Abstract

Objective

The aim of this post-hoc analysis was to assess the impact of lurasidone monotherapy on functional impairment, productivity, and associated indirect costs in patients with bipolar depression.

Methods

Data were analyzed from a 6-week randomized, double-blind (DB; NCT00868699), placebo-controlled trial of lurasidone monotherapy and a 6-month open label extension (OLE; NCT00868959) study. Patients with bipolar depression who completed the 6-week DB trial were subsequently enrolled in the OLE. Analysis of the OLE was limited to patients who either continued lurasidone (LUR-LUR) or switched from placebo to lurasidone monotherapy (PBO-LUR). The Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS), which measures functional impairment and productivity, was collected at DB baseline, DB week 6/OLE baseline, OLE month 3, and OLE month 6. Annual indirect costs were calculated based on days lost or unproductive from work/school due to symptoms. Effect sizes (ES) in functioning and days lost/unproductive were reported for the DB trial and mean changes for the OLE.

Results

A total of 485 patients were enrolled in the DB trial (lurasidone: n = 323; placebo: n = 162) and 316 were in the lurasidone monotherapy group during the OLE (LUR-LUR: n = 210; PBO-LUR: n = 106). In the DB trial, improvements in functioning (work: ES = 0.36, p = .0071; social: ES = 0.55, p < .0001; family: ES = 0.50, p < .0001) were significantly greater for lurasidone compared to placebo. Reductions in days lost (ES = 0.33, p = .0050) and unproductive (ES = 0.45, p = .0001) were significantly higher for lurasidone vs. placebo. This resulted in a greater reduction in indirect costs for lurasidone vs. placebo (least squares mean (standard error) = −$32,322 ($2,100) vs. −$20,091 ($2,838)). Improvements in functioning and productivity were sustained during the 6-month OLE for both LUR-LUR and PBO-LUR.

Conclusions

Lurasidone monotherapy for the treatment of bipolar depression significantly improved functioning and reduced indirect costs vs. placebo at week 6. Significant improvements in functioning and productivity were sustained for 6 months for both LUR-LUR and PBO-LUR.

Introduction

Bipolar disorder is a chronic mood disorder characterized by recurring manic or hypomanic episodes alternating with major depressive episodesCitation1. Bipolar disorder affects 2.8% of the US adult population annuallyCitation2 with an annual economic burden greater than $195 billionCitation3.

Approximately 60% of patients with bipolar disorder experience decreased functioningCitation4. Even when patients are euthymic, a high proportion of patients with bipolar disorder experience functional impairment across occupational (66%), cognitive (49%), autonomy (43%), interpersonal relationships (42%), leisure (29%), and financial (29%) domainsCitation5. Decreases in functioning may start before the first episode and may continue to decline over timeCitation6.

The economic burden of bipolar disorder is driven by indirect costs such as unemployment and productivity loss of patients and caregiversCitation3,Citation7. Up to 80% of patients with bipolar disorder have missed work due to bipolar disorder, and 30–40% have prolonged periods of unemployment, which are often associated with depressive episodesCitation8,Citation9. Patients with bipolar I disorder spend the majority of their symptomatic time (70%) in the depressed phase of the illness (bipolar depression)Citation10.

Lurasidone is an atypical antipsychotic approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of major depressive episodes associated with bipolar I disorder (bipolar depression) in pediatric (10–17 years) and adult patients as monotherapy and as adjunctive therapy with lithium or valproate in adultsCitation11. The antidepressant effects of lurasidone are believed to be mediated by a high binding affinity for serotonin 5-HT7 receptors as an antagonistCitation12. The safety and efficacy of lurasidone have been previously reportedCitation13.

Change in functioning measured by the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS), a commonly used assessment of functional impairment across multiple domains as well as productivity lossCitation14, was assessed as a secondary outcome measure in the 6-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind (DB), placebo-controlled trials and the 6-month open-label extension (OLE) of lurasidone. Post-hoc analysis of trial data showed that the SDS total score improved with lurasidone monotherapy vs. placebo at week 6Citation15. The use of lurasidone monotherapy during the OLE was also associated with improved SDS total scores in patients who continued or switched to lurasidone monotherapyCitation16.

Although changes in overall functioning are important in demonstrating the effectiveness of bipolar disorder treatment, changes in functioning domains and productivity are also informative, particularly for quantifying the economic burden. The aims of this post-hoc analysis were to evaluate the impact of lurasidone monotherapy on functional impairment domains and productivity and to estimate the indirect costs due to productivity loss in patients with bipolar depression.

