Abstract

Objectives

Systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (sALCL) is a rare hematological malignancy with poor prognosis, which is associated with a significant economic burden. This study aimed to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of brentuximab vedotin (BV) in comparison to conventional chemotherapy in patients with relapsed/refractory sALCL, from a Chinese healthcare perspective.

Methods

A partitioned survival model with three health states (progression-free survival, post-progression survival, and death) was adapted to compare BV against chemotherapy. Comparator represented a basket of commonly used chemotherapies in China. Two cohorts in each arm were estimated, representing patients receiving no transplant and autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) after BV or chemotherapy. Clinical data was obtained from the pivotal phase-II trial (NCT00866047) for BV and also from the literature for a comparator. Resource use items covered drug acquisition and administration; concomitant medications; ASCT; treatment of adverse events; and long-term follow-up. Cost parameters were based on Chinese sources. Outcomes were measured in quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). Both costs and effects were discounted at 5% according to Chinese guidelines. The impact of uncertainty was evaluated using deterministic and probabilistic sensitivity analyses.

Results

The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for BV vs. chemotherapy was $9,610 (¥62,084) per QALY in the base case. The main model driver was superior progression-free and overall survival benefits of BV. The ICERs were relatively robust in the majority of sensitivity analyses, ranging around ±10% of the base case. Under the conventional decision thresholds (1–3 times of Chinese per capita GDP), the probability of BV being cost-effective ranged from 56 to 100%. Limitations of the study included the lack of comparative data from the trial and the small and heterogeneous sample due to its disease nature.

Conclusions

BV may be a cost-effective treatment vs. chemotherapy in treating relapsed or refractory systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma in China.

Introduction

Systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (sALCL) is an aggressive subtype of T-cell lymphoma characterized by the strong and uniform expression of CD30Citation1. It is a rare blood malignancy. In China, the annual incidence rate is estimated as 0.13 per 100,000 personsCitation2, which is lower than in western countriesCitation3. The mortality rate associated with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (covering T-cell subtype) in China is reported to be higher than that in the westCitation2. sALCL is also associated with a substantial reduction in patients’ health-related quality of lifeCitation4.

sALCL is a potentially curable malignancy with appropriate treatment. However, ∼40–65% of patients relapseCitation5. No specific guideline for relapsed or refractory sALCL (RRsALCL) is available in China. Nevertheless, the common treatment for RRsALCL is salvage chemotherapy, with some patients receiving adjuvant radiotherapy. A proportion of patients with an adequate response after chemotherapy receive autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT). However, the overall outcome is unsatisfactory with a 5-year progression-free survival (PFS) rate of up to 56%Citation6,Citation7. In addition, the rate of patients receiving ASCT is relatively lower in China than in western countries due to high procedure costs and affordability issues as indicated by clinical expertsCitation8.

Brentuximab vedotin is an antibody-drug conjugate that targets CD30-expressing malignant cells by binding CD30 on the surface. Targeted delivery of monomethyl auristatin E, the microtubule-disrupting agent, to CD30-expressing tumor cells is the primary mechanism of actionCitation9,Citation10. A single-arm, open-label, multicenter, phase II trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of brentuximab vedotin in 58 patients with RRsALCL demonstrated an overall response rate of 86% with 66% of patients achieving a complete response (CR), a median of progression-free survival of 13 months, and a median overall survival not being reached (a median observation time of 33.4 months)Citation11. Based on this evidence, brentuximab vedotin has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for the treatment of patients with sALCL after the failure of at least one prior multiagent chemotherapy regimen and is since then recommended in several treatments guidelinesCitation12–14. Furthermore, the 5-year follow-up of the original trial was published in 2017 to provide the long-term outcomes of brentuximab vedotinCitation1. In China, the market authorization of brentuximab vedotin for recommendation on the treatment of RRsALCL, as well as relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma, was granted by the National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) in May 2020.

The present study aimed to assess the cost-effectiveness of brentuximab vedotin for treating relapsed or refractory systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma from a Chinese healthcare perspective.

