be required in the workplaces of certified care workers than in those of physicians and pharmacists. There was almost no difference between administration routes in answers by certified care workers, probably because the aforementioned actions for support are required for both oral and inhalant drugs, which is likely to take up the majority of the time. Additionally, according to an expert’s suggestion and a bulletin of a group of medical institutionsCitation19, certified care workers crush or thicken drugs to make it easy for elderly care service recipients to take oral drugs, contributing to prolonged oral drug administration.

The time required for guidance and/or support was not very different between care service recipients with and without dementia. An expert suggested that certified care workers frequently interacting with patients with dementia were familiar with their support. Consequently, dementia may not be a cause for extending the time.

In the workplaces of physicians and pharmacists, inhalants required a longer time for guidance and/or support than oral antivirals. This can be considered reasonable, because detailed instruction on the correct way of inhalation is important to obtain therapeutic effectsCitation20,Citation21, requiring a longer time for guidance compared with oral drugs. A survey study indicated an easiness with shorter required time for guidance in oral drug among oseltamivir (including both capsule and dry syrup), zanamivir, and laninamivir for pharmacists working in healthcare institutionsCitation22. In addition, a certain percentage of pharmacists may allow patients to inhale drugs during their guidance. It is reported that some pharmacists performed guidance and demonstration on inhalation technique, as well as let the patients inhale the drugs on the spot—the percentage of pharmacists who let them inhale was 52.6% for hospital pharmacists and 16.1% for those working in external dispensing pharmacies—in patient education for asthma inhalation therapyCitation23. They might do it for anti-influenza therapy as well.

Even though no noteworthy difference in time was found by their own occupation in physicians and pharmacists among the types of facilities, some differences were observed over time in the entire workplace. Hospitals took a longer time than clinics among the physicians’ workplaces and pharmacies among pharmacists’ workplaces. It took longer in hospitals, probably because the physicians, pharmacists, nurses, and other occupations contributed to it. A higher percentage of internal prescriptions in hospitals than in clinics in this study may be consistent with the long time in hospitals. Moreover, an expert suggested that shorter time in clinics, for not only the entire workplace but also physicians themselves, maybe because the clinics have more regular patients than hospitals.

Regarding the monetary value of fear of infection when guiding and/or supporting administration, remarkable differences were seen among the types of questions. It may be impractical to assess the validity of the data by comparing it with past research data. Furthermore, determining which type of question is appropriate may be quite difficult. However, even though the amounts were different among questions, a similar tendency was observed among the types of occupations and between administration routes in all types of questions. Consequently, the difference in the values could be evaluated using the questions in this study.

A larger amount was evident in the value type questions (asking to evaluate the value of fear) compared with the WTP type questions (asking about the amount of willingness to pay). In particular, a lower WTP for being replaced by another person (Type C question) might be consistent with the fact that people tend to estimate a higher value on their work than others do. Willingness to accept—minimum compensation a person would require to abandon a service—is reportedly higher than WTPCitation24–26, although the value should be similar for the two approaches. Moreover, it might be reasonable from the “prospect theory” in the context of behavioral economics that people prefer to avoid loss rather than gain, if it is considered that the value of fear is positive as it is based on an evaluation of the respondents themselves, while WTP is negative as it is paid by the respondents to othersCitation27.

The two-step method questions, which ask about the value of fear after the total value of guidance and/or support, including fear, showed a lower value for fear than the direct method. Although the value from the two-step method (Type D question) might be underestimated, it may be a more realistic value than the direct method’s value. The lower value in the two-step method may be explained by the “framing effect” in the context of behavioral economicsCitation27. This question itself did not set the frame of the amount of the value, but the respondents set a frame of the amount of the value for guidance and/or support by answering the question, which can be considered to induce a lower value of fear compared to the questions without the previous questions. If it is true, the value might be underestimated. However, there might be a possibility that estimating the monetary value of the disappearance of fear in the direct method in the value type question (Type B question) was difficult for the respondents because the respondents needed to imagine a virtual situation. In comparison, the value in the two-step method could be based on their own experience, producing a more realistic value.

To calculate the cost of fear, we selected the value obtained from the answer to the Type D question. This is because the answer from the value evaluation type question is prioritized as predetermined (described in the Methods section), and the monetary value answered to the two-step method question is conservative and might be more realistic than that from the direct method. We calculated the corresponding monetary value for infection obtained from the Type D question based on purchasing power paritiesCitation28 to some countries as reference (). In interpreting the cost of fear, vaccination might have an impact on the fear of infection and its cost. Based on a high vaccination rate for influenza, which was reportedly 87.3% for healthcare workers in 2010–2011Citation29, we assume the cost of fear in this survey is mostly from vaccinated respondents. Additionally, it is notable that we conducted this survey during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, due to the pandemic’s overall effect, the costs may have been overestimated.

