Abstract

Aims

To quantify healthcare resource utilization (HRU) and costs by disease stage in individuals with Huntington’s disease (HD) in a US population.

Materials and methods

This retrospective cohort study used administrative claims data from the IBM MarketScan Commercial, Multi-State Medicaid, and Medicare Supplemental Databases between 1 January 2009 and 31 December 2018. Individuals with an HD claim between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2017 were selected. Index date was the date of first HD diagnosis. Individuals were required to have continuous enrollment for ≥ 12 months pre-index, 3 months post-index, and have no pre-index HD claims. All-cause HRU and costs per patient per month (PPPM) (overall and stratified by disease stage) were assessed for individuals with HD.

Results

A total of 2,669 individuals with HD were identified. Of these, 1,432 (53.7%), 689 (25.8%), and 548 (20.5%) had early-, middle-, and late-stage HD at baseline, respectively. Mean HRU PPPM by post-index HD stage increased with disease stage for outpatient visits, pharmacy claims, and HD-related pharmacy claims (p < 0.05 for all). Mean inpatient visits and emergency room visits PPPM were highest in individuals with middle-stage HD (p <0.05 for all). Mean total all-cause healthcare cost PPPM for individuals with HD was $2,889, and it was significantly higher in middle-stage individuals, at $7,988, compared with early- and late-stage individuals, at $3,726 and $5,125, respectively; p <0.0001.

Limitations

In the absence of disease staging information in administrative claims data, staging was based on the presence of clinical markers in claims. Our evaluations didn’t include the indirect costs of HD, which may be substantial as HD typically affects people at their peak earning potential.

Conclusions

HRU and costs of care are high among individuals with HD, particularly among those with middle- and late-stage disease. This indicates that the disease burden in HD increases with disease stage, highlighting the need for interventions that can slow or prevent disease progression.

Introduction

Huntington’s disease (HD) is a rare, genetic, neurodegenerative, and ultimately fatal disease that has a devastating impact on families across generationsCitation1,Citation2. The incidence of HD is estimated to be 0.47–0.69 new cases per 100,000 individuals per year in Western populationsCitation1, and the average prevalence of HD is approximately 10 in every 100,000 individualsCitation3–6. The prevalence of HD has increased worldwide between 10% and 20% each decade, likely due to increases in life expectancy and the advent of diagnostic testingCitation7,Citation8. In 2017, the incidence of HD among US Medicare beneficiaries ≥65 years of age was estimated at 6.1 per 100,000 person-years (females: 5.9 vs. males: 6.4) and the prevalence was estimated at 13.1 per 100,000 persons (females: 12.6 vs. males: 13.7)Citation9. HD is characterized by worsening cognitive, behavioral, and motor symptomsCitation2,Citation10, ultimately leading to progressive disability, loss of independence, and deathCitation11.

HD is descriptively categorized in early, middle/moderate, and late/advanced stages. As individuals with HD progress through these stages, functionality and independence decreases, with a higher need for assistance in all activities of daily living in those with later-stage diseaseCitation10.

There are currently no disease-modifying treatments available that can slow or reverse disease progressionCitation12, so the current goals of HD management are to relieve symptoms, maximize function, and optimize quality-of-lifeCitation13. The economic cost of HD increases with disease progression and is primarily driven by the cost of patient careCitation14,Citation15, meaning that HD places a substantial burden on healthcare systems and HD-affected individuals and families, through high healthcare resource utilization (HRU) and costs.

There is a need to understand how disease burden translates to direct healthcare costs and how resource use is associated with HD stage, particularly from a payer perspective. Though there is a paucity of data on these topics, previous analyses have established that a substantial cost burden is imposed by HDCitation14–19, although there were some limitations in these studies; individuals were only classified into a single stageCitation14, and the limited sample size reduced the generalizability of findingsCitation17.

