Abstract

Aims

This study aimed to ascertain the number of patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) and transplant-ineligible patients with multiple myeloma (MM) not recommended by their physicians for optimal drug treatment or who refuse, discontinue, reduce, or skip treatment owing to cost in Japan.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted among hematologists, hematologic oncologists, and oncologists in Japan treating ≥1 patient with CML or ≥5 transplant-ineligible patients with MM per year.

Results

A total of 212 physicians participated: 105 treating patients with CML and 107 treating transplant-ineligible patients with MM. While treatment cost did not lead to non-optimal treatment most patients, physicians reported that they recommended non-optimal treatment to 6.53% of their patients with CML and 1.41% of their transplant-ineligible patients with MM, that 1.51 and 0.35% of their patients, respectively, refused treatment and that 1.97 and 0.71% discontinued treatment owing to treatment cost. However, no significant differences in the effect of treatment cost on recommendation, discontinuation, refusal, or reduction of treatment were observed. Non-recommendation of optimal treatment owing to treatment cost was most common for third-line CML and fourth-line transplant-ineligible MM treatment. Discontinuation due to treatment cost was most common in third-line treatment for both.

Conclusion

Our results show that non-optimal treatment due to treatment cost occurs among some physicians in Japan for patients with CML and transplant-ineligible patients with MM, but it may be limited to a small percentage of patients. Further research is needed to identify the drivers of treatment decisions for physicians and patients, including those involving treatment cost.

Introduction

Cancer incidence is on the rise in Japan, but so too is the availability of effective cancer treatments. Although the number of patients diagnosed with cancer per year increased by about 35% between 2008 and 2018 in Japan, the number of new oncology drugs also surged, leading to an increase in the duration of treatment and drug costsCitation1–3. Between 2015 and 2019, there were about 45 new oncology treatments launched in Japan. Moreover, from 2012 to 2019, expenditures for oncology treatments in Japan increased from 658 billion JPY (6.3 billion USD) to 1.4 trillion JPY (13.3 billion USD), an increase of approximately 112%Citation4,Citation5. Unfortunately, per capita income in Japan increased only 14%, from 2.8 million JPY (26,667 USD) in 2012 to 3.2 million JPY (30,477 USD) in 2019Citation6. Japan’s High-Cost Medical Expense Benefit system is a catastrophic coverage system that covers out-of-pocket costs exceeding approximately 90,000 JPY (865 USD) per month for most patientsCitation7,Citation8. However, 90,000 JPY per month in 2018 represented about 36% of monthly net incomeCitation9. As such, some oncology patients still face a substantial economic burden for treatment.

An initial targeted literature review revealed that very few studies have examined the rationale for refusal or discontinuation of drug treatment by oncology patients in Japan. A study published in 2013 found that among physicians treating these patients, 1.6 inpatients and 1.5 outpatients per month declined the most appropriate treatment for economic reasonsCitation10. Among those, 16% cancelled their treatment altogether, 56% changed their treatment, and 13% interrupted their treatment. The same study found that 16% of patients with colorectal cancer had to withdraw money from their savings and 10% had to borrow money from a relative to cover their treatment costs. Previous studies have also highlighted the importance of treatment cost among physicians and patients. In a survey of 554,500 patients undergoing drug therapy conducted by INTAGE Healthcare (Tokyo, Japan) in 2019, 27% of lung cancer patients, 28% of breast cancer patients, 22% of hematologic cancer patients, and 23% of other cancer patients selected high treatment costs as a reason for dissatisfaction with their current treatment compared with only 15% of all patients, including those with non-oncology conditionsCitation11. Moreover, findings from a study conducted in 2016 suggest that about 40% of physicians in Japan receive a complaint from ≥1 patient per month about their treatment costCitation12. The same study also showed that about two-thirds of physicians in Japan feel that the economics of healthcare should be taken into consideration when choosing treatment for their patients. On the other hand, a discrete choice experiment study conducted in 2018 among Japanese hematologists found that, among 21 different options, drug price was the least important consideration for physicians when selecting patient treatment, suggesting that the effect of cost on treatment decisions may be limited compare to other considerationsCitation13.

