Abstract

Objectives

To gain a better understanding of the characteristics of patients with a hospital encounter for major depressive disorder (MDD) and evaluate associated hospital resource utilization, hospital charges and costs, and hospital re-encounters.

Methods

Adult patients with a hospital encounter (i.e. emergency department [ED] visit only or inpatient admission) with MDD as the primary discharge diagnosis (index event) during July 2018‒March 2019 were selected from the Premier Healthcare Database. Patient characteristics, hospital resource utilization, and hospital charges and costs were evaluated during index events. During a 12-month follow-up, hospital re-encounters (MDD-related and all-cause ED visit only or inpatient readmissions) were examined.

Results

The study population included 77,178 patients with an index hospital encounter (ED visit only: 49.9%; inpatient admission: 50.1%) for MDD. The most common secondary mental health-related diagnosis was suicidal ideation/behavior, which was recorded in 51.8% of patients. The mean age was 38.2 years, 53.0% were female, and 72.1% were Caucasian. Among patients with an ED visit only, the mean index hospital charges and costs were $3,608 and $639, respectively. Among those with inpatient admissions, the mean length of stay was 4.9 days, and the mean index hospital charges and costs were $17,107 and $6,095, respectively. During the 12-month follow-up, 13.3% of patients in the overall study population had an MDD-related hospital re-encounter (primary or secondary discharge diagnosis code indicating MDD); nearly one-third (31.3%) occurred within 30 days post-discharge. During the follow-up, 28.1% had an all-cause hospital re-encounter with 29.7% having occurred within 30 days post-discharge.

Limitations

Due to constraints of the Premier Healthcare Database, healthcare resource utilization and costs outside of the hospital could not be evaluated.

Conclusions

Patients with a hospital encounter for MDD are relatively young, commonly have suicidal ideation/behavior, utilize substantial hospital resources, and have a high risk for a hospital re-encounter in the 30 days post-discharge.

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a common mental health condition estimated to affect more than 300 million people worldwideCitation1. Based on data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), in the United States from 2005 to 2019, the percentage of adults (≥18 years and older) with a major depressive episode (MDE) in the past year increased from 6.6% to 7.8% (19.4 million adults)Citation2. Moreover, the percentage with a past-year MDE with severe impairment rose from 4.0% in 2009 to 5.3% (13.1 million adults) in 2019Citation2. In the NSDUH, severe impairment is defined as high scores (>7 on an 11-point scale) in 4 domains: home management, work, close relationships with others, and social lifeCitation3.

In addition to causing significant disability, MDD is frequently associated with suicidal ideation (SI) and behaviorCitation4,Citation5. Also based on NSDUH data, from 2009 to 2017, the prevalence of co-occurring past-year MDE and SI increased by nearly 30%, from 1.7% to 2.2% among US adultsCitation5. Patients with MDD who are assessed to be at imminent risk for suicide are considered to be in a psychiatric emergency and are frequently hospitalizedCitation6. A nationally representative study of adult inpatient admissions (N = 10,805,833) in the US between 2014 and 2015 found that 1.3% (N = 136,704) were associated with a primary discharge diagnosis of MDD; 54% of these patients also had a secondary diagnosis of SI and 6% had a suicide attempt (SA)Citation6. Other large national studies in the US have found that emergency department (ED) visits for MDD and SI or SA have been increasing in recent yearsCitation7,Citation8. According to data from the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS), from 2006 to 2014, ED visits for depression increased by 26%, with one-half of patients in 2014 who first received care in the ED being admitted as inpatientsCitation7. Also based on NEDS, in a statistical brief of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), it was reported that from 2008 to 2017, the frequency of ED visits for SI or SA increased for all age groups of adults in the US and in 2017 approximately two-thirds of such ED visits led to an inpatient admission or transfer to another facility (e.g. short-term hospital)Citation8.

The rising prevalence of MDD and/or SI or SA and the associated growing hospital burden in the US learned from these past studies with data from 2006 up to 2017 necessitates actions to improve the care of patients with MDD in a psychiatric emergency. To inform healthcare systems, policymakers, and payers for developing the best strategies to improve the care of this patient population, it is important to have a better understanding of the characteristics of patients with MDD in a psychiatric emergency and their outcomes, in addition to accompanying healthcare costs during a more recent time frame. To generate such real-world evidence, this study used the most recent data available from a large national hospital database to evaluate the characteristics of patients with a hospital encounter primarily for MDD, either an ED visit only or an inpatient admission, and also examined the associated hospital resource utilization, hospital charges and costs, and hospital re-encounters post-discharge.

