Abstract

Objective

To provide a comprehensive evaluation of the economic burden associated with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) among children and adolescents from a US societal perspective.

Materials and methods

Direct healthcare costs of children (5–11 years) and adolescents (12–17 years) with ADHD were obtained using claims data from the IBM MarketScan Research Databases (01/01/2017–12/31/2018). Direct non-healthcare and indirect costs were estimated based on literature and government publications. Each cost component was estimated using a prevalence-based approach, with per-patient costs extrapolated to the national level.

Results

The total annual societal excess costs associated with ADHD were estimated at $19.4 billion among children ($6,799 per child) and $13.8 billion among adolescents ($8,349 per adolescent). Education costs contributed to approximately half of the total excess costs in both populations ($11.6 billion [59.9%] in children; $6.7 billion [48.8%] in adolescents). Other major contributors to the overall burden were direct healthcare costs ($5.0 billion [25.9%] in children; $4.0 billion [29.0%] in adolescents) and caregiving costs ($2.7 billion [14.1%] in children; $1.6 billion [11.5%] in adolescents).

Limitations

Cost estimates were calculated based on available literature and/or governmental publications due to the absence of a single data source for all costs associated with ADHD. Thus, the quality of cost estimates is limited by the accuracy of available data as well as the study populations and methodologies used by different studies.

Conclusion

ADHD in children and adolescents is associated with a substantial economic burden that is largely driven by education costs, followed by direct healthcare costs and caregiver costs. Improved intervention strategies and policies may reduce the clinical and economic burden of ADHD in these populations.

Introduction

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most common neurobehavioral disorders of childhood, characterized by levels of inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity that are inappropriate for the child’s developmental stageCitation1,Citation2. ADHD is most frequently diagnosed among grade-school children, but it may occur at any stage of lifeCitation3. The prevalence of ADHD among children and adolescents in the United States (US) is estimated at 10.0% and 6.5%, respectivelyCitation4,Citation5, compared with 4.4% among adultsCitation6.

ADHD symptoms vary depending on disease presentation and may be linked to reduced executive functioning, including loss of the ability to prioritize thoughts and actions as well as being forgetfulCitation2. Consequently, individuals with ADHD may display a multitude of functional and psychosocial impairments in the academic and/or occupational settingsCitation2,Citation7–9. While ADHD imposes a direct healthcare burden with regard to healthcare resource utilization (HRU), it also poses other challenges in children’s lives, such as educational difficultiesCitation7,Citation10–12. Additionally, the burden of ADHD borne by children and adolescents commonly extends to their caregiversCitation13–15. For instance, parents of children with ADHD may incur expenses for medical costs, special education, and/or require additional care services for their children, as well as the additional burden of indirect income loss due to missed workdays to provide additional care for their children. Given these additional expenses, it has been found that raising a child with ADHD to adolescence incurs five times higher economic burden compared to raising a child without ADHD, with the excess burden largely being driven by indirect income loss of caregivers due to missed workdays or losing their jobsCitation15. The burden may be particularly high for parents of children with ADHD who may also have the condition themselves. ADHD among parents may hinder their ability to tender their child’s needs, including their child’s ADHD management (e.g. ensuring treatment adherence, providing routines), due to their own difficulties with executive functioning. For these families, it may be especially important to also manage the parental ADHD to allow for optimal management of their child’s ADHD, given the important role that many parents play in the treatment of their childrenCitation16,Citation17.

Meanwhile, difficulties faced by children with ADHD are likely to continue into adolescence if their symptoms are not properly identified and well managed early onCitation18,Citation19. As adolescents with ADHD are generally faced with increasing academic, occupational, and social demands, further burdens of ADHD may be encountered, including higher risks of substance use and road traffic accidentsCitation2,Citation20–23. Furthermore, ADHD is known to be a chronic condition for some patients that can affect patients entire lifespanCitation24,Citation25, with 35%–78% of children and adolescents with ADHD maintaining symptoms through adulthoodCitation26,Citation27, and a recent report on the longitudinal remission patterns of ADHD in the Multimodal Treatment Study of ADHD (MTA) finding that 91% of children with ADHD continued to experience residual symptoms (i.e. only 9% of children with ADHD had sustained remission) into adulthoodCitation28. Thus, adolescents with ADHD are also at risk of experiencing a wide range of adverse outcomes associated with ADHD while transitioning to adulthood (e.g. increased unemployment, productivity loss)Citation29. The observation that a sizeable segment of childhood ADHD progresses into adulthood undoubtedly contributes to the large economic burden of ADHD in adults—a burden that exceeds that within children and adolescentsCitation11.

Given that the manifestation of ADHD among children and adolescents often has direct implications on how patients interact with society (e.g. with the education system or labor force), it is imperative to look beyond the patient and payer perspectives and consider the total societal costs associated with the condition to understand the true economic burden from a societal perspective. However, despite the extensive body of research conducted in children and adolescents with ADHD, the previous studies that sought to quantify the economic impact mostly have been from the payer perspective, assessing direct healthcare costs only, or have focused on a single or only a few components of ADHDCitation8,Citation30–33, without fully contextualizing the multifaceted nature of the disease burden. Previous literature has rarely attempted to monetize the burden comprehensively at a societal level across these multiple components (e.g. direct healthcare costs, education, caregiving, substance use, road traffic accidents, unemployment, productivity loss, premature mortality)Citation11,Citation34–36. Gupte-Singh et al. estimated that the annual total incremental cost of ADHD among patients aged 0–17 years was $3.92 billion in 2011. However, the only indirect cost component assessed was the costs of parents’ loss of productivity; other components that could be substantially costly in this patient population (e.g. costs of education) were not includedCitation34. A systematic review conducted by Doshi et al. found that the national annual incremental costs attributable to ADHD among children/adolescents in the US ranged from $32 to $72 billion; however, the study components were all derived from previously published literature dating back to 1999 and the study did not stratify cost components by the child and adolescent populationsCitation11. Notably, the burden associated with ADHD may differ between children and adolescents as the manifestation of the disease as well as one’s social role may change as patients develop throughout the life course, and hence it would be noteworthy to stratify results by child and adolescent populations to allow for the comparison of the relative importance of cost components using a common methodologyCitation11,Citation35,Citation36.

To build upon existing literature and highlight the various stakeholders involved in the economic burden of ADHD, this study aimed to provide a comprehensive evaluation of the economic burden of ADHD among children and adolescents, separately, in the US from a societal perspective. The research sought to identify the major cost components contributing to the societal economic burden associated with ADHD in children and adolescents, which may help drive new clinical (e.g. patient management) and social (e.g. education, disability) policies to mitigate the impact of ADHD on patients and society at large.