Providing more comprehensive and up-to-date healthcare costs and HRU data for individuals with HD is vital to understanding unmet treatment needs, maximizing limited resources and ensuring that the greatest number of people can be managed effectively. Our aim in this study was to describe the HRU and direct economic cost burden by stage among individuals with HD in a US population.

Methods

Study design and data source

This was a retrospective cohort study using administrative claims data from the IBM MarketScan Commercial, Medicare Supplemental, and Multi-State Medicaid Databases from 1 January 2009 to 31 December 2018 (study period). These databases contain fully integrated, de-identified, patient-level healthcare claims data, including data from employees and their dependents from over 100 employer-sponsored and private health plans throughout the US.

The IBM MarketScan Commercial Database contains annualized data from several million individuals (encompassing employees, their spouses, and dependents) covered either by employer-sponsored fee-for-service or fully/partially capitated health plans. Medical claims are either linked to person-level enrollment information or outpatient prescription drug claims. The IBM MarketScan Medicare Supplemental Database includes the Medicare-covered portion of payment (represented by Coordination of Benefits amount), the employer-paid portion, and out-of-pocket patient expenses. It provides detailed cost, use, and outcomes data for healthcare services performed in both inpatient and outpatient settings. The IBM MarketScan Multi-State Medicaid Database contains data from over 47 million Medicaid enrollees, encompassing medical, surgical, and prescription drug dataCitation20.

Study population

Individuals aged ≥18 years with an HD claim, i.e. at least one medical claim with a diagnosis of HD (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] diagnosis code of 333.4 [Huntington’s chorea] or ICD-10-CM diagnosis code of G10 [Huntington’s disease]) between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2017 (identification period) were included in this study. Due to the nature of administrative claims data, molecular confirmation of cytosine-adenine-guanine repeat expansions was not available for the study participants.

Enrollment

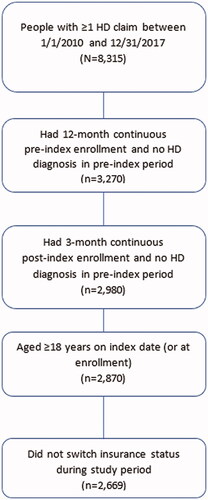

The index date was defined as the first date of HD diagnosis in the identification period. Individuals were required to have at least 12 months of continuous enrollment pre-index (baseline period), and at least 3 months of continuous enrollment post-index. A time period of 12 months of continuous enrollment pre-index was used to assess baseline HD staging. Individuals were followed until the end of continuous enrollment or end of data availability, whichever occurred first (); individuals were excluded if they switched insurance plans during the study period.

Key variables of interest

HD staging

In the absence of HD-related clinical measures (e.g. Total Functional Capacity [TFC] scale staging) in IBM MarketScan administrative claims databases, a proxy staging approach was required for this analysis. People with HD were categorized at baseline into early-, middle-, and late-stage disease by modifying a previously published algorithm with a hierarchical assessment of markers of disease severityCitation14. Divino et al.Citation14 developed and validated these disease markers based on a review of the clinical literature, an exploratory analysis of the data, and clinical input from experts. Late-stage disease markers were: use of nursing home care, use of a feeding tube, incontinence, bedsores, use of hospice care, evidence of two or more falls within 1 month, and swallowing problems. Middle-stage disease markers were: use of home assistance, physical therapy, dementia, gait disorder, dysarthria, speech therapy, or evidence of any falls. Individuals with late-stage disease were identified first based on the presence of any late-stage disease markers, followed by people with middle-stage disease based on the presence of middle-stage disease markers. Individuals without any late- or middle-stage disease markers were categorized as having early-stage disease.

Individuals with HD in the study were allowed to progress through disease stages after the index date; these events were known as staging episodes, and each staging episode started on the day of the evidence of a new marker in the claims data. The indexed stage was carried forward into the follow-up period until the next stage was observed. Therefore, people could contribute data to multiple stages throughout their follow-up. For these individuals, follow-up time was characterized by the amount of time they were in each stage before transitioning. Those who began in late stage remained in that disease stage for the remainder of the follow-up period.