Methods

Study design and data source

This study was a retrospective cohort analysis of patients with a hospital encounter primarily for MDD who were selected from the US-based, nationally representative Premier Healthcare hospital database (Premier Inc., Charlotte, NC). The Premier database is the largest US hospital database with detailed daily inpatient admission information from >1,000 contributing hospitals/healthcare systems. It captures >120 million hospital discharges and >890 million hospital outpatient visits from >1,000 acute care hospitals, representing approximately 25% of all hospital encounters in the US. Data elements include demographics, visit-level information, diagnoses, hospital characteristics, and detailed drug use information. Medical information from >230 million unique patients available in the Premier database comes from records collected for hospital administrative purposes at the hospital level. All data are de-identified and fully compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

Study population

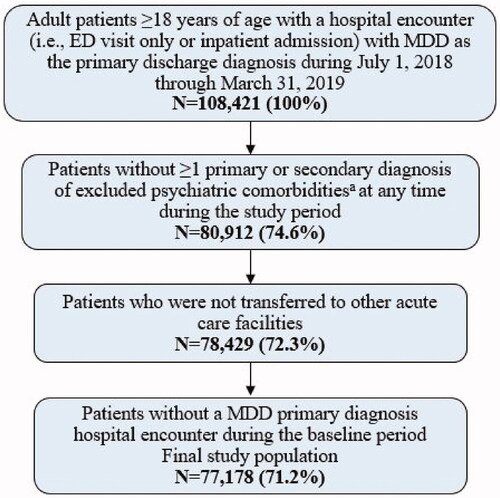

Adult patients ≥18 years of age with a hospital encounter (i.e. ED visit only and then discharged or inpatient admission) with MDD as the primary discharge diagnosis during July 1, 2018 through March 31, 2019 (index identification period) were selected from the Premier database. The earliest ED visit or inpatient admission for a patient that occurred during the index identification period was defined as the index hospital encounter event and the discharge date was assigned as the index date. Patients who had ≥1 primary or secondary diagnosis of the psychiatric comorbidities, including bipolar disorder/manic depression, dementia, intellectual disability, schizophrenia, schizotypal, delusional, cluster b personality disorders, substance-induced mood disorders and other non-mood psychotic disorders, at any time during the study period were excluded from the study population. To capture the complete records of the index hospital encounters, patients who had a discharge status from their index hospital encounter indicating a transfer from or to other acute care facilities were additionally excluded from the final study population since such facilities are not included in the data source. Lastly, patients who had a hospital encounter with a primary or secondary diagnosis of MDD recorded during the 6 months prior to index event (baseline period) were excluded from the study population. Patients who met the study criteria were grouped into a final analysis cohort and additionally stratified by the index hospital encounter setting (i.e. ED visit only or inpatient admission) for study measurements. The process of patient selection is shown in .

Figure 1. Process of patient selection. aExcluded psychiatric comorbidities were bipolar disorder/manic depression, dementia, intellectual disability, schizophrenia, schizotypal, delusional, cluster b personality disorders, substance induced mood disorders and other non-mood psychotic disorders. Abbreviation. MDD, Major depressive disorder.

Patient demographics, hospital characteristics, and patient clinical characteristics

Patient demographics, including age, sex, marital status, race, and health insurance type, and hospital characteristics were evaluated from index hospital encounter records. Patient clinical characteristics were evaluated from the diagnosis codes at either the index hospital encounter or during the 6-month baseline period. The patient clinical characteristics evaluated included Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score and prevalence of CCI comorbid conditionsCitation9, and prevalence of mental health-related conditions.

Measured hospital resource utilization and charges and costs of index hospital encounters

The total hospital charges and costs were determined for index hospital encounters. The total inpatient length of stay (LOS) was determined for index inpatient admissions. Hospital charge data reflect the amounts hospitals charged payers for the hospital care and may not reflect the final paid/reimbursement amount. Hospital cost data reflect the actual costs incurred by hospitals to provide healthcare services. All hospital charge and cost data reported were from the hospital perspective and were inflation-adjusted to 2020 USD.

