Abstract

Aims

How the Chinese government controls the Covid-19 epidemic? This paper aims to answer this question from the perspective of public health expenditure, and policy, and then to help the government to perform better in infectious disease prevention and public health emergency management.

Methods and materials

We reviewed the development phases of the COVID-19 epidemic in China and divided it into four stages (incubation stage, outbreak stage, resolution stage, and stable stage). Then we adopted a content analysis method via MAXQDA2020, to analyze the combined application of four different types of policy tools in different stages with 571 texts of epidemic governance policy from the Chinese central government. We also calculated and compared the Chinese public health expenditure between epidemic and non-epidemic periods. Moreover, we also discussed implications for public health emergency management and for infectious disease prevention and control in China.

Results

(1) in the incubation stage, the potential epidemic has not attracted enough attention from the government; (2) the combination of the 4 types of policies is not only an important reason in controlling epidemic during the outbreak stage and resolution stage, but also the reason why the small-scale epidemic has not expanded in the stable stage; (3) the increasing Chinese public health expenditure, involving public health emergency treatment (114.81 billion yuan), government hospitals (284.84 billion yuan) and major public health service projects (45.33 billion yuan), is another critical reason for the rapid control of the epidemic.

Conclusion and implications

Public health expenditure and policy played an important role in the governance and control of the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Some limitations of China’s infectious disease prevention system and public health emergency management system have been exposed to the public in this epidemic, which the Chinese government needs to improve in the future.

1. Introduction

In early 2020, the COVID-19 epidemic broke out in Wuhan and spread rapidly to become the most serious epidemic and public health crisis since the founding of the People’s Republic of China. This catastrophe has not only crashed economic stability in China but also exerted a huge adverse impact on the economic and social development of most countries in the worldCitation1–4. The cumulative COVID-19 cases were more than 258 million worldwide as of 30 November 2021. However, the proportion of cumulative cases in China is <1% and the COVID-19 epidemic in China was basically under control in a few monthsCitation1.

Obviously, the public health expenditure and policies about epidemic governance were timely and effective in China. What kind of policy tools did the Chinese government adopt during the epidemic? How were these policies combined? How has this combination changed with the progress of this epidemic? How has the combination of policy tools affected the progress of the epidemic? How much does the Chinese government spend on public health? And what is the focus of spending? These are the specific research questions that this paper attempts to answer. The results of these questions will not only enrich the research methods and cases of major public health crisis management but also provide a reference for the control of the COVID-19 epidemic in other countries.

According to the existing literature, most of them studied the epidemic governance, or evaluated the government’s capability and performance in epidemic governance, from the perspective of policy tool application. Forman et al.Citation5 stated that China showed leadership in tackling the COVID-19 epidemic within its borders by implementing stringent measures. They also pointed out that honesty and transparency are very important in the governance of major public health crisis. Mauro and GiancottiCitation6 and Bosa et al.Citation7 studied the policy responses of different regions to COVID-19 in Italy. Hale et al.Citation8 tracked the policy responses to the epidemic in major countries through the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker. Yoo et al.Citation9 systematically evaluated South Korea’s capability of epidemic control. Severe challenges faced by the pandemic by the only nation of comparable population size, India, turned out to be paramount onesCitation10.

However, the government’s public health expenditure and policies are both important for epidemic governance. On the one hand, the efficient implementation of public health policy needs to be realized through the government’s public health expenditureCitation11–13. If the governments have formulated a series of systematic and scientific policy implementation plans, but they couldn’t afford the corresponding public health expenditure due to insufficient fiscal funds, which may eventually lead to the poor effect of policy implementation in controlling the epidemic. On the other hand, when the fiscal funds are limited, the government’s public health expenditure should be used for scientific and effective policiesCitation1,Citation14. If the government spends a lot of money on epidemic governance, but the policy implementation is chaotic, it will only waste money and fail to achieve the expected policy goals.

Therefore, we carry out this research from the perspective of expenditure and policy simultaneously. Firstly, we divided the policies into four kinds (containment and closure policy, economic response policy, health systems policy, and mixed policy), and collected 571 texts of epidemic control policy from the Chinese central government, to analyze the combined application of 4 kinds of policy tools in different stages by content analysis method via MAXQDA2020. Secondly, we clarified the definition, statistical caliber, and content of Chinese public health expenditure, then calculated and compared the Chinese public health expenditure between epidemic and non-epidemic periods.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the progress of the COVID-19 epidemic in China; Section 3 is the methods for policy analysis and Chinese public health expenditure measurement; Section 4 is the result. Section 5 discusses implications for public health emergency management and for infectious disease prevention and control in China; Section 6 is the conclusion.

2. A review of the COVID-19 epidemic in China

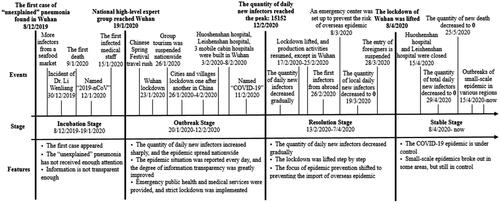

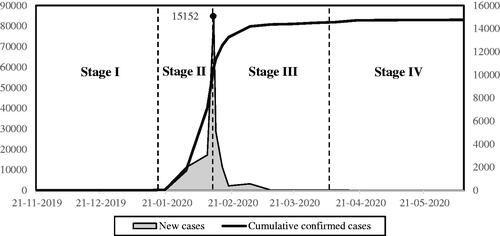

China has been facing an uphill battle in recent two years to control the COVID-19 epidemic. This pandemic embodies different features in different periods, and therefore based on the dynamic change, the progress of COVID-19 could be divided into four stages (see ), namely incubation stage, outbreak stage, resolution stage, and stable stage.