Methods

This study applied a prevalence-based approach, primarily with a bottom-up method, to estimate the excess costs incurred by an individual with ADHD compared to an individual without ADHD in the US in 2018. In this approach, the average per-patient excess costs were scaled up to the national level by multiplying the per-patient costs by the number of individuals with ADHD, estimated from the prevalence rate of ADHD and census population data. A top-down method was used for cost components in which data on the total costs associated with ADHD were available (e.g. research funding). Details of data sources and calculations are described below.

Data sources

Direct healthcare costs of children (aged 5–11 years) and adolescents (aged 12–17 years) with ADHD were obtained from health insurance claims data based on the IBM MarketScan Commercial and Medicaid Subsets from 01/01/2017 to 12/31/2018. Patients with ADHD were identified based on two diagnosis claims of ADHD (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] codes: 314.0x; International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM] codes: F90.x) on distinct dates. The index date was defined as the most recent calendar date that was followed by 12 months of continuous health plan coverage. The study period was defined as the 12-month period following the index date. The respective direct non-healthcare costs and indirect costs of children and adolescents with ADHD were estimated based on a review of academic literature and government agency publications. A targeted literature review was conducted to identify each of the potential cost inputs and the final decision for inclusion in the study was based on clinical input and discussion with experts to identify credible and accurate estimates that were relevant to the current study.

Estimation of ADHD prevalence

The prevalence of ADHD among children and adolescents in the US in 2018 was obtained from the US National Survey of Children's Health (NSCH)Citation4 and the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R), respectivelyCitation5,Citation37. The NSCH is a nationwide survey on the physical and emotional health of American children, including an indicator specific for ADHD. Households were randomly sampled across all US states and one child was randomly selected among each household to be the subject of the survey, which was completed by a parent or guardian who was familiar with the child’s health. Survey results were weighted to represent the population of non-institutionalized children in the USCitation4. The NCS-R estimated the number of adolescent residents with ADHD in US households based on a nationwide household survey of the prevalence and correlates of mental disorders plus the number of adolescent students sampled from a nationally representative sample of schools in the USCitation37. The total number of children and adolescents with ADHD was estimated, separately, by multiplying the prevalence rate and the total population of children and adolescents in the US in 2018 based on data from the US Census BureauCitation38.

Excess costs of ADHD among children and adolescents

The total excess all-cause costs incurred by children and adolescents with ADHD in the US in 2018 were calculated as the sum of the excess direct healthcare costs, the excess direct non-healthcare costs, and the excess indirect costs attributable to ADHD. Specifically, direct healthcare costs were defined as all amounts reimbursed by payers and patients' out-of-pocket costs observed in the claims database, as well as uncompensated healthcare costs covered by the federal, state, and local institutions as well as by the private sector for uninsured individuals. Direct non-healthcare costs were defined as costs identified in published academic and governmental literature that were actual expenses billed or paid, and indirect costs were defined as opportunity costs to society that were not directly observable. Excess costs associated with ADHD were estimated through a prevalence-based approach using the average cost differences between an individual with ADHD and an individual without ADHD or the general population (if data on individuals without ADHD was unavailable). The estimated prevalence rate from nationally representative surveys was then applied to extrapolate per-patient cost to a national level, using census population data, to derive a cost estimate for the total population for one year. Each cost component was estimated to be specific to children and adolescents (i.e. two mutually exclusive populations). Multiple data sources were leveraged to measure each cost component (), and each estimated cost component was weighted by the distribution of the relevant patient characteristics in the US population in 2018 (e.g. the proportion of individuals with each type of health plan coverage and the proportion without a health plan coverage [uninsured]). Given that some literature-derived parameters were collected before 2018, costs were inflated using the Consumer Price Index and population growth was accounted for using the growth factor relative to 2018, derived from population estimates.

Table 1. Summary of clinical findings and costs for each component of the total economic burden of ADHD in children and adolescents.

Sensitivity analyses were also conducted by varying the prevalence, excess total direct healthcare costs of an uninsured patient, discount rate, and proportion of patients with ADHD who seek treatmentCitation39,Citation40.

Estimation of direct healthcare costs

Direct healthcare costs for Medicaid or commercially insured children and adolescents were calculated as the sum of the primary payer's paid amount and patient out-of-pocket expenses. The costs comprised all-cause pharmacy costs and medical service costs, and the latter included outpatient (e.g. office visit, home care, ambulatory surgery center), inpatient, emergency room, and durable medical equipment costs. Patients were grouped based on their respective health plan coverage, and each group was divided into the ADHD cohort and the non-ADHD cohort based on recorded diagnoses of ADHD. Patients in the ADHD cohort were matched exactly to those in the non-ADHD cohort up to a 1:3 ratio based on characteristics including age, gender, region of residence, race, health plan, and year of the index date. The excess costs of insured patients with ADHD were expressed as the difference between the average all-cause costs incurred by patients with ADHD and those without ADHD over the 12-month study period, weighted by the ADHD population size in the respective plan type and apportioned to account for the proportion of patients who seek medical services in the ADHD population.

The excess direct healthcare costs of uninsured children and adolescents with ADHD were included in the weighted average calculation as uncompensated healthcare costs, which were based on a prior estimate in the literature for the overall US populationCitation41 and adjusted using data from the current Medicaid population to account for the higher excess costs of uninsured individuals with ADHD.

Estimation of direct non-healthcare costs

Direct non-healthcare costs associated with ADHD in children and adolescents included the following components: education, research, and training (i.e. funding allocated by the National Institute of Health [NIH]Citation42), substance use (adolescents only), and road traffic accidents (adolescents of driving age [aged 16–17 years] only).

Specifically, excess education costs were calculated as the excess number of days per year devoted to ADHD-related special education in children or adolescents with ADHD (i.e. 3.5 yearsCitation43) multiplied by the cost of one year of special educationCitation44; the excess number of days per year of grade retention in children or adolescents with ADHD (i.e. 0.3 yearsCitation43) multiplied by the cost of one year of regular education in the USCitation45; and the cost of one year of ADHD-related disciplinary events in children or adolescents with ADHDCitation43.

Research and training costs were calculated with the assumption that the proportion of funding allotted to the research on children/adolescents with ADHD (i.e. $58.0 million in 2018Citation42) was equal to the proportion of children/adolescents with ADHD in the overall ADHD population in the US.