Measured hospital re-encounter outcomes

During a 12-month follow-up post-discharge of patients’ index events, hospital re-encounters (MDD-related and all-cause) were evaluated, in addition to the associated total inpatient LOS among those with inpatient readmissions, and hospital charges and costs with a breakdown by hospital re-encounter type (any hospital re-encounter, ED visit only re-encounter and then discharged, and inpatient readmission). An MDD-related re-encounter was identified by a primary or secondary discharge diagnosis code indicating MDD. The Premier database attaches a unique ID to each patient at one specific hospital system, which allows hospital encounters to be linked to hospital re-encounters in the follow-up by the same patient, but only if the re-encounter occurred at the same hospital system.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to describe patient demographics, hospital characteristics, patient clinical characteristics, index inpatient hospital LOS and index hospital charges and costs, and hospital re-encounter measurements. The count and percentage of the total were reported for all categorical variables. The mean and standard deviation (SD) were reported for all continuous variables. All statistical analyses were carried out using SAS 9.4.

Results

Study population

The overall study population included 77,178 patients who had an index hospital encounter with MDD as the primary diagnosis (i.e. psychiatric emergency); 49.9% (N = 38,524) had an ED visit only and 50.1% (N = 38,654) had an inpatient admission.

Patient demographics, hospital characteristics, and patient clinical characteristics

Patient demographics and hospital characteristics are shown in . Among the overall study population, the mean age was 38.2 years, with 66.2% 18–44 years of age; 53.0% were female, 72.1% were Caucasian, 15.4% were Black/African American, and 12.4% were other races. Most (77.8%) were not married or had unknown marital status. Patients with an ED visit only were slightly younger than those with inpatient admission. Sex distributions were similar among patients with an ED visit only and those with inpatient admission.

Table 1. Demographic and hospital characteristics of patients with hospital encounters for MDD.

Among the overall study population, approximately one-third (30.6%) were insured by Medicaid, 23.5% had managed care, 14.2% were insured by Medicare, and 10.8% had commercial insurance coverage. A greater proportion of patients with an ED visit only (19.3%) self-paid compared to among those with an inpatient admission (10.1%). Approximately 70% of hospital encounters were in the South and Midwest regions of the US; 85.3% were in urban hospitals and 55.0% were in large-sized hospitals (≥300 beds). Among those patients with an ED visit only, 70.4% were discharged to home and 27.1% were transferred to a non-acute care setting. Most (94.5%) patients with an inpatient admission were discharged to home.

Patient clinical characteristics are shown in . General comorbidity level was low, with an average CCI score of 0.3 for the overall study population, but those with an inpatient admission had a slightly higher average CCI score (0.4) than patients with an ED visit only (0.2). The most prevalent CCI comorbid conditions were pulmonary-related diseases (9.8%) and diabetes without complications (6.8%), which were more prevalent among patients with an inpatient admission than among those with an ED visit only. The most common secondary mental health-related diagnoses were SI and/or SA, which was recorded in 51.8% of the overall study population, and 35.1% of patients with an ED visit only and 68.5% of those with inpatient admissions. Other prevalent mental health-related conditions included anxiety disorder and substance abuse and addictive disorders, and they were also more prevalent among patients with inpatient admission.

Table 2. Clinical characteristics of patients with hospital encounters for MDD.

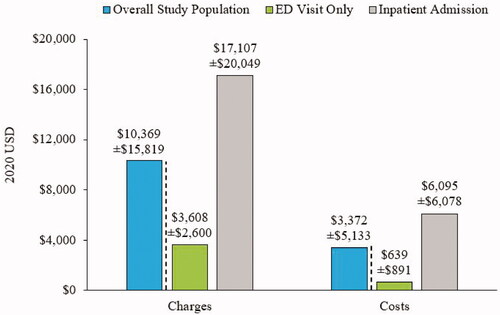

Hospital resource utilization and charges and costs of index hospital encounters

Among patients with an ED visit only, mean (SD) hospital charge was $3,608 ($2,600) and the hospital cost was $639 ($891) (); median hospital charge and cost were $3,117 and $502, respectively. Among those with inpatient admissions, mean (SD) hospital LOS, hospital charge, and hospital cost were 4.9 (4.0) days, $17,107 ($20,049), and $6,095 ($6,078), respectively (); median hospital LOS, charge, and cost were 4 days, $11,912, and $4,729, respectively.

