Abstract

Background

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is one of the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States and can lead to cervical, vulvovaginal, anal, penile, and oropharyngeal cancers. Compared with the general population, US military members are at a higher risk of HPV-related conditions, yet vaccination rates are relatively low in this population. As many service members may not be diagnosed with HPV-related cancers until after they leave active service, the objective of this study was to determine the incidence, prevalence, and economic burden of HPV-related cancers among US veterans.

Methods

The study used the 2014–2018 Veterans Health Administration (VHA) database to identify newly diagnosed adult patients (cases) with HPV-related cancers, including cervical, vulvovaginal, anal, penile, and oropharyngeal cancers. Cases were matched by age, race, and sex to patients without HPV related cancer (controls). Outcome measures included annual incidence, prevalence, health care resource utilization (HCRU), and costs. These outcomes were calculated from the index date (first cancer diagnosis) through the earliest of 24 months, death, or end of study period. Adjusted results were examined using generalized linear models.

Results

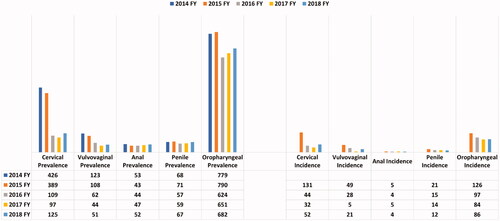

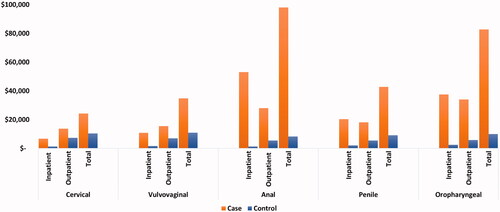

The annual prevalence and incidence rates of HPV-related cancers ranged from 43 (anal) to 790 (oropharyngeal) cases per million (CPM), and four (anal) to 131 (cervical) CPM, respectively. Compared with controls, cases had significantly higher annual HCRU. Mean numbers of annual inpatient hospitalizations were several times higher compared to controls (cervical: 6.7-times (×); vulvovaginal: 2.7×; penile: 6.6×; oropharyngeal: 10.2×; and anal: 14.9×; all p < 0.01). Similarly, cases had significantly higher all-cause healthcare costs vs. matched controls across all cancer types: cervical ($24,252 vs. $10,402), vulvovaginal ($34,801 vs. $10,913), penile ($42,772 vs. $9,139), oropharyngeal ($82,763 vs. $10,017), and anal ($98,146 vs. $8,339); (all p < 0.01).

Conclusions

HPV-related cancers may cause significant clinical and economic burden within the VHA system. Given the consequences of HPV-related cancers among veterans who did not have access to the vaccine, HPV vaccination of active military and eligible veterans should be considered a healthcare priority.

Introduction

As the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States (US), approximately 42.5 million people are infected with human papillomavirus (HPV), and 13 million become newly infected each yearCitation1–3. More than 43% of adults aged 18–59 years in the US are infected with genital HPV, with slightly higher rates of HPV infection in men (45%) compared to women (40%).

HPV can cause several diseases, such as genital warts, and result in cancers, including cervical, vulvar, vaginal, anal, penile, and head and neck cancersCitation1,Citation3–5. Consistent with a rising incidence and prevalence of HPV infection, HPV-related cancers also increased from 30,000 in 1999 to 43,000 in 20152. Prior studies have shown that approximately 90% of cervical and anal, 80% of oropharyngeal, 70% of vaginal and vulvar, and over 60% of penile cancers are attributable to an HPV infectionCitation6–8. More recently, HPV-related cervical and vaginal cancer rates decreased, presumably due to better screening practices and improved vaccination in women, while HPV-related oropharyngeal and anal cancer rates have increasedCitation2,Citation9–11. Over 80% of men with an HPV-related cancer had oropharyngeal cancer – with white men, aged 65–69 years, having the highest incidence of oropharyngeal cancer, at 41.6/100,000Citation10. Consistent with overall trends of HPV-related cancers among women and men in the general US population, a Department of Defense (DoD) repository study found a higher rate of HPV-related cancers among older males, defined as having ≥10 years of military serviceCitation11–13.

Considerable clinical and economic burden is associated with the healthcare costs of HPV-related cancers in the US populationCitation14–16. Resulting from multiple causes, delays in diagnosis and therapy may impact quality-of-life and prognosis, which can lead to increased healthcare costsCitation13,Citation17–21. The total annual medical care cost estimates for HPV-related cancers ranged from $52,700 to $146,100 (2018 US dollars) in the civilian populationCitation14. Over the past 10 years, HPV-related cancer costs have increased significantly and are projected to continue to rise as the prevalence increases and the standard of care is enhancedCitation14–16.

