Abstract

Background

South Africa (SA) has the world’s highest burden of HIV infection, with an estimated 13.7% of the population living with HIV (PLWH/Persons Living With HIV). The early identification of PLWH and rapid engagement of them in HIV treatment are indispensable tools in the fight against HIV transmission. Understanding client preferences for HIV testing may help improve uptake. This study aimed to elicit client preferences for key characteristics of HIV testing options.

Methods

A discrete-choice experiment (DCE) was conducted among individuals presenting for HIV testing at two public primary healthcare facilities in Cape Town, South Africa. Participants were asked to make nine choices between two unlabeled alternatives that differed in five attributes, in line with previous DCEs conducted in Tanzania and Colombia: testing availability, distance from the testing center, method for obtaining the sample, medication availability at testing centers, and confidentiality. Data were analyzed using a random parameter logit model.

Results

A total of 206 participants agreed to participate in the study, of whom 199 fully completed the choice tasks. The mean age of the participants was 33.6 years, and most participants were female (83%). Confidentiality was the most important attribute, followed by distance from the testing center and the method of obtaining a sample. Patients preferred finger prick to venipuncture as a method for obtaining the sample. Medication availability at the testing site was also preferred over a referral to an HIV treatment center for a positive HIV test. There were significant variations in preferences among respondents.

Conclusion

In addition to accentuating the importance of confidentiality, the method for obtaining the sample and the location of sites for collection of medication should be considered in the testing strategy. The variations in preferences within target populations should be considered in identifying optimal testing strategies.

Introduction

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV/AIDS) is one of the pandemics the world is currently facing with approximately 37.7 million people living with HIV/AIDSCitation1. UNAIDS reported great progress in the fight against HIV/AIDS worldwide, although the infection rates are not reducing fast enough to eradicate the pandemic. As of 2020, there were 1.5 million new HIV infections prompting a need for transformative measures to tackle the pandemicCitation2. The response has resulted in 28.8 million accessing HIV treatment as of June 2021Citation2. HIV/AIDS is a major public health problem in South Africa (SA), with an estimated 8.2 million positive cases (13.7% of the population) as of July 2021Citation3. For the population between 15 and 49, 19.5% are HIV positiveCitation4. Therefore, the South African government has acted and committed to achieving the United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS)’ targetsCitation5,Citation6. Strides in achieving the targets and high coverage rely on people-centered delivery strategies and relevant societal enablersCitation5.

HIV testing is the gateway to improving the prevention and treatment of HIVCitation7. The HIV testing service (HTS, formally known as HIV counseling and testing) strategy employs different approaches to ensure the success of the HIV program. These strategies include providing HTS in health facilities, community settings, self-testing, and clinical trial or research settingsCitation8. Given the diversity of potential approaches to the implementation of HIV testing, it is critical to understand client preferences. Various forms of testing exist, including provider-initiated counseling and testing (PICT) and client-initiated counseling and testing (CICT). CICT encompasses home or self-testing, community-based testing, and voluntary counseling and testing (VCT), while PICT is offered in clinical settings to promote access to prevention and treatment servicesCitation8. In PICT provision, protocols such as getting consent and offering pre- and post-testing counseling are observedCitation8,Citation9.

South Africa adopted a test and treat approach to boost the uptake of treatment after testing positiveCitation10. A South African study showed that the availability of medicine at facilities and prevention programs provides incentives for HIV testing and succeeded in increasing the number of tests administeredCitation11. In contrast, failure to provide medication at the testing point can deter testing and cause delays in initiating treatment. Hwang et al.Citation12 reported that stock-outs are prevalent in South Africa, resulting in patients leaving the facilities without their medications. The COVID-19 pandemic appears to have increased uncertainty over shortages of HIV medications in South Africa, including deferment of collecting medication by patients fearing COVID-19 infection during clinic visitsCitation13.

Eliciting client preferences, using discrete-choice experiments (DCE), is increasingly important as support for making healthcare policy decisionsCitation14 and could help improve our understanding and uptake of HIV testing. A discrete choice experiment (DCE) is a survey where participants choose between hypothetical alternatives, each representing a specific product or service that is described by several more and less desirable attributes. Recently, a systematic review of DCEs involving HIV revealed 14 studies conducted in 10 countries, eight of them being from sub-Saharan countriesCitation7. Among those, Ostermann et al.Citation15 noted the benefits of tailoring interventions in conjunction with evidence-based preferences, using the example of a DCE in Tanzania. More recently, using a similar DCE design, another study was conducted in ColombiaCitation16, revealing the importance of distance to the HIV testing center, testing days (weekdays vs. weekends), confidentiality, a method for obtaining the sample, and services in HIV testing, as was observed in TanzaniaCitation15.