Attitudes toward treatment costs may also differ by line of therapy. Studies conducted in Japan, the United States, the United Kingdom, and the European Union suggest that the cost of treatment for oncology patients tends to be higher for therapy in later disease stagesCitation14–20. Later lines of therapy for hematologic cancers, for example, can continue for relatively long periods and may involve combination therapy. A combination of daratumumab, lenalidomide and dexamethasone, for example, was approved in Japan for the treatment of relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (MM) in 2018 and, in some cases, is continued for up to 4 years at an average cost of 1.5 million JPY (14,420 USD) per patient per monthCitation21–23.

The present study aims to identify, from the perspective of Japanese physicians, the degree to which the economic burden of drug treatment for chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) and transplant-ineligible MM is a rationale for patients to receive non-optimal treatment, either because physicians do not recommend optimal drug treatment or because patients refuse, discontinue, reduce, or skip drug treatment. Treatment cost and treatment duration may influence willingness to recommend, undergo, and/or continue treatment. Treatment decisions for CML and transplant-ineligible MM were examined for this study because they represent two different levels of treatment cost and treatment durations: CML typically involves a long treatment duration with a limited monthly cost whereas transplant-ineligible MM involves longer treatment with potentially higher monthly costsCitation21–23,Citation23,Citation24,Citation25. We also examined whether the effect of treatment cost influences the decisions of physicians and patients differently depending on the line of therapy. Lastly, we considered whether physician demographics and attitudes about treatment cost affect their treatment recommendation.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

This prospective, cross-sectional survey included hematologists, hematologic oncologists, and oncologists who treat patients with CML and transplant-ineligible patients MM in Japan. In 2018, there were 2,737 hematologists in JapanCitation26. Among those, approximately 99% worked at hospitals with ≥20 beds. In the same year, there were 8,372 hospitals in Japan, of which 4% (n = 350) were registered as cancer-based hospitals or treatment centersCitation27,Citation28,. The current survey includes 212 hematologists (approximately 8% of all hematologists practicing in Japan) in 212 unique facilities, including 40% (n = 140) of all cancer-based hospitals and treatment centers.

Physicians were identified from a registered panel of Japanese physicians practicing in Japan maintained by Plamed Inc. (Tokyo, Japan), a subsidiary of INTAGE Healthcare. Plamed maintains a panel of approximately 81,000 physicians employed at healthcare facilities in Japan, including 29% (n=∼800) of all hematologists. Aside from their specialty, inclusion criteria for the survey participants included full-time employment as a physician in Japan and provision of consent to participate in an online survey. Moreover, physicians had to have treated ≥1 patient with CML and/or ≥5 patients with transplant-ineligible MM in the past 12 months with drug therapy. The survey was completed by 105 physicians treating patients with CML and 107 physicians treating transplant-ineligible patients with MM. The CML physicians provided data for 1,057 patients whom they considered for treatment in the past year (10.0 patients/physician). For those treating transplant-ineligible patients with MM, the total number was 1,708 (15.9 patients/physician). Physicians were provided with an honorarium for their participation in line with a fair market value.

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki and that are consistent with Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices and the applicable laws and regulations of Japan. Moreover, this study adhered to the European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association (EphMRA) Code of Conduct.

Data collection

Data collection was completed between August 7, 2020 and August 17, 2020. A survey comprising 22 questions was developed by the authors. Two physician employees of AbbVie GK (Tokyo, Japan) reviewed the survey and provided comments to improve its comprehension. Physicians were contacted to answer an initial online screening questionnaire. Those meeting the study inclusion criteria were immediately invited to participate in the main online survey.

The survey’s initial questions related to the physician’s background, such as specialty, type of facility where primarily employed, years of experience, and their Japanese Society of Hematology (JSH) certification status. Then, physicians were asked to identify their optimal treatment regimen for CML and transplant-ineligible MM and the number of patients they recommend for optimal treatment (by line of therapy) as well as their rationale for not recommending such treatment. Next, physicians were asked about the number of patients who refused treatment, discontinued treatment, reduced their dose, or skipped a dose owing to side effects, insufficient efficacy, treatment cost, or other reasons, by line of therapy. Lastly, physicians were asked about their attitude concerning treatment cost and the general characteristics of patients who typically dropout of treatment owing to cost, such as the patient age, occupational status, family composition, presence of symptoms, and distance from the hospital (as a proxy for degree of rural dwelling).

