Abstract

Background and objective

Sintilimab is a selective PD-1 inhibitor with efficacy in advanced or metastatic nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients. This study evaluated the cost-effectiveness of sintilimab + chemotherapy versus camrelizumab + chemotherapy as the first-line treatment for locally advanced or metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC in Chinese patients. In addition, this study aimed to reveal the impact of the reference treatment choice on the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) results.

Methods

A partitioned survival model (PSM) with three health states was constructed in a 3-week cycle with a lifetime horizon from the Chinese healthcare system perspective. Anchored matching adjusted indirect comparison was used for survival analyses based on individual patient data from Orient-11. Sintilimab + chemotherapy was chosen as the reference treatments in scenarios 1 and 2, while the camrelizumab + chemotherapy was chosen as the reference treatments in scenario 3. The utility values of different health states were derived from the patient-level European Organization for Research and Treatment Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) scores by mapping to the EQ-5D-5L, and QALYs were calculated as the health outcomes. One-way deterministic sensitivity analysis (DSA) and probability sensitivity analysis (PSA) were performed to explore model uncertainty.

Results

Compared to camrelizumab + chemotherapy, sintilimab + chemotherapy was associated with higher effectiveness (incremental QALYs ranged from 0.13–0.62) and lower total costs (incremental costs ranged from $1,099–$5,201), resulting in an ICER ranging from $6,440–$8,454/QALY.

Conclusions

Sintilimab + chemotherapy is a cost-effective option compared with camrelizumab + chemotherapy as the first-line treatment for locally advanced or metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC in China.

Introduction

Lung cancer has become the second most commonly diagnosed cancer and causes the most cancer-related deaths globallyCitation1. According to the World Health Organization, the incidence and mortality of lung cancer ranked first in China, accounting for 17.9% and 23.8% of all cancers, respectivelyCitation2. Lung cancer also led to 36.4 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) worldwide in 2016 (approximately 1.5% of all-cause DALYs), placing a major disease burden on societyCitation3.

Among all diagnosed lung cancer cases, approximately 85% are non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC)Citation4. NSCLC can be divided into two histological subtypes: squamous NSCLC and nonsquamous NSCLC. Nonsquamous NSCLC is the major subtype of NSCLC, representing 70–75% of all casesCitation5. Patients with gene mutations usually respond to targeted therapy, while those without gene mutations may need immunotherapy to improve their 5-year survival rate. The Guidelines of the Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology (CSCO) for Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Clinical Practice 2021Citation6 recommended four therapies for advanced gene mutation-negative nonsquamous NSCLC as follows: (1) pembrolizumab monotherapy (programmed cell death-1 tumor proportion score [PD-L1 TPS] ≥ 50%); (2) pembrolizumab plus pemetrexed and platinum-based chemotherapy; (3) camrelizumab plus pemetrexed and platinum-based chemotherapy; and (4) sintilimab plus pemetrexed and platinum-based chemotherapy.

Sintilimab is a selective anti-PD-1 antibody that inhibits interactions between PD-1 and its ligand, PD-L1. Compared with pembrolizumab or nivolumab, sintilimab has a different binding site and potentially greater affinity against PD-1 based on preclinical dataCitation7. In February 2021, sintilimab plus pemetrexed and platinum was licensed by the National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) as the first-line treatment for patients with EGFR and ALK mutation-negative advanced or metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC based on the results of the corresponding clinical trial Orient-11. It was also accepted by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for reviewCitation8.

The randomized, double-blind, phase 3 study Orient-11 (NCT 03607539) was conducted to compare the safety and efficacy between sintilimab plus chemotherapy and placebo plus chemotherapy treatment in Chinese patients with locally advanced or metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC. The clinical trial was taken in the Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Center in China. According to the interim analysis (by 15 November 2019) of Orient-11Citation7, the sintilimab plus chemotherapy group had significantly prolonged progression-free survival (PFS) compared with the placebo plus chemotherapy group in the target population (8.9 months versus 5.0 months). Recently, updated overall survival (OS) dataCitation9 demonstrated that, as of January 2021, the median OS of the sintilimab plus chemotherapy group was superior to that of the placebo plus chemotherapy group (not reached versus 16.8 months).

Sintilimab plus chemotherapy is also strongly recommended in the clinic, but its cost-effectiveness has not been assessed in China. The China Guidelines for Pharmacoeconomic Evaluations 2020Citation10 recommended that the selection of a comparator should prioritize standard treatment for the same indication. Camrelizumab plus chemotherapy is currently the standard treatment for patients with locally advanced or metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC in China. In addition, camrelizumab plus chemotherapy was included in the National Medical Insurance Drug List in the 2020 China Medical Insurance Negotiations in December 2020. However, the cost-effectiveness of sintilimab plus chemotherapy versus camrelizumab plus chemotherapy has not been examined. Therefore, this study has two objectives: (1) compare the cost-effectiveness of sintilimab plus chemotherapy and camrelizumab plus chemotherapy for the first-line treatment of locally advanced or metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC in China and (2) reveal the impact of the reference treatment choice on the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) results.