Substance use costs were calculated as the excess number of adolescents with alcohol or drug abuse disorder due to ADHD (i.e. 5.4% with alcohol use disorder and 8.8%, with drug use disorderCitation22,Citation46) multiplied by the average cost of alcohol or drug abuse disorder in the US (i.e. costs to the criminal justice system, property and personal costs incurred by crime victims, costs associated with loss of productivity for incarcerated individuals, and prevention and research costs associated with alcohol use disorder and drug use disorder)Citation47–49.

Road traffic accident costs were calculated as the excess number of road traffic accidents due to ADHD (i.e. the total number of road traffic accidents in the US adolescent populationCitation50 and accounting for 27.0% higher risk of US adolescents with ADHD of driving age being involved in a road traffic accidentCitation21) multiplied by the average cost of a road traffic accident in the US (i.e. insurance, legal, congestion, and property damageCitation51).

Estimation of indirect costs

Excess indirect costs associated with ADHD in children and adolescents were estimated using a human capital approach in which costs were derived based on paid work compensation rates (i.e. an individual’s productivity was valued at their expected market earnings)Citation52. Cost components in this category included costs associated with caregiving, unemployment (adolescents of working age [aged 16–17 years] only), productivity loss at work (adolescents of working age [aged 16–17 years] only), and premature mortality (adolescents only).

Specifically, caregiving costs were calculated as the number of children or adolescents with ADHD multiplied by the estimated annual cost of ADHD-related caregiving per child or adolescent with ADHD (i.e. excess number of hours per year devoted to ADHD-related caregiving per individual with ADHD multiplied by the median hourly earnings of adults) in the US. Based on inputs from the literature, the costs associated with raising a child with ADHD over the course of the child's development include monetized direct costs related to the child's behavior (e.g. legal involvement, accident/injury, and damaged property) and indirect costs related to caregiver strain (e.g. income loss due to getting fired, changed responsibilities, or missing work, parental mental health services, and additional childcare)Citation15.

Given known differences in labor force participation and income by gender, cost estimates for unemployment and productivity loss were first stratified by gender, and the sum of the excess costs by gender was presented as an aggregate estimate.

Unemployment costs were calculated as the excess number of unemployed male or female adolescents with ADHD multiplied by the median annual earnings of male or female employees in the USCitation53–55. Based on the literature, adolescent males and females of working age with ADHD in the labor force are reported to be 2.1 times and 1.3 times more likely to be unemployed, respectively, compared with their respective counterparts without ADHDCitation29. The aggregated excess costs of unemployment were the sum of that of males and females.

The costs of productivity loss at work among adolescents were calculated as the excess number of days per year lost due to ADHD-related absenteeism (i.e. missed workdays) or presenteeism (i.e. low performance while physically at work) multiplied by the median daily earnings of male or female employees multiplied by the number of employed male or female adolescents with ADHD in the USCitation53–55. Based on inputs from the literature, the excess number of workdays lost per year due to ADHD-related absenteeism and presenteeism in the US is 13.6 and 21.6, respectivelyCitation56.

Premature mortality costs were calculated based on the number of excess all-cause deaths among adolescents with ADHD (i.e. 1.5 times higher than that among adolescents without ADHDCitation57,Citation58), average annual earnings, the employment to population ratio per age groupCitation54,Citation55, and a 3.0% discount rate to estimate the excess productivity loss from all-cause deaths.

Results

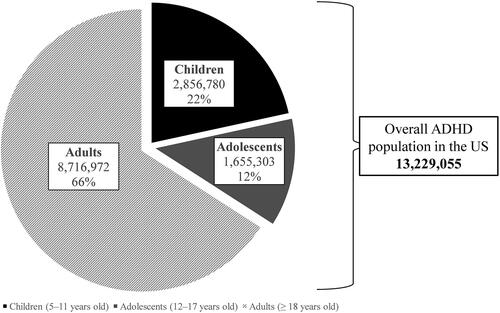

According to the most recent estimates at the time of study, the prevalence of ADHD among children (aged 5–11 years) and adolescents (aged 12–17 years) was 10.0% and 6.5%, respectivelyCitation4,Citation5, which corresponds to an estimated 2,856,780 children and 1,655,303 adolescents living with ADHD in the US. As shown in , ADHD in children and adolescents was estimated to comprise about one-third of the total ADHD prevalence in the US population after accounting for the respective population size of children, adolescents, and adults in the USCitation4–6,Citation38.

Figure 1. Overall ADHD population in the US in 2018. Abbreviations. ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; US, United States.

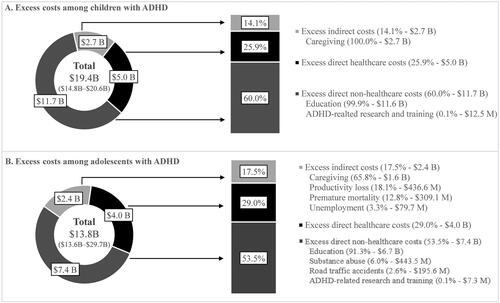

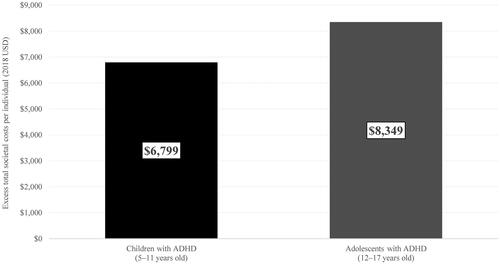

The total excess costs and the constituent cost components associated with ADHD in children and adolescents are summarized in and . Based on the prevalence estimates, the total societal excess costs associated with ADHD were estimated at $19.4 billion in children, or $6,799 per child with ADHD (), and $13.8 billion in adolescents, or $8,349 per adolescent with ADHD (). Based on the sensitivity analyses, the total excess costs ranged from $14.8 billion to $20.6 billion for children with ADHD (i.e. $5,166–$7,197 per child) and $13.6 billion to $29.7 billion for adolescents with ADHD (i.e. $8,191–$17,932 per adolescent).

Figure 2. Excess economic burden of ADHD in (A) child and (B) adolescent populations in 2018, USD. Abbreviations. ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; B, billion; M, million; US, United States; USD, United States dollar.

Figure 3. Excess economic burden per individual with ADHD in the US population in 2018, USD. Abbreviations. ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; US, United States; USD, United States dollar.