Statistical methods

The primary outcome for this study was overall rates of non-recommendation of optimal treatment by physicians and patient rates of refusal, discontinuation, reduction, and skipping of treatment in CML and transplant-ineligible MM due to economic burden, according to physicians. Trends pertaining to these behaviors by physicians and patients were also examined. Lastly, the analysis was stratified based on physician demographics and attitudes concerning treatment cost.

Quantitative data collected were analyzed by INTAGE Healthcare using Microsoft Excel (2016) and statistical testing was conducted using SPSS Statistics v. 22 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). A descriptive analysis of the data was performed using summary statistics for categorical and continuous data. For categorical data, frequencies and proportions are provided. A chi-square test was used to examine differences in physician characteristics for those treating CML and those treating transplant-ineligible MM. Student t test was used to consider the statistical difference in the percentage of patients per year who receive non-optimal treatment owing to treatment cost by line therapy relative to patients overall and relative to 1st line therapy. A Student t test was also used to determine whether there is statistical difference in the percentage of patients who receive non-optimal treatment owing to cost by line therapy relative to patients overall for different physician characteristics, such as specialty, age, type of facility, and attitude toward treatment cost. A p-value of ≤0.10 based on a Student t test was assumed to indicate statistically significant difference. Missing data were not an issue; the online survey method prevented its occurrence.

Results

Characteristics of study participants

summarizes the characteristics of the study respondents. Physicians treating patients with CML versus transplant-ineligible MM more commonly included oncologists (11 vs. 0%), physicians aged 20–49 years (68 vs 53%), and physicians primarily working at university hospitals (50 vs. 25%). Conversely, transplant-ineligible MM physicians were more commonly certified by the JSH (90 vs. 74%) and treated more patients per year (mean, 15 vs. 8).

Table 1. Characteristics of treating physicians.

Non-optimal treatment due to treatment cost

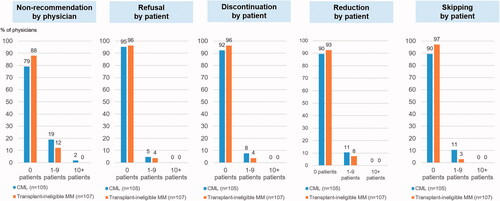

shows the percentage of patients who were considered for or started treatment in the past year and received non-optimal treatment owing to cost (also presented by line of therapy). While treatment cost was not an issue for most patients, CML physicians did not recommend an optimal regimen to 6.53% of their patients per year because of cost. Moreover, 1.51% of these patients refused treatment owing to cost and, among patients who began treatment, 1.97% discontinued, 4.17% reduced their dose, and 3.48% skipped a dose owing to cost. This suggests that 10–20% of patients with CML overall may receive non-optimal treatment owing to treatment cost. Although the percentage of patients that refuse optimal third-line treatment was significantly higher for CML compared to those that refuse optimal first-line therapy, there were otherwise no statistically significant differences observed in the effect of treatment cost on recommendation, refusal, or discontinuation of treatment or on dose reduction or skipping doses due to intention to treat, certification by the Japan Society of Hematology, or line of therapy for CML. While the differences by line therapy of therapy were generally not significant, non-recommendation of optimal treatment and refusal of treatment due to treatment cost was most commonly reported for patients with CML in third-line treatment (7.41 vs. 6.53% overall and 3.09 vs. 1.51% overall, respectively). Discontinuation of treatment due to cost among these patients was most commonly reported for first-line treatment (2.60 vs. 1.97% overall) and reduction of dose due to cost was most commonly reported for second-line treatment (5.56 vs. 4.17% overall). Skipping treatment owing to cost was more commonly reported for fourth-line treatment for patients with CML (5.00 vs. 3.48% overall).

Table 2. Patients not recommended for or who refused, discontinued, reduced, or skipped treatment due to cost; by line of therapy (Base: patients considered for treatment).