2.1. Incubation stage (2019.12.08–2020.01.19)

The pandemic outbreak since 8 December 2019 in Wuhan, a series of unidentified cases related to Southern China’s seafood market were revealed in some hospitals at the beginning, followed by another four cases from the seafood market carrying similar symptoms on 29th within the same month. After immediate medical observation, the virus was soon confirmed as an acute respiratory disease caused by the 2019 New Coronavirus infection. On receiving the report, the disease control department of the Municipal Health Commission carried out a preliminary epidemiological investigation. However, this had not gained enough attention from the local government. Dr. Li Wenliang posted risks of novel coronavirus pneumonia on the Internet when the epidemic had not spread yet, but he was then accused by the police of “spreading rumors”Citation1.

At first, some medical experts claimed that there was no sign of human-to-human infections of this disease. However, fears and discussions of the epidemic suddenly had bombarded social media ever since the seafood market was shut down overnight on New Year’s Day, 1 January. More panics were aroused ever after the first death occurred one wake later. On the same day, the unknown pathogen was initially identified as New Coronavirus, which was named as 2019-nCoV by WHO on 12 January 2020. It was on 15 January that a healthcare worker who once took care of the patients was diagnosed with New Coronavirus infection, denoting this disease might be highly contagious and bear the risk of human-to-human infections. The disease had instantly evolved into a frantic and massive outbreak over the country, among which Hubei, Guangdong, Henan, Zhejiang, and Hunan were the hardest-hit provinces containing over 1,000 confirmed cases, respectively. Eventually, a panel of experts from the National Health Commission headed for Wuhan for further investigation on 19 January 2020, which meant that the government really began to attach importance to this epidemic.

When in the incubation stage, there were some problems in information disclosure. Some local governments didn’t recognize the epidemic situation and couldn’t prevent the spread of the pandemic timely. There might be two reasons: Firstly, the local governments are not been empowered with the rights of implementing measures, such as the massive lockdown considering the medical and health power distribution system. Secondly, local governments undertake less responsibility for public health measuresCitation1,Citation15.

2.2. Outbreak stage (2020.01.20–02.12)

The number of confirmed cases surged within a short time as the terrible transmissibility of COVID-19, for which lockdown of cities had to be instantly and seriously implemented to dampen the spread. On 23 January, Wuhan officially announced the decision of lockdown. However, the catch was, not all citizens embraced the announcement and it turned out to be too late as a substantial number of people had frantically left from Wuhan before the official publication of lockdown news. On the one hand, millions of migrant workers had already left because of the coming Spring Festival; On the other, citizens were so terribly overwhelmed by the turmoil facing the unprecedented disease of this scale that most of them chose to flee away. Therefore, lockdown measures had been taken all over the country to further cut off the spread of the pandemic. Since then citizens of Wuhan who bore the brunt of the outbreak were not allowed to leave from home, meanwhile, public transportation was all suspended.

To control and relieve the severe outbreak within Wuhan, the government implemented urgent public health policies and medical measures. On 24 January, Chinese New Year’s Eve, the central government mobilized efforts to increase medical supplies to Wuhan. The scene was spectacular as thousands of voluntary medical personnel were closely united and actively engaged in the unprecedented fight against the pandemic. To accommodate more patients and medical personnel, Huoshenshan hospital and Leishenshan hospital were announced to be constructed and then put into use on 3 and 8 February, respectively, and could temporarily hold more than 1,500 people. In addition, Wuhan had also renovated another three spots into three mobile cabin hospitals to offer a total of 3,400 beds to treat novel coronavirus infected patients with mild symptoms since 5 February.

Meanwhile, precautionary measures, such as eliminating intensive activities were carried out to prevent the spread of the virus. On 26 January 2020, China’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism officially announced that the national travel agencies and online travel businesses would suspend group tours and “ticket + hotel” package products. On the same day came the news that the Spring Festival holiday would be extended, and school days were also put off. Besides, all restaurants, cinemas, and theatres were closed.

In addition, artificial intelligence and big data were perfectly put into practice to control the epidemic. On 11 February 2020, the “health QR code” (Alipay R&D) was first launched in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province. Generally, it was used to investigate the trajectory of the public through color dynamic management. Specifically, “Green code” means you are passable, “yellow” and “red” are symbols of risks, that is, you should be in isolation at home or quarantine station. Subsequently, the health code was quickly adopted and spread all over the country.

The epidemic broke out in early February, during which the number of newly confirmed cases surged and then peaked on 12 February (see ). The whole country had mobilized every effort to combat the pandemic. Firstly, the government adopted urgent measures involving public health policies, strict lockdown, and quarantine. Secondly, the government improved the transparency of information by reporting the details of the epidemic every day, which not only demonstrated the government’s determination to fight against the epidemic but also enhanced the confidence of residents. Thirdly, the powerful mix of Artificial Intelligence technology and Big Data technology was an integral part of this battle.

2.3. Resolution stage (2020.02.13–04.07)

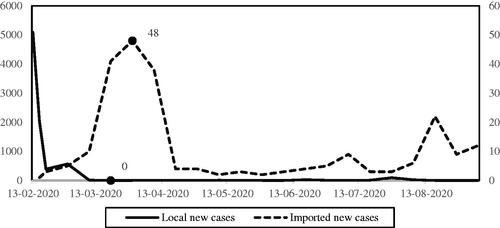

The whole nation had achieved strategic achievements in the war against viruses under the action of a series of policies, after which the lockdown of cities was gradually canceled. After 12 February, the number of newly confirmed cases began to decline (see ) and fell from 15,152 to 391 dramatically within one week only. On 17 February, Hangzhou resumed the operation of urban public transport and urban road passenger transport. After that, various regions began to lift restrictions. By 25 February, traffic control had been lifted in all areas except Wuhan. Work resumption was taking place across China except for Hubei province, the hardest-hit region. On 5 March, there were no new confirmed cases in China except Wuhan.

Although the domestic epidemic had been effectively controlled, the risk of imported cases then became a new focus of the epidemic prevention. A novel coronavirus pneumonia case diagnosed in Ningxia was confirmed on 26 July. Since then, the number of imported cases began to increase, hence China initiated the program to prevent and control imported cases. On 8 March, the Foreign Ministry established an emergency center to prevent the risk of overseas epidemic import. However, that move failed to effectively block cases imported from abroad. On 19 March, the number of newly infected persons decreased to 0, while the number of newly imported cases was still increasing (see ). As a result, foreigners with valid Chinese visas and residence permits are required to suspend their entry.