All-cause HRU and costs

The following all-cause HRU and costs post-index were assessed for individuals with HD:

All-cause HRU (post-index)

Outpatient visits (included all non-inpatient-related visits).

Inpatient visits (included hospitalizations and other inpatient visits).

Emergency room (ER) visits (not resulting in hospitalization).

Pharmacy claims (any claims billed in the pharmacy setting).

HD-related pharmacy claims (full list of HD-related medications in Supplementary Table S1).

Radiology visits (magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography and positron emission tomography scans).

Physical and occupational therapy (PT/OT) visits.

All-cause costs (post-index)

Outpatient costs (all non-inpatient costs, including ER, radiology, PT/OT, and other outpatient services).

Inpatient visit costs (including hospitalizations and other inpatient visits).

Pharmacy costs.

HD-related pharmacy costs.

Long-term care/nursing home costs.

Skilled nursing facility (SNF) costs.

HRU (counts, proportions, mean, standard deviation [SD], median) and costs (mean, [SD], median), which were adjusted to 2018 US dollars (USD) using the medical component of the consumer price index, were reported descriptively for the overall HD cohort and by stageCitation21. Proportions of HRU were assessed in the 6-months post-index (among those with 6 months of follow-up) by baseline disease stage. HRU counts and costs were assessed per patient per month (PPPM) accounting for variable follow-up in the cohort and the time spent in each disease stage. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare HRU proportions in early-, middle-, and late-stage HD, and HRU counts and costs PPPM by stage were compared using the non-parametric Friedman test. This test was selected due to comparison of three or more groups of non-normal data with non-independent samples. SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all analyses.

Results

A total of 2,669 individuals with HD were included in this analysis (), 92.1% of whom had commercial and Medicare Supplemental insurance. The majority of individuals with HD were female (56.1%) and the mean (SD) age was 54.6 (16.6) years. The mean (SD) Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) score of individuals in the HD cohort was 1.2 (2), and mean follow-up was 27.1 months ().

Table 1. Participant characteristics by HD stage at baseline.

Of the total 2,669 individuals with HD, 1,432 (53.7%) had early-, 689 (25.8%) had middle-, and 548 (20.5%) had late-stage HD at baseline. Each group consisted of 52.6%, 59.4%, and 61.1% females, and the average follow-up time was 28.6, 26.7, and 23.8 months, respectively (). Among individuals with late-stage disease, 43.1% and 42.3% had Medicare supplemental and commercial insurance, respectively, while the majority of individuals with early- or middle-stage HD had commercial insurance (74.0% and 60.5%, respectively). The mean age increased in each disease stage cohort; 14.3%, 24.5%, and 43.6% were older than 65 years of age in the early-, middle-, and late-stage groups, respectively. Similarly, the mean CCI score increased in each disease stage cohort, with 5.7% of individuals in early-stage disease and 39.2% of those in late-stage disease with a CCI score of ≥3. At the end of follow-up, there were a total of 1,190 individuals in late-stage disease.

All-cause HRU

Nearly all individuals with HD had an outpatient visit (99.6%), irrespective of HD stage, while the majority of individuals had a pharmacy claim (88.8%) including HD-related pharmacy claims (62.9%) in the 6-months post-index. When comparing by HD stage, the proportion of inpatient visits, ER visits, and radiology procedures significantly increased with the disease stage (p <0.0001 for all comparisons), while more individuals in middle-stage HD had a pharmacy claim (p <0.0001) ().

Table 2. Any all-cause HRU within 6-months post-index by baseline HD stage.