Table 11. Corresponding monetary value for fear of infection based on purchasing power parities.

The monetary value of fear was the lowest among pharmacists and the highest among certified care workers. According to experts’ opinions, pharmacists might consider that they could be cured after taking medicine if they were infected. Thus, the values of fear were not large for this group, although they felt fear of the risk of infection. In contrast, certified care workers have less knowledge about infectious diseases than other occupations because of the characteristics of their jobs, which was also indicated in a previous reportCitation18. Another possibility is that certified care workers probably contact patients more frequently than those in other occupations. Therefore, they might think that they are at a higher risk of infection. In fact, to prevent infections for care workers in various situations, such as eating assistance, excretion assistance, and medical procedures, a guidebook of infectious disease control measures in long-term care facilities for the elderly has been proposedCitation30. Consequently, they might always be aware of the possibility of becoming infected while working, resulting in an estimation of a higher value for fear. In addition, they are with elderly people who are more affected by infectious diseases, which might influence their feelings of fear.

When comparing the value of fear between administration routes, a much higher value was found for inhalants than oral drugs among pharmacists, as compared to those in other occupations. A longer guidance time required for inhalants than for oral antivirals might increase the risk of infection. Moreover, as mentioned earlier, a certain percentage of pharmacists reportedly allow patients to inhale drugs during guidance. While inhaling drugs, it is a matter of concern if patients cough violently and spray droplets. In fact, some Japanese pharmacist associations have recently submitted requests that prescribing inhalant drugs should be avoided because of concerns about infection from patients if they are co-infected with influenza and COVID-19Citation3,Citation31. In contrast, fewer differences between routes were observed in certified care workers. This might be because they have less knowledge and information about inhalants, which is caused by less experience of using them as compared to physicians and pharmacists. Certified care workers who had experience regarding guidance and/or support for antiviral drug administration were 64% for oral drugs and 35% for inhalants. Fewer experiences with inhalants are consistent with a survey in 2016 that targeted physicians who supervised care facilities for the elderly. The percentage of drugs that could be handled in their facilities was 96.6% for oral and 26.3% for inhalantsCitation32.

A previous study found that baloxavir (a single dose oral antiviral) had the lowest cost based on drug cost and intangible costs for patients, among available brand and generic anti-influenza drugsCitation4. After incorporating the costs for HCPs, baloxavir remained the lowest-cost treatment ().

This study has several limitations. First, this study was conducted through an online survey of individuals willing to participate in online surveys in advance. Although we gathered respondents with a wide variety of attributes, they were not necessarily representative of Japanese society. As described in the second paragraph of the Discussion section, we confirmed the external validity of this study by comparing it with nationwide statistics. Second, the reliability of the results depends on whether the respondents accurately understood the questions and the extent of their truthfulness. Moreover, Yasunaga et al. described that when evaluating healthcare services using the contingent valuation method, accurate evaluation of economic value cannot be expected if the virtual scenario includes insufficient informationCitation5. In this study, the difference in experience between respondents may reflect the difference between answers, because the study required respondents to evaluate the monetary value based on actual experiences, rather than virtual scenarios. Notably, while a price included in a virtual scenario often affects the value of an answer, our study did not include a certain price, which may contribute to avoiding this type of bias. However, the questions regarding WTP for replacing the work with another person (Type C) or value of guidance and/or support for antiviral drug administration with fear (Type D) may possibly make the respondents imagine medical remuneration points for related work, such as medication history management and guidance fees for pharmacists. Third, we should consider the possibility of respondents having lapses in memory or the effect of recall bias on the questions asking about their experiences. Fourth, this study targeted physicians, pharmacists, and certified care workers as HCPs involved in the guidance and/or support for antiviral drug administration. However, other HCPs may have also been involved. Although we applied the required time in the entire workplace to include them, the time spent by other occupations might not have been accurately estimated, and the cost of fear among people engaged in other occupations was not included. In addition, the time might have been double-counted, in which two or three of the respondents’ occupations conducted guidance and/or support if summing them up. Finally, in the discussion, we compared the costs between available antivirals by adding intangible costs for patients in the previous study, which was also based on an online survey. Consequently, similar to this study, the limitations associated with the previous survey study should be considered. Moreover, while only patients aged 20–64 years were included in the previous study, this study did not restrict the age of patients whom HCPs guide and/or support for antiviral drug administration. Thus, the age distribution of patients in this study might be similar nationwide, causing a disagreement with the patients’ characteristics of the previous study.