2.4. Stable stage (2020.04.08–now)

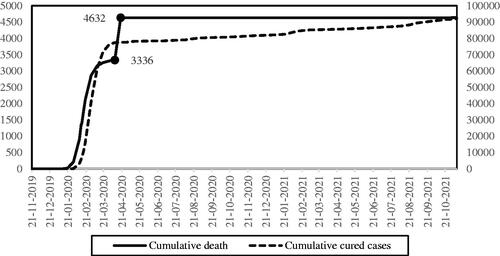

The number of newly confirmed domestic cases stayed zero for 20 days in a row. Wuhan had finally been lifted from the lockdown since 8 April, which was recognized as a symbol of a stage victory, that is, the epidemic situation in China had been controlled basically. Therefore, Huoshenshan and Leishenshan hospitals completed their historical mission and were closed on 15 April. The number of death cases reached 4,632 on 19 April and maintained growth at zero for a long period of time thereafter (see ).

Figure 4. Cumulative death and cured cases. Note. There’s a statistical error about the quantity of cumulative death before 16 April 2020. But this error has been revised at 16 April 2020, hence the line of cumulative death looks weird.

However, small-scale outbreaks continue to turn up in some regions, as is shown in . Fortunately, small-scale epidemics could be effectively controlled within the short term and would not develop into large-scale ones across regions, which is mainly attributed to the Chinese government’s strict epidemic prevention measures. A case in point is the small-scale epidemic in Ruili, Yunnan Province. Two illegal immigrants from Burma were confirmed as Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia when entering Yunan, and the local government immediately conducted a comprehensive nucleic acid examination. As many local residents were also diagnosed, the local government decisively took measures to close the city and suspended schools, shopping malls, cinemas, and other places where there may be dense crowds, which enabled the epidemic situation in Ruili, Yunnan to be effectively controlled in a short time.

Table 1. An incomplete statistic of small-scale epidemic in some areas of China.

3. Methods and materials

3.1. Method for policy analysis

3.1.1. Policy classification

Following the work of Jiang and YuCitation15 and Hale et al.Citation8, this paper divides the policy tools for epidemic governance into four types: containment and closure policy, economic response policy, health systems policy, and mixed policy (see ). Hale et al.Citation8 tracked the policy responses to the epidemic in major countries through the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker and divided all policies into four types: Containment and Closure, Economic Response, Health Systems, and Miscellaneous. Their research comprehensively and objectively summarizes the response policies of major countries in the world. And this classification method was adopted by many related researches, like Jiang and YuCitation15.

Table 2. Classification and features of policy tools in COVID-19 epidemic.

Containment and closure policies aim to create a direct social distance to cut off the transmission of pathogens and prevent the spread of the epidemic, such as lockdown, forced isolation, school closure, etc. The effectiveness of this policy tool has been verified. As Kraemer et al.Citation16 have shown, in the early days of the COVID-19 epidemic in China, population mobility could well explain the spatial distribution of confirmed cases, but this correlation declined after the intervention of population movements. Containment and closure policy tool is mandatory and will disrupt the rhythm of social and economic development, so it should be implemented rapidly to minimize the costCitation17. Moreover, residents may have psychological resistance to this policyCitation18.

Economic response policy tools aim to minimize the damage of epidemic by economic means, such as food subsidy, tax preference, and so on. It is also a kind of government intervention in the market during the epidemic. There are few convenient examples of large-scale global chains of events affecting even the most resilient and rapidly developing Emerging BRICSCitation19 and EM7Citation20 economies. The strengths and weaknesses of macroeconomic responses are clearly visible through the architecture of 2008–2016 recession and macroeconomic crisisCitation21. The COVID-19 epidemic not only caused a negative impact on people’s physical and mental health but also reduced social production and consumption, resulting in stagnation of economic development. Therefore, it is necessary for the government to intervene in the economy to prevent a serious recession. This is a policy tool that residents are happy to accept since it can help people get out of the mud. But it should be noted that the goals of economic response policies are different in different stages of the epidemic. In the outbreak stage, the main goal is to ensure the basic livelihood of residents; in the stable stage, the main goal is to stimulate consumption and promote economic recoveryCitation22.

Health systems policy tools mainly reduce the harm of the epidemic to people by strengthening medical and health technology, such as vaccine research and vaccination. It is clearly that closure policy or economic response policy couldn’t eliminate the epidemic, because the root causes of the epidemic are viruses and infectious diseases. And the epidemic can only be eliminated by medical means and health policy. Therefore, health systems policy tools are essential during the epidemic, especially for countries with large populations like China. Health policy tools have low cost (compared with the other kinds of policy toolsFootnotei), small side effects, strong persistence, and long-term effects, which can improve the overall response-ability to the epidemic situation, compared with the other two types of policies above. Effective Chinese response, adapting throughout the course of pandemics has also served as a convenient milestone event and a landmark strategy for diverse low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs) scattered around the Global SouthCitation23.

In addition to the three types of policy tools above, the remaining ones are miscellaneous, called mixed policy in this paper. For example, the sender or receiver of goods may be exempted from being present to assist the customs in inspection, in the process of international trade. These policy tools can reduce the import risk of the overseas epidemic to a certain extent. The mixed policy tool is different from the other three policy tools, but it may also have something in common with one of them.

3.1.2. Content analysis method

This paper adopts the content analysis method, a kind of quantitative analysis method for text, to analyze the policy text via the MAXQDA2020Footnoteii. This method classifies text materials and simplifies them into some data units which are relevant and easily processed. It achieves the goal of policy analysis in this paper, that is, extract policy tools from policy texts, and then classifies and counts these policy tools.