To our knowledge, no discrete choice experiment (DCE) studies have been done in South Africa specifically on HIV testing preferences. However, two studies have looked at critical attributes and attribute levels on the delivery of oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among young people in Cape Town and JohannesburgCitation17, and the uptake and effectiveness of HIV prevention products may also rely on pregnancy and STI protectionCitation18. This study aimed to elicit clients’ preferences amongst those presenting for HIV testing in South Africa, using a DCE to provide local evidence for policy and operational decisions.

Methods

A DCE was used to elicit the participants’ preferences for HIV testing. The DCE is a stated preference method that allows participants to choose between hypothetical scenarios of a given service that vary according to a list of predefined attributes and attribute levels. For this study, we adopted similar attributes, levels, and choice sets as those developed for a study in Tanzania by Ostermann et al.Citation15 and further used by Wijnen et al.Citation16in Colombia, due to the adaptability of the levels and attributes to the South African HIV context. The attributes were further validated through literature relative to HIV testing in South AfricaCitation11,Citation19–25.

Attributes and levels

The DCE included five attributes presented in Citation15: testing days, distance to testing, availability of HIV medications at the testing site, confidentiality, and the method for obtaining the sample. The testing days included two levels, namely testing during the week or weekends. In South Africa, one can test at public health facilities, at a general practitioner’s (GP’s) office, at private clinics and pharmacies, at NGO’s mobile outreach facilities, and at facilities for public clinic outreach. Some public facilities are closed during the weekend, and most of the testing is conducted by the private sector. The distance to testing was split into four levels, ranging from testing at home to 20 km away from home. As per South African policy, most public health facilities are within a 5 km radius of the population to ensure access to healthcare in urban areasCitation26. There are three methods for obtaining the sample: venipuncture on the arm, an oral swab in the mouth, and a finger prick.

Table 1. Attributes and attribute levels for the HIV test DCECitation15.

All methods are used in South Africa, with oral swabbing used mainly in home testing and available for purchase over the counter (OTC) as approved by the South African Pharmacy Council in 2017Citation27. The availability of HIV medications at the testing site was split into two levels: collecting at the testing point or referral to an HIV treatment center. Antiretroviral drugs are collected at clinics, or, through a GP, one can be referred to collect government-issued medication at designated pharmacies dispensing units and at automated machine (ATM) pharmacies available in some provinces. Finally, confidentiality had three levels: no one would be aware, the partner would be made aware, and many people would know one had been tested. In South Africa, it is recommended that all sexual partners of an HIV positive be notified, with the consent of the infected, and without breaking confidentiality as per WHO guidelinesCitation28,Citation29. The HTS, the main policy document on HIV testing, stresses the importance of these factors in its quest to increase testing and treatment numbersCitation8.

Experimental design and questionnaire

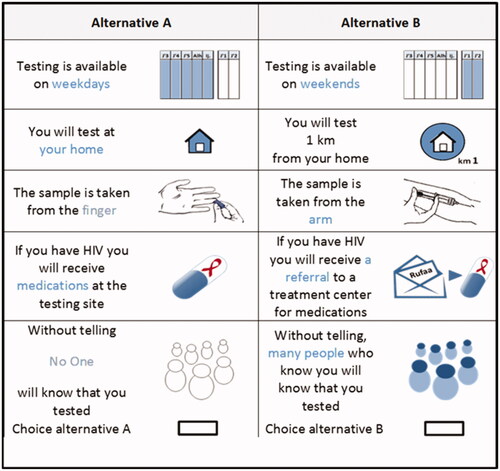

NGene software was used to identify a D-efficient statistical design of 72 choice tasks, allocated as eight blocks/questionnaires with nine choice setsCitation15,Citation30. Each choice set was made up of two alternatives, alternative A and B. An example of a choice set is shown in . Pictures were used to help respondents in understanding the alternatives.

Figure 1. Example of a choice setCitation15.