Methods

Data source

This post-hoc analysis examined data from the 6-week DB trial of lurasidone monotherapy for the treatment of bipolar depression (NCT00868699) and the 6-month OLE (NCT00868959). The analysis used the intention-to-treat population. The DB trial enrolled patients with a diagnosis (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th Edition with Text Revision) of bipolar I disorder experiencing a major depressive episode who were 18–75 years old and treated in an outpatient setting. Patients were randomized to lurasidone monotherapy (LUR) or placebo (PBO). Patients who completed the DB trial and who were judged by the Investigator to be suitable for participation were able to comply with the protocol, were not at imminent risk of suicide or injury to self or others, and had a Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) item-10 score (suicidal thoughts) ≤3 at OLE baseline could subsequently enroll in the OLE. Analysis of the OLE sample was limited to patients who continued lurasidone monotherapy (LUR-LUR) or switched from placebo to lurasidone monotherapy (PBO-LUR) during the OLE. The full inclusion and exclusion criteria have been previously reportedCitation13,Citation16.

Both the DB trial and the OLE were approved by Institutional Review Boards for all study sites. The studies were conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practices guidelines and ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The studies were reviewed and monitored by an independent data and safety monitoring board. All patients reviewed and signed informed consent documents.

Outcomes and other variables

The SDS is a 5-item self-report tool that assesses functional impairment in three inter-related domains: work/school activities, social functioning, and family relationships and has been validated for use in patients with bipolar disorderCitation14,Citation17. Two additional questions capture the number of days over the last week that was lost (missed school or work or were unable to carry out daily responsibilities) or unproductive (productivity was reduced at school or work or in daily responsibilities) due to symptoms. The SDS total score consists of three items including work/school, social life, and family life/home responsibilities (item score from 0 to 10 with a higher score indicating greater impairment; composite total score 0–30 with a higher score indicating greater impairment). The SDS was a secondary endpoint in the DB trial and OLE and was collected at DB baseline, DB week 6/OLE baseline, OLE month 3, and OLE month 6.

Indirect costs were estimated using the human capital approach, which measures productivity loss in terms of lost earningsCitation18. Therefore, days lost and days unproductive from the DB trial were multiplied by wages and benefits to calculate indirect costs. Patients were assumed to miss 8 h per day for days lost and 3.4 h per day for days unproductive (weighted at 42.98%Citation19). Additional information about the weight for unproductive days is included in the online appendix. The total number of days lost and days unproductive from work/school was capped at 7 days/week. Average hourly compensation ($39.01 per hour), including both wages and benefits, was obtained from the US Bureau of Labor StatisticsCitation20. Annual indirect costs were calculated for 50 weeks/year. Patient demographic and clinical characteristics included age, sex, race, ethnicity, geographic region, age at onset of bipolar I disorder, and duration of bipolar depression from the onset of current episode at DB baseline.

Statistical analysis

SDS total score results have been previously reported by Loebel et al.Citation13 and Ketter et al.Citation16 but were included in this analysis for completeness. Patient characteristics are described at DB baseline with means and standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables and counts and proportions for categorical variables. The mean and SD of the SDS total and item scores were calculated at DB baseline, DB week 6/OLE baseline, OLE month 3, and OLE month 6 for the observed cases. The mean and SD of SDS total and item scores were also calculated using the last observation carried forward (LOCF) for comparison at OLE month 6. For the analysis of the DB trial, the least-squares (LS) mean change in SDS total and item scores from DB baseline to DB week 6 was evaluated using an analysis of covariance model with fixed effects for the treatment group, pooled study center, and baseline score as covariates. The standard error (SE) of the LS mean change was reported. Cohen’s d effect sizes (ES) were calculatedCitation21. Commonly used cut-offs for ES are 0.2 for small, 0.5 for moderate, and 0.8 for largeCitation21. For the analysis of the OLE, the mean change in SDS total and item scores from OLE baseline to month 6 were reported for the cohorts that continued lurasidone monotherapy and switched from placebo to lurasidone monotherapy. Mean changes were calculated in patients with observed values at both time points. The 95% confidence interval (CI) of the mean change was reported. All analyses were conducted using SAS software v9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Statistical significance was defined as p-value <.05. No multiple comparison adjustments were used because of the exploratory nature of the post-hoc analysis.