Methods

Model structure

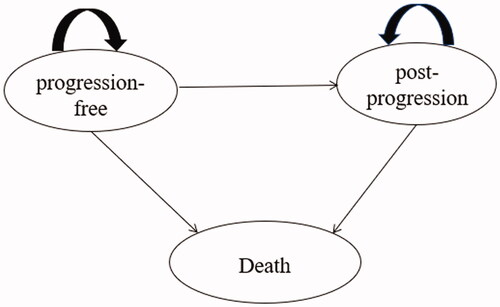

The model was developed in Microsoft Excel and structured as a partitioned survival model (PSM) (), the most frequently used approach in the economic evaluation of cancer treatments according to a review of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) appraisalsCitation11. One published study proved that the Markov model and PSM can obtain similar results under the same model structure and assumptions, but it is relatively easy to construct the PSM when individual data are availableCitation12. Additionally, PSM was also preferred for the economic evaluation of interventions for chronic disease with limited health status in NICE DSU TECHNICAL SUPPORT DOCUMENT 19 and the China Guidelines for Pharmacoeconomic Evaluations 2020Citation10,Citation11.

Therefore, PSM was used to estimate the outcomes and costs of nonsquamous NSCLC patients with three mutually exclusive health states: progression-free (PF), postprogression (PP), and death. The proportion of patients in each health state over time could be calculated from the OS curve and the PFS curve. The PF state was defined as the initial state of patients until progression or death, and patients in this state were assumed to have treatment-related costs, involving drug costs, follow-up costs, administration costs, and management costs of grade 3/4 adverse events (AEs). Patients who experienced disease progression were categorized in the PP state, and the definition of progression was consistent with the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) in Orient-11. Within the PP state, costs associated with medical management and the costs of subsequent treatments would occur. It was assumed that the proportion of different subsequent therapy options was aligned with the trial data of Orient-11; therefore, the costs that occurred were weighted by the observed proportion. If patients died, the cost of end-of-life care was calculated. Patients who stayed in the PP state experienced a lower utility weighting than those in the PF state, and the utility of the death state was specified as 0.

The following outcomes were measured in this model: quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), life-years gained (LYGs), and costs. Each model cycle represented 21 days (3 weeks), which was aligned with the administration cycle of the drugs in Orient-11, and the time horizon was lifetime. Only direct medical costs were assessed in the model from the Chinese healthcare system perspective. Analyses were based on 2020 or 2021 prices, and a discount rate of 5% was applied for both costs and benefits according to the China Guidelines for Pharmacoeconomic Evaluations 2020Citation10. All costs have been converted into US dollars, and the exchange rate was 1 US dollar = 6.366 Chinese RMB Yuan (US Dollar to Chinese Yuan Renminbi conversion – Last updated 26 March 2022, 11:35 UTC). The willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold of 1–3-times the GDP per capita in China ($12,718–$38,154 per QALY gained in 2021) was adopted for the analysis of cost-effectiveness according to the recommendation of the China Guidelines for Pharmacoeconomic Evaluations 2020Citation10.

Patient population

The trial design, efficiency, and safety details of Orient-11 and CameL can be obtained from the published literatureCitation7,Citation13. In addition, the individual patient data (IPD) of Orient-11 were provided by Innovent Biologics. The multicenter, open-label, phase 3 study CameL was designed to assess the efficacy and safety of camrelizumab plus chemotherapy as a first-line treatment for nonsquamous NSCLC in China. The target patient population of the model was based on the trial eligibility criteria of Orient-11 and CameL: (1) patients with histologically or cytologically confirmed stage IIIB–IV nonsquamous NSCLC; (2) ineligible for radical surgery or radiotherapy; (3) without EGFR and ALK alteration; and (4) no previous systemic treatment for advanced or metastatic disease. Patients in the intervention groups received four cycles of cisplatin (75 mg/m2) or carboplatin (area under curve 5 mg/mL per min) plus pemetrexed (500 mg/m2) with sintilimab (200 mg) every 3 weeks. Patients in the comparator groups received four cycles of carboplatin (area under curve 5 mg/mL per min) plus pemetrexed (500 mg/m2) with camrelizumab (200 mg) every 3 weeks.