The questionnaire was comprised of three sections. Part one of the questionnaire contained an explanation of the study, attributes, and levels. Part two was the DCE section, including nine choice sets. The final part included socio-demographic and HIV-related questions. The questionnaire is available from the first author. The English paper-based questionnaires were randomly distributed to clients by a trained university student among those waiting to be tested for HIV at two community health centers. Participants were asked to provide written informed consent. A pilot was conducted with seven respondents for quality assurance, face validity, and to identify any difficulties engaging with the questions. As a result, minor wording changes were made to the questionnaires. In the event of a participant being confused with the task, the interviewer assisted in understanding. Ethics approval was given by the Health Research Ethics Committee of Stellenbosch University (reference number S17/10/208), and the Provincial Health Research Committee of Western Cape Government: Health.

Study population

The study was conducted among persons presenting for HIV testing at the two main public health primary care facilities in Bothasig and Goodwood, Cape Town, South Africa. The facilities provide comprehensive primary health care to approximately 12,000 and 50,000 people, respectively, in their catchment areas. Clients presenting for testing were targeted for the study. The overall impact of the lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic tended to be less marked in the rural clinics in South AfricaCitation31. These findings suggest that HIV services were generally maintained for people already receiving ART. However, engaging new people into care (through HIV testing and subsequent treatment initiation) was impeded by the lockdown, particularly in urban clinicsCitation31. We consecutively approached all individuals aged 18 and older who were waiting to be tested for HIV. For those who provided informed consent, we proceeded to field the paper-based questionnaires.

Statistical analysis

The descriptive statistics for socio-demographic and HIV-related questions were analyzed using Stata 15 software.

The DCE choice data were analyzed using Nlogit version 6 SoftwareCitation32. All parameters were categorical and dummy coded, facilitating the interpretation of model estimatesCitation33. A panel random parameter logit model (RPLM) was used to account for the data’s panel nature, with 1,000 Halton draws and normally distributed random parameters. The random parameter model allowed for the standard deviation of parameter distribution estimates, which captured the heterogeneity in preferencesCitation33. Although the conditional logit model is suitable for many applications, it also has limitations, including the fact that it does not account for unobserved systematic differences in preferences across respondents (preference heterogeneity)Citation33. Due to the latter, the study used the random parameter logit model that allows parameter values to vary across respondentsCitation34. This variation is achieved by specifying a random parameter that has a distribution and estimating the mean (β) and standard deviation of the error term (η) to capture the parameter’s distribution. If the standard deviation is significantly different from zero, this is interpreted as evidence of significant preference variation for the attribute in the sample; significance was measured at p < 0.05. Using dummy coding, we estimated coefficients that represented a preference for each attribute level relative to the omitted level. For the coefficient sign, a negative coefficient implied that an attribute level is less preferred, while a positive sign indicated a positive preference relative to the reference level. The relative importance of attributes was calculated using the range method (calculating the level range for each attribute and dividing each range by the sum of all level ranges).

A sub-group analysis was conducted to determine differences between age groups (18–34 years vs. 35 years or older). A joint model was estimated using interaction terms to assess the significance of the differences between both age groups. A normally distributed random component was added for the dummy variable describing the age group.

Results

Participants’ characteristics

A total of 206 participants agreed to participate in the study, of whom 199 fully completed the questionnaire. The mean age of the participants was 33.6 years (). Most participants (83%) were female. Sixty-one percent (122) fell in the 18–34 age group, representing youth by South African definition, and the rest were 35 and above. Most of the participants had secondary or higher education and were employed. Approximately half of the participants were single or married and in partnership, with a few widowed, divorced, and separated. The HIV status of 6% (12) of the participants was positive, i.e. ten women and two men. These clients were coming in for repeat tests and were included, given that they too may have opinions on the testing processes. The majority reported to have had two or more partners in their lifetime, and only four (2%) had had sex for money. Only eight had other sexually transmitted diseases. More than half had tested five or more times in their lifetimes, while 67% had their last test within the same year. Appendices 1 and 2 provide more details on socio-demographics.

Table 2. Socio-demographic and HIV characteristics of participants.

Random parameter logit model

shows the overall DCE results. Significant differences between levels were observed for three attributes: a method for obtaining the sample, distance, and confidentiality. No significant differences were observed for the distance to the HIV center and time of the week. The relative importance analysis reveals that confidentiality (65%) was the most important attribute, followed by a method for obtaining the sample (15%), distance (10%), collection of medication (6%), and time of testing (4%). Significant variation between respondents (reflected by significant standard deviations) was observed for most attributes, especially for confidentiality and distance.

Table 3. Random parameter logit model results.