Overall, non-optimal treatment due to cost was less commonly reported by physicians treating transplant-ineligible patients with MM (1.41%) vs. CML (6.53). Only 0.35% of transplant-ineligible patients with MM refused the regimen they were recommended owing to cost. Among these patients who began treatment, 0.71% discontinued, 1.10% reduced their dose, and 0.52% skipped treatment because of treatment cost. This suggests that 2–4% of transplant-ineligible patients with MM overall receive non-optimal treatment owing to treatment cost. Differences in the effect of the cost on treatment decisions were significantly different for transplant-ineligible patients with MM for specific lines of treatment only versus for these patients overall: discontinuation of third-line treatment (1.95 vs. 0.71% overall) and skipping doses for second-line treatment (1.36 vs. 0.52% overall). A similar difference was observed for those patients in comparison to first-line therapy. Although not significantly different from overall transplant-ineligible patients with MM, non-recommendation of optimal treatment was most commonly reported for fourth-line treatment (2.15 vs. 1.41% overall), discontinuation of treatment was most commonly reported for third-line treatment (1.95 vs. 0.71% overall), and skipping of doses was more commonly reported for second-line treatment (1.36 vs. 0.52% overall).

Some statistically significant differences in behavior were also observed based on physician age and type of facility. For example, among physicians treating patients with CML, those aged 50–59 years had fewer patients in first-line treatment for whom they recommend non-optimal treatment owing to cost and those whose primary facility was a national/public hospital recommend non-optimal treatment owing to cost to more first-line patients (Supplement Table 1). Moreover, among physicians treating transplant-ineligible MM physicians 40–49 years of age had more patients in fourth-line treatment for whom they recommend non-optimal treatment owing to cost and physicians 60–79 years of age had more first- and second-line patients for whom they recommend non-optimal treatment owing to cost (Supplement Table 1). Transplant-ineligible MM physicians whose primary facility was a general hospital recommend non-optimal treatment owing to treatment cost to more fourth-line patients whereas those whose primary facility was a university hospital said they recommend non-optimal treatment owing to treatment cost to more second-line patients. Other physician characteristics were not statistically different from the overall responses for physicians who treated transplant-ineligible patients with MM.

shows the percentage of physicians who decided not to recommend optimal treatment and the percentage of their patients who refused or discontinued treatment or reduced or skipped doses, as reported by the physicians, by number of patients. Most physicians reported that cost effected the treatment decision for no (zero) patients for each decision item, suggesting that the effect of cost on treatment decisions for these patients may be limited. Regarding treatment recommendation, 21% of CML physicians and 12% of transplant-ineligible MM physicians reported recommending non-optimal treatment for ≥1 patient per year owing to treatment cost.

Attitudes concerning treatment cost

provides an overview of physician attitudes concerning treatment cost. Physicians were asked to rate on a five-point scale the degree to which they agreed or disagreed with each statement. The percentage of physicians choosing Agree or Somewhat Agree and Disagree or Somewhat Disagree are presented. Among CML physicians versus transplant-ineligible MM physicians, 59.0 and 54.7%, respectively, said that they consider the balance between drug cost and efficacy when choosing a regimen for their patients, including newly diagnosed cases, and 46.7 and 53.8% said that they consider the balance between drug cost and efficacy when choosing a regimen for later lines of treatment. On the other hand, only 21.9 and 20.8% said that they proactively reduce dose or skip treatment to reduce the treatment cost burden on patients.

Table 3. Physician attitudes concerning treatment cost.

A difference in attitudes concerning treatment cost was observed based on the percentage of physicians that disagreed with each statement. For physicians treating transplant-ineligible MM a smaller percentage of physicians disagreed with statements about its importance. That is, the attitudes of physicians treating transplant-ineligible MM suggest that treatment cost is important for them and their patients. For example, a much smaller percentage of physicians treating transplant-ineligible MM disagreed with the statement “Patients that are concerned about their cost burden when newly diagnosed are increasing” (23.6% of physicians for transplant-ineligible MM vs. 51.4% for CML). When it some to later lines of therapy, only 19.8% of physicians treating transplant-ineligible MM disagreed with the statement “I consider the balance between drug cost and efficacy when choosing a regimen for later lines of treatment” compared to 43.8% of physicians treating CML. Moreover, a much smaller percentage of physicians did not agree with the statement, “Patients that are concerned about their cost burden when choosing a regimen for later lines of treatment are increasing” (17.9% of physicians for transplant-ineligible MM vs. 50.5% for CML). Overall, this suggests that treatment cost may be a bigger concern for physicians and patients when it comes to treatment for transplant-ineligible MM even though their concern may be less likely to lead to non-optimal treatment compared to CML.