Since the introduction of the HPV vaccine, there has been an 88% decline in the prevalence of 4vHPV infection among women aged 14–19 years and an 81% decline among women aged 20–24 yearsCitation2. From 2013 to 2018, the HPV vaccination rate among adults aged 18–26 years increased from 22.1% to 39.9%. For women, the HPV vaccination rates increased from 36.8% (2013) to 53.6% (2018); over this timeframe, HPV vaccination tripled among men, from 7.7% to 27.0%Citation22. In contrast, the overall vaccination rates for men and women veterans were 11% and 38%, respectivelyCitation23–25.

Among male veterans of 18–26 years of age, evaluated between 2011 and 2017, only 1% had received their first dose of HPV vaccine prior to military service. With significant differences in age, marital status, education, and income between civilians and veterans, more civilians completed the three-dose HPV vaccination series compared to veteransCitation26.

To date, the literature has primarily focused on the clinical and economic burden of HPV-related cancers within the US civilian populationCitation1,Citation12,Citation27–29. There are limited data available addressing the epidemiological and economic consequences of HPV-related cancers in the US veteran population. To address this gap, the annual incidence and prevalence, as well as the health care resource utilization (HCRU) and cost outcomes, were examined in this study of VHA patients who were recently diagnosed with cervical, vulvovaginal, anal, penile, and oropharyngeal cancers.

Methods

Data source

In this retrospective observational study, patients diagnosed with HPV-related cancers were identified within a VHA dataset from 1 October 2013 through 30 September 2018. The VHA database includes deidentified patient information from inpatient, outpatient, laboratory, pharmacy, cost, and vital status files from the largest integrated US health care system, with over 9 million beneficiariesCitation30.

Patient selection

Selected patients were required to be aged ≥18 years and have had continuous medical and pharmacy health plan enrollment for ≥12 months prior to (baseline period) and ≥1 month after the index date. Outcomes were calculated from the index date through to the earliest follow-up date: 24 months, death, or study end.

Patients were categorized as HPV cancer (case) and non-HPV (control) cohorts. Case patients were included in the study if they had either ≥1 inpatient or ≥2 outpatient claims with a primary or secondary diagnosis for one of the following HPV-related cancers: cervical, vulvar, vaginal, anal, penile, or oropharyngeal cancer (Supplementary Table S1: ICD-9/10-CM codes).

The identification period for HPV-related cancer was 1 October 2014 to 31 August 2018. The index date for HPV cancer patients was defined as the first cancer diagnosis date during the identification period. Control patients had no diagnosis claim for any cancer throughout the study period and were assigned an arbitrary index date within the identification period. After cohort assignment, case and control patients were matched based on age, race, cancer group, and sex for non-sex specific cancers (oropharyngeal and anal cancer). The overall case-to-control matching ratio was 1:4. Due to limited sample size, patients with vulvar or vaginal cancer were combined into a single vulvovaginal cancer cohort.

Baseline characteristics

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) score, individual comorbidities, and all-cause HCRU and costs during the 12-month baseline period, were assessed for the case and control cohorts.

Study outcomes

Annual incidence and prevalence were assessed per fiscal year (FY) from 2014 to 2018 and calculated for each HPV-cancer group throughout the study period as cases per million. Annual incidence and prevalence of each HPV-related cancer group was stratified by age; non-sex specific cancers were stratified by sex. Incidence was defined as the number of newly diagnosed patients for the specific HPV-related cancer within each FY. Prevalence was defined as the total number of patients with a specific cancer diagnosis within each FY. All-cause HCRU and costs were examined per patient per year (PPPY) for each HPV-related cancer group. HCRU included mean number of inpatient hospitalizations (including ER visits), mean length of inpatient hospital stay, mean number of outpatient visits (doctor’s office-based visits), and number of pharmacy scripts.

Statistical analysis

Outcomes for the case and control cohorts were evaluated with chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. A generalized linear model (GLM) was used to assess annual all-cause HCRU and costs between the cohorts during the follow-up period. Age, race, baseline CCI score, individual comorbidities, and all-cause inpatient visits were adjusted in the model. Costs were adjusted to 2018 US dollars ($) using the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index from the US Department of Labor. Data analysis was performed using statistical software SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Institutional Review Board approval

As this study did not involve the collection, use, or transmittal of individually identifiable data, it was exempt from Institutional Review Board review. Both the datasets and the security of the offices where analysis was completed (and where the datasets are kept) meet the requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 5,624 case patients were identified in the final sample. The sample sizes for each HPV-related cancer cohort were as follows: 177 cervical, 70 vulvovaginal, 584 penile, 4,537 oropharyngeal, and 256 anal cancer case patients (). Most non-sex specific HPV cancer cohort patients were male (anal cancer: 93%; oropharyngeal cancer: 99%). Overall, ≥70% of the patients across cancer type cohorts were white. Mean ages ranged from 66–72 years except for the cervical and vulvovaginal cohorts, which trended younger, with an average age of 54 and 60 years, respectively. Cases had significantly higher CCI scores as compared with controls (). Patient attrition for case cohorts across HPV-related cancer groups is presented in Supplementary Table S2.