Patients and methods

Expert’s survey

sALCL is a rare disease in China and no specific guideline exists for treating RRsALCL. Consequently, it was decided to conduct a face-to-face survey of clinical experts to understand the treatment pattern and healthcare utilization of RRsALCL. To be eligible, clinical experts had to be working in a tertiary hospital (where the majority of lymphoma patients are treated in China) and providing treatments for individual patients. A total of five clinical experts were selected, one each from Shanghai, Tianjin, Harbin, Nanjing, and Guangzhou. This was done to take into account the different geographic areas, economic development, and the number of lymphoma cases treated in China. The input provided by these experts, i.e. treatment pathway, resource uses, and estimated prices for treatment were used to populate the model and is noted as sourced from “expert’s survey”.

Population

In line with the Chinese marketing authorization, the economic model assessed brentuximab vedotin in treating RRsALCL in adult patients.

Comparators

Interviews with local clinicians (expert’s survey)Citation8 and a targeted review suggested the following chemotherapies were most commonly used in RRsALCL:

ICE (ifosfamide, carboplatin and etoposide)

DHAP (dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, and cisplatin)

GDP (gemcitabine, dexamethasone and cisplatin)

Gem-Ox (gemcitabine and oxaliplantin)

Thus, combined chemotherapy consisting of these 4 regimens (weighed by their proportions), was used as an appropriate comparator of brentuximab vedotin in the model.

Model structure

A partitioned survival model in Microsoft Excel 2010 was used, adapted from the model used in the NICE Technology appraisal guidance [TA478]: Brentuximab vedotin (as monotherapy) for treating relapsed or refractory systemic anaplastic large cell lymphomaCitation13. The model assumed three health states including progression-free survival (PFS), post-progression survival (PPS), and death. The proportion of patients in the PFS and death state over time was estimated directly from the PFS and OS curves, respectively; the proportion of patients in the PPS state was estimated as the difference between the OS curve and the PFS curve. According to the proportion of patients in the PFS and PPS states over time, the associated costs and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) were estimated.

To reflect the Chinese local treatment pathway (based on the expert’s survey)Citation8, costs and health effects for four cohorts were estimated in the model:

Brentuximab vedotin arm:

Cohort 1. Patients who received only brentuximab vedotin (brentuximab vedotin, no SCT [stem cell transplant])

Cohort 2. Patients who received brentuximab vedotin followed by ASCT (brentuximab vedotin + ASCT)

Chemotherapy arm:

Cohort 3. Patients who received only chemotherapy (chemotherapy, no SCT)

Cohort 4. Patients who received chemotherapy followed by ASCT (chemotherapy + ASCT)

Following the advice from the local experts, allogenic stem cell transplant (alloSCT) was not included in the current model. The experts explained that the use of alloSCT in China was extremely limited due to its high costs, scarcity of donors and hospital capacity. In order to estimate costs and QALYs for brentuximab vedotin arm, costs and health effects for cohorts 1 and 2 above were weighted according to the proportion of patients in each cohort (described in detail below). Costs and QALYs for the chemotherapy arm were estimated using the same approach for cohorts 3 and 4. Additionally, the model adopted a Chinese healthcare perspective with a life-time horizon (60 years). The price reference year was 2020, and the discount rate for both costs and health outcomes was 5%Citation15.

Model inputs

Clinical data

The main clinical data of brentuximab vedotin was sourced from the 5-year follow-up data of the pivotal SG035-0004 trial (NCT00866047)Citation1. Briefly, SG035-0004 trial was a single-arm phase II study evaluating the efficacy and safety of brentuximab vedotin in 58 patients with RRsALCL. In its long-term follow-up analysis, with a median observation of 6 years, it was reported that patients who achieved complete response had 79% OS and 57% PFS at 5 years of the follow-up period, with median OS/PFS, not reachedCitation1. In the current model, PFS and OS data for brentuximab vedotin (no SCT) were based on the subset of 41 patients in the trial who did not receive SCT. Furthermore, SG035-0004 was a single-arm trial that precluded the availability of comparator information. Thus, a self-control comparison approach was adopted to provide the clinical data for the chemotherapy (no SCT) cohort. The subgroup of 39 patients in SG035-0004 whose most recent therapy was for the relapsed or refractory disease were used to extract the PFS from the most recent cancer-related therapy before brentuximab vedotin. It was not feasible to collect OS from a self-comparison, therefore, OS data for the chemotherapy (no SCT) cohort was sourced from the literatureCitation6. The OS and PFS for patients receiving ASCT were also based on the literatureCitation5. Hence, brentuximab vedotin + ASCT and chemotherapy + ASCT cohorts shared the same OS and PFS curves.