Model inputs

Anchored matching adjusted indirect comparison (MAIC)

Since there is no head-to-head comparison of sintilimab plus chemotherapy versus camrelizumab plus chemotherapy, considering that the IPD of Orient-11 can be obtained and the efficiency of placebo plus chemotherapy was evaluated in both trials, the anchored MAIC method was adopted in the model. The IPD of the Orient-11 were used to align the patient’s baseline characteristics with the CameL trial and the characteristics in the two groups after adjustment are shown in Supplementary Table S1. The population difference between Orient-11 and CameL and results of the PFS and OS HRs are shown in . All baseline characteristics were incorporated in the adjustment as detailed in the CameL trial except for PD-L1, which was a prognostic factor and should not be included in the MAIC according to the NICE DSU TECHNICAL SUPPORT DOCUMENT 18. All MAIC methods have a strong assumption that prognostic factors or treatment effect modifiers are the same in the two populations.

Table 1. Population difference between Orient-11 versus CameL and MAIC results.

For anchored comparisons, the choice of reference treatment can potentially impact the analysis results. Three scenarios choosing sintilimab plus chemotherapy (scenario 1 and 2) or camrelizumab plus chemotherapy (scenario 3) as the reference treatment were analyzed.

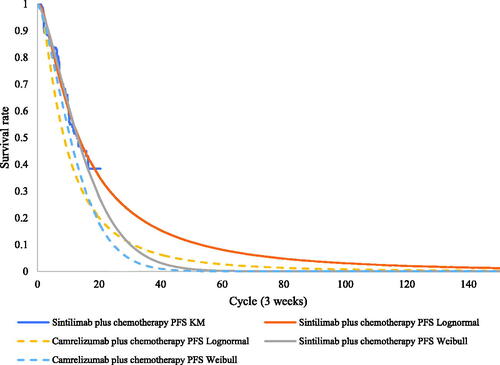

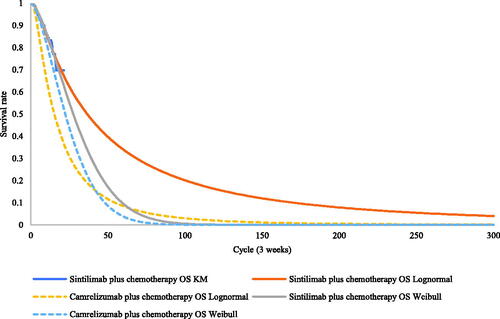

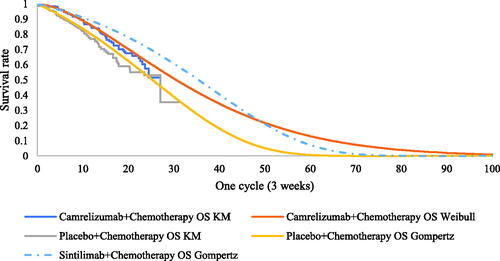

Efficiency data in scenario 1 and 2

Efficiency data for sintilimab plus chemotherapy and placebo plus chemotherapy were obtained from the Orient-11 IPD supported by Innovent Biologics. Parametric distributions, including the Weibull, log-normal, log-logistic, exponential, and Gompertz distributions, were used to extrapolate survival outcomes to the lifetime horizon. The goodness of fit of distributions was evaluated according to visual inspection and statistical testing (Akaike information criterion and Bayesian information criterion). The best-fitting parametric distributions for the PFS and OS data of sintilimab plus chemotherapy were log-normal distributions. For the unmature data, especially in the OS, the Weibull models were used in scenario 2 to explore the impact brought by difference survival models. The exploration and fitting of PFS and OS are shown in and and Supplementary Figures S1 and S2. Testing results of the fitting are shown in the Supplementary Tables S2 and S3. The median PFS and OS of the sintilimab plus chemotherapy fitting curves were 9.3 and 23.0 months, which were consistent with the actual survival curves (mPFS = 9.2 months and mOS = 22.9 months).

Notably, scenarios 1 and 2 used the HRs of camrelizumab plus chemotherapy versus placebo plus chemotherapy, which relaxed the assumption of proportionality of hazards in the OS of camrelizumab plus chemotherapy in the CameL trial. (Test results of the PH assumption and fitting are shown in Supplementary Figures S3, S4, S7, and S8 and Tables S4–S6.)

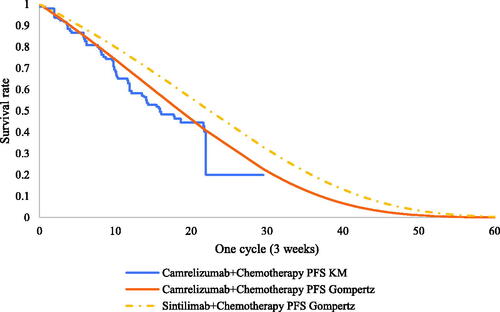

Efficiency data in scenario 3

Efficiency data for camrelizumab plus chemotherapy and placebo plus chemotherapy were obtained from the CameL study. PFS and OS information for CameL patients were extracted from published Kaplan-Meier survival curves by using Engauge Digitizer software 2.0. The algorithm published by Guyot et al.Citation14 was used to reconstruct IPD, and the same five parametric distributions described in scenario 1 were used to extrapolate survival outcomes to the lifetime horizon. The best-fitting parametric distributions for the PFS and OS data of camrelizumab plus chemotherapy were Gompertz and log-logistic distributions, respectively, and the Gompertz distribution was also the most appropriate for the OS of placebo plus chemotherapy in CameL (test results of the fitting are shown in Supplementary Tables S2–S4). The exploration and fitting of PFS and OS are shown in and and Supplementary Figures S9–S11.