Direct healthcare costs

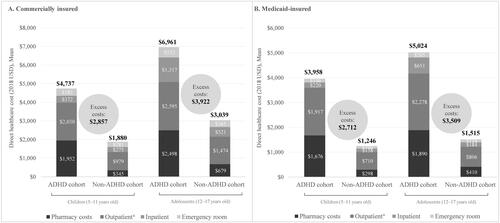

Among children in the US, the excess direct healthcare costs attributable to ADHD based on claims data were estimated at $2,801 per child with ADHD in 2018 (). The estimated costs were similar across children with different health plan types and ranged from $2,712 to $2,857 per child with ADHD (). The estimated costs were apportioned to the US child population with ADHD who received any form of healthcare services (estimated at 62.8%)Citation4, resulting in excess direct healthcare costs of $1,759 per child with ADHD. Hence, the total excess direct healthcare costs were estimated at $5.0 billion among children with ADHD in 2018, which accounted for 25.9% of the total societal excess costs associated with ADHD in children ().

Figure 4. Annual direct healthcare costs in (A) commercially insured and (B) Medicaid-insured children and adolescents with ADHD vs. without ADHD. Abbreviations. ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; USD, United States dollar. aOutpatient costs also include costs of durable medical equipment.

Among adolescents in the US, the excess direct healthcare costs attributable to ADHD based on claims data were estimated at $3,718 per adolescent with ADHD in 2018 (). When stratified by health plan type, the average excess direct healthcare costs associated with ADHD were found to be similar and ranged from $3,509 to $3,922 per adolescent with ADHD (). After apportioning the estimated costs to the US adolescent population with ADHD who received any form of healthcare services (estimated at 65.2%)Citation4, the excess direct healthcare costs were estimated at $2,424 per adolescent with ADHD. Hence, the total excess direct healthcare costs were estimated at $4.0 billion among adolescents with ADHD in 2018, which accounted for 29.0% of the total societal excess costs associated with ADHD in adolescents ().

Direct non-healthcare costs

Education

The total excess costs of education among children with ADHD were estimated at $11.6 billion in 2018. Overall, excess education costs accounted for 99.9% of the total excess non-healthcare costs and 59.9% of the total societal excess costs associated with ADHD among children in the US (; ). Among adolescents with ADHD, the total excess costs of education were estimated at $6.7 billion. Overall, excess education costs accounted for 91.3% of the total excess non-healthcare costs and 48.8% of the total societal excess costs associated with ADHD among adolescents in the US (; ).

Research and training

The excess research and training costs on ADHD incurred were estimated at $12.5 million for children and $7.3 million for adolescents with ADHD in 2018 ().

Substance use disorder

The excess costs of substance use disorders due to ADHD among adolescents in the US were estimated at $443.5 million ().

Road traffic accidents

The excess costs of road traffic accidents due to ADHD in the US adolescent population were estimated at $195.6 million ().

Indirect costs

Caregiving

The annual excess costs of caregiving incurred by raising a child with ADHD were estimated at $2.7 billion and costs incurred by raising an adolescent with ADHD were estimated at $1.6 billion. Overall, the excess costs of caregiving accounted for 14.1% and 11.5% of the total societal excess costs in children and adolescents with ADHD, respectively (; ).

Unemployment

The estimated combined excess costs of unemployment due to ADHD in the US adolescent population were $79.7 million ( ).

Productivity loss at work

The estimated excess costs of productivity loss at work due to ADHD in the US adolescent population were estimated at $436.6 million (; ).

Premature mortality

The excess costs of productivity loss due to premature mortality associated with ADHD in the US adolescent population were estimated at $309.1 million (; ).

Discussion

This comprehensive societal analysis of the excess economic burden of ADHD among children and adolescents found the total societal costs associated with ADHD in the US in 2018 to be ∼$19.4 billion among children and $13.8 billion among adolescents with ADHD. These findings demonstrate the substantial economic burden of ADHD in children and adolescents in the US and highlight the current unmet need in these populations. Specifically, costs due to education contributed to roughly half of the total burden of ADHD in both populations, which were estimated at $11.6 billion (59.9% of total excess costs) in children and $6.7 billion (48.8% of total excess costs) in adolescents. The main driver of education costs was the costs associated with special education, which, based on the literature inputs, constituted an additional 97 days per year spent on education for children and adolescents with ADHDCitation43 and could be associated with costs attributable to tutoring, employing special education teachers/service providers/administrators, and spending on non-personnel items (e.g. materials, supplies, technological supports)Citation44. Other major contributors to the overall burden of ADHD among children and adolescents were direct healthcare costs ($5.0 billion in children [25.9%]; $4.0 billion in adolescents [29.0%]) and caregiving costs ($2.7 billion in children [14.1%]; $1.6 billion in adolescents [11.5%]). The excess costs in children and adolescents were estimated to constitute about one-fifth of the total societal excess costs associated with ADHD in the US population, with an additional $122.8 billion being attributable to the adult population with ADHDCitation59. Overall, ADHD was associated with a substantial economic burden, which appeared to be higher than anxiety and depression on a population levelCitation59–65. The observation that a large proportion of the total economic burden of ADHD among children and adolescents is attributable to education costs, a direct non-healthcare cost, distinguishes it from many other medical conditions, where costs are largely associated with direct medical costs (e.g. hospitalizations). Additionally, the observed relative importance of direct non-healthcare costs in children and adolescents differs from previous findings among adults with ADHD, in which the largest cost drivers reported were indirect costs (e.g. productivity loss)Citation59. The significant costs of education associated with ADHD align with the findings of a recent systematic literature review on the economic impact on the education sector of various mental and neurodevelopmental disorders (e.g. ADHD, anxiety, depression, autism)Citation66. The review highlights that ADHD is among the top conditions associated with the highest proportion of education costs, only behind intellectual disability disorder and autism. These latter conditions, as with ADHD, often have a direct impact on one’s ability to learn and develop at school, resulting in costs due to various events, such as tutoring, repeating a grade, the need and purchase of educational technological devices, and counseling servicesCitation44.

The key cost components contributing to the total societal excess costs associated with ADHD in children and adolescents in the US identified in the current analysis are consistent with previous findings reported by Doshi and colleaguesCitation11. Both analyses demonstrate that the costs associated with education, direct healthcare, and caregiving are the major drivers of societal excess costs associated with ADHD in children and adolescents in the US. The relative importance of the cost components differs between the analyses, likely due to the use of different methodologies for the estimation of direct healthcare costs. The Doshi et al. study utilized cost inputs from multiple studies with different settings and patient identification criteria, and the data of which were mostly collected in the 1990s. By comparison, direct healthcare costs in the current study were estimated based on adjusted real-world costs captured by the claims database during the 12-month study period between 2017 and 2018. The exclusive use of a more recent claims database for direct healthcare cost estimates in the current analysis allows for a comparison between patients with ADHD and a matched cohort group, which provides a contemporary and accurate estimation of the added burden of ADHD among insured individuals. Additionally, it allows for a precise stratification of costs by age groups, which provides a comprehensive view of the cost breakdowns among the child and adolescent populations.