The first step of the content analysis method is to define the recording unit, that is, to define the basic unit of the text to be classified. There are six common recording units: the word, the word meaning, the sentence, the topic, the paragraph, and the full textCitation24,Citation25. Among them, the topic is a suitable recording unit for the elaboration of a policy tool. As a text unit, the topic contains many elements, namely, the perceiver, the perceiver or actor, the action, and the purpose of actionCitation25. It is roughly similar to the elements contained in policy tools. Policy tools are anything that decision-makers or practitioners adopt or potentially adopt to achieve certain goalsCitation15. So, it should be seen that the basic elements of policy tools are the practitioners, goals, and actions.

The second step is to define categories and items. Categories are the four types of policy tools, and items are specific policy tools in this paper. Items are not determined first but are generated through open coding. The coding process is implemented in strict accordance with the elements of policy tools, to make them mutually exclusive, and to ensure their high validity. While the reliability of content analysis includes stability, repeatability, and certainty. Moreover, reliability is ensured by stability and repeatability: on the one hand, the same one coder encodes the text twice in chronological order and reverse, to avoid coding instability due to coder’s fatigue and cognitive changes; on the other hand, other coders check the text and code again, and then settle the controversial part through negotiation, to ensure the repeatability of the code. After the coding process for items, we get 121 items which appeared 786 times in total (see ).

3.1.3. Analysis of the combination of policy tools

The combination of policy tools cannot be regarded as a simple superposition of several policy tools. It can not only avoid the one-way deviation of the utilization of a single policy tool but also achieve better policy effectCitation26–28. But it should be noted that the effectiveness of the combination of policy tools depends on certain conditions. If multiple policy tools are simply used at the same time, it will not achieve ideal policy results. Only when the combination of policy tools is balanced can it produce positive and ideal resultsCitation29. In addition, the interaction among different policy tools should also be consideredCitation30. Therefore, we should not only investigate which policy tools are used but also investigate how these policy tools are combined.

3.2. Method for public health expenditure measurement and comparison

3.2.1. The definition of public health expenditure

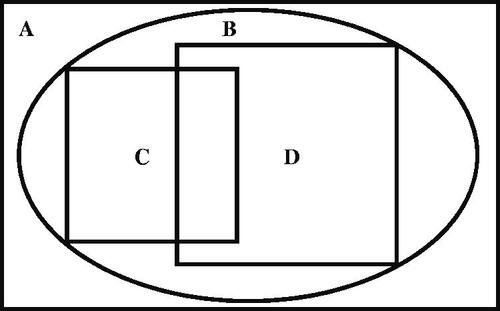

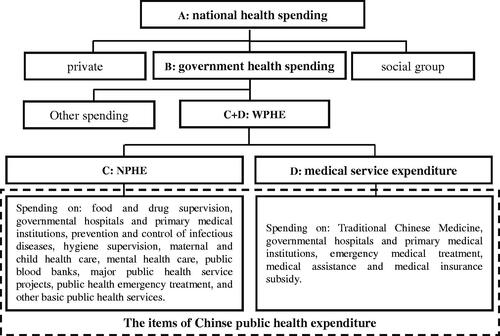

There are 4 main definitions of public health expenditure in previous studies, namely national health spending, government health spending, wide-caliber public health expenditure, and narrow-caliber public health expenditureCitation1. Firstly, national health spending refers to the total spending of a country (or region) on medical care and public health in a certain periodCitation31–35. It includes the healthcare and medical expenditure of privates, social groups, and governments. Secondly, government health spending is the healthcare and medical expenditure of governments, which is a part of national health spending (Rectangle A and Oval B represent the national health spending and the government health spending, respectively in ). The government health spending of China includes not only public health and medical services items, but also family planning and other items. Thirdly, among the items of government health spending, the spending on public health supervision, improvement of residents’ health status, optimization of public health environment, prevention and control of infectious diseases is the third definition, namely the narrow-caliber public health expenditure (NPHE), indicated by Rectangle C. And the spending on the medical care services, institutions, and insurance is called medical service expenditure, indicated by Rectangle D. And the fourth definition is indicated by C + D, namely the wide-caliber public health expenditure (WPHE).

Figure 5. The relationship about the different definitions of public health expenditure. Note. A indicates the national health spending, B indicates government health spending, C indicates the narrow-caliber public health expenditure, D indicates the medical service expenditure, and C + D indicates the wide-caliber public health expenditure.

Therefore, it’s necessary to clarify the definition and content of public health expenditure, to avoid confusion and statistical errors, since there’re various kinds of definition and measurement caliberCitation36,Citation37. We define the Chinese public health expenditure as WPHE following the work of Jin and QianCitation1, mainly considering these reasons: (1) this study aims to evaluate the performance Chinese government in public health during the Covid-19 epidemic; (2) the Chinese government’s spending on public health could be well-measured by WPHE. For example, national health spending (Rectangle A) is obviously beyond government spending. For another example, the NPHE (Rectangle C) strips out the medical service expenditure, which will clearly underestimate Chinese public health expenditure. As is known to all, Chinese public medical institutions have played a very important role in the governance of this pandemic. And, the specific items of Chinese public health expenditure could be seen in and .

Figure 6. The content of different definitions of public health expenditure. Note. The implications of A, B, C, and D in this figure are consistent with those in .

Table 3. Chinese public-health expenditure at national level from 2016–2020.

3.2.2. Measurement and comparison

One of the goals of this paper is to study what the Chinese government did in public health during the COVID-19 epidemic from the perspective of public health expenditure. So, we first measure the Chinese public health expenditure, per capita public health expenditure, the proportion of public health expenditure in GDP, and public health expenditure in total fiscal expenditure from 2016 to 2020. In addition, we list the specific items and data of Chinese public health expenditure. Secondly, we make a comparison about the Chinese public health expenditure between epidemic and non-epidemic periods. We compare not only the total amount of public health expenditure but also the specific expenditure items, to study how much the Chinese government has paid in public health and what items of expenditure have been increased during the epidemic.