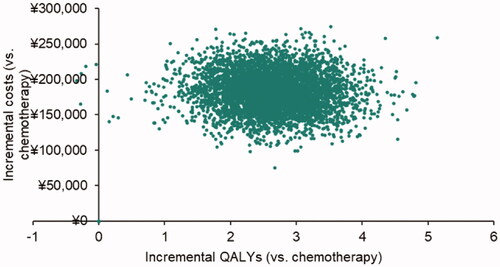

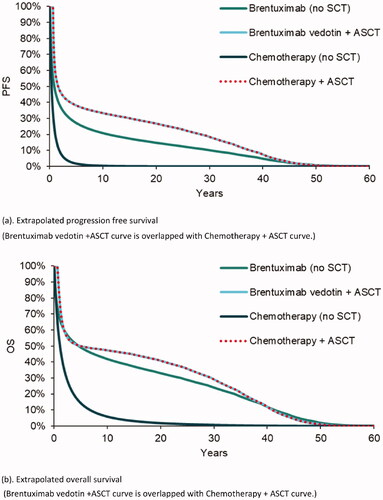

For long-term progression, each curve was modeled using parametric survival methods and the best-fit model was selected for the base case. Specifically, the PFS and OS of brentuximab vedotin (no SCT) cohort used a standard model with Gamma distribution; curves of chemotherapy (no SCT) cohort were based on a lognormal distribution. Mixture cure modelCitation16 was applied for curves of cohorts with ASCT as the data showed a plateau at ∼3 years, suggesting a cure fractionCitation5. The extrapolated PFS and OS curves applied in the model are presented in . Alternative curve fitting models can be found in Appendix 2.

Figure 1. Progression free survivor and overall survival, by cohort. (a) Extrapolated progression free survival (Brentuximab vedotin + ASCT curve is overlapped with Chemotherapy + ASCT curve). (b) Extrapolated overall survival (Brentuximab vedotin + ASCT curve is overlapped with Chemotherapy + ASCT curve).

The proportion of patients in cohort 2 and cohort 4 (brentuximab + ASCT and chemotherapy + ASCT, respectively) was estimated by multiplying the proportion of eligible patients (i.e. patients who achieved complete response [CR] or partial response [PR]) in each brentuximab vedotin and chemotherapy (no SCT) cohorts with the ratio of eligible patients who ultimately received ASCT (assumed as 30% for both cohorts based on the expert’s survey). With the response rate (CR + PR) of brentuximab vedotin sourced from the SG035-0004 trial and with the response rate of chemotherapy based on the self-control group, the proportion of patients in cohort 2 and cohort 4, in the base case, was estimated at 25.8 and 13.1%, respectively.

Resource utilization and costs

Resource use included drug acquisition and administration, concomitant medications, radiotherapy, ASCT, treatment of adverse events (AEs), and long-term follow-up.

The cost of brentuximab vedotin was $2,891 US dollars (¥18,680 RMB) per vial (50 ml). Based on an average patient weight of 60 kg, it was calculated two vials per person per treatment cycle. Therefore, the brentuximab vedotin cost per cycle was $5,783 (¥37,360) per patient. The average treatment duration was seven cycles for the patient who received brentuximab vedotin only, whilst the average number was three for patients who received ASCT after brentuximab vedotin treatmentCitation11. In terms of chemotherapy, standard dose information for the selected chemotherapy regimens was taken from the literatureCitation17–20. Cycles of chemotherapy were estimated based on clinical expert opinion (six cycles for chemotherapy only and four for patients with ASCT after chemotherapy). Drug prices were taken from Chinese open-source Yaozh (药智网)Citation21 and PricentricCitation22. The cost of each regimen is presented in . The proportion of patients was assumed 25% for each regimen (expert’s survey).

Table 1. Cost inputs.

The concomitant medications-antiemetics for all chemotherapies and brentuximab vedotin treatment and antifungal, antiviral, and antibacterial agents for GDP and Gem-Ox were captured in the model, following the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelinesCitation23,Citation24 and confirmed by local experts.

Based on the expert’s surveyCitation8, 20% of patients were assumed to potentially require radiotherapy as an adjunction to their chemotherapy, whose cost was estimated as $4,644 (¥30,000). Due to the complex resource utilization of SCT, especially the complicated multiple costing items related to SCT, experts were asked to give an estimation of the bulk cost of conducting one ASCT, which was estimated as $30,958 (¥200,000). This total cost of ASCT included the cost of acute adverse events or complications (excluding long-term follow-up).