Overall, patients preferred a finger prick compared to venipuncture on the arm. For participants who tested positive, collection of medication at an HIV treatment center was less preferred than collecting at the testing site. In terms of confidentiality, there was a significant preference to informing the partner relative to no one knowing, with a high preference heterogeneity (significant estimated standard deviation of 1.40). However, there was an aversion to many people knowing, with the most important significant preference heterogeneity (estimated standard deviation of 1.99).

Sub-group analysis

presents the sub-group analysis according to age. The joined model revealed that three parameters were significantly different between groups. The coefficients 5 km (p = 0.01) and 20 km (p = 0.07) were more important for younger participants, with a negative preference for longer distances away from home, while the older group was indifferent. There were further significant differences between the younger and older groups regarding confidentiality, with the younger group disliking more the premise of many people knowing compared to the older group, and a slight preference for the level “only partner knows” in the younger group.

Table 4. Age sub-group analysis.

Confidentiality, distance, and method for obtaining the sample were significant for the youth group (18–34 years old), with a stronger relative importance for confidentiality (62%), followed by distance (18%) and method for obtaining the sample (13%). In the older group (35 years and above), confidentiality, the method for obtaining the sample, and the collection of medication were significant. This group valued confidentiality the most (48%), followed by the method for obtaining the sample (19%), distance (17%), and collection of medication (10%). There was a positive preference to the partners knowing relative to no one knowing that one had been tested in both groups. However, there was a more significant preference by the youth in comparison with the older group. There was a negative preference to many people knowing of the test for both groups, though considerably less preferred by the youth than the older group. The older group suggested that obtaining the sample is more important than the comparator, with both groups preferring finger prick to venipuncture in the arm or taking an oral sample.

Discussion

The objective of the study was to elicit preferences among clients presenting for HIV testing in South Africa using a Discrete Choice ExperimentCitation35. Overall, our study results suggested that preferences regarding confidentiality, the method for obtaining the sample, and the collection of medication were significant and thus relevant for HIV testing decisions. Confidentiality was the most important attribute in our study, and it is also one of the key components of the South African National HTS, namely the 5Cs during testing: confidentiality, counseling, consent, correct results, and connectionCitation8. The National HTS Policy provides for the use of community-based HTS, which includes testing conducted in mobile outreach facilities, at events, workplaces, places of worship, and in home-based and educational settings as means to mitigate the missed opportunities for testing.

While in our study 83% of the participants were females, this was higher compared to what was observed by Sharma et al.Citation7, who reported over 60% of their study participants were females. In South Africa, more women than men are HIV positive, with HIV prevalence among young women four times higher than their male counterpartsCitation36. Testing appears to be higher for women across all age groups (54%) than for menCitation37. Even though HIV in South Africa is at heightened risk, adolescent girls and young women (ages 15–24) are reported as often reluctant to get tested in health facilities for various reasons, including the fear of encountering judgmental attitudesCitation38. As of 2021, AVERTCitation39 reported that South African men were less likely than women to get tested, arguing that the latter might be partly because women are routinely offered HIV testing through antenatal care and family planning services.

Our study used the same design as the DCE done in Tanzania by Ostermann et al.Citation15, which was also adopted by Wijnen et al.Citation16 in Colombia and further validated through the literature on HIV testing in South AfricaCitation11,Citation19–25. We adopted the same methodology to allow for comparability with other international settings. Ostermann et al.Citation15 used a random community sample, while Wijnen et al.Citation16 utilized a sample from two separate clinics where participants were approached in the waiting room. Important differences in attribute preferences are, however, worth noting.

Ostermann et al.Citation15 found all five attributes significant and distance to be the strongest driver of preference in Tanzania. Our study observed similar findings as what was reported in ColumbiaCitation16, where confidentiality was the most important attribute. Confidentiality was significant in all three settings, thus implying the importance placed on anonymity when testing. Confidentiality was identified as a key aspect of preference in the literatureCitation40. However, even though test centers still prioritize confidentiality, many patients are still afraid of confidentiality violations when visiting the test centers. Our study showed a negative preference for many people knowing one has been tested and a stronger preference for informing a partner. The subgroup analysis showed that younger people were even more concerned that many people could be aware of HIV testing than the older group. This concurs with the findings we observed as maturity was an important determinant for HIV education on the acceptance and disclosure of partner testing. Therefore, HIV education among older people could increase HIV testing and treatment uptake.