Hospital re-encounter outcomes

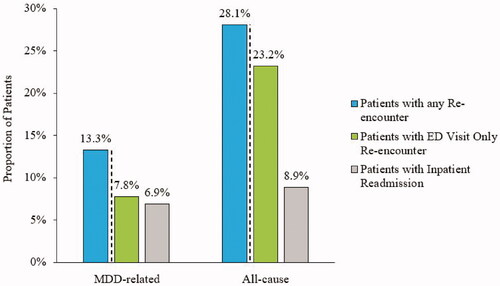

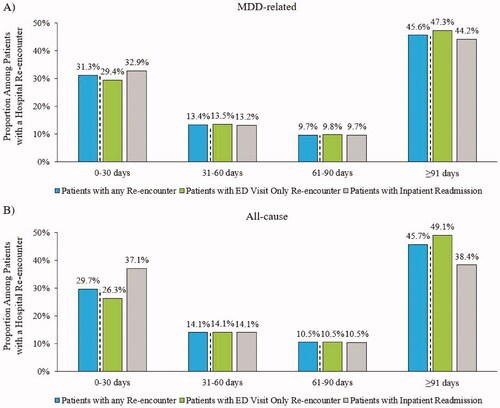

During the 12-month follow-up, 13.3% of patients in the overall study population had an MDD-related hospital re-encounter; 7.8% had an ED visit only re-encounter and 6.9% had inpatient readmission (a patient may have had both an ED visit only re-encounter and inpatient readmission; thus, the sum of the proportions with an ED visit only re-encounter and inpatient readmission may be greater than the percentage of patients with any hospital re-encounters, ). Of all the MDD-related hospital re-encounters, nearly one-third (31.3%) occurred within 30 days following discharge from index hospital encounters; 13.4%, 9.7%, and 45.6% occurred within 31–60 days, 61–90 days, and ≥91 days post-discharge, respectively (). The time distributions of MDD-related hospital re-encounters were generally similar for ED visit-only re-encounters and inpatient readmissions ().

Figure 3. Proportions of patients with any hospital re-encounter, an ED visit only re-encounter, and an inpatient readmission in the follow-up period. A patient may have had both an ED visit only re-encounter and inpatient readmission. Thus, the sum of the proportions with an ED visit only re-encounter and inpatient readmission may be greater than the percentage of patients with any hospital re-encounters. Abbreviations. ED, Emergency department; MDD, Major depressive disorder.

Figure 4. Distribution of time to hospital re-encountersa among patients with A) an MDD-related and B) all-cause hospital re-encounter in the follow-up period. aHospital re-encounters includes ED visit only re-encounters and inpatient readmissions. Abbreviations. ED, Emergency department; MDD, Major depressive disorder.

During the 12-month follow-up, 28.1% of the patients in the overall study population had an all-cause hospital re-encounter; 23.2% had an ED visit only re-encounter and 8.9% had inpatient readmission (); 13.3% of patients had >1 hospital re-encounter. Of all of the all-cause hospital re-encounters, 29.7% occurred within 30 days following discharge from index hospital encounters; 14.1%, 10.5%, and 45.7% occurred within 31–60 days, 61–90 days, and ≥91 days post-discharge, respectively (). The time distributions of all-cause hospital re-encounters were mostly similar for ED visit only re-encounters and inpatient readmissions, with approximately 10% more of inpatient readmissions having occurred within 30-days ().

Other measured outcomes of hospital re-encounters during the 12-month follow-up period are shown in . Almost one-half (47.4%) of all hospital re-encounters during the follow-up period (N = 21,707), were MDD-related; 31.9% of the ED visit only re-encounters were MDD-related, while 80.9% of inpatient readmissions (with or without ED visit re-encounter) were MDD-related.

Table 3. Hospital re-encounter outcomes among patients with any hospital re-encounters during the 12-month follow-up period.

Among patients with any hospital re-encounter, the mean number of MDD-related hospital re-encounters was 0.7 per patient. For an MDD-related ED visit only re-encounter, the mean total hospital charge and cost were $1,718 and $279, respectively. For MDD-related inpatient readmission, the mean total hospital LOS, charge, and cost were 7.8 days, $31,935, and $9,538, respectively.