The frequency and resource utilization of follow-up visits/tests/scans were stratified by whether patients were under treatment or not. No difference between with or without ASCT was assumed as the specific costs associated with ASCT were already included in the unit cost of ASCT. Patients who entered the “post-progression” state were assumed to receive one post-progression therapy, based on the expert’s survey. The long-term follow-up cost for post-progression patients was assumed to be equal to the cost for the on-treatment period.

The cost of treating adverse events, including all grade 1–2 events occurring in ≥10% of patients and grade 3–4 events occurring in ≥5% of patients, were calculated. The cost associated with each AE can be found in Appendix 1, based on local unit costCitation25.

Utility

Given the limited availability of utility data in China, the utility input was based on the same sources as those in TA478Citation13. The model assumed that the base case was with a 5% decrement for long-term survivors compared to the age-adjusted population normCitation26. Thus, the impact of the disease was modeled as a decrement subtracted from the age-adjusted population norm with a 5% decrement. For no ASCT cohorts, utilities for a patient with different response categories were sourced from the study by Swinburn et al.Citation4, as shown in . For the ASCT cohort, based on expert opinions, a distinction was made between post-ASCT stages, including time from ASCT to 6 months and from 6 months to cure, as shown in . Similar to ASCT cohorts, the utility for patients who were cured was assumed to be the same as that of long-term survivors.

Table 2. Utility inputs.

The impact of adverse events on quality of life was incorporated by applying a QALY decrement for each event. The expected QALY decrement associated with each AE was determined by the combination of the utility decrement for the event, the duration of the event, and the proportion of patients experiencing the event. These AE decrements and durations were assumed to be the same as those used in the TA478.

Sensitivity analysis

A wide range of deterministic sensitivity analyses was conducted to test the robustness of the model results. For instance, to explore the impact of self-control comparison, the base case PFS/OS data of chemotherapy was increased and decreased by 25%, respectively, in each sensitivity analysis, as well as using alternative data sources. Assumptions based on expert opinion were also investigated, such as the proportion of patients receiving ASCT in each arm and the composition of chemotherapy (as most expensive and cheapest). Others included various parameter curve fitting models for all OS/PFS data, different discounting rates, and alternative utility scores for health states, with vs. without disutilities of AE. More details can be found in Appendix 2.

Probabilistic sensitivity analysis, based on 5000 Monte Carlo simulations, was also conducted to estimate the uncertainty associated with cost and health outcome measures. Conventionally, the range of cost-effectiveness thresholds was as one, double, and triple value of Chinese per capita gross domestic product (GDP, 2020Citation27).

Results

Long term clinical outcomes

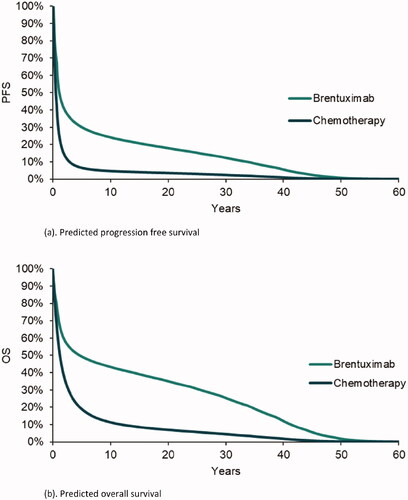

The PFS and OS curves of brentuximab vedotin vs. chemotherapy predicted by the model are presented in . Brentuximab vedotin had superior PFS and OS curves than the comparator. In terms of mean time-in-state, brentuximab vedotin was associated with an average of 8.30 and 14.89 years for PFS and OS, respectively (2.17 and 4.54 years for chemotherapy comparator). This was primarily driven by the higher PFS and OS curves for brentuximab vedotin (no SCT) compared to chemotherapy (no SCT). For example, the median OS was 4.64 years for brentuximab vedotin (no SCT) and 1.11 years for chemotherapy (no SCT).

Figure 2. Predicted progression free survivor and overall survival, by comparator. (a) Predicted progression free survival. (b) Predicted overall survival.

