?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Objective

To investigate the cost-effectiveness of glycopyrrolate/formoterol compared with tiotropium bromide for the treatment of moderate-to-severe COPD in China and discuss the influence of healthcare policies on the economic evaluation.

Methods

A Markov model with seven disease states was built to evaluate the lifetime cost-effectiveness of glycopyrrolate/formoterol from the perspective of the Chinese healthcare sector. Drug prices both before and after the negotiation were applied to discuss the influence on the economic evaluation results. Exacerbation and adverse event were included in each cycle. The improvement of forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and incidence rate of exacerbation were derived from pooled PINNACLE analysis. Mortality rates from Chinese life tables were adjusted using hazard ratios. Direct medical costs were modeled in accordance with the perspective chosen. Health resource utilization were derived from previous studies and expert’s opinions. Life-years gained, quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), and incidence of exacerbation were simulated as the health outcomes. One-way sensitivity analysis and probability analysis were conducted to explore the robustness of the base case results. Several scenario analyses were also designed.

Results

Glycopyrrolate/formoterol generated an additional 0.0063 LYs and 0.0032 QALYs with lower lifetime costs compared with tiotropium (CNY 27,854 vs. CNY 33,189) and was proved to be the dominant strategy in the base case analysis. The one-way sensitivity analysis confirmed the robustness of the base case results. The probabilities of glycopyrrolate/formoterol being cost-effective were 96.5, 95.7, and 93.0% when CNY 72,000 (1 time GDP per capital), CNY 108,000, and CNY 216,000 were used as thresholds, respectively. Compared with the scenario where price before negotiation was used, the cost-effectiveness based on current price was significantly increased.

Conclusion

Glycopyrrolate/formoterol was demonstrated to be a clinically and cost-effective treatment for moderate-to-severe COPD in China using the latest price. The negotiation policy could increase the cost-effectiveness and benefit the patients.

Introduction

With the increasing demand for healthcare services, changing disease spectrum, aging population and the constraint resources, the reform and improvement of Chinese healthcare policies were needed. Pharmacoeconomics has been used in health decisions, especially the drug price negotiation policy to adjust the National Reimbursement Drug Lists (NRDL), in China since 2017. A mature procedure of the negotiation has been establishedCitation1 and economic evaluation reports and models should be submitted by the pharmaceutical companies for the preparation of the negotiation. This submitted evidence will act as important evidence to calculate the expected price ranges based on thresholds (value of 1 QALY) and the affordability of government budgets during a document reviewing procedure held by the National Healthcare Security Administration (NHSA). If the cost-effective drugs could be incorporated into the NRDL, both patients and healthcare budgets could benefit a lot. Therefore, pharmacoeconomic evidence is indispensable for new drugs launched in the Chinese market and planned to be incorporated into the NRDL.

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is a common, preventable, and treatable disease which is characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation that is due to airway and/or alveolar abnormalities usually caused by significant exposure to noxious particles or gases. Air pollution and exposure to cigarettes in China make COPD a severe healthcare problem threatening people’s healthCitation2. According to a cross-sectional study in China, the overall prevalence of COPD for people aged over 20 was 8.6% and increases to 13.7% for people aged over 40, accounting for almost 100 million people in ChinaCitation3. It was also estimated that the annual direct medical costs for COPD was CNY 12,552 per patientCitation4. Treatment and management of COPD should be individualized considering the severity of the symptoms, risk of exacerbations, comorbidities, and so on. According to the recommendation of Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (2022 report)Citation5, long-acting beta-agonists (LABA) and long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA) were used as level A-evidence in stable COPD and LAMAs have a greater effect than LABAs on exacerbation reduction.

In recent years, combination bronchodilator therapy has been approved and launched in the market, especially the combination of a LABA and LAMA in a single inhaler (LABA/LAMA), which could have a greater improvement in dyspnea and quality-of-life compared to placebo or individual bronchodilator componentsCitation6. Glycopyrrolate/formoterol 7.2 μg/5.0 μg (GFF) was approved by the Chinese Center for Drug Evaluation in May 2020, which is a novel metered dose inhaler (MDI) formulated using the Co-Suspension Delivery Technology for patients with moderate-to-very severe COPDCitation7. Actually, the GFF MDI has been enlisted into the NRDL at the end of 2020. According to the formal announcement, there were a total of 162 drugs with qualifications to enter the 2020 price negotiation and 119 drugs (73.46%) were finally incorporated into the NRDL, with an average price reduction of 50.64%Citation8. Not surprisingly, the price of GFF MDI experienced a significant decrease which would have a huge impact on the cost-effectiveness.