Results

Patient characteristics

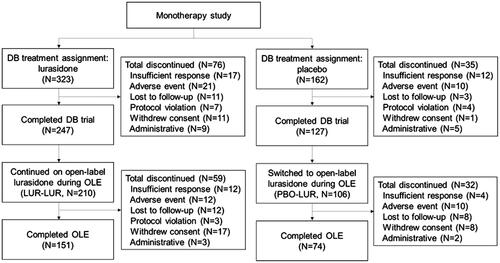

Among the 485 patients randomized to lurasidone monotherapy or placebo in the DB trial (LUR: n = 323, PBO: n = 162), 316 (65.2%) patients completed the DB trial and continued (LUR-LUR: n = 210) or switched (PBO-LUR: n = 106) to lurasidone monotherapy during the OLE (). Over half of the DB trial and OLE participants were female, and the average age was 41–42 years at DB baseline ().

Figure 1. Flow diagram. Abbreviations. DB, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial; LUR-LUR, lurasidone-lurasidone; N, sample size; OLE, open-label extension; PBO-LUR, placebo-lurasidone.

Table 1. Patient demographics and clinical characteristics at 6-week double-blind trial baseline.

6-week double-blind trial (lurasidone vs. placebo)

The average SDS total score improved from 19.7 to 9.6 for patients in the lurasidone group (LS mean change (SE) = −10.8 (0.6)) and from 19.8 to 12.9 for patients in the placebo group (LS mean change (SE) = −7.6 (0.8)) during the DB trial (ES = 0.49, p-value = .0003) ().

Table 2. Mean changes in SDS total and item scores during 6-week double-blind trial.

The LS mean change (SE) from baseline to week 6 in work/school impairment was significantly greater in lurasidone (−3.4 (0.2)) compared to placebo (−2.5 (0.3)) during the DB trial (ES = 0.36, p-value = .0071). Similar trends occurred for social life impairment (−3.6 (0.2) vs. −2.3 (0.2); ES = 0.55, p-value < .0001) and family life/home responsibilities impairment (−3.5 (0.2) vs. −2.3 (0.2); ES = 0.50, p-value < .0001).

Average weekly days lost decreased from 2.7 to 1.1 for patients in the lurasidone group (LS mean change (SE) = −1.6 (0.1)) and from 2.7 to 1.6 for patients in the placebo group (LS mean change (SE) = −1.0 (0.2)) during the DB trial (ES = 0.33, p = .0050). Average weekly days unproductive decreased from 4.5 to 2.1 for patients in the lurasidone group (LS mean change (SE) = −2.3 (0.2)) and from 4.0 to 2.9 for patients in the placebo group (LS mean change (SE) = −1.4 (0.2)) during the DB trial (ES = 0.45, p = .0001).

6-month open label extension

The average SDS total score improved from 9.3 to 5.5 for LUR-LUR (mean change (95% CI) = −3.4 (−4.6, −2.2)) and from 12.6 to 5.7 for PBO-LUR (mean change (95% CI) = −6.2 (−8.1, −4.3)) during the OLE ().

Table 3. Mean changes in SDS total and item scores during 6-week double-blind trial and 6-month open-label extension in patients who continued or switched to open-label lurasidone monotherapy.

The average work/school score improved for LUR-LUR (mean change (95% CI) = −1.2 (−1.7, −0.8)) and for PBO-LUR (mean change (95% CI) = −2.0 (−2.7, −1.3)). Similar changes occurred for social life (LUR-LUR = −1.0 (−1.4, −0.7), PBO-LUR = −2.1 (−2.8, −1.5)) and family life/home responsibilities (LUR-LUR = −1.0 (−1.4, −0.6), PBO-LUR = −1.9 (−2.5, −1.3)) scores. Figures for SDS total, work/school, social life, and family life scores are included in the Online Appendix.