QALYs and LYs

Disaggregated QALYs are presented for each comparator in , as well as life-years (LYs). As shown in the table, brentuximab vedotin yielded incremental QALYs of 2.90 vs. chemotherapy; this was driven by superior PFS and OS curves of brentuximab vedotin.

Table 3. Discounted QALYs and LYs, by comparator.

Costs

Disaggregated costs by resource category are presented for brentuximab vedotin vs. chemotherapy in . Brentuximab vedotin yielded an incremental cost of $27,859 (¥179,979) vs. chemotherapy. This was driven by the cost of drug acquisition, offsetting the savings from administration, AEs, follow-up care costs. The incremental cost of ASCT was also positive as a result of a greater proportion of patients who proceeded to ASCT following brentuximab vedotin compared to chemotherapy.

Table 4. Discounted costs by resource category, by comparator.

ICER

In the base case, the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for brentuximab vedotin was $9,610 (¥62,084) per QALY vs. chemotherapy.

Sensitivity analysis

The results of deterministic sensitivity analysis suggested the robustness of the base case. Most ICERs in the investigated scenarios ranged around ±10% of the base-case ICER and were under the Chinese threshold of 1 × GDP ($11,214/QALY [¥72,447/QALY]), see Appendix 2. The only exceptions were the cases that applied 3 and 8% of discounting rates (−21 and +34%). This was due to the fact that whilst health outcomes were spread over a period of a lifetime, which was sensitive to the discounting rate, the majority of costs were accrued in the first year of the treatment and not affected by discounting. All other investigated scenarios, such as an alternative to self-control comparison, proportion of ASCT, chemotherapy composition and parameter curve fitting had limited impact on ICERs.

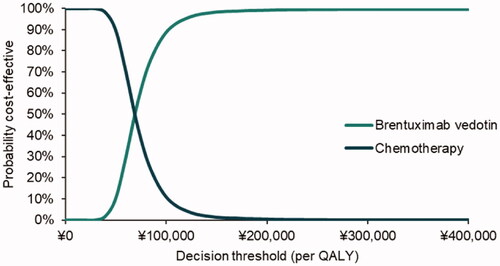

The cost-effectiveness scatters plot and acceptability curve (CEAC) are presented in , respectively. Under the conventional decision thresholds (1, 2, and 3 × Chinese per capita GDP in 2020, namely $11,214/QALY [¥72,447/QALY], $22,427/QALY [¥144,894/QALY] and $33,641/QALY [¥217,341/QALY]), the probability of brentuximab vedotin vs. chemotherapy being cost-effective was 56, 98, and 100%.

Discussion

This study assessed the cost-effectiveness of brentuximab vedotin monotherapy vs. chemotherapy in treating Chinese patients with RRsALCL. The base case analysis yielded an incremental 2.90 QALYs under an incremental cost of $27,859 (¥179,979), which resulted in an ICER of $9,610 (¥62,084) per QALY gained. A variety of deterministic sensitivity analyses were conducted to explore uncertainty relating to all aspects of model assumptions, such as self-control comparison and clinical expert opinions. The majority of analyses yielded ICERs below the threshold of $11,214 (1xGDP, ¥72,447). Therefore, the model results could be considered robust. The probability that brentuximab vedotin is cost-effective at the 1× GDP ICER threshold was 56%.

In the case of rare diseases, medicines for treatment are usually expensive, and as a result, patients’ access to those drugs is often restricted. In contrary, brentuximab vedotin has demonstrated its cost-effectiveness for treating RRsALCL compared to standard treatment, for instance, in the UK NHS settingCitation13, where it was consequently accepted by the NHS and benefited their patients. Other studies also report the cost-effectiveness of brentuximab vedotin in RRsALCLCitation28,Citation29. Similarly, in the current study, brentuximab vedotin demonstrated its cost-effectiveness compared to chemotherapy-based therapy in a Chinese setting, with an extensive sensitivity analysis to support the robustness of its results. Such evidence can be used to support the future National Reimbursed Drug List (NRDL) listing in China and ensure that the need of local patients can be met. Furthermore, the unit price of brentuximab vedotin was reduced to $2,418 (¥15,620) while this manuscript was undergoing peer-review. Lower ICER would be expected if the price of brentuximab vedotin drops in China in the future.