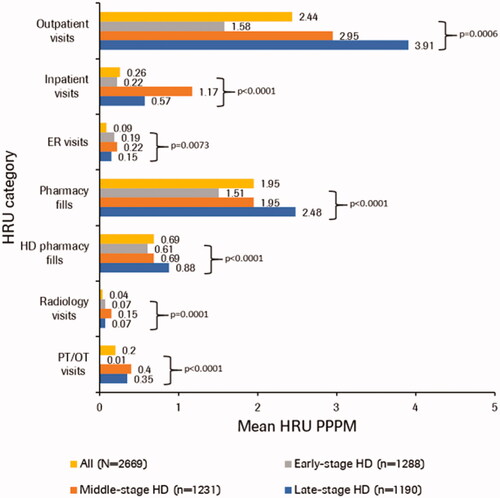

When comparing HRU PPPM by post-index HD stage, mean number of outpatient visits and pharmacy claims including HD-related pharmacy claims significantly increased with disease stage (p <0.05 for all comparisons), whereas mean number of inpatient visits and ER visits were highest in individuals with middle-stage HD (p <0.05 for all comparisons; and Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 2. Mean all-cause HRU PPPM by post-index HD stage. The non-parametric Friedman test was used for comparing the three HD stages. Individuals can contribute person-time and HRU to each category based on stages in follow-up. Outpatient visits, inpatient visits, ER visits, and pharmacy visits are mutually exclusive. HD-related pharmacy claims are a subset of pharmacy claims. Radiology and PT/OT procedures are subsets of inpatient and outpatient visits. ER, emergency room; HD, Huntington’s disease; HRU, healthcare resource utilization; PPPM, per patient per month; PT, physical therapy; OT, occupational therapy.

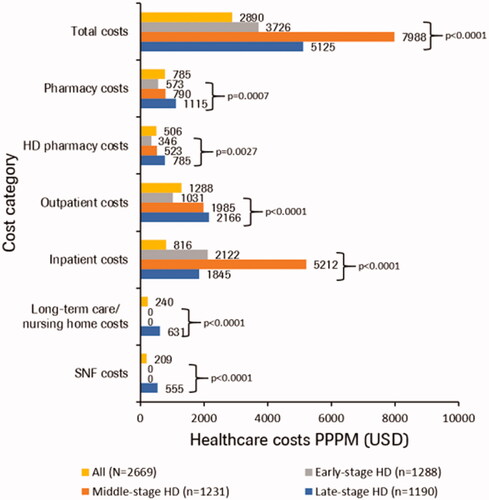

All-cause healthcare costs

Total median healthcare costs in HD PPPM increased with post-index disease stage, while mean total all-cause healthcare costs were $3,726, $7,988, and $5,125 in early-, middle-, and late-stage HD, respectively. Mean PPPM all-cause outpatient costs and pharmacy costs including HD-related pharmacy costs increased with disease stage, while inpatient costs were greatest in individuals with middle-stage disease (p < 0.01 for all comparisons). Costs related to long-term care/nursing home and SNF care were only observed in individuals with late-stage disease ( and Supplementary Table S3).

Figure 3. Mean all-cause healthcare costs PPPM (2018 USD) by post-index HD stage. Individuals can contribute person-time and HRU to each category based on stages in follow-up. Outpatient costs, inpatient costs, and pharmacy costs are mutually exclusive. HD-related pharmacy claims are a subset of pharmacy costs. Long-term care/nursing and skilled nursing facility are subsets of inpatient and outpatient costs. HD, Huntington’s disease; PPPM, per patient per month; SNF, skilled nursing facility.

Discussion

This retrospective US administrative claims study evaluated HRU and direct economic cost burden by stage among individuals with HD enrolled in commercial, Medicare Supplemental, and Medicaid insurance plans. Consistent with previous literatureCitation14,Citation15,Citation19, our results suggest that HD imposes a significant cost burden on affected individuals and families as well as the healthcare system, which worsens with disease stage. The substantial HRU among people with HD indicates a high unmet medical need in this population.