So far, the efficacy and safety of GFF MDI have been compared with those of the mono-components in phase III clinical trials conducted across the US, Asia, Europe, Australia, and New ZealandCitation7,Citation9,Citation10. Among the LABAs or LAMAs compared in the clinical trials, tiotropium bromide (Spiriva Handihaler 18 μg, once daily) is one of the most commonly used drugs for the treatment of COPD in China, whose efficacy and safety has been proven in a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialCitation11.

Based on the clinical evidence and the background of the negotiation policy, this study aimed to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of glycopyrrolate/formoterol compared with tiotropium for the treatment of moderate-to-very severe COPD from a Chinese healthcare sector perspective. In order to discuss the influence under the health policy environment, GFF MDI price before and after the negotiation would be applied in the evaluation.

Materials and methods

Model design

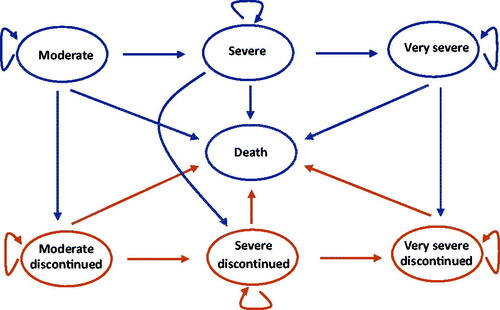

Due to the chronic and progressive characters of COPD, it is necessary to model the disease for a long period. Thus, a Markov model was built to assess the lifetime cost-effectiveness of the GFF MDI. The model adopts a structure based on several previously published modelsCitation12 where the Markov states were classified according to the severity of airflow limitation (). The methods of the classification can be found in . It should be noticed that the mild state was not included in the model because the approved indication of GFF MDI in China is the treatment for moderate-to-very severe COPD. A patient could enter the model from one of the three states representing moderate, severe, and very severe COPD. Then he/she could stay in the present state, progress into the next disease state, discontinue their treatment, or die.

Table 1. Classification of airflow limitation severity in COPDCitation5.

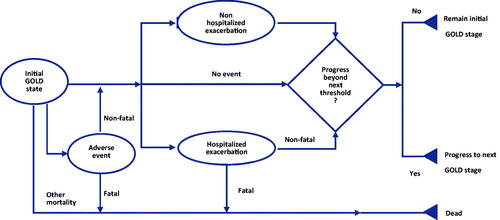

The transition probability from one disease state to the next more severe state was calculated using the improvement of the trough forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1). Low compliance rate is a common problem during the treatment of COPD and could influence the efficacyCitation13. Thus, treatment discontinuation was introduced into the model based on the opinions of the clinicians. Exacerbation COPD and adverse events were assessed and calculated in each cycle (). According to the Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (2022 report)Citation5, exacerbation was classified as severe exacerbation and non-severe exacerbation (including mild and moderate exacerbation) and the patient with severe exacerbation should be treated in hospital. Furthermore, severe exacerbation may increase the risk of death. Since the tolerability and safety of LABA/LAMAs has been provedCitation14, pneumonia was the most common adverse event in the previous cost-effective studies and was included in this study accordinglyCitation15. According to the clinicians’ opinions, the cycle length was set at 3 months, which was a proper interval to capture the change of the disease.

Clinical inputs

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the COPD patients were derived from the Chinese subgroup in a PINNACLE-4 study (NCT02343458)Citation9. A total of 1,740 intent-to-treat COPD patients were included in the study where 466 were Chinese patients. Height which was not collected in PINNACLE-4 was taken from the Report on Chinese Resident’s Chronic Disease and Nutrition 2015Citation16. The distribution of the disease states based on the PINNACLE-4 study was adjusted to exclude the mild state. Detailed characteristics are listed in .

Table 2. Baseline characteristics.

Transition probabilities

Lung function, which is influenced by gender, height, age, human race, and geographic location, is a key factor to calculate the transition probabilities. The widely used FEV1 represents the actual forced expiratory volume in 1 sCitation5. The model states were classified according to FEV1predicted, which is equal to FEV1 for COPD patients divided by FEV1 for normal peopleCitation5. The formula of FEV1 for normal people in East of China was used to calculate the FEV1 based on the baseline characteristics of the simulated patientsCitation17. FEV1 was calculated using the following equation.