The largest excess cost component attributable to ADHD among children and adolescents identified in the current analysis was the costs associated with education, which is the major activity engaged in by these populations. Children and adolescents with ADHD often exhibit impaired cognitive skills and psychosocial functioning that lead to poor academic outcomesCitation30,Citation67. The excess education costs were mainly driven by special education, such as tutoring and counseling servicesCitation43. A survey showed that children with a parent-reported diagnosis of ADHD were five times more likely to receive special education servicesCitation68 compared with those without a reported diagnosis; this adds significant monetary costs to the education system and puts extra strain on education staffCitation43,Citation44,Citation69. Additionally, due to the age and general lack of independence of children and adolescents, the impact of ADHD on academic outcomes may also be associated with a burden borne by families or caregivers who may bear the direct monetary costs and may also incur indirect costs from their own occupational and socio-emotional consequences, such as job loss, missed leisure activities, and need for mental health supportCitation15.

Currently available treatments for children and adolescents with ADHD are associated with improvements in certain academic and emotional outcomesCitation30,Citation70–72. However, despite the various pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic treatments available, barriers to treatment uptake exist as many children and adolescents with ADHD remain undiagnosed or untreatedCitation19,Citation25. Indeed, a study based on the 2016 NSCH revealed that among US children and adolescents aged 2–17 years with parent-reported ADHD, ∼23% have never received pharmacologic or non-pharmacologic treatmentsCitation39; and among those who do initiate treatment, adherence and persistence tend to be poorCitation73–76. Evidence suggests that adherence and persistence to stimulant medication among children and adolescents with ADHD are relatively low in both clinical trials and real-world settings, and tend to decrease over timeCitation74,Citation75, with treatment discontinuation rates found to be around 20% within the first 12 months of treatment and increasing to 40% after 24 months in a medical record–based longitudinal cohort studyCitation77. The reasoning for poor treatment uptake and low adherence and persistence is likely multifaceted and may differ depending on the patient’s life stage. For instance, parents may be reluctant for their young children to use medication even though most research evidence suggests a strong immediate effect of medication on alleviating ADHD core symptomsCitation25,Citation78. In addition, children who do initiate ADHD medication may have poor adherence due to difficulties swallowing the medication or inadequate monitoring by parentsCitation76, while poor adherence in adolescents may be more likely due to social peer pressure and greater autonomy in their own decision-makingCitation75. Poor adherence may also be partly attributable to the symptoms of ADHD that impair executive functioning and render the patients forgetting to take medications, which can be increasingly problematic in adolescents who may prefer to manage their own treatment schedulesCitation2. Meanwhile, adverse effects of medication, which may include insomnia and appetite lossCitation79, are one of the most common reasons for discontinuationCitation76. Other reasons for poor adherence and persistence in these populations may include dosing inconveniences and suboptimal response of existing treatments, parents’ decisions to discontinue treatment, delays in prescription fills (e.g. due to regulations of controlled substances such as stimulants that lead to shortages in pharmacies), and social stigma to ADHD medicationsCitation75,Citation76,Citation80,Citation81. Collectively, low rates of treatment uptake, combined with low rates of adherence and persistence, may limit the potential management of ADHD-related symptoms, and ultimately lessen the beneficial impact of treatment on reducing the burden of ADHD in these populations. The current unmet need among patients with ADHD highlights the importance of developing improved treatments with simpler dosing schedules and improved tolerability profiles that may help increase rates of adherence and persistence. Additionally, shedding light on the reasons behind ADHD treatment barriers, such as reasons for treatment changes, may help clinicians tailor treatment management strategies to patients with ADHD in various life stages, which may improve the quality of care and lead to better clinical outcomes.

The substantial burden of ADHD in children and adolescents observed in the current study suggests that additional efforts are needed to address the unmet needs in these populations, and the stratified results for each cost component may inform policy decision-makers on key focus areas. For instance, educational difficulties (e.g. poor academic outcomes)Citation7 and other school-related issues (e.g. conduct and social problems), which may be exacerbated by unmanaged ADHD symptoms, such as hyperactivity and inattentionCitation18,Citation19,Citation82, and comorbid conditions, such as oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and conduct disorder (CD)Citation2, are the major burdens faced by children and adolescents with ADHD. In this regard, along with developing improved treatment strategies, school policies that encourage classroom accommodations, and increased collaboration among school professionals to tailor management for individual students with ADHD may help alleviate certain academic and social challengesCitation31,Citation83. For instance, it has been shown that collaborative consultation between the school psychologist and classroom teachers as well as consultations including the family of children with ADHD may result in improved academic metrics (e.g. reading/math skills, homework performance) for these childrenCitation84,Citation85. Meanwhile, a recent review on prospective follow-up studies of children with ADHD found that the high rates of persistence of ADHD symptoms among children may result in downstream negative outcomes in adulthood, including impacts on education, occupation, and social, physical, and mental health; therefore, early educational interventions that address conduct and behavioral issues of children and adolescents with ADHD may have long term benefits and improve outcomes in adulthoodCitation86.

Additionally, it has been suggested that access to disability services, including accommodation programs and continued care, is becoming increasingly challenging for an individual with ADHD as they age (e.g. for adolescents and young adults). Typically, a formal diagnosis and documents that demonstrate that the individual's ADHD symptoms result in substantial impairment of functioning compared to the general population are required to deem the patient eligible for disability services. However, diagnosing ADHD and determining the level of functioning of adolescents and adults may be more difficult than for children as the diagnostic criteria for ADHD symptoms in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders are child-centric, highlighting the importance of inclusive diagnostic scales to aid clinicians in diagnosing ADHD across the life course. Ensuring that clinicians are well equipped to identify and diagnose ADHD among older patients, increasing awareness of requirements stipulated by disability service providers, and subsidizing these types of required assessments may help to improve access to important services for patients with ADHDCitation75,Citation87,Citation88.