Disclosing HIV test results is of enormous concern, reflecting the importance of confidentiality as a barrier to testing. The South African National HTS policy highlights the importance of bringing in a partner for testing and disclosure to partners as part of the couple’s HIV counseling and testing (CHCT). However, partner testing may occur with or without disclosureCitation8. Therefore, the underlying principle is allowing confidentiality, respecting one’s human rights. Though not tested in this study, fear of discordance has resulted in some individuals opting out of testing as it may be seen as a sign of infidelityCitation19,Citation21,Citation35,Citation41. Stigma from family and friends has made HIV counseling and testing (CHCT) more challenging for couples, with some partners choosing to keep their status to themselvesCitation21. Ryan et al.Citation25 found those perceiving the test as confidential 3-times more likely to go for the HIV test than those who had doubtsCitation25.

The method of sample collection showed a high preference for finger pricking as being significantly more desirable than venipuncture in the arm. Several factors have been reported in the literature to influence the choice of the method for obtaining the sample; levels of pain from venipuncture and finger prickingCitation15,Citation42 and accuracy of test resultsCitation7,Citation43. In Tanzania, Ostermann et al.Citation15 reported that participants preferred finger pricking or venipuncture to oral testing in the general population, and porters preferred venipuncture over finger pricking or oral testingCitation35. Strauss et al.Citation44 found the difference between collecting an oral sample and by finger pricking insignificant in Kenya, with first-time testers preferring oral testing. In Nigeria, most participants preferred finger pricking compared to venipunctureCitation45. In the USACitation46, men-having-sex-with-men among youths, as in our study, preferred finger pricking to oral home testing/self-testing (HIVST). Thus, South Africa still has a long way to go, especially in educating its citizens on the differences and cost-effectiveness of testing methodologies.

Our study findings revealed a higher preference for collecting medication at testing sites than at the HIV treatment center. South Africa has been known to struggle with stock-outs of ARVs, which have since been exacerbated with the disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemicCitation12,Citation13. Sibanda et al.Citation47 argued that the availability of ARVs could reduce loss to follow-up by 24%. Sub-group analysis showed older groups having a significant negative preference towards collection at treatment centers, while the youth were indifferent. Though we did not check for the link between the testing site and distance, the latter attribute may be linked. As the results showed, collecting the treatment where one is tested, which should not be too far away from home, may be easier.

The distance was not relevant to testing overall but was a significant factor amongst the youth. Like studies in Kenya, Colombia, and TanzaniaCitation15,Citation16,Citation30,Citation44, more distance between home and place of testing resulted in a negative preference. The reasons given by some participants in a testing survey included lack of ability to pay for transportation and not wanting to go to a clinicCitation23. The stigma surrounding HIV/AIDs has driven some individuals to resort to testing at home, where one performs the test and interprets results without a trained healthcare worker. HIVST has been hailed for bringing convenience and acceptability as an alternative to facility-based testingCitation28. Studies have shown an increase in self-testing kits and the preference for HIVST, at lower cost in most casesCitation20,Citation22,Citation23,Citation48,Citation49. However, HIVST has also been criticized as it misses the pre- and post-testing opportunity to offer emotional support and information on the importance of treatment adherenceCitation23. At the same time, pre- and post-counseling, which is normally characterized by power imbalances between clients and providers, can be a deterrent to testing in clinical or outreach settingsCitation24. Nevertheless, with HIVST at home being insignificant in our study, we can infer preference towards provider-facilitated testing. There is room for further studies on the magnitude of HIVST since its introduction in South Africa, coupled with research on the most appropriate method of sample collection (oral or finger prick) for home testing.

Several factors can be alluded to the dislike of HIV testing, such as long waiting hours, especially at a public health facility, or the availability of testing centers during weekdays versus weekends (working hours vs. non-working hours)Citation28,Citation40,Citation42,Citation50,Citation51. Convenience is a key factor for individuals in deciding where to test for HIVCitation52. Our study found testing days to be insignificant overall, and in the sub-group analysis. These findings contrast with some studies that revealed that weekend testing could be essential for increasing HIV testingCitation35,Citation50,Citation52–55. Weekend testing is noted as a pull factor for those working during the weekCitation35. Concerning the testing day, in Zimbabwe, the AIDS Healthcare Foundation (AFH) noted an increased amount of testing during the weekend, instead of during regular working hoursCitation56. Our findings assume success in South Africa bridging the gap between weekdays and weekends by providing enough resources to reach the communities. Testing days could also play a role in the decision to test or not, despite not being confirmed by our study.