The units of height and weight are centimeters and kilograms, respectively. The Gender equals 1 for males and 0 for females. It could be concluded from the equation that the annual decrement of FEV1 for the normal population is 0.0185 liters. The annual FEV1 decrement of 42 ml was derived from a large sample phase III clinical trial (UPLIFT study, NCT00144339)Citation18. To simulate the change of FEV1 in the progression of the disease, the trough FEV1 improvement would be added to the baseline FEV1 at the beginning of the treatment. Then, it was assumed that the FEV1 will be decreased linearly with the speed of 42 ml per year. When patient’s FEV1predicted reaches the lower margin and progresses to the next more severe disease state, the patient will transit to the Markov state accordingly. The reciprocal of the duration time that a patient stays in one disease state is used as the transition probability from the corresponding Markov state to the next more severe Markov state. This is equivalent to the approach adopted by Samyshkin et al.Citation19 The duration time could be calculated using the following equation,

In this equation, T is the duration time of certain disease state, d represents the annual decrease of FEV1 for a COPD patient, while d’ represents that for normal people; π is the actual FEV1predicted after medication and π’ is the marginal value of FEV1predicted to reach the next worse COPD state. FEV1int is the initial FEV1. It should be noticed that the FEV1int has incorporated the initial improvement related to the medication and could be calculated as follows:

FEV1nor is calculated according to the FEV1 equation for normal peopleCitation17. FEV1pre_low and FEV1pre_high represent the low and high margin for the certain COPD state, respectively, thus the average of the low and high margin equal to the mid value of FEV1predicted was used to represent the cohort’s lung function within the certain state. FEV1imp is the improvement of the morning pre-dose trough FEV1 over 24 weeks.

There were several data sources for the FEV1imp in this model, (a) the pooled analysis of PINNACLE 1 (NCT01854645) and PINNACLE 2 (NCT01854658) studies, (b) network meta-analysis (NMA) including 84 randomized clinical trials, (c) smaller NMA which excluded the open label studies. Since most of the data used in the model were derived from PINNACLE studies, considered of the internal consistency of the model, the FEV1imp from the pooled PINNACLE studies was applied in the base case analysis, while that from NMA or smaller NMA were applied in the scenario analysis to test the robustness. The detailed information of pooled PINNACLE analysis has been reported previouslyCitation6. The improvement of FEV1 is listed in and it could be inferred that unlike the similar efficacy of GFF MDI, the FEV1 improvement of tiotropium differed a little.

Table 3. Improvement of the morning pre-dose trough FEV1 over 24 weeks (MD (95% confidence interval), L).

Then the equation for the probability to transit to the next state is listed as follows:

The transition probabilities from any COPD states under treatment to that of treatment discontinuation were based on clinicians’ opinions. The annual discontinuation rate of 30% was applied in the base-case analysis while that of 20% and 40% were used in the scenario analysis. Patients who discontinued treatment would no longer benefit from the improvement of FEV1, thus generating a higher probability to move to the worse state.

The transition probabilities from disease states to death were taken from the all-cause mortality lifetable in ChinaCitation20. Hazard ratios of mortality rate for different disease states were derived from a previous studyCitation21 (listed in ). To avoid double counting of mortality rate due to exacerbation, a hazard ratio of 0.7 derived from the Samyshkin’s method was used to adjust the all-cause mortality rateCitation19.

Table 4. Hazard ratio of all-cause mortality rate.

COPD exacerbation

Exacerbation of COPD is defined as an acute worsening of respiratory symptoms that results in additional therapy. Reducing risk of exacerbation is the important goal for the treatment of COPDCitation22. The risk of exacerbation rises with progression of the disease symptoms and worse lung function. A Poisson regression was performed based on the pooled PINNACLE analysis. The annual baseline rate of moderate exacerbation is given by exponentiation of the constant coefficient in the Poisson regression. Also, the coefficients represented the log incidence rate ratio (IRR) for more severe COPD states and treatment arms. The coefficients of the Poisson regression are listed in .

Table 5. Poisson regression for exacerbations.

Mild exacerbation was excluded from our model due to its low incidence and limited impact on medical cost or health outcomesCitation10. A multicenter, cross-sectional study in China assessed the proportion of severe exacerbation among moderate-to-severe exacerbation patientsCitation23. About 51.86% of exacerbations were severe and this proportion was used in the analysis. A mortality rate of 1.24% due to severe exacerbation was derived from a multicenter, retrospective, observational study in ChinaCitation24.