Under the proportional hazards (PH) assumption, camrelizumab plus chemotherapy and placebo plus chemotherapy were chosen as the reference treatments to fit the PFS and OS data of sintilimab plus chemotherapy using MAIC-adjusted HR (sintilimab plus chemotherapy versus placebo plus chemotherapy). The PFS and OS of Orient-11 patients and the PFS of CameL patients all satisfied the PH assumption; therefore, the PFS of the camrelizumab arm and the OS of the placebo arm were chosen as the reference treatments (the testing results of the PH assumption are shown in Supplementary Figures S5–S8).

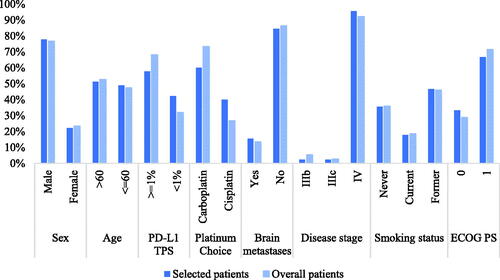

Utility weights

According to the NICE DSU Technical Support Document 10Citation15, mapping should be considered at best a second-best solution to directly collected EuroQol-5-dimension (EQ-5D) values. Due to the lack of EQ-5D data in both clinical trials, utility values were derived from the patient-level European Organization for Research and Treatment Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) scores in Orient-11 by mapping to the EQ-5D-5L. The mapping algorithm was based on the published paper by Khan et al.Citation16. The 45 patients whose PF utility was larger than their PP utility were enrolled in the analyses. The characteristics of the selected patients are shown in and were compared with those of the overall patients in the clinical trial. The utility value was 0.75 for the PF health state, 0.59 for the PP health state, and zero for death. The utility values were applied both in the sintilimab arm and the camrelizumab arm, and disutilities of AEs (incidence ≥ 5%, grade 3 or 4) were calculated according to the difference in the incidence of AEs between the two arms.

Resource use and costs

From the perspective of the Chinese healthcare system, only direct medical costs were estimated, including treatment costs, costs of AE management, costs of subsequent treatment, costs of disease management, follow-up costs, and end-of-life care costs. Treatment costs consisted of the costs of sintilimab, camrelizumab, and chemotherapy and were calculated by the dosing schedules in the clinical trials and the unit costs of the drugs. The costs of AE management were estimated according to the treatment of AEs, the duration of AEs, and the incidence of AEs. Only grade 3 or 4 AEs occurring in ≥5% of patients in Orient-11 and CameL, as well as expert opinions, were included. Costs of subsequent treatment in the sintilimab arm were based on the individual patient data from Orient-11 and were weighted by the proportion of patients receiving the corresponding subsequent treatment (subsequent treatments are shown in Supplementary Table S7). Costs of subsequent treatment in the camrelizumab arm were assumed to be the same as those in the sintilimab arm since sintilimab and camrelizumab are both same-line immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) treatments in the clinic. Costs of disease management included the costs of diagnosis, intravenous administration, nursing, and hospital stay. Follow-up costs were divided into four parts according to the clinical design of Orient-11, including the computed tomography, blood chemistry, routine blood tests, and routine urine tests. The end-of-life care costs represented the resources used when patients were dying and were derived from the published literatureCitation17.

The drug costs of treatment and AE management were based on the median price of the winning bid product derived from the China Drug Bidding Database (shuju.menet.com.cn). The unit costs of disease management and follow-up were from the healthcare documents and expert opinion.

To estimate the dosages of pemetrexed in the sintilimab arm and the camrelizumab arm, we assumed that the mean weight of patients was 65 kg and the mean body surface area was 1.6 m2 according to the recommendation from the NMPA in China. All patients were assumed to receive sintilimab plus chemotherapy or camrelizumab plus chemotherapy at the PF state for up to 2 years or until disease progression. All cost parameters are listed in .

Table 2. Cost and utility parameters in the model.