The major strength of our study is that the clinical setting aided in understanding the HIV testing preferences given that our participants were present to have a test conducted and had put thought into getting a test. However, this may have introduced bias in that the participants had already chosen their testing site. We, therefore, did not capture the preferences of those who had not presented themselves for testing, which would equally be important in designing a testing service. It would thus be interesting in future to conduct further preference research comprising of testing clientele from the general public (including people who are not testing) as opposed to the cohort from the facility, as a way to understand the preferences of those who have not made up their minds to test. There are several limitations to the study. First, the study applied the same methodologies and experimental design by Ostermann et al.Citation15 in Tanzania and later adopted by Wijnen et al.Citation16 in Bogota, Colombia. This may be construed as a limitation, as this did not allow us to collect attribute information specifically for our study setting. However, the attributes were validated by literature on South Africa’s testing platformCitation11,Citation19–25 and the HTSCitation8, several with the goal of providing local evidence for policy and operational decisions. Barriers have been reported to be associated with lack of testing and can be divided into the personal, health system, economic, and socio-demographic. Amongst these are stigma, fear of discordance, inconvenient testing hours, location of the testing center, confidentiality, and not trusting testing methodsCitation35. Second, convenience sampling may have introduced biases that limit the generalizability of the results. Finally, similarly to the study of Ostermann et al.Citation15 in Tanzania, we cannot make inferences regarding uptake of testing options as we did not include a “no test” option. With the advent of COVID-19, it is important to explore measures associated with increasing testing at non-clinical and non-crowded settings. It would be interesting to conduct further preference research comprising of testing clientele from the general public as opposed to the cohort from the facility, a way to understand the preferences of those who have not made up their minds to test. Further exploration on the attributes, specifically the most preferred, would be beneficial in policy and operational recommendations tailormade to improve testing within the health system. Attributes not explored in this study such as preferred testing provider, availability of social and emotional support offered by testing, and possible mental health effects of testing are possible areas to explore. Further, investigating preferences and satisfaction with HIV treatment could also complement our research and provide further insights to optimize screening and treatment of HIV patients.

Conclusion

Confidentiality remains the most important attribute in HIV testing. Thus, it should remain a key component of the South African National HIV Testing Strategy, with a possibility of accentuating its importance. In addition, the method for obtaining the sample and collection of medication at testing sites should be considered in the HTS strategy as part of the modalities for reaching different populations and linking care for positive persons. Finally, the variations in preferences for testing options should be considered in deciding optimal testing strategies.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

There was no funding for the study.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants, or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Western Cape Government: Health for allowing us access to the facilities. Second, the facility managers at the two sites made data collection easy. We want to acknowledge Ms. Ife Alaba for assisting with data collection.

References

- UNAIDS. Global HIV & AIDS statistics - Fact sheet [Internet]. 2021. [cited 2022 Feb 24]. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet.

- UNAIDS. UNAIDS warns of millions of AIDS-related deaths and continued devastation from pandemics if leaders don’t address inequalities _ UNAIDS [Internet]. UNAIDS. 2021. [cited 2022 Feb 24]. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/pressreleaseandstatementarchive/2021/november/20211129_unequal-unprepared-under-threat.

- Statistics South Africa. Mid-year population estimates 2021. Vol. P0302. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa; 2021.

- Statistics South Africa. Statistics South Africa: mid-year population estimates. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa; 2020.

- UNAIDS. Prevailing against pandemics by putting people at the Centre. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2020. (UNAIDS/JC3007E).

- UNAIDS. Fast-track: ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030. UNAIDS, editor. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2014. (UNAIDS/JC2686).

- Sharma M, Ong JJ, Celum C, et al. Heterogeneity in individual preferences for HIV testing: a systematic literature review of discrete choice experiments. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;29–30:100653.

- South Africa National Department of Health. National HIV testing services: policy. Pretoria: South Africa National Department of Health; 2016.

- Wambayi J. Rapid HIV testing and HIV prevention in Africa_ a handy tool [Internet]. In On Africa IOA. 2010. [cited 2021 Oct 24]. Available from: www.inonafrica.com.

- Onoya D, Sineke T, Hendrickson C, et al. Impact of the test and treat policy on delays in antiretroviral therapy initiation among adult HIV positive patients from six clinics in Johannesburg, South Africa: results from a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2020;10:e030228.

- Levy NC, Miksad RA, Fein OT. From treatment to prevention: the interplay between HIV/AIDS treatment availability and HIV/AIDS prevention programming in Khayelitsha, South Africa. J Urban Health. 2005;82(3):498–509.