In addition, raising public awareness of ADHD may help reduce social stigma and lessen the peer pressure faced by children and adolescents with ADHD, which may in turn increase medication adherence and persistence and hence treatment effectiveness. Improved public education on the condition may also allow employers to be more understanding towards employees with family members who have ADHD, which may lead to higher job stability and better career prospects among these employees, thereby mitigating some of the caregiver burdens. Empathy from employers may also alleviate the burden of adolescents or young adults entering the workforce. Additionally, as ADHD may be a chronic condition for some patients, with symptoms persisting into adulthoodCitation26,Citation27, better management of symptoms in children and adolescents may also help alleviate the long-term burden by placing them in a more favorable position as they transition into adulthood (e.g. educational achievement, employment opportunity)Citation11,Citation89. Taken together, the development of improved intervention strategies as well as policies and awareness around ADHD are needed to overcome treatment barriers, improve adherence and persistence, alleviate educational difficulties, and minimize stigmatization, which has the potential to improve various aspects of the patient’s life across life stages and reduce the economic burden from a societal perspective.

The findings of this study should be interpreted in light of certain limitations. Costs were estimated using a prevalence-based approach to capture the economic burden of ADHD in a given year for a representative population of children and adolescents with ADHD. As such, the total economic burden of ADHD per individual should be interpreted as the potential cost savings if ADHD were to be removed from society, and thus should not be interpreted as the potential cost savings from averting a case of ADHD (i.e. if an incident-based approach were to have been applied) or curing a case of ADHD at a given point in their disease trajectory (i.e. accounting for lifetime ADHD effects on human capital formation). The excess direct healthcare costs for insured individuals were estimated based on data from a claims database, which includes diagnosis information collected for administration purposes and may not fully reflect all direct healthcare costs incurred by patients with ADHD. Additionally, as patients were identified based on documented diagnoses of ADHD, individuals with undiagnosed ADHD were not captured, which may lead to an under-estimation of the total excess direct healthcare costs attributable to ADHD in the population. For the estimation of excess direct healthcare costs for those who are uninsured with ADHD, as well as excess direct non-healthcare costs and indirect costs, the estimates were calculated based on available literature and/or governmental publications due to the absence of a single data source for all costs associated with ADHD. As such, the point estimates provided had inherent uncertainty with variation based on each input. Furthermore, the quality of cost estimates is limited by the accuracy of available data as well as the study populations and methodologies used by different studies and may not always be generalizable to the entire population of patients with ADHD. Nonetheless, sensitivity analyses based on several variables were conducted to provide the lower and upper bound estimates for the total excess costs in each studied population. Lastly, cost components were set to be mutually exclusive to avoid overlapping of cost-counting across categories, which may lead to the true burden of a given cost component being under- or over-estimated if an associated cost had already been covered in another category. For example, to keep cost components mutually exclusive, the costs of road traffic accidents (for the adolescent population) included only property damage costs and not medical costs, because medical costs associated with road traffic accidents were captured as direct healthcare costs. Therefore, the estimated costs associated with road traffic accidents were likely an under-estimation.

Conclusion

Childhood ADHD is associated with numerous negative outcomes, such as poor academic performance, increased healthcare costs, and caregiver burdens. The impact of ADHD may lead to further negative consequences among children and adolescents with ADHD, such as challenges with social relationships and low self-esteem. Given that childhood ADHD often persists into adulthood, these negative outcomes may continue and manifest in similar ways, such as poor performance at work and difficulties with social relationships. The current findings demonstrate that the economic burden of ADHD among children and adolescents in the US is substantial and mainly driven by education costs. Despite available treatment options, an important unmet need remains. Thus, the development of more effective, safe, convenient, and accessible intervention strategies and accompanying policies may reduce the clinical and economic burden of ADHD in children and adolescents. At the same time, improved management of ADHD symptoms in these patients may also help alleviate the long-term implications of ADHD and ultimately reduce the economic burden across the life course.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. The study sponsor contributed to and approved the study design, participated in the interpretation of data, and reviewed and approved the manuscript; all authors contributed to the development of the manuscript and maintained control over the final content.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

JS is an employee of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc.

LAA received research support from Shire/Takeda, Sunovion, and Otsuka; received consulting fees from Bracket, Shire/Takeda, Sunovion, Otsuka, State University of New York (SUNY), the National Football League (NFL), and Major League Baseball (MLB); and received royalty payments (as inventor) from New York University (NYU) for license of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) scales and training materials.

AC received research support from Allergan, Takeda/Shire, Emalex, Akili, Ironshore, Arbor, Aevi Genomic Medicine, Neos Therapeutics, Otsuka, Pfizer, Purdue, Rhodes, Sunovion, Tris, KemPharm, Supernus, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration; was on the advisory board of Takeda/Shire, Akili, Arbor, Cingulate, Ironshore, Neos Therapeutics, Otsuka, Pfizer, Purdue, Adlon, Rhodes, Sunovion, Tris, Supernus, and Corium; received consulting fees from Arbor, Ironshore, Neos Therapeutics, Purdue, Rhodes, Sunovion, Tris, KemPharm, Supernus, Corium, Jazz, Tulex Pharma, and Lumos Pharma; received speaker fees from Takeda/Shire, Arbor, Ironshore, Neos Therapeutics, Pfizer, Tris, and Supernus; and received writing support from Takeda/Shire, Arbor, Ironshore, Neos Therapeutics, Pfizer, Purdue, Rhodes, Sunovion, and Tris.

PGS, MD, FK, MC, AG, and PL are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc., which funded the development and conduct of this study and manuscript.

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

JS, LAA, AC, PGS, MD, FK, MC, AG, and PL contributed to the design of the study and interpretation of the data. PGS, MD, FK, MC, AG, and PL contributed to the data collection and data analysis. All authors critically revised the draft manuscript and approved the final content.

Previous presentation

Part of the material in this manuscript was presented at the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) 2021 Virtual Meeting from May 17 to 20 as a podium presentation.

Acknowledgements

Medical writing assistance was provided by Flora Chik, an employee of Analysis Group, Inc.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): U.S. Department of Health & Human Services; 2021 [cited 2021 Jun 24]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/facts.html

- Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (CHADD). About ADHD; 2017. p. 1–6.

- American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. ADHD Parents Medication Guide; 2013. p. 1–45.

- Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. 2018 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) data query. Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health supported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB) [cited 2020 Feb 26]. Available from: www.childhealthdata.org.

- Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ, et al. Prevalence, persistence, and sociodemographic correlates of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(4):372–380.

- Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):716–723.

- DuPaul GJ, Langberg JM. Educational impairments in children with ADHD. In: Barkley RA, editor. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a handbook for diagnosis and treatment. New York: The Guilford Press; 2015. p. 169–190.