Our study highlighted differences in individuals’ characteristics by HD stage. For example, most individuals with early- or middle-stage HD were commercially insured enrollees (61–74%), compared with only 11–14% of Medicaid beneficiaries and 15–26% of Medicare beneficiaries. One previous analysis reported that, while individuals with commercial insurance were evenly distributed by HD stage in the study, most Medicaid beneficiaries with HD (74%) were classified as late stageCitation14. These findings may be reflective of the transition of people with HD from commercial insurance to Medicaid due to loss of employmentCitation19, or those diagnosed during mid-life (30–50 years) and progressed into late-stage disease at the time of Medicare eligibility. Furthermore, over 40% of individuals with late-stage HD were aged 65 years or older. We also found that 5.7% of individuals with early-stage disease had a CCI score of ≥3, whereas 39.2% of individuals with late-stage disease had a CCI score of ≥3, suggesting a high comorbidity burden in individuals with late-stage disease. Similar observations have been reported for both psychiatric and physical comorbidities, which were higher in those with middle- and late-stage disease compared with early HDCitation14,Citation19. The higher comorbidity burden in individuals with middle- and late-stage HD may further contribute to the increased disease burden relative to individuals with early-stage HD.

We found that the mean number of outpatient visits and pharmacy claims significantly increased with disease stage, while the mean number of inpatient admissions was highest in middle-stage HD. These results suggest that individuals with middle- and late-stage HD have substantial healthcare services utilization, indicating a need for greater disease management and care. These findings are corroborated by previous research, which has shown that individuals with middle-stage HD often require physical and/or speech therapy, or home assistance, whilst those with late-stage disease may additionally require more intensive care, such as nursing home care and feeding tube useCitation14,Citation19. This is expected given that HD causes significant progressive motor, cognitive, and psychiatric impairment, reducing an individual’s independence and the ability to perform activities of daily living.

The mean total all-cause healthcare costs for individuals with HD was $2,890 PPPM, where outpatient visits accounted for 45% of the total costs. Mean outpatient costs and pharmacy costs, including HD-related pharmacy costs, significantly increased with disease stage. We found that total median costs increased with HD stage while mean total costs were higher for middle-stage HD. Our overall cost findings are similar to those of Divino et al.Citation14, which showed that mean (SD) total annualized cost per patient increased by stage (commercial: $4,947 [$6,040] to $22,582 [$39,028]; Medicaid: $3,257 [$5,670] to $37,495 [$27,111]), and that outpatient costs were the primary healthcare cost component; however, our mean total costs PPPM estimates were higher. This can be attributed to differences in study period and methods.

Interestingly, the mean total healthcare costs in our study were highest in individuals with middle-stage disease, primarily driven by high mean inpatient visit costs compared with those with early- and late-stage disease. The reasons for increased mean inpatient costs and visits in individuals with middle-stage disease in our study are unclear. However, one explanation could be that progressive motor dysfunction observed in individuals with middle-stage disease results in an increased risk of falls causing injury, thereby resulting in more inpatient visits. Risk of falls may be reduced in late-stage disease as these individuals are more likely to be using wheelchairs or walking aids or be bed boundCitation2. Another potential explanation may be shifting of care from the acute inpatient setting to nursing home care in late-stage diseaseCitation18. In fact, mean costs associated with long-term, nursing home, or SNF care were only observed in our late-stage HD cohort. Also, increased mean healthcare costs in individuals with middle-stage disease could be due to data outliers as seen by the large SDs observed in the mean total costs and mean inpatient costs in the middle-stage HD cohort. Total median costs increased incrementally by stage, highlighting the large variation in HRU and costs data in this study. Of note, mean outpatient use and costs significantly increased at each stage for individuals with HD, deviating from the trend seen for inpatient services. It is therefore important to emphasize that, whilst inpatient use was greater in middle-stage disease, outpatient use still increases with disease stage. Regardless, our results suggest that early intervention in these individuals may help to delay disease progression, which in turn may lower the HRU and cost burden associated with middle- and late-stage HD.