Adverse events

The ncidence of adverse events was derived from a PINNACLE-3 study (NCT01970878)Citation10. According to the previous cost-effectiveness study of COPDCitation15 and clinicians’ opinion, only pneumonia was included as an adverse event in the first cycle of the model. The 52-week incidence of pneumonia was 2.51% (95% CI = 1.65–3.55%) and 1.33% (95% CI = 0.49–2.57%) for GFF MDI and tiotropiumCitation10, respectively. A case fatality rate of 0.034 was applied in the model to calculate the death due to pneumoniaCitation25.

Costs

Only the direct medical care costs were included as the Chinese healthcare sector perspective was taken. These included drug cost, maintenance cost, exacerbation cost, and adverse event cost. Resources used during the treatment were derived from the Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (2022 report)Citation5 and clinicians’ opinion. The unit prices of the healthcare services were obtained from documents published on the 10 provincial governments’ websites and the median values were used in the base case analysis. Detailed resources used and unit prices are provided in the Supplementary Material. The summary of the cycle costs is listed in .

Table 6. Summary of the cycle costs.

The drug price of tiotropium was CNY 373.26 per 30 puffs (once daily, one puff each time) according to the latest published bidding price. The retail price of GFF MDI was CNY 619 per 120 puffs (twice daily, two puffs each time) before the negotiation. Due to the price confidentiality, the price of GFF MDI is not published, thus the price of CNY 192 per 120 puffs from Menet DatabaseCitation26 was used in the economic model. As a result, the latest price was used in the base case analysis and the price before negotiation was used in the scenario analysis to explore the impact of the price decrease under the negotiation policy.

The costs of outpatient visit, examination, vaccine, and emergency were included in the maintenance cost. For the treatment of exacerbation, costs of inhaled corticosteroids, antibiotics, hospitalization, nursing, and invasive or noninvasive ventilation will be included. It was assumed that life-threatening exacerbation would be treated in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) where a Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter was used for patients. According to the experts’ opinion, life-threatening exacerbation would be treated in theICU and general ward for 20 days. Cost of pneumonia treatment was CNY 15,497 according to a disease burden studyCitation27. Price of previous year will be inflated to the year 2021 using the consumers price indexCitation28. According to the China Guidelines for Pharmacoeconomic Evaluations 2020Citation29, a discounting rate of 5% was used in the analysis.

Utilities

Utility values for each state were derived from a Chinese health-related quality-of-life research study published in 2015. The EuroQol 5-dimension scale was used to collect quality-of-life information of 678 COPD patients from Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and ChengduCitation30. The utility values for COPD states are listed in .

Table 7. Utility values for different COPD states.

The decrement in QALYs of exacerbations were derived from Rutten-Van et al.’s researchCitation31. A decrement of 0.01 QALYs and 0.042 QALYs would be applied in the model for each moderate exacerbation and severe exacerbation, respectively. A decrement of 0.15 QALY will be applied to account for the pneumoniaCitation32.

Model assumptions

It was assumed that, in the Markov model, patients could not transit from a worse COPD state to the former better COPD state. The treatment effect was assumed to start at the beginning of the treatment so that the improvement was added to the patient’s FEV1 at the baseline. Also, it was assumed that, after the improvement, the FEV1 kept decreasing linearly. Life-threatening exacerbation was assumed to be treated in the ICU and general wards.

Sensitivity and scenario analysis

Both one-way sensitivity and probability sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the robustness of the base case results.

One-way sensitivity analysis was conducted using the outcomes of net monetary benefit (NMB). The NMB was calculated using the following equation, where WTP, E, and C represent the willingness-to-pay, effectiveness, and cost of the treatment, respectively. The recommended range of the willingness-to-pay for China is 1–3-times the gross domestic product (GDP) per capital. However, according to previous experience, the actual WTP used in the drug price negotiation was relatively low due to the constraint budget of the Healthcare Security Administration. Thus, a 1.5-times GDP per capital (CNY 108,000) was applied in this analysis.

In the probability sensitivity analysis, normal distribution was applied for the improvement or decrease of the FEV1 and the decrement of QALYs. Log-normal distribution was applied for the incidence rate ratios, hazard ratios, and odds ratios. Beta distribution was applied for the incidence of pneumonia and utilities. Gamma distribution was applied for costs. The 1,000-times Monta Carlo simulation was conducted for the probabilistic sensitivity analysis.

Several scenario analyses were conducted in the study. (1) Original retail price scenario: the retail price (CNY 619 per 120 puffs) of GFF MDI before negotiation will be applied instead of the negotiation price (CNY 192 per 120 puffs). (2) Single initiate state scenarios: All the patients entered the model from one of the moderate, severe, or very severe states rather than the mixed distribution of the COPD states in the base case analysis. (3) Low/high discontinuation scenarios: Different discontinuation rates were applied in the high discontinuation scenario (40% per year) and low discontinuation scenario (20% per year). (4) NMA scenario: FEVs1imp from NMA or smaller NMA for GFF MDI and tiotropium were applied.