The current study faced several challenges. For instance, given that the local clinical data was scarce, the data from the global SG035-0004 trial was used to inform the efficacy and safety of brentuximab vedotin for the current Chinese model adaptation. A local trial C25010, investigating the efficacy and safety of brentuximab vedotin in Chinese patients with RRsALCL, was identified (NCT02939014)Citation30. However, due to its small sample size (n = 9) and immature survival curves (short follow-up <18 months), it was not recommendable to use such data for populating the economic models. To investigate the potential difference in clinical outcome, the Chinese trial and SG035-0004 were compared in terms of patient baseline characteristics. For example, it was observed that the median age of patients was 52 years in SG035-0004 and 44 in C25010, respectively. Furthermore, whilst in the SG035-0004 trial 26% of patients were with prior SCT and the median number of prior chemotherapies was 2, those numbers in the C25010 study were 44 and 1%, respectively. Nevertheless, the findings of SG035-0004 trial indicated that all the analyzed subgroups of patients achieved clinically meaningful antitumor activity, and no subgroup of patients was determined to be more likely to achieve CRCitation11. The results of its 5 years follow-up study also indicated that similar survival outcomes were observed between patients above 40 years old and below 40 years oldCitation1. It was, therefore, concluded by clinical experts that there was no expected difference between the two trials in terms of clinical outcomes. Thus, the use of SG035-0004 data to substitute the lack of proper Chinese data for the current adaptation was acceptable.

Given the SG035-0004 trial is a single-arm study, no comparator information was available. The PFS data of chemotherapy was sourced from SG035-0004 via a self-control comparison approach, which referred to participants’ prior chemotherapy before receiving brentuximab vedotin. There was also a lack of specific chemotherapy data in the literature for this group of patients. The uncertainty associated with this self-control approach could be either an over- or under-estimation of the outcome. More specifically, patients who experienced improvement with prior chemotherapies were unlikely to be included in the trial (underestimation); by definition, patients who experienced death from chemotherapies were not part of the trial (overestimation). However, the results of sensitivity analysis (increased and decreased 25% of hazard) suggested that this impact was limited. An alternative data source (the study by Mak et al.Citation6) was also explored and again the conclusion did not change.

Furthermore, the costing approach in the current model was mostly bottom-up-based. That is, identifying all relevant resource uses and assigning a unit price to each resource use, resulting in a total cost. It is known that, in comparison to the top-down approach, the bottom-up approach may represent a more precise estimate; however, the challenge of the bottom-up approach is to identify all used resourcesCitation31. It was likely that the average cost of chemotherapy applied in the model was underestimated as the estimated price for each chemotherapy was below the suggested costs by clinical experts interviewed in the survey. Thus, taking potentially underestimated costs associated with chemotherapy into account, the true ICER could have been even lower.

Several key assumptions underpinning the current study were sourced from expert’s opinions. Since this input is subjective, it encompasses a degree of uncertainty. Therefore, several sensitivity analyses were conducted to explore those assumptions and the results suggested a relatively limited impact. For instance, the proportion of patients receiving stem cell transplants after CR/PR from brentuximab vedotin or chemotherapy treatment. In the base case, it was assumed that the proportion for the brentuximab vedotin arm was the same as that in the chemotherapy arm (based on expert opinion). In the sensitivity analysis, a different source (the trial data) was used to inform the proportion and a lower rate for brentuximab vedotin was also tested. In both cases, the ICER only changed slightly. Furthermore, to explore the impact of not including alloSCT cohort on model structure, a separate model was built including cohorts of patients receiving alloSCT (10% of total SCT and $61,906 (¥400,000) for alloSCT) after brentuximab vedotin and chemotherapy treatment, respectively. The results suggested no change to the current conclusion (data available upon request).

It is known that ALK status is associated with disease progression and treatment choiceCitation32. As one of the current study’s limitations, the ALK status of the patients was not distinguished. However, in China ASCT is rarely conducted after the success of upfront therapy; ASCT is usually applied for relapsed/refractory patients. Furthermore, due to the small sample size, no statistical difference in OS/PFS outcomes was found between ALK + and − patients after using BV in the main efficacy data source (SG035-0004 trial). Another limitation in the current study is that alternative treatment, i.e. brentuximab vedotin with salvage chemotherapy (such as ICE), was not considered. Nevertheless, in China BV is approved as a single-use medication. The latest treatment guideline in China recommends BV as a single treatment (level II recommendation) or combined with PD-1 (level III)Citation33. Additionally, so far there is no trial data available for the efficacy of BV with salvage chemotherapy in relapsed/refractory patients. Thus, more research is needed to investigate the impact of the ALK status and alternative treatment.