We compared the mean total all-cause healthcare costs for individuals with HD in our study ($2,890 PPPM or ∼$34,680 per patient in 2018 USD) with those previously reported for other neurodegenerative diseases in commercially insured populations. Our cost estimates in HD were higher than those reported for Multiple Sclerosis and similar to those reported for Parkinson’s disease, but lower than those reported for Alzheimer’s disease in the literatureCitation22–25. In 2010, Asche et al.Citation22, using commercial insurance claims from 2004–2006, reported that patients with Multiple Sclerosis were estimated to have an annual all-cause cost of $18,829 (adjusted to 2010 USD); this would be equivalent to $21,539 in 2018 USDCitation25. Huse et al.Citation23, in 2005, using commercial insurance claims from 1999–2002, estimated an annual direct medical cost of $23,101 in 2002 USD (∼$32,332 in 2018 USD) in patients with Parkinson’s diseaseCitation25, while in 2007 Joyce et al.Citation24, using commercial insurance claims from 1999–2003, estimated an annual mean total cost of $28,263 in 2003 USD (∼$38,555 in 2018 USD) in patients with Alzheimer’s disease, which is higher than the estimated cost for HD in our study.

Our study provides a comprehensive update on the burden of HD in a US population. Whilst we initially identified 8,315 individuals with ≥1 claim in the study period, our eligibility criteria necessitated removing those individuals that were not ≥18 years old at the index date, did not have 12 months continuous pre-index enrollment, or 3 months post-index enrollment, or those with an HD diagnosis in the pre-index period (). Still, this is, to our knowledge, the largest real-world analysis of the burden of illness among people with HD in the US to date. Furthermore, our study also addresses some limitations observed in previous studies. For instance, in previous studies, costs of HD progression based on a single stage at baseline were examined; in our study, people could transition between HD stages, which potentially allowed for a more accurate characterization of HRU and costs attributable to each stage of the disease. Additionally, our study covers a large, geographically diverse HD population across different insured populations. However, several limitations of this analysis should be noted. First, our study aimed at estimating HRU and costs by disease stage by assessing the feasibility of using disease markers from a previously developed, validated, and published claims-based algorithmCitation14 as a means of estimating disease stage. Clinical assessment of disease progression using the TFC scale is based on the patient’s functioning across five areas, including activities of daily living, domestic chores, and level of careCitation26. The patient’s ability and independence in these various areas of the TFC scale decline as they progress through HD stages, which provides the underlying concept for the claims-based algorithm utilized in our study. The disease markers in the algorithm are used as a proxy to indicate decline in the patient’s functional status as a means of identifying the stage of the disease. However, this approach could have resulted in potential misclassification of disease stage and thereby HRU and costs by stage. Secondly, the majority of individuals in our data set were members of commercial insurance plans, with a smaller number representing Medicare and Medicaid data. This may confound our findings, especially when comparing them with other analyses that exclusively utilized Medicare dataCitation9. Additionally, our findings may not be generalizable to individuals with other types of insurance outside of commercial, Medicare Supplemental, or Medicaid insurance, or uninsured individuals in the US. Furthermore, there is a lack of visibility into the full long-term care/nursing home-related costs for commercially enrolled individuals in this analysis, as these costs are not typically covered by commercial insurance plans. Also, Medicare does not cover costs of SNF care beyond 100 days. Therefore, healthcare costs, particularly among individuals with late-stage HD who utilized long-term care or nursing home care, may potentially be underestimated in our study. Also, we did not evaluate the indirect costs of HD (e.g. presenteeism/absenteeism, caregiver costs), which may be substantial as HD typically affects people at the peak of their earning potential (between 30 and 50 years old), and has been shown to interfere with an individual's ability to function at work. Moreover, individuals with HD who are not working may not be captured by MarketScan because the data include employer-sponsored health plans, though it may capture individuals who are dependents covered under their working spouses. Another limitation inherent in retrospective claims analyses is the possibility of coding errors and misclassification, which could affect the validity of our findings. Additionally, mean follow-up for all individuals with HD was approximately 2 years, which may not adequately capture the full burden of HD due to the slowly progressive nature and long natural history of the disease. Also, our analysis relied on ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes for HD, thus limiting it to symptomatic or manifest individuals; molecular confirmation data for participants were unavailable in this claims data analysis. Finally, staging was based partly on HRU-related markers; therefore, an observed increase in costs by stage could, to some degree, be due to the construction of the disease stage measure. This approach has been used in previous literatureCitation14,Citation19,Citation27,Citation28 in the absence of clinical measures (e.g. TFC in HD) in claims data and, whilst it has not yet been validated against TFC, it is a suitable proxy. However, this approach could potentially have resulted in some misclassification by disease stage.