- Kuriyan AB, Pelham WE, Jr., Molina BS, et al. Young adult educational and vocational outcomes of children diagnosed with ADHD. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2013;41(1):27–41.

- Shaw M, Hodgkins P, Caci H, et al. A systematic review and analysis of long-term outcomes in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: effects of treatment and non-treatment. BMC Med. 2012;10:99.

- Chan E, Zhan C, Homer CJ. Health care use and costs for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: national estimates from the medical expenditure panel survey. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(5):504–511.

- Doshi JA, Hodgkins P, Kahle J, et al. Economic impact of childhood and adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the United States. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(10):990–1002 e2.

- Hakkaart-van Roijen L, Zwirs BW, Bouwmans C, et al. Societal costs and quality of life of children suffering from attention deficient hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;16(5):316–326.

- Fridman M, Banaschewski T, Sikirica V, et al. Factors associated with caregiver burden among pharmacotherapy-treated children/adolescents with ADHD in the caregiver perspective on pediatric ADHD survey in Europe. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:373–386.

- Kleinman NL, Durkin M, Melkonian A, et al. Incremental employee health benefit costs, absence days, and turnover among employees with ADHD and among employees with children with ADHD. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51(11):1247–1255.

- Zhao X, Page TF, Altszuler AR, et al. Family burden of raising a child with ADHD. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2019;47(8):1327–1338.

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Wang CH, Woods KE, et al. Parent ADHD and evidence-based treatment for their children: review and directions for future research. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2017;45(3):501–517.

- Waxmonsky JG, Waschbusch DA, Babinski DE, et al. Does pharmacological treatment of ADHD in adults enhance parenting performance? Results of a double-blind randomized trial. CNS Drugs. 2014;28(7):665–677.

- Madsen KB, Ravn MH, Arnfred J, et al. Characteristics of undiagnosed children with parent-reported ADHD behaviour. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;27(2):149–158.

- Okumura Y, Yamasaki S, Ando S, et al. Psychosocial burden of undiagnosed persistent ADHD symptoms in 12-year-old children: a population-based birth cohort study. J Atten Disord. 2021;25(5):636–645.

- Charach A, Yeung E, Climans T, et al. Childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and future substance use disorders: comparative Meta-analyses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(1):9–21.

- Curry AE, Yerys BE, Metzger KB, et al. Traffic crashes, violations, and suspensions among young drivers with ADHD. Pediatrics. 2019;143(6):e20182305.

- Molina BS, Pelham WE. Jr. Childhood predictors of adolescent substance use in a longitudinal study of children with ADHD. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112(3):497–507.

- Thompson AL, Molina BS, Pelham W Jr, et al. Risky driving in adolescents and young adults with childhood ADHD. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32(7):745–759.

- Sciberras E, Streatfeild J, Ceccato T, et al. Social and economic costs of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder across the lifespan. J Atten Disord. 2022;26(1):72–87.

- Wolraich ML, Hagan JF Jr., Allan C, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2019;144(4):e20192528.

- Biederman J, Petty CR, Evans M, et al. How persistent is ADHD? A controlled 10-year follow-up study of boys with ADHD. Psychiatry Res. 2010;177(3):299–304.

- Kessler R, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602.

- Sibley MH, Arnold LE, Swanson JM, et al. Variable patterns of remission from ADHD in the multimodal treatment study of ADHD. Am J Psychiatry. 2021. DOI:10.1176/appi.ajp.2021.21010032

- Biederman J, Faraone SV. The effects of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder on employment and household income. MedGenMed. 2006;8(3):12.

- Arnold LE, Hodgkins P, Kahle J, et al. Long-term outcomes of ADHD: academic achievement and performance. J Atten Disord. 2020;24(1):73–85.

- DuPaul GJ, Kern L, Gormley MJ, et al. Early intervention for young children with ADHD: academic outcomes for responders to behavioral treatment. School Mental Health. 2011;3(3):117–126.

- Loe IM, Feldman HM. Academic and educational outcomes of children with ADHD. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32(6):643–654.

- Polderman TJ, Boomsma DI, Bartels M, et al. A systematic review of prospective studies on attention problems and academic achievement. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;122(4):271–284.

- Gupte-Singh K, Singh RR, Lawson KA. Economic burden of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among pediatric patients in the United States. Value Health. 2017;20(4):602–609.

- Matza LS, Paramore C, Prasad M. A review of the economic burden of ADHD. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2005;3:5.

- Pelham WE, Foster EM, Robb JA. The economic impact of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Ambul Pediatr. 2007;7(1 Suppl):121–131.

- Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ, et al. Design and field procedures in the US national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement (NCS-A). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2009;18(2):69–83.

- United States Census Bureau. 2018 American Community Survey; 2019.

- Danielson ML, Bitsko RH, Ghandour RM, et al. Prevalence of parent-reported ADHD diagnosis and associated treatment among U.S. children and adolescents, 2016. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2018;47(2):199–212.

- Xu G, Strathearn L, Liu B, et al. Twenty-year trends in diagnosed attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among US children and adolescents, 1997-2016. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(4):e181471.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Mean expenditure per person with expense by insurance coverage, United States, 2017. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey; 2017.

- United States Department of Health & Human Services. Estimates of funding for various research, condition, and disease categories (RCDC). Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools; 2019.

- Robb JA, Sibley MH, Pelham WE Jr., et al. The estimated annual cost of ADHD to the U.S. education system. School Ment Health. 2011;3(3):169–177.

- Chambers JG, Parrish TB, Harr JJ. What are we spending on special education services in the United States, 1999–2000? Report. Special; 2002.

- United States Census Bureau. Public elementary-secondary education finance data: per pupil amounts for current spending of public elementary-secondary school systems by state. Fiscal Year. 2017;2017.

- Molina BS, Pelham WE, Gnagy EM, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder risk for heavy drinking and alcohol use disorder is age specific. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(4):643–654.

- Sacks JJ, Gonzales KR, Bouchery EE, et al. 2010 National and state costs of excessive alcohol consumption. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(5):e73–e79.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Results from the 2018 national survey on drug use and health: detailed tables. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, National Survey on Drug Use and Health; 2019.

- US Department of Justice National Drug Intelligence Center. The economic impact of illicit drug use on American Society; 2011.

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Police-reported motor vehicle crashes in 2018, traffic safety facts; 2019.

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. The economic and societal impact of motor vehicle crashes, 2010 (Revised); 2015.