Several other cost-effectiveness studies of brentuximab vedotin in different lines of treatment with various types of lymphoma have been investigatedCitation34–38. However, the results in some of these studies are conflicting with each other. For example, there are two studies investigating brentuximab vedotin with chemotherapy vs. chemotherapy in newly diagnosed stage III and IV Hodgkin lymphomaCitation37,Citation38. As the results of different efficacy data used and assumptions around the cost input, each study estimated a different incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). Furthermore, two studies investigating brentuximab vedotin as consolidation treatment following autologous stem cell transplant in Hodgkin lymphoma also reported conflicting resultsCitation35,Citation36. It is less clear about the main source of difference between the two studies as one study is reported as an abstract and provides limited details. Overall, it is therefore hard to judge whether one study is more valid than another and for this both personal bias as well as conflicting interestsCitation39 could play a role. Despite this, the availability of multiple studies conducted from different perspectives would allow decision-makers to compare evidence and make informed decisions.

Conclusion

In our base-case analysis brentuximab vedotin was associated with an ICER of $9,610/QALY (¥62,084/QALY) compared to chemotherapy. This health evaluation outcome remained stable in sensitivity analyses. Therefore, despite various assumptions adopted in the model, it was concluded that brentuximab vedotin may be a cost-effective treatment vs. chemotherapy in treating Chinese patients with relapsed or refractory systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This research was financially supported by Takeda (China) International Trading Co., Ltd.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

L.H.C. was employed by GongJing Healthcare and received funds from Takeda (China) International Trading Co., Ltd. to conduct the analysis. L.Z. is an employee of Takeda (China) International Trading Co., Ltd.

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Authors contributions

L.H.C. and L.Z. were responsible for the conception and design of the project. L.H.C. and J.L. were responsible for the analysis and development of the model. All authors participated in critically reviewing and interpreting the data. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content and all authors approved the final version for publication submission. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Han-I Wang, University of York, for her assistance in manuscript preparation.

References

- Pro B, Advani R, Brice P, et al. Five-year results of brentuximab vedotin in patients with relapsed or refractory systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Blood. 2017;130(25):2709–2717.

- The Global Cancer Observatory. China face sheet. Globanacan; 2020 [cited 2020 Oct 12]. Available from: http://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/160-china-fact-sheets.pdf

- Yang QP, Zhang WY, Yu JB, et al. Subtype distribution of lymphomas in southwest China: analysis of 6,382 cases using WHO classification in a single institution. Diagn Pathol. 2011;6(1):77.

- Swinburn P, Shingler S, Acaster S, et al. Health utilities in relation to treatment response and adverse events in relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma and systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56(6):1839–1845.

- Smith SM, Burns LJ, van Besien K, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation for systemic mature T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(25):3100–3109.

- Mak V, Hamm J, Chhanabhai M, et al. Survival of patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma after first relapse or progression: spectrum of disease and rare long-term survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(16):1970–1976.

- Fanin R, Ruiz De Elvira MC, Sperotto A, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation for T and null cell CD30-Positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma: analysis of 64 adult and paediatric cases reported to the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT). 1999;23:437–442.

- Takeda. RRcHL & RRsALCL expert’s survey; 2019.

- Senter PD, Sievers EL. The discovery and development of brentuximab vedotin for use in relapsed Hodgkin lymphoma and systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30(7):631–637.

- Francisco JA, Cerveny CG, Meyer DL, et al. cAC10-vcMMAE, an anti-CD30-monomethyl auristatin E conjugate with potent and selective antitumor activity. Blood. 2003;102(4):1458–1465.

- Pro B, Advani R, Brice P, et al. Brentuximab vedotin (SGN-35) in patients with relapsed or refractory systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma: results of a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(18):2190–2196.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN guidelines version 2.2015 peripheral T-cell lymphomas; 2015 [cited 2020 Jan 14]. Available from: https://www2.tri-kobe.org/nccn/guideline/hematologic/nhl/english/tcel.pdf

- NICE. Technology appraisal guidance [TA478]: brentuximab vedotin for treating relapsed or refractory systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma; 2017.

- d'Amore F, Gaulard P, Trümper L, et al. Peripheral T-cell lymphomas: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:v108–v115.