Sensitivity analyses

A deterministic sensitivity analysis (DSA) and probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) were conducted to assess the uncertainty in the model. In the one-way DSA, key parameters were varied by the standard error, 95% confidence interval, or ±20% of the deterministic value based on the data availability. Specifically, the price of sintilimab and camrelizumab was varied from 80–100% of the deterministic value because, in China, there is little space for pharmaceutical manufacturers to increase the price of drugs. The following key parameters were included in the one-way DSA: discount rate (varied from 0–8%), costs (drug acquisition, disease management, follow-up, subsequent treatment, and end-of-life care, varied by the standard error, 95% confidence interval, or ±20%), incidence and duration of AEs (varied by ±20%), utilities and disutilities (varied by 95% confidence interval). In the PSA, the parametric distribution assumptions were based on the recommended guidelines in Decision Modelling for Health Economic EvaluationCitation22, where cost parameters and hazard ratios obeyed the gamma distribution, the incidence of AEs and utility parameters obeyed the beta distribution, and values of HR obeyed the gamma distribution. It should be noted that Cholesky decomposition was also used in the PSA to take into account the correlation between parametersCitation22. A 5,000s-order Monte Carlo simulation was performed in the PSA. The parameters included in the one-way DSA and the PSA and their variations are listed in Supplementary Table S10.

Results

Base case analysis

The costs and health outcomes summarized in were stratified by the scenarios and arms. Compared with camrelizumab plus chemotherapy, sintilimab plus chemotherapy gained additional QALYs ranging from 0.13–0.61. Incremental costs ranged from $1,099–$5,201. Consequently, the ICERs of the base case ranged from $6,440–$8,454/QALY. At a willingness-to-pay threshold of 1–3 GDP per capita in China, sintilimab plus chemotherapy was more cost-effective than camrelizumab plus chemotherapy as the first-line treatment for locally advanced or metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC. The PFS and OS modeled plots of three scenarios are shown in Supplementary Figures S12–S14 to give a clear visual of the relative LY gain in PF and PP.

Table 3. Summary of the cost and health outcomes results.

Sensitivity analyses

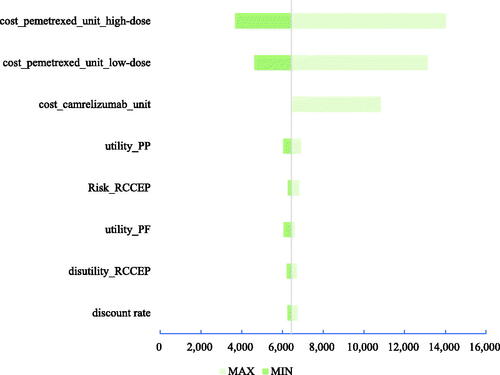

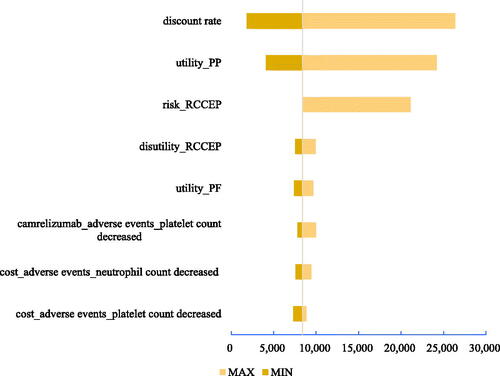

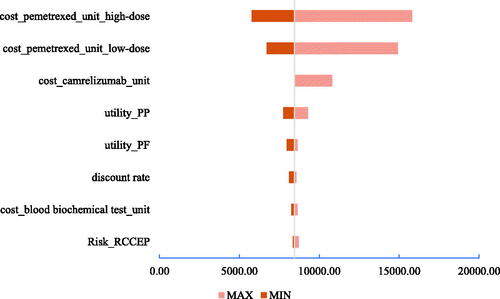

Deterministic sensitivity analyses

Three tornado diagrams of the top eight most influential key parameters in the three scenarios are presented in . According to both DSA results, the unit costs of high-dose and low-dose pemetrexed, the unit cost of camrelizumab, and utility of PP were the main driving parameters in scenarios 1 and 2. The discount rate, utility of PP, risk of reactive cutaneous capillary endothelial proliferation (RCCEP), and disutility of RCCEP were the main driving parameters in scenario 3. The ICUR results from the one-way DSA suggested the stable result that the sintilimab plus chemotherapy would always cbe ost-effective compared with camrelizumab plus chemotherapy.

Figure 7. Tornado diagram in scenario 1. Abbreviations. PF, progression-free; PP, postprogression; ICUR, incremental cost utility ratio.