Table 1. Baseline patient characteristics for matched patients with and without HPV-related cancers.

Study outcomes

Incidence and prevalence

Results for the specific cancer types listed below are shown in . Age- and sex-specific prevalence and incidence data are not shown.

Oropharyngeal cancer

Annual oropharyngeal cancer prevalence ranged between 682 and 779 cases per million, and incidence ranged between 86 and 126 cases per million. Individuals aged 55–64 years had the highest prevalence (1,060–1,425 cases per million) and incidence (146–241 cases per million). Patients with the lowest prevalence and incidence were aged 18–44 (14–34 cases per million and 1–5 cases per million, respectively). Men had higher prevalence and incidence rates than women.

Penile cancer

Annual penile prevalence and incidence rates ranged between 67–68 and 12–21 cases per million, respectively. Men aged ≥65 years had the highest prevalence rates (80–102 cases per million), and men aged 18–44 had the lowest rates (1–13 cases per million). For men aged 55–64 years, the incidence rate increased from eight cases in 2016 to 16 cases in 2018.

Anal cancer

Annual anal cancer prevalence and incidence rates ranged between 52–53 and 4–5 cases per million, respectively. Patients aged 55–64 had the highest prevalence and incidence rates (prevalence: 69–99 cases per million; incidence 5–12 cases per million). Patients aged 18–44 years had the lowest prevalence of 1–8 cases per million; no incidence cases were identified among this age group in 2016 and 2018, and 1–3 cases per million were identified for 2015 and 2017. Anal cancer was more prevalent in women than men (44–71 vs 42–52 cases per million, respectively). Among patients aged 55–64 years, incidence of anal cancer increased from 5 to 12 cases between 2015 and 2018.

Cervical cancer

Annual cervical cancer prevalence and incidence ranged between 125–426 and 52–131 cases per million, respectively. From 2017 to 2018, prevalence and incidence rates increased from 97 to 125 and from 32 to 52 cases per million, respectively. Women aged 55–64 years had the highest prevalence and incidence rates, with 152–680 cases per million and 53–170 cases per million, respectively. Patients aged 18–44 years had the lowest prevalence and incidence rates (52–232 and 19–71 cases per million, respectively).

Vulvovaginal cancer

Annual vulvovaginal cancer prevalence and incidence ranged between 51–123 and 21–49 cases per million, respectively. Women aged ≥65 years had the highest prevalence of vulvovaginal cancer over the 5-year period, at 73–437 cases per million. The highest incidence rate occurred in 2015 (437 cases per million). Women aged 18–44 years had the lowest incidence rates during the study, with a range of 0–25 cases per million.

Adjusted health care resource utilization and costs

Average follow-up ranged from 481 days to 597 days among the case cohorts, and from 676 days to 708 days among the control cohorts. During the follow-up period, case patients had significantly higher overall HCRU and costs PPPY compared to control patients. HCRU results for the HPV-related cancers appear in , and costs appear in .

Figure 2. Adjusted annual health care costs for matched patients with and without HPV-related cancers, per patient per year. Abbreviations: Cases, cancer patients; Controls, patients without cancer, p-value was significant (<0.001) across outcomes. Control patients had no diagnosis claim for any cancer throughout the study period and were assigned an arbitrary index date within the identification period. After cohort assignment, case and control patients were matched based on age, race, cancer group, and sex for non-sex specific cancers (oropharyngeal and anal cancer). The overall case-to-control matching ratio was 1:4. Due to limited sample size, patients with vulvar or vaginal cancer were combined into a single vulvovaginal cancer cohort.

Table 2. Adjusted annual health care utilization results for matched patients with and without HPV-related cancers.

Oropharyngeal cancer

Case patients averaged approximately 10.2-times more inpatient hospitalizations (1.43 vs. 0.14, p < 0.0001), 10.8-times longer inpatient stays (10.74 days vs. 0.99 days; p < 0.0001), 2.7-times more outpatient visits (49.28 vs. 18.03; p < 0.0001), and 2.2-times more filled prescriptions (54.22 vs. 24.70; p < 0.0001) as compared with controls. Cases had approximately 8.3-times higher total health care costs ($82,763 vs. $10,017, p < 0.0001) as compared with controls. The main cost driver among cases was inpatient costs ($37,549), which represented 45% of total costs.