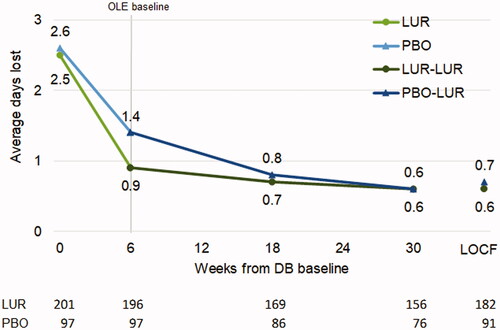

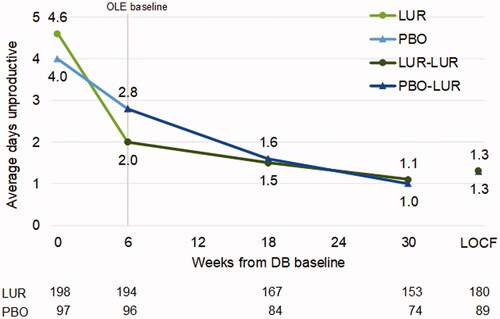

Treatment with lurasidone during the DB trial was associated with a more rapid decrease in days lost () and days unproductive () followed by a sustained improvement in productivity during the OLE. Patients switching from placebo to lurasidone during the OLE reached similar levels of productivity by OLE month 3 (i.e. 18 weeks from DB baseline).

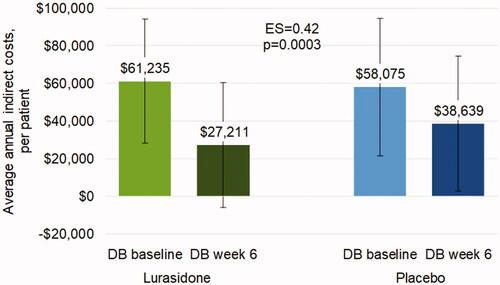

Indirect costs

The average annual indirect costs due to days lost and days unproductive were approximately $60,000 at DB baseline (lurasidone: mean (SD) = $61,235 ($33,071); placebo: mean (SD) = $58,075 ($36,644)). Annual indirect costs significantly decreased with lurasidone vs. placebo at DB week 6 (LS mean change (SE) = −$32,322 ($2,100) vs. −$20,091 ($2,838); ES = 0.42, p = .0003) (). Indirect costs were sustained at a lower level for patients who continued treatment with lurasidone during the OLE and were no longer significantly different between LUR-LUR and PBO-LUR at OLE month 6 (not shown).

Discussion

Treatment with lurasidone monotherapy improved functioning, increased productivity, and reduced indirect costs at week 6 compared to placebo in patients with bipolar depression. With continued treatment with lurasidone, the improvements in total and sub-domain functioning, as well as increases in productivity, were sustained during the 6-month OLE. Both functioning and productivity for patients who switched from placebo to lurasidone monotherapy converged on outcomes for patients who continued lurasidone monotherapy.

Functional recovery is an integral component of bipolar disorder treatment but may lag behind symptomatic recovery due, in part, to residual depressive symptomsCitation5. Patients with a history of depression (including bipolar depression) and caregivers and healthcare professionals who care for such patients report a wide array of symptoms and functioning domains (elementary, social, professional, complex) that could benefit from depression treatmentCitation22. Therefore, the longer-term changes in SDS item scores reported in this post-hoc analysis are an important addition to existing evidence of the functioning and productivity benefits of lurasidone monotherapy.

Occupational functional impairment has been reported to be the most prevalent functioning domain limitation (65.6%) in patients with bipolar disorderCitation5. This post-hoc analysis reported significant impairment in work/school functioning at DB baseline (average item scores >5Citation14). We are not aware of minimally clinically important differences for the SDS functioning domains. However, continuous treatment with lurasidone monotherapy was associated with an improvement in mean work/school functioning scores of over 70% from DB baseline to OLE month 6 (approximately 30 weeks). Patients with fewer occupational functional limitations may be able to return to full- or part-time employment and reduce the economic burden of bipolar disorder associated with the decrease in productivity.

This post-hoc analysis also reported significant impairment in social and family life functioning at DB baseline. Impairment in leisure activities (social life) and home responsibilities (family life) may impact a patient’s life satisfaction, quality of life, and ability to live independently. A separate post-hoc analysis explored the longer-term impact of lurasidone monotherapy on life satisfaction as well as the quality of lifeCitation23. In this analysis, the effects of lurasidone monotherapy vs. placebo at DB week 6 were greater for social and family life compared to work/school, suggesting that social and family life impairment may improve faster than work/school impairment with a decrease in symptom burden. Similar to the work/school functioning scores, social and family life functioning scores in patients who continued lurasidone monotherapy during the OLE improved over 70% from DB baseline to OLE month 6. Future analysis should examine the association between work/school, social, and family life functioning.