Results

Base case analysis

The results of the base case analysis are listed in . The lifetime costs of GFF MDI and tiotropium were CNY 27,854 and CNY 33,189, respectively. GFF MDI generated an additional 0.0063 LYs and 0.0032 QALYs compared with tiotropium. The lifetime exacerbations were similar among the two groups (GFF MDI 7.1938 exacerbations, tiotropium 7.0051 exacerbations). Compared with tiotropium, GFF MDI was estimated to have higher QALYs but lower cost and, therefore, is the dominant option.

Table 8. Base case analysis results.

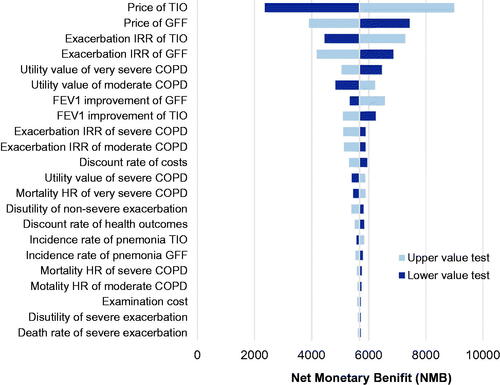

One-way sensitivity analysis

The results of the one-way sensitivity analysis are presented using a tornado diagram in . The most influential parameters are the price of tiotropium and GFF MDI, IRR of exacerbation, and utility values of moderate and severe COPD. However, these factors can not reverse the base case result within the current possible values yet.

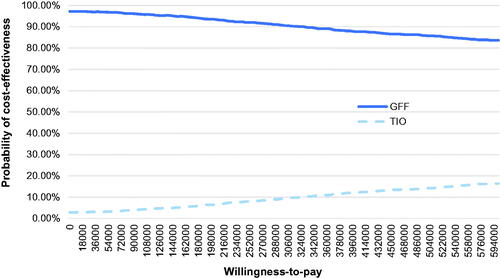

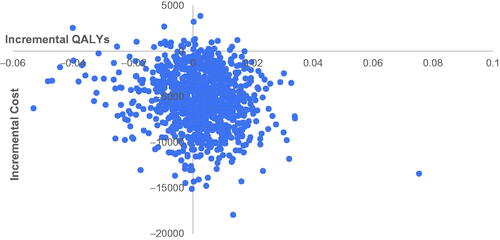

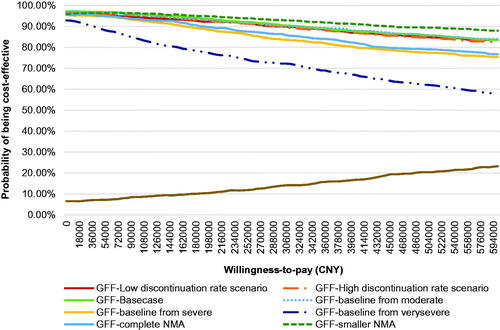

Probability sensitivity analysis

The results of PSA are shown in . It can be found from the cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (CEAC) that the probabilities of GFF MDI being cost-effective were 96.5, 95.7, and 93.0% when CNY 72,000 (1-time GDP per capital), CNY 108,000 (1.5-times GDP per capital), and CNY 216,000 (3-times GDP per capital) were used as WTP, respectively. The cost-effective plane is shown in .

Scenario analysis

The results of scenario analysis are listed in . In light of the retail price of GFF MDI before negotiation (CNY 619 per 120 puffs) being used, there is nothing surprising about the fact that the GFF MDI failed to be the cost-effective strategy. The lifetime cost of GFF MDI treatment was significantly increased compared with that after negotiation (CNY 40,910 compared with CNY 27,854) due to the higher retail price. The incremental cost (GFF MDI vs. tiotropium) was CNY 7,721 and the ICER was CNY 2,442,213/QALY.

Table 9. The results of scenario analysis.

The GFF MDI treatment remained a dominant option in the moderate/severe initial state scenarios, low/high discontinuation rate scenarios, and NMA/smaller NMA scenarios. It was noticeable that when treating the patient with very severe COPD (the very severe COPD scenario), the tiotropium regimen generated an additional 0.0066 QALYs compared with GFF MDI. It may relate to the lower IRR of tiotropium and increasing risk of exacerbation with the severity of the COPD state. However, due to the higher lifetime direct medical cost of tiotropium, the ICER was CNY 712,918/QALY (tiotropium vs. GFF MDI) which is higher than 3-times GDP per capital. Therefore, under such a scenario, GFF MDI could be seen as the cost-saving strategy.