Penile cancer

Case patients averaged approximately 6.6-times more inpatient hospitalizations (0.78 vs. 0.12; p < 0.0001), 6.9-times longer inpatient stays (10.18 vs. 1.48; p < 0.0001), 1.8-times more outpatient visits (34.44 vs. 18.73; p < 0.0001), and 1.6-times more filled prescriptions (40.37 vs. 25.09; p < 0.0001) as compared with controls. Cases had approximately 4.7-times higher total health care costs ($42,772 vs. $9,139; p < 0.0001) as compared with controls. The main cost driver among cases was inpatient costs ($20,386), which accounted for 48% of the total costs.

Anal cancer

Case patients averaged approximately 14.9-times more inpatient hospitalizations (1.98 vs. 0.13; p < 0.0001), 55.1-times longer inpatient stays (29.18 vs. 0.53; p < 0.0001), 2.5-times more outpatient visits (51.45 vs. 20.98; p < 0.0001), and 2.4-times more filled prescriptions (70.83 vs. 29.66; p < 0.0001) as compared with controls. Cases had approximately 11.8-times higher total health care costs ($98,146 vs. $8,339, p < 0.0001) as compared with controls, driven predominantly by case inpatient costs ($53,122), which accounted for 54% of the total costs.

Cervical cancer

Case patients averaged approximately 6.72-times more inpatient hospitalizations (0.46 vs. 0.07; p = 0.002), 6.81-times longer inpatient stays (4.70 vs. 0.69 days; p < 0.0001), 1.42-times more outpatient visits (25.23 vs. 17.74; p < 0.0001), and 1.41-times more filled prescriptions (24.45 vs. 17.27; p < 0.0001) as compared with controls. Cases had approximately 2.3-times higher total health care costs ($24,252 vs. $10,402, p < 0.0001) as compared with controls, driven primarily by case outpatient costs ($13,752), which accounted for 57% of total costs.

Vulvovaginal cancer

Vulvovaginal case patients averaged approximately 2.7-times more inpatient hospitalizations (1.74 vs. 0.64; p = 0.002), 3.8-times longer inpatient stays (14.38 vs. 3.83; p < 0.0001), 1.86-times more outpatient visits (32.14 vs. 17.30; p < 0.0001), and 1.79-times more filled prescriptions (40.70 vs. 22.74; p < 0.0001) as compared with controls. Cases had approximately 3.2-times higher total health care costs ($34,801 vs. $10,913, p < 0.0001) as compared with controls. The difference was mainly driven by case outpatient costs ($15,504), which comprised 45% of total costs related to vulvovaginal cancer.

Discussion

This study examined the prevalence and incidence rates of HPV-related cancers and quantified the incremental health care utilization and costs associated with HPV-related cancers in a large sample of VHA enrollees. The results show considerable rates of HPV-related cancers, with annual prevalence ranging from 51 to 682 cases per million across all cancer types in 2018 as well as substantial related economic burden. Unexpected marked decreases in incidence and prevalence after 2015 were observed in our analysis. These trends, however, do not align with reported incidence and prevalence rates in the general US population across the study periodCitation16,Citation22,Citation31,Citation32.

One possible explanation for the observed decreases in the VHA patient population is the implementation of the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014 (VACAA), which instituted the Veterans Choice Program (VCP)Citation18,Citation19,Citation33. Providing access to healthcare networks outside of the VHA system, the VCP reduces wait times and expands specialty care options, especially for female veterans. Consequently, as the present study data were limited to veterans who sought care within the VHA system, the results may underestimate the true disease burden of HPV-related cancer among veterans.

In a review of the literature, the outcomes and clinical presentations of HPV-related cancers were comparable to the general US populationCitation32. The quality of care at VHA facilities, defined by safety and efficacy, was compared in 69 studies. Safety measures that included mortality, morbidity, complications, and other best practices safety measures, were comparable or better than outside healthcare facilities in 22 of 34 publications. Effectiveness, defined by outpatient care, non-ambulatory care, medication management, availability of services, and palliative care, was better or similar at VHA facilities in 20 of 24 studies compared to non-VHA healthcare settingsCitation34. Hospital-level data from 129 VA and 4,010 non-VA hospitals from July 2012–March 2015, were directly evaluated using pairwise comparisons with risk-adjusted rates for 17 outcomes measures. These 17 measures included nine Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Patient Safety Indicators (PSIs), four mortality measures, and four readmission measures. The VHA hospitals had better outcomes than non-VHA hospitals for six of the nine PSIs and were comparable in the remaining three PSIsCitation35. As a specific example, 9,437 cervical cytology specimens from women veterans in South Florida, obtained between 2014 and 2020, found that approximately 90% of high-grade intraepithelial lesions were positive for high-risk HPV (hr-HPV). In this study, the highest rates (25%) of hr-HPV infections were in the third decade of life, with rates of HPV types 16 and 18 in the female veteran population like that in the general US populationCitation36.