3.3. Materials

Firstly, we collect all policy documents of epidemic governance issued by the Chinese central government, because this paper aims to study the policy at the national level. Specifically, if the title or content of a policy document includes the word “YiQing (means epidemic)” or “XinGuan (means COVID-19)”, that document is initially selected; if the content of the initially selected document includes items of practical policy measures (see Section 3.1.2), like school closure, it will be selected as a target document. The earliest policy document at the central government level was issued by the National Health Commission on 20 January 2020, while the latest one was 10 November 2021. The lifting of the lockdown of Wuhan on 8 April 2020 marks the overall control of the COVID-19 epidemic in China, but the small-scale epidemic has been continuing according to the data in . We collected 571 effective policy documents from the State Council and its departments, such as the National Health Commission and the Civil Affairs Bureau.

Secondly, the data of Chinese public health expenditure and fiscal expenditure is from the Finance Yearbook of China (2017–2021). And the data of GDP and population in China is from the China National Bureau of Statistics.

4. Results

4.1. Policy analysis

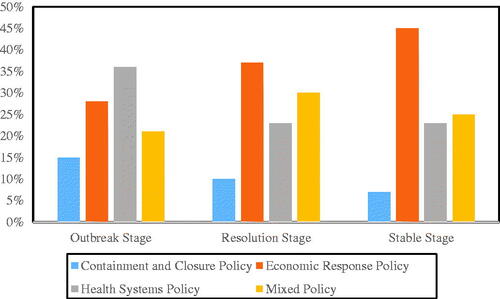

shows the combination of policy tools in different stages of the COVID-19 epidemic in China. The combination of policy tools in different stages is very different. In the outbreak stage, health policy tools accounted for the most, which is the main policy tool, followed by an economic response and mixed policies, and the closure policies were the least. In the resolution stage, the combination of policy tools has changed greatly, becoming dominated by the economic response and mixed policy tools, supplemented by health policy tools. In the stable stage, the combination of policy tools has changed a lot, that is, economic response policy tools account for almost half, while closure policy tools account for very little.

Figure 7. The combination of policy tools in different stages. Note. In fact, there was no policy on epidemic governance at the central government level before 20 January 2020 (namely in incubation stage). At this time, there are only some policies issued by Wuhan municipal government, which are not within the scope of this paper.

In addition, with the progress of the COVID-19 epidemic, the changing trends of various policies are also different. For example, the proportion of closure policies and health policies is getting lower and lower. This is because the epidemic is gradually controlled and the number of patients is gradually decreased, so there is no need for too much closure management and public health services, especially the closure policy which is high cost and difficult to be accepted by residents. On the contrary, the proportion of economic response policies has gradually increased. When the epidemic was at its worst, almost all factories, enterprises, and stores were closed, which had a huge impact on the economy. Therefore, as the epidemic situation is gradually controlled, economic policies to promote the resumption of work and production and support small and micro enterprises are gradually increasing.

Specifically, in the incubation stage, the potential epidemic has not attracted enough attention. This can be proved by the fact that the central government has not issued policy documents about the epidemic governance in this period. Additionally, this can also be proved by some examples. As Section 2 shows, “On 8 December 2019, the first case was confirmed; On 9 January 2020, the first death case; On the same day, the pathogen of unknown pneumonia was identified as New Coronavirus; On 15 January 2020, the first medical staff were infected.” During this period, the government did not take any important and effective measures until the lockdown of Wuhan on 23 January 2020, but it was too late. This lack of attention to the epidemic in the Incubation stage has also occurred in other major countries, such as the USA. Some countries have taken timely and effective policy measures in the Incubation period to quickly control the epidemic, such as South Korea and Japan.

In the outbreak stage, the epidemic spread rapidly from Wuhan to the whole country, and the quantity of daily new cases increased sharply, so the main policy goal is to cut off the transmission route of the epidemic. Therefore, containment and closure policy tools are the key policy tools at this time. Containment and closure policy tools are mainly used to identify existing cases and prevent further mutual infection, while other policy tools are used in conjunction with closure policy tools. After the suspension of most production and service activities, many enterprises and low-income groups faced great survival pressure, so economic response policies were called on, such as credit support and tax relief. And mixed policy tools, such as online transaction processing, made it possible to maintain the necessary communication and operation in society so that the society did not completely stagnate. Moreover, health system policy tools used in conjunction with closure policy tools include epidemic prevention material support, health testing, epidemic knowledge popularization, etc. These health system policy tools enhanced residents’ ability to protect against the epidemic. In this stage, China has adopted many strict and durable closure measures, coupled with active medical and public health policies, which have effectively controlled the epidemic. But many countries did not adopt a sufficiently strict and lasting closure policy because of the economic pressure, which made the previous efforts of the closure policy in vain, such as the United States.

In the resolution stage, the quantity of daily new cases began to decline, which eased the social tension. After the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology issued the first policy to help small and medium-sized enterprises return to work and production on 9 February 2020, the central government paid more and more attention to the restoration of economic development. And economic recovery gradually became two main policy goals together with epidemic control. In this stage, containment and closure policy tools have decreased, and the cooperation and support of the other three types of policy tools for closure policy tools have weakened. On the contrary, economic response policy tools have increased, and health system policy and mixed policy tools have more support and cooperation for economic response policies. Specifically, the content of online administrative services in mixed policy tools is becoming richer and richer, so that enterprises and individuals can carry out some activities even in a relatively closed environment, such as online courses, online diagnosis, and treatment, online office, etc. In addition, the large-scale nucleic acid examination can accurately identify cases, isolate suspected and confirmed cases for observation or treatment, and let healthy people return to work, which greatly eliminates uncertainty and improves the efficiency of closure policy and economic response policy tools. Until the epidemic was gradually controlled, China began to adopt several economic recovery policies, such as tax reduction, consumption subsidies, low-interest loans, and so on. However, many countries are impatient to launch economic stimulus policies when the epidemic has not been controlled, which makes the epidemic in these countries out of control.