The CEACs of GFF MDI under each scenario are summarized in . The CEACs for different scenarios were closed to each other except for the original retail price scenario.

Discussion

According to the results of the economic evaluation, GFF MDI could generate additional QALYs with savings in direct medical cost compared with tiotropium. The lower price of GFF MDI contributed most to the savings in cost. In the one-way sensitivity analysis, the drug price of tiotropium which moved up or down within 30% was the most influential parameter. The NMB decreased as the reduction of drug price but is always above zero. Compared with the relatively small incremental QALYs, differences in costs may be more determinative. Even though the upwards trend of the tiotropium price is shown in the diagram, it could hardly happen as most of the drug price will decrease due to generic drugs or policies. Furthermore, Chinese drug price polices making the price unpredictable may introduce higher uncertainty in this model.

The IRR of exacerbation of tiotropium and GFF MDI were also important factors, as shown in . It can be explained by the significant impact of exacerbation and is consistent with the conception to reduce the risk of exacerbation when treating COPDCitation22. Despite the higher trough FEV1 improvement, the IRR of GFF MDI was slightly higher compared with that of tiotropium, which was derived from Poisson regression using data from pooled PINNACLE analysisCitation6. The noticeable, open-label nature of the tiotropium arm in PINNACLE trials might result in the lower dropout rate and influence the research end points. However, a long-term efficacy and safety clinical trials have demonstrated that GFF MDI patients have the lower percentage of experiencing COPD exacerbations and longer time to first exacerbation than tiotropiumCitation10. This evidence could not be incorporated into the regression due to the lack of available individual patient data.

The robustness of base case results was verified by the sensitivity analysis except for the original retail price scenario where CNY 619 per 120 puffs was applied instead of the negotiation price of 192 CNY per 120 puffs. This also indicated that the drug price negotiation policy in China significantly increased the cost-effectiveness of the drug by scientific calculations and consultation with the pharmaceutical company. Especially when the health outcomes of the compared regimes were similar with each other, costs turn out to be the determinative factors of the cost-effectiveness. Under such circumstances, the price negotiation could be a preferable way to improve the society welfare.

However, there are still some special circumstances/cases making the price-directed policy well worth consideration. One of the examples is the orphan drugs for rare diseases. Due to the high cost of drug development but small patient pool, the prices of orphan drugs are usually unaffordableCitation33. Rather than bargaining the price into an acceptable range from the NHSA perspective based on the widely used cost-effectiveness threshold, clinical demand, disease burden, clinical efficacy, and disease prevalence should also be evaluatedCitation34. Another example is the situation in which “not cost-effective at a zero price”, which is caused by particularly high cost of background treatment or severely low quality-of-life, indicated that healthcare or medical problems such as ethics or fairness could not be solved by pharmacoeconomic evaluationCitation35. Therefore, costs of the treatments and pharmacoeconomic evaluation could mainly reflect the “cost performance” of the intervention and should not be the determinative tools for the government who should care about the public benefit.

So far, there is a lack of studies exploring the cost-effectiveness of GFF MDI. The cost-effectiveness of tiotropium compared with other LBA/LAMAs has been evaluated. Hoogendoorn et al.Citation36 compared the cost-effectiveness of fixed-dose combination tiotropium/olodaterol with tiotropium or a fixed-dose combination of long-acting β2-agonist/inhaled corticosteroid in Finland, Sweden, and the Netherlands using a patient-level discrete event simulation model and found that tiotropium/olodaterol was the most cost-effective treatment in all three countries. Chan et al.Citation37 compared the cost-effectiveness of indacaterol/glycopyrronium with tiotropium from a health care payer perspective in Taiwan. They found that the indacterol/glycopyrronium is a cost-effective treatment with additional QALYs and costs. Selya-Hammer et al.Citation38 evaluated the cost-effectiveness of tiotropium/olodaterol and tiotropium monotherapy in Italy using a newly developed patient-level Markov model and concluded that tiotropium/olodaterol was a cost-effective treatment. Despite the different methods applied in the analysis, LABA/LAMAs were estimated to be the cost-effective therapy compared with tiotropium monotherapy. This is consistent with what we have found in this study.