- Hwang B, Shroufi A, Gils T, et al. Stock-outs of antiretroviral and tuberculosis medicines in South Africa: a national cross-sectional survey. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):e0212405–13.

- Mendelsohn AS, Ritchwood T. COVID-19 and antiretroviral therapies: South Africa’s charge towards 90-90-90 in the midst of a second pandemic. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(10):2754–2756.

- Dirksen CD, Utens CMA, Joore MA, et al. Integrating evidence on patient preferences in healthcare policy decisions: protocol of the patient-VIP study. Implementation Sci. 2013;8(1):1–7.

- Ostermann J, Njau B, Brown DS, et al. Heterogeneous HIV testing preferences in an urban setting in Tanzania: results from a discrete choice experiment. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e92100.

- Wijnen BFM, van Engelen RP, Osterman J, et al. A discrete choice experiment to investigate patient preferences for HIV testing programs in Bogotá, Colombia. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2019;19(2):195–201.

- Dietrich JJ, Atujuna M, Tshabalala G, et al. A qualitative study to identify critical attributes and attribute-levels for a discrete choice experiment on oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) delivery among young people in Cape Town and Johannesburg, South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1–13.

- Vickerman P, Quaife M, Kilbourne-Brook M, et al. Terris-Prestholt F. HIV prevention is not all about HIV - using a discrete choice experiment among women to model how the uptake and effectiveness of HIV prevention products may also rely on pregnancy and STI protection. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20(1):1–11.

- Tabana H, Doherty T, Rubenson B, et al. Testing together challenges the relationship: consequences of HIV testing as a couple in a high HIV prevalence setting in rural South Africa. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e66390.

- Richter M, Venter WDF, Gray A. Home self-testing for HIV: AIDS exceptionalism gone wrong. S Afr Med J. 2010;100(10):636–642.

- Rispel LC, Cloete A, Metcalf CA. ‘We keep her status to ourselves’: experiences of stigma and discrimination among HIV-discordant couples in South Africa, Tanzania and Ukraine. SAHARA J. 2015;12:10–17.

- Radebe O, Lippman SA, Lane T, et al. HIV self-screening distribution preferences and experiences among men who have sex with men in Mpumalanga province: informing policy for South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2019;109(4):227–231.

- Gardner J. HIV home testing – a problem or part of the solution. S Afr J Bioeth Law. 2012;5:15–19.

- Engel N, Davids M, Blankvoort N, et al. Making HIV testing work at the point of care in South Africa: a qualitative study of diagnostic practices. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):1–11.

- Ryan S, Hahn E, Rao A, et al. The impact of HIV knowledge and attitudes on HIV testing acceptance among patients in an emergency department in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–10.

- Christian CS. Access in the South African public health system: factors that influenced access to health care in the South African public sector during the last decade. Cape Town, South Africa: University of the Western Cape; 2014.

- Republic of South Africa National Department of Health. The South African Pharmacy Council Government Gazette amendment. The South African Pharmacy Council: Republic of South Africa; 2017. p. 22–25.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines on HIV self-testing and partner notification [Internet]. World Health Organisation. 2016. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/self-testing/hiv-self-testing-guidelines/en/.

- Republic of South Africa National Department of Health. National HIV testing services: policy. Pretoria: Republic of South Africa National Department of Health; 2016.

- Ostermann J, Njau B, Mtuy T, et al. One size does not fit all: HIV testing preferences differ among high-risk groups in Northern Tanzania. AIDS Care. 2015;27(5):595–603.

- Dorward J, Khubone T, Gate K, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on HIV care in 65 South African primary care clinics: an interrupted time series analysis. Lancet HIV. 2021;8(3):e158–e165.

- LIMDEP. NLOGIT: Superior Statistical Analysis Software [Internet]. 2016. [cited 2021 Mar 5]. Available from: https://www.limdep.com/products/nlogit/.

- Brett Hauber A, Marcos González J, Groothuis-Oudshoorn CG, et al. Statistical methods for the analysis of discrete choice experiments: a report of the ISPOR conjoint analysis good research practices task force. Value Health. 2016;19(4):300–315.

- Washington S, Karlaftis M, Mannering F, et al. Statistical and econometric methods for transportation data analysis. Boca Raton (FL): Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2020.

- Mohlabane N, Tutshana B, Peltzer K, et al. Barriers and facilitators associated with HIV testing uptake in South African health facilities offering HIV counselling and testing. Health SA Gesondheid. 2016;21:86–95.