The mean ages of patients across the cancer groups in this study ranged from 54–72 years, which was slightly older as compared with the US general population with a mean age between 49 and 69 yearsCitation37. Given the lack of an available vaccination earlier in their lives and the latency period between HPV infection and cancer development, veterans in the older age bracket (55 to ≥65 years) experienced the highest incidence and prevalence of the HPV-related cancers. Those veterans in the 18–44-year age group had the lowest HPV-related cancer rates as some of the group may have received the HPV-vaccine and the time frame was too early for cancer to be detected. Oropharyngeal cancer was the most prevalent HPV-related cancer type within our study population, which aligns with US population estimatesCitation11. Reported US incidence rates of HPV-related cancers from 1999–2015 have included decreases of 1.6% per year for cervical cancer, while oropharyngeal cancer increased at a rate of 2.7% for men and 0.8% for women per yearCitation16.

HPV infection alone is considered to cause 70% of oropharyngeal cancersCitation10. Alone and in combination, the etiologic factors of HPV infection and smoking are associated with high rates of oropharyngeal cancerCitation38. Tobacco smoke contains toxic metabolites causing oxidative stress, epigenetic alterations, immune inhibition, and carcinogenesis with Epstein-Barr virus and HPVCitation39. Although the prevalence of smoking has generally declined in the civilian population, smoking rates among young veterans are like those of the US adult population in the late 1960sCitation40. However, the identification of tobacco use/nicotine dependence within the VHA claims database is generally unreliable, as one study documented a 67% omission rate in coding for nicotine dependenceCitation41.

Unlike the reduction in cervical cancer rates resulting from routine screening gynecological evaluations, the responsibility for the diagnosis of oropharyngeal cancer is generally not assigned to a medical specialty or a routine screening procedure. Oropharyngeal cancers are often discovered when the patient is symptomatic and are most frequently diagnosed by otolaryngologists and dentistsCitation42. Because of a longer latency period between HPV infection and diagnosis of oropharyngeal cancers, most men are in their 50s or 60s when they are diagnosed with oropharyngeal cancer, as reflected in our analysisCitation43.

Our findings show that, after adjusting for baseline demographic and clinical characteristics, patients across all HPV-related cancer types incurred significantly greater HCRU and costs as compared with their control counterparts who did not have an HPV-related cancer. The disease burden from an HPV-related cancer included significantly more inpatient and outpatient visits and a higher number of filled prescriptions. Notably, cases had approximately 4–15-times more inpatient hospitalizations of significantly longer duration, as well as 2–11-times higher total health care costs, as compared with controls. Patients with anal cancer faced a particularly higher inpatient care burden, with approximately 15-times more inpatient hospitalizations and 55-times longer inpatient stays as compared with controls (29 days vs. 0.5 days, respectively). These hospitalizations drove costs that totaled $98,146 for each anal cancer patient vs. $8,339 for a matched control who did not have anal cancer. Similarly, significant cost differentials were observed for all other HPV-related cancer types compared to matched controls: cervical ($24,252 vs. $10,402), vulvovaginal ($34,801 vs. $10,913), penile ($42,772 vs. $9,139), and oropharyngeal ($82,773 vs. $10,017).

The total healthcare costs for HPV-related cases in this VHA system study [2018 US dollars] were comparable to or higher than the treatment of HPV-related cancers in other medical settings outside the VHA system. For vulvovaginal cancer cases treated within the VHA system, this study found that the total annual healthcare costs ($34,801) were similar to the costs reported to treat vulvar cancer (mean $23,600; $15,500–$31,700 [2010 US dollars]) and vaginal cancer (mean $27,100; $20,300–$34,100 [2010 US dollars]) in a younger patient population with fewer comorbiditiesCitation14. Predominantly driven by inpatient costs, the total annual health care costs to treat oropharyngeal and anal cancers and comorbidities were greater than costs reported to treat these HPV-related cancers outside the VHA system. The higher inpatient costs within the VHA system may have also been influenced by socioeconomic factors for veterans, such as lack of social support for care and an extended distance to the VHA facility. The cost ($82,763) to treat oropharyngeal cancer and comorbidities within the VHA system was 8.3-times greater ($10,017) than treatment of comorbidities among controls, and almost twice that ($43,200) to treat oropharyngeal cancer outside the VHA. Similarly, the total annual cost ($98,146) to treat anal cancer and comorbidities within the VHA was 11.8-times greater ($8,339) for study controls and exceeded the cost ($36,200) for the treatment of anal cancer outside the VHA. Outside of the VHA system, the annual direct medical cost of preventing and treating HPV-associated disease is approximately $8.0 billion, with 12% ($1.0 billion) spent in the treatment of HPV-related cancerCitation14.