Conclusions

The cost of guidance and/or support for antiviral drug administration was estimated based on a survey of physicians, pharmacists, and certified care workers. The results suggest that inhalant antivirals require a longer time for guidance and/or support and have a higher value for fear of infection compared with oral antivirals among physicians and pharmacists. For certified care workers, the required time for guidance and/or support in their entire workplace was longer, and the cost of fear was estimated to be higher than those in other occupations. However, almost no difference was observed between the two administration routes. Therefore, the difference in costs between administration routes was observed exclusively by physicians and pharmacists. When calculating the total cost per treatment, by adding drug cost and costs of convenience for patients and productivity loss reported in a previous study, to the costs for HCPs obtained in this study for each available antiviral (oral or inhalant) in Japan, a single-dose oral antiviral, baloxavir, was suggested to have a lower cost than others. We believe that the information provided in this study will be useful for the treatment choice for influenza.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was supported by Shionogi & Co., Ltd.

Declaration of financial/other interests

KK, HI, and SH are employees of Shionogi & Co., Ltd. KK, HI, and SH report company stock in Shionogi & Co., Ltd. KI and TT are employees of Milliman Inc., which has received research grants from Shionogi & Co., Ltd. MA received consulting fees from Shionogi & Co., Ltd. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

KK, HI, SH, and MA contributed to the study conception. All authors contributed to the study design and data interpretation. Data analysis was performed by KI. The first draft of the manuscript was written by TT, and all authors commented on the previous versions of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.1 MB)Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the following experts in each occupation for valuable discussions on interpreting the results: Dr. Nobuo Hirotsu (Hirotsu Clinic), Ms. Yuki Sakuma (Department of Social Welfare, Niigata University of Health and Welfare), Dr. Daisuke Tamura (Department of Pediatrics, Jichi Medical University), and Dr. Yasuhiro Tsuji (School of Pharmacy, Nihon University). We thank INTAGE Healthcare Inc., and M3. Inc. for the execution of the online survey and Editage for English language editing.

References

- [About influenza in this winter (2019/2020 season)] [Internet]. Tokyo (Japan): National Institute of Infectious Diseases; 2020. [cited 2021 July 5]; Available from: https://www.niid.go.jp/niid/images/idsc/disease/influ/fludoco1920.pdf

- [Recommendations by the Japanese Association for Infectious Diseases: In preparation for influenza and COVID-19 in this winter] [Internet]. Tokyo (Japan): The Japanese Association for Infectious Diseases; 2020. [cited 2021 July 5]; Available from: https://www.kansensho.or.jp/uploads/files/guidelines/2012_teigen_influenza_covid19.pdf

- [Guide to treatment and prevention of influenza in 2020/21 season—For the prevalent season of influenza in 2021/21] [Internet]. Tokyo (Japan): Japan Pediatric Society; 2020. [cited 2021 July 5]; Available from: http://www.jpeds.or.jp/uploads/files/2020-2021_influenza_all202012.pdf

- Hosogaya N, Takazono T, Yokomasu A, et al. Estimation of the value of convenience in taking influenza antivirals in Japanese adult patients between baloxavir marboxil and neuraminidase inhibitors using a conjoint analysis. J Med Econ. 2021;24(1):244–254.

- Yasunaga H, Ide H, Imamura T, et al. Contingent valuation for health care services. Review of domestic studies and outline of foreign investigations. Jpn J Public Health. 2006;53(11):818–830.

- Mitchell RC, Carson RT. Using surveys to value public goods: the contingent valuation method. Washington DC: RFF Press; 1989.

- Carson RT, Mitchell RC, Hanemann M, et al. Contingent valuation and lost passive use: damages from the exxon Valdez oil spill. Environ Resour Econ. 2003;25(3):257–286.

- Hanley N, Ryan M, Wright R. Estimating the monetary value of health care: lessons from environmental economics. Health Econ. 2003;12(1):3–16.

- Smith RD. Construction of the contingent valuation market in health care: a critical assessment. Health Econ. 2003;12(8):609–628.