The economic burden of bipolar disorder on US employers is driven by indirect costs due to days lost and days unproductive ($14.1 billion per year)Citation24. Compared to employees without bipolar disorder, the indirect costs of employees with bipolar disorder were 2.5 times greater largely due to greater days lost (11.5 days/year, p < .05)Citation24,Citation25. Treatment with lurasidone monotherapy vs. placebo decreased days lost by 0.4 days/week and days unproductive by 1.4 days/week at week 6. Decreases were sustained for those who continued lurasidone monotherapy and converged for those who switched from placebo to lurasidone monotherapy during the OLE. Earlier treatment of bipolar disorder was associated with a more rapid improvement in productivity, which may be associated with decreases in indirect costs.

Improvements in overall functioning among patients with bipolar depression have also been reported in a Japanese 6-week DB trial of lurasidone monotherapyCitation26, three 8-week trials of quetiapine monotherapyCitation27, and an 8-week DB trial of cariprazineCitation28. Because of the importance of functional recovery in bipolar disorder treatment, assessments of bipolar disorder treatments should include measures of functioningCitation29. The relative effect of lurasidone on functioning and productivity compared to other atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of bipolar depression has not been estimated. Future analysis could indirectly compare the functioning and productivity effects of lurasidone and other atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of bipolar depression.

While symptomatic remission in patients with bipolar depression generally precedes functional improvements, the relationship between bipolar depression treatment and its effect on depressive symptoms and functioning is complex. Path analysis, a method to assess the causal pathways and effects of multiple variables on an outcome, has been used to estimate the direct and indirect effects of treatment on functioning in patients with bipolar disorderCitation15,Citation30. An earlier post-hoc analysis of the 6-week lurasidone monotherapy DB trial reported that lurasidone monotherapy had both a direct effect on functional impairment and an indirect effect via improvement in depressive symptomsCitation15.

There were limitations associated with this analysis. First, the DB trial and OLE were conducted among patients with major depressive episodes associated with bipolar I disorder, so the results may not be generalizable to patients with bipolar II disorder. Second, using a different assessment of social functioning than SDS may produce different results. Third, functional impairment and productivity were patient-reported and therefore subject to the patient recall of the last 7 days. Fourth, analyses of productivity were not limited to patients who were employed because employment status was not collected, so indirect costs may be overestimated. However, the lack of employment status data should not differentially affect the lurasidone and placebo groups. Fifth, the analysis of the OLE sample was limited to patients in the DB trial who continued or switched to lurasidone monotherapy. Results may be different for patients who did not participate in the OLE. Finally, direct product costs and side effects were not assessed in this study but could be included in further research to evaluate the total costs among patients with bipolar depression.

Conclusions

Lurasidone monotherapy for the treatment of bipolar depression significantly improved functioning and reduced days unproductive at DB week 6 compared to placebo. Significant improvements in functioning and productivity for patients who continued lurasidone monotherapy were sustained during the OLE. Outcomes for patients who switched to lurasidone monotherapy converged on those for patients who continued lurasidone monotherapy. Understanding the functioning and productivity benefits of lurasidone monotherapy may help reduce the functional and economic burden of bipolar depression.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This post-hoc analysis was funded by Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Declaration of financial/other interests

XN, CD, QF, YM, SB, and MT are employees of Sunovion. VD is an employee of IQVIA, which received funding from Sunovion to conduct this analysis.

The peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work. One of the reviewers has received manuscript or speaker’s fees from Astellas, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Elsevier Japan, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Kyowa Yakuhin, Lundbeck, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Nihon Medi-Physics, Novartis, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Shionogi, Shire, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Tsumura, Wiley Japan, and Yoshitomi Yakuhin, and research grants from Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Eisai, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma and Shionogi. The other peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in the design of the post-hoc analysis, data analysis, interpretation of results, drafting and critical revision of the manuscript, and providing a final review.

Previous presentations

An earlier version of this work was presented as a poster at the 2021 Neuroscience Education Institute Congress (Colorado Springs, CO; 4–7 November 2021) and the 2021 US Psych Congress (San Antonio, TX; 29 October–1 November).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (87 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of this study as well as the members of the Lurasidone Bipolar Disorder Study Group. We also thank Barbara Blaylock, PhD from Blaylock Health Economics LLC for providing medical writing support.

Data availability statement

This post-hoc analysis used confidential clinical trial data, which are not publicly available.

References

- Carvalho AF, Firth J, Vieta E. Bipolar disorder. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(1):58–66.

- Merikangas KR, Jin R, He JP, et al. Prevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in the world mental health survey initiative. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(3):241–251.

- Bessonova L, Ogden K, Doane MJ, et al. The economic burden of bipolar disorder in the United States: a systematic literature review. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2020;12:481–497.