Overall, our study supports and extends previous research showing that HRU and costs of care in HD increase with disease stage. The greater healthcare burden among individuals with middle- and late-stage disease compared with those with early-stage disease underlines the complexity of HD, as well as the need for better care and access to interventions that can slow or prevent disease progression. And whilst previous comparisons of HRU and costs in HD have demonstrated the high economic burden that HD places on healthcare systems and individuals with HD compared with those without HDCitation29, further research is required to fully understand the incremental burden imposed by HD across disease stages.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Genentech Inc.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

TMT: stock options with Genentech. AE: stock options with Roche/Genentech. IMA: stock options with Genentech. JTT: stock options with Roche. AMP: stock options with Roche/Genentech. AE: employment with Roche/Genentech. TMT: employment with Genentech. IMA: employment with Genentech. JTT: employment with Genentech. AMP: employment with Roche/Genentech. AS: employment with Genesis Research (which receives consulting fees from Genentech/Roche). RLMF: employment with CHDI Management/CHDI Foundation. JL: employment with CHDI Management/CHDI Foundation.

A reviewer on this manuscript has disclosed that they provide educational consultancy for PTC, paid to institution, not HD. They are also on the Novartis advisory board, and received MEGS awards from Sanofi, Akcea, and AMGEN for activities not related to this topic. Their center has received reimbursement for clinical trials from Roche and Prilenia, and research grant funding from the Scottish Government, University of Aberdeen development trust, MRC, and HTA. They have also attended meetings sponsored by Akcea, MSD, AMGEN, Sanofi, Novartis, Teva, and Daiichi Sankyo. The other peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

The Deputy Editor in Chief helped with adjudicating the final decision on this paper.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (53.8 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank Greg Rowe of Chrysalis Medical Communications for providing medical writing support, which was funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (http://www.ismpp.org/gpp3).

References

- Bates GP, Dorsey R, Gusella JF, et al. Huntington disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:722.

- Roos RA. Huntington’s disease: a clinical review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5(5):40.

- Evans SJW, Douglas I, Rawlins MD, et al. Prevalence of adult Huntington’s disease in the UK based on diagnoses recorded in general practice records. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84(10):1156–1160.

- Squitieri F, Griguoli A, Capelli G, et al. Epidemiology of Huntington disease: first post-HTT gene analysis of prevalence in Italy. Clin Genet. 2016;89(3):367–370.

- Fisher ER, Hayden MR. Multisource ascertainment of Huntington disease in Canada: prevalence and population at risk. Mov Disord. 2014;29(1):105–114.

- Rawlins M. Huntington’s disease out of the closet? Lancet. 2010;376(9750):1372–1373.

- Rawlins MD, Wexler NS, Wexler AR, et al. The prevalence of Huntington’s disease. Neuroepidemiology. 2016;46(2):144–153.