In the stable stage, the epidemic situation has been basically controlled, the social blockade has been relaxed, and economic recovery has become the core policy goal. To further promote economic recovery, the government began to stimulate consumption and adopted more economic response policy tools, such as employment promotion and financial subsidies. And there were some new changes in the coordination of other policy tools with economic response policy tools. On the one hand, the online administrative services in the mixed policy tools were further promoted and expanded, which strongly supported the economic policy tools. On the other hand, closure policy and health policy tools mainly provided a safe environment for economic and social activities through epidemic prevention. For example, the health information certification tool broke the barriers in epidemic prevention and control. And the automatic identification of risk area trajectory and health code made the means of epidemic prevention get scientific and simple. Moreover, health system policy tools, such as health information authentication and nucleic acid detection, are efficient and convenient, and gradually replaced closure policy tools, which made the scope of use of high-cost closure policy tools smaller and smaller. But the closure policy tools are still needed to deal with some small-scale regional epidemics, as shows.

4.2. Public health expenditure measurement

shows the public health expenditure and its specific items in the period of 2016–2020. The total public health expenditure is average at 1376.41 billion yuan at this period, which shows a trend of fluctuating growth. Among these specific expenditure items, the medical insurance subsidy costs the most, accounting for more than 45% of total public health expenditure on average; mental health and emergency medical treatment are the two items with the least expenditure, both accounting for <1% of all on average.

Obviously, public health expenditure in 2020 has increased significantly compared with the recent previous years, because this is the most serious year for COVID-19. In absolute terms, the growth of public health expenditure in 2020 is 234.09 billion, which exceeds the total growth in 2016-2019. In relative terms, the growth rate of public health expenditure in 2020 is 16.31%, the highest in the recent 5 years. Meanwhile, this growth rate is much higher than the average growth rate of 5.22% in 2016–2019. Among those items of public health expenditure, the expenditure of public health emergency treatment, government hospitals, and major public health service projects increased the most, they are 114.10, 31.00, and 21.68 billion, respectively. The substantial increase in these expenditures is related to the COVID-19 epidemic.

It is clear that the Chinese government has significantly increased public health expenditure for epidemic governance, especially the spending on public health emergency treatment, government hospitals, and major public health service projects, and has successfully controlled the epidemic. Moreover, it also shows the government’s great attention to the epidemic and its determination to control the epidemic.

However, it doesn’t mean the public health system in China is perfect, it still has some problems. Firstly level of public health expenditure is still low, far lower than that of developed countries. The proportion of public health expenditure in GDP is <1.5%, and the proportion in total fiscal expenditure is <6.5% on average. And this proportion is too low compared with developed countries. For example, public health expenditure in Japan, the United States, and the United Kingdom accounted for 37.23, 22.36, and 20.22% of government expenditure, respectively in 2018Citation1. And in the same year, the proportion of public health expenditure in total government expenditure in these three countries was 7.37, 7.89, and 7.23%, respectivelyCitation1. This is because the government prefers to invest most of its fiscal funds in projects with direct economic benefits, especially infrastructure construction. Secondly, the growth rate of public health expenditure in China is also slow. Chinese public health expenditure increased at an average annual growth rate of 7.95%, from 1240.47 billion in 2016 to 1668.95 billion in 2020. However, the proportion of public health expenditure in GDP and total government expenditure shows a downward trend first and then upward trend, and the proportion in 2020 is almost the same as that in 2016. It indicates that the government needs to pay more attention to public health affairs, and then residents can enjoy the dividends of economic growth from the public health and medical service system. From the economic loss caused by the COVID-19 epidemic, improving the quantity and quality of public health expenditure, improving the public health system, and preventing the recurrence of such major epidemics are also an important way to ensure stable economic growth.

5. An extended discussion

Although the COVID-19 epidemic has been basically controlled in China, the government needs to sum up the lessons of the epidemic from a longer and more general perspective. In fact, the essence of epidemic governance is public health emergency management and the prevention and control of large-scale infectious diseases. Therefore, it is necessary to discuss the implications brought by the epidemic from the above two aspects, to provide references for facing such an epidemic.

5.1. Implication for public health emergency management

Firstly, it is better to build a strong risk early warning mechanism for public health emergencies and strive to control it in the incubation period. Fully tapping the potential of emerging technologies, such as big data, cloud computing, and artificial intelligence is an effective way to further promote the upgrading and iteration of risk early warning mechanisms and improve the early warning ability of public health emergencies. The National Health Commission should cooperate with other relevant departments, such as the National Center for Disease Control and Prevention, the Ministry of Science and Technology, the Emergency Management Department, and enterprises, establish the “Alliance for Public Health Emergencies”, jointly develop the early warning platform for public health emergencies. Then the alliance can make deep use of the advantages of accurate algorithm analysis, such as big data and cloud computing to trace the source of virus when public health emergencies begin to appear, carry out the epidemiological investigation, accurately identify close contacts, and summarize them according to relevant data information. They can incorporate this information into the fuse response threshold scale and access the “public health emergency early warning platform” according to the specific classification of the fuse response threshold. The platform can comprehensively study and judge the epidemic development situation and provide decision-making references for the governments.

Secondly, the emergency medical reserve base should be arranged to improve the supply capacity of emergency medical materials. The key to resolving public health emergencies lies in the rapid and sustainable supply of emergency medical materials, which will directly determine the prevention and control effectiveness and future trend of public health emergencies. Therefore, the government must accelerate the construction of an emergency medical reserve base, which is helpful to build a modern public health emergency management system. Specifically, it’s better to build emergency medical material reserve bases in China’s nine central cities and make use of the superior transportation and advanced pharmaceutical industry foundation of these cities to radiate several surrounding provinces and cities. At the same time, the medical materials in the base can be put on the market regularly. On the one hand, it can meet the needs of the market and adjust the pharmaceutical market. On the other hand, it can also accelerate the circulation and renewal of medical materials in the base, to ensure the quantity and quality of emergency medical materials reserves.