- MacQueen GM, Young LT, Joffe RT. A review of psychosocial outcome in patients with bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;103(3):163–170.

- Léda-Rêgo G, Bezerra-Filho S, Miranda-Scippa Â. Functioning in euthymic patients with bipolar disorder: a systematic review and Meta-analysis using the functioning assessment short test. Bipolar Disord. 2020;22(6):569–581.

- Grande I, Berk M, Birmaher B, et al. Bipolar disorder. Lancet. 2016;387(10027):1561–1572.

- Cloutier M, Greene M, Guerin A, et al. The economic burden of bipolar I disorder in the United States in 2015. J Affect Disord. 2018;226:45–51.

- Baldessarini RJ, Vázquez GH, Tondo L. Bipolar depression: a major unsolved challenge. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2020;8(1):1.

- Zimmerman M, Galione JN, Chelminski I, et al. Sustained unemployment in psychiatric outpatients with bipolar disorder: frequency and association with demographic variables and comorbid disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12(7):720–726.

- Forte A, Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L, et al. Long-term morbidity in bipolar-I, bipolar-II, and unipolar major depressive disorders. J Affect Disord. 2015;178:71–78.

- Latuda (lurasidone) [package insert]. Marlborough (MA): Sunovion Parmaceuticals Inc.; 2018.

- Loebel A, Citrome L. Lurasidone: a novel antipsychotic agent for the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar depression. BJPsych Bull. 2015;39(5):237–241.

- Loebel A, Cucchiaro J, Silva R, et al. Lurasidone monotherapy in the treatment of bipolar I depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(2):160–168.

- Sheehan D. The anxiety disease. New York (NY): Scribners; 1983.

- Rajagopalan K, Bacci ED, Wyrwich KW, et al. The direct and indirect effects of lurasidone monotherapy on functional improvement among patients with bipolar depression: results from a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2016;4(1):7.

- Ketter TA, Sarma K, Silva R, et al. Lurasidone in the long-term treatment of patients with bipolar disorder: a 24-week open-label extension study. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33(5):424–434.

- Arbuckle R, Frye MA, Brecher M, et al. The psychometric validation of the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) in patients with bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2009;165(1–2):163–174.

- Zhou ZY, Koerper MA, Johnson KA, et al. Burden of illness: direct and indirect costs among persons with hemophilia a in the United States. J Med Econ. 2015;18(6):457–465.

- Benson C, Singer D, Carpinella CM, et al. The health-related quality of life, work productivity, healthcare resource utilization, and economic burden associated with levels of suicidal ideation among patients self-reporting moderately severe or severe major depressive disorder in a national survey. NDT. 2021;17:111–123.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. Employer costs for employee compensation - March 2021. Washington (DC): US Department of Labor; 2021.

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York (NY): Routledge Academic; 1988.

- Chevance A, Ravaud P, Tomlinson A, et al. Identifying outcomes for depression that matter to patients, informal caregivers, and health-care professionals: qualitative content analysis of a large international online survey. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(8):692–702.

- Fan Q, Dembek C, Divino V, et al. The impact of lurasidone on health-related quality of life in patients with bipolar depression: a post-hoc analysis of a 6-month open-label extension study [Abstract]. NEI Conference. 2021 Nov 4-7; Colorado Springs, CO.

- Laxman KE, Lovibond KS, Hassan MK. Impact of bipolar disorder in employed populations. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(11):757–764.

- Kleinman NL, Brook RA, Rajagopalan K, et al. Lost time, absence costs, and reduced productivity output for employees with bipolar disorder. J Occup Environ Med. 2005;47(11):1117–1124.

- Kato T, Ishigooka J, Miyajima M, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of lurasidone monotherapy for the treatment of bipolar I depression. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020;74(12):635–644.

- Suttajit S, Srisurapanont M, Maneeton N, et al. Quetiapine for acute bipolar depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2014;8:827–838.

- Vieta E, Calabrese JR, Whelan J, et al. The efficacy of cariprazine on function in patients with bipolar depression: a post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(9):1635–1643.

- Gitlin MJ, Miklowitz DJ. The difficult lives of individuals with bipolar disorder: a review of functional outcomes and their implications for treatment. J Affect Disord. 2017;209:147–154.

- Cotrena C, Damiani Branco L, Milman Shansis F, et al. Influence of modifiable and non-modifiable variables on functioning in bipolar disorder: a path analytical study. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2020;24(4):398–406.