Probabilistic sensitivity analyses

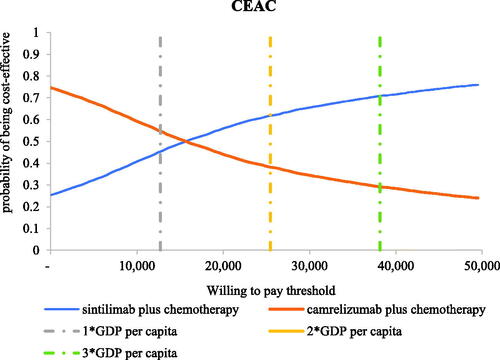

In scenario 1, the results of the 5,000 Monte Carlo simulations showed an average QALY gain of 0.63 and an incremental cost of $5,908, resulting in a probabilistic ICUR of $9,387/QALY, which is lower than the WTP threshold. According to the cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CECA) in , the likelihood of sintilimab plus chemotherapy being cost-effective was 66.72–90.28% under the WTP threshold of $12,718–$38,154 per QALY.

Figure 10. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves in scenario 1. Abbreviations. CEAC, cost-effectiveness acceptability curve; WTP, willingness-to-pay; GDP, gross domestic product.

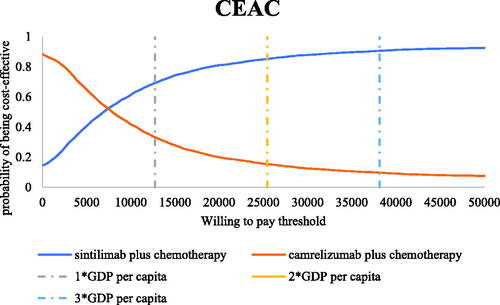

In scenario 2, the results of the 5,000 Monte Carlo simulations showed an average QALY gain of 0.28 and an incremental cost of $1,741, resulting in a probabilistic ICUR of $6,110/QALY, which is lower than the WTP threshold. According to the cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CECA) in , the likelihood of sintilimab plus chemotherapy being cost-effective was 73.34–91.06% under the WTP threshold of $12,718–$38,154 per QALY.

Figure 11. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves in scenario 2. Abbreviations. CEAC, cost-effectiveness acceptability curve; WTP: willingness-to-pay; GDP: gross domestic product.

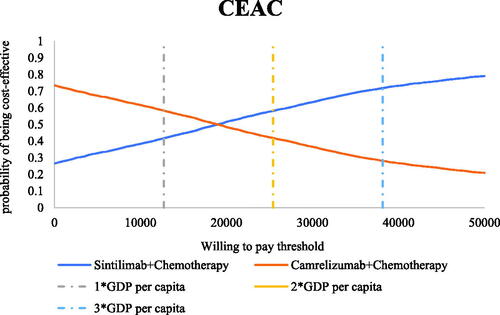

In scenario 3, the results of the 5,000 Monte Carlo simulations showed an average QALY gain of 0.20 and an incremental cost of $3,769, resulting in a probabilistic ICUR of $18,974/QALY, which is lower than the WTP threshold. According to the cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CECA) in , the likelihood of sintilimab plus chemotherapy being cost-effective was 45.22–70.82% under the WTP threshold of $12,718–$38,154 per QALY.

Discussion

This study evaluated the cost-effectiveness of sintilimab plus chemotherapy versus camrelizumab plus chemotherapy in patients with locally advanced and metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC from a Chinese healthcare system perspective based on the IPD from Orient-11, which was weighted to balance the reported characteristics of patients in CameL using MAIC. The base case results and the CEACs implied that sintilimab plus chemotherapy was cost-effective versus camrelizumab plus chemotherapy. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to compare the cost-effectiveness of sintilimab plus chemotherapy versus camrelizumab plus chemotherapy in China.

This study is important and instructive because it emphasizes some issues that should be considered when using anchored indirect comparison methods, especially the choice of the reference treatment. PH assumption is an important consideration in choosing a reference treatment. Only a few studies considered the PH assumption when using the anchored MAIC method. In the study of Delea et al.Citation23, four arms from two clinical trials (TOWER and INO-VATE-ALL) were designed as reference treatments when applying the anchored MAIC method, and the authors mentioned that the use of the anchored MAIC method was based on the PH assumption, but they did not elaborate on the PH hypothesis test for the two trials of TOWER and INO-VATE-ALL. In fact, the PFS and OS curves of TOWER and INO-VATE-ALL could not be used to intuitively judge whether PFS and OS might meet the PH assumption; thus, the discussion on the four arms as treatment arms might be meaningful. However, in the CEAs of oncology drugs, the choice of reference treatment under the premise of not satisfying the PH assumption may lead to a larger gap in efficiency after extrapolation, such as in scenarios 1 and 2. In addition, accession of individual patient data is also a key point and is related to the selection of efficiency and utility. For example, in scenario 3, for the lack of the IPD in the CameL study, the efficiency of camrelizumab plus chemotherapy was derived from the reconstructed IPD, and the utilities had to be assumed to be the same in the sintilimab plus chemotherapy group, which also potentially impacted the results. Therefore, in this study, three different scenarios were meaningful, and each had advantages and disadvantages. In addition, the study implied an interesting phenomenon that, although the DSA in three scenarios was obviously different, the base case and PSA results were highly similar, which led to the robustness of the conclusion.