- Liu G, Hu S, Wu J, Wu J, Dong Z, Li H, eds. China guidelines for pharmacoeconomic evaluations. 2020th ed. Beijing: China Pharmaceutical Association; 2020.

- Lambert PC, Thompson JR, Weston CL, et al. Estimating and modeling the cure fraction in population-based cancer survival analysis. Biostatistics. 2007;8(3):576–594.

- Gutierrez A, Rodriguez J, Martinez-Serra J, et al. Gemcitabine and oxaliplatinum: an effective regimen in patients with refractory and relapsing Hodgkin lymphoma. Oncol Targets Ther. 2014;7:2097–2100.

- Velasquez WS, McLaughlin P, Tucker S, et al. ESHAP–an effective chemotherapy regimen in refractory and relapsing lymphoma: a 4-year follow-up study. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12(6):1169–1176.

- Dong M, He XH, Liu P, et al. Gemcitabine-based combination regimen in patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Med Oncol. 2013;30(1):351.

- Zelenetz AD, Hamlin P, Kewalramani T, et al. Ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide (ICE)-based second-line chemotherapy for the management of relapsed and refractory aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2003;14(Suppl 1):i5–i10.

- Yaozh website [cited 2020 Jan 14]. Available from: https://www.yaozh.com/

- Pricentric [cited 2020 Jan 14]. Available from: https://pricentric.alscg.com/alspc

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: prevention and treatment of cancer-related infections; 2016 [cited 2020 Jan 14]. Available from: https://jnccn.org/view/journals/jnccn/14/7/article-p882.xml?ArticleBodyColorStyles=Inline%20PDF

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: antiemesis; 2016 [cited 2020 Jan 14]. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/store/login/login.aspx?ReturnURL; https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/antiemesis.pdf

- Beijing Social Security Network [cited 2020 Jan 28]. Available from: https://m.chashebao.com/beijing/yiliao/17287.html

- Kind P, Hardman G, Macran S. UK population norms for EQ-5D; 1999.

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. China statistic yearbook 2020 [cited 2020 Jun 28]. Available from: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2020/indexch.htm

- Hux M, Zou D, Ma E, et al. A cost-effectiveness analysis of brentuximab vedotin in relapsed or refractory systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma. JHEOR. 2016;4(2):188–203.

- Zou D, Kendall R, Lin Q, et al. Cost-effectiveness of brentuximab vedotin in relapsed or refractory systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma in Taiwan. Value in Health. 2016;19(7):A811.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Brentuximab vedotin in Chinese participants with relapsed/refractory CD30-positive hodgkin lymphoma (HL) or systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma (sALCL) [cited 2021 Jun 17]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02939014

- Drummond M, O’Brien B, Stoddart G, et al. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 4th ed. New York: University Press; 1987.

- Ellin F, Landstr¨Om J, Jerkeman M, et al. Real-world data on prognostic factors and treatment in peripheral T-cell lymphomas: a study from the Swedish lymphoma registry. Blood. 2014;124(10):1570–1577.

- Guidelines of Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology. Guidelines of Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology: lymphoid malignancies 2021. Beijing: People’s Republic Publisher; 2014.

- Feldman T, Zou D, Rebeira M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of brentuximab vedotin with chemotherapy in treatment of CD30-expressing PTCL. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(2):e41–e49.

- Roth J, Carlson J, Ramsey S. Cost-Effectiveness assessment of brentuximab vedotin to prevent progression following autologous stem cell transplant in Hodgkin lymphoma in the United States. Blood. 2014;124(21):2657–2657.

- Hui L, von Keudell G, Wang R, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of consolidation with brentuximab vedotin for high-risk Hodgkin lymphoma after autologous stem cell transplantation. Cancer. 2017;123(19):3763–3771.

- Delea TE, Sharma A, Grossman A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of brentuximab vedotin plus chemotherapy as frontline treatment of stage III or IV classical Hodgkin lymphoma. J Med Econ. 2019;22(2):117–130.

- Huntington SF, von Keudell G, Davidoff AJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of brentuximab vedotin with chemotherapy in newly diagnosed stage III and IV Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(33):3307–3314.

- Friedberg M, Saffran B, Stinson TJ, et al. Evaluation of conflict of interest in economic analyses of new drugs used in oncology. JAMA. 1999;282(15):1453–1457.