There remain a few limitations in this study. First, the efficacy and safety evidence was derived from PINNACLE trials where a few Chinese patients were included. That is a common problem for the development of new drugs outside of China. As a result, it is recommended for pharmaceutical companies to enlist China as one of the centers for clinical trials. Second, when calculating the duration time and transition probabilities, the improvement of FEV1 due to the therapy were added at the beginning of the simulation. Such a method may underestimate the transition probability from the former state to the next worse state in the forepart and overestimate the upcoming probability, especially for patients who discontinued their treatment. However, since the same discontinuation rate was applied for both groups throughout the treatment, the impact may be negligible. Third, the evidence from the open-label arms of tiotropium may overestimate its clinical effect. In the smaller NMA scenario where open-label arms were excluded, the incremental QALYs (GFF MDI vs. tiotropium) were higher compared with the base case. Fourth, clinicians’ opinions were used to estimate the resources used during the treatment due to lack of data. Thus, it is suggested that studies focused on the disease burden should be encouraged in China to provide high-quality evidence for economic evaluation. Also, the healthcare sector was chosen as the perspective in this study and indirect costs were not included. However, the average age to start the simulation is 63, when most Chinese people were retired. It is unnecessary to calculate the charge due to loss of working time. Also, the maintenance medical services are similar between the two groups, other indirect costs could be offset when calculating the incremental cost. Hence, exclusion of the indirect costs could hardly influence the results. Finally, with the approval of more combination therapies, the cost-effectiveness between GFF MDI and other LABA/LAMAs can be further explored.

Conclusion

GFF MDI could be seen as a cost-effective therapy compared with tiotropium bromide from the perspective of the Chinese health care sector. The healthcare policy in China has a positive impact on the improvement of the cost-effectiveness as the result of price reduction and could benefit more patients.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This research has received funding from AstraZeneca (Wuxi) Trading Co., Ltd.

Declaration of financial/other interests

The authors have no other conflict of interest with the subject matter or material discussed in the manuscript apart from that disclosed.

The peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Previous presentation

No previous presentation of this manuscript is declared.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (26.5 KB)Acknowledgements

No assistance in the preparation of this manuscript is declared.

References

- Li K, Liu H, Jiang Q. Overview and analysis on the national medical insurance negotiation drugs over the years: Taking anti-cancer drugs as an example. Anti-Tumor Pharmacy. 2021;11(2):229–235.

- Guan WJ, Zheng XY, Chung KF, et al. Impact of air pollution on the burden of chronic respiratory diseases in China: time for urgent action. Lancet. 2016;388(10054):1939–1951.

- Wang C, Xu J, Yang L, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in China (the China pulmonary health [CPH] study): a national cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2018;391(10131):1706–1717.

- Li J, Feng R, Cui Y, et al. Analysis on the affordability and economic risk for using medicine to treat patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in tier 3 hospitals in China. Chinese Health Economics. 2015;34(9):66–68.

- Gold. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (2022 report); 2021. Available from: https://goldcopd.org/2022-gold-reports-2/

- Martinez FJ, Fabbri LM, Ferguson GT, et al. Baseline symptom score impact on benefits of glycopyrrolate/formoterol metered dose inhaler in COPD. Chest. 2017;152(6):1169–1178.

- Martinez FJ, Rabe KF, Ferguson GT, et al. Efficacy and safety of glycopyrrolate/formoterol metered dose inhaler formulated using co-suspension delivery technology in patients with COPD. Chest. 2017;151(2):340–357.

- NHSA. National Healthcare Security Administration and Ministry of Human Resource and Social Security of the People′s Republic of China announced the national reimbursement drug list 2020; 2020. Available from: http://www.nhsa.gov.cn/art/2020/12/28/art_14_4221.html.

- Lipworth BJ, Collier DJ, Gon Y, et al. Improved lung function and patient-reported outcomes with co-suspension delivery technology glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate metered dose inhaler in COPD: a randomized phase III study conducted in Asia, Europe, and the USA. COPD. 2018;13:2969–2984.

- Hanania NA, Tashkin DP, Kerwin EM, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of glycopyrrolate/formoterol metered dose inhaler using novel Co-Suspension™ Delivery Technology in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2017;126:105–115.

- Zhou Y, Zhong NS, Li X, et al. Tiotropium in early-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(10):923–935.

- Hoogendoorn M, Feenstra TL, Asukai Y, et al. Cost-effectiveness models for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: cross-model comparison of hypothetical treatment scenarios. Value Health. 2014;17(5):525–536.

- Polański J, Chabowski M, Świątoniowska-Lonc N, et al. Medication compliance in COPD patients. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1279:81–91.