Among patients with any hospital re-encounter, the mean number of all-cause hospital re-encounters was 2.3 per patient. For an all-cause ED visit only re-encounter, the mean total hospital charge and cost were $7,301 and $1,124, respectively. For all-cause inpatient readmission, the mean total hospital LOS, charge, and cost was 7.9 days, $50,120, and $14,046, respectively.

Discussion

In this real-world analysis from the US hospital perspective, we found that among nearly 80,000 patients with a hospital encounter primarily for MDD, one-half were admitted to the inpatient setting, while the other half were discharged from the ED. This finding is consistent with that observed in the 2014 NEDS of patients with a primary diagnosis of depression or a secondary diagnosis of depression with a primary diagnosis of SI, among which one-half who first received care in the ED was subsequently admitted as inpatientsCitation7. In our study, over one-half (52%) of the overall population had a recorded secondary diagnosis of SI and/or SA; nearly 70% of those with an inpatient admission and approximately one-third of patients with an ED visit only. The prevalence of SI and behavior in this patient population is in the range of that reported by Citrome et al. among patients hospitalized for MDD in the US, which was approximately 60% among those identified from the Premier database (2014–2015 data) and 40% among those identified from the MarketScan administrative healthcare claims databases (2013 data)Citation6.

Notably, we found that the patient population with an initial hospital encounter for MDD during July 2018 through March 31, 2019, was relatively young, with approximately two-thirds being 18 to 44 years of age. In the earlier study conducted by Citrome et al. of patients hospitalized for MDD, just over 50% were 18 to 44 years of age among those identified from the Premier database, while approximately 60% were in this age group among those identified from the Market Scan databaseCitation6. The increasing trend in hospital encounters for MDD potentially linked to SI and behavior among young people in the US aligns with studies based on NSDUH data (2009–2017) that found increasing trends in both the incidence of MDE and SI and behavior among younger adultsCitation5,Citation10.

The findings of this study have also revealed that the costs of hospital encounters primarily for MDD have remained relatively high, which is 2020 USD were on average $639 for an ED visit and $6,095 for inpatient admission. Neslusan et al. conducted a study on hospital resource utilization and re-encounters (ED visit only or inpatient admission), in which only patients with co-occurring MDD and SI were included in the study population (identified between January 1, 2017 and September 30, 2018)Citation11. In this study, the average cost of an ED visit for MDD was $693 and for an inpatient admission for MDD, it was $6,478Citation11. The average cost of an inpatient admission for MDD that we observed is also comparable to that reported by Citrome et al. among patients hospitalized for MDD during 2014 to 2015, which was $6,713Citation6. The average inpatient LOS reported by Citrome et al. was 6.0 daysCitation6, in the study by Neslusan et al., it was 5.1 daysCitation11, and in the current study (July 2018-March 2020 patient data), it was 4.9 days. These studies were all of patients identified from the Premier database and there is potentially a slight trend for a shorter duration in inpatient LOS for patients hospitalized for MDD from 2014 to 2020, in addition to a small decline in inpatient costs. Further study is warranted to determine if in recent years there have been changes in routine inpatient care of patients with MDD.

The frequency of MDD-related hospital re-encounters in this study was 13%. Remarkably, the vast majority (81%) of patients with inpatient readmissions had at least one MDD-related readmission, with an average total hospital cost of $9,538. The frequency of MDD-related hospital re-encounters observed in this study is similar to that found in other studies; Citrome et al. reported an MDD-related hospital readmission rate of 13% during a 1-year follow-upCitation6 and Neslusan et al. reported an overall rate of 12% for an MDD-related hospital re-encounter during 6 months of follow-up and this rate did not change with the initial hospital encounter settingCitation11. Also similar to our study findings, both of these other studies also found MDD-related hospital re-encounter rates to be high in the first 30-days following discharge from an initial hospital encounter for MDDCitation6,Citation11.