The contribution of outpatient and inpatient costs for total health care costs also differed by HPV-related cancer type. Total costs for anal and oropharyngeal cancers were mainly driven by inpatient costs, ranging from $20,000–$50,000 annually. Total costs for female cervical and vulvovaginal cancers were mainly driven by outpatient costs, which ranged between $14,000 and $16,000 annually. These high health care costs align with other studies that examined HPV-related cancers (e.g. average cost of treatment within 2 years of diagnosis, totaling $76,000 for penile cancer and $127,531 for anal cancer)Citation27–29,Citation44,Citation45.

The HPV vaccine has proven to be effective in preventing HPV infection, and has been recommended for male and female patientsCitation2,Citation22,Citation32,Citation46. According to a recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention analysis, 33,000 of the 35,900 HPV-related cancers identified between 2013 and 2017 in the US could have been prevented by HPV vaccinationCitation47. In addition, clinical trials indicate that 90% of women up to age 55 years are protected from developing cervical precancer after receiving the vaccineCitation48. Notably, while HPV vaccination has been approved for the prevention of cervical, vulvar, vaginal, penile, and anal cancers globally, the United States is currently the only country that has approved HPV vaccination for the prevention of oropharyngeal and other head and neck cancersCitation49. A significant proportion of the veterans may not have had access to the vaccine previously due to their older age, however HPV vaccination is now recommended for everyone up to age 45 years based on shared clinical decision making in the US. Efforts to increase HPV vaccination rates and screening programs in military populations and eligible veterans could potentially prevent HPV-related cancers among future veterans and result in substantial reductions in the associated clinical and economic burdenCitation9,Citation35,Citation36,Citation50,Citation51.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study of its kind, stratified by year, that analyzes a large, integrated dataset within the US military system at the national level. Nonetheless, results should be interpreted in the context of certain limitations. As with all retrospective analyses, interpretation of these data is limited to observation of associations rather than inference of causality. In addition, all claims data are collected for administrative purposes rather than research and therefore are subject to coding discrepancies and may lack certain clinical information. Since the dataset used in this study does not include clinical confirmation of HPV infection as the direct cause of observed cancers among included patients, the results may be overestimated. However, previous studies have shown that the majority (60–90%) of these cancers are due to HPV infectionCitation4–6. While the HPV vaccine rate was not available in this study, previous studies have found HPV vaccination rates to be between 11% and 38% within the US military and much lower than the civilian populationCitation22–24. While tobacco use is an etiologic factor with HPV-related cancers, the coding of nicotine dependence within the VHA database is inconsistent and unreliableCitation41.

Limitations also relate to HPV-related cancer screening procedures, which are often performed outside the VHA system. Cervical cancer screening among female veterans was commonly performed by many primary care providers outside the VHA system given the VA Choice option and commercial insurance available to female veterans through subsequent employers after military service. Consistent with our data, while low-value cervical cancer screening was rare, only 14% of female veterans of average risk underwent cervical cancer screening within the VHA systemCitation52. These factors of the VA Choice and availability of commercial healthcare insurance options also apply to the screening of other HPV-related cancers. However, screening procedures for many other HPV-related cancers, like oropharyngeal cancer, are not routinely performed within or outside of the VHA system. Due to the lack of routine screening procedures and long latency period between the incident HPV infection and the development of cancer, oropharyngeal cancers are often diagnosed at an advanced stage when symptoms become evident or are found incidentally during routine examinations by otolaryngologists and dentistsCitation38. In addition to HPV infections and screening, our study did not analyze pre-cancer incidence, which is an important biomarker of potential cervical cancers. For future research, it will be highly beneficial to look at the impact of screening of infections and pre-cancers for a more comprehensive assessment of HPV burden in this population. When controlled for race and socioeconomic status (SES), survival rates for both HPV-related and HPV-negative cancers are significantly lowerCitation53. This study did not formally assess the impact of SES on HPV burden, which was another limitation.

Other limitations specific to this study include the generalizability of economic results, which should not be directly extrapolated to patient populations outside the VHA system, as VHA health services are highly subsidized. Moreover, the VHA is a closed system with a database that cannot capture VCP or out-of-network health care encounters, which may have contributed to underestimation of study outcomes. Further research is needed to determine results from out-of-network encounters among the active military and veteran populations.

Conclusions

The present study’s findings of considerable disease burden among VHA patients with HPV-related cancers suggests that US veterans may face lifelong health effects from preventable HPV infections.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This research was funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA.

Declaration of financial/other interests

KS and RSD are employees of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA. AC, TB, and NJ are employees of STATinMED Research, a paid consultant to Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA.

A reviewer on this manuscript has disclosed that they receive a small portion of their salary from a grant that is provided and supported by the American Cancer Society, who received funding from Merck, for the purpose of the “Mission: HPV Cancer Free Quality Improvement Initiative”. The other peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Previous presentation

This research has not been previously presented.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (24.8 KB)References

- Senkomago V, Henley SJ, Thomas CC, et al. Human papillomavirus-attributable cancers - United States, 2012-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(33):724–728.