- Siddiqui MK, Shukla P, Jenkins M, et al. Systematic review and network Meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate metered dose inhaler in comparison with other long-acting muscarinic antagonist/long-acting β2-agonist fixed-dose combinations in COPD. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2019;13:1753466619894502.

- Capel M, Mareque M, Álvarez CJ, et al. Cost-Effectiveness of Fixed-Dose combinations therapies for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease treatment. Clin Drug Investig. 2018;38(7):611–620.

- NHFPC. Report on Chinese residents′ chronic disease and nutrition. 1.0 edition. Beijing: People′s Medical Publishing House; 2017.

- Mu K, Liu S. Compilation of the normal values of the lung function. Beijing, China: Peking University Medical Press; 1990.

- Tashkin DP, Celli B, Senn S, et al. A 4-year trial of tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(15):1543–1554.

- Samyshkin Y, Kotchie RW, Mork AC, et al. Cost-effectiveness of roflumilast as an add-on treatment to long-acting bronchodilators in the treatment of COPD associated with chronic bronchitis in the United Kingdom. Eur J Health Econ. 2014;15(1):69–82.

- Feng N, Cui H, Zhang Z, et al. Tabulation on the 2010 population census of the people′s republic of China. Beijing: China Statistics Press; 2012.

- Ekberg-Aronsson M, Pehrsson K, Nilsson JA, et al. Mortality in GOLD stages of COPD and its dependence on symptoms of chronic bronchitis. Respir Res. 2005;6:98.

- AECOPD-Panel. Chinese expert′s consensus on the treatment of AECOPD. Int J Respir. 2017;37(14):1041–1057.

- Jia G, Lu M, Wu R, et al. Gender difference on the knowledge, attitude, and practice of COPD diagnosis and treatment: a national, multicenter, cross-sectional survey in China. COPD. 2018;13:3269–3280.

- Zhang J, Zheng J, Huang K, et al. Use of glucocorticoids in patients with COPD exacerbations in China: a retrospective observational study. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2018;12:1753466618769514.

- Suissa S, Patenaude V, Lapi F, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids in COPD and the risk of serious pneumonia. Thorax. 2013;68(11):1029–1036.

- MENET. Drug bidding database; 2021. Available from: https://www.menet.com.cn/.

- Di M, Cao Y, Huang H, et al. Investigation on the expenses of 248 adult patients with community-acquired pneumonia in Dongcheng district, Beijing. Modern Prevent Med. 2014;41(14):2560–2562.

- National BOS. Yearly price index; 2021 [accessed 2020 Aug 24]. Available from: https://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=C01.

- Liu GG. China guidelines for pharmacoeconomic evaluations. 1st edition. Beijing: China Market Press; 2020.

- Wu M, Zhao Q, Chen Y, et al. Quality of life and its association with direct medical costs for COPD in urban China. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:57.

- Rutten-Van MM, Hoogendoorn M, Lamers LM. Holistic preferences for 1-year health profiles describing fluctuations in health: the case of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Pharmacoeconomics. 2009;27(6):465–477.

- Mangen MJ, Huijts SM, Bonten MJ, et al. The impact of community-acquired pneumonia on the health-related quality-of-life in elderly. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):208.

- Jayasundara K, Hollis A, Krahn M, et al. Estimating the clinical cost of drug development for orphan versus non-orphan drugs. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019;14(1):12.

- Yuan S, Wu Y. The establishment of index system for the evaluation of health insurance coverage of orphan drugs in China. Chinese Health Resources. 2021;24(6):1–4.

- Guan X, Wang L, Li H. Cause analysis of “not cost-effective at a zero price” results in pharmacoeconomic evaluation. China Pharmacv. 2021;32(18):2242–2247.

- Hoogendoorn M, Corro RI, Soulard S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of the fixed-dose combination tiotropium/olodaterol versus tiotropium monotherapy or a fixed-dose combination of long-acting β2-agonist/inhaled corticosteroid for COPD in Finland, Sweden and the Netherlands: a model-based study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(8):e049675.

- Chan MC, Tan EC, Yang MC. Cost-effectiveness analysis of a fixed-dose combination of indacaterol and glycopyrronium as maintenance treatment for COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:1079–1088.

- Selya-Hammer C, Gonzalez-Rojas GN, Baldwin M, et al. Development of an enhanced health-economic model and cost-effectiveness analysis of tiotropium + olodaterol Respimat fixed-dose combination for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients in Italy. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2016;10(5):391–401.