Types of patients receiving non-optimal treatment

shows the characteristics of patients whom physicians did not recommend for optimal treatment or who refused, discontinued, reduced, or skipped treatment for both conditions owing to treatment cost. Age was a bigger factor for transplant-ineligible patients with MM, with 62% of physicians saying that they recommend non-optimal treatment owing to treatment cost for patients aged ≥75 years compared with 34% of physicians treating patients in that age range with CML. Moreover, 42 versus 21% of physicians, respectively, recommend non-optimal treatment owing to cost for patients in elderly-only households. Similarly, 39% of physicians treating transplant-ineligible patients with MM recommended non-optimal treatment owing to cost for unemployed persons and pensioners, respectively, which was significantly lower than physicians overall.

Table 4. Characteristics of patients not recommended treatment or who discontinued treatment owing to treatment cost as reported by physicians; by patient characteristics.

Presence of subjective symptoms was selected as a reason for patients to undergo non-optimal treatment owing to treatment cost by 31 and 14% of physicians treating transplant-ineligible patients with MM and those treating patients with CML, respectively, and a treatment duration of 1 to <3 years was selected by 40 versus 23% of physicians. For CML physicians, 18.1% reported that they consider non-optimal treatment due to cost for those with a treatment duration of ≥5 years versus only 6.5% of transplant-ineligible MM physicians. This was even higher than responses for the treatment duration of 3 to <5 years (14.3%) for patients with CML, suggesting that longer treatment duration may be associated with non-optimal treatment due to cost for CML. Based on the Stop Imatinib (STIM) study findings, the Japanese guidelines for the treatment of hematopoietic tumors mention that some patients who have maintained a molecular response (MR) long term may maintain a MR even after discontinuing treatment with imatinib. This guidance may contribute to the decision to stop treatment of CML at later lines if the marginal benefit in terms of efficacy is thought to be limited relative to the additional cost of treatmentCitation29.

Internet use for gathering disease and treatment information was also a commonly selected factor in decisions concerning non-optimal treatment, particularly for transplant-ineligible patients with MM. Forty percent of physicians treating these patients said that non-optimal treatment is recommended for patients who do not seem to use the Internet compared with 22% of CML physicians.

Discussion

The findings of this study suggest that, while treatment cost did not lead to non-optimal treatment for many patients, 10–20% of patients with CML and 2–4% of transplant-ineligible patients with MM may undergo non-optimal treatment owing to treatment cost. In particular, treatment cost can have a considerable effect on physician recommendations of optimal treatment and adherence of patients to prescribed treatment dosing and frequency for CML. Although no significant differences from the study’s overall patient population were observed by line of therapy, non-optimal treatment recommendation due to cost was more common during later versus earlier lines of therapy, with physicians being most likely to recommend non-optimal treatment for third-line CML treatment. A higher percentage of patients skipping treatment was more commonly reported during fourth-line versus earlier treatment in CML patients.

Although the effect of treatment cost was reported to be smaller for patients with transplant-ineligible MM versus CML, physician recommendations and adherence of patients in terms of dosing were particularly affected by treatment cost. Physicians 40–49 years of age and those working in general hospitals, in particular, recommended non-optimal treatment owing to cost during fourth-line treatment. This suggests that the treatment cost for late-stage patients may be a bigger concern among mid-career physicians and those working at general hospitals. A higher percentage of transplant-ineligible patients with MM were said to discontinue or skip treatment during third- and second-line treatment, respectively, owing to cost, suggesting that cost may be a bigger issue for earlier lines of therapy for those with transplant-ineligible MM versus CML. However, the underlying cause of this difference is unclear.

Physicians not recommending optimal treatment owing to cost was the biggest factor identified. This behavior was observed for 19% of CML physicians and 12% of transplant-ineligible MM physicians. As such, this study confirms that treatment cost is a consideration for treatment selection and that it affects the treatment decisions for some patients with CML and transplant-ineligible MM, although the effect may be limited. In Japan, there were estimated to be 2,541 CML patients undergoing drug therapy in 2020, meaning that an estimated 166 patients with CML per year may be receiving non-optimal treatment owing to costCitation30. Similarly, there were estimated to be 14,386 transplant-ineligible MM patients undergoing drug therapy in 2020, meaning that an estimated 203 patients with MM per year may undergo non-optimal treatment owing to cost.