In addition, the HRs of PFS and OS in the sintilimab plus chemotherapy group before and after the MAIC method adjustment were not very different. The reason might be due to the small heterogeneity of the patient populations in Orient-11 and CameL, which might imply that the patient population of locally advanced and metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC was relatively limited. In this situation, even the use of naive indirect comparison (extracting survival data of target interventions directly from two clinical studies for comparison without adjustments for patient baseline characteristics) may not have a great impact on the final result, which is consistent with the conclusions of previous studiesCitation24.

The base case PFS and OS HRs of sintilimab plus chemotherapy after adjustment by the MAIC method were both higher than those of camrelizumab plus chemotherapy, but the confidence intervals of the two groups were large, which indicated that the difference between the effects was not obvious. The HR was also included in the PSA for analysis, and the results showed that, after 5,000 Monte Carlo simulations, the average difference in QALYs in the lifetime horizon was 0.2, which meant that the efficacy of sintilimab plus chemotherapy was slightly better than that of camrelizumab plus chemotherapy. Therefore, costs would be the main driver in determining the conclusion, which was also verified in the DSA tornado diagram, especially in scenarios 1 and 2. In addition, it should be mentioned that camrelizumab has a serious adverse event, RCCEP. According to relevant literatureCitation25, this symptom is different from a rash and has a high incidence, so it may incur great disutility for patients. According to experts’ opinions, the incidence of RCCEP in the real world is much higher than that in the CameL trial. However, due to the lack of relevant studies on the disutility of RCCEP and long-term follow-up real-world evidence, this study still estimated the incidence of RCCEP based on the expert opinions, which might underestimate the cost-effectiveness of sintilimab plus chemotherapy to some extent.

Several limitations should also be noted. First, the utility mapping algorithm used in the study was based on the British population, which may introduce bias. However, because PF and PP utilities were not the main drivers in the analyses, they might not have a great impact on the conclusion. Second, the crossover problem regarding the OS of the Orient-11 and CameL studies was not considered in this study. In Orient-11, 31.3% of patients in the placebo-combination group were crossed over to sintilimab monotherapy during the study after confirmed disease progression, and 4.6% of patients had received immunotherapy outside of the study, resulting in an effective crossover rate of 35.9%Citation7. In CameL, 38% of patients in the chemotherapy alone group crossed over to receive camrelizumab monotherapy, and an additional 4% of patients received other anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibodies, either alone or combined with other therapies, after the end of study treatmentCitation13. However, because the two-stage method adjustment results were not published in the CameL trialCitation26,Citation27, the two-stage method was also not applied in the sintilimab arm to avoid underestimation of the OS treatment effect in the camrelizumab arm.

Conclusions

According to the base analysis and the sensitivity analyses, sintilimab plus chemotherapy is cost-effective compared with camrelizumab plus chemotherapy at the WTP threshold of 1–3-times the GDP per capita in China as the first-line treatment for locally advanced or metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC patients from the perspective of the Chinese healthcare system.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Support for this study was provided by Innovent Biologics (Suzhou) Co., Ltd., Suzhou, Jiangsu, China. The authors were responsible for all content and editorial decisions, and they received no honoraria related to the development of this publication.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

MR, ZF, YW, XZ, AM, and HL have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article. HS is an employee of Innovent Biologics (Suzhou). HS did not receive direct payment as a result of this work outside of his normal salary payments.

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

MR: Study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation of results, writing of draft and final manuscript. ZF: Data collection, data analysis, interpretation of results, writing of draft and final manuscript. YW: Study design, data analysis, writing of draft and final manuscript. XZ: data collection, writing of draft and final manuscript. AM: Interpretation of results, final manuscript. HS: Study design, data analysis, interpretation of results, final manuscript. HL: Study design, interpretation of results, writing of draft and final manuscript. All authors contributed to the drafting and revision of the manuscript, and approved it for submission. HL is the principal investigator and will act as total guarantor for the study.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (995.5 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank American Journal Experts for providing English language, grammar, punctuation, spelling, and overall style editing.

Data availability statement

The authors declare that all input data to parameterize the decision analytic model are available within the article and the Supplementary Material.

References

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA A Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):618–249.

- Organization WH. The Global Cancer Observatory. 2021. Accessed 29/9, 2021.

- Hay SI, Abajobir AA, Abate KH, et al. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 333 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. The Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1260–1344.

- Kim Y-J, Oremus M, Chen HH, et al. Cost-Effectiveness analysis of afatinib, erlotinib, and gefitinib as First-Line treatments for EGFR Mutation-Positive Non-Small-Cell lung cancer in Ontario, Canada. Pharmacoeconomics. 2021;39(5):537–548.