Furthermore, a large US claims-based study of 121,065 patients with depression (2015–2018) who had a hospital encounter (ED visit or inpatient admission) for SI or SA, reported re-encounter rates for SI or SA within a year following discharge ranged between 8% and 11% among patients identified from 4 different administrative claims databases; the highest rates of re-encounters occurred within the first-month post-discharge and approximately 50% occurred within 3 monthsCitation12. This study by Cepeda et al. also found rates ranging between 26% and 41% for hospital re-encounter for any cause across the patients identified from the 4 data sourcesCitation12, which is relatively consistent with our finding of 28% for the overall study population identified from a hospital records database. Elevated rates of hospital resource utilization for any cause among patients with MDD/depression have also been reported in previous studiesCitation13,Citation14. Additionally, a study of patients with MDD and at least one physical comorbidity (cardiovascular, metabolic, respiratory, and/or cancer) found 74% higher all-cause healthcare costs for this patient group compared to that of patients without MDD but with at least one physical comorbidity; all-cause healthcare costs were even higher among those with treatment-resistant MDDCitation15. Healthcare resource utilization and the economic burden, including healthcare costs, as well as work-loss-related costs, of patients with treatment-resistant MDD, have also been found to be heightened among those with co-occurring mental health-related comorbidities, such as anxiety and substance abuse disordersCitation16, which afflicted 36% and 31%, respectively, of the current study population. The findings of these latter two studies indicate that MDD, especially when treatment-resistant, may negatively impact the clinical management of physical and other mental health-related comorbiditiesCitation15,Citation16. Further study of the clinical factors of patients with MDD and how they impact healthcare resource utilization, in addition to the risk of a hospital re-encounter is warranted.

The National Committee for Quality Assurance in the US uses the quality-of-care measure of outpatient follow-up within 30 days of discharge after inpatient treatment for mental illnesses or intentional self-harm in the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) Citation17. According to the HEDIS, there has been a decline in recent years (2014–2019) in the use of this quality-of-care measure across members of Medicaid, Medicare, and Commercial hospital/healthcare systemsCitation17. The high rates of MDD-related and all-cause hospital re-encounters, especially in the first 30 days after discharge, as well as the substantial costs associated with re-encounters, that we observed in this study population with MDD further emphasize that improvements are needed nationwide in the management and treatment of MDD.

Limitations

The findings of this study should be interpreted in the context of certain limitations. This study was conducted using a hospital-based database, therefore outpatient healthcare resource utilization, as well as absenteeism/presenteeism, could not be evaluated. It is also important to note that because of this limitation of the data source, additional healthcare resource utilization and outcomes of the 27% of patients with an ED visit only who were transferred to a non-acute care setting (e.g. outpatient preventive care center, long-term care center, etc.) could not be fully evaluated in this study. Furthermore, since only patients who had a hospital re-encounter at the same hospital/healthcare system in the Premier database are captured as patients with a re-encounter, the hospital re-encounter rates may have been under-estimated in this study. However, the Premier database has been frequently used by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and by the overall clinical community for research on hospital encounters, readmissions, and subsequent ED visits in the US, with over 600 scientific studies published in peer-reviewed journals (2009 through Q1 of 2019) having utilized the data sourceCitation18,Citation19. This study was conducted prior to the coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, which likely has impacted the mental health of many people throughout the world, especially those with pre-existing mental health conditions. It will be important in future studies to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on those individuals with MDD, including on how it may have affected disease prevalence and severity, as well as accompanying healthcare resource utilization and costs.

Although in this study we had nationwide representation, the distribution of contributing hospitals to the Premier database is regionally disproportionate, with the South and Midwest regions having higher representation in the data source than the West and Northeast. In this study, we excluded those patients who were discharged to other acute care settings to make sure we captured the most complete patient records and thus, the study findings may not generalize to such a patient population. Regarding the reporting of hospital charges and costs, since such data may be skewed by charge/cost outliers (i.e. very high charges/costs for some patients)Citation20, we show both mean and median values. Mean values are generally higher than median values because they are more affected by outlier charge/cost data points, but both values are important from the hospital and payer perspectives. Finally, hospital records in the data source are collected for administrative purposes and not for research and may be subject to potential coding errors, which may occur to a greater extent with the challenge to accurately code SI and behavior.

Conclusions

In this large real-world analysis of patients with a hospital encounter primarily for MDD, nearly 70% were 18 to 44 years of age, more than half (52%) were also diagnosed with suicidal ideation or behavior, and approximately 50% were admitted to the inpatient setting. The substantial utilization of hospital resources and associated costs and high risk for a hospital re-encounter within the 30 days post-discharge are indicative of a significant unmet need for appropriate and effective treatments for patients with MDD in a psychiatric emergency, as well as for improved continuity of care.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Sponsorship for this study and preparation of this manuscript was provided by Janssen Global Services, LLC.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

QZ, MO’H, CM, SB, MM, KJ, and JA are employees of Janssen, LLC. MLS and JL are employees of Novosys Health, which received research funds from Janssen, LLC in connection with conducting this study and preparation of this manuscript.