Decisions by patients to refuse, discontinue, reduce, or skip treatment owing to treatment cost can also lead to non-optimal treatment. This study found that, for CML, up to 4% of patients reduce their treatment owing to cost and 2% of patients refuse treatment as some point. Similarly, about 1% of transplant-ineligible patients with MM reduce their treatment owing to treatment cost and 1% were said to refuse treatment as some point. This suggests that, in Japan, as many as 160–320 patients with CML and 78–156 transplant-ineligible patients with MM per year may choose to undergo non-optimal treatment owing to cost.

Previous studies have shown that as many as 22% of hematology patients are dissatisfied with treatment cost, but, to our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the effect of cost on their decision-makingCitation11. Similar to treatment recommendations, a decision by the patients to refuse, discontinue, reduce, or skip treatment owing to cost was reported by some physicians. Overall, however, only 13–14% of physicians reported that the decision of one or more patient was affected by cost. This may reflect a lack of awareness or understanding about patient decisions among physicians and that they may have incomplete information regarding patient decision-making.

For both CML and transplant-ineligible patients with MM the age of the patient (very elderly) and their occupation status (unemployed persons and pensioners) were factors commonly selected as characteristics that may lead patients to ultimately undergo non-optimal treatment owing to cost, suggesting that treatment cost may disproportionately affect elderly persons and retired persons. For transplant-ineligible patients with MM, household composition (elderly-only household), duration of treatment (1 to <3 years) and lack of use of the Internet were also commonly selected as patient characteristics that might lead to non-optimal treatment owing to cost, suggesting that the nature of the condition and the need for frequent hospital visits, for example, may affect treatment decisions.

Although this study included about 8% of hematologists in Japan and is thought to cover approximately 13% of new CML cases and approximately 30% of new transplant-ineligible MM cases from about 40% of Japanese cancer-based hospitals and cancer treatment centers, this study is limited to some degree by its design. This study is a self-reported, cross-sectional online survey, and, given the nature of self-reported surveys, it is difficult to validate the reporting of physicians concerning their treatment behavior and the rationale of their patients to refuse or discontinue treatment. Moreover, the results may differ to the extent that prescribing behavior and patient behavior differ according to the age, specialty, facility, and location of physicians and the age, sex, and socioeconomic status of their patients. Although the influence of these factors was considered, the small sample size prevented a detailed examination of the influence of those factors. An intra-cluster correlation analysis might also have revealed that responses are driven by physician characteristics. However, that point was already confirmed to a degree given that non-optimal treatment decisions were driven by 10–20% of physicians overall.

Conclusion

While treatment cost did not lead to non-optimal treatment for most patients, non-optimal treatment owing to treatment cost was observed for some CML patients and transplant-ineligible patients with MM in Japan, particularly with the former. These findings suggest that although treatment cost is important to many physicians and is an increasing concern for patients, its impact on treatment decisions in Japan may be limited. Further research among physicians and patients may help identify what leads them to act (or not act) on these concerns may help to confirm the effect of treatment cost on the decisions of patients.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

The article received funding from AbbVie GK.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

TMi is a full-time employee of AbbVie GK. TMu, YH, and JS are former employees of AbbVie GK. NT and ML are full-time employees of INTAGE Healthcare Inc.

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

TMu, YH, TMi, NT, ML, and JS were involved in the overall conceptualization of the study. TMu, NT, and ML were involved in the design of the questionnaire. NT managed the data collection process. NT and ML analyzed the data with support from TMu. ML and NT were involved in the interpretation of results and the initial drafting of the manuscript. TMu, YH, TMi, and JS reviewed the draft manuscript and provided suggestions to improve it. ML and NT finalized the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Yukiko Nishimura for her advice and input on the concept of this study and Kazutake Yoshizawa, and Masahiko Nakayama for their advice and input on the study design. We also thank Yoko Yajima and Natsuko Satomi for their advice and input regarding the survey instrument development. This study was funded by AbbVie GK.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (884.8 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (57.3 KB)References

- Center for Cancer Control and Information Services, National Cancer Center. Cancer statistics in Japan. Tokyo: Center for Cancer Control and Information Services, National Cancer Center; 2018.