- Chouaid C, Bensimon L, Clay E, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of pembrolizumab versus standard-of-care chemotherapy for first-line treatment of PD-L1 positive (>50%) metastatic squamous and non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer in France. Lung Cancer. 2019;127:44–52.

- ONCOLOGY CSOC. Guidelines of chinese society of clinical oncology (csco) for immune checkpoint inhibitor clinical practice 2021. People 's medical Publishing House; 2021.

- Yang Y, Wang Z, Fang J, et al. Efficacy and safety of sintilimab plus pemetrexed and platinum as First-Line treatment for locally advanced or metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC: a randomized, Double-Blind, phase 3 study (oncology pRogram by InnovENT anti-PD-1-11). J Thorac Onco. 2020;15(10):1636–1646.

- Innovent Biologics I. U.S. FDA Accepts Regulatory Submission for Sintilimab in Combination with Pemetrexed and Platinum Chemotherapy for the First-Line Treatment of People with Nonsquamous Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. 2021. Accessed 10/27, 2021.

- Yang Y, Sun J, Wang Z, et al. Updated overall survival data and predictive biomarkers of sintilimab plus pemetrexed and platinum as First-Line treatment for locally advanced or metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC in the phase 3 ORIENT-11 study. J Thorac Onco. 2021;16(12):2109–2120.10.

- Liu G, Wu J, Wu J, et al. China guidelines for pharmacoeconomic evaluations 2020. Beijing: China Market Press; 2020.

- Woods B, Sideris E, Palmer S, et al. NICE DSU technical support document 19: partitioned survival analysis for decision modelling in health care: a critical review. 2017. Available from: http://www.nicedsu.org.uk

- Rui M, Wang Y, Fei Z, et al. Will the markov model and partitioned survival model lead to different results? A review of recent economic evidence of cancer treatments. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2021;21(3):373–380.

- Zhou C, Chen G, Huang Y, et al. Camrelizumab plus carboplatin and pemetrexed versus chemotherapy alone in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (CameL): a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(3):305–314.

- Guyot P, Ades AE, Ouwens MJNM, et al. Enhanced secondary analysis of survival data: reconstructing the data from published Kaplan-Meier survival curves. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12(1):9.

- Longworth L, Rowen D. NICE DSU technical support document 10: the use of mapping methods to estimate health state utility values. 2011. Available from: http://www.nicedsu.org.uk

- Khan I, Morris S, Pashayan N, et al. Comparing the mapping between EQ-5D-5L, EQ-5D-3L and the EORTC-QLQ-C30 in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14(1):60.

- Rui M, Li H. Cost-effectiveness of osimertinib vs docetaxel-bevacizumab in third-line treatment in EGFR T790M resistance mutation advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer in China. Clin Ther. 2020;42(11):2159–2170. e2156.

- Nafees B, Lloyd AJ, Dewilde S, et al. Health state utilities in non-small cell lung cancer: an international study. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2017;13(5):e195–e203.

- Tolley K, Goad C, Yi Y, et al. Utility elicitation study in the UK general public for late-stage chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Eur J Health Econ. 2013;14(5):749–759.

- Wan X, Luo X, Tan C, et al. First-line atezolizumab in addition to bevacizumab plus chemotherapy for metastatic, nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer: a United States-based cost-effectiveness analysis. Cancer. 2019;125(20):3526–3534.

- Wehler M-S-S-ke. A health state utility model estimating the impact of ivosidenib on quality of life in patients with relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia. EHA Library. 2018;22(6):567–576.

- Briggs A, Sculpher M, Claxton K. Decision modelling for health economic evaluation. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006.

- Delea TE, Zhang X, Amdahl J, et al. Cost effectiveness of blinatumomab versus inotuzumab ozogamicin in adult patients with relapsed or refractory B-Cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia in the United States. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019;37(9):1177–1193.

- Galve-Calvo E, González-Haba E, Gostkorzewicz J, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of ribociclib versus palbociclib in the first-line treatment of HR+/HER2- advanced or metastatic breast cancer in Spain. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2018;10:773–790.

- Wang F, Qin S, Sun X, et al. Reactive cutaneous capillary endothelial proliferation in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with camrelizumab: data derived from a multicenter phase 2 trial. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13(1):47.

- Latimer NR, Abrams KR, Lambert PC, et al. Adjusting for treatment switching in randomised controlled trials – A simulation study and a simplified two-stage method. Stat Methods Med Res. 2017;26(2):724–751.

- Latimer NR, Abrams KR, Siebert U. Two-stage estimation to adjust for treatment switching in randomised trials: a simulation study investigating the use of inverse probability weighting instead of re-censoring. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19(1):69.