- HPV Vaccine: Access and use in the U.S. [Internet]. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2021. [cited 2021 Oct 4]. Available at: https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/fact-sheet/the-hpv-vaccine-access-and-use-in-the-u-s/#.

- Genital HPV Infection – Fact Sheet [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control [cited 2021 Oct 4]. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/hpv/stdfact-hpv.htm.

- Fusconi M, Grasso M, Greco A, et al. Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis by HPV: review of the literature and update on the use of cidofovir. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2014;34(6):375–381.

- Braaten KP, Laufer MR. Human papillomavirus (HPV), HPV-related disease, and the HPV vaccine. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2008;1(1):2–10.

- Kreisel KM, Spicknall IH, Gargano JW, et al. Sexually transmitted infections among US women and men: prevalence and incidence estimates, 2018. Sex Transm Dis. 2021;48(4):208–214.

- How many cancers are linked with HPV each year [Internet]? Centers for Disease Control. 2018. [cited 2021 May 17]. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/cases.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control HPV-Associated Cancer Statistics 2020 [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control [cited 2021 May 14]. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/.

- Liao C-I, Caesar MAP, Chan C, et. al. HPV associated cancers in the United States over the last 15 years: has screening or vaccination made any difference? J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(15_suppl):107–107.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: HPV and oropharyngeal cancer. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [cited 2021 Dec 6]. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/basic_info/hpv_oropharyngeal.htm.

- Shay SG, Chang E, Lewis MS, et al. Characteristics of human papillomavirus–associated head and neck cancers in a veteran population. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;141(9):790–796.

- Agan BK, Macalino GE, Nsouli-Maktabi H, et al. Human papillomavirus seroprevalence among men entering military service and seroincidence after ten years of service. MSMR. 2013;20(2):21–24.

- Singh JA, Borowsky SJ, Nugent S, et al. Health‐related quality of life, functional impairment, and healthcare utilization by veterans: veterans' quality of life study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(1):108–113.

- Chesson HW, Ekwueme DU, Saraiya M, et al. Estimates of the annual direct medical costs of the prevention and treatment of disease associated with human papillomavirus in the United States. Vaccine. 2012;30(42):6016–6019.

- Chesson HW, Meites E, Ekwueme DU, et al. Updated medical care cost estimates for HPV-associated cancers: implications for cost-effectiveness analyses of HPV vaccination in the United States. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(7–8):1942–1948.

- Van Dyne EA, Henley SJ, Saraiya M, et al. Trends in human papillomavirus–associated cancers—United States, 1999–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(33):918–924.

- Washington DL, Bean-Mayberry B, Riopelle D, et al. Access to care for women veterans: delayed healthcare and unmet need. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(S2):655–661.

- Panangala SV, Carey MP, Dortch C, et al. Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014 (HR 3230; PL 113-146) [Internet]. Congressional Research Service. 2015 Aug 27 [cited 2021 Oct 11]. Available at: https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R43704.pdf.

- Sayre GG, Neely EL, Simons CE, et al. Accessing care through the veterans choice program: the veteran experience. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(10):1714–1720.

- Høxbroe Michaelsen S, Grønhøj C, Høxbroe Michaelsen J, et al. Quality of life in survivors of oropharyngeal cancer: a systematic review and Meta-analysis of 1366 patients. Eur J Cancer. 2017;78:91–102.

- Conway EL, Farmer KC, Lynch WJ, et al. Quality of life valuations of HPV-associated cancer health states by the general population. Sex Transm Infect. 2012;88(7):517–521.

- Boersma P, Black LI. Human papillomavirus vaccination among adults aged 18-26, 2013-2018 [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020 Jan [cited 2021 Oct 11]. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db354-h.pdf.

- Nobel T, Rajupet S, Sigel K, et al. Using veterans affairs medical center (VAMC) data to identify missed opportunities for HPV vaccination. Hum Vacc Immunother. 2019;15(7–8):1878–1883.

- Buechel JJ. Vaccination for human papillomavirus: immunization practices in the U.S. military. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2018;22(1):104–107.

- Clark LL, Stahlman S, Taubman SB. Human papillomavirus vaccine initiation, coverage, and completion rates among U.S. active component service members, 2007-2017. MSMR. 2018;25(9):9–14.

- Collins MK, Tarney C, Craig ER, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination rates of military and civilian male respondents to the behavioral risk factors surveillance system between 2013 and 2015. Mil Med. 2019;184(Supplement_1):121–125.

- Lairson DR, Fu S, Chan W, et al. Mean direct medical care costs associated with cervical cancer for commercially insured patients in Texas. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;145(1):108–113.