- Center for Cancer Control and Information Services, National Cancer Center. Cancer statistics in Japan. Tokyo: Center for Cancer Control and Information Services, National Cancer Center; 2013.

- INTAGE Healthcare. DI track. Tokyo: INTAGE Healthcare Inc.; 2019.

- IQVIA. IQVIA pharmaceutical market statistics sales data period: 1989–2018 (in Japanese). Tokyo: IQVIA; 2019.

- IQVIA. IQVIA pharmaceutical market statistics sales data period: January – December, 2019 (in Japanese). Tokyo: IQVIA; 2020.

- Economic and Social Research Institute. Annual report on national accounts of 2019 (in Japanese). Tokyo: Economic and Social Research Institute; 2019.

- Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare. Overview of medical service regime in Japan. Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare; 2021.

- Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare. Overview for those using high cost medical care (in Japanese). Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare; 2018.

- Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare. Survey on the salary structure – report summary of year 2017 (in Japanese). Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare; 2017.

- Koinuma N. Proposal for the breakdown of increased cancer healthcare cost and its improvement. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2013;43(4):552–356.

- INTAGE Healthcare Inc. Patient mindscape (APM) survey. Tokyo: INTAGE Healthcare Inc.; 2019.

- Shiroiwa T, Tsutani K. Research on inclusion of health economics in treatment guidelines (in Japanese). Tokyo (Japan): Health Labor Sciences Research Grant, Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare; 2016.

- Bolt T, Mahlich J, Nakamura Y, et al. Hematologists' preferences for first-line therapy characteristics for multiple myeloma in Japan: attribute rating and discrete choice experiment. Clin Ther. 2018;40(2):296–308.

- Arikian SR, Milentijevic D, Binder G, et al. Patterns of total cost and economic consequences of progression for patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Curr Med Res Opin. 2015;31(6):1105–1115.

- Laudicella M, Walsh B, Burns E, et al. Cost of care for cancer patients in England: evidence from population-based patient-level data. Br J Cancer. 2016;114(11):1286–1292.

- Serra-Arbeloa P, Rabines-Juarez AO, Alvarez-Ruiz MS, et al. Cost of cutaneous melanoma by tumor stage: a descriptive analysis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108(3):229–236.

- Sun L, Legood R, Dos-Santos-Silva I, et al. Global treatment costs of breast cancer by stage: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0207993.

- Ward RL, Laaksonen MA, van Gool K, et al. Cost of cancer care for patients undergoing chemotherapy: the elements of cancer care study. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2015;11(2):178–186.

- Dranitsaris G, Zhu X, Adunlin G, et al. Cost effectiveness vs. affordability in the age of immuno-oncology cancer drugs. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2018;18(4):351–357.

- Kawamura M, Takao H, Okumura M, et al. Review of colorectal cancer cases based on their route of detection (in Japanese). Ningen Dock. 2015;30:616–622.

- KEGG Medicus. Dexamethasone listing. Kyoto: KEGG Medicus.

- KEGG Medicus. Lenalidomide listing. Kyoto: KEGG Medicus.

- KEGG Medicus. Daratumumab listing. Kyoto: KEGG Medicus.

- KEGG Medicus. Dasatinib Listing. Kyoto: KEGG Medicus.

- Bristol Meyers Squibb KK. Sprycel 20mg/50mg usage survey report. Tokyo: Bristol Meyers Squibb KK; 2015.

- Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare. 2018 Physician survey report. Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare; 2018.

- Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare. 2018 Survey of medical institutions report. Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare; 2018.

- Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare. Cancer base hospital listing. Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare; 2018.

- Usui N. JSH guideline for tumors of hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues-lukemia: 4. Chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML)/myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN). Int J Hematol. 2017;106(5):591–611.

- CancerMPact®. 2020 [cited 2020 Apr 24]. Available from: Cerner EnvizaSM/Synix Inc.: synix.co.jp/cancermpact (Unauthorized reproduction prohibited).