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

QZ, MO’H, CM, SB, MM, KJ, JA, and JL contributed to the conception, study design.

MLS and JL contributed to the data analyses.

QZ, MO’H, CM, SB, MM, KJ, JA, MLS and JL contributed to the data interpretation, drafting and revising of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

None reported.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

The data source used for this study is comprised of administrative healthcare records that are deidentified and certified to be fully compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act patient confidentiality requirements. Institutional review board approval to conduct this study was not required because the study used only deidentified patient records and did not involve the collection, use, or transmittal of individually identifiable data.

Data availability statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

- Global Burden of Disease. 2015 Disease and injury incidence and prevalence collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388:1545–1602.

- SAMHSA.gov. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2019 national survey on drug use and health (HHS publication no. PEP20-07-01-001, NSDUH series H-55). Rockville (MD): Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2020.

- SAMHSA.gov. 2019 National survey on drug use and health (NSDUH): methodological summary and definitions substance abuse and mental health services administration. Rockville (MD): Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2020.

- Dold M, Bartova L, Fugger G, et al. Major depression and the degree of suicidality: results of the European Group for the Study of Resistant Depression (GSRD). Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018;21(6):539–549.

- Voelker J, Kuvadia H, Cai Q, et al. United States national trends in prevalence of major depressive episode and co-occurring suicidal ideation and treatment resistance among adults. J Affect Disord. 2021;5:100172.

- Citrome L, Jain R, Tung A, et al. Prevalence, treatment patterns, and stay characteristics associated with hospitalizations for major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2019;249:378–384.

- Ballou S, Mitsuhashi S, Sankin LS, et al. Emergency department visits for depression in the United States from 2006 to 2014. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2019;59:14–19.

- Owens PL, McDermott KW, Lipari RN, et al. Emergency department visits related to suicidal ideation or suicide attempt, 2008-2017: statistical brief #263. Healthcare cost and utilization project (HCUP). Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2020.

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383.

- Twenge JM, Cooper AB, Joiner TE, et al. Age, period, and cohort trends in mood disorder indicators and suicide-related outcomes in a nationally representative dataset, 2005-2017. J Abnorm Psychol. 2019;128(3):185–199.

- Neslusan C, Voelker J, Lingohr-Smith M, et al. Characteristics of hospital encounters and associated economic burden of patients with major depressive disorder and acute suicidal ideation or behavior. Hosp Pract. 2021;49(3):176–183.

- Cepeda MS, Schuemie M, Kern DM, et al. Frequency of rehospitalization after hospitalization for suicidal ideation or suicidal behavior in patients with depression. Psychiatry Res. 2020;285:112810.

- Hill T, Jiang Y, Friese CR, et al. Analysis of emergency department visits for all reasons by adults with depression in the United States. BMC Emerg Med. 2020;20(1):51.

- Beiser DG, Ward CE, Vu M, et al. Depression in emergency department patients and association with health care utilization. Acad Emerg Med. 2019;26(8):878–888.

- Zhdanava M, Kuvadia H, Joshi K, et al. Economic burden of treatment-resistant depression in privately insured U.S. patients with physical conditions. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2020;26:996–1007.

- Zhdanava M, Kuvadia H, Joshi K, et al. Economic burden of treatment-resistant depression in privately insured US patients with co-occurring anxiety disorder and/or substance use disorder. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(1):123–133.

- NCQA.org. Follow-up after hospitalization for mental illness (FUH). Washington (DC): National Committee for Quality Assurance; 2021.

- CMS.gov. Premier Hospital Quality Incentive Demonstration. Baltimore (MD): Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Updated 2020 Feb 11]. [cited 2021 Aug 5]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/HospitalPremier.

- Learn.premierinc.com. Premier Healthcare Database White Paper: Data that informs and performs. Charlotte (NC): Premier Applied Sciences®, Premier Inc. 2020. [cited 2021 Aug 5]. Available from: https://learn.premierinc.com/white-papers/premier-healthcaredatabase-whitepaper.

- Deb P, Norton EC. Modeling health care expenditures and use. Annu Rev Public Health. 2018;39:489–505.