5.2. Implication for infectious disease prevention and control

Firstly, the government should improve and strengthen the prevention and control system of infectious diseases. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is a core and principal part of the prevention and control system of infectious diseases in China, but the CDC has not received enough attention and financial support from the government until the breakout of the COVID-19 epidemicCitation1. As shows, the proportion of expenditure on disease prevention and control in Chinese public health expenditure is <2.8% on average in recent five years. Insufficient attention and investment from the government will directly lead to the slow development of the CDC. Moreover, CDC’s charged technical service project was canceled in recent years, but CDC did not get reasonable financial compensation, resulting in backward equipment and talent shortage in CDC, which further negatively affected its operation and development. The statistical data in 2020 shows, there are only 1.35 disease control personnel per 10,000 population in China, which is lower than the national standard of 1.75 ones. And the CDC lost nearly 3000 employees nationwide in 2018 compared with 2017. In addition, there is another important problem in the CDC, namely unclear positionings and miscellaneous functions. It means that CDC needs to undertake too many functions, but its core functions have not been brought into full play. After the outbreak of COVID-19, the reform of the disease control system has become a consensus. On the one hand, the government should increase financial support for CDC. Sufficient financial funds are the basic premise for equipment renewal and attracting talents. On the other hand, the functions and positioning of CDC should be clarified, so that it could play a real role. Last, but not least one should understand that the CDC style of leadership is also a very important pathway for the countries involved in the Belt and Road initiativeCitation38. Success in overcoming such serious obstacles might be leading to more countries willing to follow the Asian example of adaptation. Such a model appears to be far more feasible for resource-constrained settings compared to those adopted by the wealthy OECD nationsCitation39.

Secondly, infectious disease research needs to be continuously promoted, to lay a solid foundation for the early warning, prevention, and control of the epidemic in the future. There is an interesting feature in the research on infectious diseases: the number of research results tends to peak in the period after the outbreak and control of infectious diseases, and will gradually decline after the epidemic has completely subsided. Especially for China, the research system has some problems which will restrict the continuous promotion of infectious disease research. For example, basic research accumulations, leading and innovative research results are insufficient; there is no effective synergistic mechanism between research, disease control, and clinical treatment; the fiscal funds for infectious disease research are insufficient. Therefore, the government should make improvements in the above aspects, to promote the research of infectious diseases.

6. Conclusion

This paper reviewed the development stages of the COVID-19 epidemic in China, and then study the China government's practice in public health during the epidemic from the perspective of public health expenditure and policy. The result shows: (1) in the incubation stage, the potential epidemic has not attracted enough attention from the government; (2) the combination of the four types of policies is not only an important reason for the rapid control of the epidemic in the outbreak stage and resolution stage, but also an important reason why the small-scale epidemic has not expanded in the stable stage; (3) the substantial increase of Chinese public health expenditure is another important reason for the rapid control of epidemic, especially the expenditure on public health emergency treatment, government hospitals, and major public health service projects; (4) but the level of public health expenditure in China is still too low and far lower than that in developed countries. Finally, we also have a discussion on the implications for public health emergency management and for the prevention and control of the infectious disease.

This paper is relevant for both researchers and policy-makers:

On one hand, this paper provides a feasible method and case for the government in dealing with a major public health crisis. For example, some countries spent a lot of public health expenditure to deal with the epidemic but did not adopt an effective policy combination, which led to the epidemic beyond control. On the contrary, some countries have formulated a series of systematic and scientific policies, but they do not have enough financial funds and not enough public health expenditure, which may eventually lead to poor policy implementation effect.

On the other hand, the results of this paper can provide references for other countries that are trapped in the COVID-19 mire. Firstly, this paper divides policy tools into four categories and analyzes the influence of policy combination on the control of the COVID-19 epidemic. And the result shows that the combination of policies is diverse in different stages of the epidemic. For example, in the outbreak stage, the effect of closure policy is very good; but as the epidemic is gradually controlled, such high-cost and low acceptance closure policies should be reduced, while the policies to promote economic development should be increased. If the government adopts insufficient closure policy tools in the early stage of the epidemic and prematurely implements economic recovery policies when the epidemic is not under control, this policy implementation mode actually disrupts the steps of the epidemic governance. In fact, this is also the main reason for the poor effect of epidemic governance in some countries. Secondly, this paper studies Chinese public health expenditure and its items in recent years and finds that the Chinese government has greatly increased the spending on public health emergency treatment, government hospitals, and major public health service projects during the epidemic period. It provides a reference for other countries on how to allocate public health expenditure under the condition of limited fiscal funds.

However, this paper has some limitations. At outbreak time and scale of the COVID-19 epidemic are different in various regions, which makes each regional government’s public health expenditure and policy are very different. This paper studies the epidemic governance in China as a whole, ignoring the differences between provinces.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

The authors acknowledge funding support from the Major Program Project of the National Social Science Fund of China (No: 19ZDA055), Zhejiang Sci-Tech University (ZSTU) Scientific Research Fund (No: 21092117-Y), and ZSTU Philosophy and Social Sciences Research Prosperity Program (No: 21096075-Y).

Declaration of financial/other relationships

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

HJ, BL, and MJ all made substantial contributions to the conception and design of this study. Data acquisition and analysis were conducted by HJ and BL. All authors took part in the drafting and revising of the manuscript, and gave final approval of the manuscript to be published.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express sincere gratitude to Zhejiang Sci-Tech University for their valuable help in the process of policy analysis.

Notes

i Firstly, the “cost” of policy is not only the money which have been used, but also social and economic costs, for example, almost all enterprises have shut down, and most workers in private enterprises have no source of income, and the resulting negative social impact during the closure period. Second, we all know the cost of health systems policy is not low, but it is lower than other policies in China, because the total costs of “Containment and closure policy” and “Economic response policy” are crazy high!

ii MAXQDA2020 is a professional qualitative and quantitative analysis software with powerful qualitative, quantitative and mixed analysis functions. It can be used to manage data in various formats such as web pages, articles, pictures, audio, online surveys and tables, and can realize free coding and fast search.

References

- Jin H, Qian X. How the Chinese government has done with public health from the perspective of the evaluation and comparison about public-health expenditure. IJERPH. 2020;17(24):9272.

- Krstic K, Westerman R, Chattu VK, et al. Corona-triggered global macroeconomic crisis of the early 2020s. IJERPH. 2020;17(24):9404.

- Neumann-Böhme S, Varghese NE, Sabat I, et al. Once we have it, will we use it? A European survey on willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Eur J Health Econ. 2020;21(7):977–982.