- Robinson R. Cost-benefit analysis. BMJ. 1993;307(6909):924–926.

- Ramtekkar UP, Reiersen AM, Todorov AA, et al. Sex and age differences in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms and diagnoses: implications for DSM-V and ICD-11. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(3):217–228 e1–3.

- United States Census Bureau. Employment status of the civilian noninstitutional population by age, sex, and race [cited 2020 Feb 27]. Available from: https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=unemployment&hidePreview=false&tid=ACSST1Y2018.S2301&vintage=2018

- United States Census Bureau. Work experience-people 15 years old and over, by total money earnings, age, race, hispanic origin, sex, and disability status; 2018.

- Kessler RC, Adler L, Ames M, et al. The prevalence and effects of adult attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder on work performance in a nationally representative sample of workers. J Occup Environ Med. 2005;47(6):565–572.

- Dalsgaard S, Ostergaard SD, Leckman JF, et al. Mortality in children, adolescents, and adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a nationwide cohort study. Lancet. 2015;385(9983):2190–2196.

- Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu J, et al. Deaths: final data for 2017: national vital statistics reports, US Department of Health & Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, USA; 2019 [cited 2019 Oct 14]. Available from: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/79486

- Adler LA, Childress A, Cloutier M, et al. Economic burden of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) among children and adolescents in the United States (US): a societal perspective. Value in Health. 2021;24(1):S6–S7.

- American Heart Association. Cardiovascular disease: a costly burden for America projections through 2035; 2017.

- Cloutier M, Aigbogun MS, Guerin A, et al. The economic burden of schizophrenia in the United States in 2013. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(6):764–771.

- Cloutier M, Greene M, Guerin A, et al. The economic burden of bipolar I disorder in the United States in 2015. J Affect Disord. 2018;226:45–51.

- Davis LL, Schein J, Cloutier M, et al. The economic burden of post-traumatic stress disorder in the United States from a societal perspective. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2021;27(4-a Suppl):S61.

- DuPont RL, Rice DP, Miller LS, et al. Economic costs of anxiety disorders. Anxiety. 1996;2(4):167–172.

- Greenberg PE, Stiglin LE, Finkelstein SN, et al. The economic burden of depression in 1990. J Clin Psychiatry. 1993;54(11):405–418.

- Pokhilenko I, Janssen LMM, Evers S, et al. Do costs in the education sector matter? A systematic literature review of the economic impact of psychosocial problems on the education sector. Pharmacoeconomics. 2021;39(8):889–900.

- Klassen AF, Miller A, Fine S. Health-related quality of life in children and adolescents who have a diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):e541–e547.

- LeFever GB, Villers MS, Morrow AL, et al. Parental perceptions of adverse educational outcomes among children diagnosed and treated for ADHD: a call for improved school/provider collaboration. Psychol Schs. 2002;39(1):63–71.

- Jones DE, Foster EM, Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Service use patterns for adolescents with ADHD and comorbid conduct disorder. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2009;36(4):436–449.

- Barbaresi WJ, Katusic SK, Colligan RC, et al. Modifiers of long-term school outcomes for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: does treatment with stimulant medication make a difference? Results from a population-based study. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2007;28(4):274–287.

- Rapport MD, Denney C, DuPaul GJ, et al. Attention deficit disorder and methylphenidate: normalization rates, clinical effectiveness, and response prediction in 76 children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33(6):882–893.

- Suzer Gamli I, Tahiroglu AY. Six months methylphenidate treatment improves emotion dysregulation in adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a prospective study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;14:1329–1337.

- Biederman J, Fried R, DiSalvo M, et al. Evidence of low adherence to stimulant medication among children and youths with ADHD: an electronic health records study. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(10):874–880.

- Charach A, Ickowicz A, Schachar R. Stimulant treatment over five years: adherence, effectiveness, and adverse effects. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(5):559–567.

- Wong IC, Asherson P, Bilbow A, et al. Cessation of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder drugs in the young (CADDY)–a pharmacoepidemiological and qualitative study. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13(50):iii–iv, ix–xi, 1–120.

- Gajria K, Lu M, Sikirica V, et al. Adherence, persistence, and medication discontinuation in patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder – a systematic literature review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014;10:1543–1569.

- Beau-Lejdstrom R, Douglas I, Evans SJ, et al. Latest trends in ADHD drug prescribing patterns in children in the UK: prevalence, incidence and persistence. BMJ Open. 2016;6(6):e010508.

- Faraone SV, Antshel KM. Towards an evidence-based taxonomy of nonpharmacologic treatments for ADHD. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2014;23(4):965–972.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Medicaid Program Integrity Education (MPIE). Stimulant and related medications: use in pediatric patients. 2015; p. 1–12.

- Adler LD, Nierenberg AA. Review of medication adherence in children and adults with ADHD. Postgrad Med. 2010;122(1):184–191.

- US Government Accountability Office (GAO). Drug shortages: Better management of the quota process for controlled substances needed; coordination between DEA and FDA should be improved. Washington, DC. 2015; p. 1–78.

- Wehmeier PM, Schacht A, Barkley RA. Social and emotional impairment in children and adolescents with ADHD and the impact on quality of life. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(3):209–217.

- Murray DW, Molina BS, Glew K, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of school services for high school students with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. School Ment Health. 2014;6(4):264–278.

- DuPaul GJ, Jitendra AK, Volpe RJ, et al. Consultation-based academic interventions for children with ADHD: effects on reading and mathematics achievement. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2006;34(5):635–648.

- Morris SH, Nahmias A, Nissley-Tsiopinis J, et al. Research to practice: implementation of family school success for parents of children with ADHD. Cogn Behav Pract. 2019;26(3):535–546.

- Cherkasova MV, Roy A, Molina BSG, et al. Review: Adult outcome as seen through controlled prospective follow-up studies of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder followed into adulthood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021. DOI:10.1016/j.jaac.2021.05.019

- Harrison AG, Rosenblum Y. ADHD documentation for students requesting accommodations at the postsecondary level: update on standards and diagnostic concerns. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56(8):761–765.

- Wilens TE, Spencer TJ. Understanding attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder from childhood to adulthood. Postgrad Med. 2010;122(5):97–109.

- Fletcher JM. The effects of childhood ADHD on adult labor market outcomes. Health Econ. 2014;23(2):159–181.

- United States Census Bureau. Enrollment status of the population 3 years and over, by sex, age, race, hispanic origin, foreign born, and foreign-born parentage; 2018 [cited 2020 Apr 29]. Available from: www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps.html