- Wexler NS, Collett L, Wexler AR, et al. Incidence of adult Huntington’s disease in the UK: a UK-based primary care study and a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2016;6(2):e009070.

- Exuzides A, et al. Epidemiology of Huntington’s Disease (HD) in the US medicare population (670). Neurology. 2020;94(15 Supplement):670.

- Ross CA, Aylward EH, Wild EJ, et al. Huntington disease: natural history, biomarkers and prospects for therapeutics. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10(4):204–216.

- Keum JW, Shin A, Gillis T, et al. The HTT CAG-expansion mutation determines age at death but not disease duration in Huntington disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;98(2):287–298.

- Wild EJ, Tabrizi SJ. Therapies targeting DNA and RNA in Huntington’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(10):837–847.

- Simpson SA, Rae D. A standard of care for Huntington’s disease: who, what and why. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2012;2(1):1–5.

- Divino V, Dekoven M, Warner JH, et al. The direct medical costs of Huntington’s disease by stage. A retrospective commercial and Medicaid claims data analysis. J Med Econ. 2013;16(8):1043–1050.

- Jones C, Busse M, Quinn L, et al. The societal cost of Huntington’s disease: are we underestimating the burden? Eur J Neurol. 2016;23(10):1588–1590.

- Murman DL, Chen Q, Colucci PM, et al. Comparison of healthcare utilization and direct costs in three degenerative dementias. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10(3):328–336.

- McCabe MP, O’Connor EJ. A longitudinal study of economic pressure among people living with a progressive neurological illness. Chronic Illn. 2009;5(3):177–183.

- Dubinsky RM. No going home for hospitalized Huntington’s disease patients. Mov Disord. 2005;20(10):1316–1322.

- Anderson KE, Divino V, DeKoven M, et al. Interventional differences among Huntington’s disease patients by disease progression in commercial and medicaid populations. J Huntingtons Dis. 2014;3(4):355–363.

- IBM MarketScan Research Databases White Paper for Life Sciences Researchers. 2020. [cited 2021 May 07]. Available from: https://www.ibm.com/products/marketscan-research-databases/resources.

- Measuring Price Change in the CPI: Medical care. 2020. [cited cited 2021 May 07]. Available from: https://www.bls.gov/cpi/factsheets/medical-care.htm.

- Asche CV, Singer ME, Jhaveri M, et al. All-cause health care utilization and costs associated with newly diagnosed multiple sclerosis in the United States. JMCP. 2010;16(9):703–712.

- Huse DM, Schulman K, Orsini L, et al. Burden of illness in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2005;20(11):1449–1454.

- Joyce AT, Zhao Y, Bowman L, et al. Burden of illness among commercially insured patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dementia. 2007;3(3):204–210.

- Consumer Price Index Inflation Calculator. 2022. [cited 2022 Feb 15]. Available from: https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl

- Shoulson I, Fahn S. Huntington disease: clinical care and evaluation. Neurology. 1979;29(1):1–3.

- Winter Y, Balzer-Geldsetzer M, von Campenhausen S, et al. Trends in resource utilization for Parkinson’s disease in Germany. J Neurol Sci. 2010;294(1-2):18–22.

- Barer Y, Gavrielov N, Coloma P, et al. Huntington’s disease in Israel – 20 years of follow up from Maccabi healthcare services. Mov Disord. 2020;35(suppl 1). [cited 2022 May 23]. Available from: https://www.mdsabstracts.org/abstract/huntingtons-disease-in-israel-20-years-of-follow-up-from-maccabi-healthcare-services/

- Exuzides A, To TM, Abbass I, et al. Healthcare resource utilisation and costs among patients with versus without Huntington’s disease in the US population. Mov Disord. 2020;35(suppl 1). [cited 2022 May 23]. Available from: https://www.mdsabstracts.org/abstract/healthcare-resource-utilisation-and-costs-among-patients-with-versus-without-huntingtons-disease-in-the-us-population/