- Sabatello M, Burke TB, McDonald KE, et al. Disability, ethics, and health care in the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(10):1523–1525.

- Forman R, Atun R, McKee M, et al. 12 Lessons learned from the management of the coronavirus pandemic. Health Policy. 2020;124(6):577–580.

- Mauro M, Giancotti M. Italian responses to the COVID-19 emergency: overthrowing 30 years of health reforms? Health Policy. 2021;125(4):548–552.

- Bosa I, Castelli A, Castelli M, et al. Corona-regionalism? Differences in regional responses to COVID-19 in Italy. Health Policy. 2021;125(9):1179–1187.

- Hale T, Petherick A, Phillips T, et al. Variation in government responses to COVID-19. Blavatnik School Government Working Paper. 2020;31:2020–2011.

- Yoo KJ, Kwon S, Choi Y, et al. Systematic assessment of South Korea's capabilities to control COVID-19. Health Policy. 2021;125(5):568–576.

- Chattu VK, Singh B, Kaur J, et al. COVID-19 vaccine, TRIPS, and global health diplomacy: India's role at the WTO platform. Biomed Res Int. 2021;2021:6658070. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/bmri/2021/6658070/

- Atems B. Public health expenditures, taxation, and growth. Health Econ. 2019;28(9):1146–1150.

- Kentikelenis AE, Stubbs TH, King LP. Structural adjustment and public spending on health: evidence from IMF programs in low-income countries. Soc Sci Med. 2015;126:169–176.

- Singh SR, Young GJ. Tax-Exempt hospitals’ investments in community health and local public health spending: patterns and relationships. Health Serv Res. 2017;52:2378–2396.

- Jakovljevic M, Timofeyev Y, Ekkert NV, et al. The impact of health expenditures on public health in BRICS nations. J Sport Health Sci. 2019;8(6):516–520.

- Jiang Y, Yu J. 重大公共卫生危机治理中的政策工具组合运用 [Research on the combined application of policy tools in the management of major public health crises]. J Public Manage. 2020;174:1–9.

- Kraemer MUG, Yang C-H, Gutierrez B, et al. The effect of human mobility and control measures on the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Science. 2020;368(6490):493–497.

- Salathé M, Althaus CL, Neher R, et al. COVID-19 epidemic in Switzerland: on the importance of testing, contact tracing and isolation. Swiss Med Wkly. 2020;150:11–12.

- Van Bavel JJ, Baicker K, Boggio PS, et al. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat Hum Behav. 2020;4(5):460–471.

- Jakovljevic MM. Comparison of historical medical spending patterns among the BRICS and G7. J Med Econ. 2016;19(1):70–76.

- Jakovljevic M, Timofeyev Y, Ranabhat CL, et al. Real GDP growth rates and healthcare spending–comparison between the G7 and the EM7 countries. Global Health. 2020;16(1):1–13.

- Jakovljevic M. Therapeutic innovations: the future of health economics and outcomes research–increasing role of the Asia-Pacific. J Med Econ. 2021;24(sup1):1–5.

- Loayza N, Pennings SM. Macroeconomic policy in the time of COVID-19: a primer for developing countries. Washington: World Bank Group; 2020. p. 147291.

- Jakovljevic M, Liu Y, Cerda A, et al. The global South political economy of health financing and spending landscape – history and presence. J Med Econ. 2021;24(sup1):25–33.

- Bouma JA, Verbraak M, Dietz F, et al. Policy mix: mess or merit? J Environ Econ Policy. 2019;8(1):32–47.

- Weber RP. Basic content analysis. Newbury Park (CA); Sage; 1990.

- Cantner U, Graf H, Herrmann J, et al. Inventor networks in renewable energies: the influence of the policy mix in Germany. Research Policy. 2016;45(6):1165–1184.

- Edmondson DL, Kern F, Rogge KS. The co-evolution of policy mixes and socio-technical systems: towards a conceptual framework of policy mix feedback in sustainability transitions. Res Policy. 2019;48(10):103555.

- Guy PB, Van Nispen FKM. Public policy instruments: evaluating the tools of public administration. New York (NY): Edward Elgar; 1998.

- Costantini V, Crespi F, Palma A. Characterizing the policy mix and its impact on eco-innovation: a patent analysis of energy-efficient technologies. Research Policy. 2017;46(4):799–819.

- Reichardt K, Rogge K. How the policy mix impacts innovation: findings from company case studies on offshore wind in Germany. Environ Innov Soc Trans. 2016;18:62–81.

- Chen G, Inder B, Lorgelly P, et al. The cyclical behaviour of public and private health expenditure in China. Health Econ. 2013;22(9):1071–1092.

- Cookson R, Laudicella M, Donni PL. Measuring change in health care equity using small-area administrative data – evidence from the English NHS 2001–2008. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(8):1514–1522.

- Giannoni M, Hitiris T. The regional impact of health care expenditure: the case of Italy. Appl Econ. 2002;34(14):1829–1836.

- Kelly E, Stoye G, Vera-Hernández M. Public hospital spending in England: evidence from national health service administrative records. Fiscal Studies. 2016;37(3–4):433–459.

- Newhouse JP. Medical-care expenditure: a cross-national survey. J Hum Resourc. 1977;12(1):115.

- Gerdtham UG, Jnsson B. International comparisons of health expenditure: theory, data and econometric analysis. Handb Health Econ. 2000;1:11–53.

- Sensenig AL. Refining estimates of public health spending as measured in national health expenditures accounts: the United States experience. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2007;13(2):103–114.

- Jakovljevic M, Cerda AA, Liu Y, et al. Sustainability challenge of Eastern Europe—historical legacy, belt and road initiative, population aging and migration. Sustainability. 2021;13(19):11038.

- Jakovljevic M, Sugahara T, Timofeyev Y, et al. Predictors of (in) efficiencies of healthcare expenditure among the leading Asian economies–comparison of OECD and non-OECD nations. RMHP. 2020;13:2261–2280.

Appendix

Appendix Table A.1. Some cases of policy text coding.