- Lairson DR, Wu CF, Chan W, et al. Medical care cost of oropharyngeal cancer among Texas patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(9):1443–1449.

- Fu S, Lairson DR, Chan W, et al. Mean medical costs associated with vaginal and vulvar cancers for commercially insured patients in the United States and Texas. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;148(2):342–348.

- About VHA [Internet]. U.S. Department of Veterans’ Affairs, Veterans’ Health Administration [cited 2021 Apr 1]. Available at: https://www.va.gov/health/aboutvha.asp.

- United States Cancer Statistics: Data Visualization USCS Data Visualizations – CDC [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control [cited 2021 May 17]. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/uscs/dataviz/index.htm.

- Mix JM, Van Dyne EA, Saraiya M, et al. Assessing impact of HPV vaccination on cervical cancer incidence in women 15–29 years in the United States, 1999–2017: an ecologic study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2021;30(1):30–37.

- Commission on Care Final Report, June 30, 2016. [Internet]. Stars and Stripes [cited 2021 Oct 11]. Available at https://s3.amazonaws.com/sitesusa/wp-content/uploads/sites/912/2016/07/Commission-on-Care_Final-Report_063016_FOR-WEB.pdf.

- O’Hanlon C, Huang C, Sloss E, et. al. Comparing VA and non-VA quality of care: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(1):105–121.:

- Blay E, Jr., DeLancey JO, Hewitt DB, et al. Initial public reporting of quality at veterans affairs vs. non-veterans affairs hospitals. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(6):882–885.

- Syler LB, Stobaugh CL, Foulis PR, et al. Cervical cancer screening in South Florida veteran population, 2014 to 2020: cytology and high-risk human papillomavirus correlation and epidemiology. Cureus. 2021;13(8):e17247.

- Viens LJ, Henley SJ, Watson M, et al. Human papillomavirus–associated cancers—United States, 2008–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(26):661–666.

- Anantharaman D, Muller DC, Lagiou P, et. al. Combined effects of smoking and HPV16 in oropharyngeal cancer. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45(3):752–761.

- Jiang X, Wu J, Wang J, et. al. Tobacco and oral squamous cell carcinoma: a review of carcinogenic pathways. Tob Induc Dis. 2019;17(April):29.

- Brown DW. Smoking prevalence among US veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(2):147–149.

- Horsky J, Drucker EA, Ramelson HZ. Accuracy and completeness of clinical coding using ICD-10 for ambulatory visits. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2017;2017:912–920.

- Tanaka TI, Alawi F. Human papillomavirus and oropharyngeal cancer. Dent Clin North Am. 2018;62(1):111–120.

- Taberna M, Mena M, Pavón MA, et. al. Human papillomavirus-related oropharyngeal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(10):2386–2398.

- Lairson DR, Wu CF, Chan W, et al. Mean treatment cost of incident cases of penile cancer for privately insured patients in the United States. Urol Oncol. 2019;37(4):294.e17–294.e25.

- Wu CF, Xu L, Fu S, et al. Health care costs of anal cancer in a commercially insured population in the United States. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24(11):1156–1164.

- FDA News Release. FDA approves expanded use of Gardasil 9 to include individuals 27 through 45 years old [Internet]. US Food and Drug Administration. 2018. [cited 2021 May 17]. Available at https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-expanded-use-gardasil-9-include-individuals-27-through-45-years-old.

- Cancers Associated with Human Papillomavirus, United States—2013–2017. US Cancer Statistics Data Briefs, No 18 [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control. 2020. [cited 2021 May 12]. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/uscs/about/data-briefs/no18-hpv-assoc-cancers-UnitedStates-2013-2017.htm.

- Kjaer SK, Nygård M, Sundström K, et al. Final analysis of a 14-year long-term follow-up study of the effectiveness and immunogenicity of the quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in women from four nordic countries. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;23:100401.

- Gardasil 9 [Internet]. U.S. Food & Drugs Administration. 2020. [cited 2021 Jul 7]. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/vaccines/gardasil-9.

- Army Shots - Basic Training Vaccinations List [Internet]. US Army Basic [cited 2021 May 17]. Available at: https://usarmybasic.com/about-the-army/army-shots.

- NCI-Designated Cancer Centers Endorse Goal of Eliminating HPV-Related Cancers [Internet]. National Cancer Institute and Affiliated Institutions. [cited 2021 May 12]. Available at http://hpvroundtable.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Cancer-Center-HPVConsensusStatement_FINAL_06.01.2018.pdf.

- Schuttner L, Haraldsson B, Maynard C, et. al. Factors associated with low-value cancer screenings in the veterans health administration. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(10):e2130581.

- Rotsides JM, Oliver JR, Moses LE, et. al. Socioeconomic and racial disparities and survival of human papillomavirus-associated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;164(1):131–138.