- AVERT. HIV and AIDS in South Africa [Internet]. 2019. [cited 2021 Apr 26]. Available from: https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-around-world/sub-saharan-africa/south-africa.

- AVERT. More choice in community-based HIV testing leads to higher uptake in South Africa [Internet]. 2021. [cited 2021 Apr 26]. Available from: https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-around-world/sub-saharan-africa/south-africa.

- Mbali M. Mbeki’s denialism 1 and the ghosts of apartheid and colonialism for post-apartheid AIDS policy-making. Hist Stud. 2002;1–25.

- AVERT. More choice in community-based HIV testing leads to higher uptake in South Africa [Internet]. 2021. [cited 2022 Mar 5]. Available from: https://www.avert.org/news/more-choice-community-based-hiv-testing-leads-higher-uptake-south-africa.

- Dapaah JM, Senah KA. HIV/AIDS clients, privacy and confidentiality; the case of two health centres in the Ashanti Region of Ghana. BMC Med Ethics. 2016;17(1):1–10.

- Nannozi V, Wobudeya E, Gahagan J. Fear of an HIV positive test result: an exploration of the low uptake of couples HIV counselling and testing (CHCT) in a rural setting in Mukono district, Uganda. Glob Health Promot. 2017;24(4):33–42.

- Strauss M, Rhodes B, George G. A qualitative analysis of the barriers and facilitators of HIV counselling and testing perceived by adolescents in South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):1–12.

- Indravudh PP, Sibanda EL, D’Elbée M, et al. I will choose when to test, where I want to test. Aids. 2017;31(Supplement 3):S203–S12.

- Strauss M, George G, Lansdell E, et al. HIV testing preferences among long distance truck drivers in Kenya: a discrete choice experiment. AIDS Care - Care. 2018;30(1):72–80.

- Nwaozuru U, Iwelunmor J, Ong JJ, et al. Preferences for HIV testing services among young people in Nigeria. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):1–9.

- Merchant RC, Clark MA, Rosenberger JG, et al. Preferences for oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing among social media-using young black, Hispanic, and white men-who-have-sex-with-men (YMSM): implications for future interventions. Public Health. 2017;145:7–19.

- Sibanda EL, d'Elbée M, Maringwa G, et al. Applying user preferences to optimize the contribution of HIV self-testing to reaching the “first 90” target of UNAIDS fast-track strategy: results from discrete choice experiments in Zimbabwe. J Intern AIDS Soc. 2019;22(S1):e25245.

- Maheswaran H, Petrou S, MacPherson P, et al. Cost and quality of life analysis of HIV self-testing and facility-based HIV testing and counselling in Blantyre, Malawi. BMC Med. 2016;14:34.

- Terris-Prestholt F, Sibanda EL. Informing targeted HIV self-testing: a protocol for discrete choice experiments in Malawi. Zambia Zimbabwe. 2016;071.

- Mabuto T, Hansoti B, Kerrigan D, et al. HIV testing services in healthcare facilities in South Africa: a missed opportunity. J Intern AIDS Soc. 2019;22(10):e25367.

- Kelvin EA, Cheruvillil S, Christian S, et al. Choice in HIV testing: the acceptability and anticipated use of a self-administered at-home oral HIV test among South Africans. Afr J AIDS Res. 2016;15(2):99–108.

- Peltzer K, Matseke G. Determinants of HIV testing among young people aged 18 - 24 years in South Africa. Afr Health Sci. 2013;13(4):1012–1020.

- Labhardt ND, Ringera I, Lejone TI, et al. Effect and cost of two successive home visits to increase HIV testing coverage: a prospective study in Lesotho, Southern Africa. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1441.

- Lippman SA, Lane T, Rabede O, et al. High acceptability and increased HIV-testing frequency after introduction of HIV self-testing and network distribution among South African MSM. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;77(3):279–287.

- Wringe A, Moshabela M, Nyamukapa C, et al. HIV testing experiences and their implications for patient engagement with HIV care and treatment on the Eve of “test and treat”: findings from a multicountry qualitative study. Sex Transm Infect. 2017;93(Suppl 3):e052969.

- AIDS Healthcare Foundation Zimbabwe. No Weekends Off for HIV Testing Program [Internet]. 2017. [cited 2021 Feb 4]. Available from: https://www.aidshealth.org/2017/08/no-weekends-off-ahfs-testing-program/.