- [Japanese Basic Survey on Wage Structure on 2018. [Internet]. Tokyo (Japan): Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; 2019. [cited 2021 July 5]; Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/itiran/roudou/chingin/kouzou/z2018/dl/01.pdf

- [Handbook of Labour Statistics] [Internet]. Tokyo (Japan): Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; 2018. [cited 2021 July 5]; Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/youran/index-roudou.html

- [National health insurance drug price list 2020 August (oral)] [Internet]. Tokyo (Japan): Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; 2020. [cited 2020 Nov 26]; Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/topics/2020/04/dl/tp20200826-01_01.pdf

- [National health insurance drug price list 2020 August (topical agent)] [Internet]. Tokyo (Japan): Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; 2020. [cited 2020 Nov 26]; Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/topics/2020/04/dl/tp20200826-01_03.pdf

- [Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects] [Internet]. Tokyo (Japan): Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology and the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. 2014. Partial revision in 2017. [cited 2021 July 5]; Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-10600000-Daijinkanboukouseikagakuka/0000153339.pdf

- [Statistics of physicians, dentists, and pharmacists 2018] [Internet]. Tokyo (Japan): Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; 2019. [cited 2020 Nov 26]; Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/ishi/18/index.html

- [Long-term care service facilities and offices survey 2018] [Internet]. Tokyo (Japan): Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; 2020. [cited 2020 Nov 26]; Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/kaigo/service18/index.html

- [Interpretation of Article 17 of the Medical Practitioners' Act, Article 17 of the Dentists Act, and Article 31 of the Act on Public Health Nurses, Midwives and Nurses (Notification)] [Internet]. Tokyo (Japan): Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; 2005. [cited 2021 July 5]; Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/web/t_doc?dataId=00tb2895&dataType=1&pageNo=1

- Park H, Miki A, Satoh H, et al. An approach for safe medication assistance in nursing homes: a workshop to identify problems of and plan measures for care workers. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2016;136(6):913–923.

- Tagashira Y. [Medication management and administration assistance]. Itsudemo Genki No. 314 [Internet]. 2017. Dec. [cited 2021 July 5]; Available from: https://www.min-iren.gr.jp/?p=33413

- Fujimura S. [Infection prevention of influenza virus and proper use of anti-influenza drugs in pharmacies]. Med Drug J. 2018;54(10):2255–2260

- Kashiwagi S, Yoshida S, Yamaguchi H, et al. Clinical efficacy of long-acting neuraminidase inhibitor laninamivir octanoate hydrate in postmarketing surveillance. J Infect Chemother. 2013;19(2):223–232.

- Sunagawa S, Higa F, Kamimura T, et al. A change in the sales amounts of anti-influenza drugs in Okinawa and the survey by questionnaire about the factor. Jpn J Chemother. 2011;59(5):486–494.

- Yokota T, Adachi Y, Onoue Y, et al. Patient edication for asthma inhalation therapy by pharmacists: differences between hospital and community pharmacies. JJACI. 2001;15(2):208–214.

- Grutters JP, Kessels AG, Dirksen CD, et al. Willingness to accept versus willingness to pay in a discrete choice experiment. Value Health. 2008;11(7):1110–1119.

- Hammitt JK. Implications of the WTP-WTA disparity for benefit-cost analysis. J Benefit Cost Anal. 2015;6(1):207–216.

- Martín-Fernández J, del Cura-González MI, Gómez-Gascón T, et al. Differences between willingness to pay and willingness to accept for visits by a family physician: a contingent valuation study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:236–236.

- Tversky A, Kahneman D. Advances in prospect theory: cumulative representation of uncertainty. J Risk Uncertainty. 1992;5(4):297–323.

- OECD Data: Purchasing power parities (PPP) [Internet]. Paris (France): Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. [cited 2021. November 2]; Available from: https://data.oecd.org/conversion/purchasing-power-parities-ppp.htm.

- To KW, Lai A, Lee KC, et al. Increasing the coverage of influenza vaccination in healthcare workers: review of challenges and solutions. J Hosp Infect. 2016;94(2):133–142.

- [Infection control manual in welfare facility for elderly: Revised edition] [Internet]. Tokyo (Japan): Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; 2019. [cited 2021 July 5]; Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/000500646.pdf

- [Movement to avoid influenza antiviral inhalant—Fear of spread of coronavirus through coughing]. Nihon Keizai Shinbun [Internet]. 2020. Sept 7 [cited 2021 July 5]; Available from: https://www.nikkei.com/article/DGXMZO63525750X00C20A9000000/

- [Study on the appropriate countermeasures to infectious diseases, including caused by multidrug-resistant bacteria, at nursing facilities] [Internet]. Tokyo (Japan): Japan Association of Geriatric Health Services Facilities; 2017. [cited 2021 July 5]; Available from: https://www.roken.or.jp/wp/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/H28_kansensyo_report.pdf